Rep:Mod:Ellyn

Ellyn Junker 00602040

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene

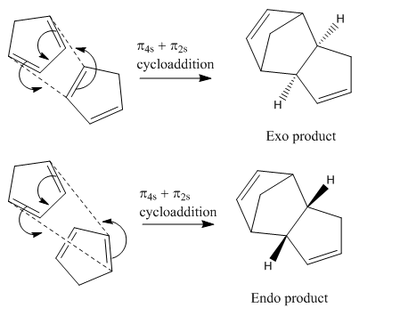

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is an example of a Diels Alder π4s + π2s cycloaddition. There are theoretically two possible isomers that could be formed, the exo (1) and the endo (2) dimer.

The MM2 function in ChemBio3D Ultra is an example of a molecular mechanics model which is essentially a non-quantum mechanical model. It calculates molecular properties based on some fundamental equations[1] (for example Hookes Law and Colombic potentials) in a fast, simple manner; whereas calculating such properties quantum mechanically requires enormous computing power and usually gives an inaccurate result. Molecular mechanics may be used to determine a molecule's optimal geometry and can compute it's minimum energy. Therefore the energies of two isomers may be compared to establish the more thermodynamically stable isomer (table 1). This has been carried out for the exo and endo form of dicyclopentadiene.

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | |||

| Exo dimer (1) | Endo dimer (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2855 | 1.2507 | |

| Bend | 20.5794 | 20.8476 | |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8381 | -0.8358 | |

| Torsion | 7.6571 | 9.5109 | |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.4171 | -1.5430 | |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.2322 | 4.3195 | |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3776 | 0.4476 | |

| Total Energy | 31.8766 | 33.9975 | |

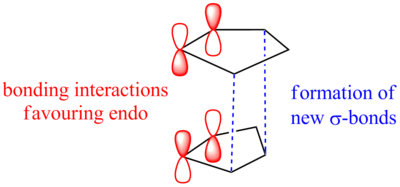

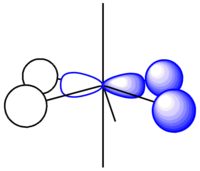

It can be seen from the results that the exo form is in fact lower in energy, however it is widely known that it is solely the endo dimer that is formed[2]. The reaction goes through a transition state where favourable bonding interactions occur between the π* orbitals on both of the cyclopentadiene molecules when in the correct orientation to form the endo dimer (figure 2). This lowers the activation energy of the reaction and encourages the endo isomer to form. No such interactions can occur when the two molecules are in the orientation that forms the exo isomer. In such, Molecular Mechanics cannot be used in all cases to predict the product of a reaction as this is not always the most thermodynamically stable and it does not take into account the secondary interactions during a reaction.

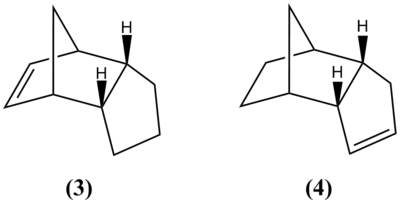

The product of dimerisation may be hydrogenated, a dihydro derivative may be obtained by keeping the reaction time short as continued hydrogenation gives the tetrahydro derivative. There are two possible products of dihydrogenation (3) and (4), however the reaction tends to be regioselective, largely due to the difference in energies of the products. Table 2 shows that (4) is in fact lower in energy and hence more stable, therefore if the reaction were to proceed thermodynamically this would be the predominant product.

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (3) | (4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2357 | 1.0963 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bend | 18.9412 | 14.5207 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stretch-Bend | -0.7611 | -0.5494 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Torsion | 12.1224 | 12.4982 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.5028 | -1.0668 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1,4 VDW | 5.7281 | 4.5125 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1631 | 0.1406 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total Energy | 35.9266 | 31.1520 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The results show that the main source in the difference in energies is the bending energy, this arises as a result of angular strain. The calculated bond angles of the sp2 carbons in (3) and (4) shows that the sp2 angles in (4) (112.4°) are much closer to the ideal (120°) than in (3) (107.6°), therefore the ring strain is much higher in energy (difference of 4.4205 kcal mol-1) in (3) than in (4). The Van der Waals forces, stretching and dipole-dipole interactions in (4) are lower in energy, also contributing towards its stability. The torsional forces are higher in energy in (4), however the small energy difference (0.3758 kcal mol-1) is not enough to outweigh the other molecular interactions.

