Rep:Mod:ECN1911

Synthesis and computational lab: 1C

Name: Estella Chin Ning

CID: 00697238

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Background

The dimerisation of cyclopentadiene involves a [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition pericyclic reaction (Scheme 1) and produces specifically the endo dimer 2 rather than the exo dimer 1.

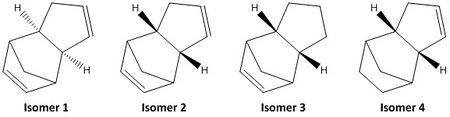

The hydrogenation of dimer 2 initially produces only one of the two dihydro derivatives 3 or 4, only after prolonged hydrogenation does the tetrahydro derivative form (Scheme 2).

For both reactions, the stereoselectivity (dimerisation reaction) and regioselectivity (hydrogenation reaction) is governed by both kinetic or thermodynamic factors; the preference for one isomer over the other indicates whether the kinetic or thermodynamic driving force is higher. The kinetic product is formed via the lowest energy transition state, while the thermodynamic product formed has the lowest energy compared to other competing products.

Results

Calculations of the optimised geometries and energies of the 4 species in Figure 1 were computed using the Avogadro software (MMFF94s force field) and the results were tabulated as shown in Table 1.

| Energy (Kcal/mol) | Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular model (Jmol file) | Isomer 1 | Isomer 2 | Isomer 3 | Isomer 4 |

| Bond Stretching | 3.54309 | 3.46789 | 3.31144 | 2.82310 |

| Angle Bending | 30.77278 | 33.18944 | 31.93278 | 24.68539 |

| Stretch Bending | -2.04142 | -2.08219 | -2.10207 | -1.65719 |

| Torsional | -2.73093 | -2.94947 | -1.46838 | -0.37835 |

| Out-of-plane Bending | 0.01477 | 0.02183 | 0.01308 | 0.00028 |

| Van der Waals' | 12.80146 | 12.35868 | 13.63937 | 10.63723 |

| Angle Bending Energy | 13.01367 | 14.18449 | 5.11949 | 5.14702 |

| Total | 55.37342 | 58.19067 | 50.44570 | 41.25749 |

Analysis & Discussion

Cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene

Cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene produces the endo dimer 2 instead of the exo dimer 1, thus this reaction is kinetically controlled, since isomer 2 is thermodynamically less stable than isomer 1 but is still formed in preference to isomer 1.

The reason behind the kinetically-controlled Diels-Alder reaction has been explained by several theories, which are detailed below:

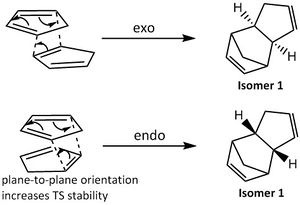

1. It was suggested by Alder [1] that there was "maximum accumulation of double bonds" during endo cycloaddition when the two ring planes are stacked parallel to each other. This plane-to-plane orientation increases the stability of the transition state molecular complex, lowering the activation barrier and hence favouring the formation of the kinetic (endo) product. (Figure 2)

2. According to Woodward and Hoffmann [2], the endo transition state conformation is favoured over the exo conformation due to a higher orbital symmetry present. This allows a larger HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbitals)-LUMO (Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbitals) frontier orbital overlap, due to additional secondary orbital interactions (correct phase p-orbital overlap as depicted by the red dotted lines), increasing its stability and hence decreasing the energy of the transition state. (Figure 3)

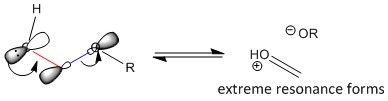

3. In addition, studies carried out on the Diels-Alder transition state [3] suggests an asynchronous cycloaddition mechanism that consists of several resonance structures, one of which is a zwitterion. The zwitterion resonance structure is better stabilised in the endo transition state due to the closer proximity of the two opposite charges, hence this kinetically favours the formation of the endo product. (Figure 4)

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene dimer

If hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer is thermodynamically controlled, Isomer 4 will be formed in preference to Isomer 3. This is because Isomer 4 is energetically more stable (lower total energy) than Isomer 3, as can be seen from Table 1.

The two main contributions to the calculated energy difference between Isomers 3 and 4 are the angle bending energy and the Van de Waals' (VDW) energy, of which the energy difference between the two isomers are 7.25 kcal/mol and 3.00 kcal/mol respectively.

The energy due to bond angle bending arises when angles are bent from their norm; the larger the extent of distortion of geometries away from the preferred one, the larger the angle bending energy contribution. In Isomer 3, the double bond that has been hydrogenated is part of a 5-membered ring, whereas in Isomer 4, the double bond that has been hydrogenated is part of both a 5-membered ring and a 6-membered ring present in a boat conformation. The distortion of geometries and bond angles due to the presence of the double bond is more severe in the latter than in the former, as 2 fused ring structures increases the conformational rigidity of the bonds. This means that there is a greater ring strain contributed by the double bond in the 2 fused ring structures as compared to the double bond present only in the 5-membered ring. Hence, the hydrogenation of that double bond relieves ring strain to a greater extent, allowing the restoration of the preferred bond angles in the two rings and hence decreasing the angle bending energy of Isomer 4 to a larger extent as compared to that of Isomer 3.

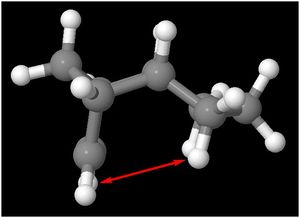

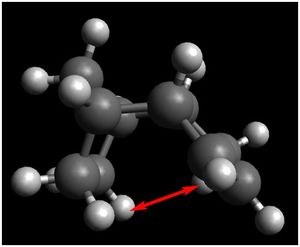

The VDW contribution to the total energy is determined by the distance between two non-bonded atoms present in the same molecule. As the atoms are brought closer together, the VDW attraction between the two atoms increase, corresponding to a decrease in energy. At the VDW radius, the VDW attraction is at a maximum, corresponding to a minimum energy point. As the atoms are brought even closer together beyond the VDW radius, the energy increases due to repulsive forces present. In this case, the H atoms in isomer 3 are 2.752 Å apart while the H atoms in isomer 4 are 2.211 Å apart. Since the VDW radius of a H atom is 1.10 Å (Rowland, 1996)[4] , the optimum distance between 2 H atoms for maximal attractive stabilising forces present is 2.20 Å. Since the distance between the 2 H atoms in Isomer 4 are closer to the VDW radius than that of Isomer 3, this attributes to the lower VDW energy contribution to the total energy.

Distance = 2.752 Å

Distance = 2.211 Å

Background

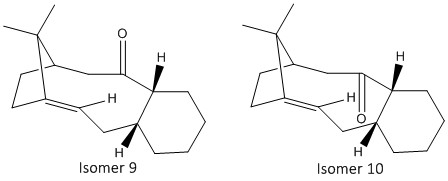

A key intermediate in the total synthesis of Taxol is initially synthesized with the carbonyl group pointing either up (isomer 9) or down (isomer 10) (Figure 7). [5] On standing, the compound isomerises to the alternative carbonyl isomer, this is known as atropisomerism. The stereochemistry of carbonyl addition depends on which isomer is more stable, hence calculations were carried out using the Avogadro software to explore which of the two atropisomers is the more stable.

