Rep:Mod:CSWmodule2

Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital)

Introduction

BH3 Analysis

Borane is a simple molecule for which it is possible to undertake preliminary analysis using GaussView 5.0.9.

A molecule of BH3 was drawn in GaussView 5.0.9 and the B-H bonds lengths were set to 1.5Â.

BH3 Optimisation

An optimisation calculation is performed on BH3 using GaussView 5.0.9.

In this calculation we are making the assumption that the B and H nuclei are in fixed positions. The first calculation involves solving the Schrodinger equation for the electronic density and the energy. For the nuclei in the static, defined position, the energy (E) and densisty (rho) are obtained. This is called the SCF part of the calculation.

Then, the second part of the calculation involves moving the nuclei by a fixed amount to a new position and repeating the process above. If the new position is of lower energy than the first it is kept and the SCF process repeated. This repeats until an energy minima is found and is called the OPT part of the calculation.

The Gaussian Calculation was set up to run in the following way:

Method: B3LYP - (Type of approximations made when solving the Schrodinger equation) Basis set: 3-21G - (Accuracy) Type of Calculation: OPT

Once the calculation was completed, the .log file was opened in GaussView and the summary file viewed. The summary information is shown below:

BH3Optimisation File Name = BH3Optimisation File Type = .log Calculation Type = FOPT Calculation Method = RB3LYP Basis Set = 3-21G Charge = 0 Spin = Singlet E(RB3LYP) = -26.46226338 a.u. RMS Gradient Norm = 0.00020672 a.u. Imaginary Freq = Dipole Moment = 0.0000 Debye Point Group = D3H Job cpu time: 0 days 0 hours 0 minutes 21.0 seconds

- The calculation type is FOPT which means that Gaussian is requesting the full optimisation takes place. [1]

- The calculation method 'RB3LYP' describes the model that is used. Gaussian can be programmed to use slightly different mathematical models depending on the type of molecule under analysis and the information that is being obtained. RB3LYP is a standard model that is frequently used.

- The basis set 3-21G refers to the set of functions that are used to describe the molecular orbitals of the molecule. Basis sets can be of varying accuracy depending on the demands of the calculation.

- We can see that the final energy is -26.46 au (or -0.01 KJ/mol).

- From the information above it is possible to determine that the optimisation has been successful by noting that the gradient is very close to 0. This means that a minima on the potential energy curve has been found.

- The dipole moment is 0 Debye which simply shows that there is no dipole moment in the molecule.

- The point group has been determined as Dh3 and the calculation ran for 21s.

It is also possible to read the full text file by opening the .log file as a text document. This enables us to check that the calculation has converged, as seen in the information provided below:

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000413 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000271 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001610 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.001054 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.071764D-06

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

----------------------------

! Optimized Parameters !

! (Angstroms and Degrees) !

-------------------------- --------------------------

! Name Definition Value Derivative Info. !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

! R1 R(1,2) 1.1935 -DE/DX = 0.0004 !

! R2 R(1,3) 1.1935 -DE/DX = 0.0004 !

! R3 R(1,4) 1.1935 -DE/DX = 0.0004 !

! A1 A(2,1,3) 120.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A2 A(2,1,4) 120.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! A3 A(3,1,4) 120.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

! D1 D(2,1,4,3) 180.0 -DE/DX = 0.0 !

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

GradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGradGrad

The 'YES' below "Item" indicates that the forces are converged, and that the optimisation has been successful.

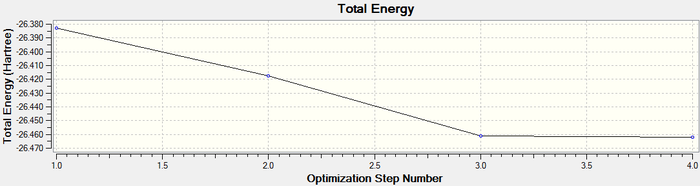

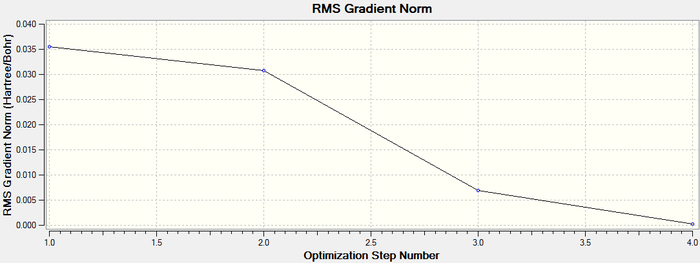

Once it is was confirmed that the molecule had converged it was possible to retrieve a graphical representation for the energy of the molecule at each stage of the optimisation and the gradient of the energy of the molecule.

The graphs obtained are shown below:

The Total Energy curve shows how Gaussian is changing the nuclear position of the Boron and Hydrogen atoms in order to find the minima on the PES curve.

The second graph is the Root Mean Square Gradient, and shows the gradient going to zero as we approach the minimum.

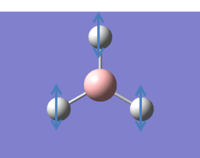

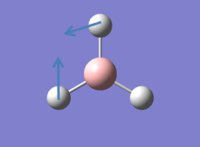

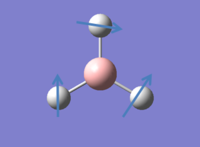

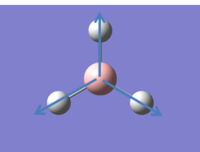

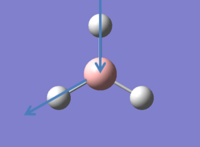

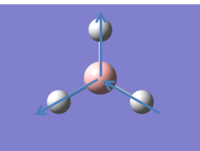

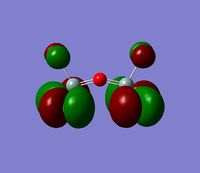

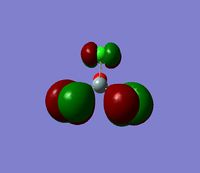

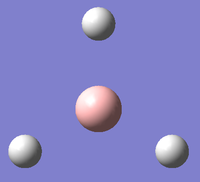

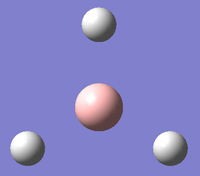

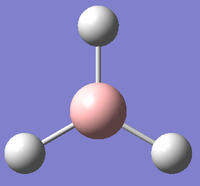

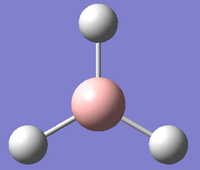

GaussView 5.0.9 allows the different structures of BH3 throughout the optimisation process to be viewed. These are shown below:

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 |

|  |  |  |

It can be noted here that the first structure doesn't have any bonds. This leads us to an interesting question about how we should define a bond in computational chemistry. In theoretical analysis is usually suffices to say that a bond is a force of attraction that hold together atoms in an element or compound. However, in computational chemistry exact parameters must be given for the existence of a bond. This is by no means an easy task, and teh length of an 'average' bond may vary between organic and inorganic systems. (Often bonds in inorganic molecules are much longer than bonds in organic molecules). This means that although Gaussian can give a good approximation about where bond in molecules may be, it is always essential to scrutinise computational results with chemical intuition and theoretical knowledge.

BH3 Frequency

Frequency optimisations must be carried out on a fully optimised structure.

To perform the calculation the following critera were selected in the Gaussian calculation setup:

- Job Type: Frequency

- Additional key words: pop=(full,nbo)

After the calculation had run is was checked by viewing the summary file and checking that the energy was the same as for the optimisation. (In this case, it was, at -26.46au)

The .log or real output file was then viewed.

