Rep:Mod:ELM

Experiment 1C: Synthesis and Computational Lab

Objectives

To use computational techniques to model organic structures and their reactivity. During this report, modelling was used to rationalise the outcomes of reactions and predict properties of molecules.

Part 1

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

The Dimerisation and Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene is a small hydrocarbon with many interesting applications and in its deprotonated form is used in popular organometallic complexes such as ferrocene as the cyclopentadienyl ligand [1]. At room temperature, cyclopentadiene dimerises via a Diels-Alder cycloaddition, with the exo or endo dimer being formed [2]. It is possible to study the relative energies of the exo and endo dimers using computational molecular dynamics. In this case the MMFF94s force field option was used with the program Avogadro. Table 1 shows that in fact the exo dimer (Molecule 1) is lower in energy with the main difference being due to the angle bending. This could be from the bending inwards being less in the exo adduct, due to steric clashes with the bridgehead, than the outwards bending of the endo adduct. Commercial dicyclopentadiene is sold as >95 % endo dimer [3]. This means that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is under kinetic control, with the endo product (Molecule 2) being formed via the lower transition state. It was first proposed by Alder himself [4] and then later by Woodward and Hoffman [5] that the endo transition state is lower in energy due to more favourable orbital overlap between the respective HOMOs and LUMOs of the cyclopentadiene monomers.

Hydrogenated versions of Molecule 2, the endo adduct, were investigated in a similar manner using Avogadro and the results can also be seen in Table 1. Obviously Molecule 4 has a lower energy and this is mainly due to a lower bending energy. This could be due to the double bond in the five-membered ring having bond angles closer to an ideal sp2 hybridised 120o. This is in agreement with the literature [6], which states Molecule 4 is the formed product. Therefore it can be concluded that the hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene is under thermodynamic control since the most stable (thermodynamic product) is formed. The hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene is important for the synthesis of an organic intermediate adamantine, which is used in jet-fuel [7].

All values shown in Table 1 are reported in kcalmol -1 and rounded to 3 decimal places.

| Molecule | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bond stretching energy | 3.544 | 3.467 | 3.306 | 2.823 |

| Total angle bending energy | 30.773 | 33.191 | 30.851 | 24.686 |

| Total stretch bending energy | -2.041 | -2.041 | -1.926 | -1.589 |

| Total torsional energy | -2.731 | -2.950 | 0.080 | -0.378 |

| Total VdW energy | 12.851 | 12.357 | 12.722 | 10.637 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 13.014 | 14.184 | 5.121 | 5.147 |

| Total energy | 55.373 | 58.191 | 50.170 | 41.258 |

References:

- ↑ P. Atkins , T. Overton , J. Rourke , M. Weller and F. Armstrong, "Shriver & Atkins' Inorganic Chemistry ", OUP, 2010, 5th edition, 550

- ↑ A. G. Turnball and H. S. Hull, "A thermodynamic study of the dimerization of cyclopentadiene", Aust. J. Chem., 1996, 21, 1789-97

- ↑ J. D. Rule and J. S. Moore, "ROMP Reactivity of endo- and exo-Dicyclopentadiene", Macromolecules, 2002, 35, 7878-7882 DOI:10.1021/ma0209489

- ↑ K. Alder and G. Stein, Angew. Chem, 1937, 50, 510

- ↑ R. Hoffmann and R. B. Woodward, "Conservation of orbital symmetry", Acc. Chem. Res., 1968, 1, 17-22

- ↑ W. F. Maier and P. von Rague Shleyer, "Evaluation and Prediction of the Stability of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891-1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ G. Liu , Z. Mi , L. Wang , X. Zhang and S. Zhang, "Hydrogenation of dicyclopentadiene into endo-Tetrahydrodicyclopentadiene in Trickle-Bed Reactor: Experiments and Modeling", Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2006, 45, 8807-8814 DOI:10.1021/ie060660y

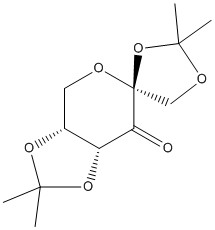

Atropisomerism refers to the phenomenon where stereoisomers are formed due to restricted rotation around a bond. In this case an intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol was investigated. Taxol is an anti-cancer drug given to many women for the treatment of breast and ovarian cancer and its effectiveness is thought to come from its role as a promoter of microtuble assembly [1]. In this intermediate, seen in Figure 1, the two different atropisomers come from the carbonyl either pointing up or down. The MMFF94s calculation was applied to both atropisomers in order to determine which isomer was most stable. In the next stage of Taxol synthesis the alkene is functionalised however this is observed to occur slowly [1]. By using molecular mechanics it was possible to explain this phenomenon.