Results

The geometries were first optimised using the MMFF94s force-field and the respective models of isomers 9 and 10 can be viewed by clicking here (Isomer 9) and here (Isomer 10) respectively. The most stable structures of the isomers consist of the six-membered ring being in a chair conformation, where all its substituents are arranged in a staggered position relative to each other. The results derived from the calculations are tabulated in Table 2.

| Energy (Kcal/mol) | Isomer 9 | Isomer 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | 7.6149 | 7.60232 |

| Angle Bending | 28.30971 | 18.95064 |

| Stretch Bending | -0.07191 | -0.13414 |

| Torsional | 0.42535 | 0.29299 |

| Out-of-plane bending | 0.96182 | 0.85057 |

| Van der Waals' | 33.03740 | 33.08211 |

| Electrostatic | 0.31238 | -0.04490 |

| Total | 70.58893 | 60.59959 |

Analysis and Discussion

The results clearly show that Isomer 10 is the thermodynamically more stable (lower free energy) isomer among the two atropisomers.

In addition, the bridgehead alkene present in both isomers has low reactivity. This observation is unexpected, since according to Bredt's rule [6], double bonds present at bridgehead positions are inherently unstable, especially in strained smaller cyclic systems. However, this ring strain is relieved as ring size increases; in infinitely large ring structures, the olefin present can be as stable as its acyclic analogue. In fact, in some cases, these bridgehead double bonds become extremely stable, even more stable than normal acyclic double bonds. Termed as "hyperstable olefins" by Maier and Schleyer [7], these double bonds contain less strain than their corresponding parent hydrocarbons and have negative olefin strain values. They are hence extremely unreactive. This unreactivity has been attributed to the special stability present due to the cage structure of the olefin (which must be within a certain size range) and to the greater strain present in the parent polycycloalkane, and not due to common factors such as steric hindrance or increased π-bond strength [8].

As such, the observed unreactivity of the olefins in isomers 9 and 10 can be attributed to their hyperstability, as mentioned above. The reason for their apparent hyperstability can be explored by comparing the individual energy contributions of the isomers and their related parent polycycloalakanes. Thus, the parent structures of the isomers were optimised using the same procedure as before, and the energy calculation was carried out. The results are detailed in Table 3.

| Energy (Kcal/mol) | Isomer 9 | Parent Polycycloalkane of Isomer 9 | Isomer 10 | Parent Polycycloalkane of Isomer 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Model (Jmol file) | Isomer 9 | Parent Polycycloalkane of Isomer 9 | Isomer 10 | Parent Polycycloalkane of Isomer 10 |

| Bond Stretching | 7.6149 | 6.94386 | 7.60232 | 6.65014 |

| Angle Bending | 28.30971 | 32.21756 | 18.95064 | 24.76153 |

| Stretch Bending | -0.07191 | 0.32363 | -0.13414 | 0.43606 |

| Torsional | 0.42535 | 9.44036 | 0.29299 | 8.20152 |

| Out-of-plane bending | 0.96182 | 0.23267 | 0.85057 | 0.08059 |

| Van der Waals' | 33.03740 | 32.66820 | 33.08211 | 31.36743 |

| Electrostatic | 0.31238 | 0.00000 | -0.04490 | 0.00000 |

| Total | 70.58893 | 81.82628 | 60.59959 | 71.49727 |

As can be seen from Table 3, the parent polycycloalkanes of both isomers have a higher total calculated energy, and hence are more strained, less stable and more reactive than their olefin analogues. The major contributions to this energy increase are the angle bending and torsional energy components, as highlighted in blue, which depicts the source of hyperstability present. The major reason for this relief of energy from the parent polycycloalkane to the bridgehead olefin is the hybridisation change and associated flattening of the bridgehead position, which results in major geometry and energy alterations [9]. The relief of the large angle strain present in the parent polycycloalkane fused-ring structure can be relieved by the introduction of a double bond, thus reducing the angle bending energy of isomer 9 and 10 relative to their parent polycycloalkane. In addition, when the bridgehead position is sp3 hybridised in the parent structures, an eclipsed conformation will be inevitably formed to accomodate the 2 fused ring structures. This results in a high torsional energy due to the unfavourable interactions between the eclipsed substituents, which can be relieved by the introduction of the bridgehead olefin. The elimination of 2 hydrogen atoms removes their associated torsional energy when they are eclipsed. The sp2 hybridisation of the bridgehead position also tilts the other substituents slightly such that they are no longer totally eclipsed with respect to each other. Therefore, this reduction in torsional strain when the bridgehead olefin is present can be said to be a major contributor to the hyperstability observed in isomers 9 and 10.

Background

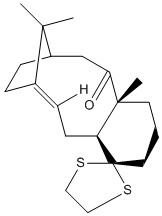

Molecule 18 is a derivative of isomer 10, for which spectroscopic information has been reported [10]. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of molecule 18 was thus calculated and compared with the literature values to see if the latter has been correctly interpreted and assigned.

Method

This was done by first using the MMFF94s mechanics force field in Avogadro to optimise the geometry of the molecule, and then calculating the geometry at the density functional level (DFT) and the predicted NMR spectra on HPC by setting the following parameters:

Calculation: Geometry optimisation

Theory: B3LYP

Basis: 6-31G (d,p)

Keywords used: SCRF=(CPCM,Solvent=benzene) Freq NMR EmpiricalDispersion=GD3

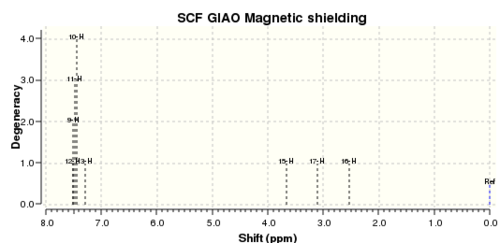

Results and Discussion

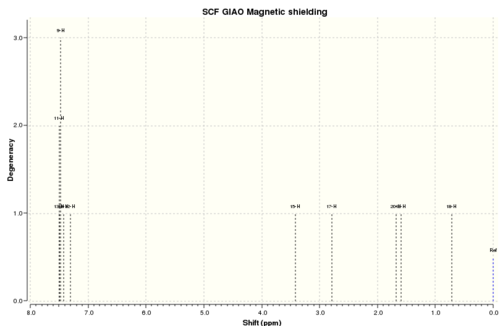

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Benzene

Degenerate peaks are condensed together (Degeneracy Tolerance 0.05)

DOI:10042/27575

1H NMR

Reference shielding: 31.7499 ppm

| No. | Calculated 1H NMR shift (Hydrogen atom assignment) (ppm) | Average Calculated 1H NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 1H NMR shift (300 MHz, C6D6) in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

1H NMR shift (ppm) |

Proton Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 5.97 | - | 5.21 (m, 1H) | -0.76 | 21 |

| 2. | 3.12 (53, 50)

