Rep:Mod:DAAO inorg

Module 2: Bonding Analysis using Ab initio and Density Functional Techniques

Introduction

Computational chemistry can be great help to chemists. This branch of chemistry is particularly important when examining systems containing inorganic compounds and complexes as bonding tends not to be as ‘simple’ as in organic chemistry. Computational chemistry is advantageous as it allows us to explore the structure and bonding of such complexes without having to even step into a laboratory. Here, the benefits of using computational chemistry will be show through a series of exercises which include a study of BH3 and BCl3. This involves optimising the geometry of both molecules where the nuclei are in the optimum position for that electronic configuration by performing calculations using the program, Gaussian. [1] Vibrational analysis will also be carried out on the two molecules. There will be a deeper investigation of BH3 as its molecular orbitals are considered and natural bond orbital analysed. The cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 will be discussed with regards to their IR spectra and relative thermal stability after optimising their geometry. This report will then be concluded with a mini-project comparing four different lewis acid-base complexes of BF3 using the computational techniques acquired.

Taking the accuracy of the programs that are going to be used both frequencies and intensities are quoted to the nearest integer while bond distances and angles are noted to 0.001Å and 0.1⁰ respectively.

A Study of BH3

Optimising a Molecule of BH3

After having created a molecule of BH3 in GaussView3, all three B-H bond lengths were set to 1.5 Å and H-B-H angle of 120.0 ⁰. The geometry of this molecule was then optimised using Gaussian for the calculation. The method, basis set and calculation type were set as B3LYP, 3-21G and OPT (for optimisation) respectively. This basis set was chosen as although it has a low accuracy, calculations are quick. [1] The optimisation of BH3 gave the geometry shown below.

|

After optimisation, all B-H bonds are an equal length of 1.194 Å and each H-B-H angle remained 120.0⁰. This angle corresponds to a trigonal planar geometry. The calculated bond length agrees well with the value cited in the literature (1.20 Å).[2]

Looking at the calculation summary, one can find out easily the calculation type, basis set, point group and various other pieces of information regarding the calculation performed. The calculation summary for the BH3 optimisation is shown below.

D-space file: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:DOROTHY_BH3_OPT.LOG

It is possible to check whether the geometry of the BH3 molecule is optimised fully by looking at the ‘real’ text based .out file. It shows:

This shows that the forces are converged and small displacements do not change the energy of the molecule. It can therefore be said that the molecule has been fully optimised.

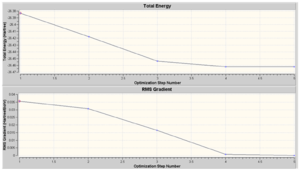

Using Gaussview the optimisation plot (i.e. optimisation step number vs total energy (Hartree) and RMS gradient (Hartree/ Bohr)) was obtained.

One can also obtain screenshots of the animation of the optimisation steps.

| Screenshot of Animation |  |

|

|

|

|

| B-H Bond length/ Å | 1.50 | 1.41 | 1.28 | 1.19 | 1.19 |

We can see from above that at the highest total energy the structure does not contain bonds. From this we must not conclude that the bonds do not exist but rather that the length of the bonds is longer than the greatest bond length pre-defined in the program. The H-B-H angle remains constant at 120 ⁰ (i.e. trigonal planar geometry) throughout optimisation. We can see that the last optimisation step has the lowest gradient. At this step the geometry has been fully optimised.

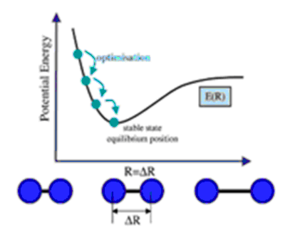

Let us now consider what is happening during an optimisation. The purpose of optimisation is to obtain the stable state equilibrium position of all the bonds in a molecule. The nuclei are positively charged, when they are become closer to each other this causes repulsion and the energy of the molecule to increase. If the nuclei are too far apart, the electron-nucleur attraction decreases. This means that the molecule dissociates and its energy increases. The stable state equilibrium position is obtained when net forces (such as nuclear-nuclear repulsion, nuclear-electron attraction or electron-electron interactions) are not acting on the molecule. At this point the slope of the potential energy surface equals zero. This equilibrium state is obtained by varying the coordinates of the nuclei and electrons and comparing the energy of the molecule until the lowest energy is achieved.[3]

Molecular Orbitals of BH3

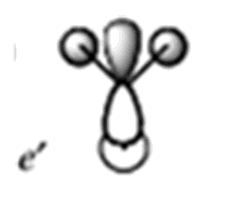

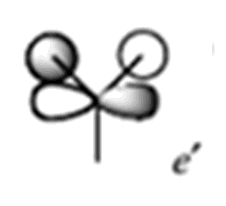

In this section, the results from the calculations performed to solve the electronic structure of BH3 and obtain its molecular orbitals (MOs). These computed MOs will then be compared to the MOs produced from MO diagrams.

Using the programs Gaussian and Gaussview 3, calculations were performed using the fully optimised geometry from the previous exercise of BH3, the basis set 3-21G, the additional keywords “pop=full” and “Full NBO” selected to obtain its MOs. The calculation summary is found below.

D-space file: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:DOROTHY_BH3_OPT_POP.LOG

We will now focus on the occupied and lowest energy unoccupied orbitals.

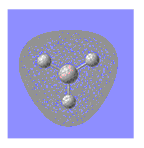

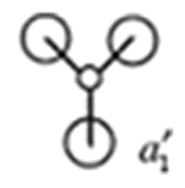

| MO | MO from Calculation | MO from Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) | Energy of Calulated MO/ a.u |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

n/a | - 6.730 |

| 2 |

|

|

- 0.517 |

| 3 |

|

|

- 0.356 |

| 4 |

|

|

- 0.356 |

| 5 |

|

|

- 0.074 |

| 6 |

|

|

0.191 |

| 7 |

|

|

0.188 |

| 8 |

|

|

0.188 |

From the above, we can see that the MOs from the calculations and those from the approximate MOs via the MO diagram agree well both in shape and relative energies for most of the orbitals. The occupied MOs 3 and 4 are degenerate in both cases as well as the unoccupied MOs 7 and 6. The main difference occurs with relative ordering of the higher energy unoccupied MOs 6, 7 and 8. In the qualitative MO diagram, MOs 7 and 8 are degenerate and higher in energy than MO 6 whereas the calculations show MO 6 to be higher in energy. This highlights the usefulness of the calculations. Qualitatively it is difficult to assess whether the s-s interaction will be stronger than the s-p interactions and therefore it is difficult to work out the correct relative ordering of these MOs. As the calculations show MO 6 to be the highest in energy we can conclude that the s-s interactions are greater than the s-p interactions. This highlights that qualitative MO theory is incredible useful method for generating MO diagrams when one is not able to use computational techniques or complete accuracy is not required.

From the MO diagrams, we can see that BH3 has a low energy LUMO. This means it can accept electrons from a lewis base and therefore is a lewis acid.

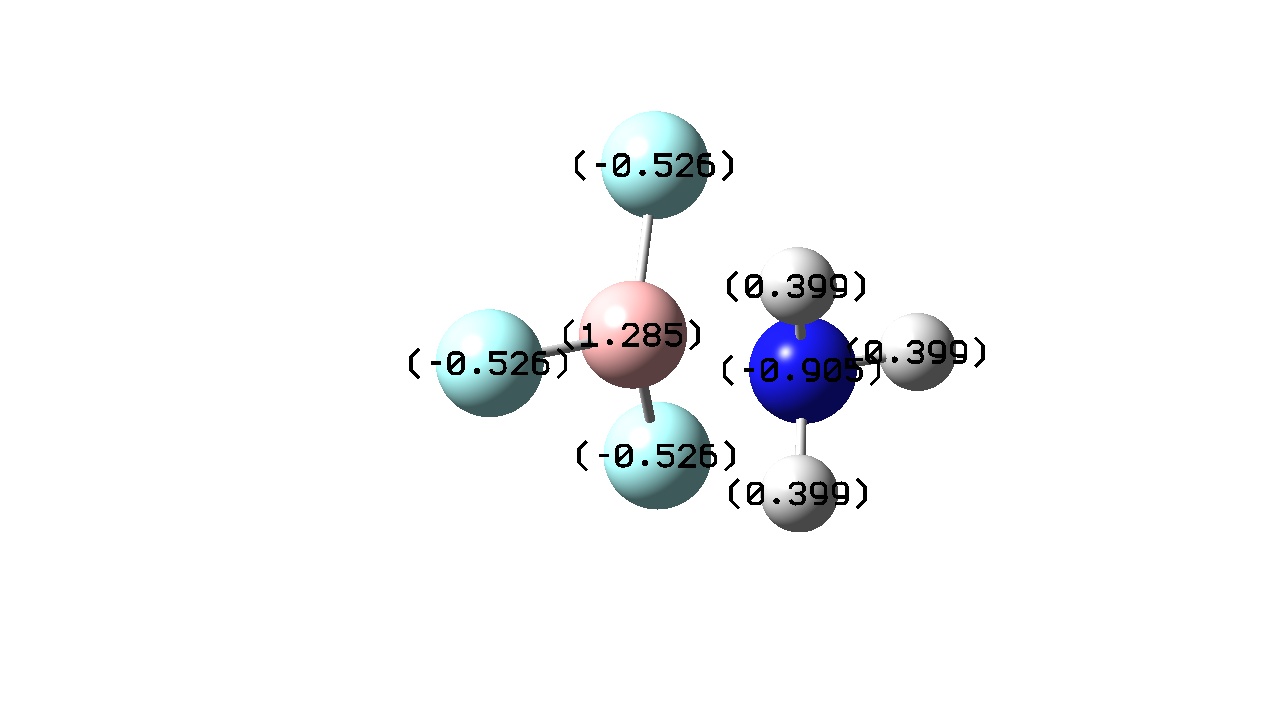

Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis of BH3

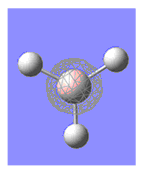

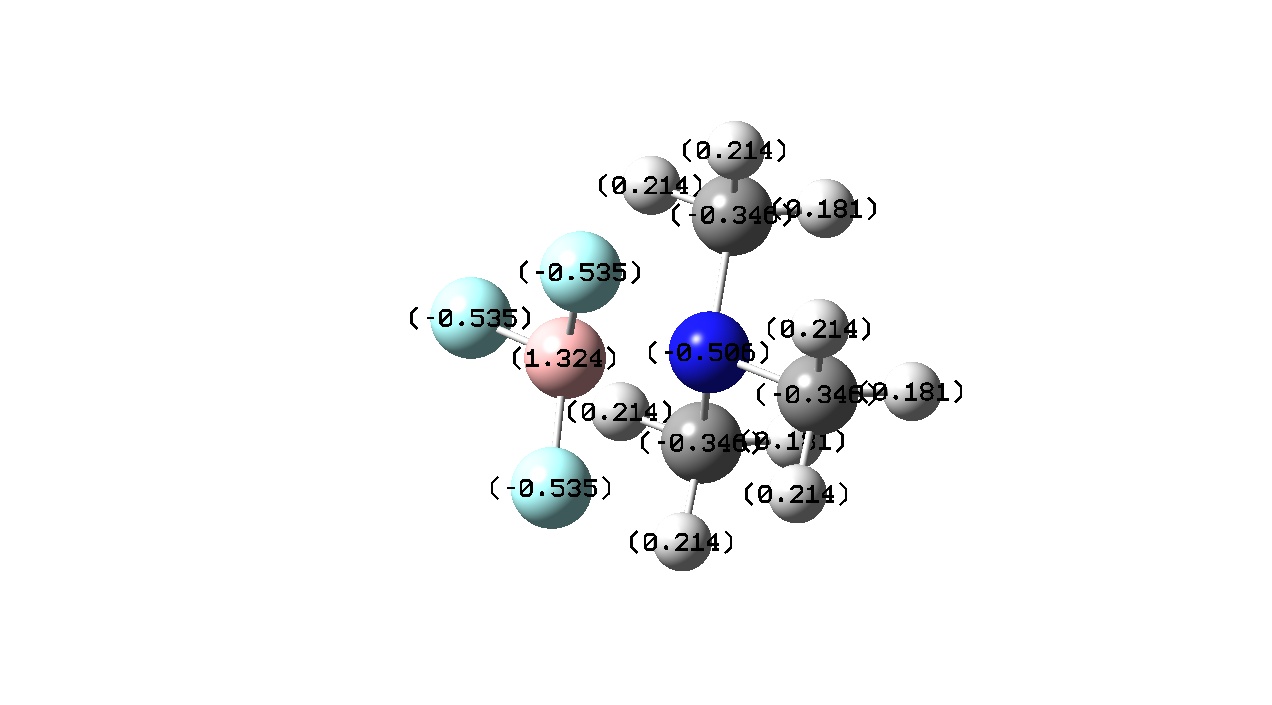

NBO analysis can be useful in indicating the charges on the individual atoms in a molecule. This can be seen below.

The Boron atom comes up as bright green in colour while the Hydrogen atoms are bright red. This indicates the Boron is positively charged while the Hydrogens are negatively charged. This is not surprising when one takes into account the electron deficiency of the Boron atom. This is also shown by the atoms charge number in C. All the Hydrogens are equally negatively charged confirming that they are all equivalent. Summing the atomic charges of the molecule confirms that it is neutral. This information can also be obtained from the ‘Summary of Natural Population Analysis’ from the .log file.

Further information about the orbitals of BH3 can be obtained from this .log file.

