Rep:Mod:DOR1124

Abstract

Relevant theory and software background was discussed to provide foundations for the report. An initial calculation was performed to check the computational software. The phonon dispersion was determined for MgO, and the properties of this dispersion were discussed along with an attempt at rationalising the shape. The optimal grid size for determining a Density of States that stands in good agreement with experiment was found to be 24 x 24 x 24. This grid size proved to be an efficient compromise between trueness to experiment and computational expense. Increasing the grid size further led to a dramatic increase in computational time, with negligible improvement on the results obtained with the aforementioned optimal grid size. Furthermore, the optimal grid size for determining the Helmholtz Free Energy was also determined to be 24 x 24 x 24. Similarly, doubling the shrinking factor during these computations was found to increase the computational time with negligible improvement on the measurement. The thermal expansion coefficients were determined under the quasi-harmonic approximation and a molecular dynamics simulation. An attempt was made to try and rationalise the discrepancy in the obtained values.

Introduction

Background

In the last half century, computational methods have opened up an impressive range of information about chemical systems that would be otherwise difficult to obtain. The proliferation of computers over the last 30 years has led to many more widespread investigations being carried out. Much more attention has also been given to atomistic calculations (as opposed to the modelling of electrons and other subatomic particles, which was the main focus prior to important developments in atomistic computing) and these calculations constitute the bulk of this report. Early computational methods, while they may be considered primitive, could still be used to determine, quite accurately, the lattice energy.1 This report begins with a brief introduction to the MgO system that was in question, followed by a short discussion of the methodology and software used. The initial determination of the internal energy of an MgO crystal acts as an introduction to the software. Subsequently, the phonon modes of MgO are investigated, and the density of states is determined for varied sizes of k point grids. The Helmholtz free energy is then determined for a number of grid sizes, and the optimal grid size for convergence to values for an infinite grid are determined. The thermal expansion of MgO is then investigated, followed by a final molecular dynamics treatment of the MgO supercell.

The system under study

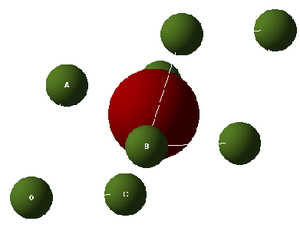

In this experiment, the simple binary oxide, MgO was studied. This oxide is found in nature as its ore, periclase. This ore is the cubic form of magnesium oxide - particularly suitable considering much of this experimentation relies on the highly symmetric cubic conventional cell of MgO. Examine Figure 1, which shows the conventional cell of MgO. The cubic symmetry in this species is easy to see - and the importance of this symmetry will become apparent throughout the report. This particular cell contains 4 formula units of MgO i.e. 4 atoms of magnesium and 4 of oxygen. There are 8 Mg atoms on corners of the cell, and 6 Mg atoms on the faces of the cell. The 8 corner atoms of Mg are shared with 8 other cells, and so correspond to one actual atom. The Mg atoms on the faces are each shared between 2 cells - therefore giving rise to 3 actual atoms. This accounts for the 4 Mg atoms in the conventional cell. There are 12 oxygen atoms on the edges of the unit cell, each shared between 4 cells in total. This, therefore corresponds to 3 actual oxygen atoms. Furthermore, there is one oxygen atom in the very centre of the conventional cell. This represents one oxygen atom, therefore accounting for all 4 oxygen atoms in the conventional cell.

As was mentioned, the conventional cell is important for seeing the inherent symmetry in the MgO crystal. There is, however, an alternative cell representation - the primitive cell which is shown in Figure 2. It is the simplest cell that still stays true to the representation of the periodic MgO lattice. This primitive cell is hexagonal, as opposed to the cubic conventional cell. An important thing to note is that a conventional cubic cell can be reduced to a primitive cell with no loss of generality (the symmetry is easier to visualise when using the conventional cell, but all other important information is retained even when using the primitive cell). The benefit of this change in unit cell will become apparent in the section discussing the software used during these computations. The primitive cell consists of a single MgO formula unit i.e. one atom of Mg and one atom of oxygen. This can be rationalised as follows: 8 Mg atoms appear on the 8 corners of the cell, and therefore these are shared between 8 cells in total. This corresponds to one actual Mg atom in the cell. There is also one oxygen atom in the very centre of the primitive cell - thereby accounting for the single oxygen atom in the primitive cell. Figures 1 and 2 show the conventional and primitive cells, respectively. Note that the atoms in green correspond to Mg, while the larger red atoms represent O.

In order to define the geometry of a unit cell completely, one needs 6 quantities: a, b, c, , , , where a, b, and c are the lattice vectors, each acting in one of the cardinal directions (x, y and z respectively). is the angle between the b and c lattice vectors, is the angle between the a and c lattice vectors and, finally, is the angle between the a and b lattice vectors. Fortunately, both the conventional and primitive cells can be defined using only 1 lattice vector and 1 angle. In both cases, a = b = c therefore the lattice vectors can be completely defined using only a single lattice vector. In the conventional cell, = = = , where the subscript C indicates that the conventional cell is being discussed. Analogously, = = = , where the subscript P indicates that the primitive cell is being discussed. Thus, in both cells, knowing only one length, one can fully define the geometry of the cell. In order to fully define all properties associated with the unit cells, one also needs to know the number of atoms within each cell and also the relative positions of these atoms. Indeed, looking back to Figures 1 and 2, the basis lattice vectors are labelled as A, B, and C. Also, the origin (from which all vectors are measured) is denoted by O.