, 2.95 (52, 19), 2.89 (51), 2.80 (18) |

- | 3.00-2.70 (m, 6H) | - | 18,19,50,51,52,53 |

| 3. | 2.80 (40)

, 2.67 (25), 2.54 (28), 2.43 (8) |

- | 2.70-2.35 (m, 4H) | - | 8,25,28,40 |

| 4. | 2.31 (11)

, 1.98 (24), 1.98 (39), 1.83 (10, 27), 1.53 (41) |

- | 2.20-1.70 (m, 6H) | - | 10,11,24,27,39,41 |

| 5. | 2.54 | - | 1.58 (t, 1H) | -0.96 | 14 |

| 6. | 1.53 (4)

, 1.34 (7), 1.21 (5) |

- | 1.50-1.20 (m, 3H) | - | 4,5,7 |

| 7. | 2.31 (44), 1.27 (45), 0.60 (43) | 1.40 | 1.10 (s, 3H) | -0.30 | 43,44,45 |

| 8. | 1.64 (31), 1.21 (32), 0.96 (33) | 1.27 | 1.07 (s, 3H) | -0.20 | 31,32,33 |

| 9. | 1.53(35), 0.96 (37), 0.90 (36) | 1.13 | 1.03 (s, 3H) | -0.10 | 35,36,37 |

When 3 hydrogen atoms are attached to a carbon atom that can undergo free bond rotation, they are said to be magnetically and chemically equivalent. Hence, all 3 hydrogen atoms would only give rise to a single chemical shift in the 1H NMR spectrum, which corresponds to the average of all 3 hydrogen atoms. As such, the calculated 1H NMR shifts corresponding to each individual H atom should be summed and averaged before comparison is made to literature values. This was carried out for hydrogen atoms 43,44,45; 31,32,33; and 35,36,37.

It is evident from Table 4 that while most chemical shift assignments were made correctly in the literature, with minor chemical shift differences from that of the calculated values, there is a huge discrepancy between the values for hydrogen atom 21(-0.76ppm) and 14 (-0.96ppm). Furthermore, the chemical shifts highlighted in blue also falls out of the chemical shift ranges as reported in literature. This divergence in values can be ascribed to various factors:

1. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation is not in the conformation corresponding to the global minimum in terms of energy, due to the limitations of the Avogadro optimising software, which was only able to optimise the structure to an energy local minimum point. This may result in deviations between theoretical and experimental NMR values, if the actual sample used was in its lowest energy conformation.

2. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation was in the lowest energy conformation, however, the actual molecule formed was not the thermodynamic product (lowest energy product) but the kinetic product (formed via the lowest energy transition state). Hence, the actual molecule may differ slightly in terms of conformation from the expected thermodynamically most stable product, causing a deviation between theoretical and experimental NMR values.

3. As NMR is an extremely sensitive procedure, the presence of minor impurities in the sample may cause slight chemical shifts, resulting in differences between the actual NMR spectrum attained and the values calculated using computational studies.

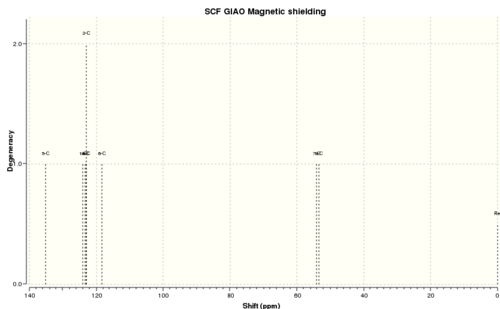

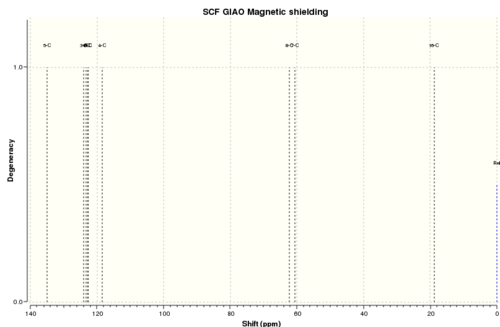

13C NMR

Reference shielding: 192.066 ppm

| No. | Calculated 13C NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 13C NMR shift in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

13C NMR shift (ppm) |

Carbon Atom Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 211.92 | 211.49 | -0.43 | 15 |

| 2. | 147.87 | 148.72 | +0.85 | 20 |

| 3. | 120.12 | 120.90 | +0.78 | 17 |

| 4. | 92.84 | 74.61 | -18.23 | 9 |

| 5. | 65.94 | 60.53 | -5.41 | 12 |

| 6. | 54.93 | 51.30 | -3.63 | 26 |

| 7. | 54.76 | 50.94 | -3.82 | 1 |

| 8. | 49.53 | 45.53 | -4.00 | 29 |

| 9. | 48.03 | 43.28 | -4.75 | 6 |

| 10. | 45.65 | 40.82 | -4.83 | 49 |

| 11. | 44.01 | 38.73 | -5.28 | 48 |

| 12. | 41.47 | 36.78 | -4.61 | 2 |

| 13. | 38.51 | 35.47 | -3.04 | 38 |

| 14. | 33.69 | 30.84 | -2.85 | 42 |

| 15. | 32.47 | 30.00 | -2.47 | 13 |

| 16. | 28.36 | 25.56 | -2.80 | 22 |

| 17. | 26.50 | 25.35 | -1.15 | 34 |

| 18. | 24.44 | 22.21 | -2.23 | 23 |

| 19. | 24.01 | 21.39 | -2.62 | 3 |

| 20. | 22.58 | 19.83 | -2.75 | 30 |

There is good agreement between the experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shift values, with most of the differences present being between an acceptable deviation range of ±5.00 ppm. The 3 carbon atoms that have values deviating more than ±5.00 are carbon atoms 9, 12 and 48, with the most severe deviation belonging to that of carbon 9 with a deviation value of -18.23. This large deviation can be explained by the presence of Spin-orbit coupling errors in carbons attached to "heavy" elements. Carbon 9 is directly attached to 2 sulfur atoms. Thus, its calculated chemical shift requires certain corrections before it can be compared to literature values. The other minor differences can be attributed to the same reasons as detailed above in the 1H NMR section.

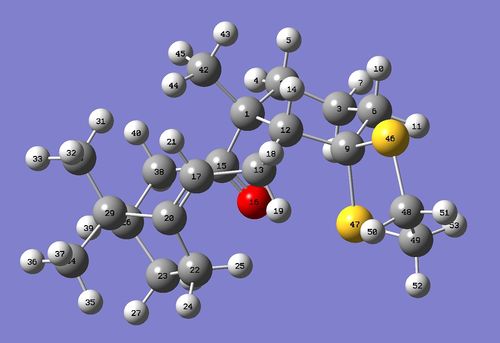

Crystal Structure of 2 Pre-catalysts

Two catalytic systems, namely the Shi asymmetric Fructose catalyst and the Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst, that can be used to epoxide alkenes, will be explored in this section. This will be carried out by searching the Cambridge crystal database (CCDC) using the Conquest program for the pre-catalysts 21 and 23.

