Rep:Mod:DMS305

The Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of MgO - Daniel Spencer, 00736964

Abstract

In this investigation, the structure of MgO was simulated in order to investigate its free energy and thermal expansion, particularly through the modelling of phonon vibrations. This was achieved through the independent application of the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics, followed by comparison of the results obtained for the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO. It was found that the thermal expansion coefficient for MgO was 1.56 x 10-5 K-1, using the quasi-harmonic approximation, and 2.35 x 10-5 K-1, using molecular dynamics. Hence, it is evident that there is a significant discrepancy between the two methods which, when each is compared to literature, reveals that the use of the quasi-harmonic approximation in such calculations is the more accurate method.

Introduction

In this investigation, the aim is to computationally study the thermal properties of MgO under the quasi-harmonic approximation and using molecular dynamics. With regards to the quasi-harmonic approximation aspect of the experiment, the investigation is aimed at computing the vibrational energy levels, phonon dispersion and density of states for MgO in order to best model the system under this approximation and to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient. For molecular dynamics calculations, the aim is to simulate vibrations through the random motions of the atoms in the crystal and, using this method, calculate the thermal expansion coefficient. Finally, the coefficients obtained via each of these methods will be compared to each other, and to literature, in order to contrast the methods.

In order to conduct this investigation, it is important to consider the solid-state structure of MgO - this is a face-centred cubic crystal structure (at low pressure) of magnesium (or oxygen) atoms, with all of the octahedral holes in the structure occupied by oxygen (or magnesium) atoms, with the structure containing eight atoms, four magnesium and four oxygen atoms. At high pressures, MgO has a cubic crystal structure (of which CsCl is the synonymous crystal), with one atom type again occupying the octahedral holes[1]; however, in this experiment, the system will only be considered at a pressure of 0 GPa, hence the existence of this alternative structure can be disregarded. When making use of the quasi-harmonic approximation, the structure of MgO is considered in the form of the primitive unit cell (a rhombohedron in 3D space), which contains only two atoms; in contrast, molecular dynamics calculations consider a 2 x 2 x 2 supercell with respect to the conventional unit cell of MgO.

Also of importance for this investigation is thermal expansion, as this is fundamental to the calculations performed in this experiment. Thermal expansion is the process by which the atomic separation, and hence, cell volume, increases as the temperature increases. This volume increase is related to the thermal expansion coefficient, defined as

where α is the thermal expansion coefficient, V0 is the initial volume and the final term is the partial derivative of volume with respect to temperature at constant pressure. The higher the thermal expansion coefficient, the more the crystal will expand when heated. This equation will be used to calculate the coefficient both under the quasi-harmonic approximation and using molecular dynamics.

A discussion of the theory behind the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics, in relation to this investigation, is given in the corresponding sections below.

Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

The quasi-harmonic approximation is an extension of the harmonic approximation, with the intention of accounting for the thermal expansion that arises for anharmonic systems - this is neglected under the harmonic oscillator approximation due to the symmetry of the parabolic potential approximation.[2] Formally, this aspect of anharmonicity is introduced through the "renormalised" force constants and phonon frequencies. In general, the quasi-harmonic approximation treats each atomic separation as a separate harmonic oscillator, thus allowing for thermal expansion through bond extension at higher vibrational energy levels, whilst not fully accounting for bond dissociation. With regards to the quasi-harmonic approximation, it is important to note that it does not account for phonon-phonon interactions that can influence thermal properties.[2]

Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics considers the classical mechanics of the crystal structure and its constituent atoms through the use of Newton's second law, allowing evolution of the system. The velocities of the atoms are varied at random in order to approximate the desired temperature, then thermal properties of the system are calculated using time-averaged data for the atoms in the cell. For molecular dynamics, a time-step needs to be established for the sampling of the system's vibrations - in this investigation, the time-step to be used is 1 femtosecond. A significant difference to the computational set-up used for the quasi-harmonic approximation is in that the molecular dynamics computations require a larger cell; here, a 2 x 2 x 2 (with respect to the conventional unit cell) MgO supercell will be used - this allows for representation of all of the vibrations sampled using a 2 x 2 x 2 k-point grid.