From the above, we can see that the Hydrogen orbital contributes 55.51 % to a B-H bond while the remaining 49.49 % comes from the Boron orbitals. The Boron has 3 sp2 hybrid orbitals as it has a hybridisation of 33.33 % s and 66.67 %p (i.e a 2:1 ratio of p character: s character). It is these hybridised orbitals which interact with the s atomic orbital of the hydrogen atoms (which have 100 % s-character). We can also see that the core 1s atomic orbital of Boron is not interacting with any of the hydrogen atoms.

To consider the empty p atomic orbital we must now consider the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO).

The ‘Natural Bond Orbitals (Summary)’ can provide insight into the lewis acid character of a molecule. The empty (i.e its occupancy is zero) p atomic orbital is natural bond orbital (NBO) 8. It has a negative energy and therefore as a low lying empty orbital it can accept electrons and act as a lewis acid. To find out which orbital is in fact NBO 8, we must now look at the section of the .log file entitled ‘NATURAL POPULATIONS: Natural atomic orbital occupancies’.

From this, we can see that NBO 8 is the natural atomic orbital (NAO) 8 and corresponds to the valence 2pz atomic orbital. We can also see that the valence 2px and 2py are partially filled.

From the section of the .log file entitled ‘Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis’, we also know that no mixing is occurring between various MOs. We would expect values of greater than 20 kcal/mol in the E(2) column if anything of interest was happening.

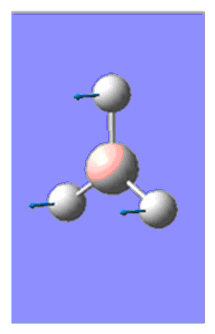

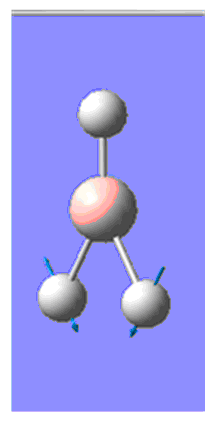

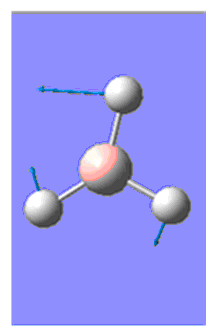

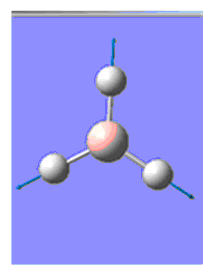

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

By carrying vibrational analysis, one can determine whether a fully optimised molecule of BH3 was indeed obtained. This analysis involved taking the second derivative of the potential energy surface and if the frequencies calculated are positive (i.e we have a minimum), we know that the molecule was fully optimised otherwise we would have obtained a transition state.

Again using the programs Gaussian and Gaussview3 and the supposed fully optimised geometry of the BH3 molecule, frequency calculations were performed using the b3lyp method, 3-21g basis set and the additional keywords:pop=(full,nbo).

D-space file: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:DOROTHY_BH3_FREQ.LOG

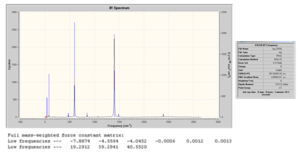

The six frequencies listed after low frequencies correspond to the motions of the centre of mass of the BH3 molecule. The largest low frequency is about 22 cm-1. This is smaller than the frequency of the first vibration (1145 cm-1) but greater than the ± 10 cm-1 normally required. This discrepancy is due to the low level method of the calculation.

None of frequencies are negative and it can be said the structure is fully optimised. The IR spectrum and analysis of the vibrations of BF3 are shown below.

Only three peaks are visible in the IR spectrum even though there are obviously six vibrations of the molecule. One explanation for this is that only the unsymmetrical vibrations (i.e vibrations causing the dipole moment of the molecule to be greater than zero) are IR active. This is the reason the peak at 2593 cm-1 corresponding to a symmetric stretch has an intensity of zero. Another reason for the lack of peaks is that vibrations number 2 and 3 and vibrations 5 and 6 absorb at approximately the same frequency and so without zooming in a lot, one is not able to see individual peaks.

A study of BCl3

Here, a larger basis set and a pseudo-potential will be used in calculations. Pseudo-potentials make calculations easier while using a larger basis set allows a better fit. Using a larger basis set means that calculations take longer, one must balance the length of the computation with the accuracy needed.

Optimising a Molecule of BCl3

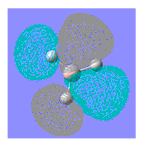

After creating a molecule of BCl3 in Gaussview 3.0, its symmetry was restricted to D3h and its tolerance changed from the default setting to very tight (0.0001). One would expect the ground state structure of BCl3 to have D3h symmetry as it has the following symmetry elements: E, 2C3, 3C’2, σh, 2S3 and 3σv. Here, the restriction on the symmetry is so that the calculation takes less time. The molecule was then optimised using Gaussian and the method B3LYP and the basis set Lan2MB. This basis set is of a higher level compared to the 3-21 G basis set used in the optimisation of the BH3 molecule. The calculation summary can be found below.

| Optimised Structure |  |

| jmol | |

| Optimised B-Cl Bond Distance/ Å | 1.87 (lit.)[5] 1.75 |

| Optimised Cl-B-Cl Bond Angle/ ⁰ | 120 |

D-space file: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:DAAO_BCL3_OPT.LOG

Just like the BH3 molecule, the BCl3 molecule is trigonal planar. The calculated B-Cl bond length is longer than the value cited in the literature. This may be due to using a medium level basis set. It an even larger basis set had been used in the calculations it is possible that a value closer to that stated in the literature would be obtained.

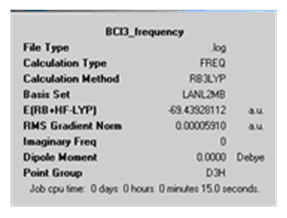

Vibrational Analysis of BCl3

It can be confirmed that the above structure of BCl3 is a minima by frequency analysis. As mentioned above, this involves taking the second derivative of the potential energy surface and then from the sign one can determine whether the structure has been fully optimised or if a transition state was obtained instead. The same method (B3LYP) and basis set (LAN12MB) as selected in the optimisation stage of this exercise were chosen for these calculations. This is important as it means that the energies are the same in both cases and therefore the results are comparable.

The calculation summary is shown below.

D-space file: https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:DAAO_BCL3_FREQ.LOG

The energy shown on the calculation summary for both the frequency analysis and the optimisation are the same up to six decimal places. This means that the frequency analysis was done on the right file. The summary also shows the calculation method, basis set, time taken for the calculation among other pieces of information.

Similar to the case above, in some structures Gaussview does not draw bonds where it is expected but one must not conclude that a bond therefore does not exist. The absence of a bond is due to the bond length exceeding a pre-defined parameter in the program which states the length of the longest bond. There are many different types of bonds including ionic and metallic. The bonding in BCl3 is covalent. A chemical bond can be described as the attractive force by which atoms in a molecule are held together. [6]

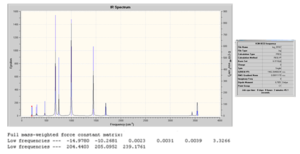

The IR spectrum of BCl3 is shown below.

From above, we can see that no negative frequencies were obtained from the calculations and so the structure of the BCl3 has been fully optimised. We can also see that by using a larger basis set the low frequencies are much closer to zero than in the case of BH3 above with the largest low frequency being about -9 cm-1. All the low frequencies are within ±10 cm-1 as is normally required.

