Rep:Mod:EllynIII

Ellyn Junker 00602040

Module 3 - Characterisation of Cycloaddition Transition States

The transition state of a reaction has maximal energy on a potential energy surface. Its geometry may not be calculated using the molecular mechanics and force field approach that is sufficient for molecules in their ground state as the calculations are not orientated around electron distribution and hence do not describe the breaking and formation of bonds. Therefore the Schrödinger equation will be used to calculate the potential energy surface of two cycloaddition reactions: the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels-Alder reaction. Hence the transition state may be located. Additional information on the kinetics of the reactions - such as activation barrier heights and the reaction path - may also be calculated.

Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-Hexadiene

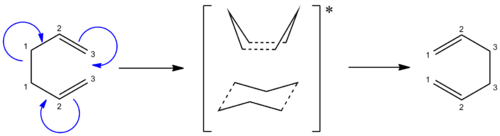

The Cope Rearrangement involves a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement. The reaction may go through a chair or a boat transition state conformation (figure 1) depending on the geometry of the reactant, both forms will be studied. 1,5-hexadiene is computationally the simplest molecule the Cope rearrangement may occur in - thus it will be used to observe the transition state of this extensively studied reaction.

Optimisation of 1,5-Hexadiene Ground State

Firstly the most thermodynamically stable conformation of 1,5-hexadiene was found. The molecule has 3 freely rotating C-C single bonds, thus the molecule may exists as several different conformers. In alkanes, a torsional angle of ±60° or 180° tends to be the lowest in energy as they minimise steric repulsion. These are the gauche and antiperiplanar conformation respectively. Therefore only torsional angles of these magnitudes will be considered in finding the lowest energy conformers. The molecule was drawn in GaussView with a dihedral angle of 180° between the central 4 carbons and it was optimised using the fairly basic Hartree-Fock method and 3-21G basis set (HF/3-21G) and the memory was specified as 250 MB. This was repeated for 3 other variations on the anti-periplanar geometry and also 6 gauche conformers. A comparison of their energies and point groups are shown in table 1.

| Conformer[.log file] | Total Energy / Hartrees | Relative Energy / kcal mol-1 | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1[1] | -231.69260 | 0.04 | C2 |

| Anti 2[2] | -231.69254 | 0.08 | Ci |

| Anti 3[3] | -231.68907 | 2.25 | C2h |

| Anti 4[4] | -231.69097 | 1.06 | C1 |

| Gauche 1[5] | -231.68772 | 3.10 | C2 |

| Gauche 2[6] | -231.69168 | 0.62 | C2 |

| Gauche 3[7] | -231.69266 | 0.00 | C1 |

| Gauche 4[8] | -231.69153 | 0.71 | C2 |

| Gauche 5[9] | -231.68962 | 1.91 | C1 |

| Gauche 6[10] | -231.68916 | 2.20 | C1 |

It can be seen from the table that the lowest energy conformers are by far Gauche 3, Anti 1 and Anti 2, with Gauche 3 being lowest. This result is surprising as it was expected that the antiperiplanar conformation would be lowest in energy.

These conformers were reoptimised using a higher level of accuracy with the hybrid method, B3LYP, which combines the Hartree-Fock and other exchange-correlation functions. The basis set used was 6-31G(d).

| Conformer[.log file] | Total Energy / Hartrees | Relative Energy / kcal mol-1 | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1[11] | -234.61180 | 0.00 | C2 |

| Anti 2[12] | -234.61170 | 0.05 | Ci |

| Gauche 3[13] | -234.61133 | 0.29 | C1 |

After reoptimisation, the Anti 1 conformer was now lowest in energy as expected with the Gauche 3 conformer being highest in energy. This difference arises from the steric clash between the -CHCH2 groups (figure 2). In addition, the dihedral angle between the central 4 carbons is 66.7° (whereas a perfect gauche conformer would have a dihedral angle of 60°) thus the overlap between the σC-H/σ*C-H, σC-H/σ*C-C and σC-C/σ*C-H orbitals is not as good compared to that in the anti forms where the dihedral angles are close to perfect anti-periplanar (178° and 180°).

Thermochemistry

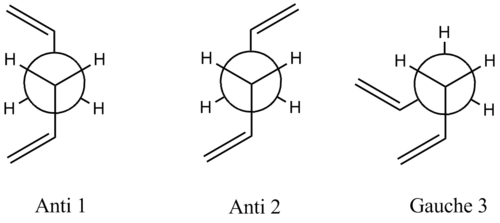

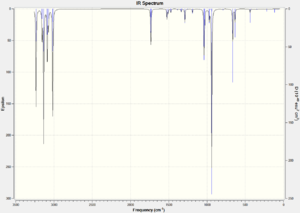

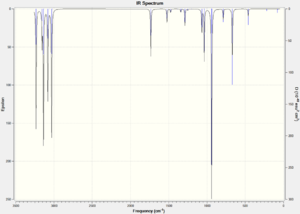

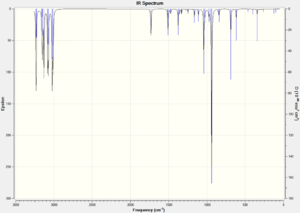

In order to gain information on the thermochemistry of the conformers the frequencies were calculated. The frequency calculations contain additional terms which correspond to the thermochemistry. The calculations were run under the B3LYP/6-31G(d) method and basis set. There were no negative vibrations, confirming that the geometries were minima on the potential energy surface. The vibrational spectra are shown in figure 3, they are extremely similar with some differences in the intensities of the symmetric C=C stretch at around 1730 cm-1 - the symmetric stretch in the Anti 2 conformation has an intensity of zero as it has a center of inversion hence the stretch causes no change in its overall dipole.