Each method makes use of DLVisualize and the General Utility Lattice Program (GULP) to perform calculations on the respective models of MgO. Here, GULP is particularly useful due to its consideration of the symmetry of repeated three-dimensional structures, which greatly reduces the time required to complete a calculation by halving the number of k-points to be considered (this factor of a half is only applicable for even shrink factors).[3] DLVisualize provides a graphical user interface for the pictorial presentation of the results of calculations on the crystal structure, including the visualisation of the phonon vibrational modes of MgO. Use of these programs in conjunction with one another will allow for the investigation of the properties outlined, namely phonon dispersion, density of states, free energy and thermal expansion coefficient.

Investigating the Phonon Modes of MgO

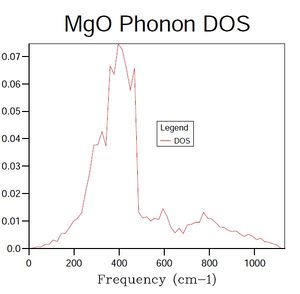

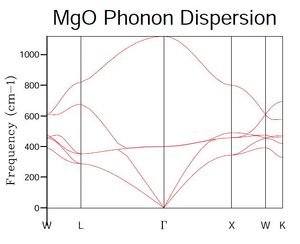

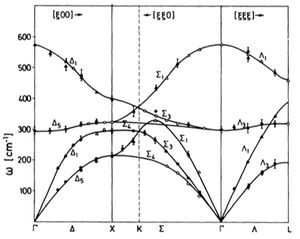

In order to investigate the phonon vibrational modes, the graph of phonon dispersion for MgO has first been calculated - this is presented in Figure 1. From Figure 1, it can be noted that there are six bands - these arise from the three Cartesian coordinates (degrees of freedom) and the two atoms present in the MgO primitive unit cell.

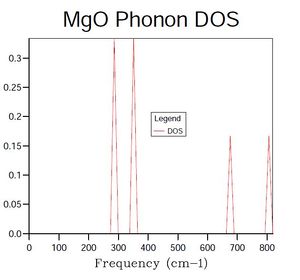

An examination of Figure 2, showing the density of states at a single point in k-space, reveals the presence of four vibrational modes. When considering this result with the phonon dispersion graph shown in Figure 1, it is evident that the single k-point selected must correspond to either point L (1/2, 1/2, 1/2) or X (1/2, 0, 1/2), where coordinates are (kx, ky, kz). However, the frequencies of states in the density of states graph reveals that the single k-point selected using a 1 x 1 x 1 grid must be L, as X does not feature the vibrational mode at approximately 680 cm-1.

A consideration of Figures 1 and 2 in conjunction indicates that many of the vibrational modes suggested from the graph of phonon dispersion are not represented in the density of states graph for point L.

In evaluating the shrink factors in order to determine the optimum solution to modelling the infinite system, it is important to observe that for factors from 1 to 16, computing time is below one second; this increases rapidly upon use of shrink factors 32 and 64 as the simulation is calculating the phonon modes for 131,072 k-points (accounting for symmetry), in the case of a 64 x 64 x 64 grid.

A second important factor to consider is the improvement in the density of states graph that is obtained by doubling the shrink factor, as, through comparison with the computation times, an optimum balance between the two factors can be decided upon. Changes in the density of states graph can not only be examined visually to compare the 'smoothness' of the graphs, but also numerically, by contrasting the Helmholtz free energy, A, values calculated for the different shrink factors.

| Shrink factor | Computation time, s | Helmholtz free energy, A, eV | Change in Helmholtz free energy, ΔA, eV |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0025 | -40.903254 | |

| 2 | 0.0036 | -40.901109 | 0.002145 |

| 4 | 0.0107 | -40.900978 | 0.000131 |

| 8 | 0.0842 | -40.900972 | 0.000006 |

| 16 | 0.7778 | -40.900978 | -0.000006 |

| 32 | 11.5753 | -40.900978 | 0.000000 |

| 64 | 453.0835 | -40.900978 | 0.000000 |

Comparing the data regarding Helmholtz free energy presented in Table 1 (recorded at 1 K as no free energies are calculated at 0 K), it is evident that the value of A converges to -40.900978 eV (six decimal places are given here to indicate that convergence is not achieved by 8 x 8 x 8 using the values calculated - assuming no uncertainty in the computations, which will not be the case) by a shrink factor of 16. Given also that the 16 x 16 x 16 grid has the last computation time less than one second for those tested, it is clear that, numerically, the shrink factor of 16 is optimal for simulating the infinite k-point structure - the Helmholtz free energy has, by this point and to the accuracy of the computation, converged on the infinite k-point grid size value. To demonstrate the suitability of this factor for modelling the MgO system graphically, the phonon density of states curve for this grid size can be considered - this is presented in Figure 3, alongside the graph for the 64 x 64 x 64 grid. In comparing the two, it is evident that there is added 'smoothness' to the curve when making use of a shrink factor of 64; however, the computation time of 7.5514 min (compared to 0.7778 s for 16) suggests that the benefits are unlikely to outweigh the large increase in computation time. Hence, for the purposes of modelling the infinite k-points for MgO in this investigation, the shrink factor of 16 will be used.