Each isomer, Molecule 5 and 6, contain a cyclohexane motif, which can exist in a number of conformations. For the intermediate studied two chair conformations and two twist-boat conformations per isomer were studied. The twist boat-conformations can be excluded immediately since they are known to be much higher in energy [2]. The results of the force field calculations are recorded in Table 2, with all energies recorded in kcalmol-1.

| Molecule | 5a | 5b | 6a | 6b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bond stretching energy | 8.146 | 8.801 | 7.140 | 7.734 |

| Total angle bending energy | 32.242 | 33.510 | 22.442 | 19.625 |

| Total torsional energy | -0.363 | 3.151 | -1.906 | 3.244 |

| Total VdW energy | 35.378 | 36.025 | 32.107 | 34.973 |

| Total electrostatic energy | 0.445 | 0.238 | 0.830 | -0.046 |

| Total energy | 76.471 | 83.252 | 61.036 | 66.325 |

From this table it can be seen that Molecule 6 is more stable with one chair conformation being more favoured. This can be concluded since it is the atropisomer with the lowest total energy. The main difference in energy comes from the total angle bending energy, which suggests that when the carbonyl group is pointing down the bond angles around the sp2 C are more favourable. The bond angles around this sp2 C were calculated using Avogadro and indeed it was seen that Molecule 6a had a bond angle of 120.9 o versus 118.1 o for Molecule 5a. There is also less steric clash between the bridge-head and oxygen when the carbonyl group is pointing down.

Similar bridgehead olefins have been studied [3] and show an unexpected stability compared to their parent alkanes. This is thought to be due to less strain shown with a double bond next to the bridge compared to a single bond in large rings. For smaller rings the opposite effect is seen and a double bond adjacent to a bridge is very reactive. Since in this case the ring is 10-membered it is understood that hyperstability is in effect and so the double bond reacts slowly in the next stage of Taxol synthesis [4].

References:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 D. G. I. Kingston , G. Samaranayake and C. A. Ivey, "The Chemistry of Taxol, a clinically useful anti-cancer agent", Journal of Natural Products, 1990, 53, 1-12

- ↑ H. M. Pickett and H. L. Strauss, "Conformation, Structure, Energy and Inversion Rates of Cyclohexane and some related Oxanes", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1970, 92, 7281-7290DOI:10.1021/ja00728a009

- ↑ A. B. McEwen and P. von Rague Schleyer, "Hyperstable Olefins: Further Calculational Explorations and Predictions", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1986, 108, 3951-3960DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016

- ↑ W. F. Maier and P. von Rague Shleyer, "Evaluation and Prediction of the Stability of Bridgehead Olefins", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891-1900 DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

In recent years, computational methods have been able to predict NMR spectra of organic compounds by applying quantum mechanics in the GIAO approach[1]. In this part of the study, the aim was to predict the 1H and 13C NMR of another intermediate (Molecule 7) in the synthesis of Taxol[2], seen in Figure 2. It is a derivative of the more stable atropisomer previously seen as . Instead of focusing on the other atropisomer of Molecule 7 it was decided to investigate two different conformers; one chair and one boat of the cyclohexane ring present. The energies of both conformers were optimised in the same fashion as before and then entered in to the HPC supercomputer to obtain a NMR output file, which was viewed in Gaussview 5.0. The computed NMR spectra were compared with literature, in order to determine which conformer is preferred.

