Rep:Mod:El1612

The Cope Rearrangement - Tutorial

Abstract

Throughout this tutorial, various conformers of 1,5-hexadiene and the transition states of the cope rearrangement were studied. The structures were computed using the Hartree-Fock optimization model at the 3-21G basis set level of theory (Hartree-Fock is not an optimization model, it is the most standard ab initio method to calculate the energy of a polyelectronic system João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)). The data obtained was used to identify the symmetry of the conformers, to study their structure and to calculate their relative energies. The calculations were run anew using the Density Functional Theory, the B3LYP functional and the 6-31G* basis set and the results were compared. Finally, the information collected on the conformers and on the transition states was used to calculate the activation energy of the Cope rearrangement.

Introduction

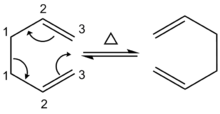

The reaction that will be examined in this section of the experiment is the Cope Rearrangement. This [3,3]-sigmatropic shift is portrayed in Figure 1. The reaction involves 6 electrons and thus satisfies the "4n+2" rule for n=1. It is thermally allowed via Hückel topology with suprafacial orbital components. For the purpose of this experiment, it will be assumed that the reaction is truly pericyclic and proceeds via a boat or a chair transition state. However, whether this reaction occurs in a concerted fashion or goes via a biradicaloid intermediate is a subject of controversy in the literature.[1],[2],[3] Recently, the bis-homo aromatic transition state of a semibullvalene derivate as been isolated, suggesting that some substituted 1,5-hexadiene species do undergo [3,3]-sigmatropic shifts via an aromatic transition state and are truly pericylic.[4]

Experimental Method, Results and Discussion

Optimisation of 1,5-hexadiene conformers using the Hartree-Fock theory

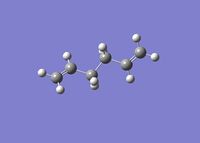

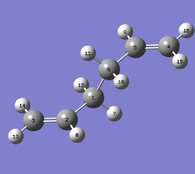

At the start of this experiment, GaussView 5.0.9 was used to draw the anti-periplanar conformer of 1,5-hexadiene. The structure was obtained from a cyclohexane framework by removing the C1-C6 bond and adding a double bond between the C1 and C2 and between the C5 and the C6 carbon atoms. The now superfluous hydrogens on the second and the fifth carbon had to be removed manually. Then, the dihedral angle between the four central carbon atoms was set to 180 degrees. Finally, the "clean" function was used to clean up the structure (See Figure 2).

The anti-periplanar 1,5-hexadiene species obtained in the previous step was then optimized using the Hartree-Fock theory at the 3-21G basis set level (HF/3-21G) and Gaussian 09W. The structure, the energy and the symmetry of the optimised molecule, conformer A, was computed. The Newman projection of A was created using Chemdraw Pro 14.0. This data is tabulated in Table 1.

The optimisation steps previously carried out were repeated starting with a gauche 1,5-hexadiene precursor. The precursor was formed by setting the dihedral angle between the four central carbon atoms to 60 degrees. The structure was "cleaned" using the clean function in the edit menu and then it was optimized using the HF/3-21G level of theory. The energy, the structure and symmetry of the computed molecule, conformer B, is tabulated in Table 1.

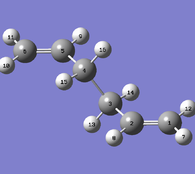

The bond angles, the dihedral angle and the inter-atomic distances in the two conformers was investigated. The bond angles m and n, shown in Figure 3, should ideally be 120° as the central atom is a sp2 carbon. Likewise, bond angle o should be 109.5° since this angle allows the four substituents to be as far apart as possible from each other whilst remaining bonded to the sp3 carbon centre. In both conformer A and B, the bond angles for m and n are distorted to 116° and 125° respectively. Angle o is obtuse in both A and B, 111° and 112° respectively. From this analysis, it is concluded that the distortion of the bond angles from ideality is not the reason why conformer B is higher in energy than conformer A.

The inter-atomic distances were then studied. The Van der Waals (V.D.W.) radii of hydrogen and carbon are 1.20 and 1.70 Å.[5]. For conformer A, the distances p and q are much bigger than two times the V.D.W. radii of hydrogen and carbon, which suggests that there are not interacting significantly. For conformer B, the C2---C5 inter-atomic distance is 3.08 Å (which is smaller than 2 x 1.70 = 3.40 Å). The lengthening of the double bonds in B compared to A indicates that the double bonds are delocalised to a small extent. This stabilises conformer B. Nevertheless, B is overall less stable and thus higher in energy than A because.

Therefore, it is hypothesis that the energy of the conformers is mostly determined the dihedral angle between the carbons highlighted in red and in blue in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the dihedral angle between the substituents of conformer A and B. Ideally it should be around 120° as it put the two alkene groups as far apart from each other as possible whilst maintaining the possibility for C2---C5 long range interactions. The calculated angle for conformer B is 109°. As shown in Figure 4, H/H and alkene/hydrogen steric clashes are found at this angle. The structure of conformer A is closer to the ideal staggered conformer, with a dihedral angle of 115°. This explains why A is lower in energy.