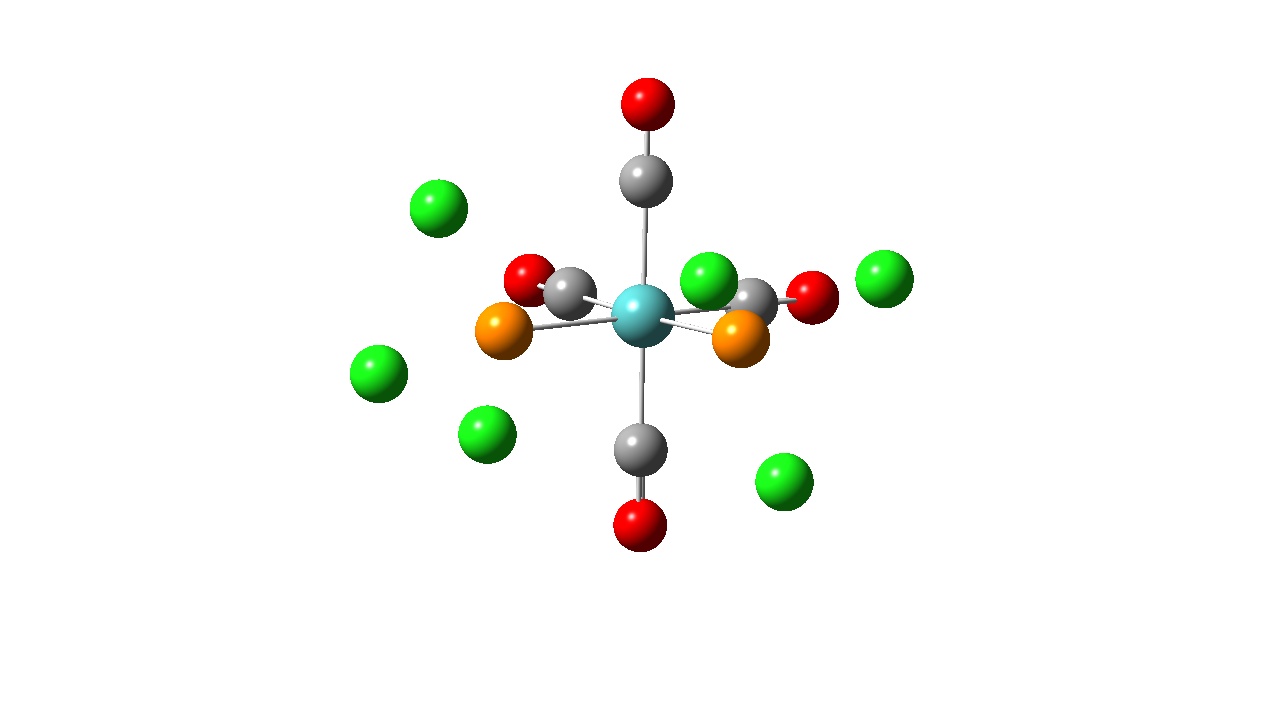

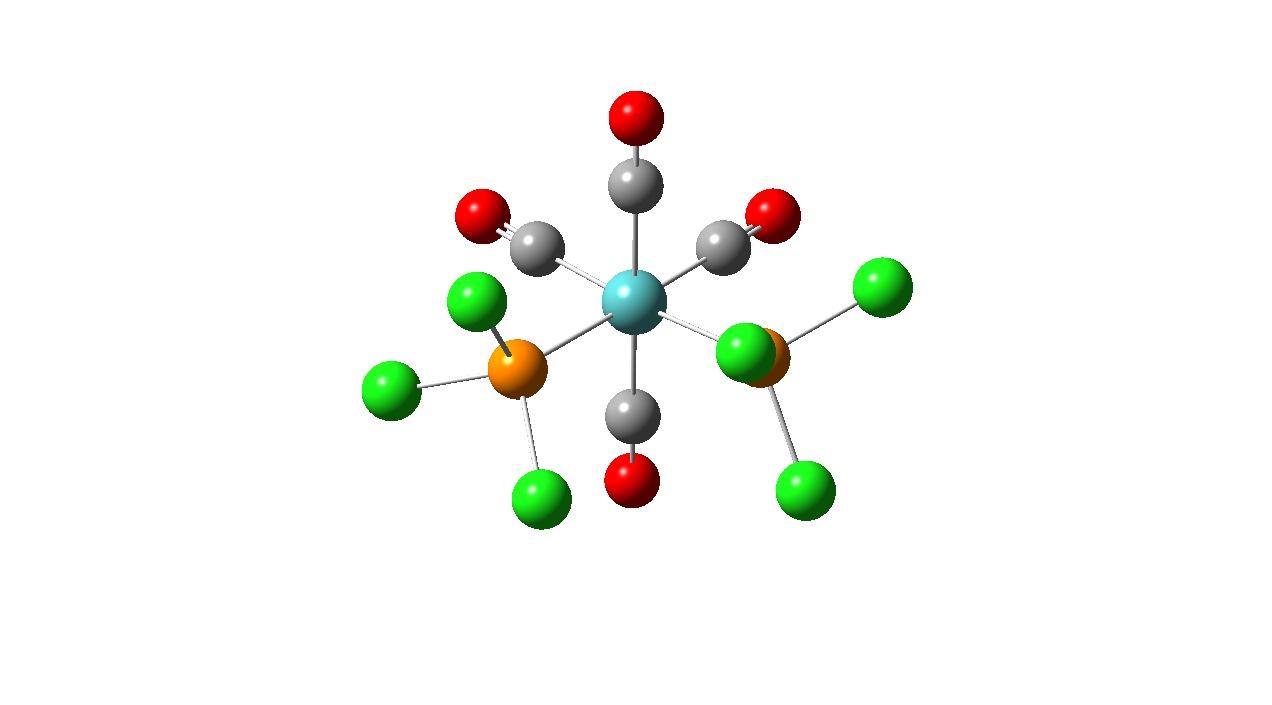

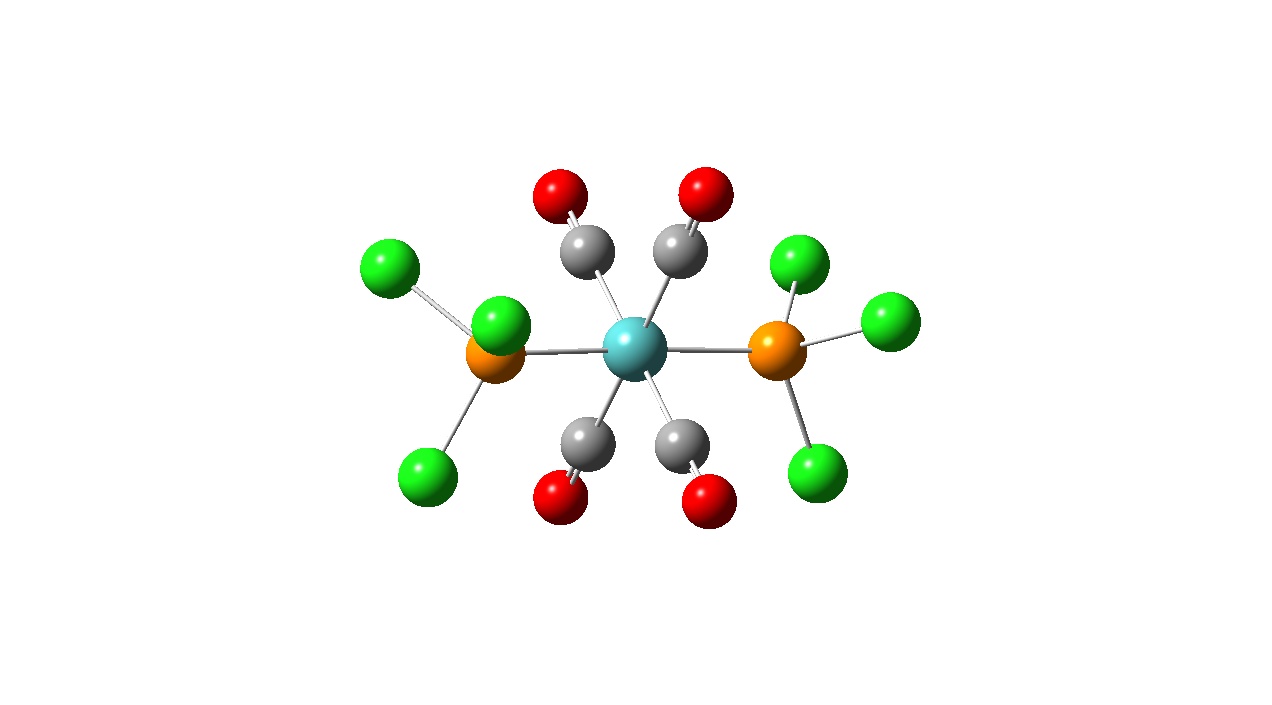

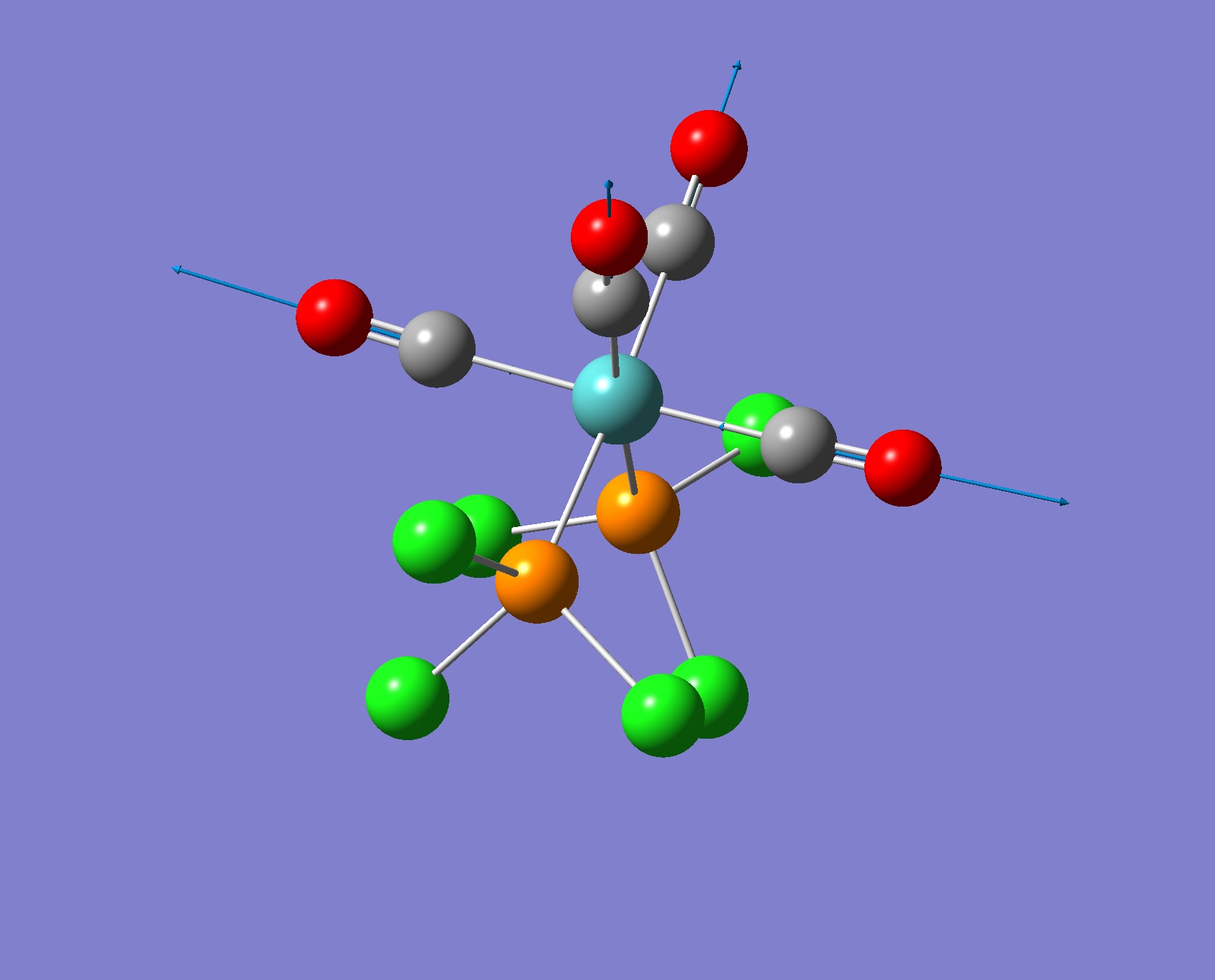

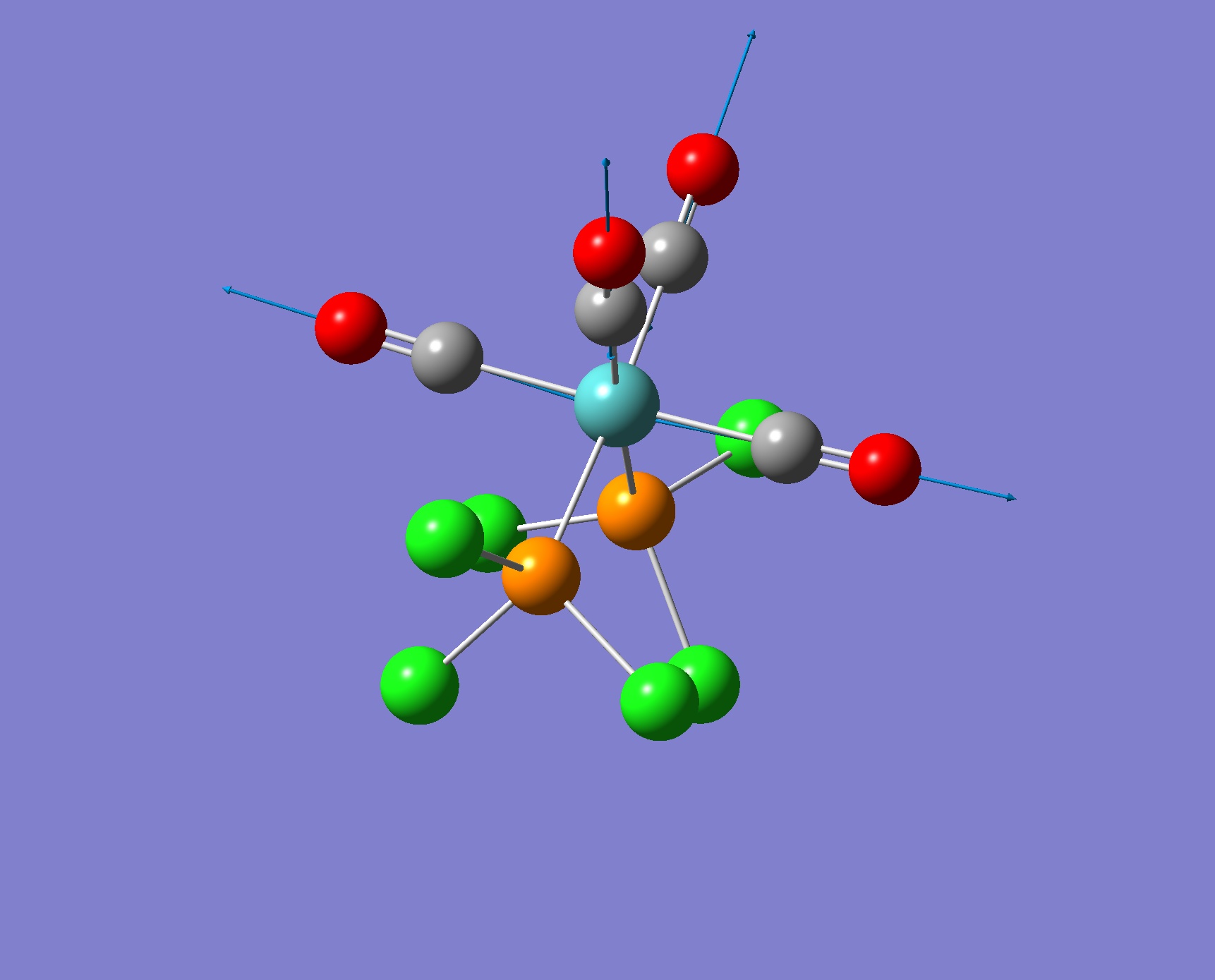

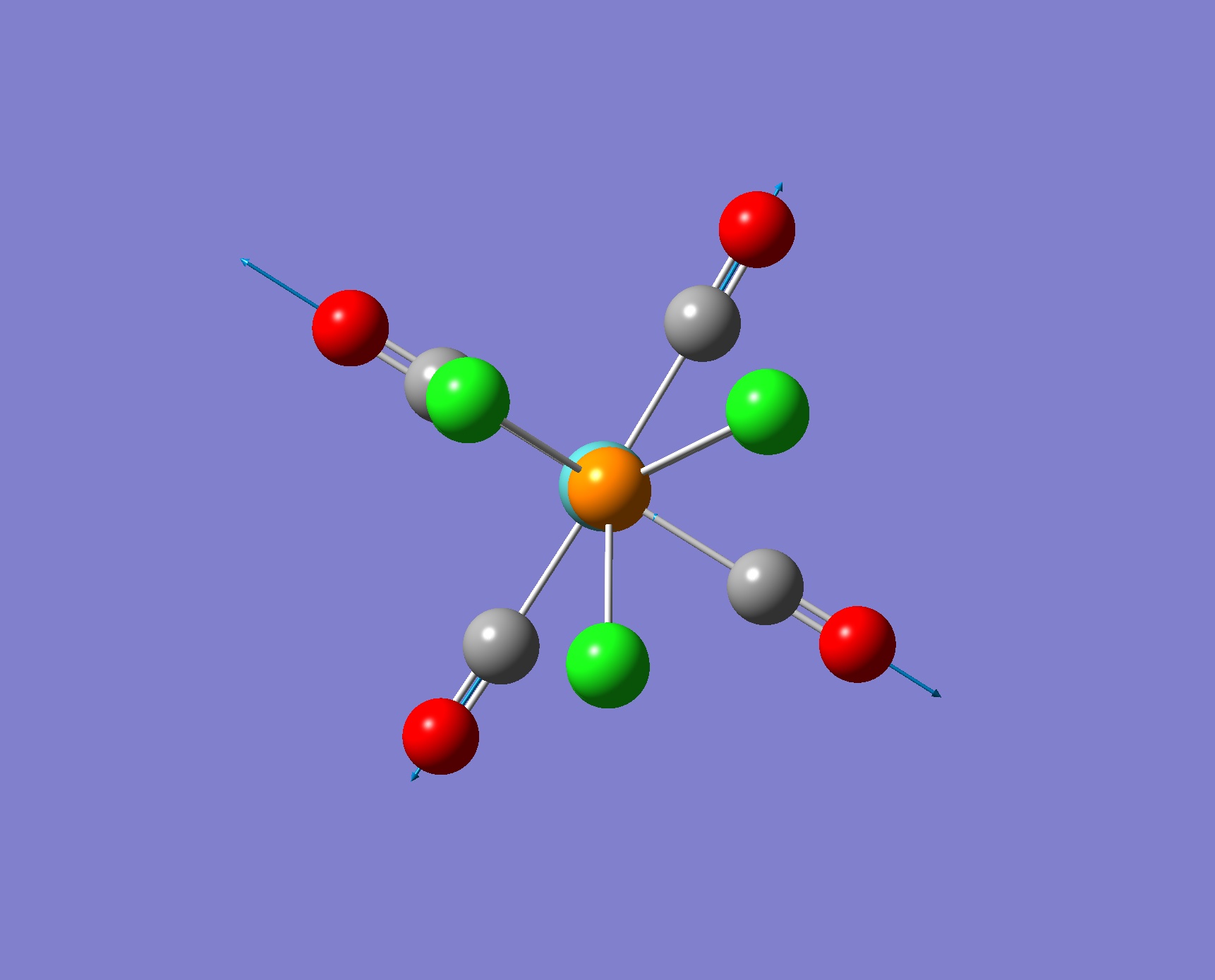

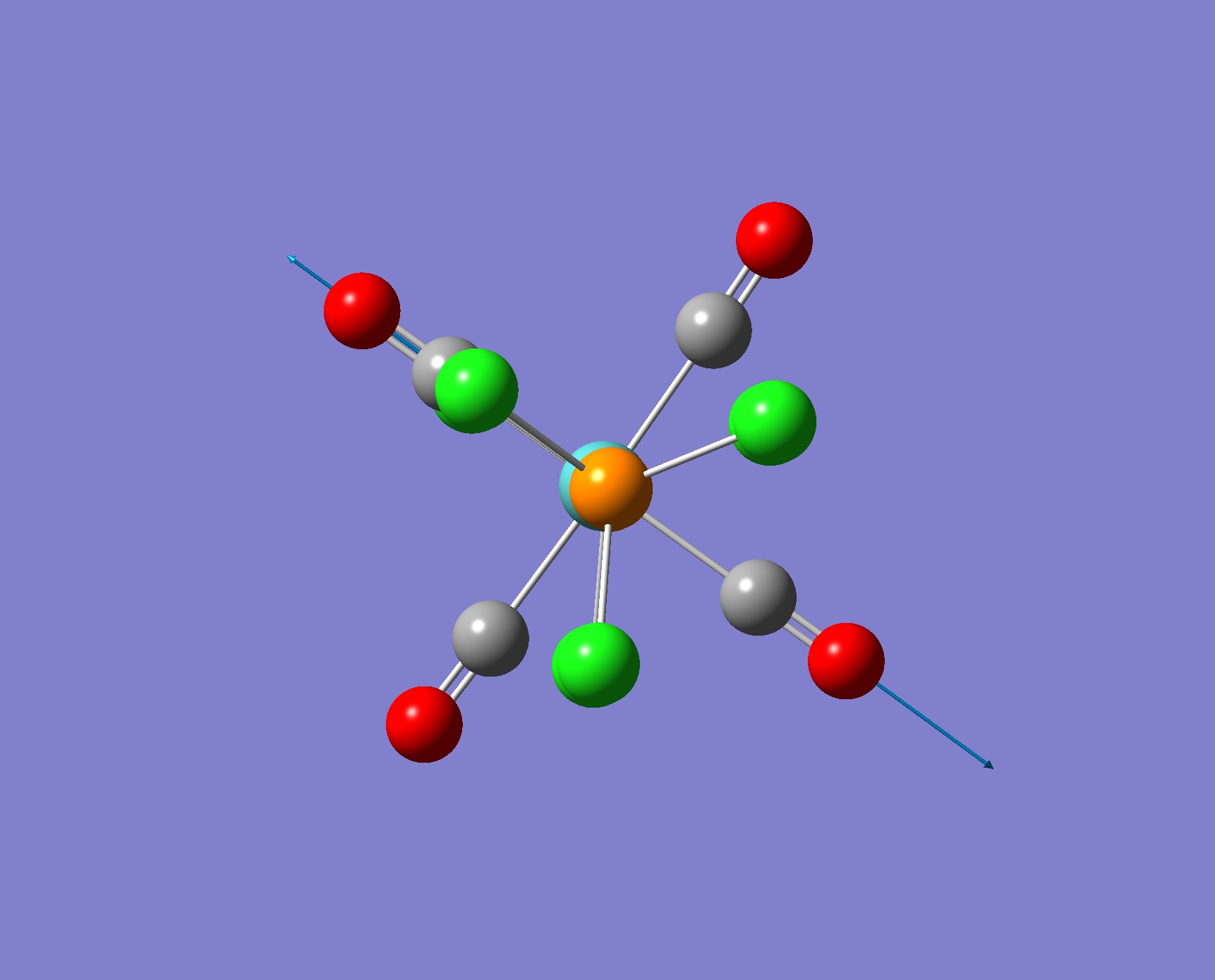

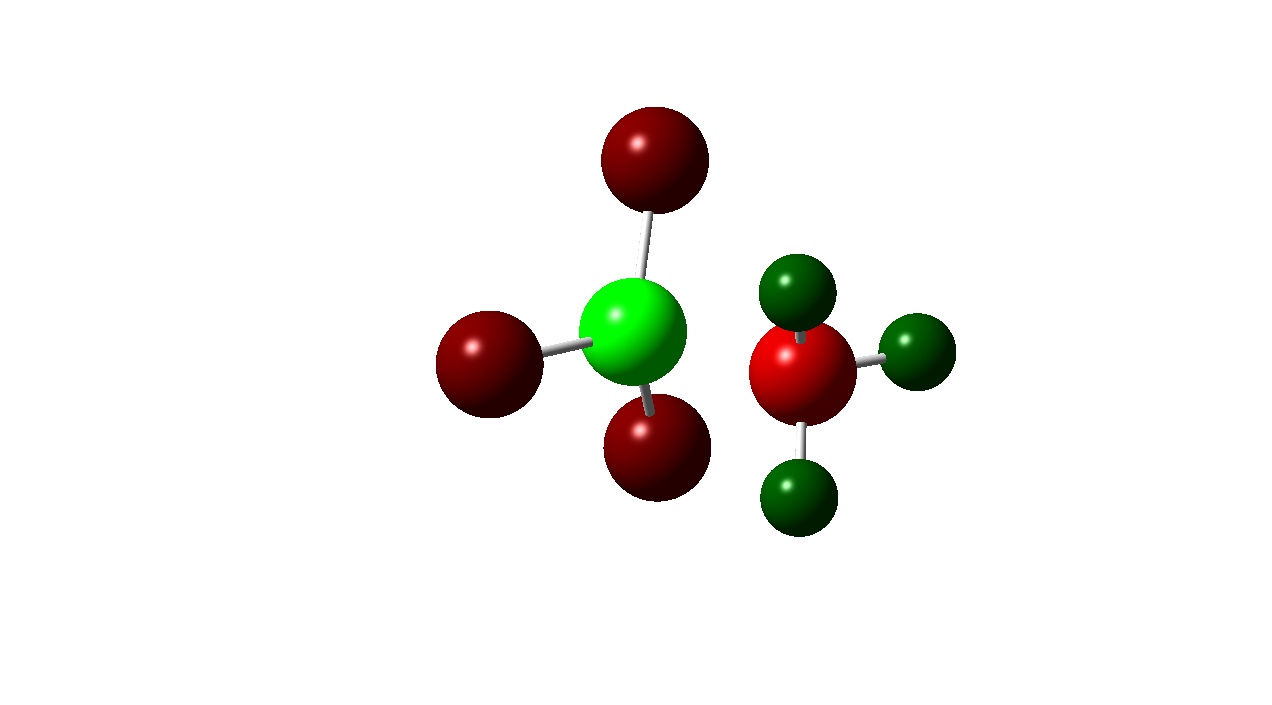

A Study of cis- and trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

In this section, the results from calculations performed to predict the relative thermal stability adn the spectral characteristics of the two isomers cis- and trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2.

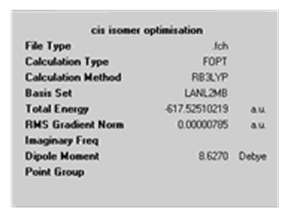

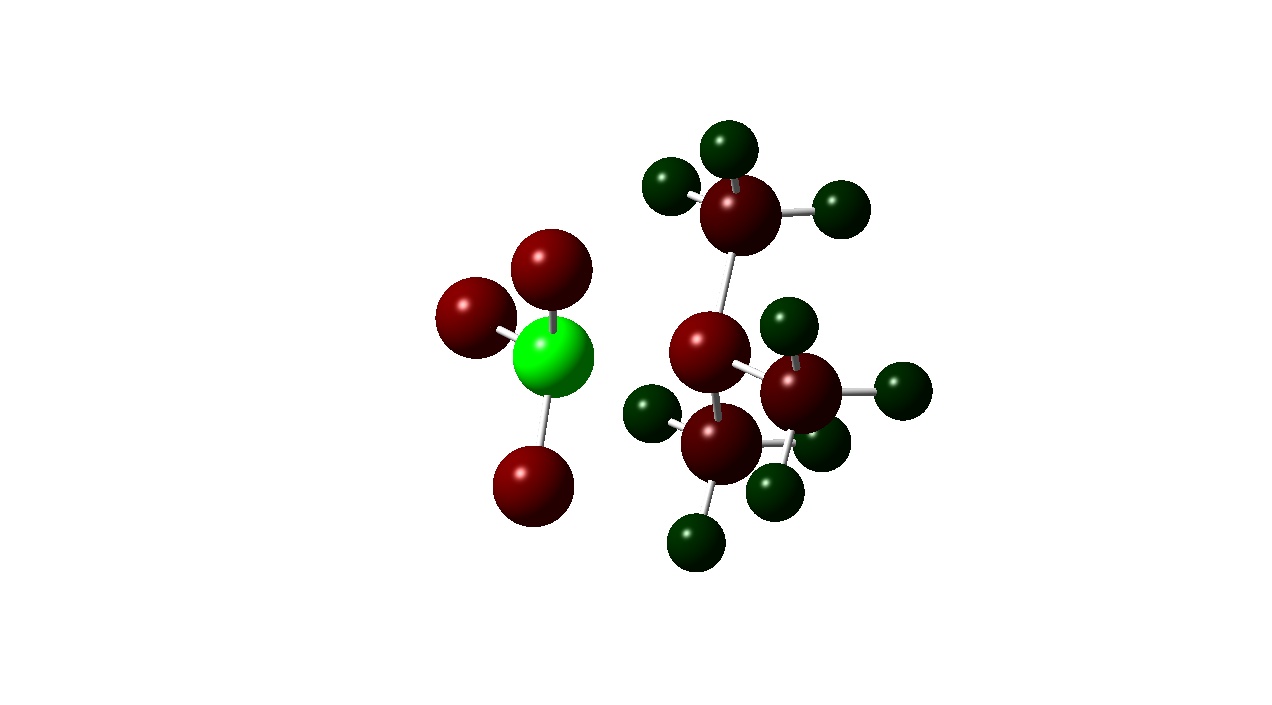

Optimisation of cis- and trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

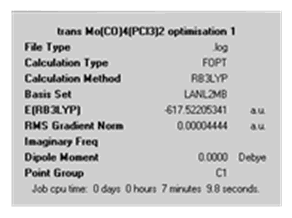

In order to get a good result the optimisation of the cis- and trans- isomers were carried out in three steps. These calculations were done via the SCAN service as they are more intensive. Both the cis- and trans- isomers were created in Gaussview 3.0. The first step involved an optimisation calculation using the B3LYP method, LAN2MB basis set and the additional keywords ‘opt=loose’ in order to get a rough starting geometry for the further optimisation later. From this calculation the results shown below were achieved.

| Heading for column 1 | Cis Isomer | Trans Isomer |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Summary |

|

|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

| jmol | ||