All values in Tables 3 and 4 are recorded in ppm and in Table 3 all peaks have an integration of 1H unless specifically stated otherwise.

| Literature [3] | Boat Conformation | Chair Conformation |

|---|---|---|

| 5.21 (m, 1H) | 5.33 | 6.23 |

| 3.00 - 2.70 (m, 6H) | 3.35 | 3.30 |

| 2.70-2.35 (m, 4H) | 3.20 (2H) | 3.22 |

| 2.20-1.7 (m, 6H) | 3.08 (3H) | 3.15 |

| 1.58 (t, 1H) | 2.96 | 3.03 |

| 1.50-1.20 (m, 3H) | 2.87 | 2.97 |

| 1.10 (s, 3H) | 2.59 | 2.84 (2H) |

| 1.07 (s, 3H) | 2.53 | 2.52 (2H) |

| 1.03 (s, 3H) | 2.35 | 2.28 |

| 2.08 (2H) | 2.08 | |

| 1.90 (2H) | 1.96 (2H) | |

| 1.78 | 1.81 (2H) | |

| 1.65 (2H) | 1.69 | |

| 1.57 | 1.60 (3H) (avg.) | |

| 1.56 (3H) (avg.) | 1.51 (3H) (avg.) | |

| 1.45 (3H) (avg.) | 1.42 | |

| 1.11 (3H) (avg.) | 1.22 (3H) (avg.) | |

| 1.06 | 1.13 (3H) |

Unfortunately it is difficult to compare every single literature peak with the computed proton NMR spectra. This is mainly due to the discrepancy between multiplets, which are well defined in the literature[3]. This was partly addressed by looking at the Gaussview output file and finding the proton number label for each hydrogen in a methyl environment. The proton NMR peaks for the identified hydrogens were then averaged to get a single value for each of the three methyl environments in each conformation and are marked with (avg.) in Table 3. However there is still a significant contrast between the literature values and the computed ones, including the difference of chemical shifts for each methyl environment, whereas in the literature all three show a similarity in value[3]. It is possible to analyse particular peaks with known assignment. For example, a large difference can be seen for the single alkene proton, which is seen at 5.21 ppm in the literature[3]. The boat conformation is much closer to the literature value whereas the chair conformation shows a much greater deal of deshielding. This may suggest that the calculated boat conformation is closer to the actual structure of Molecule 7.

| Literature [3] | Boat Conformation | Chair Conformation |

|---|---|---|

| 211.49 | 217.31 | 209.76 |

| 148.72 | 143.49 | 151.45 |

| 120.90 | 125.67 | 123.91 |

| 74.61 | 89.32 | 91.53 |

| 60.53 | 62.44 | 62.06 |

| 51.30 | 56.30 | 58.47 |

| 50.94 | 52.26 | 53.84 |

| 45.53 | 49.77 | 49.84 |

| 43.28 | 48.29 | 46.30 |

| 40.82 | 45.80 | 41.72 |

| 38.73 | 44.92 | 39.94 |

| 36.78 | 41.61 | 39.16 |

| 35.47 | 36.46 | 35.31 |

| 30.84 | 34.92 | 32.66 |

| 30.00 | 29.33 | 30.42 |

| 25.56 | 28.85 | 27.70 |

| 25.35 | 26.54 | 25.71 |

| 22.21 | 26.54 | 25.25 |

| 21.39 | 25.62 | 23.11 |

| 19.83 | 21.19 | 22.27 |

For the most part it is easier to compare the calculated peaks with the literature for the 13C NMR. Overall, there is good agreement with the literature[3] and not much difference between the boat and chair conformation values. This is understandable when considering that a change in conformation has a greater effect on the protons within the cyclohexane compared to the carbons themselves. Therefore there is a higher level of discrepancy between the conformers in the proton NMR compared to the carbon one. Using computational methods such as the ones described above could be used to compare the chemical shifts of cyclohexane conformers, considering it is so difficult to isolate conformationally pure samples, especially higher energy conformers such as the boat and twist-boat. The similarity in calculated values between the boat and chair conformations also make it difficult to determine which conformer is preferred or closer to reality. There are a few peaks in Table 4 that have a difference of over 5 ppm to the literature[3]. The large discrepancy for the peak at 74.61 ppm (in the literature), which corresponds to the carbon directly attached to the two sulphur atoms, probably arises from a spin-orbit coupling error due to the sulphur atoms being heavier and could be corrected.