Low frequencies --- -66.7625 -66.3592 -66.3589 -0.0020 0.0031 0.2123

Low frequencies --- 1144.1483 1203.6413 1203.6424

Harmonic frequencies (cm**-1), IR intensities (KM/Mole), Raman scattering

activities (A**4/AMU), depolarization ratios for plane and unpolarized

incident light, reduced masses (AMU), force constants (mDyne/A),

and normal coordinates:

1 2 3

A" E' E'

Frequencies -- 1144.1483 1203.6413 1203.6424

Red. masses -- 1.2531 1.1085 1.1085

Frc consts -- 0.9665 0.9462 0.9462

IR Inten -- 92.8665 12.3148 12.3173

Atom AN X Y Z X Y Z X Y Z

1 5 0.00 0.00 0.16 0.00 0.10 0.00 -0.10 0.00 0.00

2 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 0.00 0.08 0.00 0.81 0.00 0.00

3 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 -0.38 -0.59 0.00 0.14 0.38 0.00

4 1 0.00 0.00 -0.57 0.38 -0.59 0.00 0.14 -0.38 0.00

The two lines labled 'Low frequencies' show the motions of the center of mass of the molecule that correspond to the 3N-6 vibrational frequencies all molecules possess. The first 'Low frequencies' row shows much lower values than the second row which is what we would expect.

It is possible to consider all the vibrations of BH3 in GaussView by viewing animated diagrams. There 6 different vibrations which are tabulated below:

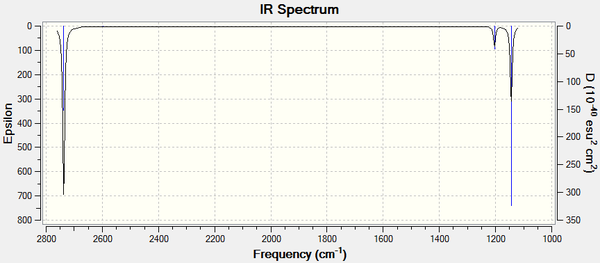

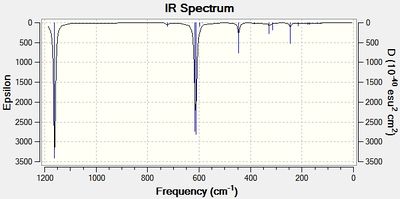

In addition to the animations shown above an IR spectrum can also be observed in GaussView, shown below:

Although there are obviously 6 vibrations, there are only 3 distinct peaks because 2x2 vibrations have the same stretching frequency, 2 at 1203.64cm-1 and 2 at 2737.44cm-1 as a results of having the same point group symmetry. There is also a stretching frequency that has an intensity of 0 at 2598.2cm-1 and so this is not observed on the IR spectrum. This leaves 3 visible peaks as shown on the spectrum above.

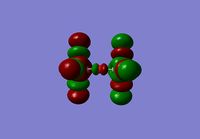

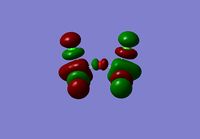

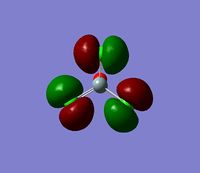

BH3 Molecular Orbitals

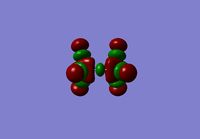

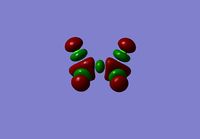

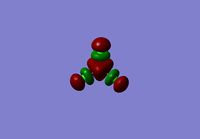

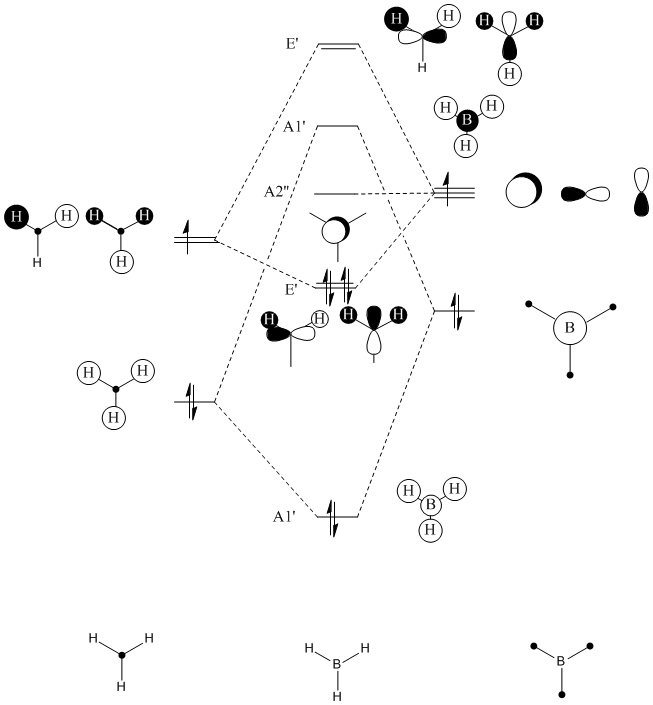

Gaussian can be used to compute quantitative MO's derived from calculations that consider the electronic structure of the molecule. These MO's can be compared to qualitative MO's that are drawn using MO theory diagrams.

Lets begin by drawing the qualitative MO diagram, and then Gaussian will be used to compute the quantitative MOs for comparison.

For quantitative analysis using Gaussina, the optimised BH3 molecule was used. To perform the calculation the following critera were selected in the Gaussian calculation setup:

Job Type: Energy NBO: Full NBO Additional key words: pop=full

The calculation was run on the scan server and deposited in the chemical database "D-space" - [2]

The 'Edit MOs' option was selected in GaussView and the occupied orbitals were viewed under the 'visualise' tab.

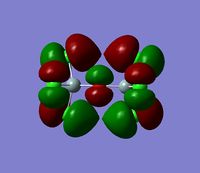

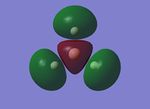

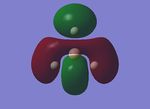

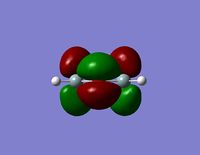

The 7 computed MO's are compared to the qualitative MO's below:

| Orbital | A1' | E' | E | A2 | A1' | E' | E1' |

| MO Diagram MO |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Gaussian MO |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

The best way of showing that the qualitative and quantitative methods of orbital representation are in good agreement is simply by showing how easy it is to match the qualitative drawn MO images to the quantitative orbital images produced by Gaussian just 'by eye'. There is a clear correlation between the molecular orbital shapes, sizes and phases. Although the calculated orbitals do not necessarily correspond directly to the 's', 'p' and 'd' shapes that are used in the molecular orbital diagram, the distinguishing and important features such as presence of nodes and phase pattern of the orbitals are clearly and accurately exemplified in both methods.

Therefore it can be concluded that molecular orbital diagrams are a very useful tool that enables accurate analysis of the key features of molecular orbitals. However, if we wish to know more about how orbital shapes might be affecting the behavior of molecules, computational methods could provide a more useful insight.

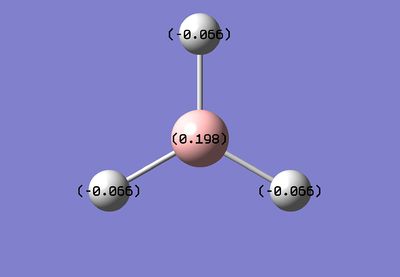

BH3 Charge Distribustion (NBO Analysis)

It is possible to use GaussView to look at the cahrge distribution across the molecule. We have already seen in the 'summary' file that there is no dipole, but this feature enables us to see exactly how the charge is spread across the molecule. As expected, the lewis acidic Boron is positively charged and is surrounded by negatively charged hydride ions.

These are useful pictorial representations of the charge distribution in BH3, however, it is possible to obtain even more information about the Natural Bond Orbitals (NBO's) by looking at the .log file.

The "Summary of Natural Population Analysis:" section of the .log file is shown below:

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.19785 1.99962 2.80253 0.00000 4.80215

H 2 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

H 3 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

H 4 -0.06595 0.00000 1.06582 0.00013 1.06595

=======================================================================

* Total * 0.00000 1.99962 5.99998 0.00040 8.00000

The numbers under the "Natural Charge" heading correspond to the ones shown in the images above.

But by looking at the .log file it is also possible to gleam information about the electron density is shared across specific 'atomic like' orbitals:

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.98096) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 46.65%) 0.6830* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 53.35%) 0.7304* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0005

2. (1.98096) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 46.65%) 0.6830* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 53.35%) 0.7304* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0005

3. (1.98096) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 46.65%) 0.6830* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 53.35%) 0.7304* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0005

4. (1.99962) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

From this information it is possible to see the s and p character of the bond.