The Shi asymmetric Fructose catalyst

Background

Shi et al. [11] devised an original synthetic sequence for the enantioselective epoxidation of trans-alkenes, a portion of which is shown in Scheme 3. Species 21 is the stable precursor to the catalyst, and species 22 is the active catalyst generated from persulfuric acid.

In this section, the extent of the anomeric effect occuring in the pre-catalyst 21 will be analysed by comparing the C-O bond lengths present at the anomeric centres to the C-O bond length found in literature.

The anomeric effect

This is a stabilising interaction that occurs between the lone pair of electrons (n) on the heteroatom and the adjacent C-X σ* sp3 orbital. This n to σ* electron donation is also known as hyperconjugation, and only occurs when the interacting orbitals are aligned parallel to each other. Figure 13 illustrates the process of hyperconjugation, where the structures formed are from complete electron donation and hence represent the extreme resonance structures. In reality, electron donation only occurs partially, these extreme structures do not form and the anomeric effect can only be observed by the lengthening of the blue bond with the removal of electron density, and the shortening of the red bond, due to the increase in electron density from the lone pair donation of electrons. Hence, by analysing the relative C-O bond lengths at anomeric centres, the extent of the occurence of the anomeric effect can be analysed.

Results and Discussion

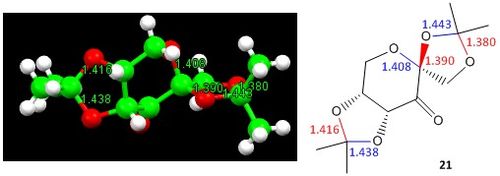

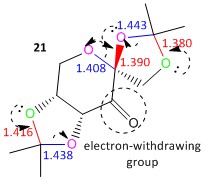

Figure 14 depicts the crystal structure of the pre-catalyst 21 and the annotated C-O bond lengths at the anomeric centres (O-C-O substructures) present. The crystal structure can also be visualised here .

All bond lengths are reported in terms of Å

The typical C-O bond distance is taken to be 1.42 Å [12] and will be used as the basis for comparison in this section.

The difference in the anomeric C-O bond lengths can be explained by the occurence of the anomeric effect in pre-catalyst 21. The direction of the electron movement is shown by the dotted arrows in Figure 15. As the carbonyl group is an electron-withdrawing group, the oxygen atoms that are situated 2 bonds away (β to C=O; coloured in pink) have a relatively lower electron density than the oxygen atoms that are situated 3 bonds away (coloured in green). Hence, the green oxygen atoms have a relatively higher electron density and provides the electron source for hyperconjugation to occur. This results in the relative differences in the bond lengths as depicted; the C-O bonds which experience an increase in electron density become relatively stronger and hence have a shorter bond length than 1.42 Å (1.380 Å and 1.416 Å respectively), while the C-O bonds which experience a decrease in the electron density become relatively weaker and hence have a longer bond length than 1.42 Å (1.443 Å and 1.438 Å respectively). Furthermore, the larger the deviation of the C-O bond lengths from the typical bond length of 1.42 Å, the larger the anomeric effect present. A smaller anomeric effect can be attributed to less effective n and σ* orbital overlap. The 5-membered ring that is fused with the adjacent 6-membered ring is conformationally more rigid and hence the anomeric O-C-O substituent present there would only be able to align the n and σ* orbitals to a lesser extent, causing a smaller anomeric effect. The other 5-membered ring that is part of the spirocyclic compound is conformationally more flexible and thus is able to align the n and σ* orbitals to a larger extent to facilitate the stabilising anomeric effect, causing a larger change in the related bond lengths.

The last anomeric O-C-O substituent, whereby one oxygen atom is part of the 6-membered ring and one oxygen atom is part of the 5-membered ring, consists of C-O bond lengths that are both shorter than the typical C-O bond length of 1.42 Å (1.390 Å and 1.408 Å respectively). This is an unexpected observation that can be explained by the inability of the literature value cited to account for all the C-O bond lengths present, due to possible electron density fluctuations present in a molecule. However, the difference in 2 C-O bond lengths can still be accounted for by the anomeric effect. The oxygen atom that is part of the 5-membered ring has a relatively higher electron density as it acts as the electron sink for the simultaneous adjacent anomeric effect that is occuring. Hence, it now acts as the electron source, causing its adjacent C-O bond to shorten and the other C-O bond to lengthen.

The Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst

Background

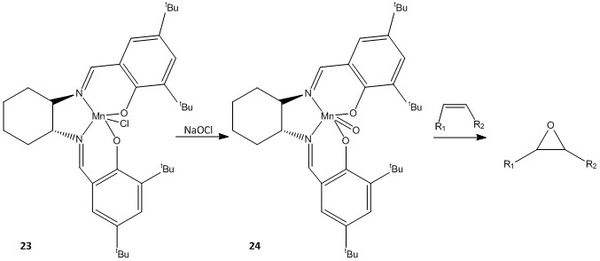

The asymmetric epoxidation of a series of cis-alkenes can be catalysed by the Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst, of which the synthetic sequence has been reported by Jacobsen et. al.[13] [14], and the procedure modified by Hanson [15]. A portion of the synthesis is illustrated in Figure 16.

Species 23 is the stable pre-catalyst and species 24 is the active catalyst generated from NaOCl.

Results and Discussion

The crystal structure of the Jacobsen asymmetric catalyst is shown in Figure 17.

The close approach of the two adjacent tert-butyl groups on the phenyl rings can be quantified by measuring the bond distances present between the hydrogen atoms present on the tert-butyl substituents, the smallest of which is 2.421 Å. This is extremely close to the optimal stabilised distance of 2.20 Å (2 x VDW radius of a H atom [16] ), but not smaller than the VDW distance such that repulsive forces operate. As such, this means that there are strong attractive interactions occurring between the two tert-butyl substituents on the ring, preventing attack of the cis-alkene on that face of the catalyst.

It is also interesting to note that the entire catalyst is largely planar across the whole molecule, with only the chlorine substituent in the pre-catalyst and the oxygen atom in the active catalyst being perpendicular to the plane of the molecule. The molecular model of the pre-catalyst 23 can be viewed here.

This is in accordance to the Jacobsen asymmetric catalysis mechanism, as originally suggested by John Groves to explain porphyrin-catalysed epoxidation reactions [17] Also known as a "side-on perpendicular approach", it was proposed that to facilitate favourable orbital overlap, the substrate (cis-alkene) would approach the metal-oxo bond on the active catalyst in an orientation that is perpendicular to the plane of the catalyst. The substrate approaches the catalyst over the diamine bridge (above the plane of the catalyst), where the steric bulk of the tert-butyl groups and the strong VDW attractive forces present between the two tert-butyl groups (below the plane of the catalyst) prevents the cis-alkene from attacking on that face of the catalyst [18]. The planar conformation of the catalyst also facilitates easy access of the substrate to the perpendicularly-aligned oxygen atom. However, it should be noted that the pathway of the alkene approach to the Jacobsen catalyst is highly debated [19].

