Rep:Mod:CSM1006

Abstract

The use of the Gaussview computational program to analyse the mechanisms of pericyclic reactions such as the Cope rearrangement and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition has been explored. The Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene was analysed using the Hartree-Fock method as well as density functional theory (DFT) calculations. It was found that the Cope rearrangement is likely to be a concerted reaction involving a single aromatic-type transition state. Through a comparison of the reaction pathways involving the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures, it was concluded that the reaction pathway involving the 'chair' transition structure is the preferred reaction pathway. The Diels-Alder cycloaddition was analysed at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. The reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene was studied and it was concluded that the reaction was governed by the Woodward-Hoffman rules of orbital symmetry. In the cycloaddition of cyclohexadiene with unsymmetrical dienophiles such as maleic anhydride, it was found that the endo transition structure was more stable than the exo transition structure. However, the reasons for this preference are not clear and are likely to involve stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the endo TS as well as destabilising steric repulsions in the exo TS. Further more in-depth computational studies are required in order to understand the relative importance of these two factors.

Introduction

Pericyclic reactions comprise one of the most important classes of organic reactions. The mechanisms by which these reactions proceed have attracted the interest of many in recent years; however, they have been the subject of much controversy even till this date. Computational studies provide a direct tool for the understanding of the possible intermediates and transition states involved, as well as a powerful method for the interpretation of experimental data, such as activation energies and kinetic isotope effects.[1]

Typically, most computational studies begin with a calculation of the structures of the reactants and products, including an analysis of the lowest energy conformations. Next, the first-order saddle point connecting the reactants and the products is calculated. The most frequently used methods for such studies are the Hartree-Fock and the density functional theory (DFT) methods. Subsequently, intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRC) calculations are also useful for plotting a low energy pathway for the reaction.[1] In the case of more complicated systems, semi-empirical methods which take into account certain approximations can be used to invoke lower computational costs. These methods will be employed in this experiment.

Of the various pericyclic reactions known, Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions and [3,3]-sigmatropic shifts such as the Cope rearrangement have been the most intensively studied. This experiment aims to investigate these two reactions using Gaussview and can thus be divided into two parts. The first part focuses on the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene, where the aim is to locate the low-energy minima and transition structures on the C6H10 potential energy surface, as well as to determine the preferred reaction mechanism. The second part focuses on the Diels-Alder cycloaddition of ethylene and 1,3-butadiene, and the rules of orbital symmetry that govern pericyclic reactions. The factors that govern regioselectivity in Diels-Alder cycloadditions will also be studied through the reaction of cyclohexadiene with maleic anhydride.

The Cope Rearrangement

In 1940, Arthur Cope discovered a reaction which now bears his name.[2] In this exercise, the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene will be studied (Figure 1). This reaction is a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement which involves the migration of an allyl group in a three-carbon system. The mechanism of this rearrangement had been the topic of heated discussion over the past few decades, but it is now widely accepted (Reference? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST))that this is a concerted reaction, involving a single aromatic-type transition state, which is in agreement with the Woodward-Hoffmann rules. The 'chair' and 'boat' have been proposed as possible transition structures, with the 'boat' transition structure lying several kcal/mol higher in energy (Figure 2). This mechanism is supported by Hartree-Fock and DFT calculations, which give good to excellent agreement with experimental results.[3] Consequently, this section of the report discusses the use of Gaussview calculations (Gaussview is actually just the interface used to setup and read the output of the Gaussian program run on the background. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)) to investigate the transition structures of this reaction. The discussion can be split into two parts - firstly, an optimisation of the reactant and product structures; and secondly, an analysis of the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures and hence the preferred reaction pathway.

Optimising the Reactants and Products

As the reactant and product of this Cope rearrangement is both 1,5-hexadiene, it is sensible that calculations of the 1,5-hexadiene structure will give us adequate information about the low-energy conformations in this reaction. In the most approximate sense, 1,5-hexadiene can adopt two general conformations: an anti-periplanar (a.p.p) conformation and a gauche conformation, with respect to the central C-C bond. The investigation started with the optimisation of a 1,5-hexadiene molecule with an "anti" linkage for the central four C atoms. This is approximately equivalent to an a.p.p conformation. The optimisation was performed at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The value for the optimised minimum energy was noted and the molecule was symmetrised to obtain its point group. The same optimisation procedure was repeated for an approximate "gauche" conformation, again at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The results are summarised in Table 1. Upon comparison with the given values for a series of known conformers,[4] these conformers were identified as the anti1 and gauche3 conformers respectively. It can be seen that the gauche3 conformer is lower in energy than the anti1 conformer. (Is this what you expected a priori? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST))

| Conformation | Structure | Point Group | Energy / a.u. | Conformer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Anti" | C2 | -231.69260237 | Anti1 | |||