Whilst it could be argued that a shrink factor of 8 provides a reasonable approximation of the density of states for an infinite number of k-points, the additional computation time required for 16 is not large enough to discourage its use in further calculations.

In terms of a general analysis of the density of states graphs produced for different shrink factors, it is clear from those presented in Figures 2-4 that, as the factor is increased, the graph tends towards a smooth curve - this would be expected due to the connection between the density of states and the phonon dispersion graph, shown in Figure 1. This connection arises from the fact that the density of states curve represents an averaged summation of the vibrational modes shown in the phonon dispersion graph.

Considering further systems using this model

In examining the ability to generalise the conclusion regarding optimum grid size for MgO (found to be 16 x 16 x 16), an important class of compounds to consider is that of the comparable metal oxides (those with the face-centred cubic structure). Of these, calcium oxide, CaO, is the most easily comparable due to it being the oxide of a group 2 metal, like MgO. Intuitively, chemical and structural similarities suggest that the same grid size is likely to be efficient in modelling the density of states curve for an infinite number of k-points; this theory is further supported by a comparison of phonon dispersion curves and density of states curves, which reveals only small differences between the two.[4][5][6][7]. To highlight this comparison, Figure 5 presents the CaO phonon dispersion curve.

A second extension of this optimum grid size to consider is its application to a Zeolite, such as faujasite. Faujasite has a 'sodalite unit' structure consisting of 24 Si, 24 Al and 36 O atoms, with Na atoms positioned within this framework; each unit cell of sodium faujasite contains Na57Si135Al57O384.[8] Given the large number of atoms present in a unit cell, and hence, the large cell size, it would be expected that accurately modelling the infinite k-point density of states graph would require substantially fewer k-points than for MgO, due to the reciprocal space of the grid. This arises because maintaining the same density of k-points as for MgO requires a smaller shrink factor as the unit cell of faujasite will be smaller in this reciprocal space.

A final further example to consider is that of a pure metal, such as lithium. In general, metal systems require a greater number of k-points to model for an infinite number of k-points than for insulators, of which MgO is an example, most likely as a consequence of the multiple bands in the phonon dispersion graph of conductors.[9] Hence, it can be concluded that the optimum grid size for metals, such as lithium, is likely to be larger than that for MgO.

Computing the Free Energy of MgO Under the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

As demonstrated previously, the Helmholtz free energy of the MgO system can be calculated at different shrink factors in order to examine its variance with grid size, allowing a consideration of its accuracy in relation to the infinite grid of k-points. Here, these data will be considered at a temperature of 300 K, presented in Table 2.

| Shrink factor | Computation time, s | Helmholtz free energy, A, eV | Change in Helmholtz free energy, ΔA, eV | A(64) - A(x), eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0025 | -40.930301 | - | 0.003818 |

| 2 | 0.0034 | -40.926609 | 0.003692 | 0.000126 |

| 3 | 0.0077 | -40.926432 | 0.000177 | -0.000051 |

| 4 | 0.0107 | -40.926450 | -0.000018 | -0.000033 |

| 5 | 0.0252 | -40.926463 | -0.000013 | -0.000020 |

| 6 | 0.0354 | -40.926471 | -0.000008 | -0.000012 |

| 7 | 0.0609 | -40.926475 | -0.000004 | -0.000008 |

| 8 | 0.0832 | -40.926478 | -0.000003 | -0.000005 |

| 16 | 0.7624 | -40.926482 | -0.000004 | -0.000001 |

| 32 | 11.5938 | -40.926483 | -0.000001 | 0.000000 |

| 64 | 451.1722 | -40.926483 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

From the data in Table 2, it is evident that as the shrink factor is increased, the Helmholtz free energy converges towards the value for a infinite grid of k-points, as indicated by the ΔA values tending towards zero - by the time a 64 x 64 x 64 grid is used, there are minimal changes in the free energy, to the accuracy of the computational simulation. To further examine this, the 128 shrink factor could be used, although this would require an extremely large computation time (extrapolation of computational times based on seconds per k-point for the 64 case suggest that this time would be greater than one hour). Such additional computations may reveal some oscillation around the infinite k-point value for the Helmholtz free energy, providing further information about the system.