|

|

|

| Figure 3: Calculated IR spectra of the three most stable conformers of 1,5-hexadiene. | ||

The .log files provided the values for the following thermochemical properties:

- The sum of potential energy at 0 K plus the zero-point vibrational energy E = Eelec + ZPE

- Energy including translation, rotational and vibrational contributions (sum of the electronic and thermal energies) E = E + Etrans + Erot + Evib

- The additional correction to RT (sum of the electronic and thermal enthalpies) H = E + RT

- The entropic contribution to the free energy (sum of the electronic and thermal free energies)G = H - TS

These are displayed in table 3.

The frequency calculations were also run with the temperature specified at 0.0001 K (specifying 0 K would cause the calculations to fail).

| Conformer[.log file] | E = Eelec + ZPE | E = E + Etrans + Erot + Evib | H = E + RT | G = H - TS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti 1[14] | -234.46929 | -234.46197 | -234.46102 | -234.500162 |

| Anti 2[15] | -234.46921 | -234.46186 | -234.46091 | -234.50082 |

| Gauche 3[16] | -234.46869 | -234.46146 | -234.460520 | -234.50011 |

At 0 K the energies were the same for each property, this is because at absolute zero there is no thermal contribution - thus the only contributions come from the zero point energy. The energies (in units of Hartrees) at 0 K are listed below:

By increasing the temperature (from 0 to 298.15 K) the sum of the electronic and thermal free energies becomes more negative, this is expected as the Gibb's free energy is related to temperature by the equation G = H - TS. The thermal contributions to the entropy and energy is also increased - also resulting in a increase in energy as the temperature is increased.

The zero point energy is the same at 0 K as it is at 298.15 K, this is expected as temperature has no effect on the zero point energy which is defined as ½hν.

Optimisation of Transition State

Optimising the Chair

An allyl fragment CH2CHCH2 with C-C bond order of 1.5 was drawn in GaussView. It was optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory. This was used to form a guess of the chair transition state which was optimised by two different methods.

Computing the Force Constant

The transition state was optimised at the same time as calculating the frequencies by selecting the Opt + Freq option. It was optimised to a transition state by employing the Berny Algorithum and the HF/3-21G level of theory. The force constants were set to be calculated once and the keyword NoEigen was used to prevent the calculation from failing of more than one imaginary frequency were to be produced.

The resulting output[20] showed one negative frequency at -818 cm-1 which corresponds to the imaginary vibration related to the bond breaking and formation in the reaction (figure 4).

Freezing Reaction Coordinates

The second method for optimisation of the transition state was carried out by freezing the coordinates of the terminal carbon atoms by setting the distance between these as 2.2 Å at either end. The geometry was optimised to a minimum again using the HF/3-21G level of theory. This produced a structure with the interatomic distances frozen at 2.2 Å.

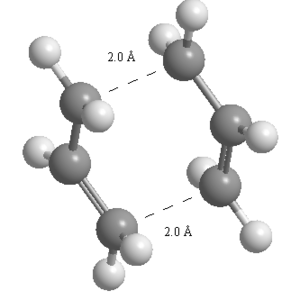

| |||

| Figure 5: Optimised chair transition state with frozen interatomic distances at 2.2 Å. |

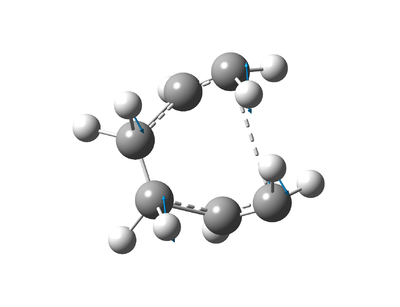

The structure was reoptimised as a transition state using the Berny Algorithm, this time not constraining the distances between the terminal carbons. This allowed the transition state to be found[21] (figure 6) with the bond forming/breaking lengths at 2.0199 Å (4 sf). This is very similar to the bond forming/breaking lengths from the force constant computed optimisation (2.0200 Å). The C-C distances indicate that the transition state found is the low energy aromatic transition state, opposed to the biradicaloid transition state[22].

|

| Figure 6: Optimised chair transition state. |

Optimising the Boat

In order to optimise the boat transition state an alternative method was used, QST2 (Quadratic Synchronised Transit). Unlike the previous methods used where the transition state structure was guessed, the reactant and product geometries are specified and the transition state is found by interpolating between the two structures to find the quadratic region of the potential energy surface. Other methods may then be applied to find the saddle point where the transition state lies.

The B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimised structure of the Anti 2 conformer was used to define the reactant and product. The atom numbers were defined so that a bond was formed between atom 1 and 6 and a bond broken between 3 and 4 in the product. The structures were optimised to a transition state using the QST2 method, however the calculations failed as the reactant and product are poorly specified due to the many degrees of rotation about the central C-C single bonds - thus there is no obvious reaction path between the two.