Stereochemistry and the reactivity of an intermediate in the synthesis of taxol

Stereochemistry

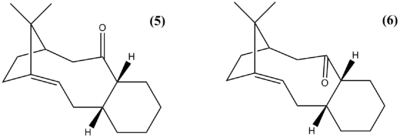

Taxol is a natural compound from the bark of the Pacific Yew tree Taxus brevifolia used in the treatment of cancer. Therefore the development of synthetic routes for this compound has been of interest to the pharmaceutical industry. The compounds (5) and (6) are key intermediates in the total synthesis of taxol that was proposed by Paquette[3]. They are atropisomers due to the the steric strain barrier to rotation about the single bonds. It is (5) that is initially formed, however when left to stand it converts to (6). This indicates that (6) is more thermodynamically stable and (5) is formed via the kinetic pathway. The minimum energies of (5) and (6) were calculated (table 3), these were both when the 6-membered ring was in the chair conformation.

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | ||

| (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.7833 | 2.6193 |

| Bend | 16.5389 | 11.3356 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.4303 | 0.3429 |

| Torsion | 18.2525 | 19.6702 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.5504 | -2.1558 |

| 1,4 VDW | 13.1100 | 12.8730 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.7250 | -2.0024 |

| Total Energy calculated with MM2 | 47.8396 | 42.6829 |

| Total Energy calculated with MMFF94 | 70.5012 | 60.5621 |

The results from both the MM2 and MMFF94 model show that (6) is more thermodynamically stable, the main contribution to its stability (cf (5)) is the triatomic bending interactions. Upon inspection of the geometry of (5) and (6), it can be seen that the hydrogen on the tri-substituated carbon adjacent to the carbonyl is antiperiplanar to the C=O bond in (6), whereas in (5) is is synperiplanar which is more unfavourable.

Reactivity and Hyperstable Alkenes

The tricylics (5) and (6) have a strained bridgehead due to the presence of the double bond. The work of Bredt [4] suggested that bridgehead double bonds were impossible due to their high reactivity. However, since then stable bridgehead double bonds have been synthesised, albeit in larger ring systems which can accommodate the strain[4]. These types of molecules are unreactive towards hydrogenation due to their negative 'olefinic strain' energy, which is the difference between the total energy of the olefin and the total energy of its hydrogenated derivative[5]. The total energy of the hydrogenated derivative of (6) was calculated using MM2 and MMFF94, and compared with the total energy of (6) (table 4).

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | |||

| (6) | hydrogenated derivative of (6) | Energy Difference (alkene-hydrogenated alkene) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.6193 | 3.0712 | -0.4519 |

| Bend | 11.3356 | 14.5379 | -3.2023 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3429 | 0.5703 | -0.2274 |

| Torsion | 19.6702 | 21.3267 | -1.6565 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.1558 | -0.6560 | -1.4998 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.8730 | 14.8074 | -1.9344 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -2.0024 | -1.7385 | -0.2639 |

| Total Energy calculated with MM2 | 42.6829 | 51.9191 | -9.2362 |

| Total Energy calculated with MMFF94 | 60.5621 | 73.7336 | -13.1715 |

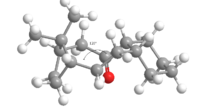

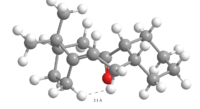

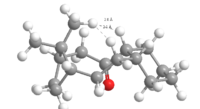

Both values calculated using MM2 and MMFF94 show that (6) has negative olifinic strain energy (-13.2 kcal mol-1). The major contributor to this difference is again the bend energy. In the hydrogenated product, the sp3 carbon (highlighted in figure 6) is highly strained from its ideal geometry (bond angles at 109.5°) with a C-C-C bond angle of 120°. The same C-C-C angle in the olefin however is similar to the hydrogenated molecule (124°) yet the carbon centre is sp2 hybridised and therefore actually quite close to the ideal geometry of 120°.

|

|

There is also a fairly high contribution to the olefinic strain energy from the 1,4 and non-1,4 Van der Waals interactions. When the distance between two non bonded atoms is equal to or less than 2.1 Å the interaction becomes repulsive. One of these repulsive interactions arises in (6), however there are two in its hydrogenated derivative, contributing to its higher energy.

|

|

Modelling using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

The Molecular Mechanics method of analysing molecules is sufficient for simple, small molecules that do not contain any heteroatoms. For larger molecules that have complex intramolecular interactions, the MM model becomes increasingly inaccurate. Therefore the more complex semi-empirical Molecular Orbital theory must be used, this takes the form of MOPAC and Gaussian models in computational modelling. Not only can these methods be used to find minimum energies and optimal geometries, they may be used to predict spectroscopic data and reaction mechanisms.

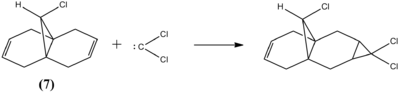

Regioselective addition of Dichlorocarbene

Carbenes are highly reactive species, upon reaction with 9-chloromethanonapthalene (7), dichlorocarbene electrophillically adds to one of the alkenes within the molecule. This regioselective addition is controlled by the π-orbitals. In order to understand the reasons for this regioselectivity, an approximate representation of the valence-electron molecular wavefuntions was determined.