| D space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4491 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4492 |

Looking at the ‘real’ output file, it can be seen that a optimised structure was obtained. The P-Cl bonds are missing in the structure for reasons already discussed above.

The structures obtained from this first optimisation were manipulated as shown below before another optimisation calculation as the settings chosen does not describe dihedral angles well and can lead to achieving a structure from the wrong minima.

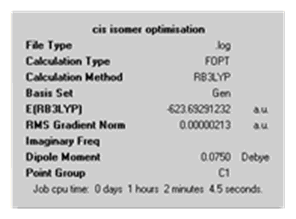

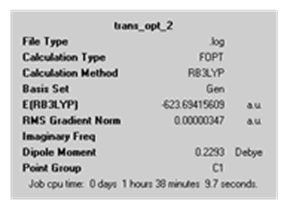

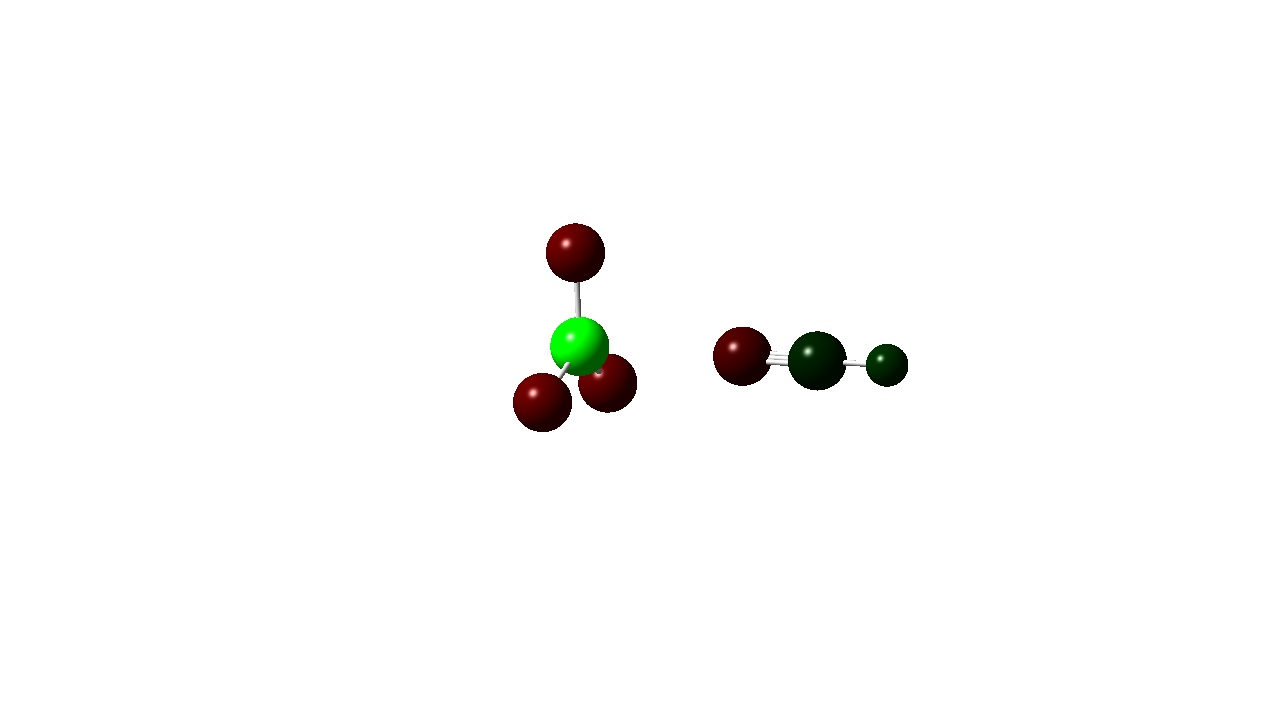

Using the structure from the first optimisation, a further optimisation calculation was then performed using the B3LYP method and the much better pseudo-potential and basis set LANL2DZ. The additional keywords ‘opt=loose’ were removed and replaced with ‘int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 in order to increase the electronic convergence. The results achieved from this calculation are shown below.

| Cis Isomer | Trans Isomer | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Summary |

|

|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

| jmol | ||

| D space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4493 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4494 |

Again, looking at the ‘real’ output file, it can be seen that a fully optimised structure was obtained. The P-Cl bonds are no longer missing in the structure meaning that the P-Cl bond length is now within the pre-defined parameters in the programs for the longest bond length.