As a result, it can be concluded that the lowest energy conformer has the red and the blue carbons located at 120° from each other. Distance q should also favour delocalisation of the multiple bonds. Another conformer, conformer C, was sketched on GaussView with this information in mind and it was optimised as previously. The result of the HF-3-21G optimisation are listed in Table 1. Conformer C displays ideal bond angles of m and n = 120° and o = 109.5°. p is bigger than two time the V.D.W. radius of hydrogen and hence there is no significant H---H repulsive interactions. Moreover, q is 2.95 Å, which suggests some interaction between C2 and C5. Delocalisation of the double bonds is indicated by the significant lengthening of the double bonds. The trend in the lenght of the double bonds in conformer A to C goes as follow: A (C=C) : 1.3161 Å, B (C=C) : 1.3164 Å, B (C=C) : 1.3552 Å). The dihedral angle between C1 and C4 is 120° as shown in Figure 4.

Introduction to the Density Functional theory

Now, the HF/3-21G optimisation method that was employed so far will be compared with the Density Functional Theory (DFT) optimization theory using the Becke-3LYP method and the 6-31G* basis set(B3LYP/6-31G(d)). The latter level of theory as been used to determine the relative energies of the transition states as well as good estimates of the transition states geometry.[6] First, conformer D was computed using the HF/3-21G optimisation technique as in the previous steps. The results are tabulated in Table 1. It is noted that the energy of this conformer is higher than that of A and C, but lower than that of B. Looking at the dihedral angle between the first and the fourth carbon along the chain provides insight as to why this is. From Figure 4, we can easily understand the relative energies of A, C and D. However, the relative energy of B and D is less obvious. B is higher in energy than C because the conformer has a greater alkene-hydrogen steric clash, and thus a stronger C-H repulsive interaction. The latter interaction is more destabilising than H-H steric clashes and thus dominates here.

It is relevant to note that this interpretation of the relative energy level of the conformers is based on the results obtained using the HF/3-21G optimisation method. When the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory is applied, a different result is obtained as pictured in Figure 5. Indeed, the dihedral angles in conformer D become similar to those found in C. This stabilises the conformer and reduces its energy by about 1832 kcal/mol (It is not legitimate to compare absolute energies calculated at different methods of theory. One could compare relative energies however. João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)) . This rises a question: would the relative energy of the conformers be the same using the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory? This was investigated and tabulated in Table 2. It can be observed that the energy of conformer C is the only one that change significantly. The conformer C' obtained no longer has ideal dihedral angles and is destabilised which increases its relative energy. The opposite case is observed for conformer A', which becomes the most stable conformer.

| Conformer | Energy (in Hartrees;HF/3-21G) | Relative Energy (in kcal/mol) | Energy (in Hartrees;DFT B3LYP/6-31G*) | Relative Energy (in kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | -231.6926024 | 0.04 | -234.6117906 | 0.00 |

| B | -231.6915303 | 0.71 | -234.6106849 | 0.70 |

| C | -231.6926612 | 0.00 | -234.6113292 | 0.30 |

| D | -231.6925352 | 0.08 | -234.6117070 | 0.05 |

| Energy (in cm-1) | Corresponding vibration | Intensity |

|---|---|---|

| 939.9 | Methylene wagging motion | 70.6 (strong) |

| 1734 | Asymmetric C=C stretch | 18.1 (weak) |

| 3032 | Symmetric sp3 C-H stretch | 53.4 (medium) |

| 3081 | Asymmetric sp3 C-H stretch | 35.7 (medium) |

| 3137 | Symmetric sp2 C-H stretch | 56.2 (medium) |

| 3234 | Asymmetric sp2 C-H stretch | 45.5 (medium) |

Again, using the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* method, the frequencies in the IR spectrum of conformer D were computed. Figure 6 shows the spectrum. In Table 3, the major peaks are listed and assigned. As expected, the sp2 C-H stretches appear at a higher frequencies than the sp3 C-H stretches and they are found in the 3000-3250 cm-1 region. Asymmetric C-H stretching modes are found at higher frequencies and thus have a higher energy level than the equivalent symmetric stretching mode. This result is also in accordance with expectations. The symmetric C=C stretch is not seen in the spectrum of conformer D because this vibrational mode does not have a net dipole change. However, the asymmetric stretching frequency is noted as expected around 1735 cm-1. The strong peak found at 940 cm-1 arises from the synchronised wagging motion of the terminal methylene groups. This vibrational mode is shown below. It is noted that there is no imaginary stretching modes for this conformer, which suggests that conformer D is a real conformer of 1,5-hexadiene and not a transition state geometry.

Useful thermodynamic data can also be obtained from the previous computation. The sum of the electronic and the zero-point vibrational energy of conformer D or in other words its potential energy at absolute zero, was calculated to be -234.469213 in hartree/particle. This corresponds to -141 131 kcal/mol. At standard temperature and pressure (298.15 K and 1 atm), there is a vibrational, a rotational and a translational energy contribution to the total potential energy. The sum of the electronic and the thermal energy, Eelec, Evib, Erot and Etrans, was calculated to be -234.461865 hartree or -147 129 kcal/mol. The latter potential energy value was also computed using thermal enthalpies rather than thermal energy to account for RT, -234.460921 hartree or -147 127 kcal/mol. Note that RT increases the energy value, makes it less negative (H = E + RT). Finally, the potential energy value was computed anew and entropy was taken into account by the program. The free energy value obtained was -234.500788 hartree or -147 152 kcal/mol.