The following analysis shows that calculated NMR spectra, seen below, using the above programs cannot be used alone to determine the accuracy of experimental NMR since both the computed 1H and 13C NMR show marked differences from what is expected.

|

|

|

|

The same HCP calculation was also used to find the sum of thermal and electronic free energies or the Gibbs free energy of the two different conformers. Originally the Gibbs free energy was given in Hartrees per particle, which was converted to kJmol-1 using a conversion factor of 2625.5 [4]. Table 5 shows that indeed the boat conformation is slightly more thermodynamically stable compared to the chair conformation.

| Boat conformation | Chair conformation |

|---|---|

| 4335884.60 | 4335910.85 |

- ↑ S. D. Rychnovsky,Org. Lett., 2006, 13, 2895-2898. DOI:10.1021/ol0611346

- ↑ D. G. I. Kingston , G. Samaranayake and C. A. Ivey, "The Chemistry of Taxol, a clinically useful anti-cancer agent", Journal of Natural Products, 1990, 53, 1-12

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ See http://web.utk.edu/~rcompton/constants

Part 2: Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

The oxidation of alkenes by asymmetric epoxidation can be achieved with a variety of catalysts [1]. In this study two catalyts, Shi and Jacobsen, were investigated because the former shows a preference for trans-alkenes [2] whereas the latter tends to react with cis-alkenes [3]. The aim was to predict the absolute configuration of the epoxide products using a variety of computational techniques. The alkenes, styrene and trans-stilbene, chosen to investigate were also synthesised in the 3rd year laboratory so some comparisons between experimental and computational values could be compared.

References:

- ↑ J. Clayden , N. Greeves , S. Warren and P. Wothers, "Organic Chemistry ", OUP, 2001, 1st edition, 1240

- ↑ Z. Whang, Y. Tu , M. Frohn , J. R. Zhang and Y. Shi, "An efficient catalytic asymmetric epoxidation model", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1997, 119, 11224-11235

- ↑ W. Zhang , J. L. Loebach , S. R. Wilson and E. N. Jacobsen, "Enantioselective epoxidation of unfuntionalised olefins catalyzed by (Salen)manganese complexes", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 2801-2803.

Crystal Structure of both Catalysts

To begin with the Conquest program was used to search the Cambridge Crystal Database for the crystal structure of a precursor to the Shi catalyst, seen in Figure 3. This provided a code, NELQEA, which was entered into the Mercury program to allow detailed analysis of the bond lengths in the anomeric centres (O-C-O combination). These are of particular interest since due to the anomeric effect a variety of C-O bond lengths were observed, which can be seen . The six-membered ring should prefer the α-anomer, with the ring oxygen sitting in an axial position. However, in Molecule 8 it is clear that in fact the donating anomeric oxygen is in fact the one shown in purple. The oxygen lone pair can donate into the C-X σ* orbital, which in this case is a C-O bond found in an anti-periplanar position in the same ring adjacent to this donating oxygen. This receptor (σ*) orbital leads to an increase, to 1.443 Å compared to the usual 1.43 Å, in the C-O bond length since an antibonding orbital is being populated. This second oxygen can then donate into the six-membered ring with appropriate bond lengths observed to confirm this. The C-O bond lengths in the other five-membered ring present show no deviation from normality since they are not in the correct conformation for correct orbital overlap to encourage donation.

When considering why Shi's catalyst reacts only with trans-alkenes it is important to know that epoxidation takes place at the dioxirane [1], which occupies a similar space to the carbonyl present. Also both five-membered rings are positioned at 90o to one another. Therefore a cis-alkene would encounter a great deal of steric hindrance on approach to the dioxirane. Trans-alkenes on the other hand would have a less-hindered approach and are therefore favoured upon reaction with Shi's catalyst.

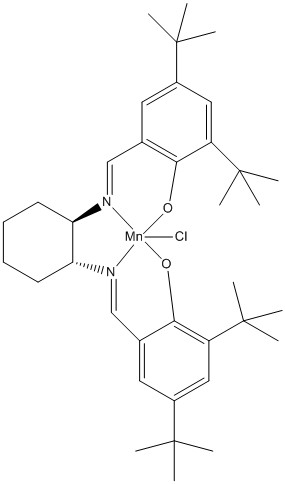

A similar investigation was carried out on a precursor to Jacobsen's catalyst, seen in Figure 4. However, on this occasion the code received from Conquest was TOVNIB and instead of looking at bond lengths the interspacial distance between two approaching atoms within the same molecule were studied. The chosen distance was between two tert-butyl groups on separate benzene rings. This distance was found to be 2.421 Å, seen . Since this is quite small it was concluded that the alkene must approach the Mn centre from either above or below the plane of the molecule. A cis-alkene can have both substituents pointing in the same way or in this case away from the bulky tert-butyl groups therefore making approach much less disfavoured compared to a trans-alkene.