The first 3 bonds are all B-H bonds with 33.33% s character and 66.66% p character. It can also be seen that in these bonds B is contributing 46.65% to the bond and the hydrogen is contributing 53.35%. This corresponds to sp2 hybridisation.

The 4th bond is the s atomic orbital of boron (100% s character) and the 5th bond corresponds to the lone pair of electrons in the Boron orbital. It is expected that this would be a p orbital but on this occasion it has been computed as another s orbital. The exact reason for this, on this occasion, is unknown and reminds us that computational methods are useful guides in chemistry but do not always give 100% accurate or truthful results.

The section titles 'Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis' shows mixing between the MO's. Since there is no mixing in BH3 this information is here purely to demonstrate what such analysis would look like:

Normal 0 false false false EN-GB X-NONE X-NONE

Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis

Threshold for printing: 0.50 kcal/mol

E(2) E(j)-E(i) F(i,j)

Donor NBO (i) Acceptor NBO (j) kcal/mol a.u. a.u.

==============================================================================================

within unit 1

1. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2 / 14. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 3 3.54 0.51 0.038

1. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2 / 15. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 4 3.54 0.51 0.038

2. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3 / 13. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 2 3.54 0.51 0.038

2. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3 / 15. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 4 3.54 0.51 0.038

3. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4 / 13. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 2 3.54 0.51 0.038

3. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4 / 14. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 3 3.54 0.51 0.038

4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 10. RY*( 1) H 2 0.59 7.71 0.060

4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 11. RY*( 1) H 3 0.59 7.71 0.060

4. CR ( 1) B 1 / 12. RY*( 1) H 4 0.59 7.71 0.060

The section "Natural Bond Orbital (Summary)"Shows the energy and population of the B-H bonds, and the boron lone pair (B(LP*)):

Normal 0 false false false EN-GB X-NONE X-NONE

Natural Bond Orbitals (Summary):

Principal Delocalizations

NBO Occupancy Energy (geminal,vicinal,remote)

====================================================================================

Molecular unit 1 (H3B)

1. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2 1.98096 -0.38731 14(g),15(g)

2. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3 1.98096 -0.38731 13(g),15(g)

3. BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4 1.98096 -0.38731 13(g),14(g)

4. CR ( 1) B 1 1.99962 -6.76561 10(v),11(v),12(v)

5. LP*( 1) B 1 0.00000 0.74239

6. RY*( 1) B 1 0.00000 0.42448

7. RY*( 2) B 1 0.00000 0.42448

8. RY*( 3) B 1 0.00000 -0.08090

9. RY*( 4) B 1 0.00000 0.43039

10. RY*( 1) H 2 0.00013 0.94934

11. RY*( 1) H 3 0.00013 0.94934

12. RY*( 1) H 4 0.00013 0.94934

13. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 2 0.01903 0.12590

14. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 3 0.01903 0.12590

15. BD*( 1) B 1 - H 4 0.01903 0.12590

-------------------------------

Total Lewis 7.94249 ( 99.2812%)

Valence non-Lewis 0.05710 ( 0.7138%)

Rydberg non-Lewis 0.00040 ( 0.0050%)

-------------------------------

Total unit 1 8.00000 (100.0000%)

Charge unit 1 0.00000

NBO analysis is useful since it breaks the delocalised MO picture down into familiar orbital explanations such as hybridization and multi-electron/center bonds, which can be useful in aiding analysis and explanations of bonding in molecules.

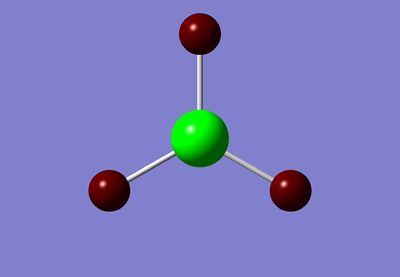

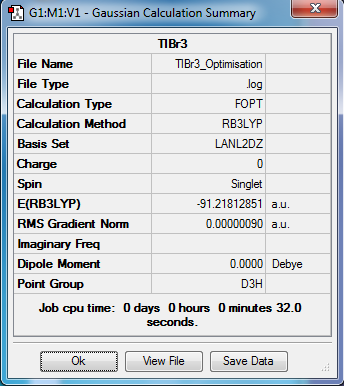

TlBr3 Analysis

TlBr3 Optimisation

TlBr3 was drawn in Gaussian and the point group was strictly restricted to D3h to ensure the vibrational analysss was performed without any problems.

The Gaussian Calculation was set up to run in the following way:

- Method: B3LYP

- Basis set: LanL2DZ (a medium level basis set that used psuedo potentials on heavier atoms)

- Type of Calculation: OPT

The optimisted molecule was then calculated. See [3]

- The optimised Tl-Br bond distance is: 2.65Â

- The optimised Br-Tl-Br bond angle is: 120.0°

The summary information is shown below:

TlBr3 Frequencies and Discussion

It is possible to confirm TlBr3 is an energy minima by frequency analysis.

The Gaussian Calculation was set up to run in the following way:

- Method: B3LYP

- Basis set: LanL2DZ (a medium level basis set that used psuedo potentials on heavier atoms)

- Type of Calculation: FREQ

The same method must be used for both calculations since the same level of accuracy must be employed for both calculations. This will mean the results obtained using the frequency calculation will be accurate wrt the optimisation. If a low level optimisation is done followed by a very accurate frequency calculation, the minima detected may not me the true PES minima.

It is necessary to perform frequency analysis because this enables verification that the optimisation was successful and the true energy minima was found. This is done by checking that there are no negative frequencies reported, as this would suggest that the minima found by the optimisaition was not the true minima of the molecule.

By looking at the .log file it is possible to see that the "Low frequencies" for TlBr3 are:

Normal 0 false false false EN-GB X-NONE X-NONE Low frequencies --- -3.4213 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9367 3.9367 Low frequencies --- 46.4289 46.4292 52.1449

The lowest "real" normal mode is 46.43cm-1.

The optimised Th-Br bond distance was found to be 2.65Â. In a paper studying the optimised bond lengths of aqueous TlX3 compounds the Tl-Br bond length was reported as 2.5Â[2]. This shows a reasonable correlation between the computed value and experimental values.

In some structures gaussview does not draw in the bonds where we expect, does this mean there is no bond? Why?

As explained in section 1, often bonds in inorganic molecules are longer than bonds in organic molecules. This means that sometimes Gaussian does not recognise certain atoms as being bonded as they are too far away from each other, or outside of Gaussian's programmed 'max bond length' parameter.

A bond is usually defined as a force of attraction that hold together atoms in an element or compound. When orbital theories can be employed using 'bonds' as a theoretical tool becomes less useful. Bonds are just areas of high electron density, or areas where the force of attraction between atoms is high. A more correct way of analysing molecules is by looking at the molecular orbitals to determine how the molecule may react based on its orbital size, shape, overlap and charge density.

MO (CO)4L2 Analysis

MO (CO)4L2 Optimisation

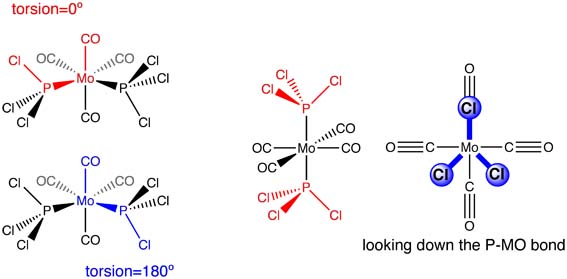

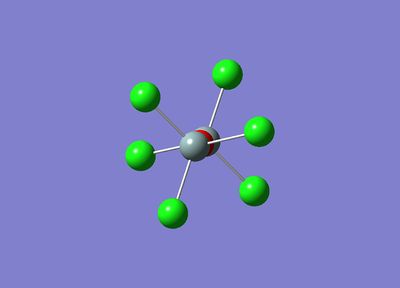

The ground state structures of cis and trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 were optimised.

To perform the calculation the following critera were selected in the Gaussian calculation setup:

- Job Type: Optimisation

- Method: B3LYP

- Psuedo-potential: LANL2MB

- Additional key words: opt=loose

The calculations were run on the scan server and deposited in the chemical database D-Space.

Cis MO (CO)4L2 LANL2MB: [4]

Trans MO (CO)4L2 LANL2MB: [5]

This is a low level calculation and gives a preliminary optimisation of the molecule. It returns fairly accurate values for the bond lengths and angles but doesn't give a very reliable description of the dihedral angle.