One more type of cell that should be mentioned is the supercell. These kinds of cells are made up of a large number of unit cells, and they are useful when the system needs to have a higher degree of vibrational freedom i.e. more space for the atoms to move around. In this report, the supercell is discussed when molecular dynamics are used. They are particularly useful for molecular dynamics, seeing as a molecular dynamics simulation of a single cell would be meaningless.

Methodology

Vibrations in a lattice

If one considers a linear chain of atoms, and assumes that the movement of each atom is coupled to its neighbours, then it is possible to visualise a wave propagating through a lattice. This propagating wave will (of course) have an associated wavelength, and therefore an associated frequency. If the chain in question is allowed to become infinite, there will be an infinite number of possible frequencies of these propagating waves. However, this becomes difficult to model and it is more amenable to consider a finite chain of atoms in the lattice. If each atom is then modelled by a quantum oscillator, the number of possible frequencies of vibration becomes finite. Each of these frequencies is associated with a propagating wave. Analogous to the wave particle duality of radiation (i.e. photons), these propagating waves may be modelled as particles, called phonons. The frequency of the atomic vibrations depends on the wave vector, k. This wave vector k is used to define the dispersion relation, from which much information can be gained.

The harmonic and quasi-harmonic approximations

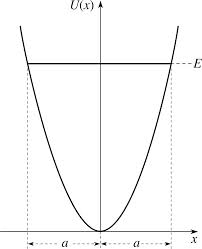

Within the harmonic approximation, the potential has a parabolic functional form. This approximation assumes that the equilibrium bond distance between two atoms does not change with temperature. This is a gross oversimplification, but would be acceptable at very low temperatures - when thermal population of the vibrational modes is minimal, and the equilibrium bond length between two atoms does not change considerably. The main problem with this approximation is that the equilibrium bond distance does change with increasing temperature. As a result, the complexity of the model must be increased.

The quasi-harmonic approximation is still parabolic, but is slightly better than the purely harmonic approximation. This new model allows the equilibrium bond length to change with increasing temperature. Say the system is at 0 K, with a particular equilibrium bond distance, , and under the harmonic potential the parabola will be centred around . As the temperature increases, the atoms will vibrate more rapidly and this leads to the system travelling up one of the parabolic walls. As a result, the equilibrium bond length will increase to . Now, within the quasi-harmonic approximation, a new parabola is considered, centred at . This process is repeated as necessary, to produce a large number of parabolic potentials, each centred at different equilibrium bond lengths. A further caveat of this behaviour is that the quasi-harmonic approximation treats each atom as an independent quantum oscillator, and assumes that all the vibrations are not coupled. This then allows the vibrational energy levels of the system to be determined, and thus necessitates the use of a partition function to describe the Helmholtz Free Energy. This final point is discussed elsewhere in the report. Although the quasi-harmonic approximation allows for an increasing equilibrium bond length at higher temperatures; it still does not model dissociation in the limit of large bond distances. This is where molecular dynamics shines.

The molecular dynamics approach

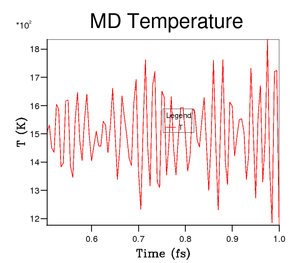

A molecular dynamics approach relies exclusively on Newton's second law of motion i.e. , where is the force on an atom i, is the mass of atom i and is the acceleration of atom i. At each point in time, the forces on every single atom are computed. The time between measurements of force is known as the timestep, and can be set by the experimenter to suit their needs. Once the forces on each atom have been determined, they are accelerated using Newton's second law, and then the atoms are moved accordingly. Once they have been moved for the timestep in question, the new forces are determined, and the subsequent new acceleration is determined. This process is then repeated for a large number of steps, and any thermodynamic properties may be then determined from an average over their values at a large number of timesteps. Take, for example, the plot in Figure 4, which shows the variation in temperature with time during a given molecular dynamics simulation at 1500 K. Clearly, the fluctuations in temperature are visible, but these fluctuations occur around an average value of 1500 K. A similar behaviour will be seen for any other thermodynamic quantities determined using molecular dynamics e.g. volume, Helmholtz/Gibbs free energies. The fluctuations are modeled by a Gaussian distribution, and become less and less important for a large system size. The MgO system under study is quite small, and so the molecular dynamics approach is not perfect, but it still provides an alternative model to the quasi-harmonic approximation. An approach that utilises molecular dynamics means that there is no need to use the harmonic approximation. These two methods are complementary.