Using the data for ΔA and A(64)-A(x) (which compares each value to a 'reference' value - that at a shrink factor of 64), it is possible to ascertain the required grid size to achieve accuracy in the free energy value to different levels. From the data presented in Table 2, it is clear that for accuracy to 1 meV, the minimum required grid size of k-points must be 2, as the ΔA = A(3)-A(2) is less than 1 meV, as is A(64)-A(2). Hence, a shrink factor of 2 yields a Helmholtz free energy which is precise to 1 meV. To 0.5 meV, the required shrink factor must also be 2, using the same rationale. Finally, to an accuracy of 0.1 meV, a shrink factor of 3 must be used, as A(4)-A(3) and A(64)-A(3) are less than 0.1 meV - 3 is the smallest shrink factor for which this is the case.

Considering further systems using this model

The k-point grid size requirement for the accurate calculation of the free energy for different systems will be as discussed in the previous section. Hence, similar oxides, such as CaO, will require a similar grid size to that for MgO; Zeolites, such as faujasite, will require a small grid size than MgO; metals, such as lithium, will require a larger grid size.

Investigating the Thermal Expansion of MgO Using the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

Table 3 gives the data required for the calculation of the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO, measured using a shrink factor of 16, as decided upon in the investigation of the phonon modes of MgO.

| Temperature, K | Free energy, eV | Free energy, kJ (mol unit cells)-1 | Optimal lattice constant, Å | Cell volume, Å3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -40.9019 | -3946.4087 | 2.9866 | 18.8365 |

| 100 | -40.9024 | -3946.4582 | 2.9866 | 18.8365 |

| 200 | -40.9094 | -3947.1295 | 2.9876 | 18.8562 |

| 300 | -40.9281 | -3948.9383 | 2.9894 | 18.8900 |

| 400 | -40.9586 | -3951.8782 | 2.9916 | 18.9325 |

| 500 | -40.9994 | -3955.8188 | 2.9941 | 18.9801 |

| 600 | -41.0493 | -3960.6314 | 2.9968 | 19.0312 |

| 700 | -41.1071 | -3966.2085 | 2.9996 | 19.0851 |

| 800 | -41.1719 | -3972.4581 | 3.0026 | 19.1413 |

| 900 | -41.2430 | -3979.3207 | 3.0056 | 19.1996 |

| 1000 | -41.3198 | -3986.7336 | 3.0088 | 19.2600 |

| 2000 | -42.3237 | -4083.5871 | 3.0470 | 20.0030 |

| 2800 | -43.3536 | -4182.9552 | 3.0993 | 21.0501 |

| 2900 | -43.4948 | -4196.5816 | 3.1126 | 21.3226 |

| 3000 | - | - | - | - |

In the data presented, it is important to notice that for a temperature of 3000 K, no data are reported - this is a consequence of an error when performing the calculation, "probably due to unphysical cell dimensions". Evidence for this can be found in the log file for the computation, which revealed that the system was using lattice parameters of a = 2.5149 Å, b = 8.2900 Å and c = 4.0280 Å. These non-equal lattice parameters indicate that the crystal is likely undergoing a phase change (melting) at this temperature; however, the literature value for the melting point, whilst controversial, is typically around 3100 K, as reported both practically and from molecular dynamics calculations for zero pressure.[10][11] Given that the quasi-harmonic calculations can be performed up to around 2950 K, but not at 3000 K, it is easy to conclude that the melting point of MgO is, according to this experiment, in this range. In this temperature region, phonon-phonon interactions would be expected to occur; however, the quasi-harmonic approximation does not account for these.