If the molecule is not optimised from the right starting orientation Gaussian may find a minima on the potential energy surface that is not the real, or lowest energy minima of the molecule - Gaussian finds the closest minima only. This means that is is necessary to manually position the molecule in a position close to the optimum structure before any further calculations are performed.

For the cis conformer: One Cl atom points parallel to the axial bond, and one Cl atoms on the opposite group points in the opposite direction:

For the trans conformer: Both PCl3 groups are eclipsed, one Cl of each group lies parallel to one Mo-C bond.

From these conformers, a second optimisation was run.

To perform the calculation the following critera were selected in the Gaussian calculation setup:

- Job Type: Optimisation

- Method: B3LYP

- Psuedo-potential: LANL2DZ

- Additional key words: int=ultrafine scf=conver=9

This is a more accurate optimisation calcualtion that includes psuedo-potentials for the heavier atoms.

The calculations were run on the scan server and deposited in the chemical database D-Space.

Cis MO (CO)4L2 LANL2DZ: [6]

Trans MO (CO)4L2 LANL2DZ: [7]

MO (CO)4L2 Frequencies

To perform the frequency calculation the following new critera were selected in the Gaussian calculation setup (with all other criteria remaining the same as for the optimisation):

Job Type: Frequency Additional key words: int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 The calculations were run on the scan server and deposited in the chemical database D-Space.

Cis MO (CO)4L2 Frequancy: [8]

Trans MO (CO)4L2 Frequency: [9]

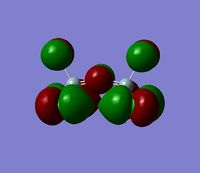

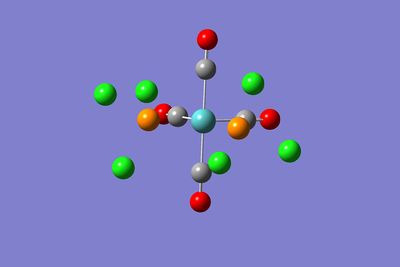

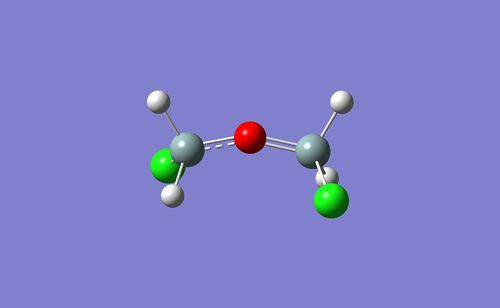

The structures of the two optimised isomers are shown below:

|  |

Comparison of Computed date to literature values

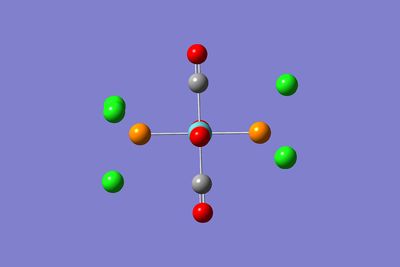

The summary output files for the two isomers gives the following information

Mo Cis Complex Frequency File Name = csw_cis_MoFrequency File Type = .fch Calculation Type = FOPT Calculation Method = RB3LYP Basis Set = LANL2DZ Charge = 0 Spin = Singlet Total Energy = -623.57707194 a.u. RMS Gradient Norm = 0.00000414 a.u. Imaginary Freq = Dipole Moment = 1.3100 Debye Point Group =C1

Trans Mo Complex Frequency File Name = csw_trans_MoFrequency File Type = .fch Calculation Type = FREQ Calculation Method = RB3LYP Basis Set = LANL2DZ Charge = 0 Spin = Singlet Total Energy = -623.57592189 a.u. RMS Gradient Norm = 0.00000847 a.u. Imaginary Freq = Dipole Moment = 0.0325 Debye Point Group = C1

Geometry

Comparison of relevant geometric parameters from the optimised geometries and experimental literature values.

| Bond | Cis (with P bond Trans) Gaussian Å | Cis (with P bond Trans) Literature Å | Cis (with P bond Cis) Gaussian Å | Cis (with P bond Cis) Literature Å |

| Mo-C | 2.01 | 2.06 | 2.05 | 1.97 |

| C=O | 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| P-Cl | 2.23 | - | 2.24 | - |

| Mo-P | n/a | n/a | 2.51 | 2.58 |

| Bond | Trans Gaussian Å | Trans Literature Å |

| Mo-C | 2.06 | 2.01 |

| C=O | 1.17 | 1.17 |

| P-Cl | 2.24 | - |

| Mo-P | 2.45 | 2.50 |

From this table it is possible to see that the Mo-C bonds in the cis complex are slightly shorter than the Mo-C bonds in the trans complex. A possible reason for this could be due to the trans effect where, in the cis complex, the CO ligands are trans to the P ligands. Since the P groups contain negative Cl atoms, they will have an electron with drawing effect. This in turn leads to an increase in back bonding from the C to the Mo and hence a stronger bond. This argument is supported since the C=O bond in the cis complex is slightly longer than the C=O bond in the trans complex. This is due to the fact that the increased back-bonding from C to Mo weakens the C=O bond.

Energy

| Cis Isomer | Trans Isomer |

| -623.5771 a.u | -623.5759 a.u. |

The cis isomer is seen to be slightly more stable than the tans isomer. The difference in energy is -1.2*10^-3 a.u which is 3.15 KJ/mol.

Comparison with literature values shows that the cis isomer actually isomerises to the trans isomer when left at room temperature. [8]. This suggests that since the energy difference between the two isomers is so small, the LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and associated basis set are not quite accurate enough. The P atom still only has basis sets for valence s and p orbital functions, however, P likes to be hypervalent, (to use it's low lying dAOs).

It is possible to add dAO function manually by adding extra basis set.

This is done by editing the command line and also adding code to the end of the document:

# opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 extrabasis (blank line) P 0 D 1 1.0 0.55 0.100D+01 **** (blank line)

By performing analysis by using the more accurate dAO function, it can be seen that the trans isomer is now calculated as the most stable [10] [11]:

One of the benefits of computational chemistry is that molecules can be fine tuned by stabilising the structurally more efficient isomer. If the L=PR3 ligand was made into a bidentate ligand then perhaps the most stable isomer would differ. Unfortunately, time contraints mean that it will not be possible to explore this in this report.

Frequencies

There were no very low/negative frequencies so it can be concluded that the optimisations of both molecules were successful.

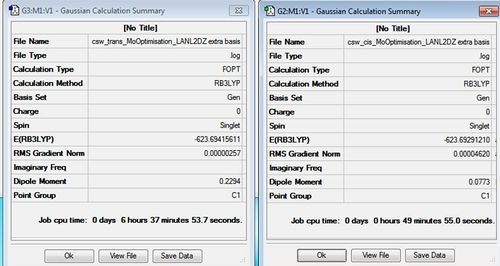

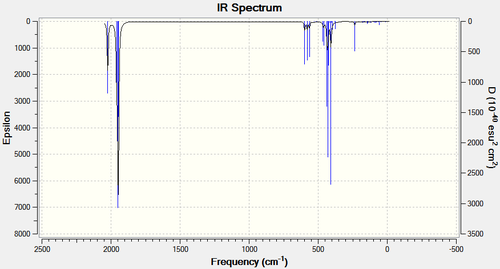

From Gaussian it can be seen that the cis isomer has 4 vibrational modes in the carbonyl stretching region: 1945cm-1 (b2), 1949cm-1 (b2), 1958cm-1 (a1) and 2023cm-1 (a1):

and that the trans isomer has 2 vibrational modes:

1950cm-1, 1951cm-1:

The IR spectra for both complexes can also be viewed using Gaussian:

From the IR spectra it is possible to see one peak in the carbonyl region of the trans-IR spectrum, and 3 distinct peaks in the carbonyl region of the cis spectrum. This is not what would be predicted from looking at the molecules, (2 stretching frequencies would be expected for the trans complex, and 4 for the cis complex). This is possible due to the fact that some of the stretching frequencies in both molecules are extremely similar and therefore do not show up as distinct peaks on the IR spectrum.