The geometries of the reactant and product were adjusted so that the dihedral angle between the central 4 atoms was zero and the bond angles of the central carbons were set to 100°. The structures were optimised again using the QST2 method and HF/3-21G level of theory. The resulting output[23] (visualise) gave the transition state structure which also had an imaginary frequency at -840 cm-1 representative of the bond breaking and forming action of the reaction (figure 7).

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate

The intrinsic reaction coordinate is the minimum energy pathway between the reactant and product which goes via the transition state[24]. This minimises the transition state to a minimum, therefore due to the endothermic nature of the reaction the conformation of the product may be found, if the reaction is in accordance with Hammond's Postulate.

IRC of the Chair Transition State

The IRC was calculated for the HF/3-21G optimised structure of the chair transition state for the forward direction only as the structure of the reactant is the same as the product - thus the reaction coordinate will be symmetrical. The maximum number of steps was set to 50.

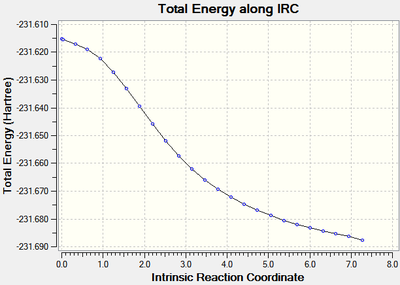

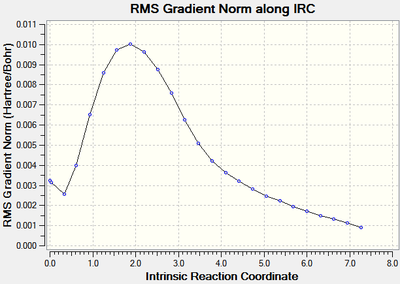

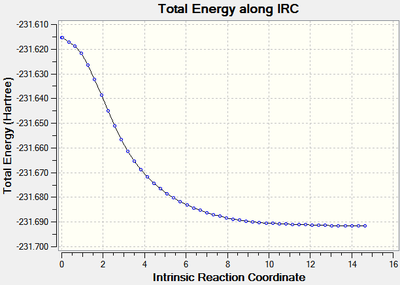

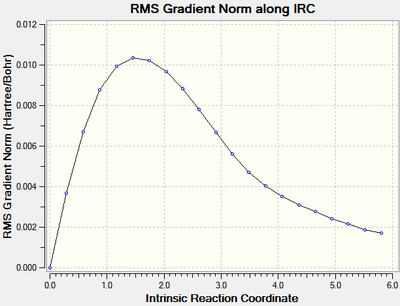

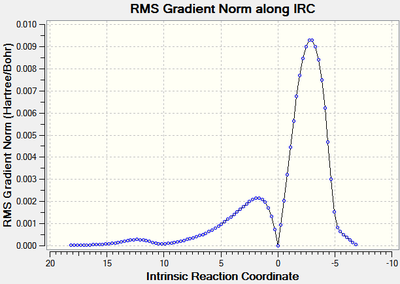

The calculations stopped after 24 steps, however it can be seen that the root mean square of the gradient did not approach close enough to zero (figure 8) indicating that the optimisation did not run to completion as the requirement that dy/dx=0 had not be fulfilled. The energy of the optimised geometry was -231.68770 Hartrees.

|

|

| Figure 8: The energy and RMS of the IRC[25] of the chair transition state. | |

The structure therefore needed to be further optimised to find the minimum energy, this was approached in three different ways.

1) Optimisation of the last point of the IRC

The last point of the IRC was optimised to a minimum at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The optimised geometry[26] is representative of the Gauche 2 conformer, this is confirmed by the fact that it has the same energy as the structure calculated in the first section (-231.69168 Hartrees). Unfortunately, by using this method, if the geometry at the last step of the IRC is not close to the product, the optimisation will of course be inaccurate.

2) IRC with a higher maximum number of steps

The maximum number of steps was increased to 250, however the calculation still stopped after 24 steps[27], giving a geometry with the same energy as previously calculated. Thus this method is only useful if the calculation runs for the full number of specified steps and the root mean square is not at a minimum, therefore indicating more steps are required.