Assigning the absolute configuration of two epoxides

NMR Analysis

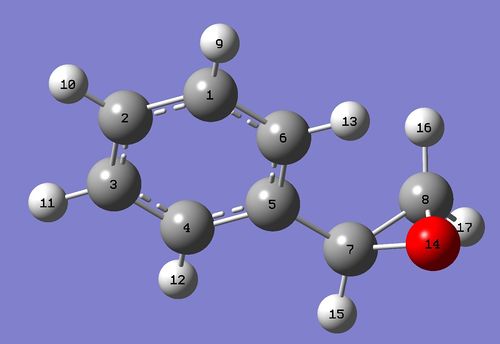

The expected 1H NMR and 13C spectra of styrene oxide (Table 6,7) and β-methyl styrene oxide (Table 8,9) was computed using the same procedure as detailed above, and the chemical shift values obtained were compared to literature values [20] to check the integrity of the compounds reported.

Reference: TMS B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Chloroform

Degenerate peaks are condensed together (Degeneracy Tolerance 0.05)

Styrene Oxide

1H NMR

Reference shielding: 31.7445 ppm

| No. | Calculated 1H NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) shift in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

1H NMR shift (ppm) |

Proton Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 7.49 (9,10,11,12)

, 7.30 (13) |

7.34-7.27 (m, 5H) | - | 9,10,11,12,13 |

| 2. | 3.66 | 3.84 (dd, 1H) | +0.18 | 15 |

| 3. | 3.11 | 3.12 | +0.01 | 17 |

| 4. | 2.54 | 2.81 | +0.27 | 16 |

It is evident from Table 6 that there is good corroboration between literature and calculated chemical shift values. However, it was also observed that the chemical shifts highlighted in blue falls out of the chemical shift ranges as reported in literature. This divergence in values can be ascribed to various factors:

1. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation is not in the conformation corresponding to the global minimum in terms of energy, due to the limitations of the Avogadro optimising software, which was only able to optimise the structure to an energy local minimum point. This may result in deviations between theoretical and experimental NMR values, if the actual sample used was in its lowest energy conformation.

2. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation was in the lowest energy conformation, however, the actual molecule formed was not the thermodynamic product (lowest energy product) but the kinetic product (formed via the lowest energy transition state). Hence, the actual molecule may differ slightly in terms of conformation from the expected thermodynamically most stable product, causing a deviation between theoretical and experimental NMR values.

3. As NMR is an extremely sensitive procedure, the presence of minor impurities in the sample may cause slight chemical shifts, resulting in differences between the actual NMR spectrum attained and the values calculated using computational studies.

13C NMR

Reference shielding: 192.17 ppm

| No. | Calculated 13C NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) shift in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

13C NMR shift (ppm) |

Carbon atom Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 135.1 | 137.6 | +2.5 | 5 |

| 2. | 124.1 (1) 123.4 (3) 123.0 (4,2) 118.3 (6) Average = 122.3 |

128.5 (2 CH) 128.1 (CH) 125.5 (2 CH) Average= 127.2 |

+4.9 | 1,2,3,4,6 |

| 3. | 54.1 | 52.4 | -1.7 | 7 |

| 4. | 53.5 | 51.2 | -2.3 | 8 |

There is good agreement between the experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shift values, with most of the differences present being between an acceptable deviation range of ±5.00 ppm. Thus, it can be inferred that the literature values reported are rather accurate and correctly assigned.

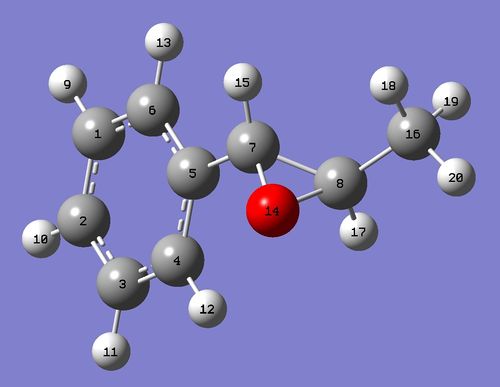

β-methyl Styrene Oxide

1H NMR

Reference shielding: 31.7445 ppm

| No. | Calculated 1H NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) shift in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

1H NMR shift (ppm) |

Proton Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 7.49 (9,11,13) 7.42 (10)

|

7.32 - 7.22 (m, 5H) | - | 9,10,11,12,13 |

| 2. | 3.41 | 3.55 (d, 1H) | +0.14 | 15 |

| 3. | 2.79 | 3.10 (dq, 1H) | +0.31 | 17 |

| 4. | 1.68 (20) 1.59 (19) 0.72 (18) Average: 1.33 |

1.42 (d, 3H) | +0.09 | 18,19,20 |

It is evident from Table 8 that there is good corroboration between literature and calculated chemical shift values. However, it was also observed that the chemical shifts highlighted in blue falls out of the chemical shift ranges as reported in literature. This divergence in values can be ascribed to various factors:

1. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation is not in the conformation corresponding to the global minimum in terms of energy, due to the limitations of the Avogadro optimising software, which was only able to optimise the structure to an energy local minimum point. This may result in deviations between theoretical and experimental NMR values, if the actual sample used was in its lowest energy conformation.

2. The optimised structure used in the NMR calculation was in the lowest energy conformation, however, the actual molecule formed was not the thermodynamic product (lowest energy product) but the kinetic product (formed via the lowest energy transition state). Hence, the actual molecule may differ slightly in terms of conformation from the expected thermodynamically most stable product, causing a deviation between theoretical and experimental NMR values.

3. As NMR is an extremely sensitive procedure, the presence of minor impurities in the sample may cause slight chemical shifts, resulting in differences between the actual NMR spectrum attained and the values calculated using computational studies.

13C NMR

Reference shielding: 192.17 ppm

| No. | Calculated 13C NMR shift (ppm) | Reported 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) shift in literature (ppm) | Difference between cal. and lit.

13C NMR shift (ppm) |

Carbon atom Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 135.0 | 137.9 | +2.9 | 5 |

| 2. | 124.1 (3) 123.3 (1) 122.8 (6) 122.7 (2) 118.5 (4) Average: 122.3 |

128.4 (2 CH) 128.0 (CH) 125.5 (2 CH) Average: 127.2 |

+4.9 | 1,2,3,4,6 |

| 3. | 62.3 | 59.5 | -2.8 | 8 |

| 4. | 60.6 | 59.0 | -1.6 | 7 |

| 5. | 18.8 | 18.0 | -0.8 | 16 |

There is good agreement between the experimental and calculated 13C NMR chemical shift values, with most of the differences present being between an acceptable deviation range of ±5.00 ppm. Thus, it can be inferred that the literature values reported are rather accurate and correctly assigned.

The calculated chiroptical properties

The expected chiroptical properties of the styrene oxide can be calculated and the value attained can be compared against literature values to check if that reported in literature is correct. The calculation of three chiroptical properties would be useful for this experiment:

1. The optical rotation at a specified wavelength of light (the optical rotary power, or ORP)

2. The electronic circular dichroism (ECD)

3. The vibrational circular dichroism (VCD)

However, only the first two would be explored in this project as the appropriate instrument required for the VCD technique is not available in the department.