These values are fairly comparative with literature values for cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2.[9] and so it can be concluded that the Gaussian calculations were a good representation of experimental results in this case.

Mini Project

Siloxanes: Introduction

Siloxanes are a composed from the sub-unit R2SiO. The backbone of the molecule consists of Si-O bonds, whilst the R groups can be hydrocarbon groups or halogen (mainly chlorine) groups. Siloxanes are commonly polymerised to silicones which are industrially very useful due to their flexible properties.

In Dr Paul Lickiss's Second Year lecture course on main group chemistry, the interesting bonding nature of Silicon and Oxygen was discussed.

Siloxane oils, Elastomers (rubbers) or resins can all be obtained from polymerisation reactions of siloxanes. They are extremely stable and can withstand high temperatures yet retain their rubber like properties even at low temperatures.

These outstanding properties arise because of the flexibility of the Si–O–Si link. This has been rationalised through delocalisation of the lone pairs on oxygen into available orbitals on Si. This reduces the directionality of the Si–O bond and hence makes the structure more flexible.

However, it is still not entirely known whether the lone pairs on the oxygen are delocalised into the d or σ* of the silicon.

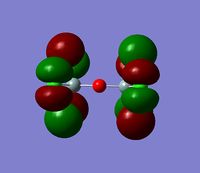

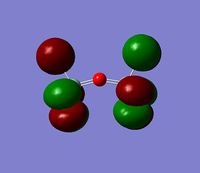

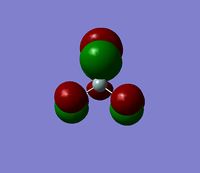

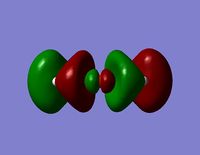

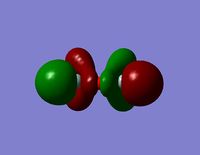

Orbital diagrams for the two scenarios are shown below.

|  |

In this mini project simple siloxane molecules will be analysed using computational methods in order to understand more about the nature of the Si-O bond.

It will also be interesting to consider what chemical features of siloxanes / silicones influence the extent of elasticity observed. A good starting point for this analysis will be via considering whether the R groups of siloxanes influence the Si-O bond.

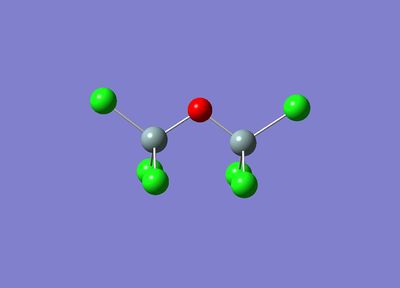

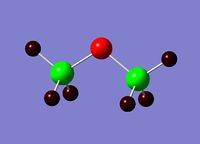

Cl3SiOSiCl3

The molecule Cl3SiOSiCl3 has been chosen as a starting molecule since is possesses the Si-O-Si bond of interest, but at the same time the overall size of the molecule is kept to a minimum by using Cl atoms as R groups (instead of eg. CH3 groups).

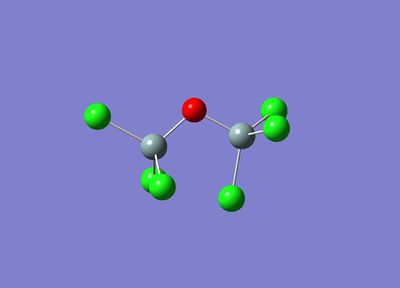

Since Gaussian only computes local minima of molecules, two conformers of Cl3SiOSiCl3 were drawn in Gaussian as starting molecules. One with the Cl3 groups staggered and one with the Cl3 groups eclipsed.

These are shown below:

|  |

Preliminary optimisations of the two conformers were submitted to the scan server in order to find the lower energy conformer. This was done in order to make sure that the real PES minima was found, and used going forward in further calculations.

Since there are relatively 'heavy' Cl atoms present in this molecule, it is sensible to use psuedo-potentials to model them. Psuedo-potentials use predetermined models for the behavior (or force field) of the inner electrons of atoms. This reduces the computing time as only calculations on the valence electrons are needed. Since the psuedo-potentials have been pre-computed, and since valence electrons almost entirely influence the behavior of atoms in molecules, accuracy is not compromised but a significant amount of time is saved.

The psuedo-potentials are applied my manually editing the input .log file and assigning either a normal basis set or psuedo potential basis set to all the atoms present.

The Gaussian Calculation was set up to run in the following way:

- Method: B3LYP

- Basis set: Gen

- Type of Calculation: OPT

The .log file was then opened and edited to input the psuedo potentials. The final .log file is shown below:

# opt b3lyp/gen geom=connectivity gfinput pseudo=cards Cl3SiOSiCl3 (Eclipsed) 0 1 O -0.56144067 1.31355930 0.00000000 Si -1.17230722 3.03859323 0.00000000 Si 1.26855628 1.31355822 -0.00334494 Cl -0.45281896 4.05718886 1.76363250 Cl -0.45281823 4.05718803 -1.76363268 Cl -3.33230695 3.03750759 0.00000026 Cl 1.98855681 -0.72290902 -0.00270212 Cl 1.99177790 2.33348722 1.75798845 Cl 1.98532961 2.33009523 -1.76926921 1 2 1.0 3 1.0 2 4 1.0 5 1.0 6 1.0 3 7 1.0 8 1.0 9 1.0 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cl 0 LanL2MB **** Si O 0 3-21G(d) **** Cl 0 LanL2MB

Note that the 3-21G basis set was set to include d orbitals. This was because the Silicon d-orbitals are actually unoccupied, but it is thought that they may play a part in the Si-O bond. It was therefore necessary to input to Gaussian that the Si d orbitals should be included in the calculation even though they are initially unoccupied.

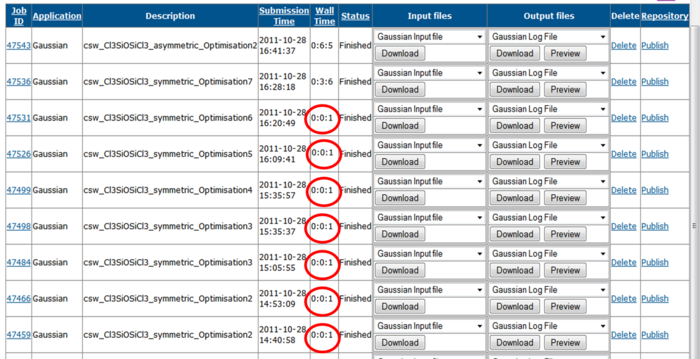

The calculation was submitted to the scan server but failed. Minor modifications to the .log input file were made, such as:

- Trying to code for the 3-21G(d) basis set using 3-21G*, an alternative method of inputting d-orbitals.

- Using the 3-21G(d,p) basis set

- Double checking that the normal basis sets and pseudo-potential basis sets had been coded correctly

- Redrawing the Cl3SiOSiCl3 conformers and making new .log input files

Neither of these alterations led to a successful optimisation calculation (see below) and so the Gaussian 09 User Guide on the Gaussian website was used to look for a reason why the calculations were not proceeding.

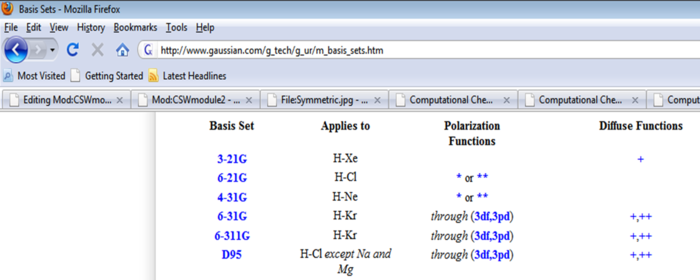

By looking at the information on basis sets [12], it was discovered that the 3-21G basis sets do not have polarisation functions. The polarisation functions enable empty d and p orbitals to be computed even though they are unoccupied. This is precisely what is needed for this calculation. The unoccupied Si d orbitals need to be computed as it is thought that the oxygen lone pair delocalises into the Si d orbitals.

Therefore, an initial low level optimisation is not actually possible for Cl3SiOSiCl3 and it was decided the best course of action was to perform a medium level optimisation, LANL2DZ straight away where the 6-31G(d) basis could be correctly employed and successfully computed.