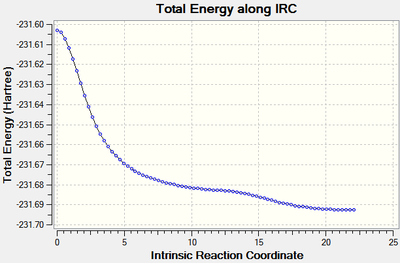

3) IRC with force constants calculated at each step

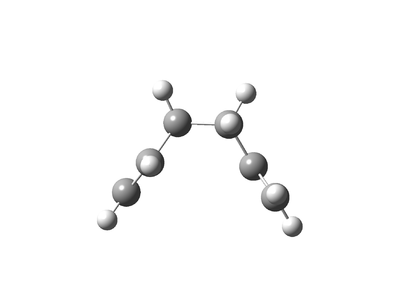

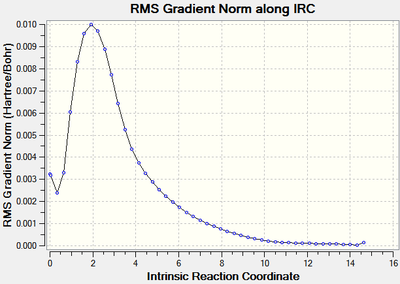

The set up was adjusted so that the force constants were calculated at each step, the root mean square of the gradient at the last step was close to zero (2.1 x 10-5 Hartree/Bohr), indicating that the minimum energy had been found which was 10.37 kJ mol-1 lower in energy than the previously calculated energy with IRC (-231.69165700 Hartrees for the last point of the IRC). There was also no negative frequencies for the last point of the IRC also indicating that a global minimum had been found. The last point of the IRC was then optimised to a minimum[28] using the HF/3-21G level of theory and gave the structure in figure 10 with an energy of -231.69166702 Hartrees.

|

|

| Figure 11: The energy and RMS of the IRC[29] where all force constants were calculated of the chair transition state. | |

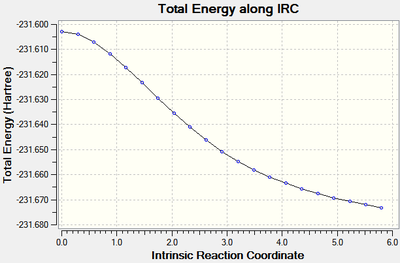

IRC of the Boat Transition State

The same process was repeated for the boat transition state. The calculation[30] stopped after 20 steps, again the minimum energy had not been found indicated by the root mean square graph (figure 10), the last point had an energy of -231.67316 Hartrees.

|

|

| Figure 13: The energy and RMS of the IRC of the boat transition state. | |

As the minimum energy had not been found, steps 1 and 2 used above were not repeated for the boat transition state, yet the IRC was calculated again with force constants being calculated at each step, a maximum of 100 steps was specified.

The calculation[31] stopped after 76 steps, the RMS of the gradient of the reaction coordinate was very close to zero (1.1 x 10-5 Hartree/Bohr) indicating a minimum had been found (figure 11). The last point of the the IRC which is representative of the product had an energy of -231.69265935 Hartrees. This was again optimised to a minimum using the HF/3-21G level of theory and had an energy of -231.69266117 Hartrees which is actually lower than the energy of the product of the rearrangement via the chair transition state by 2.61 kJ mol-1.

|

|

| Figure 14: The energy and RMS of the IRC of the boat transition state with all force constants calculated. | |

Reaction Activation Energies

The activation energy of a reaction may be specified as the energy difference between the transition state and the reactant (or in this case the product too as they have the same geometries). The geometry of the product (obtained from the previous section) and the transition state were optimised for both the chair and the boat using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory. These energies were compared with those obtained from the HF/3-21G optimisation.

| Transition State | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-21G(d) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State Energy[.log file] / Hartrees | Product Energy[.log file] / Hartrees | Activation Energy / Hartrees | Activation Energy / kJ mol-1 | Transition State Energy[.log file] / Hartrees | Product Energy[.log file] / Hartrees | Activation Energy / Hartrees | Activation Energy / kJ mol-1 | |

| Chair | -231.61932199[32] | -231.69166702[33] | 0.07234503 | 189.9 | -234.55698449[34] | -234.61068823[35] | 0.05370374 | 141.0 |

| Boat | -231.60280248[36] | -231.69266117[37] | 0.08985869 | 235.9 | -234.54309274[38] | -234.61132926[39] | 0.06823652 | 179.2 |

It can be seen from the data that the reaction via the boat transition state has a higher activation energy than the reaction via the chair. This is to be expected due to the unfavourable diaxial repulsions of the hydrogens in the boat transition state. This indicates that the reaction via the chair transition state is kinetically favoured.

Conclusions

The chair and boat transition states of the Cope rearrangement were successfully optimised to a minimum, they were then used to calculate the reaction coordinate and determine the geometry of the product and reactant. It was found that that the reaction via the chair transition state had a lower activation energy, thus it is expected that this would be the predominant pathway.

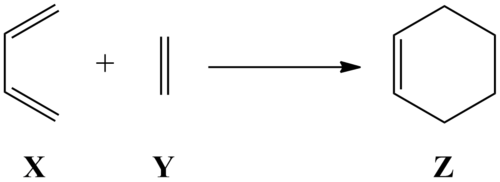

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels-Alder cycloaddition is a concerted pericyclic reaction between a conjugated diene and a dienophile. The diene is an electron-rich species therefore it has a high energy HOMO, the dienophile tends to be functionalised with electron withdrawing groups, increasing its electron-deficiency and lowering the energy of its LUMO - therefore encouraging a faster reaction due to the smaller difference in orbital energies between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile.

The computationally simplest of Diels-Alder cycloadditions is the reaction of cis-butadiene X with ethene Y, therefore this reaction will be used to computationally investigate the geometry of the transition state and the reaction's kinetic data.