The molecular dynamics approach requires significantly more computational time, but is beneficial in that it allows the bonds between adjacent atoms to break by considering the interatomic potential to be a Lennard-Jones potential, shown in Figure 5. This potential shows asymptotic behaviour at large separation, thus allowing the atoms to separate to infinite distance. This is not taken into account when using the quasi-harmonic approximation, and is the major drawback of this model. The benefit of using a quasi-harmonic approximation comes from the fact that the computational expense is significantly reduced.

Software

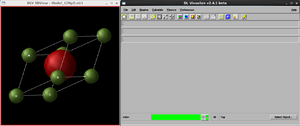

As a platform for visualising the crystals under study, the unix based program DL Visualise was used. This allows manipulation of the crystal cells (scaling, rotation etc.) and will allow labelling of the atoms and lattice parameters. Figure 6 shows the interface of the DLV program, along with the visualisation of a MgO primitive cell.

In terms of calculations of properties of the cell under study, the General Utility Lattice Program (GULP), developed by J. Gale et al2, was used. The basis of the calculations are symmetry adapted algorithms that determine the first and second derivatives of energy for the crystal, and then use these values to determine various thermodynamic parameters of the system. The main paradigm shift that came with the implementation of this program is the use of inherent symmetry to reduce the computational expense.

As with many computational methods, the first step in the GULP algorithms is to determine the internal energy of the system under study. With this first step comes the first approximation - it is assumed that all electrons are held close to the corresponding atoms and that any contribution they have to the internal energy is largely focussed around these atoms. This simplifies the problem greatly. The actual internal energy of a system is dependent on the positions and momenta of all atoms and electrons in the system - so this reduction in complexity is invaluable. A further simplification is possible. The internal energy, U, of a system of N atoms is determined via the expression below:

Where the initial term in the expression is the self energy of each atom, i. The second term is the pairwise interaction between an atom i, and a different atom j. The third term constitutes the three body interaction between atoms i, j and k. The expression will continue, with more terms making up higher order interactions. For many systems, and in particular MgO, the contributions at higher order become less and less significant and therefore may be ignored. Further, as the distance between two atoms increases the interaction between them will become weaker. Thus, introducing cutoff points for any interatomic potential will further simplify the problem.

Next, the nuclear coordinates are treated in order to determine the free energy for the system under study. These nuclear coordinates are varied in order to probe the minimum energy orientation, and the first and second derivatives of this free energy are computed in order to evaluate thermodynamic parameters.

The Coulomb potential is the main contributor to the potential of an ionic material such as MgO. It being a long range potential, the more atoms in a system, then the more complex the terms of the Coulomb potential will become. The interactions will die away slowly, meaning that accurate determination of the Coulombic potential in a periodic, ionic solid is extremely complex. Thus, additional constraints must be placed on the system in order to fully appreciate the Coulomb contribution to the internal energy. The most widely employed solution to this three-dimensional problem is that of the Ewald summation. The details of this method are not suited for this report, but a basic description is as follows. Certain restrictions are imposed on the system to allow convergence of the series in question (something that would not be apparent if one considered a purely Coulombic series). Furthermore, Laplace transforms are performed on any Coulombic terms to yield two different series - one which is rapidly converging in real space and one in reciprocal space (the higher order terms of which can be neglected).

As was mentioned, the Coulombic potential contributes the largest part of the internal energy. The next largest contribution to the internal energy is the energy that arises from interactions between neighbouring dipoles. This is the dispersion interaction. Not much more will be discussed of this potential, but it is good to note that the Ewald summation is used again.

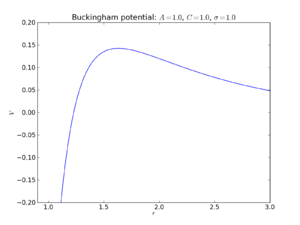

These two previous potentials are long range potentials, and now the discussion must turn to short range potentials. These potentials arise from interactions between ions that are in direct contact with each other. The potential used for MgO within GULP is the Buckingham potential, shown in Figure 7. Note that this is particularly suited to ionic solids, as this potential is used to model atoms or ions that are not directly covalently bonded. If a covalently bonded material was under study, a Morse potential would be much better suited. The expression for the Buckingham potential is given below:

Where A, B and C are constants associated with the potential ( x and for magnesium atoms in this experiment), and r is the interatomic separation. The first term on the right is the attractive term (the force obtained from the first derivative of this term is negative) while the second term on the right is the repulsive term (the force obtained from the first derivative of this term is positive). Note also, the sixth power inverse dependence on interatomic separation. Due to the importance of this repulsive potential only acting over a small range, a cutoff point is imposed during the calculation, which is 12 Angstroms in this case. This fulfils the criterion of a short range potential.