The new input .log file is shown below:

# opt b3lyp/gen geom=connectivity gfinput pseudo=cards Cl3SiOSiCl3 (Symmetric) 0 1 O -0.56144067 1.31355930 0.00000000 Si -1.17230722 3.03859323 0.00000000 Si 1.26855628 1.31355822 -0.00334494 Cl -0.45281896 4.05718886 1.76363250 Cl -0.45281823 4.05718803 -1.76363268 Cl -3.33230695 3.03750759 0.00000026 Cl 1.98855681 -0.72290902 -0.00270212 Cl 1.99177790 2.33348722 1.75798845 Cl 1.98532961 2.33009523 -1.76926921 1 2 1.0 3 1.0 2 4 1.0 5 1.0 6 1.0 3 7 1.0 8 1.0 9 1.0 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cl 0 LanL2DZ **** Si O 0 6-311G(d) **** Cl 0 LanL2DZ

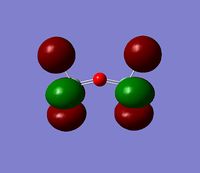

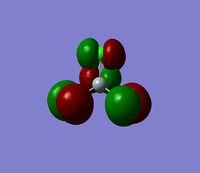

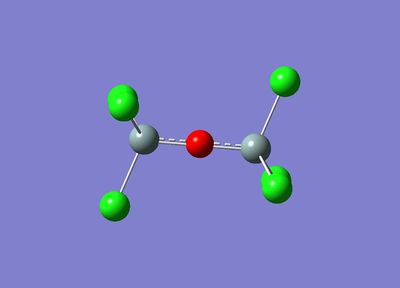

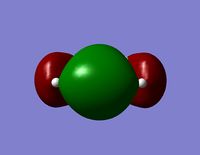

After this adjustment, the Gaussian calculation ran successfully and produced the following optimised molecule:

|  |

The initial optimisation shows 2 interesting features that are exemplified in the images above.

The first is that both the eclipsed and staggered conformers are optimised to a staggered conformer. This shows that this is the most stable conformer and the lowest point on the PES.

The second point of interest is that the optimised molecule is linear. This is a slightly surprising result since silicon polymers are generally thought to exhibit a 'zig-zag' structure with bond angles of 130° between the silicon and oxygen atoms.

This means that either the input .log file was not accurate enough for Gaussian to compute a correct result, or, that the structure of the small Cl3SiOSiCl3 molecule is actually linear.

In order to investigate further, a longer molecule (with an extra Si-O unit) was optimised in Gaussian. However, this optimisation did not recover a 'zig-zag' molecule either, and instead the conformation shown below:

For some further guidance with this problem, some existing research on siloxane bonding was read. In an article written by Heinz Iberhammer and James E. Boggs [10] which investigated the importance of (p-d)π bonding in the siloxane bond it was noted that:

"In many molecules experimental oxygen bond angles are reproduced satisfactorily only when polarization functions are added (4-21* basis set). These polarization functions are constructed in the same way as the Si (d) functions. Without polarization functions the optimized COSi bond angle in H3COSiH3 is larger by 8.2’ than the experimental value, and the SiOSi skeleton in disiloxane comes out to be linear. In disilyl peroxide the oxygen polarization functions do not change the OOSi bond angle very much but have a large effect on the SiOOSi dihedral angle. "

With this as a source of inspiration, and the knowledge that the optimised Cl3SiOSiCl3 molecule should infact contain a SiOSi angular, not linear, bond, extra polarisation functions were added to the oxygen p orbital in the initial .log input file.

# opt b3lyp/gen geom=connectivity gfinput pseudo=cards Cl3SiOSiCl3 (Symmetric) 0 1 O -0.56144067 1.31355930 0.00000000 Si -1.17230722 3.03859323 0.00000000 Si 1.26855628 1.31355822 -0.00334494 Cl -0.45281896 4.05718886 1.76363250 Cl -0.45281823 4.05718803 -1.76363268 Cl -3.33230695 3.03750759 0.00000026 Cl 1.98855681 -0.72290902 -0.00270212 Cl 1.99177790 2.33348722 1.75798845 Cl 1.98532961 2.33009523 -1.76926921 1 2 1.0 3 1.0 2 4 1.0 5 1.0 6 1.0 3 7 1.0 8 1.0 9 1.0 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cl 0 LanL2DZ **** Si O 0 6-311G(d,p) **** Cl 0 LanL2DZ

This calculation, however, again returned a liner molecule. Given that the paper mentioned above discusses H3SiOSiH3, it is not certain whether this is the actual optimisation for Cl3SiOSiCl3 or not at this stage.

In order to tackle this problem in a more methodical manner, it seems sensible to optimise the simpler siloxane H3SiOSiH3, which we know should have a bent geometry. Although this means that the initial aim to study the effect of substituting the Cl 'R' groups will be slightly compromised in the short term, it will eradicate the need to use pseudo-potentials and simplify the calculation significantly. It is hoped that a more representative picture of the Si-O-Si bonding orbitals will be obtained using this approach.

Then, I will return to Cl3SiOSiCl3 and will be able to look into the bonding and geometry of this molecule with H3SiOSiH3 as a reference.

H3SiOSiH3

The H3SiOSiH3 molecule was sent to scan with the following command line in the .log file

# b3lyp/6-31g(d,p) geom=connectivity

This uses a normal basis set that includes the d and p polarisation functions but does not use any psuedo-functions.

The molecule was optimised successfully and published on the Chemistry Database D-Space: [13]

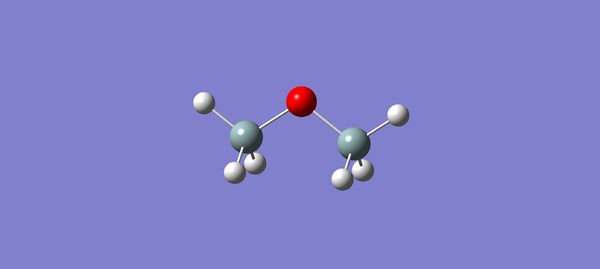

As seen in the image below, the Gaussian optimisation of H3SiOSiH3 now shows the expected conformation.

The assumed successful optimisation of this molecule suggests that there was a problem defining the d and p orbital polarisation functions whilst using psuedo-potential basis functions. This will be returned to later in the report in order to return to the original aim of the experiment.

However, in the mean time, in to gauge an idea of the bonding in this simple molecule, an energy calculation was run on the optimised molecule. (See command line below.)

# b3lyp/6-31g(d,p) geom=connectivity

The calculation was successfully run on the scan server and the file published to the chemistry database in D-space: [14]

Geometry

To check that this optimisation was successful, the geometric parameters were compared to literature values:

| Geometric Feature | Calculated Value | Literature Value |

| Si-O Bond | 1.83Å | 1.67Å |

| Si-H Bond | 1.47Å | 1.47Å |

| Si-O-Si Bond Angle | 109.5° | 110.6° |

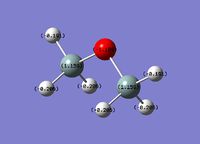

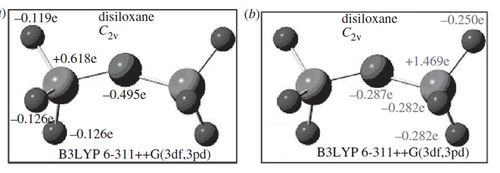

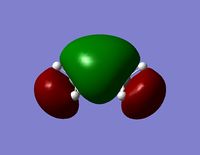

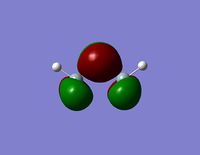

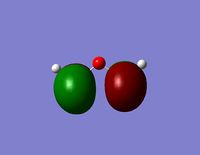

Charge Distribution

Charge Distribution analysis was also performed for comparison to literature values on this occasion just to confirm that this structure was infact correctly optimised.

|  |

Alternative charge distribustion analysis was found in the literature, and although, here, different methods (not NBO) are used, it is still possible to see that the relative charge distribution across the molecule is very similar with the 4 hydrogen atoms pointing down being slightly more negative than the 2 hydrogen atoms pointing up. The oxygen is highly negatively charged and the silicon highly positively charged as expected.