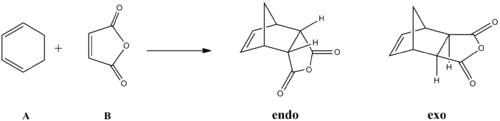

There are two possible products of the Diels-Alder reaction - exo and endo. Therefore the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene A with maleic anhydride B will also be investigated to determine the molecular orbital consequences on the regioselectivity of the reaction.

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition of cis-butadiene and ethene

For a reaction to proceed, the symmetry of the HOMO of X must be the same LUMO of Y. This results in good orbital overlap and a potentially successful reaction. Therefore the symmetries of the HOMO and LUMO of both X and Y will be investigated and the subsequent consequences on the structure of the transition state and the kinetic properties.

Optimisation of the Reactants

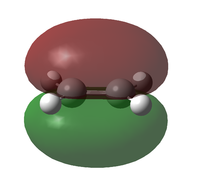

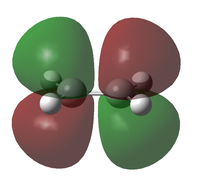

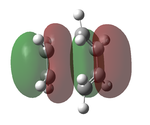

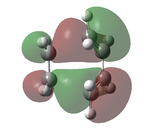

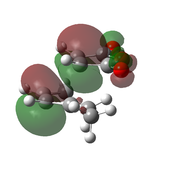

The two reactants, cis-butadiene and ethene, were optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method, and then further optimised using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory. Their HOMO and LUMO's were visualised using GaussView. Both reactants have a σv plane of symmetry and the orbitals have been labelled symmetric and asymmetric with respect to this plane.

| Molecule | HOMO | LUMO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene Y | MO |  |

|

| Symmetry | s | a | |

| Energy (AM1)[40] / eV | -0.38778 | +0.05285 | |

| Energy (B3LYP/6-321G(d))[41] / eV | -0.26667 | +0.01881 | |

| cis-butadiene X | MO |  |

|

| Symmetry | a | s | |

| Energy (AM1)[42] / eV | -0.34381 | +0.01707 | |

| Energy (B3LYP/6-321G(d))[43] / eV | -0.22735 | -0.03012 | |

It can be seen from the pictorial representations of the HOMOs and LUMOs that the HOMO of X has the same symmetry as the LUMO of Y, thus a reaction would be possible. This is also true for the LUMO of X and the HOMO of Y, however for a reaction to be successful, the reactants must also have a small difference in energy between the reacting orbitals. The difference in energy between the HOMO of X and LUMO of Y is 0.20854 eV (calculated at the B3LYP/6-21G(d) level of theory), yet the difference between the LUMO of X and HOMO of Y is 0.29679 eV, thus indicating that a reaction between the HOMO of X and LUMO of Y is more likely.

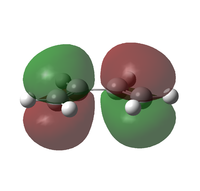

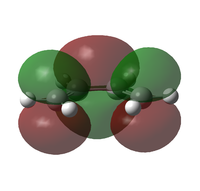

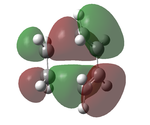

Optimisation of the Transition State

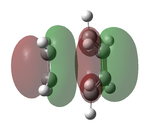

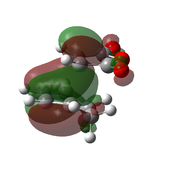

The transition state was optimised using the freeze coordinate method used for the Cope-Rearrangement. The optimised structure of X and Y were used to form a 'guess' transition state, the coordinates were frozen with an inter atomic distance of 2.2 Å between the termini and the structure was optimised to a minimum using the AM1 level of theory. This structure was then optimised to a transition state using the Berny algorithm. The structure had a negative frequency representative of the bond making/breaking action. Its LUMO, HOMO and HOMO-1 was visualised using GuassView. This process was also repeated at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory.

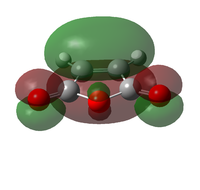

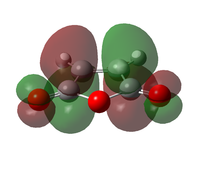

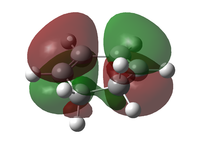

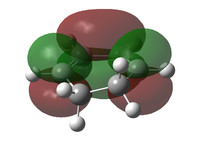

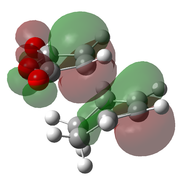

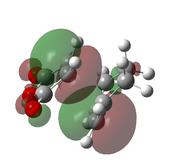

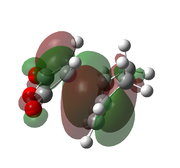

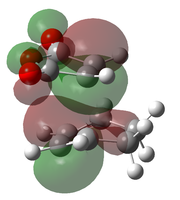

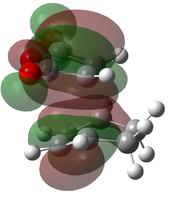

| Method | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | Energy / Hartrees | Negative Vibration / cm-1 | Pictorial Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1[44] |  |

|

|

0.11165 | -956 |  |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d)[45] |  |

|

|

-234.5439 | -525 |  |

The imaginary vibrations calculated by the two different methods are very different, this is due to the different parameters the methods use. The HOMO and HOMO-1 are switched in terms of relative energy when the method is changed. It appears that the HOMO calculated by the AM1 method was formed by the HOMO of X and LUMO of Y as it corresponds to their symmetries and the LUMO of the transition state was formed upon the overlap of the LUMO of X and HOMO of Y.