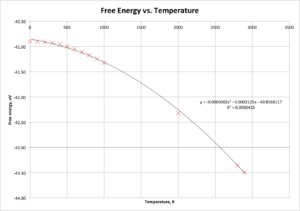

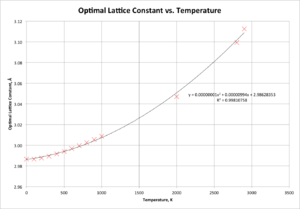

Figure 6 presents a graph of free energy versus temperature, whilst Figure 7 presents optimal lattice constant against temperature. In each case, it is clear that the data have best-fit lines of a quadratic (second order polynomial) nature, indicating that both free energy and the lattice constant have significant dependencies on the temperature at which the calculation is performed. In both cases, the graphs support the expectations that as the temperature increases, the cell grows larger (lattice constant increases - thermal expansion) and the magnitude of the free energy increases.

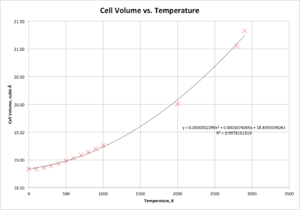

In order to use the data collected to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient, α, for MgO, a graph of cell volume against temperature is the most useful, as it directly corresponds with the equation for α:

A graph of cell volume versus temperature is presented in Figure 8.

To simplify the calculation of the thermal expansion coefficient, and to obtain a temperature-independent result, this graph can be approximated as a straight line (rather than the better fitting quadratic) for temperatures between 500 K and 2000 K. Hence, this allows the equation for α containing a partial derivate to be simplified to:

and therefore, only the gradient of this approximated linear fit is required to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient. This calculation, using a gradient of 0.0006922 Å3 K-1 and a V0 of 18.9801 Å3 (the initial cell volume at 500 K) yields a value for α of 3.65 x 10-5 K-1. Comparison of this value to literature, for which a typical value of α is 1.08 x 10-5 K-1 at 273 K,[12] shows that there is a substantial degree of inaccuracy in making this linear approximation.

If this linear approximation is not made, a temperature-dependent equation for the thermal expansion coefficient is obtained. Using the differential of the second order polynomial fit as:

the equation for α becomes:

To enable a comparison to the literature value listed previously, this equation can be evaluated at 273 K, giving a value for the thermal expansion coefficient of 1.56 x 10-5 K-1. It is immediately evident that this value is significantly closer to that reported in the literature and hence, the inaccuracies in the linear approximation are highlighted further.

Further Considerations

Thermal expansion arises as a consequence of the anharmonicity of the potential energy for a collection of atoms. This is because as a group of atoms is thermally excited, they 'move' to occupy a higher vibrational energy level in the Lennard-Jones potential diagram, meaning that the amplitude of oscillations around the equilibrium atomic distance is larger, resulting in the equilibrium separation moving to a larger distance.[13] Hence, thermal expansion occurs as a consequence of the increased average separation of the atoms, according to the vibrational energy level structure of the anharmonic oscillator. In contrast, when using a harmonic approximation (and hence, harmonic potential) for a diatomic molecule, the bond length is expected to remain constant with temperature, as the parabola approximation does not have the asymmetry of the Lennard-Jones potential - an increase in vibrational energy level does not change the equilibrium bond length.[13] When using the quasi-harmonic approximation for MgO, the anharmonicity is accounted for by modelling the system as a harmonic oscillator at each atomic separation, overall accounting for the asymmetry of the Lennard-Jones; hence, the average atomic separation will increase with temperature.

A second consideration is that of the behaviour of the model as the temperature approaches Tmelt for MgO. As this occurs, the phonon modes will not be a good representation of the actual movement of the atoms due to the occurrence of phonon-phonon interactions that become evident at such temperatures.[14][15] As a consequence of this, calculations on phonon modes made using the quasi-harmonic approximation at temperatures approximately in the range 2000 K to 3000 K are likely to be poorly representative of the actual atomic motions.

Investigating the Thermal Expansion of MgO Using Molecular Dynamics

In order to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO using a molecular dynamics calculation, the data for temperature and cell volume in Table 4 were collected. From the calculation, an average cell volume for a 2 x 2 x 2 repetition of MgO conventional unit cells is obtained - a volume per cell is calculated through division by 8 (the number of unit cells used to form the supercell) to get the conventional unit cell volume.