| "Gauche" | C1 | -231.69266120 | Gauche3 |

Typically, the lowest energy conformation of a molecule is used as a reference for other investigations such as calculations of the activation energies or enthalpies. It cannot be concluded with certainty that the two guess conformations above are the lowest energy conformations of 1,5-hexadiene. Consequently, it is of interest to find out what the lowest energy conformation of 1,5-hexadiene might be, and this can be done by investigating the energies of all the different conformers. 1,5-hexadiene contains three readily rotating C-C bonds, each of which has three rotational minima. This allows for 27 conformations of the 1,5-hexadiene molecule. However, due to symmetry and enantiomeric relationships, only 10 are energetically distinct.[5] These 10 distinct conformers of 1,5-hexadiene were optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory and the results are summarised in Table 2. All experimentally obtained results were cross-checked with the given values[4] and the results are in good agreement with the expected values.

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

Relative Energy/kcal/mol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche1 (J/L) | C2 | -231.68771610 | 3.10 | |||

| Gauche2 (A) | C2 | -231.69166699 | 0.62 | |||

| Gauche3 (D/F) | C1 | -231.69266120 | 0.00 | |||

| Gauche4 (C) | C2 | -231.69153035 | 0.71 | |||

| Gauche5 (I) | C1 | -231.68961573 | 1.91 | |||

| Gauche6 (G) | C1 | -231.68916020 | 2.20 | |||

| Anti1 (B) | C2 | -231.69260237 | 0.04 | |||

| Anti2 (E) | Ci | -231.69253528 | 0.08 | |||

| Anti3 (K) | C2h | -231.68907066 | 2.25 | |||

| Anti4 (H) | C1 | -231.69097055 | 1.06 |

It can be seen that of the 10 different conformations, gauche3 (D/F) has the lowest energy. Furthermore, anti1 (B) has the lowest energy of the a.p.p series, which indicates that the inital guess conformers were quite accurate. The relative energies of the different conformers can be rationalised by looking at their structures. The Newman projections of all the 10 different conformers, including 2 enantiomeric conformations, are shown in Figure 3. Conformations A, B and C are generated from rotation about the central Csp3-Csp3 bond of 1,5-hexadiene with antiparallel vinyl groups. Rotation about the same central bond of 1,5-hexadiene with parallel vinyl groups gives conformations D, E and F. Conformations G, H and I are formed by rotating around the central bond while one of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds is in an s-cis orientation (CC eclipsing C=C). If both of the Csp3-Csp2 bonds are in the s-cis orientation, rotation around the central bond gives conformations J, K and L. Conformations D and F are enantiomeric pairs, and so are conformations J and L.

From Table 2, we can see that the ordering of the relative energies of the different conformations is as follows: D/F < B < E < A < C < H < I < G < K < J/L. The conformations that involve at least one s-cis Csp3-Csp2 bond (G-L) are all higher in energy than the other conformations. This was suggested to be caused by steric interactions between the vinyl protons, which are located close to each other.[5] Out of these, H is at the lowest energy due to only one s-cis Csp3-Csp2 interaction and an anti conformation. Conformations J/L have the highest energy due to two s-cis Csp3-Csp2 interactions and a gauche arrangement. Out of the lower-energy conformations A-F, the global minimum is gauche3 D (F), possibly due to an attractive interaction between the π orbital and the vinyl proton. Interestingly, while this energy ordering is consistent with the results reported in some literature examples,[6] there are also other examples[5] that report the anti1 conformer B to be the lowest energy conformation instead. By looking at the reported energy values in Table 2, the difference in energy between gauche3 D (F) and anti1 B is only 0.04 kcal/mol. This negligible energy difference is more than ten times smaller than the energy difference between the gauche and anti conformations of n-butane.[5] Possibly, the precision of the current methods used does not allow for an accurate assessment of such small energy differences, resulting in different results obtained by the two literature examples.

After an analysis of the 10 different conformers, further studies were conducted on the Ci anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene. The previous studies employed the use of the Hartree-Fock theory. While this has proven to be very useful in the study of organic mechanisms, the method neglects electron correlations, which may cause problems in the calculation of activation energies for example.[1] The density functional theory (DFT) method provides a viable improvement to the Hartree-Fock theory by taking into account electron correlation. Therefore, the DFT method of optimisation (DFT is not a method of optimization, it is a method for calculating electronic energy. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)) at a higher level of theory was investigated. The Ci anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene was optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G* level. The total energy was found to be -234.55970565 a.u, and the point group remained the same as Ci (It is significant that the point group is the same, but does it mean that the geometries are similar? In ethene if you increase the CC bond length by 10Å does the point group change? Would you say the structures are similar? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)). By comparison to the energy obtained using the HF/3-21G level of theory (-231.69253528), it can be seen that a lower energy is obtained at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory, with a difference of about 2.867 a.u. From this we can tell that the DFT method provides a possibly more accurate energy value (Why is it possibly a more accurate value? One cannot compare absolute energies computed at different levels of theory. Absolute energies are not measurable and we can't say one is more exact that other a priori? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)), though the geometries and point group of the optimised structures remained the same.