Relative Energies of cis and trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

The calculation summary from the final optimisation of the cis and trans isomers shows their energies to be -623.693 and -623.694 a.u (or -1637505 and -1637508 kJ/mol) respectively. This shows that the trans isomer is slightly lower in energy and therefore the more stable isomer. This higher stability can be attributed to the molecule experiencing less steric strain as the PCl3 groups are farther apart.

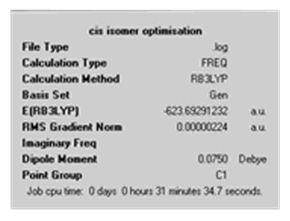

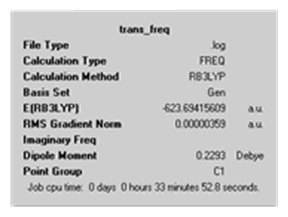

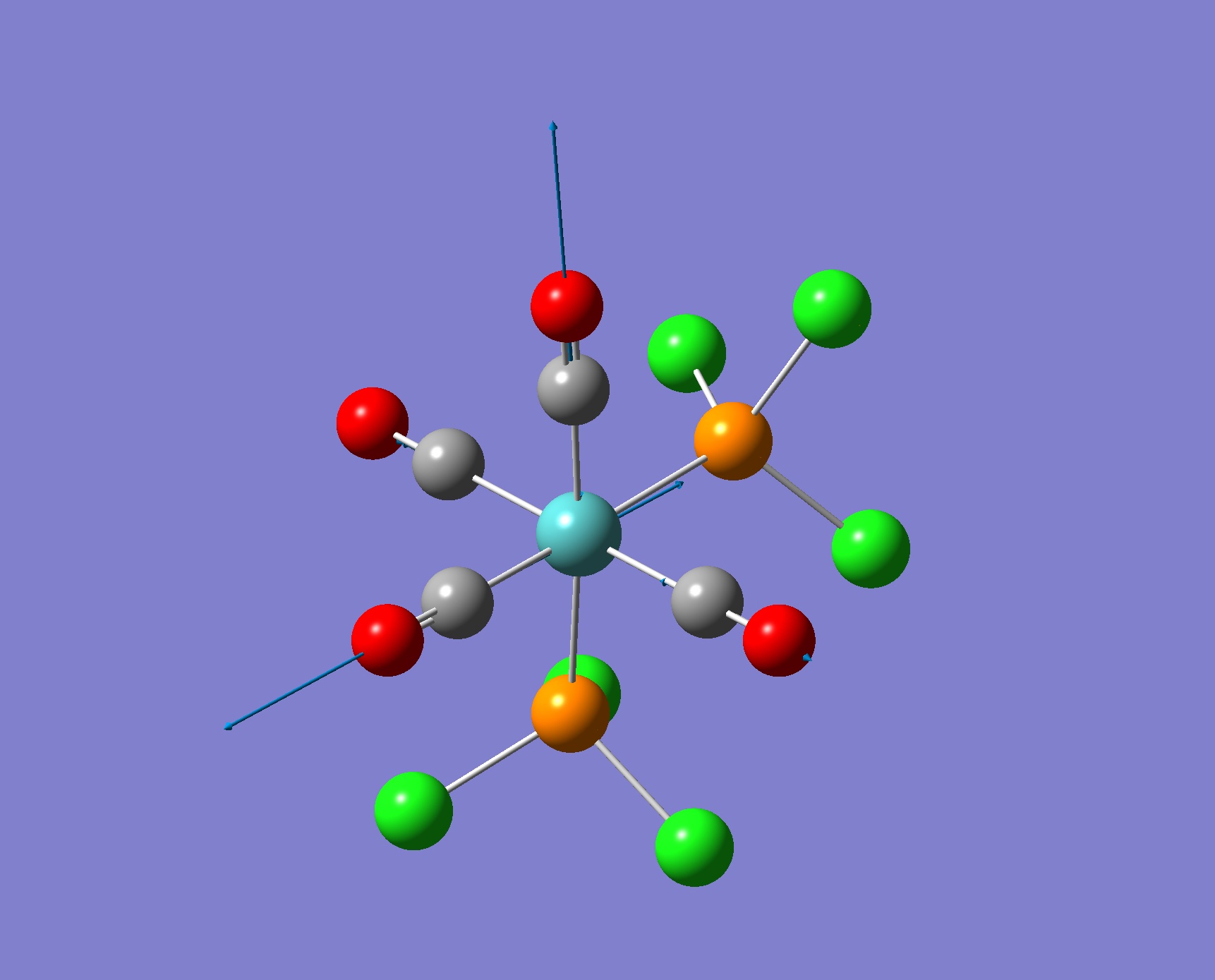

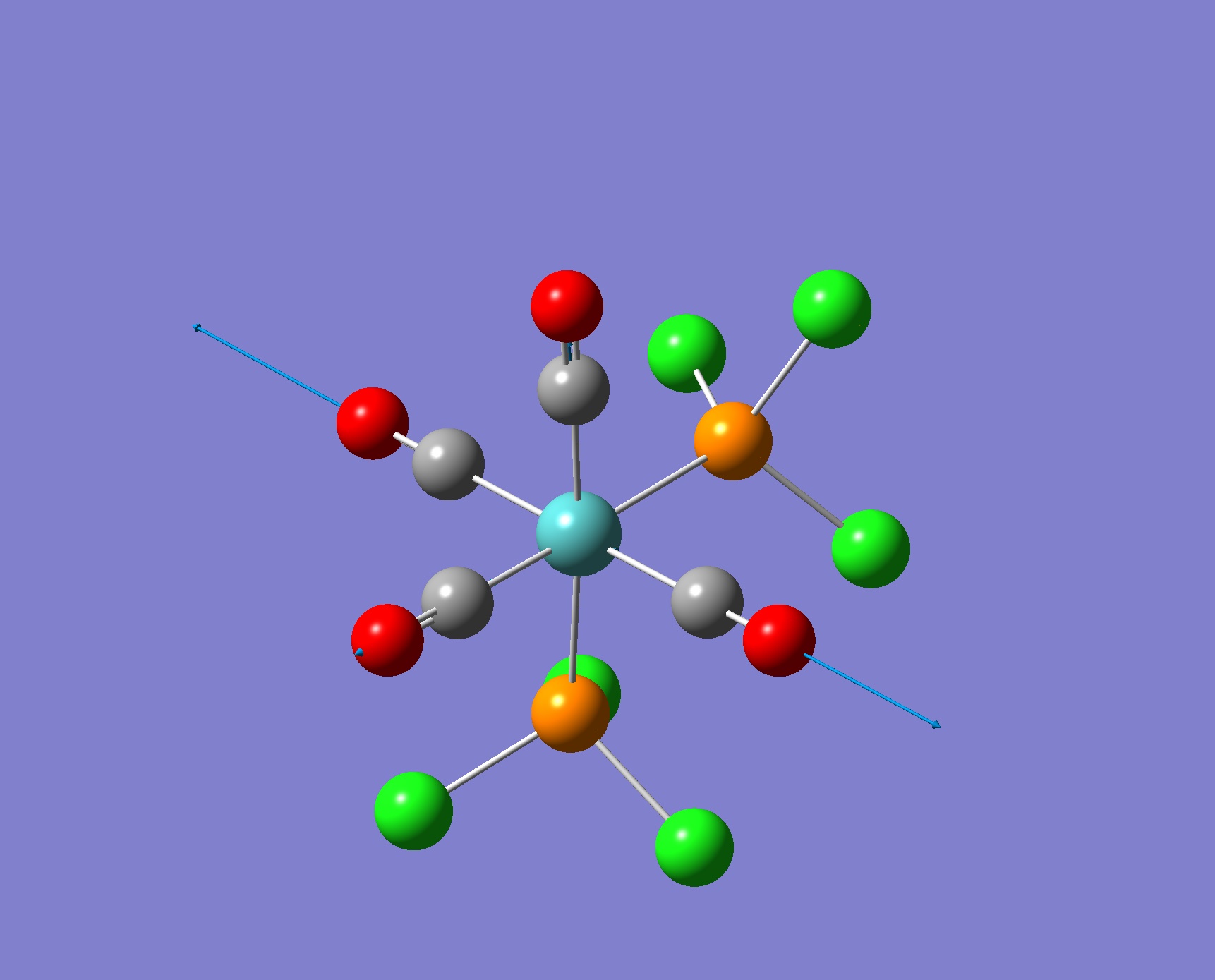

Frequency Analysis of cis- and trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

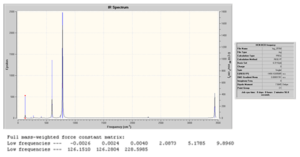

In order to confirm that an optimised geometry was obtained, we must now carry out a frequency analysis on the optimised geometries of the cis and trans isomers. Using the supposed optimised structure of the isomers, the IR frequencies were computed using the same method/ basis set and options are the optimisation. The results obtained are shown below.

D space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4495

D space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4496

From the above, we can confirm that an optimised geometry was achieved. For both the cis and trans isomers, the low frequencies are acceptable as they are close to zero and only slightly negative (which is due to numerical difficulties).

Let’s now consider the IR spectra of the isomers in greater detail. As there is a direct relationship between the geometry of a metal carbonyl complex and the number of CO stretching bands that are IR active, one can look at the IR spectra of these two isomers and distinguish between them. [8] Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 has D4h symmetry while the cis isomer has C2v symmetry. This means that one would expect to find one and four CO stretching bands for the trans and cis isomer respectively.

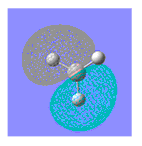

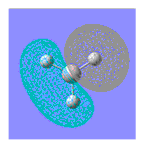

| Screenshot of Vibration for the cis Isomer | Frequency from Calculation/ cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency/ cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2019 | 541 | 2072 |

|

1953 | 592 | 2004 |

|

1942 | 821 | 2001 |

|

1939 | 1597 | 1986 |

| Screenshot of Vibration | Frequency from Calculation/ cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency/ cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2025 | 5 | n/a |

|

1966 | 6 | n/a |

|

1939 | 1606 | 1896 |

|

1939 | 1605 | 1896 |

As predicted from symmetry the cis and trans isomers have four and one CO stretching bands in their respective IR spectrum. Although there are 4 vibrations of the trans isomers only one peaks is observed in the spectrum as two stretches are of low intensity (corresponding to symmetric motions) and the other two vibrations absorb at the same frequency so only one peak is seen. There is relatively good agreement with the literature values. This illustrates the usefulness of such computational techniques as we are able to obtain the IR spectra of compounds without having to synthesise them first.