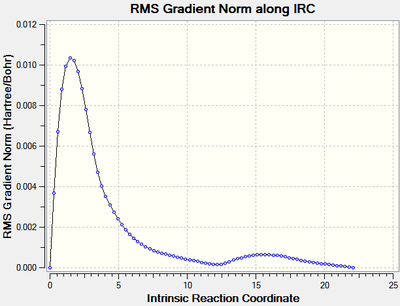

IRC Analysis

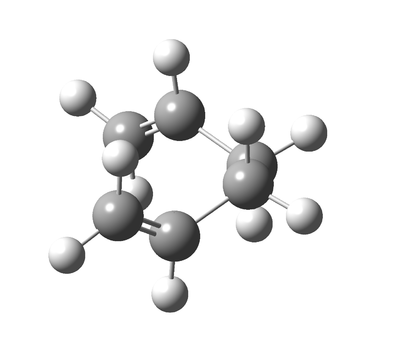

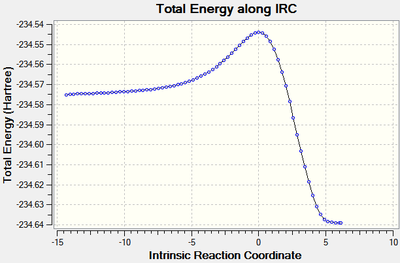

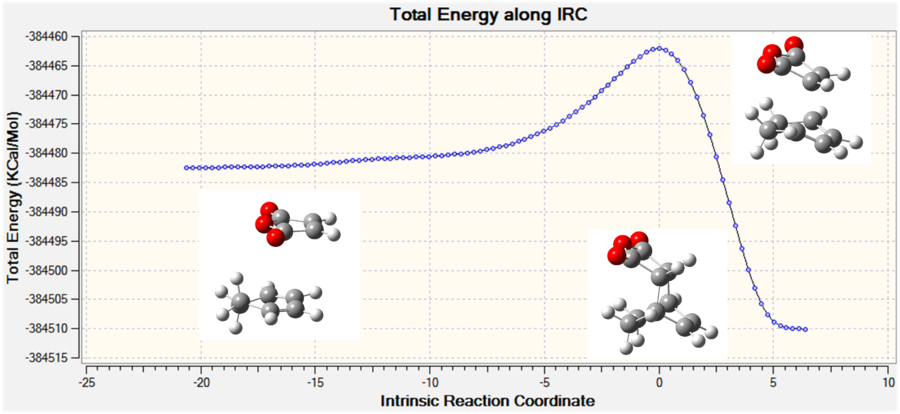

It was found in the first section that the best method for IRC was to calculate the force constants at each step. Therefore this was done for the reaction of cis-butadiene with ethene at the B3LYP/6-21G(d) level of theory with a maximum of 100 steps in both directions from the transition state. The calculation stopped after 72 steps at which the RMS of the gradient was close to zero, signifying the calculation had gone to completion. An animation of the reaction progress is shown in figure 17.

|

|

| Figure 16: The energy and RMS of the IRC[46] of the reaction of cis-butadiene with ethene | |

It can be seen from the energy graph that the reactants are higher in energy than the products - indicating that the reaction is exothermic, this is in agreement with literature[47].

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

As mentioned before, there are two possible regioisomeric products of Diels-Alder cycloadditions of substituted alkenes - exo- and endo- (figure 18).

It has been found experimentally that it is solely the endo isomer that is formed. Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride will be used to model the Diels-Alder reaction computationally to investigate the reasons for the high regioselectivity.

Optimisation of the Reactants

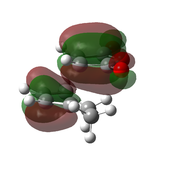

The reactants, cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride, were optimised as before using the semi-empirical method AM1 and the B3LYP/6-21G(d) level of theory. Their HOMO's and LUMO's were visualised to establish how the reaction might proceed.

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene does not have a σv plane of symmetry, therefore its MOs are not perfectly symmetric, however they have been labelled symmetric and asymetric with respect to the distribution of the orbitals at the diene. The AM1 method produced orbitals which suggest that an interaction is possible between the LUMO of A and HOMO of B and vice versa, however the orbitals produced by the B3LYP/6-21G(d) method suggest that only an interaction between the HOMO of A and LUMO of B is possible as they have the correct symmetry. This is also confirmed by the smaller energy difference between the HOMO of A and LUMO of B (0.08841 eV) which is smaller than that of the LUMO of A and HOMO of B (0.28215 eV). This is to be expected as the LUMO of maleic anhydride is lowered by the interaction of the electron withdrawing carbonyls with the alkene.

The MOs derived from the B3LYP/6-21G(d) method also show that much of the electron density is focused on the alkene of maleic anhydride in the LUMO (c.f. the HOMO where is centralised on the carbonyls).