Orbital Control of Reactivity

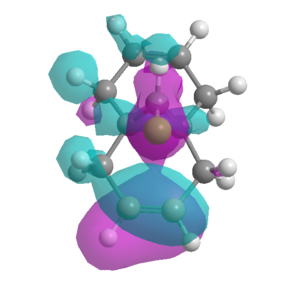

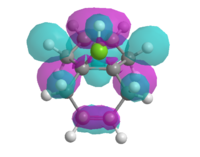

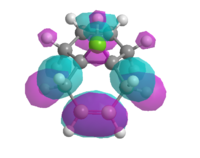

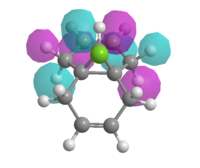

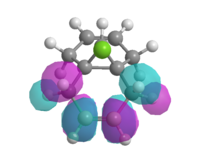

The MM2 force field was first used to optimise the geometry of (7), the molecular orbital surfaces were then determined using the MOPAC/PM6 interface. The HOMO calculated (figure 10) did not display the same symmetry as the molecule which has a point group of Cs and therefore displays a σh plane of symmetry. Therefore it was presumed that this was not an accurate enough representation of the molecular orbitals to proceed with the experiment.

Therefore the MOPAC/PM3 interface was used, which gave highly symmetrical representations of the molecular orbitals. This was used to model the HOMO, HOMO-1, LUMO, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 orbitals (figure 11).

| HOMO -1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO + 1 | LUMO + 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| Figure 11: Valence-electron molecular wavefunctions of (7) modelled using MOPAC/PM3 | ||||

It was assumed that the HOMO would be most reactive towards electrophilic attack as the electrons within the orbital are highest in energy. It is clear from the model of the HOMO that the C=C double bond syn to the chlorine has a large build up of electron density, therefore must be most prone to electrophilic attack by the carbene as the high energy electrons in the π bond form a σ-bond to the carbene.

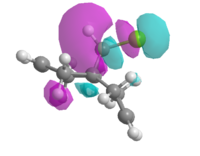

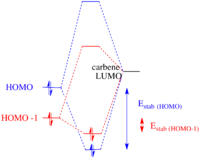

The HOMO-1 orbital has most of its electron density located on the alkene anti to the carbene, therefore it may be thought that it would also act as a good nucleophilic centre for a reaction with the carbene. However as the electrons within this orbital are lower in energy than those in the HOMO, the stabilisation effect encountered upon reaction with the carbene is sufficiently lower than the stabilisation energy when the HOMO reacts with the carbene for one product to be dominant. This effect is described by the Klopman Salem equation: Estab α S2 / ΔEi. Therefore, the smaller the difference in interaction energy between the orbitals of the alkene and the LUMO of the carbene, the higher the stabilisation energy (figure 12).

On the other hand, if (7) were to undergo nucleophilic attack, this would probably proceed on the anti alkene as most electron density is located here in the LUMO.

It can be seen in the image of the LUMO+2 a strongly antibonding orbital associated with the C-Cl bond, suggesting this is the σ*C-Cl orbital. As the chlorine is electronegative, this orbital may act as a good electron acceptor, therefore stabilising the anti alkene via electron donation from the π-bond into the σ*C-Cl.

Influence of the Cl-C bond on vibrational frequencies

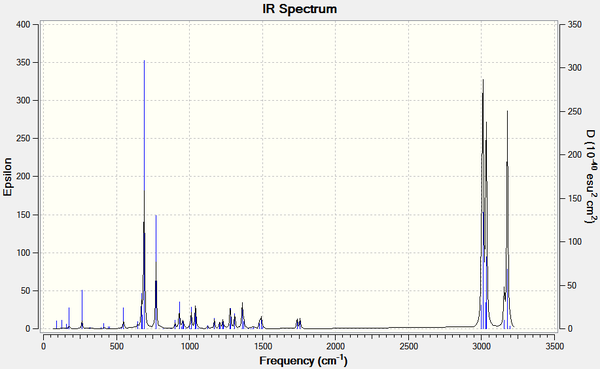

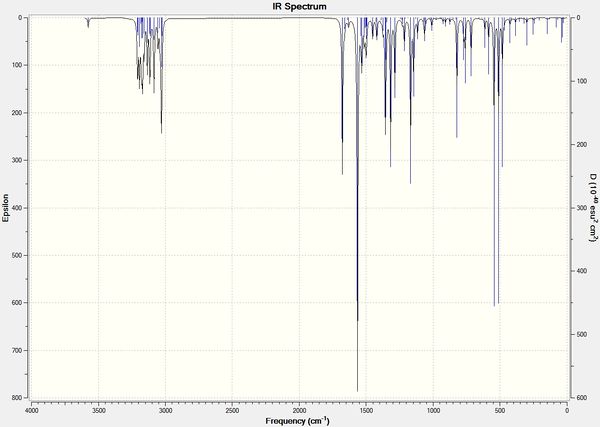

The vibrational frequencies of (7) and its dihydro derivative (the alkene anti to the chlorine being hydrogenated) were calculated. Their geometries were first optimised using MM2 and then MOPAC/RM1, and then subjected to B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation which was run on SCAN. The results were analysed on GaussView 5.0.9 and the vibrational spectra shown in figure 13 were produced.