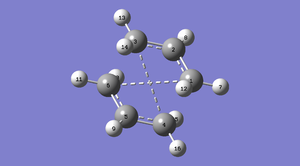

The chair and the boat transition states of the Cope Rearrangement

Using the HF/3-21G method previously described, a propene segment was optimised and duplicated (Does propene have the chemical formula of the fragment you want? João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)). The two segments were placed at approximately 2.2 Å of each other to form a guess chair transition state. The structure was optimised and its vibrational mode were computed using the HF/3-21G level of theory. Previously, conformers were optimised to a minimum energy, but in this case, the structure is optimised to a Berny transition state. The Hessian is set to be calculated at the beginning of the optimisation to indicate where the negative direction of curvature lies (i.e. the "calculate force constant" option in the Gaussian menu is set to "once") (You are actually suing a reduced Hessian, not the full matrix but only the components of the forming/breaking bonds João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)). It will then be updated automatically as the calculation proceeds. The "NoEigen" option is specified to ensure that the computation will not stop if the optimised structure has more than one imaginary vibrational frequency. This can occur if the guess transition state geometry is very inaccurate. In this case, the HF/3-21G optimised transition state obtained, transition state E, only had one imaginary frequency in its IR spectrum at -817.9 cm-1, suggesting that the geometry of the guess structure was good. The vibration giving rise to this peak is that of the cope rearrangement as shown in the figure below. The energy of E was -231.6193222 hartree or -145 343 kcal/mol. The chair transition state E is 2045 kcal/mol (Something is not right, this value seems too big João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)) higher in energy than the lowest energy 1,5-hexadiene conformer at the HF/3-21G level of theory, conformer C.

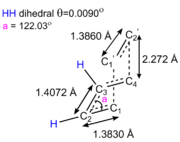

The previous step is carried out again, but this time a transition state precursor was first generated. The distance between the carbon atoms where the bonds are formed and broken was fixed to about 2.20 Å using the redundant coordinate editor and the transition state precursor was optimised to a minimum (rather than optimising straight away to a Berny transition state). The energy of this optimised transition precursor (F) is -231.6153223 hartree or -145 341 kcal/mol. A transition state was then optimised using F as a starting point. The force constant was be derived using a normal Hessian taking into account the position coordinates of the carbons pairs that were being differentiated (the carbon atoms at which the bonds are broken and formed). In order to do so, the "Calculate Force Constant" option was set to "Never" and the frozen bonds were unfrozen using the redundant coordinate editor. This transition state optimisation yielded a TS structure (G) with an energy of -231.6193223 hartree or -145 343 kcal/mol, which is only 13 x 10-8 hartree lower in energy than the structure obtained in the first transition state optimisation that was carried out. The IR spectrum of G shows the same imaginary infrared absorption as E at -817.9 cm-1. It corresponds to the Cope Rearrangement. The distances between C3-C4 and C1-C6 vary slightly between E and G, respectively about 2.0205 and 2.0207 Å. The distance between the carbon atoms on the propene like moiety which are not involved in the bond breaking/forming process is longer in E than in G, 2.8800 vs. 2.8790 Å. Both E and G have the correct chair TS C2h symmetry.[7]

In a second place, the structure and the energy of the boat transition state was investigated. First, conformer D was used as a framework for the product and the reactant molecules. The atoms in the molecules were then numbered to reflect their initial and their final arrangement as shown in Figure 7. Then, the HF theory and the 3-21G basis set were used to optimise to a QTS2 transition state. Instead of a boat, a chair-like transition structure is obtained. Its energy and the the distance between the allyl fragments fit the data previously calculated for TS E and G (Energy = -231.6193224 hartree). However, the bond are formed in a cross-linked fashion. This is shown in Figure 7. It can be observed that the QTS2 method simply broke the C3-C4 bond in the starting material and translated the allyl fragments obtained on top of one another. The method did not consider the possibility of rotating the fragments to form a boat transition state and thus we cannot obtain a boat TS as long as we use conformer D as a starting material (SM) and a product molecule (PM).

|

|

|

The next logical step was to design a SM and a PM from which the program could derive two allylic fragments that could be translated to give a boat transition state. D was thus modified by setting the dihedral angle between C2-C3-C4-C5 to 0°. Then, the angle between C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 was adjusted to 100°. These changes are mirrored in the PM. The HF/3-21G optimisation to a TS (QTS2) and attempted once again using these modified SM and PM. This time, a boat TS (H) was successfully computed with an energy -231.6028024 hartree a distance of 2.1398 Å between C3-C4 and C1-C6. The symmetry of the computed molecule matched that reported in the literature, C2v.[8] The pairs of carbon atoms involved in the bond breaking/forming during the cope rearrangement are further apart for the boat TS H than for the chair TS E and G but C2 and C5 are brought closer together in H (2.78 Å vs. about 2.88 Å). The imaginary stretching frequency found at -840.1 cm-1 in the IR spectrum of H corresponds to the cope rearrangement. The cope rearrangement imaginary vibrational mode is shown below:

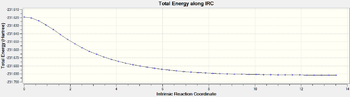

So far in this section, the geometry and the energy of the chair and the boat transition states has been computed. We will now investigate which hexadiene conformer the chair transition state decomposes into using E. This can't be determined simply by looking at the geometry of the transition states. The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method will allow us to investigate this. The method calculates the minimum energy path from the local maximum, the TS, to the local minimum, the product on a potential energy surface. Note that the computation is carried forwards only, from the saddle point of the potential energy surface, TS E, to the local minimum, the products, because the reaction is symmetrical. Hence, the products and the reactants have the same energy and conformation. The force constant will be calculated for each geometry steps as the calculation proceeds. First, the number of points along the IRC is set to 80. The conformer computed, conformer I, is reported to be one of the ten conformers of 1,5-hexadiene.[9] The energy of the product was -231.6915783 hartree and the conformer is found to have C2 symmetry. From the Energy versus IRC plot generated, it is hard to tell whether the conformer is at its true minimum energy (i.e a stationary point on the potential energy surface) (Couldn't you have confirmed this running a frequency calculation? João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)). To ensure that the product identified is a stationary point of the potential energy well, the calculation is carried out again and the number of points along the reaction coordinate is doubled. The same result is obtained and the gradient converges to zero, confirming that I is the conformer from which the chair transitions state E arises. However, the RMS gradient is not quite 0 thus I is optimised to a minimum using HF/3-21G to estimate the actual electronic energy of I at the true stationary point. As expected, a lower value is obtained for the energy of I. Its energy is found to be -231.6916670 hartree or -145 388.838 kcal/mol and its relative energy to conformer C is 0.62 kcal/mol. Figure 8 shows the IRC plot generated as well as pictorial representation of the changes in the C3-C4 and C1-C6 distance as product I is formed. Conformer I is also optimised to a minimum using the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* method and the results are tabulated in Table 4.

To continue, the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* higher level of theory gives different energies and slightly different geometries to conformers A to D. This means that different energies and geometries would be obtained if we were to re-optimise the chair and the boat transition states using the DFT theory, the B3LYP functional and the 6-31G* basis set. TS E is reoptimised first to a precursor for TS E". A good chair TS precursor is obtained with C2h symmetry and an energy of -234.5569308 hartree or -147 186.585 kcal/mol is generated. The cope rearrangement vibration is found at -569.4 cm-1. The C3-C4 and C1-C6 bond distances is 1.967 Å and the C2-C5 distance is 2.910 Å. The precursor is then optimised to a TS (Berny) (Not sure I understand what you are doing here, didn't you just re-optimize a transition state using DFT? You are doing it a second time? João (talk) 12:16, 26 December 2014 (UTC)). The force constant is calculated once. The opt=noeigen is specified to ensure that the computation reaches completion even if more than one imaginary frequency is obtained. TS E" is finally obtained and has an energy of -234.5569311 hartree, a C3-C4 and C1-C6 distance of 1.9668 Å and a C2-C5 interatomic distance of 2.9104 Å. One imaginary frequency corresponding to the cope rearrangement is obtained at -569.3 cm-1. This two step DFT transition state optimisation was repeated with TS H and yielded TS H". H" has an energy of -234.5430787 hartree, a C3-C4 and C1-C6 distance of 2.206-7 Å and a C2-C5 interatomic distance of 2.856 Å. One imaginary frequency corresponding to the cope rearrangement is obtained at - 532.2 cm-1.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (0 K) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (0 K) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | ||||

|

-231.619322 | -231.466699 | -231.461339 | -234.556931 | -234.414909 | -234.408980 | |||

|

-231.602802 | -231.450928 | -231.445299 | -234.543079 | -234.402360 | -234.396016 | |||

|

-231.691667 | -231.538704 | -231.531794 | -234.610703 | -234.468244 | -234.460957 | |||

Using the energy computed for the chair TS, the boat TS and SM/PM I, the activation energy for the reaction according to the two levels of theory can be calculated. The results of this calculation are displayed in Table 5. As expected, forming the boat transition state requires a greater energy than reaching the chair TS.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (0 K) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (0 K) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (298.15 K) | |

| ΔE Chair TS (kcal/mol) | 45.18 | 44.21 | 33.47 | 32.62 |

| ΔE Boat TS (kcal/mol) | 55.08 | 54.28 | 41.34 | 40.75 |

Conclusion

To conclude, the computations carried out in this section were successful in generating the boat and the chair transition state for the Cope [3,3] sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. The transition state geometries obtained matched that reported in the literature. The activation energies calculated using the energies computed at the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory was close to the literature values for the chair and the boat transition state 33.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol and 44.7 ± 2.0 kcal/mol respectively. The relative energy of the transition states that were generated was correct. [10] A limitation of this computational method used is that it does not consider solvent effects and intermolecular interaction, as it assumes that the molecule is isolated and behaves like a gas molecule. This is why the experimentally obtained energy values differ slightly from the computed activation energies even though the transition states computed are suitable.

The Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

Abstract

In this computational exercise, the transition states diels-alder cycloaddition was investigated. A simple cis-butadiene/ethylene diene/dienophile system was studied first at the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory on Gaussian 09W. The HOMO of the transition state was generated and characterised. The semi-empirical AM1 method was then used to compute the transition state structure of the [4+2] cycloaddition between maleic anhydride and 1,3-cylohexadiene. The endo- and the exo-transition state were generated and characterised. The relative energy of the endo- and exo-TS was justified.

Introduction

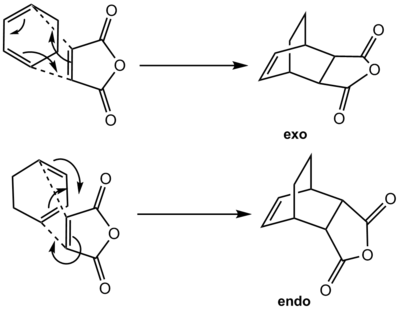

In the first part of this exercise, a straightforward diels-alder [4+2] cycloaddition was investigated using an unsubstituted diene/dienophile pair. The molecular orbitals of the transition state were visualised to provide insight on the reaction. Indeed, the transition should have both suprafacial components at the site of bond formation if it is an Hückel thermally allowed transition state for the diels-alder reaction. Looking at the imaginary frequency of the transition state and visualising the reaction path that it represents also allow to investigate the suitability of the transitions state structure computed. In the second part of this exercise, the effect of secondary overlap on the relative stability of the endo- and exo- transition states of the reaction between maleic anhydride and 1,3-cyclohexadiene will be investigated. Secondary orbital overlaps between a diene species and the maleic anhydride C=O π* orbital is reported to have a stabilising effect. [11] C=O π* is a good electron density acceptor as it is lower in energy than the C=C donor bond due to the electronegative oxygen. The reaction scheme for the formation of the endo and the exo-adduct is shown below:

Experimental, Results and Discussion

Ethylene and cis-Butadiene Cycloaddition

To begin with, cis-butadiene was optimised to a minimum using the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. A planar C2v molecule, J, was obtained with an anomalous imaginary frequency at -125.32 cm-1 (This is a very relevant fact that should have been documented better. Did you try to localize the local minimum? Why did you choose to proceed the study with this C2v structure if you found it to be unstable? João (talk) 00:42, 27 December 2014 (UTC)). This suggest that the cis-rotamer of butadiene is in fact a "transition state" and this is confirmed in the literature.[12]. The animation of the imaginary frequency shows that the dihedral angle between the hydrogen attach to C2 and C3 should be bigger than 0 degree (i.e. the molecule should not be planar). The bond angles and the bond lenght correspond to expected C=C double bonds and C-C single sigma bonds. The electronic energy of J is -155.985951 hartree or -97 882.362 kcal/mol. The sum of the zero-potential vibrational energy and the electronic energy of J (i.e. the energy at 0 K neglecting "RT" and entropic contribution) is -155.900839 hartree or -97 829.180 kcal/mol. The energy of J at 298.15 K is -155.896797 hartree or 97 826.643 kcal/mol.

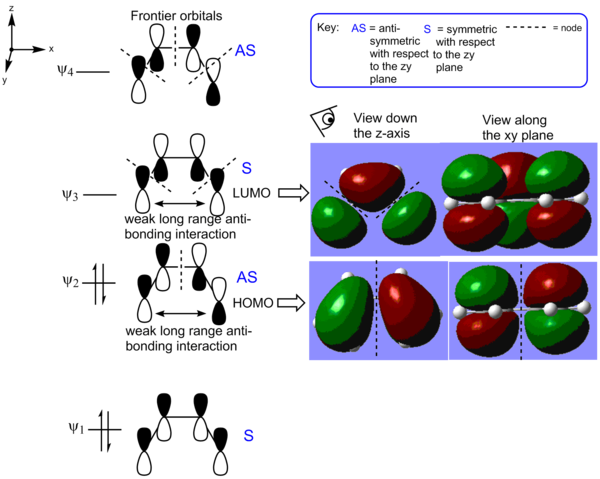

The optimisation that was just carried out will be useful when trying to compute the transition state of the diels-alder [4+2] cycloaddition of ethene and cis-butadiene. It is also relevant to use the data computed to observe the highest energy occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest energy unoccupied orbital of cis-butadiene (LUMO). The orbitals are showed in Figure 10. The HOMO has one nodal plane along the zy plane whereas the LUMO has two nodal planes as expected. The HOMO is slightly destabilised by a long-range antibonding interaction and the LUMO is stabilised by a weakly bonding long-range interaction. Overall, the number of antibonding interactions in the MOs through bonds dominate their relative energies.