This analysis and comparison to literature values helps verify that the optimisation has been correctly performed on this occasion.

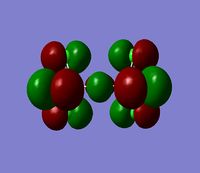

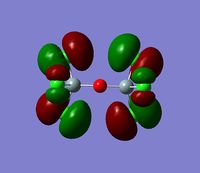

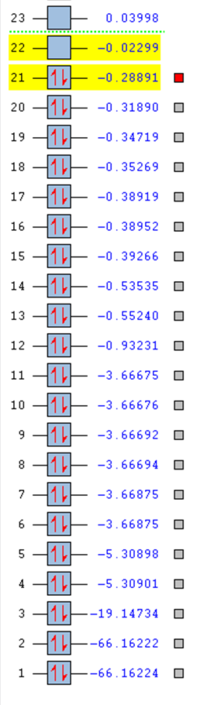

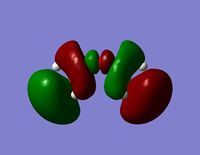

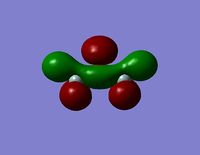

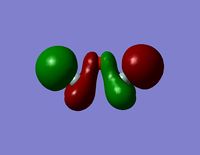

MO Analysis

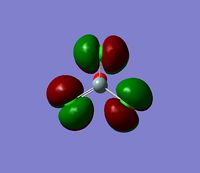

To get an idea of the molecular orbital shapes, images of the LUMO+2 through to the HOMO-4 are shown below:

| Orbital | View from Above | View from Side |

| LUMO +2 |  |  |

| LUMO +1 |  |  |

| LUMO |  |  |

| HOMO |  |  |

| HOMO -1 |  |  |

| HOMO -2 |  |  |

| HOMO -3 |  |  |

| HOMO -4 |  |  |

Analysis

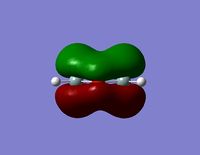

In the following analysis the following axial systems is used as a tool for discussion:

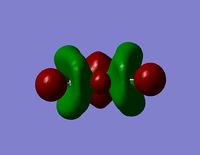

- The HOMO-1 reveals a very interesting molecular orbital shape. The s- orbitals of the lower hydrogen’s seem to be interacting across the molecule (in the y-plane) which could explain why this particular conformer is the most stable one according to the Gaussian optimisation. The lower lobe of the oxygen p orbital in the z-plane is clearly interacting with the upper 2 hydrogen atoms. This leads to a molecular orbital shape that would not usually be predicted through the LCAO approach, but that does perhaps help to explain how delocalisation across siloxane molecules takes place. It is generally assumed that delocalisation of the oxygen lone pair into the empty d-orbitals of the silicon atoms is the main reason for siloxanes’ flexible properties. However, this orbital representation highlights the fact that there may be several other orbital factors that contribute to the observed properties of siloxanes. The clear interaction of one of the R groups with the oxygen orbital suggests that R groups are important when considering at least the molecular orbitals of siloxanes, and it could thus be postulated that R groups also influence the properties of siloxanes via electronic / orbital interactions. This can be explored further by altering the R groups to other atoms.

- The HOMO region of the bond shows clear s-character of the 4 lower Hydrogen atoms. The Oxygen atom shows p-like character across the top plane of the molecule. This could potentially lead to interaction between the p-orbitals of the oxygen with the s-orbitals of the hydrogen atoms in a diagonal fashion. The electron density of the HOMO is largely centred about the oxygen. Although there is some overlap into the space surrounding the silicon atoms there is no clear interaction with either of the silicon orbitals.

- Since none of the bonding orbitals reveal any real indication of the suspected d-orbital lap between the Silicon and Oxygen atoms, in order gain some more insightful information the LUMO orbitals can be briefly considered.

- The LUMO shows a large area of virtual electron density situated between the Silicon and the Oxygen atoms. This clearly shows that the silicon and oxygen atomic orbitals are interacting significantly in the formation of the molecular orbital. It can also be noted that the LUMO orbitals are relatively ‘tight’ to the atoms and this leads to a bareness around the molecule that could inhibit the ease of any attacking nucleophiles or electrophiles. This might be a reason why siloxanes are fairly unreactive and can maintain their properties through a large range of temperatures. However, the LUMO does not really provide any insights into the specific type of bonding that may be present between the silicon and oxygen atoms. The only property that this information can allude to is the stability of siloxanes.

- The LUMO+1 reveals are more interesting orbital pattern, which is actually quite similar in terms of shape to the HOMO-2. The large sigma orbitals of the hydrogen atoms are present but are too far away to have any impact on the Si-O bond of interest. The orbital about the silicon spans a similar special area to the 3 hydrogen atoms creating a triangular shape. This is again not what would be expected from a usual LCAO approach but the symmetry is rational considering the shapes of the atoms present. This orbital could explain the geometry of the molecule. However, this orbital diagram does still not reveal information about the possible Si-O interaction. The p-like orbital of the oxygen does not appear to be interacting with the orbitals around the silicon atoms at all.

Since this method seemed to be successful, the same method was applied to ClH2SiOSiH2Cl, where 2 of the hydrogen atoms had been replaced with chlorine atoms.

The psuedo-potential basis functions are again excluded, but this time the optimised file [15] contained an error and revealed a geometry that was almost linear with a Si-O-Si bond angle of 156.37°, compared to the H3SiOSiH3 angle of 109.5°.

This infers that in order to include analysis of Cl containing siloxanes, psuedo-potential basis sets should be employed. However, this returns us to the original challenge of using the correct polarisation functions whilst employing psuedo-potential basis sets.

In order to investigate this problem further, and to see why the presence of chlorine atom R groups might be leading to an unexpected optimisation, the linearly optimised molecule that was computed using both psuedo-potentials and d,p orbital basis sets was reconsidered.

Returning to Cl3SiOSiCl3

- Please note that after the obstacles faced in this mini project, some of the calculations were only run on the afternoon of 1/11/2011. Therefore it took a few hours after the 5pm deadline to finish collecting, uploading and analysing the results for some parts of this section *

The output .log file [16] was viewed to see if there was any obvious error in the file.

The command line correctly read:

# opt b3lyp/gen geom=connectivity gfinput pseudo=cards

and it could also be seen that the file had correctly converged:

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000019 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000010 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001622 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000875 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.274646D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The .log output file also showed that both the oxygen and silicon atoms had been computed with the d-orbital basis set.

In the code below atom 1 is oxygen and atom 2 is Silicon. Only the d-orbital basis sets are shown:

1 0

D 1 1.00 0.000000000000

0.1292000000D+01 0.1000000000D+01

****

2 0

D 1 1.00 0.000000000000

0.4500000000D+00 0.1000000000D+01

An energy calculation was performed on the optimised molecule so that molecular orbital diagrams could be obtained for comparison to the H3SiOSiH3 molecular orbitals: [17]

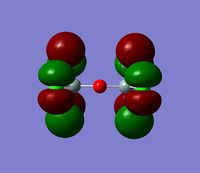

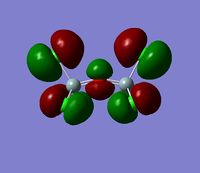

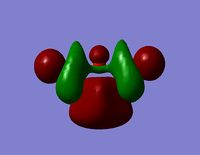

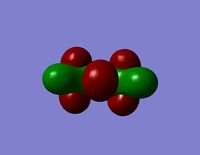

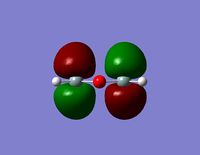

Some of the molecular orbitals are shown below and orbitals of interest compared to equivalent orbitals of H3SiOSiH3 :

Whereas in the H3SiOSiH3 HOMO-1 molecule there was an overlap of the oxygen p orbital across the silicon and onto the upper hydrogen atoms, no such overlap is seen in the Cl3SiOSiCl3 molecule.

This may be partly due to the fact that chlorine is much bigger than hydrogen. However, a more explanatory conclusion might be that because chlorine is so electronegative it is pulling electron density away from the Si-O-Si bond towards the outside of the molecule. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the optimised molecule shows a semi double or delocalised bond across the Si-O-Si bond. (See image above table.) Therefore, it is probable from these results that the reason for the very different orbitals between the two molecules is due to the electronegativity of chlorine. The electron density that can be spread across the Si-O-Si bond when the siloxane R groups are not electronegative is removed when highly electronegative groups, such as chlorine, are used.