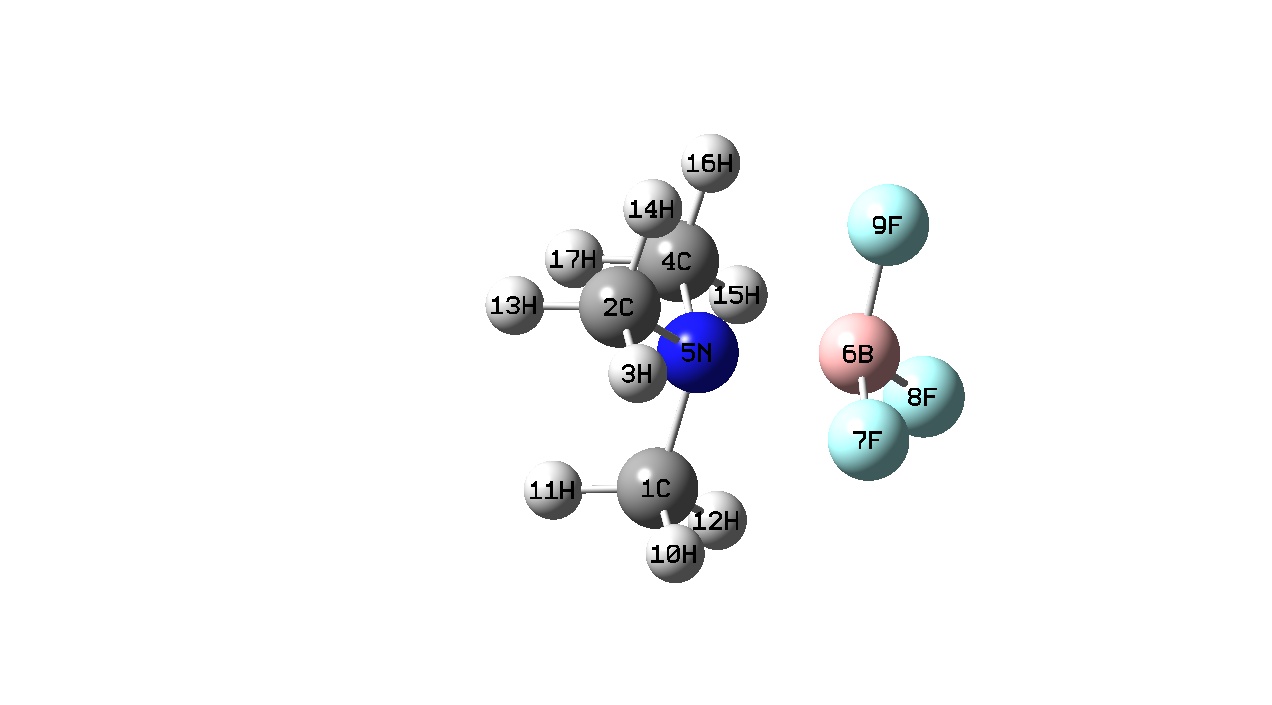

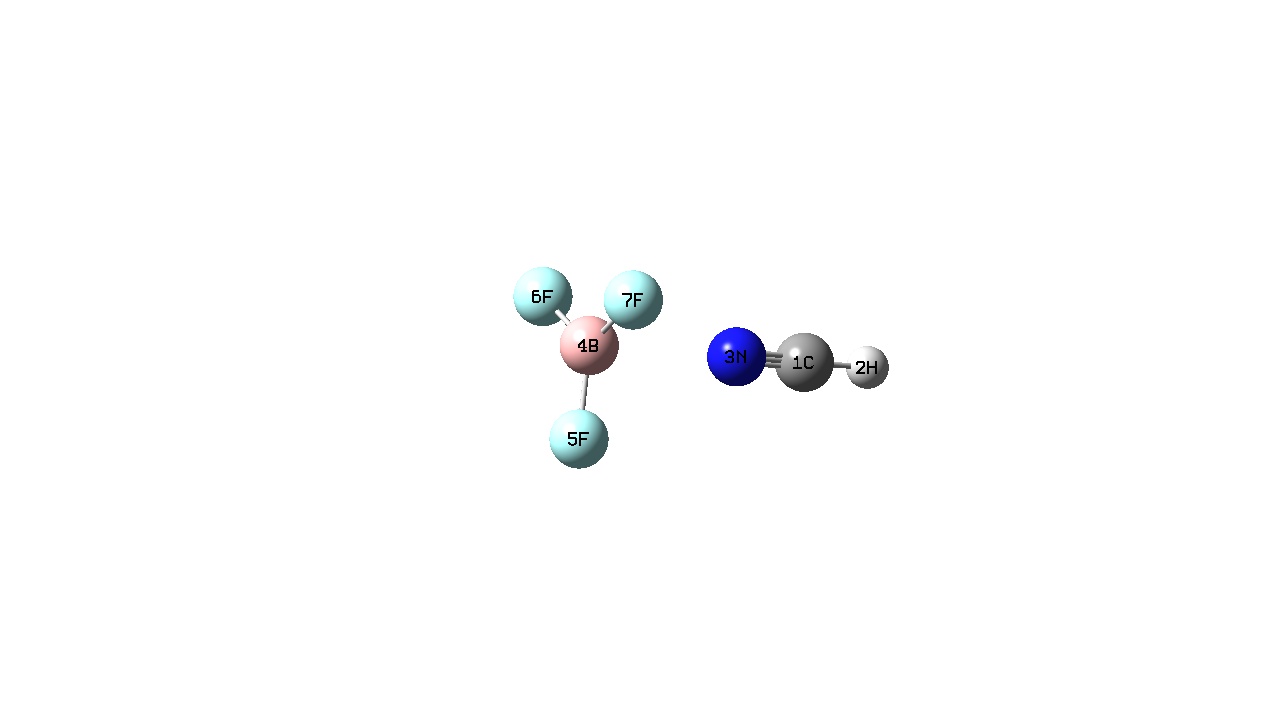

Mini-Project: A study of Lewis Acid-Base Complexes

This mini-project aims to investigate 6 Lewis acid-base complexes using computational methods learnt so far. These complexes include: H3N-BF3 (1), Me3N-BF3 (2), HCN-BF3 (3), MeCN-BF3 (4), H3N-BCl3 (5) and HCN-BCl3 (6). Calculations will be carried out in order to obtain the optimised geometries of these compounds focussing on the differences in the B-N and B-X bond distances upon complexation. In order to confirm that optimisation was successful, vibrational analysis will be carried out on the optimised structures. The B-F stretching frequency will then be compared between BF3 and Me3N-BF3 to see whether this agrees with the bond lengths found from the optimised geometry. NBO analysis will also be performed on the complexes. This will give us detail about atomic charges and charge transfer. We will see if a there is a trend between charge transfer and bond length (which is proportional to bond strength). Finally through molecular orbital analysis, the bond lengths found from optimisation will be considered with regards to the relative energies of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) of the base and the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) of the acid. From analysis of the MOs of the free BF3 and BCl3 the relative acidities of these acids will be discussed.

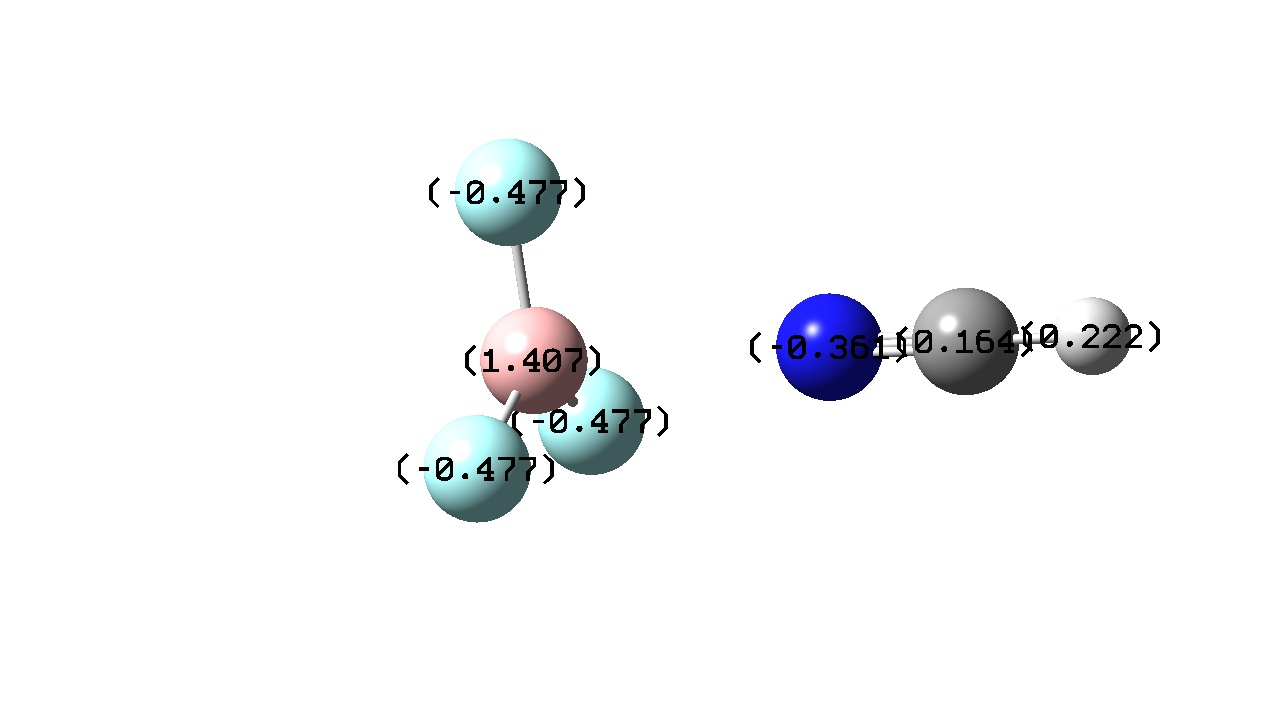

Optimising the Geometry of the Free Lewis Acids and Bases

In order to analyse the geometries of the Lewis acid-base complexes. one must consider the species when free first. Optimisation calculations were carried out using the B3LYP method and the basis set 6-311G(d). Calculations were sent to the scan service. This basis set was chosen as a good level for the calculations balancing the accuracy and length of the calculations.

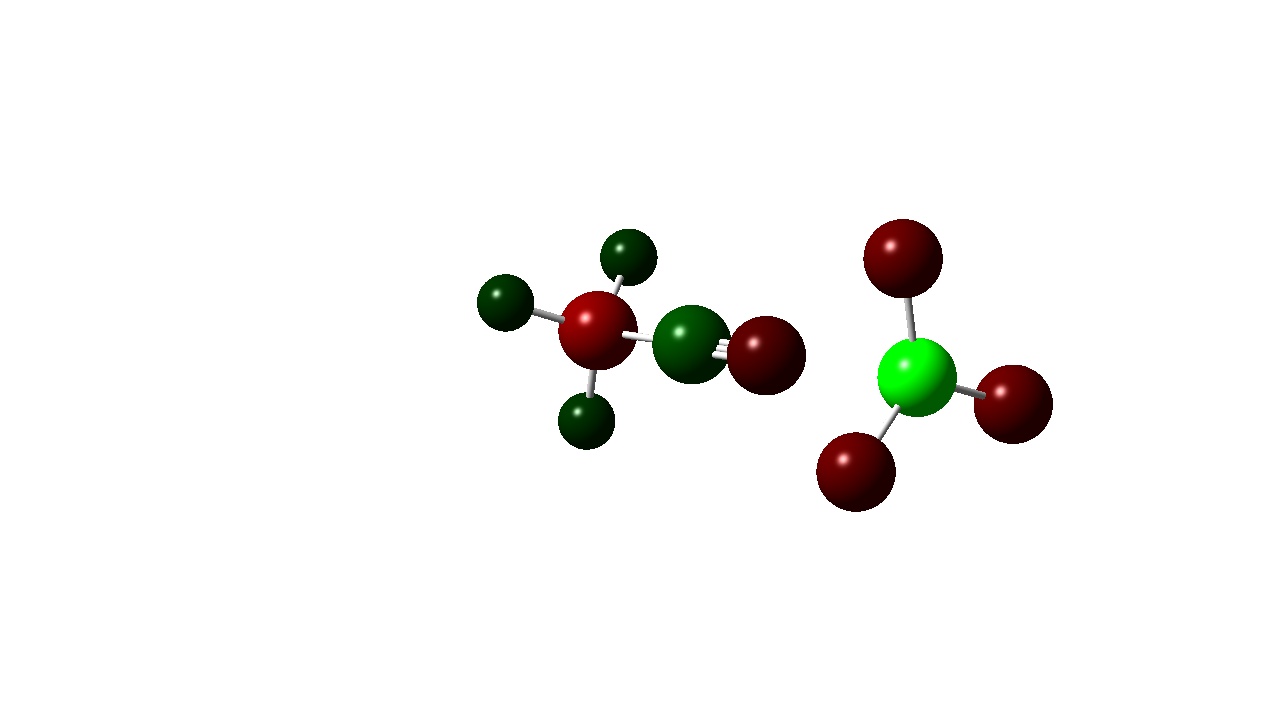

| BF3 | BCl3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

| jmol | ||

| B-X Bond Distance/ Å | 1.32 | 1.75 |

| X-B-X Bond Angle/ ⁰ | 120.0 | 120.0 |

| D-space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4576 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4575 |

Both acids are trigonal planar. The B-X bond distance is greater the BCl3 than BF3 as chlorine is a bigger atom.

| NH3 | NMe3 | HCN | MeCN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

|

|

| jmol | ||||

| D-space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4577 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4578 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4579 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4580 |

Optimising the Geometry of the Complexes

Optimisation calculations were carried out using the B3LYP method and the basis set 6-311G(d) again (thereby ensuring all results are comparable. As the adducts being investigated are quite small there is no need to use pseudo-potentials for the structures.

| H3N-BF3 (1) | Me3N-BF3 (2) | HCN-BF3 (3) | MeCN-BF3 (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

|

|

| jmol | ||||

| Calculated B-N Bond Distance/ Å | 1.70 | 1.69 | 2.49 | 2.33 |

| Experimental B-N Bond Distance (Gas Phase)/ Å | 1.657 ±0.02[9] | 1.656 ±0.002[10] | 2.473 ±0.029[11] | 2.011 ±0.007[12] |

| Difference between Calculated and Experimental B-N Bond Distance/ Å | 0.043 ±0.02 | 0.034 ±0.002 | 0.017 ±0.029 | 0.319 ±0.007 |

| Calculated B-F Bond Distance/ Å | 1.37 | 1.38 | 1.32 | 1.33 |

| Experimental B-F Bond Distance (Gas Phase) [13] / Å | 1.367 | 1.374 | 1.317 | 1.323 |

| Difference between Calculated and Experimental B-F Bond Distance/ Å | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.007 |