|

| |||

| Figure 13: IR spectra of (7) and its dihydro derivative calculated using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation function | ||||

It can be seen that the frequency of the C-Cl stretch in the dihydro derivative (780.06 cm-1) is higher than in (7) (770.86 cm-1), indicating that the bond is stronger in the dihydro derivative. By referring to the valence electron molecular wavefunctions produced for (7) (figure 11), the increase in C-Cl bond strength may be rationalised. The interaction between the σ*C-Cl (seen in the LUMO+2) and the π-bond of the alkene anti to the Cl (as discussed above) is lost in the dihydro derivative, therefore the electron density in the σ*C-Cl orbital is decreased, strengthening the C-Cl bond.

It can be also seen in the IR spectrum of the dihydro derivative the loss of one vibration around 1740 cm-1 which corresponds to a C=C stretching frequency, due to the hydrogenation of one of the alkene bonds.

| Frequency (cm-1) | ||

| Bond vibration type | (7) | Dihydro derivative |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl | 770.86 | 780.06 |

| C=C (syn) | 1757.35 | 1753.75 |

| C=C (anti) | 1737.04 | n/a |

Glycosidation

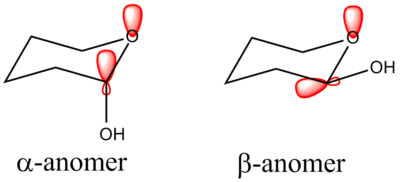

Substituents on cylcohexane rings generally prefer to adopt an equatorial position rather than axial to avoid 1,3-diaxial interactions which are energetically unfavourable. Monosaccharides in their cyclic form contain an oxygen atom in a 5- or 6-membered ring. The oxygen induces a stabilising effect for the substituent in the axial position on the adjacent carbon, in the case of naturally occurring monosaccharides this is a hydroxy group. This is due to what is known as the anomeric effect. When the substituent is in the axial position (α-anomer), the oxygen lone pair may donate some of its electron density into the relatively low energy σ*C-O orbital, hence resulting in a stabilising effect that outweighs the unfavourable 1,3-diaxial repulsions. This stabilisation effect is not possible in the β-anomer due to poor nOlp→σ*C-O orbital overlap. In addition, the overall dipole invoked by having the OH group equatorial is larger than if it were axial, also disfavouring the β-anomer.

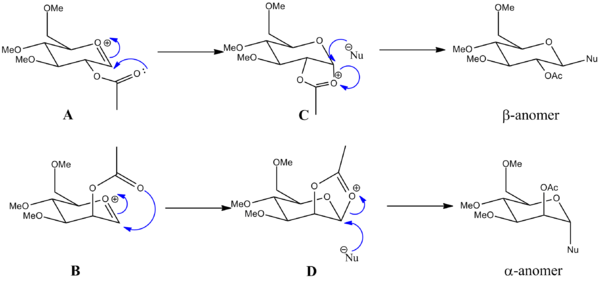

Obtaining the β-anomer can therefore be difficult as a straightforward nucleophilic attack will give predominantly the α-anomer. Therefore a neighboring group participation strategy must be used. By blocking the bottom face of the 6-membered ring with an acetyl group, nucleophiles are forced to attack via the top face and the β-anomer is formed. This method can also be used to produce exclusively the α-anomer by blocking the top face.

Neighbouring group participation of glycosidation was investigated using molecular mechanics modelling (MM2) and the semi-empirical molecular orbital theory employed by the MOPAC/PM6 model. The ring substituents chosen was OMe to keep computational demand at a minimum (OAc would invoke complex interactions) but still achieving a like-for-like representation of the steric demand (OH is not sterically demanding enough). MM2 was used to initially optimise the geometry of the isomers, and then MOPAC/PM6 was used to model the neighbouring group participation as it is able to take into account more complex bonding interactions than MM2 (which is essentially only suitable for very simple molecules). A and A' has the OAc group in the equatorial position, it being above the ring in A and below in A'. B and B' has the OAc group in the axial position, it being above the ring in B and below in B'. Their corresponding products are named (reactant): C (A), C' (A'), D (B) and D' (B').