References:

- ↑ Z. Whang, Y. Tu , M. Frohn , J. R. Zhang and Y. Shi, "An efficient catalytic asymmetric epoxidation model", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1997, 119, 11224-11235

Calculated NMR Properties of chosen two alkene epoxides

Although the final aim of this study was to find the absolute configuration of the epoxide products, it was valuable to calculate their 1H and 13C NMR spectra not only to optimise the geometry but also to compare to the results obtained in the laboratory. The same techniques were used as described earlier in Spectroscopic simulation using quantum mechanics to obtain the calculated NMR values seen in Tables 6 and 7, with all values recorded in ppm. The solvent chosen was deuterated chloroform.

| 1H NMR Literature [1] | 1H NMR Calculated [2] | 13C NMR Literature [1] | 13C NMR Calculated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.26-7.37 (m, 5H) | 7.49 (4H) | 137.6 | 135.54 |

| 3.87 (dd, 1H) | 7.30 | 128.4 | 124.13 |

| 3.15 (dd, 1H) | 3.66 | 128.2 | 123.41 |

| 2.81 (dd, 1H) | 3.12 | 125.2 | 122.96 |

| 2.533 | 52.4 | 122.95 | |

| 51.2 | 54.06 | ||

| 53.47 |

It is obvious that two chiral enantiomers are available for each alkene epoxide however on repeating the same calculation on each of the enantiomers it was found that identical NMR data was obtained therefore only one has been recorded. The calculated 1H NMR values show mostly good agreement with the chosen literature with the only discrepancy being due to the computational method recognising a separate peak at 7.30 ppm, when it should really be part of the five hydrogen multiplet due to the aromatic protons. There is similarity also in the 13C NMR of styrene oxide, also known as phenylethylene oxide [1] between the calculated and experimental literature values. The only marked difference is in the number of peaks recorded. The computational method has recorded more aromatic carbon peaks whereas in the literature, using experimental techniques, several of the aromatic carbons would be treated as chemically equivalent and therefore only one peak is observed. However the chemical shifts are all within five ppm of the literature. This high level of similarity in both nuclei NMR spectra suggests that the correct geometry of the epoxide was calculated and can therefore be used in further calculations to obtain the absolute configuration.

| 1H NMR Literature[3] | 1H NMR Calculated [4] | 13C NMR Literature[3] | 13C NMR Calculated |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.18 (s, 10H) | 7.57 (2H) | 134.5 | 134.09 |

| 4.37 (2H) | 7.48 (8H) | 127.9 | 124.22 |

| 3.54 (2H) | 127.6 | 123.52 | |

| 127.0 | 123.21 | ||

| 59.88 | 123.08 | ||

| 118.26 | |||

| 66.43 |

A similar analysis was carried out using trans-stilbene oxide. The 1H NMR shows very good agreement with a discrepancy only in that not all 10 aromatic hydrogens were calculated with the same chemical shift using the computational method. The 13C NMR does not show as good agreement as would be desired due to some peaks having more than a five ppm difference with the literature values. However on further investigation, other literature references were found that showed better agreement [5]. This shows not only that the correct geometry and optimisation was found for this particular epoxide but also that computational methods can be used to verify the accuracy of NMR spectra produced experimentally.

References:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 H. Toda , R. Tmae and N. Itoh, "Efficient biocatalysis for the production of enantiopure (S)-epoxides using a styrene monooxygenase (SMO) and Leifsona alcohol dehydrogenase (LSAPH) system", Tetrahedron. Asymmetry., 2012, 23, 1542-1549

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 E. Martenson, Styrene epoxide down, D-space DOI:10042/27531

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 M. Imuta and H. Ziffer, "Synthesis and Physical Properties of a series of optically active substituted trans-stilbene oxides", J. Org. Chem., 1979, 44, 2505

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 E. Martenson, Trans-stilbene epoxide nmr, D-space DOI:10042/27532

- ↑ Robert W. Murray and Megh Singh, Organic Syntheses, Coll. Vol. 9, p.288 (1998), Vol. 74, p.91 (1997)

Assigning absolute configuration of alkene epoxides

Calculated chiroptical properties of alkene epoxides

It was possible to calculate the optical rotation of each of the alkene epoxides by taking the NMR calculation output from the previous section and putting it into the HPC supercomputer. It was chosen to obtain the optical rotation at 589 nm. It is obvious that each alkene epoxide product has two chiral enantiomers and it was chosen to run the (R) and (R,R) series of styrene oxide and trans-stilbene oxide respectively. Their optical enantiomers would give the same optical rotation as reported but with the reverse sign. The calculated optical rotation of (R)-styrene oxide was -25.79o [1], which compares well with the literature value of -25.1o[2]. Similarly for (R,R)-trans-stilbene the computational method optical rotation was found to be 298.40o, whereas it has been reported in literature to be 310o [3]. The calculated optical rotation values are similar to the literature values given, however a large spread of reported peaks can be seen in other literature references [4] [5] [6]. Optical rotation calculations are highly sensitive to conformational changes, which could explain the variety in experimental literature values. Therefore computational methods could be used to get an accurate optical rotation for simple organic molecules.

References:

- ↑ E. Martenson, optical rotation of styrene oxide DOI:10042/27533

- ↑ H. Toda , R. Tmae and N. Itoh, "Efficient biocatalysis for the production of enantiopure (S)-epoxides using a styrene monooxygenase (SMO) and Leifsona alcohol dehydrogenase (LSAPH) system", Tetrahedron. Asymmetry., 2012, 23, 1542-1549

- ↑ M. Imuta and H. Ziffer, "Synthesis and Physical Properties of a series of optically active substituted trans-stilbene oxides", J. Org. Chem., 1979, 44, 2505

- ↑ A. Solladie-Cavallo and A. Drep-Vohuule, "A two-step asymmetric synthesis of pure trans-(R,R)-diaryl-epoxides", Tetrahedron. Asymmetry., 1996, 7, 1783-1788

- ↑ O. A. Wong , B. Wang , M. X. Zhao and Y.Shi, "Asymmetric epoxidation catalysed by a,a-dimethylmorpholinone ketone. Methyl group effect on spiro and planar transition states", J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 6335-6338

- ↑ D. J. Fox , D. S. Pedersen , A. B. Petersen and S. Warren, "Diphenylphosphinoyl chloride as a chlorinating agent - the selective double activation of 1,2-diols", Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006, 4, 3117-3119

Using the calculated transition states of alkene epoxides

The aim of this section was to find the absolute configuration of the alkene epoxide products by looking at enantiomeric ratios and energy differences in the transition state complexes with the respective Shi and Jacobsen catalysts.

Shi catalyst and trans-stilbene

Using provided log output files from the HPC, eight configurations of Shi's catalyst and trans-stilbene transition states were analysed to determine the lowest free energy of each enantiomer; (R,R) and (S,S). The eight potential configurations consisted of four (R,R)-series transition states and four (S,S) ones. The lowest free energy (R,R)-series transition state was recorded at -4029321.38 kJmol-1 [1], whereas the (S,S)-series transition state gave -4029311.37 kJmol-1 [2]. By getting the difference between these two values and entering them into the equation , where the difference between the free energies ((R,R) -(S,S)) was used for delta G, to obtain K, which refers to the equilibrium constant of the transition between enantiomers. R is the gas constant and was taken as 8.314 JK-1mol-1 and the temperature as 298.15 K, also known as the standard temperature. The enantiomeric excess was then calculated by taking the K (56.66), also known as the concentration of (R,R)-enantiomer, to show that (R,R)-trans-stilbene oxide is 96.56 % favoured over the equivalent (S,S)-enantiomer. This was achieved using the enantiomeric excess equation . The eight separate configurations come from a variety of choices made during the approach of the alkene towards the Shi catalyst, including endo versus exo approach and which dioxirane oxygen reacts [3].