| Temperature, K | Average temperature, K | Average cell volume, Å3 | Volume per cell, Å3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 50.0018 | 598.6478 | 74.8310 |

| 100 | 100.0557 | 599.4666 | 74.9333 |

| 200 | 199.9967 | 600.5212 | 75.0652 |

| 300 | 300.3229 | 602.9699 | 75.3712 |

| 400 | 399.8201 | 603.8919 | 75.4865 |

| 500 | 499.4370 | 605.0708 | 75.6339 |

| 600 | 599.7163 | 607.9302 | 75.9913 |

| 700 | 699.9158 | 609.7082 | 76.2135 |

| 800 | 799.7732 | 611.1357 | 76.3920 |

| 900 | 899.6130 | 613.4117 | 76.6765 |

| 1000 | 1000.7640 | 614.5954 | 76.8244 |

| 1500 | 1499.4002 | 624.9271 | 78.1159 |

| 2000 | 1997.6066 | 631.5636 | 78.9455 |

| 2500 | 2498.1625 | 648.0163 | 81.0020 |

| 3000 | 2999.4988 | 661.7806 | 82.7226 |

| 3500 | 3501.6282 | 678.0989 | 84.7624 |

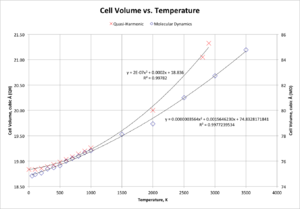

In order to allow for a comparison of this technique with that of the quasi-harmonic approximation, Figure 9 presents a graph of cell volume against temperature for data from the quasi-harmonic calculation, alongside molecular dynamics data. Note that to present both sets of data on the same graph, the molecular dynamics data is presented using a different scale; however, the equations for the trend-lines are directly comparable.

As for the quasi-harmonic approximation calculation, it is simple to approximate a region of the molecular dynamics graph as linear - here, the region 50 K to 1000 K has been selected. This gives a ΔV/ΔT of 0.002152 Å3 K-1, with a V0 of 74.8310 Å3. Hence, using the formula for the thermal expansion coefficient, α can be found to be 2.88 x 10-5 K-1. A comparison to the literature value of 1.08 x 10-5 K-1 shows that whilst there is a large difference between the two, this difference is smaller than for the quasi-harmonic value using the linear approximation.[12] Hence, the molecular dynamics cell volume versus temperature curve is much better approximated as a linear fit than that for the quasi-harmonic approximation. Using a quadratic best-fit line,

At 273 K, this equation for α gives a value of 2.35 x 10-5 K-1 which, when compared to literature, is evidently more accurate than the linear approximation method.

To compare the quasi-harmonic method with the molecular dynamics method, the values for the thermal expansion coefficient at 273 K (using the quadratic trend-line) will be considered: 1.56 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic method, 2.35 x 10-5 K-1 for the molecular dynamics method. An examination of these figures, when compared to literature, indicates that the quasi-harmonic calculation provides a substantially more accurate result. The two methods used produce differing results as a consequence of their design - molecular dynamics is a classical mechanics method and does not account for any phase change (data can be collected above 3000 K, albeit with some cell distortion, such as empty regions), whilst the quasi-harmonic approximation does acknowledge the loss of the crystalline structure (calculations can no longer be performed). Intuitively, the difference between α calculated for the quasi-harmonic approximation and that calculated for molecular dynamics is linearly dependent on temperature, using the equations derived in the respective sections (from a second order best-fit line). The equation of this dependence is easily found to be:where Δα refers to αQH - αMD.

Further Speculation

A valid consideration following efforts to identify the required k-space grid size required to accurately the free energy of the MgO system under the quasi-harmonic approximation is the method for this process using molecular dynamics. In this experiment, a 2 x 2 x 2 repetition of MgO conventional unit cells was used - giving 64 atoms in total. For quasi-harmonic, a primitive unit cell was considered, and it was found that a 3 x 3 x 3 k-point grid size provided free energy accurate to 0.1 meV. Assuming that the same number of k-points is required to obtain a free energy to this accuracy using molecular dynamics, and knowing that a 2 x 2 x 2 MgO supercell can represent all of the vibrations of a 2 x 2 x 2 k-point grid, it can be deduced that a 3 x 3 x 3 MgO supercell, with respect to the conventional unit cell, will likely provide a free energy accurate to 0.1 meV.

At high temperatures, approaching and at the melting point of MgO, the two methods behave quite differently. In the case of the quasi-harmonic approximation, calculations can no longer be performed above approximately 2950 K - the system accounts for the loss of the crystalline structure. For molecular dynamics, no such barrier is observed - calculations can be performed well above the melting point, as evidenced by the collection of data at 3500 K, although distortion of the cell is observed. Up to the melting point of MgO, the quasi-harmonic approximation calculations show a quadratic increase in cell volume, whilst molecular dynamics calculations show this quadratic increase to continue above this point. The quasi-harmonic approximation will also involve an additional error at these high temperatures, due to not accounting for the phonon-phonon interactions that will occur.