These tools are the very fundamentals of these GULP calculations, but there is a much richer theory that is, unfortunately, not pertinent to the task at hand. As a final note, the discussion should return to the effect of symmetry adaptation. As was mentioned in the previous section, the primitive and conventional cells of MgO are alternative representations of the same system. If the conventional cell is being visualised in DLV, and the experimenter desires to run a particular calculation; GULP will not run the calculation on the conventional cell. In order to reduce the computational cost of any simulations, the conventional cell is reduced to the simpler (but still suitable) primitive cell. Immediately, the benefit of being able to represent MgO as this simple cell becomes apparent. The expression below2 is used within GULP to determine the number of interacting ion pairs that must be considered:

Where denotes the total number of species within the cell. For a primitive cell, the total number of interacting ion pairs is 3, while that for the conventional cell is 36. Clearly, only having to consider 3 ion pairs is much easier than the alternative of 36.

The internal energy of a MgO crystal

In order to facilitate introduction to the computational methods and software in use, the internal energy of a MgO crystal was calculated at 0K. The simplicity of this initial calculation was appropriate for checking whether the computations work, and to familiarise the experimenter with the DLV and GULP interfaces. The internal energy of the crystal was determined to be -41.07532 eV per primitive unit cell. Furthermore, the lattice constant for the conventional MgO cell was found to be 4.21 A, in good agreement with the literature value of 4.21 A.3

The phonon modes of MgO

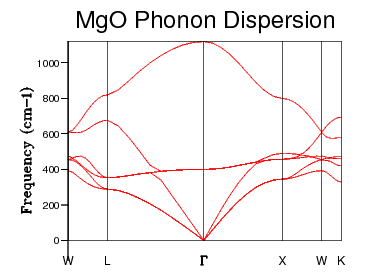

Consider an infinite, one dimensional chain of hydrogen atoms. Each unit, of length in this infinite chain consists of one hydrogen atom. Each hydrogen atom can vibrate in phase or in antiphase. At a wavevector of , all of the hydrogen atoms in the chain will be vibrating in phase. At a wave vector of , all of the hydrogen atoms will be vibrating in antiphase. Between these two extremes, there will be many k values that correspond to a variety of combinations of in phase and antiphase vibrational relationships between adjacent hydrogen atoms. This will give rise to a single branch in the dispersion curve, corresponding to the possible vibrational frequencies of this one dimensional chain of H atoms. Now, instead, consider that each unit cell in this 1D chain contains 2 hydrogen atoms. Clearly, the unit cell length, say is now equal to . Since this unit cell in direct space has doubled in size, the unit cell in reciprocal space must half in size (due to the inverse proportionality between lengths in direct and reciprocal space). As a result, the magnitude of k will only run from zero to and therefore this would lead to some of the information about the frequencies of vibrational modes being lost. This is not acceptable, as any properties gained from a dispersion relation will be intensive i.e. independent on the quantity of material. Thus, doubling the size of the unit cell in direct space; thereby halving the unit cell in reciprocal space, should not have any effect on the available vibrational modes - they exist regardless of the size of the unit cell. To account for this, the region of the branch that occurs in the range is folded back around the "new" edge of the first Brillouin zone, leading to two branches in the dispersion curve. For the hydrogen example, this leads to a pair of degenerate levels at the new boundary at corresponding to the same combination of in phase and antiphase vibrations, but shifted slightly. Some parallels may be drawn with MgO. In the MgO case, the unit cell does indeed contain two species, and therefore the "folding" process will be apparent. The unit cell, however, of MgO contains two different species; whereas the hydrogen chain was homogeneous. This has the effect of breaking the degeneracy at the boundary, leading to an opening of the branch structures. Furthermore, the system under study is three dimensional. Thus, each atom in the unit cell will have 3 degrees of translational freedom, thereby leading to 6 branches in the dispersion curve. These vibrational modes are determined at a number of k points along certain paths in the Brillouin Zone, denoted . These are simply conventions used by crystallographers, and denote interesting symmetry zones within the 1st Brillouin Zone of an fcc lattice. The dispersion curve was determined for 50 k points moving through these symmetry points, and is shown below.

Phonon Dispersion Curve

Figure 8, above, shows the phonon dispersion. The 6 branches are present, as expected from the 3 degrees of freedom associated with each Mg atom and the 3 degrees of freedom associated with each O atom in the unit cell. Examining the boundaries of the Brillouin zone, the experimenter sees that there is indeed an opening of the branches i.e. a breaking of degeneracy. This is as expected for the unit cell of MgO. The branches which go to zero frequency at correspond to a vibrational state in which all atoms are vibrating in phase. These branches then tend to a high frequency at the edge of Brillouin Zone (point ). This corresponds to a vibrational state in which some portion of the atoms are vibrating in antiphase. These modes that tend to zero at small k values (i.e. long wavelengths) are known as acoustic phonons. Note also, that these branches are linear at these long wavelengths. These phonons have the same speed as the speed of sound in MgO (note that the derivative of a branch is the group velocity of the phonons). These acoustic phonons are present in the dispersions of any material, with any kind of unit cell (a material, such as MgO, with two types of atoms in the unit cell have three acoustic modes. The other branches are called optical branches. These are so called because they consist of modes than can be excited by infrared radiation. These occur only in systems with unit cells containing at least two different units. These branches go not go to zero in the centre of the Brillouin Zone. The reason for this is that these modes correspond to vibrations in which all atoms are in antiphase with their nearest neighbours. Positive and negative ions that are adjacent to eachother will vibrate towards eachother, which sets up a dynamic dipole moment, thereby ensuring a non zero frequency at the centre of the Brillouin Zone.