It can also be seen from the MO diagrams that from the HOMO-1 and above, all p-orbital character has been removed from the oxygen in Cl3SiOSiCl3 whereas in H3SiOSiH3 the p orbitals of the oxygen are playing a major role in the orbital formation. This again supports the hypothesis that it is the electronegative chlorine atoms that are pulling electron density away from the centre of the molecule to the outside.

This molecular orbital evidence leads to the conclusion that molecular orbital and electronic factors do play a major role in determining the geometry of siloxanes. Although the H3SiOSiH3 orbitals are not clear enough to observe any of the suspected d-orbital overlap, by comparison to the Cl3SiOSiCl3, it can be seen that there is substantially more orbital overlap in the Si-O-Si region which is assisting the bent geometry and possibly it’s flexible nature.

It would be useful to test this hypothesis, that the chlorine atoms pull electron density away from the oxygen and from a semi double bond across the Si-O-Si bond, by performing frequency and NBO analysis, as this could reveal move information about the bonding in the molecules.

Frequency

Frequency optimisations were run for both H3SiOSiH3 and Cl3SiOSiCl3 [18] [19]

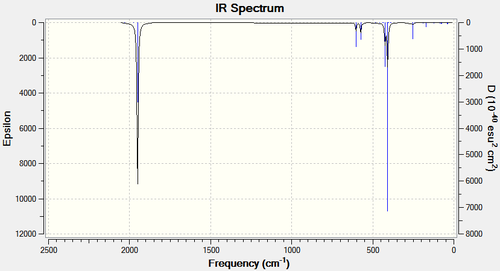

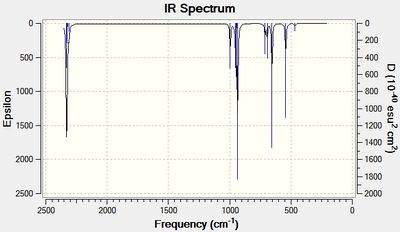

IR spectra for both H3SiOSiH3 and Cl3SiOSiCl3 are shown below:

|  |

There are clear differences between the spectra namely that the H3SiOSiH3 molecule has many more vibrational modes in the region 500-1000cm-1 due to Si-H stretches.

More interestingly, however, are the stretching frequencies of the Si-O bond. In H3SiOSiH3 there is only one Si-O vibrational frequency at 654cm-1. However in Cl3SiOSiCl3 there are 3 different vibrational modes for the Si-O bond, at 611cm-1, 616cm-1 and at 1116cm-1.

Animations for the different Si-O stretching frequencies can be viewed here:

H3SiOSiH3

Cl3SiOSiCl3

It is clear from the animation that the Si-O bond of Cl3SiOSiCl3 behaves in a very different way to the Si-O bond of H3SiOSiH3. The extra stretching frequencies in Cl3SiOSiCl3 support the hypothesis that the Si-O bond in this complex has more of a double bond nature than a single bond nature.

By viewing the animations, it is possible to see that the H3SiOSiH3 bond is much more rigid. Perhaps the overlap of the oxygen p-orbital electrons between the Si atoms (as shown by the MO diagrams) leads to this behavior, and could begin to help explain why Si-O-Si polymers are flexible enough to be industrially useful, but maintain their properties at high and low temperatures by possessing some degree of rigidity in the bond.

Finally a brief NBO analysis of Cl3SiOSiCl3 could help to determine more clearly what the bonding in the molecule is like.

The following NBO analysis was obtained:

Normal 0 false false false EN-GB X-NONE X-NONE

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.98260) BD ( 1) O 1 -Si 2

( 87.31%) 0.9344* O 1 s( 46.05%)p 1.17( 53.91%)d 0.00( 0.04%)

0.0001 -0.6786 0.0018 -0.0001 0.7071

-0.0060 0.1978 -0.0020 -0.0037 0.0000

-0.0038 0.0001 0.0001 -0.0144 0.0121

( 12.69%) 0.3563*Si 2 s( 26.24%)p 2.74( 72.00%)d 0.07( 1.75%)

0.0000 0.0001 -0.5105 -0.0414 0.0070

-0.0001 -0.8354 0.0280 -0.0001 -0.1461

-0.0031 0.0000 0.0027 0.0001 -0.0268

0.0005 0.0001 -0.1114 0.0665

2. (1.98260) BD ( 1) O 1 -Si 3

( 87.31%) 0.9344* O 1 s( 46.05%)p 1.17( 53.91%)d 0.00( 0.04%)

-0.0001 0.6786 -0.0018 0.0001 0.7071

-0.0060 -0.1978 0.0020 0.0037 0.0000

-0.0038 0.0001 -0.0001 0.0144 -0.0121

( 12.69%) 0.3563*Si 3 s( 26.24%)p 2.74( 72.00%)d 0.07( 1.75%)

0.0000 -0.0001 0.5105 0.0414 -0.0070

-0.0001 -0.8354 0.0280 0.0001 0.1461

0.0031 0.0000 -0.0027 -0.0001 -0.0268

0.0005 -0.0001 0.1114 -0.0665

This shows the bonding between the Si and O. As seen, there is both s and p character to the bond, where the oxygen contributed 87.31% to the bond and the silicon 12.69%. The oxygen contributes 53.91% p-character to the bond. This supports the notion that in Cl3SiOSiCl3 the lone pairs of the oxygen are being drawn to the edges of the molecule by the electronegative Cl atoms leading to the double bond observed in the optimised moleucle.

Mini Project Conclusion

The mini-project has first, and foremost, shown how often initial research objectives evolve as data is collected and analysed. This project has shown that when unexpected results arise, a critical evaluation must be undertaken in order to decide whether the unexpected result is due to a computational error or a chemical phenomenon. In this report evaluation of both computational techniques and chemical structure have been considered.

This project aimed to explore the flexible nature of the Si-O bond and what influences its properties. Cl3SiOSiCl3 was chosen as a reasonable sized starting molecule. However, it was soon discovered that optimising this molecule using basic techniques was not an easy task, and several of the optimisations returned error messages. By using the Gaussian website user manual, it was discovered that basis orbitals for silicon p and d orbitals needed to be specifically defined in the basis set since, as they were not occupied in the starting molecule but were thought to participate in bonding in the optimised structure. It was also discovered that only certain basis sets could be used when defining these unoccupied orbitals. By turning to some literature it was also discovered that the best optimisation could be recovered by manually assigning p-orbital basis sets to the oxygen atom.

The optimised structure revealed a linear molecule which was an unexpected result. However, by using molecular orbital, frequency and natural bond analysis and by comparing Cl3SiOSiCl3e to H3SiOSiH3 the results were somewhat rationalised.

The H3SiOSiH3 molecule optimised as theory would predict with a 109° bond angle between the Si-O-Si bond.

In the H3SiOSiH3 molecular orbitals, there was some indication of orbital overlap between the Si and O atoms mainly due to the lone pair of electrons on the oxygen atom interacting with both the silicon atom and the outer hydrogen atoms.

In the Cl3SiOSiCl3 it turned out that the chlorine groups are so electronegative that they pull electron densisty away from the centre of the molecule to the outside. This means that the lone pair of electrons on the oxygen cannot participate in any orbital overlap but instead is pulled across the molecule to form what looks like partial Si-O double bonds. This was verified by the IR analysis and the NBO analysis.

Although there has not been much progress in discovering the exact nature of any overlapping Si-O orbitals, this project has revealed a lot about how Gaussian computes molecules, and also revealed how what can seem like fairly subtle chemical differences between molecules can actually have very large implications for the bonding and geometry.

If there were time it would be interesting to further substitute the R groups with eg. Br, F, OH, CH3 to see whether there was a trend between the electronegativity of the R groups and the type of bonding present in the siloxane.

References

- ↑ http://www.gaussian.com/g_tech/g_ur/k_opt.htm

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ja00123a011

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ Elmer C et Al., Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, pp.3864-3873

- ↑ DOI:10.1021/ja00544a011

- ↑ DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(91)87190-M

- ↑ DOI:10.1016/0009-2614(91)87190-M