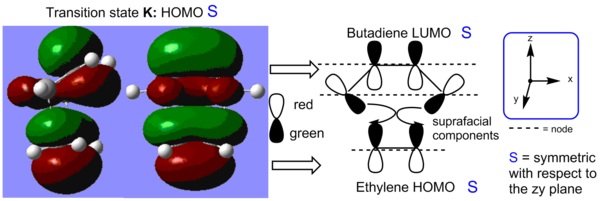

A bicyclo-[2.2.2]-octane molecule was use as a framework to produce a guess transition state for a B3LYP/6-31G* optimisation to a TS (Berny). The distance between the ethylene and the cis-butadiene fragment was set to 2.3 Å. This is shorter than two times the Van Der Waal's radius of carbon (i.e. 1.7 Å x 2 = 3.4 Å), but shorter than a carbon-carbon single bond (1.45 Å). The "NoEigen" option is used to ensure that the calculation will reach completion. An envelop shaped transition state is obtained, TS K, with a Cs and a plane of symmetry along through the z axis. The C1-C2 bond length is larger in the transition state than in the free cis-butadiene as a result of the delocalisation of the double bonds. On the opposite, the delocalisation of the three double bonds in the transition states yields a shorter C2-C3 bond as the latter increases in pi bonding character (How about the forming bonds? The bond length is less than twice the Van der Waals radius for carbon, is that relevant? João (talk) 00:42, 27 December 2014 (UTC)). The electronic energy of K is found to be -234.543886 hartree or -147 178.339 kcal/mol. Its energy at 0 K is -234.403329 or -147 090.197 kcal/mol and its energy at 298.15 K is -234.396908 hartree or 147 086.169 kcal/mol.

The imaginary frequency corresponding to the diels-alder cycloaddition is found at -526.8 cm-1. The vibration is synchronous as shown below. This makes sense as the diels-alder cycloaddition is a concerted π4s + π2s pericylic reaction. The asynchronous vibration, which does not lead to the formation of product, is seen at 136.1 cm-1.

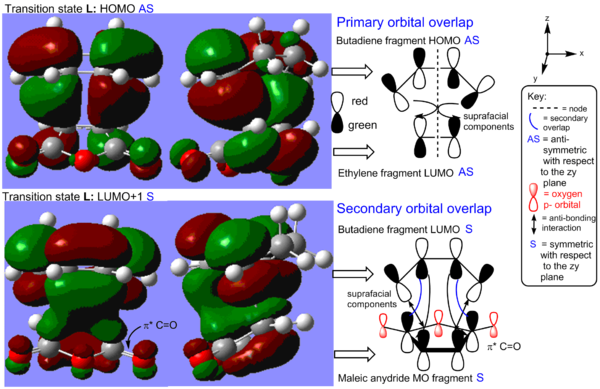

The HOMO orbital of the diels-alder transition state was then analysed. In Figure 13, the MO of the TS is broken down into ethylene and butadiene fragment orbitals. The transition state is formed with suprafacial components via disrotation. There are 3 nodal xy planes in the HOMO and the latter is symmetric with respect to the zy plane.

(What about the LUMO? According to Woodward-Hoffmann rules, why is the reaction allowed?</span João (talk) 00:42, 27 December 2014 (UTC))

1,3-Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride Cycloaddition

For an unsubstituted diene and dienophile pair, as in the previous section, there is only on possible transition state. In this section, we will study a diels-alder cycloaddition involving an asymmetrical dienophile, maleic anhydride and a locked cis-diene species, 1,3-cyclohexadiene. This diene-dienophile pair can undergo a diels-alder cycloaddition via an endo transition state, which benefits from less streric hindrance and secondary orbital overlaps or it can proceed via an exo structure, which offers poor secondary orbital overlap and . The two transition state decompose into the endo- and the exo-adduct respectively. The endo transition state structure will be analysed first. A guess transition state of structure is built on GaussView using K as a framework. The distance between the maleic anhydride and the 1,3-cyclohexatriene fragments is expanded to 3 Å form a pair of starting materials in one window. This lenght is chosen because it is shorter than two time the Van Der Waal's radius or carbon and longer than a sigma bond. Also, this distance is slightly above that in the TS structure reported for the endo-TS for the cylopentadiene analogue of this TS [13] In another window, a guess of the structure of the endo adduct is sketched and the distance between the diene and the dienophile is set to 1.5 Å, just above the length of a sigma bond. The adduct precursor is optimised to a minimum using the semi-empirical level of theory the AM1 method. The method omits some integrals in the calculations and replaces others by experimental data. This method will be used throughout this section as it allows for accurate results and makes the computations less time consuming.

The molecule obtained is shown is Figure 14. The adduct has Cs symmetry and an electronic energy of -0.16017075 hartree or -100.50859 kcal/mol. Its energy at 0 K is calculated to be 0.031464 hartree or 19.74394 kcal/mol and its energy at 298.15 K is 0.040462 hartree or 25.390 kcal/mol. No imaginary frequency is recorded showing that the molecule obtained is not a transition state. The C=C stretch is seen at 1814 cm-1 in the IR spectrum of the product and the C=O asynchronous stretch is found at 2096 cm-1.