| Energy of isomer in (kcal/mol) | ||||||||

| A | A' | B | B' | C | C' | D | D' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.5979 | 2.4488 | 2.8235 | 2.4265 | 1.9908 | 1.8910 | 2.1099 | 1.9884 |

| Bend | 9.2072 | 11.6976 | 14.6514 | 9.4701 | 14.4159 | 14.1528 | 16.2422 | 11.4200 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.9473 | 0.8835 | 1.1541 | 0.9207 | 0.8036 | 0.6196 | 0.7582 | 0.6069 |

| Torsion | 0.5942 | 0.3894 | 2.4604 | 1.5477 | 7.9349 | 6.2429 | 7.9861 | 9.7757 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.6587 | -1.9036 | 0.3273 | -4.0935 | -3.4725 | -3.7388 | -3.6577 | -4.1381 |

| 1,4 VDW | 18.2980 | 18.4054 | 18.5898 | 18.8332 | 17.2346 | 17.7657 | 17.5430 | 19.2866 |

| Charge/Dipole | 0.5497 | -11.0951 | -7.8391 | 6.6075 | 0.1298 | 1.5063 | 2.9434 | -6.6917 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 6.7346 | 6.4598 | 4.7220 | 4.0930 | -0.9075 | -1.7788 | -0.2562 | -0.4471 |

| Total Energy calculated with MM2 | 36.2701 | 27.2858 | 36.8894 | 39.8052 | 38.1296 | 36.6607 | 43.6689 | 31.8007 |

| ΔH energy of formations calculated with MOPAC/PM6 | -91.66259 | -63.61318 | -89.96374 | -69.48471 | -90.73132 | -67.81175 | -90.51326 | -71.53418 |

When the OAc group is in the equatorial position, the molecule is lower in energy when the group is below the plane of the ring (A). The energy of the corresponding product (C) is very similar, implying the electron distribution in the PM6 model of A is similar to that in the product C. The distance between the carbonyl oxygen on the acetyl group and the carbonyl carbon in the ring in A is 1.6 Å and in C the distance between the corresponding atoms is 1.5 Å. This implies that a bond has essentially been formed quantum-mechanically between these two atoms in A. The distance between the same bonds in A' is 4.3 Å, clearly in this model formation of a bond is unfavourable. This is reflected in the energy of its corresponding product (C'), -67.81175 kcal mol-1 which is much lower than the energy of C. The angle between the carbonyl in the ring and the acetyl oxygen is 104.7° which is close to the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory angle for nucleophilic attack of carbonyls (107°). These results indicate that with the acetyl in the equatorial position, it is preferred that the acetyl protects the bottom face and hence the β-anomer may be obtained.

Conversely, when the OAc group is in the axial position, orientating the group above the plane of the ring (B) is energetically preferred (heat of formation is -89.96374 kcal mol-1) compared to the group being below the plane of the ring in B' (-69.48471 kcal mol-1). Again, as for A, the distance between the acetyl oxygen and ring carbonyl carbon is relatively similar in B (1.56 Å) as it is in the product D (1.55 Å). Whereas the distance in B' is much greater (3.95 Å) indicating that formation of a σ-bond is unfavourable (c.f. B).The energy for the products corresponds to this, the energy for D (-90.51326 kcal mol<sup?-1) being lower than for D' (-71.53418 kcal mol<sup?-1). Thus, the correct orientation for neighbouring group participation is when the acetyl group in on the top face, so that the α-anomer is formed.

Mini Project - Intermolecular Hydroamination of Alkynes

Introduction

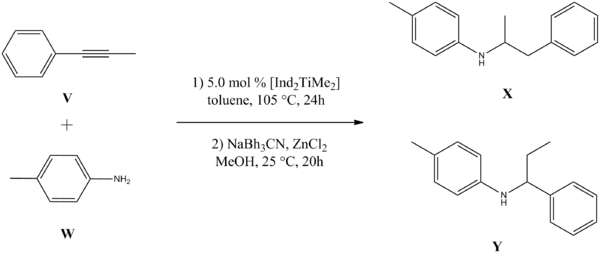

The hydroamination of alkynes may be carried out by the transition metal catalyst [Ind2TiMe2]. The reaction of unsymmetric 1-aryl-2-alkylalkynes invokes high regioselectivity with the anti-Markovnikov regioisomer being the predominant product. The reaction of 1-phenylpropyne V and 4-methyl aniline W gives the two products X and Y with the ratio X:Y 49:1[8] (figure 16). Analytical computational methods may be used to generate spectroscopic data for the two isomers in order to distinguish the difference between them, and they can also be compared with literature values.