Conclusion and Evaluation

In this investigation, the MgO crystal system was examined through the independent application of the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics. Considering the phonon dispersion and density of states graphs produced under the quasi-harmonic approximation, it was found that in order to model the density of states at infinite k-points, a shrink factor of 16 was required. In computing the free energy of MgO, again using the quasi-harmonic approximation, it was found that, to an accuracy of 0.1 meV, a k-point grid size of at least 3 x 3 x 3 was required.

To calculate the thermal expansion coefficient, both the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics were used - the quasi-harmonic approximation uses a quantum mechanics approach to the calculation through treatment of atomic separations as a collection of harmonic oscillators, whilst molecular dynamics takes a classical mechanics approach, based on Newton's second law. For the calculations of the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO, the values obtained with a linear approximation were 3.65 x 10-5 K-1 and 2.88 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic approximation and molecular dynamics respectively. Without the use of this linear approximation, the corresponding values were 1.56 x 10-5 K-1 and 2.35 x 10-5 K-1 at 273 K. A comparison of these data with literature indicated that, whilst the linear approximation was better for molecular dynamics, the quasi-harmonic calculation of the thermal expansion coefficient was likely to be more accurate than that for molecular dynamics. Hence, it can be concluded that the use of the quasi-harmonic approximation in such calculations is the better solution.

A significant improvement to the experiment could be made through the implementation of a different method - the pseudo-harmonic approximation, which accounts for both thermal expansion and phonon-phonon interactions.[2] In this investigation, the quasi-harmonic approximation accounts only for the thermal expansion that arises from anharmonicity, not for these interactions; hence, the data collected at high temperatures, but below the melting point of MgO, could be significantly improved through the application of this pseudo-harmonic approximation.

References

- ↑ B. B. Karki, L. Stixrude, S. J. Clark, M. C. Warren, G. J. Ackland, J. Crain, Am. Mineral., 1997, 82, 51-60

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 G. P. Srivastava, The Physics of Phonons, Adam Hilger (IOP Publishing Ltd), Bristol, 1990, 113-119

- ↑ J. D. Gale, J. Chem. Soc., 1997, 93, 629-637. DOI: 10.1039/A606455H

- ↑ H. Bilz, W. Kress, Phonon Dispersion Relations in Insulators, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1979, 50-51

- ↑ M. J. L. Sangster, G. Peckham, D. H. Saunderson, J. Phys. C, 1970, 3, 1026-1036

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 K. H. Rieder, B. A. Weinstein, M. Cardona, H. Bilz, Phys. Rev. B, 1973, 8, 4780-4786

- ↑ D. H. Sanderson, G. Peckham, J. Phys. C, 1971, 4, 2009-2016

- ↑ G. R. Eulenberger, D. P. Shoemaker, J. G. Keil, J. Phys. Chem., 1967, 6, 1812-1819

- ↑ W. F. Schneider, 'Lecture 11: Electronic Structure in Periodic Systems', CBE 60547 Computational Chemistry, 4/1/2014, University of Notre Dame, 2014

- ↑ A. Ansary Yar, M. Montazerian, H. Abdizadeh, H. R. Baharvandi, J. Alloy. Compd., 2009, 484, 400-404

- ↑ L. Vocadlo, G. D. Price, Phys. Chem. Miner., 1996, 23, 42-49

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Crystran, http://www.crystran.co.uk/optical-materials/magnesium-oxide-mgo, accessed November 2014

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lecture Notes (no listed author), 'Chapter 19: Thermal Properties', MSE 2090 Introduction to Materials Science, University of Virginia. http://people.virginia.edu/~lz2n/mse209/Chapter19.pdf, accessed November 2014.

- ↑ Z. Wu, R. M. Wentzcovitch, Cornell University Library - An efficient method to calculate the anharmonicity free energy, 2006. http://arxiv.org/abs/cond-mat/0606745, accessed November 2014

- ↑ R. Wentzcovitch, 'VLab Tutorial - The Quasiharmonic Approximation', University of Minnesota. http://www.vlab.msi.umn.edu/events/download/vlab_lectures/renata/lecture2_1.pdf, accessed November 2014