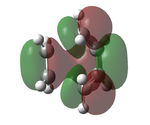

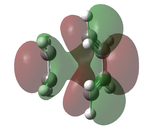

Optimisation of the Transition State

The transition state was optimised using the same technique used for ethene and butadiene.

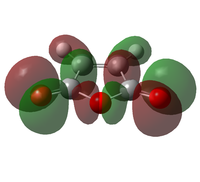

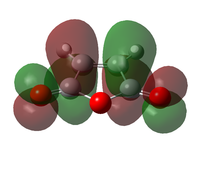

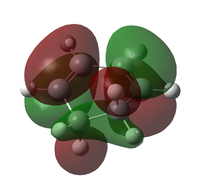

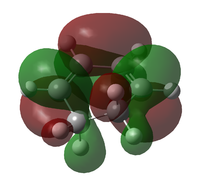

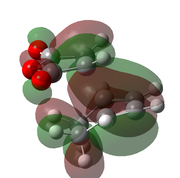

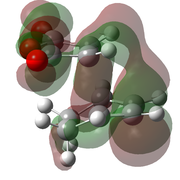

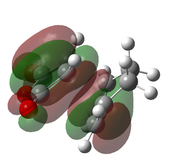

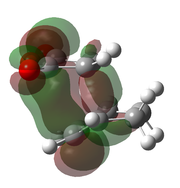

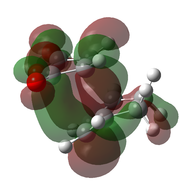

| Method | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+2 | Energy / Hartrees | Negative Vibration / cm-1 | Pictorial Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1[48] |  |

|

|

|

-0.0504199 | -811 |  |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d)[49] |  |

|

|

|

-612.679 | -449 |  |

| Method | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+2 | Energy / Hartrees | Negative Vibration / cm-1 | Pictorial Representation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1[50] |  |

|

|

|

-0.051505 | -806 |  |

| B3LYP/6-31G(d)[51] |  |

|

|

|

-612.683 | -447 |  |

The optimised transition states suggest that it is the endo form that is lower in energy (by 10.7 kJ mol-1 for the B3LYP/6-21G(d) optimised forms). This was expected as it is the endo isomer that is formed experimentally. The extra stabilisation arises from the interaction of the carbonyl π* orbitals and the п-orbital of the developing double bond. These interactions may be observed in the LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 orbitals of the endo transition state, yet it is not present in the exo form. However as these orbitals are not filled, there may be other factors contributing to the relative stability of the endo transition state.

Another factor may be steric repulsion, this may be analysed by looking at the bond lengths in both transition states.

| Method | Isomer | Cyclohexadiene (C=C) | Cyclohexadiene (C-C) | Maleic Anhydride (C=C) | Forming C-C | Repulisve C-C | Forming C-C-C bond angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM1 | exo | 1.39 | 1.52 | 1.41 | 2.21 | 2.95 | 99.8° |

| endo | 1.39 | 1.52 | 1.41 | 2.16 | 2.89 | 94.8° | |

| B3LYP/6-21G(d) | exo | 1.39 | 1.56 | 1.40 | 2.29 | 3.03 | 99.2° |

| endo | 1.39 | 1.56 | 1.39 | 2.27 | 2.99 | 94.2° |

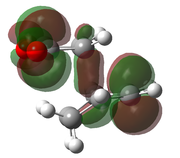

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Exo (AM1) | Endo (AM1) | Exo (B3LYP/6-21G(d)) | Endo (B3LYP/6-21G(d)) |

It can be seen that the bond lengths in the exo and endo transition states are relatively similar, however the bond forming lengths are slightly different. In the endo transition state the bond forming length is shorter, this can be attributed to the attractive interaction between the carbonyls and the forming double bond discussed above. There is a repulsive interaction between the carbonyl carbon and the tetrahedral carbon of the cyclohexadiene in the exo form and the sp2 carbon in the endo form. This distance is longer in the exo form, this could be accredited to the greater steric bulk of the sp3 carbons and the hydrogen atoms in between these two carbons. It can be seen from the bond angle between the forming carbons that the bond angle for the exo form is greater, suggesting that the interaction is more strained as it is avoiding the steric repulsion.

IRC Analysis

Although the endo transition state is lower in energy, this is by a relatively small amount, and there is often also some degree of error in the calculations. Therefore the IRC will be calculated to investigate whether the activation energy is a contributing factor to the regioselectivity of the reaction.