Analysis of Energies

The energies of the two regioisomers X and Y were minimised and geometries optimised using MM2 and MOPAC/PM6. The structures of the MM2 optimised geometries were not markedly different to those calculated with MOPAC/PM6, however the total energies showed that with the MOPAC/PM6 model X is more thermodynamically stable which contradicts the MM2 calculations which suggests Y is lower in energy.

| Energy in (kcal/mol) | |||

| X | Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 0.7840 | 0.7641 | |

| Bend | 2.0044 | 2.1253 | |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.0851 | 0.0777 | |

| Torsion | -14.1091 | -13.9094 | |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.7238 | -3.0824 | |

| 1,4 VDW | 14.2407 | 13.8164 | |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1148 | -0.4530 | |

| Total Energy calculated with MM2 | 0.3960 | -0.6613 | |

| Total Energy calculated with MOPAC/PM6 | 24.40545 | 27.43297 | |

Literature[8] reports that X is the predominant isomer with a ratio of X:Y 49:1. Even though the predicted thermodynamic data suggests that X is the more thermodynamically stable isomer, the difference in energy (calculated with MOPAC/PM6) is small (-3.02752 kcal mol-1), and therefore cannot rationalise the large ratio. This suggests that the stability of the metallocycle intermediate formed upon cycloaddition of the alkyne to the titanoimine is a major contributing factor to the final product (figure 17).

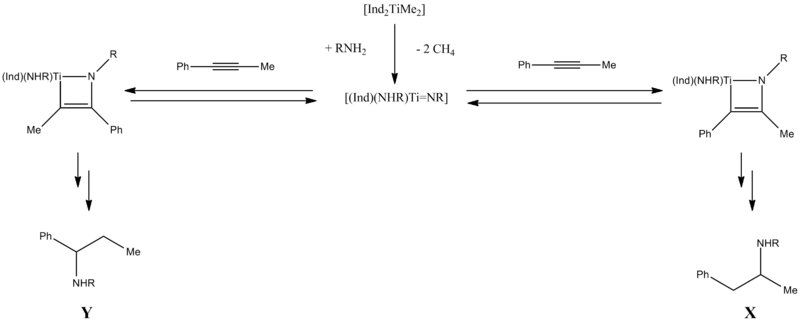

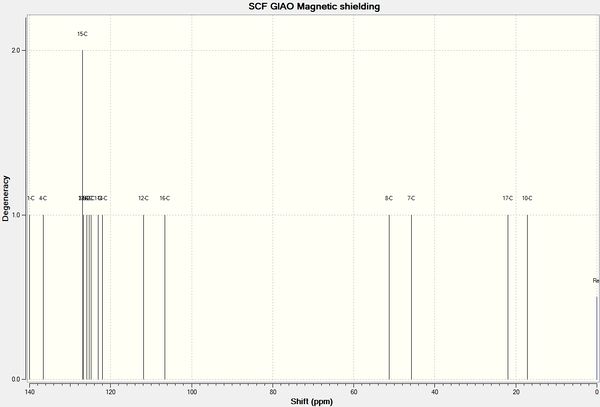

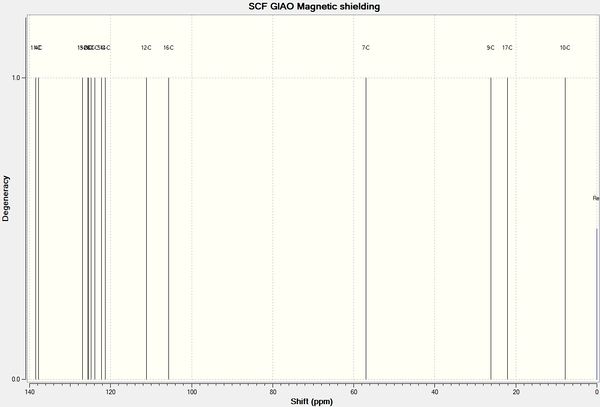

13C NMR spectral analysis

The MOPAC/PM6 optimised geometries of X and Y were further optimised by DFT mpw1pw91/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian on SCAN. The NMR shifts were then calculated with chloroform as the theoretical solvent.

|

| |||

| Figure 18: NMR spectra of X and Y calculated using mpw1pw91/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation function, reference = TMS mPW1PW91/6-31G(d,p) CDCl3 GIAO | ||||

| X 13C Chemical Shift (δ, ppm) | Y 13C Chemical Shift (δ, ppm) | |||||||

| Environment | Predicted | Literature[8] | Difference | Environment | Predicted | Literature[8] | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 139.5 | 145.0 | -5.5 | 11 | 139.3 | 145.3 | -6.0 | |

| 4 | 136.2 | 138.7 | -1.5 | 4 | 138.6 | 144.1 | -5.5 | |

| 3 | 126.5 | 129.9, 129.5, 128.3 and 126.2 | - | 15 | 127.8 | 129.6, 128.4, 126.8 and 126.5 | - | |