Optical Rotation

The output of the previous frequency/NMR calculation (i.e. the QM-optimised geometry) was retrieved and an optical rotation (OR) job type was carried out. The results are detailed in Table 10.

| (R)-Styrene Oxide DOI:10042/27578 |

(R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide DOI:10042/27579 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Computed OR value (5890.0 Å) /° |

Literature OR value (5890.0 Å) /° |

Computed OR value (5890.0 Å) /° |

Literature OR value (5890.0 Å) /° |

| +30.32 | +33 [21]; +34.3 [22] | +46.77 | +46 [23]; + 47 [24] |

While there is a good match of the computed OR values to some of the literature OR values found for both epoxides (as cited in Table 10 above), it was also observed that there is a great range (from -24° to 45° for (R)-styrene oxide and from -48° to 131° for (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide) of OR values reported.

In the case of (R)-styrene oxide, this may be due to the presence of the other enantiomer ((S)-styrene oxide) present in the sample used in the experimental optical rotation measurement. The amount of impurity present in the sample will cause a shift in the OR value. If the value reported is a negative value, it can be inferred that there is an excess of the S enantiomer over the R enantiomer. This is because enantiomers rotate plane-polarised light by the same extent but in opposite directions, hence if the computed OR value for the R enantiomer has a positive value, the S enantiomer would be expected to have a negative value of equal magnitude.

In the case of (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide, the range of OR values reported is larger. This is probably due to the possibility of (R,S)- and (S,R)-diastereoismers, in addition to the presence of the (S,S)-enantiomer, present as impurities in the sample. The OR values of diastereoisomers, unlike enantiomers, do not have the same magnitude, and hence this will result in a larger deviation from the OR value of the pure (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide.

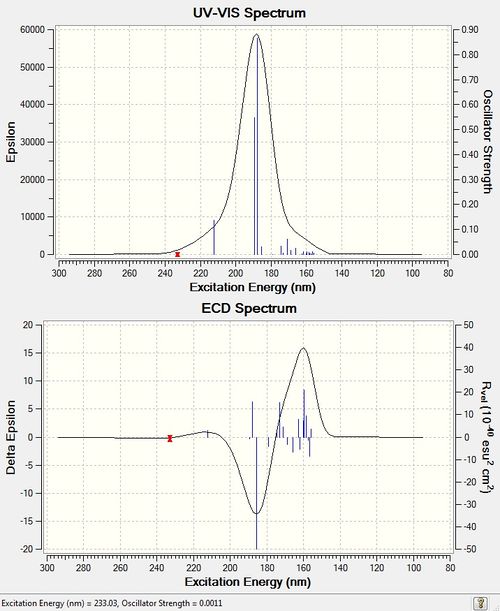

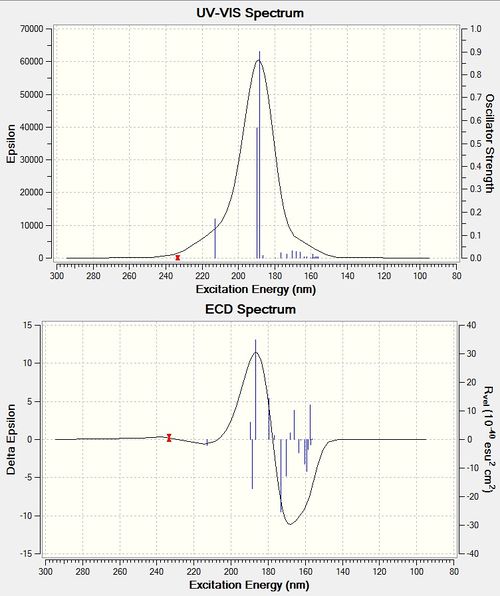

Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD)

The output of the previous frequency/NMR calculation (i.e. the QM-optimised geometry) was retrieved and an Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) job type was carried out. The computed UV and ECD spectra for both epoxides can be visualised in the figures below, although no literature comparison can be made due to the lack of the appropriate chromophore present.

ECD computation of styrene oxide:DOI:10042/27580

ECD computation of β-methyl Styrene Oxide: DOI:10042/27581

ECD is an absorption spectroscopy method based on the differential absorption of left and right circularly polarized light. Optically active chiral molecules will preferentially absorb one direction of the circularly polarized light. The difference in absorption of the left and right circularly polarized light (ΔA) can be measured and quantified by inspecting the ECD spectra. A larger ΔA value depicts a larger difference in absorption between the left and right circularly polarized light, and hence suggests greater chirality of the chromophores present in the molecule. The total ΔA value can be derived from the ECD spectra by adding the difference in the negative and positive amplitudes at their peaks. The ΔA values for styrene oxide and (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide are approximately 30 and 22 respectively. It is unexpected that styrene oxide has a larger ΔA value since it only has 1 chiral centre as compared to 2 chiral centres in (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide. However, since ECD is also affected by the conformation adopted by the molecules, this lower ΔA value may be attributed to the (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide adopting a stabilising conformation that maximises its molecular symmetry, hence reducing its chirality. In other words, the conformation adopted by (R,R)-β-methyl Styrene Oxide was such that partial cancelling of the chiral centres occurred. This is not possible in the case of styrene oxide since the molecule consists of an achiral CH2 group, and hence any conformation reorganizations would not increase molecular symmetry and decrease chirality.

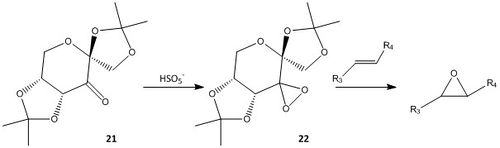

Using the (calculated) properties of transition state for the reaction

For the epoxidation reaction of styrene and trans β-methyl styrene, the computed free energies (G) of the transition states corresponding to the formation of the R,R and S,S enantiomers were individually retrieved by identifying the lowest energy conformer, and the free energy difference (ΔG) between the two diastereomeric transition states were calculated. This value can then be converted to the ratio of concentrations of the two species (K) using the equation K = exp (-ΔG/RT), where T is assumed to be 298.15 K. The value of K can then be used to work out the predicted the enantiomeric excess (ee) of one epoxide over the other, where ee=(K-1)/(K+1). This procedure was carried out for the epoxidation reactions using both the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts. The results are detailed in Tables 11 (Styrene) and 12 (trans β-methyl styrene) below.

| Shi Catalyst Epoxidation | Jacobsen Catalyst Epoxidation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enantiomer | R | S | R | S |

| G (hartree/particle) | -1303.738044 [25] | -1303.738503 [26] | -3343.962162 [27] | -3343.969197 [28] |

| ΔG (hartree/particle) | -0.000459 (GS-GR) |

-0.007035 (GS-GR) | ||

| ΔG (J/mol) | -1205.104592 | -18470.39391 | ||

| K | 1.62606139 | 1722.078989 | ||

| Enantiomeric Excess (%) | 23.84 (S in excess) |

99.88 (S in excess) | ||

| Enantiomeric Excess (lit. value) (%) | 24.3 [29] (R in excess) |

57 [30] (R in excess) | ||

It is evident from Table 11 that while there is a good agreement between the calculated (23.84 %) and literature (24.3 %) enantiomeric excess values for the epoxidation of styrene using the Shi catalyst, the computational studies predicted the S enantiomer to be made in excess over the R enantiomer, which was opposite from the literature result of the R enantiomer being in excess over the S enantiomer. This inaccurate prediction was observed for both the cases of the Shi and Jacobsen catalysts. This highlights the limitations of using computational studies to predict the enantiopurity of the synthesized products using the different catalytic systems.