Figure 14. The 1,3-cyclohexatriene maleic anhydride endo-adduct. |

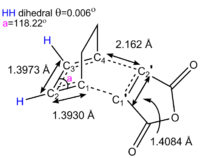

The starting material previously sketched and this optimised adduct are then used to find the transition state of the cycloaddition by optimizing the SM and the PM to a TS(QTS2) using the semi-empirical level of theory and the AM1 method. The geometry of the TS obtained is shown in Figure 15. As in the ethylene-butadiene TS, the delocalisation of electron cause the C1-C2 bond length to increase and the C2-C3 to decrease because of a decrease in bond order in the former and vice-versa. The same reasonning justifies the lengthening of the C1'-C2' bond of the dienophile. The dihedral angle shows that the diene is close to being fully planar. The TS has overall Cs symmetry and an electronic energy of -0.05150479 hartree or -32.31977. The thermochemistry calculations tell us that the TS has an energy of 0.133494 in hartree or 83.76869 kcal/mol at 0K and 0.143683 in hartree or 90.16194 kcal/mol at 298.15 K. The TS optimised is indeed the correct TS for the concerted diels-alder cycloaddition under investigation as confirmed by the imaginary frequency vibration at -806.4 cm-1. The latter is shown below The asynchronous diels-alders bond formation causes the vibration seen at 62.44 cm-1.

The cycloaddition leads to the formation of two single sigma bonds between the diene and the dienophile. These can be visualised in the HOMO of the transition state (see Figure 17). The HOMO is antisymmetric with respect to the zy plane. We can observe that the endo transition state is an early TS as it ressembles the structure of the starting material. This makes sense has the reaction is exothermic and thus the transition states energy also resembles that of the SM more than that of the products. What is interesting about this system, as oppose to the unsubstituted diene-dienophile complex studied previously, is that there is the possibility for secondary orbital overlap. This is observed in the LUMO+1 orbital of the endo transition state. The secondary overlap occurs between the carbonyl π* orbitals on the dienophile, which is localised on the less electronegative carbon atom, and the diene LUMO orbital. The C=O π* orbital is a low energy π acceptor orbital and has a suitable energy to interact strongly with the diene orbital. The geometry of the transition states also allows for a strong overlap. As before, the transition state MOs suggest that the bond formation process occurs with all suprafacial components via a disrotation, which is thermally allowed under Hückel theory for this 4n+2 system where n=1. The secondary orbital overlap also has all suprafacial components.

Below is another representation of the LUMO+1 and the HOMO of the endo-transition state that helps to visualise the MOs.

|

|

Now, the two step transition state optimisation is carried again for the exo-structure. The exo-adduct is optimised first and a molecule with Cs symmetry is generated. The adduct has an electronic energy of -0.15990940 hartree or -100.34459 kcal/mol and its energy at 0 K and at 298.15 K are respectively 0.031701 hartree or 19.896 kcal/mol and 0.040679 hartree or 25.5264 kcal/mol. The molecule has no imaginary frequency and shows the expected peaks for the C=C vibration at 1812 cm-1, for the C=O asynchronous vibration at 2096 cm-1 and for the C=0 synchronous stretch at 2173 cm-1 (although the latter is very weak in intensity due to the small magnitude of the dipole change during the vibration).

Figure 18. The 1,3-cyclohexatriene maleic anhydride exo-adduct. |

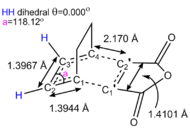

The exo TS was then computed as before using the semi-empirical level of theory and the AM1 method to obtain comparable data for the two transition state geometries. The C1-C2-C3 bond angle is reduced as the diene reacts with the dienophile and two of its sp2 centers and transformed into sp3 centers. The C1-C2 and the C3-C4 bonds of the diene as well as the C1'-C2' bond of the dienophile increase in magnitude as their π component is delocalised. This suggests that a TS was indeed obtained. The locked-cis diene species is planar in this TS according to the dihedral angle shown in Figure 19. The distance between the maleic anhydride segment and the 1,3-cyclohexadiene moiety is 2.170 Å. This is shorter than 2 times the VDW's radius of carbon but longer than a C-C sigma bond, which implies that something between a long range VDW's and a strong C-C bonding interaction is taking place. The distance between the -CH2-CH2- group from the 1,3-cyclohexadiene fragment and the maleic anhydride (O=C)-O-(C=O) group is about 2.9 Å (Should you not check the distance to the H atom instead? João (talk) 00:42, 27 December 2014 (UTC)). This repulsive interaction destabilises the exo-trantition state. In the endo transition state the distance between the maleic anhydride and the -CH=CH- fragment from the 1,3-cyclohexadiene moiety is shorter but MOs show that this interaction is favourable due to secondary orbital overlaps.

The transition state has a plane of symmetry and it belongs to the Cs point group. The exo-TS has an energy of -0.05041985 hartree or -31.48765 kcal/mol, which is 0.83 kcal/mol higher than the energy of the endo-TS. This explains why the reaction is kinetically controlled and thus favours the formation of the endo adduct. At 0K and 298.15 K, the energy of the exo-transition state is 0.134881 hartree (84.23440 kcal/mol) and 0.144882 hartree (90.91476 kcal/mol) respectively. The imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction path is found at -812.2 cm-1, which suggests that the correct exo-TS was identified. The synchronous vibration is shown below. The asynchronous vibration which cannot lead to the formation of product is seen at 60.84 cm-1.