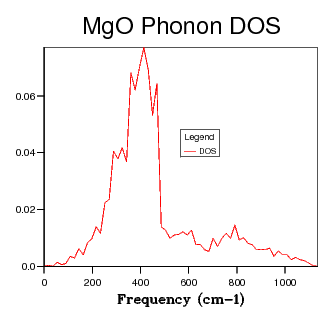

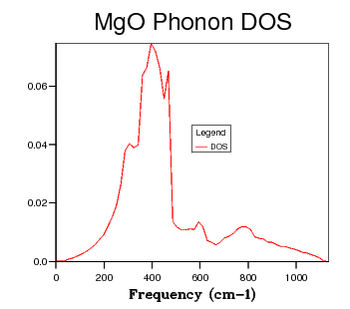

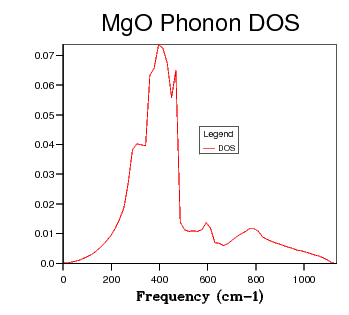

Phonon Density of States

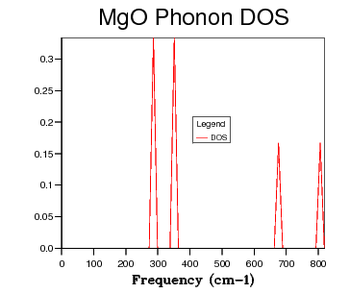

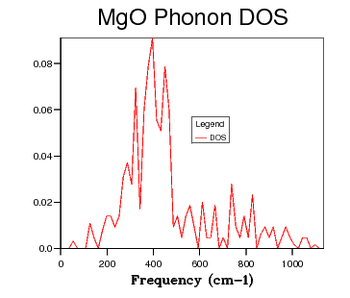

If one was to consider a simple diatomic molecule, it would be easy to predict the different vibrational modes possible. Clearly as the number of atoms in the system increases, so does the number of possible vibrational modes. In a large, periodic system such as MgO, it would be a waste of time to try and predict the manifold vibrational modes and the energy associated with each of them. Thus, the density of states (DOS) is used to represent the number of available vibrational modes at a given energy. It is actually the number of available modes within an infinitesimally small energy range. A common misconception that should be discussed is that the density of states describes the number of vibrational modes at a given energy, but it is completely unrelated to the number of phonons that occupy those modes.

| Grid Size | Phonon Density of States |

|---|---|

| 1 x 1 x 1 |  |

| 6 x 6 x 6 |  |

| 12 x 12 x 12 |  |

| 24 x 24 x 24 |  |

| 48 x 48 x 48 |  |

Table 2 shows a selection of DOS plots for a selection of grid sizes. Consider, first, the DOS obtained from a 1 x 1 x 1 grid of k points (a single k point). This DOS shows 4 discrete peaks, and is not very useful. Since the DOS is obtained as an average over a large number of k points; using a single k point will not provide much information. The k point in question used to obtain this DOS is the L point of the first Brillouin Zone. As the grid size is increased to 6 x 6 x 6, the DOS becomes markedly more continuous. This shows that there are a greater number of available vibrational modes. There are, however, still some points of discontinuity. This is not acceptable, as there is no reason for a given energy interval to have absolutely zero available vibrational modes. A further increase to a 12 x 12 x 12 grid shows yet another increase in continuousness, but it is still not acceptable. The DOS obtained for this grid size is not smooth, implying significant discontinuities in the number of modes available at adjacent energy intervals. While some intervals will be less full than others, the DOS should be considerably smoother. The DOS obtained from the 24 x 24 x 24 grid displays this desired smoothness, and is sufficiently close to DOS plots obtained via neutron scattering experiments of MgO6. Finally, examining the DOS obtained from a 48 x 48 x 48 grid, one sees that there is little improvement when compared to the previous entry. This negligible improvement came with the cost of severely increased computation time. Thus, 24 x 24 x 24 was chosen as the optimal grid size and used for optimisation studies. The Density of States is inherently related to the dispersion relation. The flatter a branch in the dispersion relation, the more energy levels are available in a given energy interval, and therefore the greater intensity of the DOS curve. Examining all of the DOS curves above, they all show the steepest peak to be within the frequency range of 350 - 450 wavenumbers. Looking back to the dispersion relation, a very flat band can be seen to run across the Brillouin zone precisely in this frequency range. This accounts for the high intensity of the DOS at this range. Examining the DOS at 600 wavenumbers, one can see that the intensity is quite low. This suggests that there are very few available vibrational levels within this energy range. Looking, again, at the dispersion relation, one sees a particularly steep branch within the region of the Brillouin Zone, thereby accounting for the low density of states at this energy.