| Shi Catalyst Epoxidation | Jacobsen Catalyst Epoxidation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enantiomer | R,R | S,S | R,R | S,S |

| G (hartree/particle) | -1343.032443 [31] | -1343.024742 [32] | -3383.254344 [33] | -3383.262481 [34] |

| ΔG (hartree/particle) | -0.007701 (GRR-GSS) |

-0.008137 (GSS-GRR) | ||

| ΔG (J/mol) | -20218.97704 | -21363.69513 | ||

| K | 3486.652172 | 5533.064288 | ||

| Enantiomeric Excess (%) | 99.94 (R,R in excess) |

99.96 (S,S in excess) | ||

| Enantiomeric Excess (lit. value) (%) | 95.7 [35] (R,R in excess) |

20 [36] (S,S in excess) | ||

As can be seen from Table 12, there is a good agreement between the calculated (99.94 %) and literature (95.7 %) enantiomeric excess values for the epoxidation of trans β-methyl styrene using the Shi catalyst. In addition, both the calculation and literature values arrived at the same result that the R,R enantiomer would be made in excess over the S,S enantiomer. The high enantiomeric excess values fits the theory, since the Shi catalyst is known to be an effective catalyst for highly enantioselective epoxidation reactions carried out on trans-alkenes [37] . Thus, as trans β-methyl styrene is a trans-alkene, the high enantioselectivity is expected. This shows that the computed enantiomeric excess value can be used to accurately predict the enantiomeric purity of epoxide products synthesized from trans substrates, using the Shi catalyst.

However, despite both the calculation and literature values arriving at the same result that the S,S enantiomer would be made in excess over the R,R enantiomer, it was also observed that the computed value (99.96 %) for the epoxidation of trans β-methyl styrene using the Jacobsen catalyst deviated significantly from the literature value (20 %). The literature value can be explained theoretically since the Jacobsen catalyst is only effective for the synthesis of enantiopure epoxides from cis-alkenes [38]. Since trans β-methyl styrene is a trans-alkene, it is hardly surprising that the enantiomeric excess value experimentally obtained is on the low side. This also shows that computational studies may be inaccurate in predicting the enantiomeric purity of epoxide products synthesized from trans substrates, using the Jacobsen catalyst.

Investigating the non-covalent interactions (NCI) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

The term non-covalent interactions (NCI) is an umbrella term encompassing hydrogen bonds, electrostatic attractions and dispersion forces between two atoms. These NCI interactions can be defined by the properties of the associated electron density and its curvatures [39]. A NCI analysis diagram is helpful in identifying the interacting regions between the reacting substrate and the catalyst, and thus, explain the origins of stereoselectivity of catalytic reactions.

The NCI present in the transition state for the Shi epoxidation process of trans-β-methyl styrene (R,R series) was investigated in this exercise. This was carried out by computing the electron density for the system [40] and subjecting it to a NCI analysis via the diagram as shown below. In the diagram below, the different colours indicate whether the interaction is attractive or repulsive (blue: very attractive, green: mildly attractive, yellow: mildly repulsive, red: strongly repulsive)

Orbital |

The bond forming in a transition state (visualised as the multi-coloured ring structure above) is considered as half-covalent, and thus this type of NCI interaction is normally ignored in the NCI analysis.

The real NCI interaction can be visualised by the green surfaces present between the catalyst and substrate molecules. The fact that these surfaces are mostly green with slight blue tinges suggests the presence of mildly to strong attractive non-covalent interactions between the catalyst and the substrate molecules. These attractive forces are largely situated in three areas:

1. Between the spirocyclic 5-membered ring of the catalyst and the hydrogen atoms on the methyl substituent of the alkene

2. Between the hydrogen atoms on the methyl substituent of the spirocyclic 5-membered ring of the catalyst and the terminal hydrogen atom of the alkene substrate

3. Between the hydrogen atom present on the 6-membered ring of the catalyst and the phenyl ring of the styrene molecule.

Since these interactions are between non-polar groups, they consist largely of dispersion forces.

The positions of these non-covalent attractive interactions explain why the Shi catalyst has a high preference for the trans-alkene over the cis-alkene. As can be visualised from the molecular model above, the relevant interacting non-polar groups on the catalyst are situated in opposite directions (trans) to each other, and hence can only form sufficient dispersion forces with the trans-alkene, and not the cis-alkene. These attractive forces serve to hold the alkene in the correct orientation with respect to the catalyst for a sufficient period of time, allowing the catalytic activity to occur. This also explains the high enantioselectivity attained for the product of the epoxidation reaction of trans-alkenes using the Shi catalyst, as seen in the computational calculations carried out, and literature values cited in the previous section. Since the trans-alkene is held firmly in a specific orientation with respect to the catalyst (analogous to the active site having a specific 3D conformation and shape), the catalytic activity can only occur through one pathway, which thus forms a single enantiomer. Conversely, the low enantioselectivity attained experimentally for the product of the epoxidation reaction of cis-alkenes using the Shi catalyst can be explained using the same theory. Since there are fewer attractive interactions between the cis-alkene and the catalyst, the cis-alkene can only be held transiently in one orientation to the catalyst, and may possess enough energy to break the weak dispersion forces present. Hence, the cis-alkene may be held in different orientations to the catalyst in one sample. Consequently, 2 different enantiomers may be formed from the epoxidation reaction of the cis-alkene in roughly equal probabilities, leading to the low enantiomeric excess value obtained in literature.

Investigating the Electronic topology (QTAIM) in the active-site of the reaction transition state

The Electronic topology (QTAIM) analysis is complementary to the NCI (non-covalent) analysis, since it includes the electron density in the covalent regions of the molecule as well as the non-covalent interactions present (that can also be identified by the NCI analysis as shown previously). There are 4 different topological critical points, known as a bond critical point (BCP), as well as those associated with nuclei (na), those associated with rings (rcp) and those associated with cages (ccl). Only the BCP would be used in the analysis of the type of interactions present in the transition state for the Shi epoxidation process of trans-β-methyl styrene (R,R series) [41].