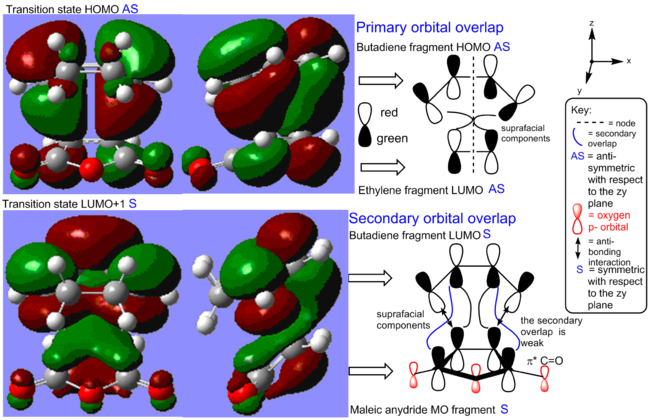

The molecular orbital of the exo-transition state are shown in Figure 20 and can be compared to those of the endo-transition state. Whilst the HOMO looks similar in both transition state, the LUMO+1 is significantly different. Indeed, in the exo transition state, the secondary overlap between the C=O π* orbital and the cis-diene is weak because of the geometry of the molecule. Indeed, the two interacting orbitals are far apart in the exo-transition state. On the opposite, a strong secondary orbital overlap is seen for the endo-transition state as the two interacting orbitals are brought closer together. This is thought to be the reason why the endo-transition state is more stable. Similar observations have been reported in the literature. For instance, the endo-TS of the cylopentaadiene analogue of this reaction has been reported to be 1.01 kcal/mol lower in energy than the exo-TS in the gas phase due to secondary orbital interaction. Interestingly, the reaction stereoselectivity was also found to be independent of solvent interaction.[14]

Below is another representation of the LUMO+1 and the HOMO of the exo-transition state that helps to visualise the MOs:

|

|

Conclusion

To conclude, the transition states of two diels-alder cycloaddition were studied. All three of transition states characterised showed a imaginary frequency which corresponded to the reaction path for the formation of the diels-alder adduct. This means that they were appropriate transition states for the latter reaction. Additionally, analysis of the molecular orbital showed that they were all formed by disrotation and that bond formation occurred with all suprafacial components. The π4s+π2s diels-alder cycloaddition going via the transition states computed were thus all Hückel thermally allowed reaction pathways. For the second part of this exercise, the stabilising effect of secondary orbital overlap was discussed. The endo-transition state was showed to have a lower energy than the exo-transition state by 0.83 kcal/mol, which is closed to the value reported in the literature for the cyclopentadiene analogue. Solvent effects were neglected for these computation, but it is reported in the literature that solvent effects have little impact on the stereoselectivity of the reaction.[15]

The endo- and the exo-1,3-cyclohexadiene maleic anhydride transition state were computed using the semi-empirical AM1 method. This method is less time-consuming than the DFT B3LYP/6-31G* method previoulsy used but it makes a lot of approximations. It omits some integrals of the Hamiltonian in the calculation and replaces a number of integrals with experimental data. For the reaction that was studied, this method provided accurate results. The results obtained computationally may not always be accurate as they assume that the molecules are isolated and in the gas phase and therefore neglects intermolecular interaction.

References

- ↑ M. J. S. Dewar, G. P. Ford, M. L. Mckee, H. S. Rzepa, and L. E. Wade, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1977, 5069.

- ↑ G. Klopman, A. J. Hopfinger, P. Andreozzi, and O. Kikuchi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1978, 100, 6268–6269.

- ↑ B. W. Gung, Z. Zhu, and R. A. Fouch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783.

- ↑ S. Zhang, J. Wei, M. Zhan, Q. Luo, C. Wang, W. Zhang, and Z. Xi, "2,6-Diazasemibullvalenes: Synthesis, Structural Characterization, Reaction Chemistry, and Theoretical Analysis", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 134, pp. 11964-11967, 2012.

- ↑ Bondi, A. J. Phys. Chem, 1964, 68, (3), 441.

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, and K. N. Houk, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116, 10336–10337.

- ↑ K. J. Shea, R. B. Phillips, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1980, 109, 3156.

- ↑ K. J. Shea, R. B. Phillips, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1980, 109, 3156.

- ↑ B. W. Gung, Z. Zhu, and R. A. Fouch, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783–1788.

- ↑ K. J. Shea, R. B. Phillips, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1980, 109, 3156.

- ↑ A. Arietta, F. P. Cossio, J. Org. Chem. 2001,66, 6178-6180.

- ↑ D. Feller, N. C. Craig, J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 1601–1607

- ↑ A. Arietta, F. P. Cossio, J. Org. Chem. 2001,66, 6178-6180.

- ↑ A. Arietta, F. P. Cossio, J. Org. Chem. 2001,66, 6178-6180.

- ↑ A. Arietta, F. P. Cossio, J. Org. Chem. 2001,66, 6178-6180.