The question now arises as to whether or not this optimal shrinking factor is appropriate for some other systems. If a similar binary oxide is considered, such as CaO, it would be expected that the optimal grid size for MgO should also be suitable. Both of these oxides have the same (fcc) conventional cell. The lattice parameters for these two oxides is very similar, and it follows that the Brillouin Zones for these oxides should be of very similar sizes. Therefore, the optimal shrinking factor for MgO samples a sufficient number of points to provide a good resolution. It follows that the same grid size will provide a good resolution for CaO, and thus this optimal grid size is also suited to simulations of a similar binary oxide. The optimal shrinking factor of 24 is a multiple of 6. This may be related to the inherent 6-fold symmetry of any cubic system, but this is a weak argument with little foundation.

If, now, a zeolite e.g. faujasite is considered, it is unlikely that the same shrinking factor here will be acceptable. The lattice parameter of faujasite is on the order of 24 A. This is much larger than that for MgO. Since the unit cell in direct space is approximately 6 times as large, the unit cell in reciprocal space will be approximately 6 times smaller. In order to keep the same resolution as was achieved with MgO, the sampling must be reduced. Therefore, the optimal grid size for MgO is too large for use in faujasite. Perhaps a shrinking factor of 4 would be suited to modelling a zeolite.

Metals, such as lithium, are very different from binary oxides and zeolites. Metals consist of a regular array of cations in a sea of delocalised electrons. This delocalised nature of the electrons leads to a very wide branch in the dispersion relation for a metal. As such, the shrinking factor of 24 is not suited to metals - they require much larger sampling in order to get an accurate picture. A shrinking factor of 48, or perhaps 96 may be suitable for a small metal such as lithium. There may also be a more fundamental problem when trying to model lithium. Since this compound is a metal, it is unlikely that the repulsive Buckingham potential used for MgO will be suitable. As such, another selection of potentials is likely to be needed for modelling a metal.

The quasi-harmonic approximation and the free energy of MgO

Despite the fact that the discussion thus far has consisted mainly of frequencies, the frequency of a vibration is directly related to the energy by the equation below.

where is the frequency in wavenumbers, is the energy in Joules and h is Planck's constant with units of Joule-Second. This expression assumes that each phonon acts as a quantum oscillator.

In order to compute the free energy of a MgO crystal at a more realistic temperature (300K in this case), the vibrational modes in a crystal are used to determine the energy, and this is averaged over all possible vibrational modes in the crystal. To obtain a perfectly accurate value of the free energy, an infinite crystal (possessing an infinite number of vibrational modes) would be required for the calculation. Since this is computationally impossible, an experimenter must make use of a grid size that can approximate an infinite crystal. The question then arises as to what size of grid is sufficient to allow an accurate value of free energy to be determined.

| Grid Size | Helmholtz Free Energy / eV | Number of k points sampled | Accuracy / eV |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 x 1 x 1 | -40.930301 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 2 x 2 x 2 | -40.926609 | 4 | 0.1 |

| 3 x 3 x 3 | -40.926432 | 18 | 0.001 |

| 4 x 4 x 4 | -40.926450 | 32 | 0.0001 |

| 5 x 5 x 5 | -40.926463 | 75 | 0.0001 |

| 6 x 6 x 6 | -40.926471 | 108 | 0.0001 |

| 7 x 7 x 7 | -40.926475 | 196 | 0.0001 |

| 8 x 8 x 8 | -40.926478 | 256 | 0.0001 |

| 9 x 9 x 9 | -40.926479 | 405 | 0.0001 |

| 10 x 10 x 10 | -40.926480 | 500 | 0.00001 |

| 11 x 11 x 11 | -40.926481 | 726 | 0.00001 |

| 12 x 12 x 12 | -40.926481 | 864 | 0.00001 |

| 16 x 16 x 16 | -40.926482 | 2048 | N/A |

| 24 x 24 x 24 | -40.926483 | 6912 | N/A |

| 48 x 48 x 48 | -40.926483 | 55296 | N/A |

Shown in Table 1 are the free energy values determined for varying grid sizes. The accuracy of the calculation is also shown, along with the number of k points that were actually sampled. An interesting observation is that the number of k points actually sampled is less that one would expect for the given grid size. For example, in a 2 x 2 x 2 grid of k points, one would expect 8 k points to be sampled. In actuality, only 4 k points are sampled. This comes from the idea of Monkhorst-Pack grids.4 These are tools that crystallographers and computational chemists use when working in reciprocal space. Due to the highly symmetrical nature of the MgO conventional cell, some of the k points specified in the grid become redundant via symmetry. As a result, the computational expense of these calculations is dramatically reduced. The optimal grid size was, again, found to be 24 x 24 x 24. This is a large enough grid size to approximate an infinite grid size, while still maintaining a reasonable computational time. A further increase to a grid size of 48 x 48 x 48 was shown to increase, drastically, the calculation time (on the order of minutes, compared to seconds for the 24 x 24 x 24 grid) with absolutely no improvement in the calculated value of free energy.