| 15 | 13 | 127.7 | ||||||

| 13 | 126.3 | 2 | 126.5 | |||||

| 5 | 125.4 | 3 | 126.3 | |||||

| 6 | 124.9 | 6 | 125.6 | |||||

| 2 | 124.4 | 1 | 124.7 | |||||

| 1 | 122.6 | 5 | 123.1 | |||||

| 14 | 121.6 | 126.4 | -4.8 | 14 | 122.1 | 126.2 | -4.1 | |

| 12 | 111.4 | 113.7 | -2.3 | 12 | 112.0 | 113.4 | -1.4 | |

| 16 | 106.2 | - | - | 16 | 106.5 | - | - | |

| 8 | 50.9 | 49.7 | +1.2 | 7 | 57.8 | 60.0 | -2.2 | |

| 7 | 45.3 | 42.4 | +2.9 | 9 | 27.0 | 31.7 | -4.7 | |

| 17 | 21.6 | 20.4 | +1.2 | 17 | 22.8 | 20.3 | +2.5 | |

| 10 | 16.7 | 20.2 | -3.5 | 10 | 8.7 | 10.8 | -2.1 | |

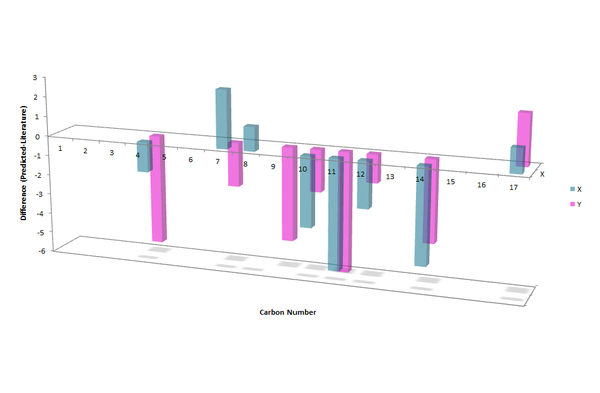

Only 4 peaks were reported in the literature for the aromatic carbons for both X and Y, however 6 separate peaks were calculated for X and 7 for Y. Carbons in aromatic rings tend to have very similar chemical shifts, so they can become indistinguishable, which would account for the lack of peaks reported in literature. There is no reported peak in literature for C16 for either molecule, the calculated value (~106 ppm) is close to the value for C12 (~111 ppm) as they are in very similar environments, therefore in the experimental spectrum the two peaks may be indistinguishable. The differences between the literature and calculated values are displayed in the chart in figure 19, the largest difference is 6.0 ppm (C11 in Y). The majority of the calculated peaks have a lower chemical shift value than those reported in literature

The aliphatic methine carbon in X (C8, 49.7 ppm) and Y (C7, 60.0 ppm) has a large difference in chemical shift in the literature spectra (10.3 ppm). This difference is also reflected in the calculated values: X = 50.9 ppm and Y = 57.8 ppm; difference = 6.9 ppm. Thus the calculated NMR spectra may be used to distinguish between the two regioisomers.

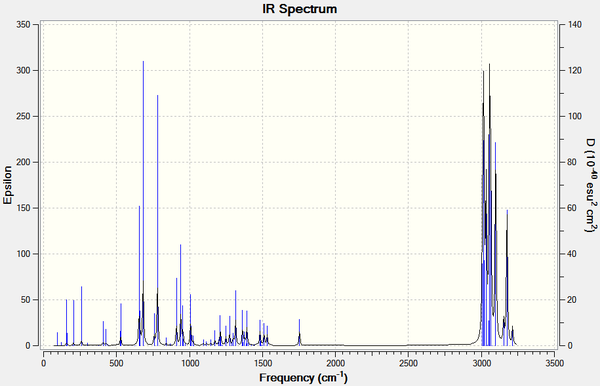

IR spectral analysis

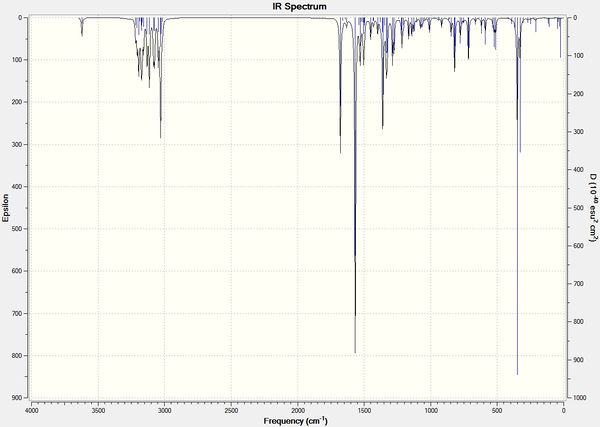

The IR spectra were calculated as for the NMR except using the B3LYP DFT function.