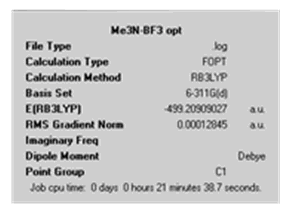

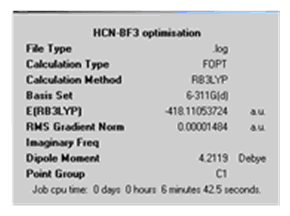

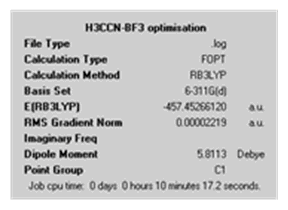

| Calculation Summary |

|

|

|

|

| D space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4518 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4519 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4520 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4521 |

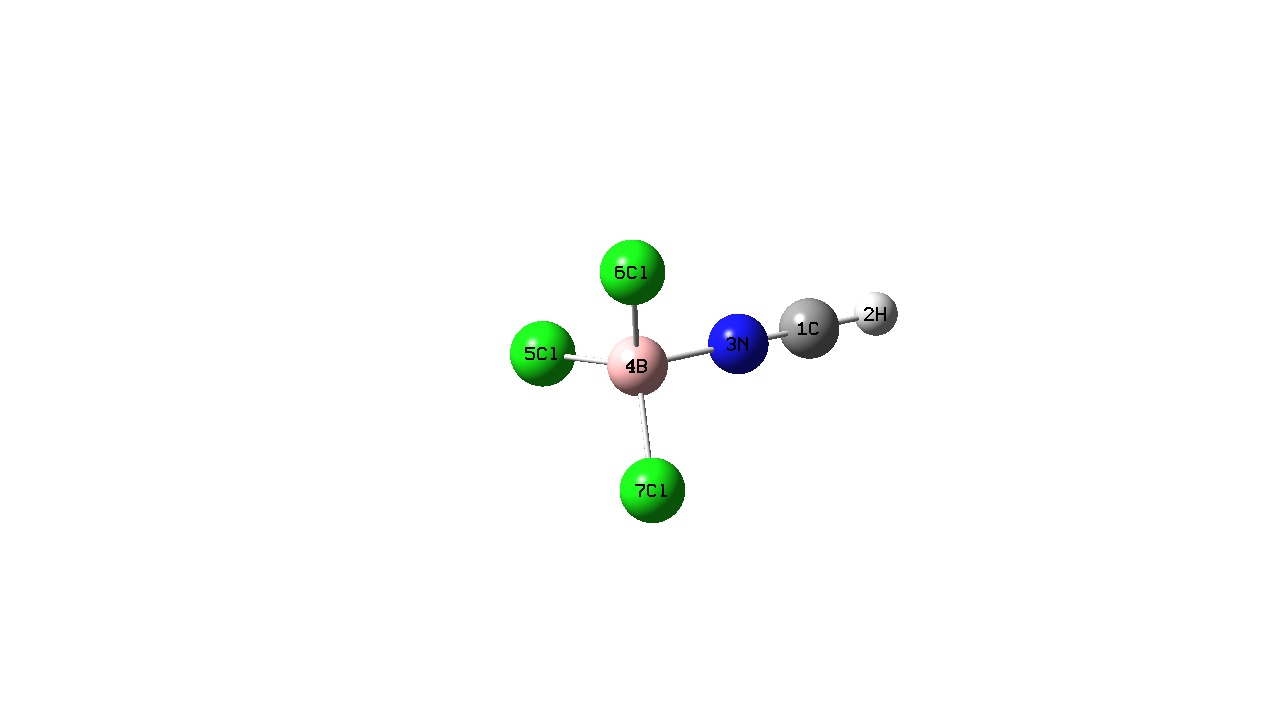

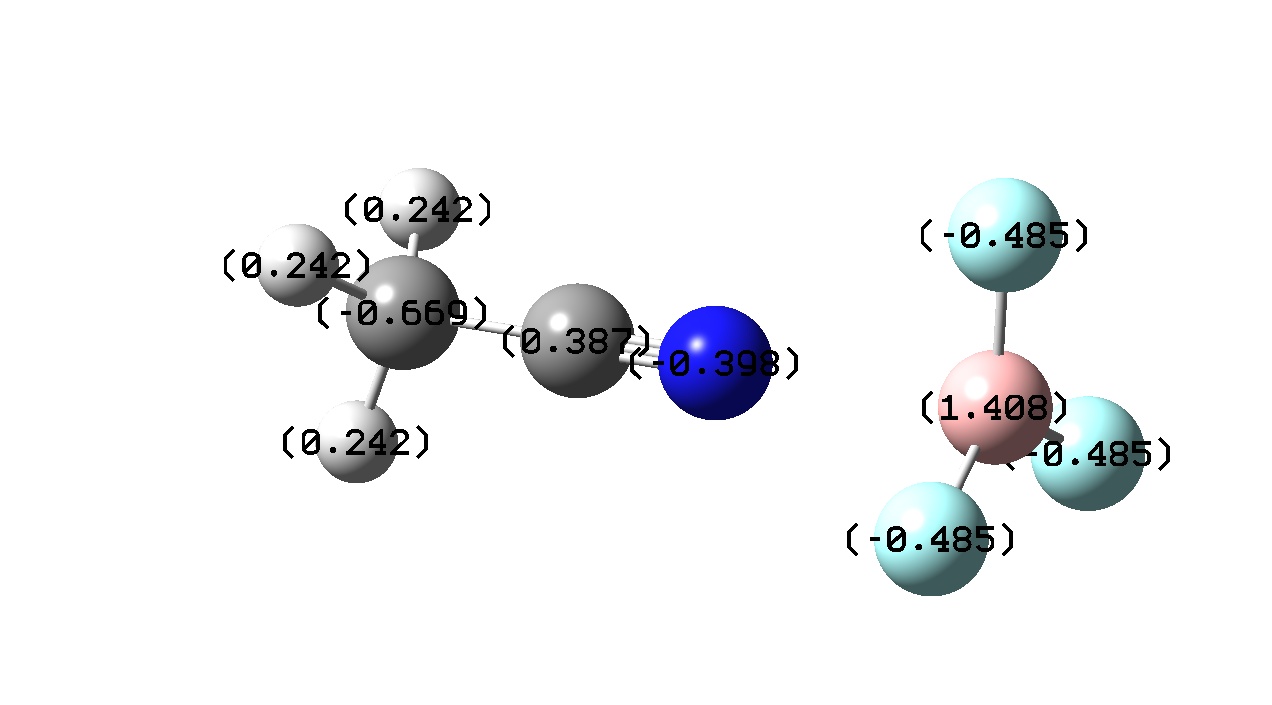

| H3N-BCl3 (5) | HCN-BCl3 (6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Optimised Structure |

|

|

| jmol | ||

| Calculated B-N Bond Distance/ Å | 1.63 | 1.62 |

| Experimental B-N Bond Distance / Å | 1.630 [13] | n/a |

| Difference between Calculated and Experimental B-N Bond Distance/ Å | 0.00 | n/a |

| Calculated B-Cl Bond Distance/ Å | 1.84 | 1.83 |

| Experimental B-Cl Bond Distance [13] /Å | 1.813 | n/a |

| Difference between Calculated and Experimental B-Cl Bond Distance/ Å | 0.027 | n/a |

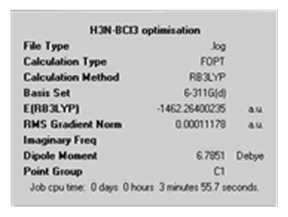

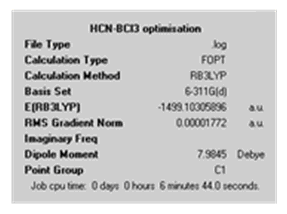

| Calculation Summary |

|

|

| D space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4522 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4523 |

All the BF3 complexes (i.e. complexes 1-4) do not show a visible B-N bond. As discussed previously, this does not mean that a bond does not exist rather that the bond length is greater than the longest length pre-defined in the program. It has been suggested that adducts 3 and 4 should be considered as Van der Waal’s complexes. [13] Complexes 3 and 4 show a planar geometry around the Boron atom while complexes 1 and 2 have a tetrahedral arrangement around the Boron atom with an N-B-F bond angle of 104 and 105 Å respectively. The B-F bonds are longer when in a complex compared to when they are free. This can be explained as when free the Boron orbital is sp2 hydridised which changes on complexation to sp3. We can see as a stronger Lewis base is used to form the adduct, the B-N bond length decreases and the B-F bond becomes longer. In other words as a stronger Lewis base is used the B-N bond becomes stronger and the B-F bond becomes weaker. This is because the Me3N contains three electron donating methyl groups and therefore has a greater Lewis basicity compared to the other being investigated. This means that the nitrogen atom of Me3N has a greater electron density compared to the other Lewis bases and can therefore donate more electron density to the electron deficient Boron atom resulting in a stronger bond. From this we can also deduce that Me3N is the strongest of the Lewis bases being investigated here.

From the above, we can also see that BCl3 is a stronger acid than BF3. Comparing complexes 1 and 5, the same Lewis base is used but on changing the acid from BF3 to BCl3 the B-N bond has become 0.07 Å shorter (This is also the case when comparing complexes 3 and 6). This means that the bond is stronger and therefore the Boron atom of the BCl3 complex is more electron deficient than that of the BF3 complex. Considering that Fluorine is more electronegative than Chlorine this is counter-intuitive. Just looking at the bond lengths the greater acidity of BCl3 can be explained by stronger covalent attrations in the BCl3 complex compared to the BF3. In 2003, this was also suggested by F. Bessac and G. Frenkling. [14] This finding will be discussed further during the molecular orbital analysis. The calculated and experimental bond lengths agree well. For most of the complexes the calculated bond distance is slightly greater than that cited in the literature. In order to see if even better agreement could be achieved, one could used a larger basis set.

Vibrational Analysis of the Complexes

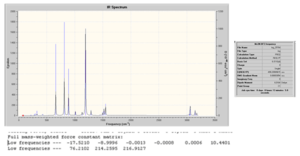

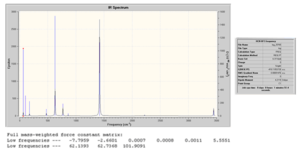

It can be seen from above that all the optimisations converged. This tells us that the geometry have been optimised. This will now be confirmed through vibrational analysis.

D-space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4596

D-space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4597

D-space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4598

D-space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4599

D-space file:http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4600

D-space file:http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4601

From the above, we can see that no negative frequencies were obtained and so the optimisation was successful. It would now be interesting to see the effect of complexation on the B-F stretch. We have seen already when analysing the bond lengths of the optimised geometries that on complexation the B-F bond of the BF3 adducts becomes longer (or weaker) compared to free BF3. We would therefore predict that as a stronger base is used and the B-F bond becomes longer therefore leading to a decrease in the B-F stretching frequency. This will now be examined.

D-space file: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4613

| Vibrational B-H Mode | Calulated BF3/ cm-1 | Calculated F3B-NMe3/ cm-1 (2) | Lit. BF3 [15] / cm-1 | Lit. F3B-NMe3 [16] / cm-1 | Difference between Calculated and Lit. BF3/ cm-1 | Difference between Calculated and Lit F3B-NMe3/ cm-1(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deformation | 474 | 428 | 482 | 340 | 8 | 88 |

| Deformation | 685 | 658 | 718 | 550 | 33 | 108 |

| Symmetric Stretch | 875 | 887 | 888 | 952 | 13 | 65 |

| Asymmetric Stretch | 1442 | 1190 | 1505 | 1165 | 63 | 25 |

The calculated stretching frequencies agree with the values cited in the literature. Discrepancies in frequency can again be attributed to the level of calculation. From the above table we can see that for three out of the four B-F vibrational modes the stretching frequency of the B-F bond decreases upon complexation. However, unexpectedly the symmetric stretch frequency increases upon complexation. It has been suggested that this is due to the mixing of the B-F symmetric stretch with the B-N stretching mode which results in in-phase and out-of-phase NBF3 symmetric stretches. [16] [17] Given more time, one might repeat this exercise with the stronger Lewis acid BCl3 to see if the same trend is observed.