Thermal expansion of MgO

The expression below is used to determine the Helmholtz free energy in the quasi-harmonic oscillator. The first term on the right hand side is the zero point energy. The second term gives the energy within a harmonic approximation. The final term is the vibrational entropic contribution to the free energy. denotes the frequency of a vibration, is temperature, and is Boltzmann's constant.

Figure 8 shows that as temperature increases, the Helmholtz Free Energy increases in magnitude. This can be rationalised by considering the third term in the expression above for the Helmholtz Free Energy. This is a partition function which is related to the entropic contribution to the free energy. As the temperature increases from 0 to 1500K, thermal population of vibrational modes becomes nonzero. That is to say, vibrational modes (at higher energy than the zero point energy) begin to become populated by phonons due to the newly found thermal energy that comes from an increased temperature. This population of higher vibrational modes will follow a Boltzmann distribution. An increased multiplicity will lead to an increased vibrational entropy. Therefore, as the vibrational entropy increases, so does the entropic contribution to the Helmholtz Free Energy. Thus, the magnitude of the free energy increases with increasing temperature. The shape of this plot is in good agreement with plots in the literature.5

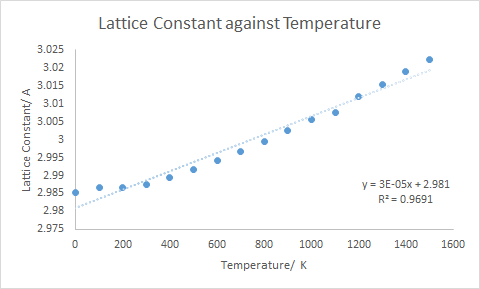

Figure 10 shows how the lattice parameter of the primitive MgO cell varies with temperature. The lattice parameter increases with increasing temperature. This comes back to the previous discussion of the quasi-harmonic approximation. Remember that this model allows the equilibrium bond distance to increase with increasing temperature. As the temperature increases, the potential energy of the system will rise up the wall of the parabola, and then the new equilibrium bond distance is determined. The new parabola is them expanded around this new distance. As the temperature increases further, this will occur again and again. Thus, the bond distance between any pair of adjacent atoms will increase with the temperature increase, the cumulative effect of which leads to an increase in lattice parameter.

The expression below relates the thermal expansion coefficient, to the change in volume with temperature, at constant pressure.

Examining the gradient of the plot in Figure 10, and using an initial length of 2.985 A, the following expression for the one dimensional expansion coefficient is obtained:

Then considering that this expansion occurs in all 3 directions:

This is in reasonable agreement with the literature value of x, which was recorded at a temperature of 300 K.5

If this system was acting under an exactly harmonic potential, the increase in temperature would not lead to an increase in the equilibrium bond length. It is likely that the solid will still expand, however. The vibrational modes at higher temperatures will clearly be of higher energy. The extent of vibration will increase with increasing temperature, and lead to an expansion of the solid. Under the quasi-harmonic approximation, the expansion can be explained in terms of the larger bond lengths around which each successive parabola is centred.