|

| |||

| Figure 20: IR spectra of X and Y using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimisation function | ||||

| X Frequencies / cm-1 | Y Frequencies / cm-1 | |||

| Bond Vibration Type | Calculated | Literature[8] | Calculated | Literature[8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-H | 3576 | NR | 3620 | NR |

| C-H benzene symmetric stretch | 3208 | NR | 3216 | NR |

| 3205 | 3205 | |||

| C-H benzene asymmetric stretch | 3193 | NR | 3194 | NR |

| 3177 | 3185 | |||

| 3169 | 3176 | |||

| 3158 | 3156 | |||

| Methyl C-H stretch | 3134 | NR | 3113 | NR |

| 3112 | 3082 | |||

| 3088 | 3046 | |||

| 3032 | 3030 | |||

| Methylene C-H stretch | 3080 | 2920 | 3074 | 2963 |

| 3024 | 3026 | 2921 | ||

| Aromatic C-C | 1678 | 1617 | 1679 | 1618 |

| 1564 | NR | 1529 | NR | |

| 1532 | 1517 | 1566 | 1518 | |

| 1451 | 1452 | 1451 | 1452 | |

| C-N stretch | 1168 | 1150 | 1165 | NR |

| 1142 | ||||

| Mono-substituated benzene C-H bend | 772 | 743 | 777 | 749 |

| 699 | 716 | 700 | ||

| Para-substituated benzene C-H bend | 822 | 805 | 820 | 805 |

There is very little difference between the calculated spectra of X and Y, they are also inconsistent with the reported literature values. The calculated values are closer to the literature values for the bending vibrations in the low frequency region. The errors for the stretching frequencies (in the higher frequency region) are very high with some differences over 100 cm-1.

The large errors and the fact that the calculated spectra are very similar makes this an unreliable technique for analysing X and Y. This may be a good technique however for molecules with largely different bending frequencies.

The .out output file from the Gaussian IR calculations also gave the calculated sum of electronic and thermal free energies for X and Y. These values were compared and X was found to be more stable with a lower energy of -1.218 kcal mol-1. This agrees with the conclusions drawn from the analysis of the energies with MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 which also predicted that X has a lower energy than Y, albeit the energy difference calculated with MOPAC/PM6 was the ΔH of formation.

Optical Rotation

The optical rotation for X and Y was found by inputting the keyword CPHF=RdFreq into the output file obtained from the NMR optimisation. The wavelength of the incident light was specified as 589 nm.

| Optical rotation [α]TD with T in units of °C | ||

| Compound | Computational Result (T) | Literature |

|---|---|---|

| X | -15.34 (25)[13] | 0.7641 (19)[14] |

| Y | -59.45 (25)[15] | NR |

The calculated optical rotation for X is comparable with the value found in literature. There is some difference, however the temperature the experimental value was taken at (19 °C) is lower than the theoretical temperature (25 °C) and optical rotation is related to temperature. There was unfortunately no value reported for Y in literature, therefore no comparison could be made, however this could be an accurate method for distinguishing between two isomers.

No distinction could be made between the two molecules with analysis of the circular dichroism as the optimised structures of X and Y both had negative optical rotation.

Conclusion

From this computational analysis of the two regioisomers X and Y, it can be seen that some computational methods are suitable for distinguishing between the regioisomers. The calculated 13C NMR spectra and optical rotations were close to the values found in literature and were sufficient in determining the difference between the two isomers. However, the calculated IR spectrum was an unreliable technique in distinguishing between X and Y due to the large errors in the higher frequency region and the similarities in the two spectra making them indistinguishable.

Overall Conclusions

The analyses shown above show that computational methods may be used to predict molecular energies and therefore may be used in a comparative fashion to predict reaction outcomes. This is unfortunately not the case when a reaction proceeds via a kinetic pathway (as shown for the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene). Molecular mechanics computational methods are sufficient for simple models, however MOPAC and Gaussian calculations provide a much more realistic picture due to their increased complexity, however this has the drawback of the calculations being highly time consuming as the size of the molecule increases. The Gaussian calculations may be used to predict spectra and this may be more widely used in the future for more complex molecules to support experimental data.

References and citations

- ↑ N. L. Allinger, U. Burkert, Molecular Mechanics, 1982 An American Chemical Society Publication

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S. Warren and P. Wothers in Organic Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 2008, ch. 45, p 1230

- ↑ L. A. Paquette, F. J. Montgomery, T. Wang, J. Org. Chem., 1995, 60, 7857–7864

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 P. M. Warner, Chem. Rev., 1989, 89, 1067-1093 DOI:10.1021/cr00095a007

- ↑ Anslyn and Dougherty, in Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, University Science Books, 2006

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12755

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12754

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 A. Heutling, F. Pohlki and S. Doye, Chem.--Eur. J., 2004, 10, 3059-3071 DOI:10.1002/chem.200305771

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12770

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12771

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12774

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12775

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12783

- ↑ P. Kenyon, H. Phillips and V. Pittman, J. Chem. Soc., 1935, 1072-1084 DOI:10.1039/JR9350001072

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-12781