Jacobsen catalyst and styrene

A similar investigation was carried out using different configurations of the transition state of Jacobsen's catalyst and styrene. The lowest free energy of the (R)-series was found to be -8779569.32 kJmol-1 [4] and -8779575.36 kJmol-1 [5] for the (S)-series. K was then found to equal 11.44, which gives a (R)-styrene oxide enantiomeric excess of 83.96 % over the (S)-enantiomer. This is a smaller excess compared to the Shi and trans-stilbene investigation since K, the equilibrium constant, is smaller. In conclusion, it was found that for the reaction of Shi's catalyst and trans-stilbene the (R,R)-epoxide would be expected and for the reaction of Jacobsen's catalyst and styrene the (R)-styrene oxide is in enantiomeric excess.

References:

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C26H30O7 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.830388

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C26H30O7 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.829524

- ↑ Z. Whang, Y. Tu , M. Frohn , J. R. Zhang and Y. Shi, "An efficient catalytic asymmetric epoxidation model", J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1997, 119, 11224-11235

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C36H44ClMnN2O3 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.860446

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C36H44ClMnN2O3 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.860445

Investigating the non-covalent interactions in the reaction transition state

To better understand the transition state of a successful reaction, non-covalent as well as covalent interactions have to be considered. The (R,R)-trans-stilbene oxide and Shi's catalyst transition state with the lowest free energy was chosen [1], as discovered in the previous section, to undergo a NCI (non-covalent interactions) analysis using the Gaussview program. The output can be seen below with areas of attractive electron density shown in green. A few repulsive areas, shown in red, are present in the five-membered rings and may be due to repulsion between the oxygen lone pairs. The darker the green colour the stronger the interaction. The darkest areas tend to be between two hydrogens and could refer to favourable Van der Waals interactions. Most of the interactions shown are individually weak however since there are many attractive interactions all around the molecule the effect will be cumulative and lead to a successful reaction as proved in the 3rd year laboratory. There is also a full ring of interactions seen below. It shows a multitude of colours and represents where the bond is formed during the transition state. Since this is actually a covalent interaction it was not analysed.

Orbital |

References:

- ↑ H. S. Rzepa (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C26H30O7 DOI:10.6084/m9.figshare.830388

Investigating the electronic topology (QTAIM) of reaction transition state

To obtain more information about the bonds forming in a transition state including the bond critical points (BCPs), the electronic topology of the transition state must be investigated. The same lowest free energy transition state of Shi's catalyst and trans-stilbene was analysed using the Avogadro2 program. The results can be seen in Figure 5, where the yellow spots refer to the BCPs and dotted lines represent weaker interactions, not full bonds. It can be seen that one of the alkene carbons looks to be bonding first to the dioxirane of the catalyst with the other carbon not involved, which suggests a non-concerted mechanism. This also changes the electron density of the C=C bond since the BCP is seen closer to the carbon interacting with the catalyst's oxygen. This could be due to the electronegative nature of the oxygen that this carbon is starting to bond with. Some weaker hydrogen-bonding interactions can also be seen in Figure 5 with the BCP sitting closer to the oxygen, due to its relative electronegativity.

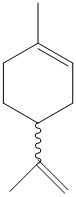

New candidate for investigation

For the final part of this study a new alkene was identified that could undergo a similar asymmetric epoxidation. Limonene, seen in Figure 6, is used in many industries, including the food industry [1]. There are two alkene functions in this particular molecule so an interesting aspect to investigate could be to see which alkene is most likely to be oxidised in the presence of Jacobsen and Shi catalysts. Another interesting point is that both (R)-limonene and (S)-limonene are available from sigma aldrich so experimental results could be compared. The experimental recorded optical rotation for (R)-limonene is 121 o at 589 nm [2] .

References:

- ↑ N. Garti , A. Yaghmur , M. E. Leser , V. Clement and H. J. Watzke, "Improved Oil solubilization in oil/water food grade microemulsions in the presence of polyols and ethanol", Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2001, 49, 2552–2562

- ↑ F. W. Hefenhehl "Beitrage zur biogenese atherischer ole", Planta Medica, 1979, 22, 378-380