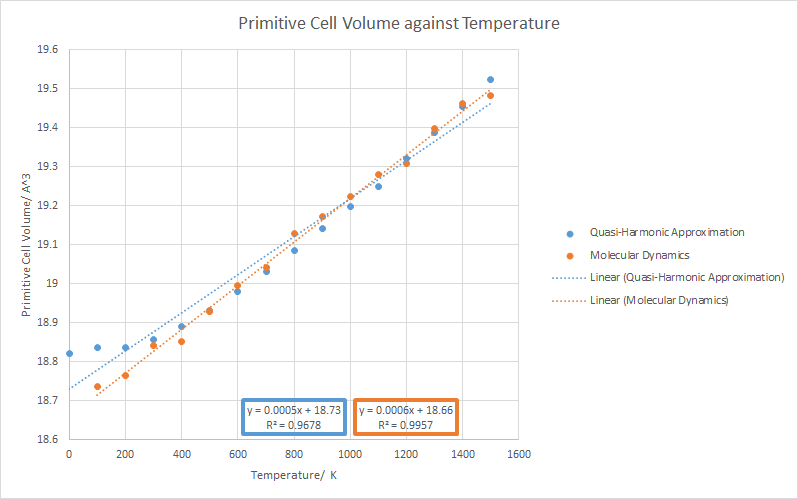

Molecular Dynamics

Using the same expression for the thermal expansion coefficient, and taking the gradient of the MD plot from Figure 11, along with an initial cell volume of 18.74 A3, an expansion coefficient of x. This value is slightly larger than the value predicted under the quasi-harmonic approximation. The discussion must return to the comparison of potentials used within these two methods. The molecular dynamics approach uses a Lennard-Jones potential to describe the interaction between adjacent atoms. This potential provides the all important dissociation treatment. At higher temperatures, the equilibrium bond distance increases - this has already been established. Under the molecular dynamics treatment, at high bond lengths, the adjacent atoms may become dissociated. These dissociations that occur throughout the lattice lead to the increased expansion coefficient when compared to the quasi-harmonic approximation. To conclude, both models account for the increase in cell volume at higher temperatures. The MD simulation allows dissociation to occur, whereas the QHA approach does not. The dissociation allowed under MD accounts for the larger value of the thermal expansion coefficient. It should also be mentioned that both of these models will lead to an increase in cell volume at high temperatures, due to the increase in vibrational wavelength leading to an increase in the lattice parameter (along each cardinal direction).

The optimal shrinking factor to approximate an infinite cell and thereby provide an accurate value of free energy was found to be 24. This was the grid size for k points in a single MgO conventional cell. In MD simulations, using a single cell would be pointless, and no useful information would be obtained. Drawing an analogy to the number of unit cells required for an accurate MD simulation - using 24 formula units should be acceptable. This corresponds to 24 primitive cells, or 6 conventional cells of MgO. Noting that 24 can be factorised as 2 x 2 x 2 x 3, this returns to the idea of folding within reciprocal space. The unit cell contains two different atoms to begin with, so it is folded, leading to 2 branches (for a one dimensional chain). Next, the direct space unit cell is doubled three times, leading to a further 3 folds. These folds are equivalent to halving each cell in reciprocal space, therefore doubling the number of branches in the dispersion relation. So far, there are 16 branches in the dispersion. Now, the final step is to triple the new cell size in direct space - therefore splitting the cell in reciprocal space into thirds. This folding process is different from the one for doubling the cell size, but is still similar. This folding leads to 48 branches. Now, since there are 3 possible directions, there will be a total of 144 branches in the dispersion relation, along with 24 pairs of degenerate levels at the centre of the Brillouin Zone. This should provide a sufficient size for MD simulations.

Conclusion

The dispersion relation was computed at 50 k point along conventional symmetry point paths in the fcc Brillouin Zone. The properties of this curve were discussed, and an attempt was made to rationalise them using physical bases. A theoretical background was provided to try and understand the origin of branches in the phonon dispersion.

The optimal shrinking factor in determining the DOS was found to be 24, based on comparisons with MgO DOS curves determined via neutron scattering experiments. The smoothness and continuity of the DOS curves were considered in determining the optimal shrinking factor, and the intensity of regions of DOS curves were related to the dispersion relation. A shrinking factor of 48 was shown to have negligible improvement on the measurement taken at a shrinking factor of 24, while having a drastically increased computational time.

The optimal shrinking factor in allowing a finite lattice to approximate an infinite lattice was also found to be 24. The value of free energy obtained at a shrinking factor of 24 was found to converge to the infinite value. Again, that obtained at a shrinking factor of 48 was found to be no better than that obtained at 24. Once more, this increased shrinking factor led to a massive increase in the computational expense.

These optimal grid sizes were speculated upon, and assumed to be acceptable for a similar binary oxide such as CaO. A zeolite would require a smaller shrinking factor to maintain resolution, due to the increased lattice parameter in direct space. A metal, such as lithium, would require a shrinking factor greater than 24 due to the delocalised nature of the electrons in a metallic species - which causes a very wide branch for metals.

The thermal expansion coefficient was determined under the quasi-harmonic and molecular dynamics models. The value was found to be larger in the molecular dynamics model. This is due to the use of a 12-6 potential to model interactions in the MD model, compared with the quasi-harmonic model. The 12-6 model allows dissociation to occur at the large bond distances caused by high temperature, whereas this is not considered in the quasi-harmonic model. The allowed dissociations were used as a rationale for the larger coefficient of thermal expansion found in the MD model.

The quasi-harmonic approximation breaks down at higher temperatures, but it, nevertheless, is a good model at lower temperatures. The molecular dynamics simulation provides a more "realistic" value for the thermal expansion coefficient (of course atoms may dissociate in reality) but it comes with the price of increased computational time. Thus, to conclude, the experimenter must consider whether the increased expense is worth it when trying to determine thermodynamic quantities of their system.

As further work, some more thermodynamic properties of MgO could be determined, such as elasticity and piezoelectric coefficients. Also, simulations could be carried out on CaO, faujasite and lithium in order to confirm or deny the speculations made about the generality of the optimal grid size.

References

[1] - B. G. Dick and A. W. Overhauser, Phys. Rev., 1958, 112, 90

[2] - J. D. Gale, J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans.,1997, 93(4), 629-637

[3] - Rossler and Blachnik; Semimagnetic Compounds, Springer, 1999

[4] - H. J. Monkhorst and J. D. Pack, Solid State Comm., 1976, 13, 5188

[5] - O. L. Anderson and K. Zu, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data., 1990, 16, 69

[6] - A. B. Organov, J. Geophys. Research, 2008, 113, B06204