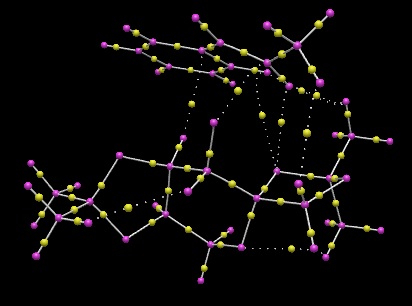

As can be seen from the yellow points (BCP) connected by dotted lines in Figure 26, there are multiple non-covalent interactions present between the catalyst and the alkene. The positions of these interactions correspond to the NCI analysis made above which showed the presence of dispersion forces. Hence, while it is unable to tell from the QTAIM analysis whether the interactions present are attractive or repulsive, the NCI analysis acts as a complementary method to the QTAIM method, providing extra information that the interactions present are attractive (green in the NCI diagram). It is also interesting to note that the position of all the BCPs between the catalyst and the substrate are situated in the middle of the two interacting atoms, emphasizing the equal contribution of the atoms to the non-polar interaction present. This also hints of the non-directionality of dispersion forces, which are formed transiently from fluctuating dipoles, and hence the average non-covalent bond would be formed from roughly equal electronic contributions of the two atoms. The fact that only non-covalent interactions are observed in the active-site of the reaction transition state is expected since these weak interactions only serve to hold the catalyst and substrate in correct positions relative to each other transiently for the catalytic activity to take place. If strong covalent bonds are present between the catalyst and the substrate, it would be difficult to break these bonds after the catalytic activity has occurred, which would be highly undesirable since the catalyst cannot be regenerated, and the product cannot be isolated from the catalyst. In addition, the position of the BCPs present in the covalent interactions present within the substrate molecule and the catalyst molecule tells us the extent of electronic contribution that each interacting atom provides to the bond. It was observed that the BCPs present between C-H bonds are located closer to the H atom. This corresponds to valence bond theory whereby the carbon hybridised orbital is larger than the hydrogen atomic orbital, and hence has a higher chance of electrons residing in the C orbitals. As such, the electronic density is larger around the C atom, causing the BCP to be situated further from C and nearer to the H atom.

Suggesting new candidates for investigations

Similar epoxides can be analysed in the same way as that in this project. A possible epoxide that can be treated similarly is Speciosin B (M/W = 192.171) (Figure 27).

The literature optical rotation reported for this molecule is [α]26 D = +346.3 [42] at 0.4 g/100 mL in chloroform at a wavelength of 589 nm and a temperature of 26 °C.

References

- ↑ K. Alder, G. Stein , Angew. Chem. , 1937 , 50 , 510 DOI:10.1002/ange.19370502804

- ↑ The conservation of orbital symmetry. R. Hoffmann, R. B. Woodward Acc. Chem. Res. , 1968 , 1 , 17 - 22 DOI:10.1021/ar50001a003

- ↑ Mechanistic aspect of Diels-Alder reactions : A Critical Survey. J. Sauer, R. Sustmann Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. , 1980 , 19 , 779 - 807 DOI:10.1002/anie.198007791

- ↑ Batsanov, Inorganic Materials. 2001, 37, 871–885 DOI:10.1023/A:1011625728803

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Bredt, J.; Thouet, H.; Schnitz, J. Liebigs. Ann. Chem. 1924, 437, 1. DOI:10.1002/jlac.19244370102

- ↑ Maier, W. F.; Schleyer, P. V. R, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981, 103. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ W. F. Maier, P. Von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103.DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ Kim, J, Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 1997, 18 (5), 488-495

- ↑ Spectroscopic data: L. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard, R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,, 1990, 112, 277-283. DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ O. A. Wong , B. Wang , M-X Zhao and Y. Shi, J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 335–6338 DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ Glockler, G. Carbon–Oxygen Bond Energies and Bond Distances. J. Phys. Chem. 1958, 62, 1049–1054 DOI:10.1021/j150567a006 .

- ↑ E. N. Jacobsen , W. Zhang , A. R. Muci ,J. R. Ecker , L. Deng J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113, 7063–7064; DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ M. Palucki , N. S. Finney , P. J. Pospisil , M. L. Güler , T. Ishida , and E. N. Jacobsen, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1998, 120, 948–954;DOI:10.1021/ja973468j

- ↑ J. Hanson,J. Chem. Educ., 2001, 78, 1266 DOI:10.1021/ed078p1266

- ↑ Batsanov, Inorganic Materials. 2001, 37, 871–885 DOI:10.1023/A:1011625728803

- ↑ Groves, JT; Nemo, TE, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1983, 105 (18): 5786–5791 DOI:10.1021/ja00356a015

- ↑ Jacobsen, Eric N.; Zhang, Wei; Muci, Alexander R.; Ecker, James R.; Deng, Li , J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1991, 113 (18): 7063. DOI:10.1021/ja00018a068

- ↑ McGarrigle, EM; Gilheany, DG, Chem. Rev., 2005, 105 (5): 1563–1602.DOI:0.1021/cr0306945

- ↑ Chen, Xin-Zhi; Ji, Li; Qian, Chao; Wang, Ya-Na; Qian, Chao Synthetic Communications, 2013 , 43 (16), 2256 - 2264 DOI:10.1080/00397911.2012.699578

- ↑ Farmer, Peter B.; Matthews, Lee; Ellis, Martin K.; Cullis, Paul N. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals, 1997, 39 (6), 479 - 486

- ↑ McKinstry, Lydia; Myers, Andrew G. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1996 ,61 (7), 2428 - 2440 DOI:10.1021/jo952032o

- ↑ Besse; Renard; Veschambre Tetrahedron Asymmetry, 1994 ,5(7), 1249 - 1268 DOI:10.1016/0957-4166(94)80167-3

- ↑ Fronza; Fuganti; Grasselli; Mele Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1991 , 56 (21), 6019 - 6023 DOI:10.1021/jo00021a011 10.1021/jo00021a011

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C20H26O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.822137

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C20H26O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.826003

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C36H44ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.860449

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C36H44ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.860441

- ↑ Wang, Z.; Tu, Y.; Frohn, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11224–11235. DOI:10.1021/ja972272g 10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ Zhang, W.; Loebach, J. L.; Wilson, S. R.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2801–2803 DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.739117

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.856651

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C37H46ClMnN2O3. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10042/25945

- ↑ Wang, Z.; Tu, Y.; Frohn, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11224–11235.DOI:10.1021/ja972272g 10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ Zhang, W.; Loebach, J. L.; Wilson, S. R.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2801–2803 DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052

- ↑ Wang, Z.; Tu, Y.; Frohn, M.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 11224–11235. DOI:10.1021/ja972272g 10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ Zhang, W.; Loebach, J. L.; Wilson, S. R.; Jacobsen, E. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 2801–2803.DOI:10.1021/ja00163a052

- ↑ J. L. Arbour, H. S. Rzepa, J. Contreras-García, L. A. Adrio, E. M. Barreiro, K. K. Hii, Chem.Euro. J., 2012, 18, 11317–11324 DOI:10.1002/chem.201200547

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Rzepa, Henry S. (2013): Gaussian Job Archive for C21H28O7. figshare. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.738037

- ↑ Dong, Ze-Jun; Jiang, Meng-Yuan; Liu, Ji-Kai; Liu, Rong; Zhang, Ling; Jiang, Meng-Yuan; Liu, Rong; Zhang, Ling Journal of Natural Products, 2009 ,72 (8), 1405 - 1409 DOI:10.1021/np900182m