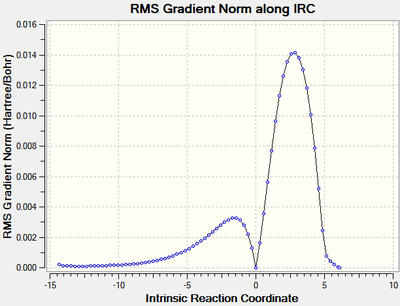

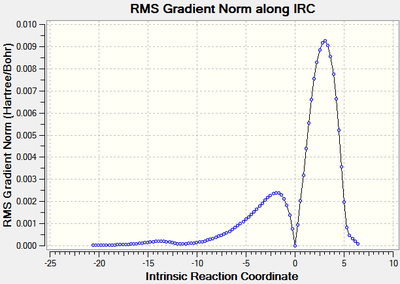

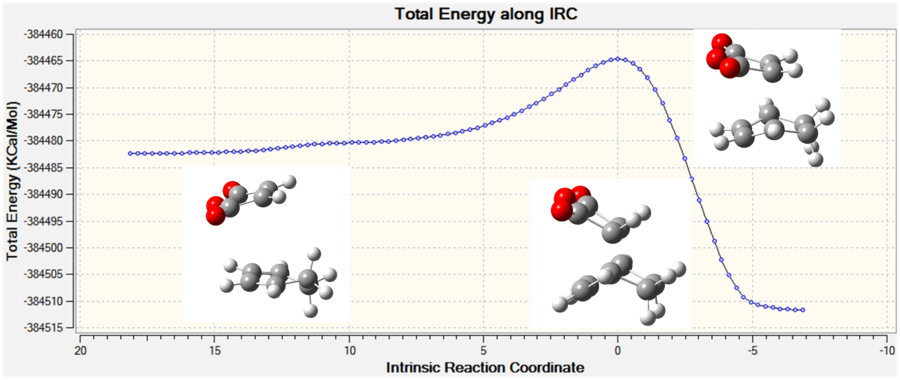

The IRC was run with a maximum of 100 steps, in both directions and with force constants calculated at each step at the B3LYP/6-21G(d) level of theory. Both calculations stopped before the 100 steps were completed and the RMS of the energy of the IRC was close to zero at both the product and reactant end. The the forward direction of the endo form produced the reactants, therefore the scale of the graph was inverted along the x-axis so it represented the true reaction coordinate. Again the reactions were exothermic which is expected.

| |

| |

| Figure 19: The energy and RMS of the IRC[52] of the exo transition state. | |

| |

| |

| Figure 20: The energy and RMS of the IRC[53] of the endo transition state. | |

|

|

| Figure 21: The progress of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition via the exo and endo transition state. | |

The reactant and product geometries were further optimised at the B3LYP/6-21G level of theory and their energies were used to calculate the activation energy of the reaction and the change in free energy ΔG of the reaction.

| Transition State | Transition State Energy[.log file] / Ha | Product Energy[.log file] / Ha | Reactant Energy[.log file] / Ha | Ea / Ha | ΔG / Ha | Ea / kJ mol-1 | ΔG / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | -612.67931091[54] | -612.75578545[55] | -612.71177231[56] | 0.0324614 | -0.04401314 | 85.23 | -115.56 |

| Endo | -612.68339676[57] | -612.75829018[58] | -612.71154769[59] | 0.02815093 | -0.04674249 | 73.91 | -122.72 |

It can be seen from the table above that the activation energy for the reaction of maleic anhydride with cyclohexadiene is larger for the formation of the exo isomer than the endo isomer by 11.32 kJ mol-1 indicating that the formation of the endo isomer is the kinetically favoured pathway - resulting in a regioselective product.

It was expected that the exo isomer would be more thermodynamically stable that the endo, however the computational analysis predicts differently. The difference in energy is small (6.6 kJ mol-1) so there may be some degree of error.

Conclusions

It was found that in the Diels-Alder reaction between cis-butadiene and ethene that it was more likely to occur due to the interaction between the HOMO of cis-butadiene and the LUMO of ethene as the difference in energy between these two orbitals compared to the energy difference between the LUMO of butadiene and HOMO of ethene, despite this overlap being symmetry allowed. The transition state was successfully optimised and IRC calculated - confirming that the reaction is an exothermic process.

The reaction between maleic ahnydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene was used to investigate the regioselectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction. The endo transition state was found to have a lower energy than the exo form. The additional energy was attributed to the steric strain of the approach of the maleic anhydride towards the sp3 hybridised carbons on the cyclohexadiene ring. The IRC was calculated for both isomers, and it was found that the endo reaction path had a lower activation energy - explaining the regioselectivity.

This study has shown that computational methods may be successfully used to calculate the geometry of transition states of simple pericyclic reactions where the approximate structure of the transition state is known. Consequently kinetic information may be computed once the transition state structure is known. This could theoretically be extended to more complex reactions, however this may be computationally expensive.

This study could be extended to investigate the effect of electron withdrawing and donating substituents on the diene and dienophile to establish a trend between the activation energy and the relative energies of the HOMO and LUMO concerned.

References

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13225

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13226

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13227

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13228

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13230

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13229

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13231

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13232

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13233

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13234

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13262

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13263

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13264

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13265

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13266

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13267

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13307

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13306

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13305

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13335

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13339

- ↑ M. J. S. Dewar and E. F. Healy, Chem. Phys. Lett., 1987, 141, 521–524

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13398

- ↑ Pure Appl. Chem., 1999, 71, 1919-1981 DOI:10.1351/pac199971101919

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13411

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13412

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13413

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13505

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13414

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13549

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13550

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13551

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13505

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13553

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13554

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13558

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13557

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13559

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13560

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13645

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13645

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13561

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13644

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13646

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13647

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13546

- ↑ M. A. Fox, J. K. Whitesell, in Organic Chemistry, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2004, 3rd edn.

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13642

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13640

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13643

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13641

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13638

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13639

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13640

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13636

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13635

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13641

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13637

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-13634