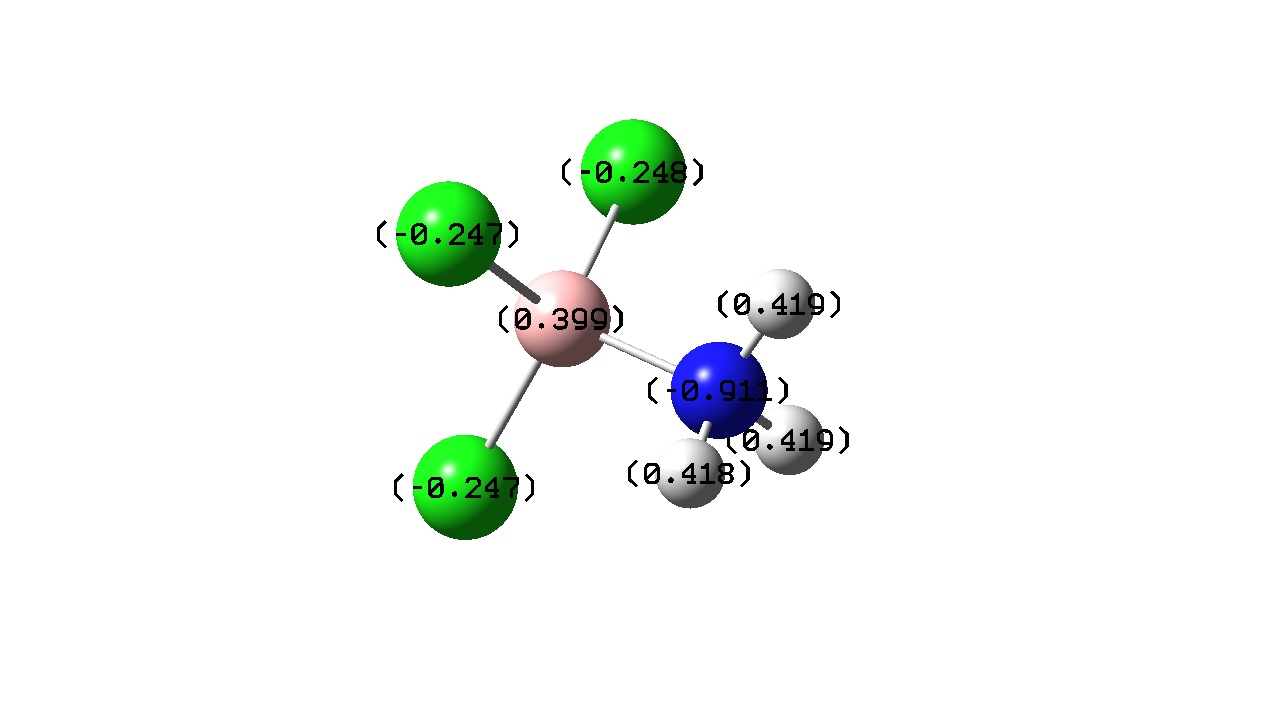

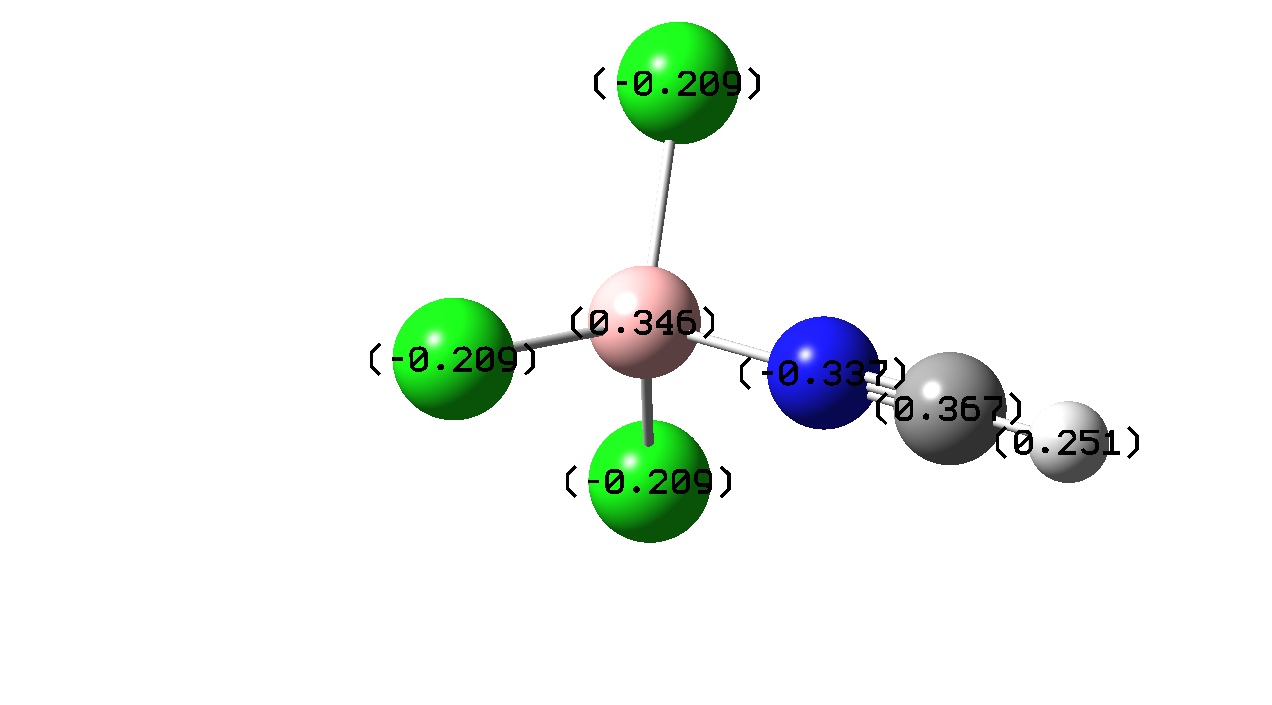

NBO Analysis of the Complexes

| H3N-BF3 (1) | Me3N-BF3 (2) | HCN-BF3 (3) | MeCN-BF3 (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour Charge |

|

|

|

|

| Atomic Charge/ C |

|

|

|

|

| Charge Transfer | - 0.293 | - 0.281 | - 0.024 | -0.047 |

| D-space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4530 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4531 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4532 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4533 |

| H3N-BCl3 (5) | HCN-BCl3 (6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Colour Charge |

|

|

| Atomic Charge/ C |

|

|

| Charge Transfer | -0.432 | -0.281 |

| D-space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4534 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4535 |

If one considers bond length to be proportional to bond strength then one might expect that greater charge transfer would lead to a stronger bond. However, from the above it seems that there is no exact trend between bond length and charge transfer. This was also found by J. Volker et al. and may be due to the calculation level used in both cases. [13] F. Bessac and G. Frenkling also found using atomic charges to estimate bond strength unreliable. [14] Although a precise trend cannot be found here, a pattern is noticed when comparing charge transfer with a change in Lewis acidity and basicity.

Looking at the BF3 complexes, we can see that the stronger Lewis bases (i.e NH3 and NMe3) show much greater charge transfer than the weaker bases (i.e. HCN and MeCN) and as expected have a shorter (or stronger) bonds. This is expected as a stronger Lewis base would donate greater electron density to the electron deficient Boron atom. The complexes formed with the weaker bases show virtually no charge transfer.

Another pattern observed is that the Boron atom is more positive for the BF3 complexes than the BCl3 ones. This is due to the electronegativities of the halogens present in the adduct. Fluorine in more electronegative than chlorine and the electron densitiy donated by the Nitrogen atom to the boron is ‘pulled’ towards the Fluorine atom wheares with the BCl3 adducts the donated electron density is ‘pulled’ towards less by the less electronegative chlorine . This is also evident from the atomic charges on the halogens. Fluorine has a more negative atomic charge as it is has more electron density located around it.

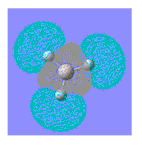

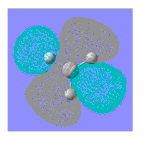

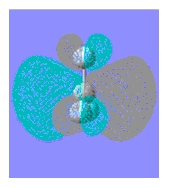

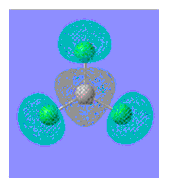

Molecular Orbital Analysis of the Free and Complexed Lewis Acids and Bases

One cannot analyse acid-base complexes without studying the molecular orbitals of the free acids and bases. An interaction is formed as electron density is donated from the Highest Occupied Moleular Orbital (HOMO)of the base to the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) of the acid. The strength of this interaction is dependent on the these MOs being of the correct symmetry, well matched in energy and hardness. In examining these complexes we also cannot ignore Pearson’s HSAB (Hard Soft Acid Base) Theory which states hard-hard and soft-soft acids and bases will have a stronger interaction than hard-soft combinations. Here we will look at the both the LUMOs and HOMOs of the acids and bases to consider which pair we would expect to have the strongest interaction and see whether this corresponds to the strongest (shortest) bond.

| BF3 | BCl3 | NH3 | NMe3 | HCN | MeCN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LUMO Energy | 0.018 | - 0.076 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.011 | 0.026 |

| HOMO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| HOMO Energy | - 0.428 | - 0.329 | - 0.256 | - 0.202 | - 0.360 | - 0.336 |

| Hardness | 0.223 | 0.124 | 0.141 | 0.120 | 0.179 | 0.181 |

| D-space file | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4614 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4615 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4616 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4617 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4618 | http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-4619 |

From Pearson’s theory, it is known that hard acids prefer to form stronger interactions with hard bases and likewise that soft acids like to form stronger interactions with soft bases. Hardness can be defined as:

Softness is the reciprocal of hardness. Therefore we expect the acid and base with the most similar value of hardness to have the strongest bond. This is the case when looking at the BF3 complexes. From the table above. We can see that free BF3 and Me3N have the most similar hardness value and their respective LUMO and HOMOs are the most similar in energy of the acid base pairs being investigated. We would therefore expect their interaction to be the strongest and this was found to be the case earlier during the optimised geometry analysis. However, this approach does not hold for the two BCl3 complexes being studied here. One would expect a stronger interaction (and therefore a shorter bond) between NH3 and BCl3 as they are of similar softness and the energies of their respective HOMO and LUMOs are more similar than the acid-base pair HCN and BCl3. However, this can be explained by considering steric factors. HCN is less bulky than NH3 and so on complexation the B-Cl bond does not have to lengthen as much in order to reduce repulsion and a steric clash.

From the above we can also see that BF3 is a harder acid that BCl3 from the calculations of hardness. This means that the former will prefer to interact with bases of a similar hardess and indicates that its more likely to form ionic interaction while BCl3 as a soft acid is more likely to form an covalent interaction with the base.The HOMO of the harder bases are dense and contracted as the LUMO of the harder acid BCl3 Whereas the HOMOs of the softer bases and acid are diffuse and polarisable.[19]

Looking at the relative LUMO energies of the free acids we can find another explanation as to why BCl3 is a stronger acid than BF3. Frontier Orbital Model of Chemical Reactivity suggests the as The LUMO of BCl3 lies lower in energy than that of BF3 it will have stronger covalent interactions with HOMO of the base. This agrees with bond lengths (strengths) found of the optimised geometries of the BF3 and BCl3 complexes as the later had shorter (or stronger) donor-acceptor bonds.[20]

Conclusion

This mini-project has shown the usefulness of computational methods in investigating various aspects of a group of Lewis acid-base complexes without having to step into a laboratory. It has been confirmed that BCl3 is a stronger acid than BF3 from analysis of the optimised geometries of the complexes and molecular orbital analysis of the free acids and bases. It was proven through vibrational analysis that optimisations of the complexes were successful. From the NBO analysis, it was seen that charge transfer is greater for stronger bases. Where comparisons have been made possiblewith literature and it has been seen that the computed results agree well. Given more time, it would be useful and further improve this report if Me3N-BCl3 and MeN-BCl3 were also examined so that a full comparison of trends between the BF3 and BCl3 complexes could be made. To further examine this group of complexes and based on the results found here one might perform a series of displacement reactions and see whether the outcome agree with what has been found.

Conclusion

This report illustrates the usefulness of computational techniques to chemists. The resulting optimised geometries agree well with the literature and the chosen settings for calculations have proven to have the correct balance between accuracy and time taken. All optimised geometries were proved to be successful from vibrational analysis. It was shown the IR spectra of the cis- and trans- isomers Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 can be distinguished between each other by considering the number of CO stretches that will be IR active. Molecular orbital analysis of BH3 showed that although qualitative MO theory is good for generating MO diagrams, computational techniques are more accurate. NBO analysis also proved to be useful in determining the hybridisation of orbitals.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/2a_optimising_bh3.html

- ↑ Konecny, R. and Doren, D. J., J. Phys. Chem. B, 1997, 101 (51), 10984: DOI:10.1021/jp9726246

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 [http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/3b_understand_opt.html

- ↑ [http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_MOs_year2/L3_Tut_MO_diagram_BH3.pdf

- ↑ Greenwood, N. N., Earnshaw, A., Chemistry of the Elements, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2nd Edn., 1997

- ↑ Jain, M., Competition Science Vision Magazine, Pratiyogita Darpan Group, 2006, 8, 1453.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 [http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/10b_MoC4L2_opt.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Li. W, Zhou, G. and Mak, T. , Advanced Structural Inorganic Chemistry, OUP Oxford, 1st Edn., 2008, pp. 249 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Adv_structure" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Thorne, L. R.; Suenram, R. D.; Lovas, F., J. Chem. Phys., 1983, 78, 167DOI:10.1021/ic00296a031 10.1021/ic00296a031

- ↑ Iijima, K.; Adachi, N.; Shibata, S., Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 1984, 57, 3269 DOI:10.1246/bcsj.56.1891 10.1246/bcsj.56.1891

- ↑ Burns, W. A,; Leopold, K. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1993, 115, 11622DOI:10.1021/ja00077a081 10.1021/ja00077a081

- ↑ Dvorak, M. A.; Ford, R. S.; Suenram, R. D.; Lovas, F. J.; Leopold, K. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1992, 114, 108.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Volker, J.; Frenking, G.; Reetz M. T., J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1994, 8741, DOI:10.1021/ja00098a037

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bessac, F.; Frenking, G.; Reetz M. T., Inorg. Chem., 2003, 42, 7990, DOI:10.1002/chin.200404004

- ↑ Vanfereyn, J., J. Chem. Phys., 1959, 30, 331.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Amster, R. A.; Taylor, R. C., Spectrochim. Acta., 1964, 20, 1487.

- ↑ Montgomery, C. D., J. Chem. Educ., 2001, 78 (6), 840.

- ↑ Anderson, W.P., J. Chem. Educ., 2000, 77 (2), 209. DOI:10.1021/ed077p209 10.1021/ed077p209

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 www.joe-harrity.staff.shef.ac.uk/meetings/Hard_Soft.ppt

- ↑ Bessac, F.; Frenking, G.; Reetz M. T., Inorg. Chem., 2003, 42, 7990, DOI:10.1002/chin.200404004

Da907 14:16, 16 March 2010 (UTC)