Another valuable technique commonly used in computational studies of organic mechanisms is a harmonic frequency analysis. While the optimisation methods have provided us with the structure and energy of a stationary point on the bare potential energy surface, a frequency calculation allows us to characterise this stationary point as either a minimum or a saddle point on the hypersurface. A minimum on the hypersurface only has positive frequencies, while a transition structure has exactly one imaginary frequency, proportional to the square root of the negative force constant for motion along the reaction coordinate.[1] Consequently, to confirm that the optimised structure is indeed a minimum point on the potential energy surface, we should expect to see only positive frequencies. Therefore, from the optimised B3LYP/6-31G* structure, a frequency calculation at the same level of theory was then run. Information about the vibrational frequencies modes were obtained and no imaginary frequencies were observed, proving that this is indeed a minimum point. The IR spectrum is shown in Figure 4. From the spectrum, we can see that all the expected peaks corresponding to the vibrational modes of this molecule are present. Alkane Csp3-H stretches as well as alkene Csp2=H can be observed in the 2850-3100 cm-1 region. The C=C stretching of the double bond can also be observed in the 1640-1680 cm-1 region. The typical fingerprint region is observed below 1300 cm-1.

Additional information regarding thermodynamic quantities can also be obtained from this calculation. These can be located in the Thermochemistry section of the output file. The energies of interest are estimates of the total energy of the molecule, after various corrections are applied. These include:

i) the sum of electronic and zero-point energies (E = Eelec + ZPE) - this represents the potential energy at 0K including the zero-point vibrational energy;

ii) the sum of electronic and thermal energies (E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot) - this represents the energy at 298.15K and 1 atm, and includes the translational, vibrational, and rotational contributions;

iii) the sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies (E = Eelec + H) - this contains a correction for RT (H = E + RT) (Under which conditions is this true? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)); and

iv) the sum of electronic and thermal free energies (E = Eelec + G) - this includes the entropic contribution (G = H - TS) (How could the value of the entropy be estimated? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)).

The frequency calculations of the optimised B3LYP/6-31G* anti2 structure was conducted at 298.15 K as well as 0 K and the results are summarised in Table 3 as follows:

| Energy | At 0 K | At 298.15 K |

|---|---|---|

| E = Eelec + ZPE | -234.416246 | -234.416255 |

| E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot | -234.416246 | -234.408962 |

| E = Eelec + H | -234.416246 | -234.408018 |

| E = Eelec + G | -234.416246 | -234.447873 |

From the results, we can see that the values for all the different energies at 0 K are the same. This is within expectation by considering some characteristic properties of the system at 0 K. Firstly, we can see that the translational, vibrational and rotational motions do not contribute to the energy of the molecule at 0 K. This makes sense because at absolute zero, all classical molecular motion ceases and the particles are at complete rest, retaining minimal, quantum mechanical motion. Furthermore, the correction for RT would be 0 in this case since T = 0. Lastly, the entropic contribution is also equal to 0, which is in accordance with the third law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of a system approaches zero as the temperature approaches absolute zero. Hence, these results are sensible. Comparison of the energies at 0 K and 298.15 K also provides us with interesting information about the system. By comparing the sum of electronic and zero-point energies, we can see that the values are extremely similar, which is also within expectation as the zero-point energy is a characteristic energy of a system and we would not expect that to change with temperature. The zero-point energy is the lowest possible energy that the system should have; it is the energy of its ground state. This arises from fluctuations even in the ground state of the system, resulting in motions even at absolute zero. Next, by comparing the sum of electronic and thermal energies, the energy is higher at 298.15 K than at 0 K, which is once again reasonable as the translational, vibrational and rotational motions start to contribute at higher temperatures. The sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies is also higher at 298.15 K than at 0 K, which makes sense because thermal energy RT makes a larger contribution at higher temperatures. The last result, however, is interesting as the sum of electronic and thermal free energies is lower at 298.15 K than at 0 K. Intuitively, we would expect that this energy should be higher at 298.15 K due to a larger entropy in the system at higher temperature. This counter-intuitive result cannot be easily explained and may possibly be attributed to experimental errors (Do you think you typed the value correctly? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)).

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

Having done an intensive analysis on the structure and properties of 1,5-hexadiene (the reactant and product), it is now of interest to do an optimisation of the transition structures instead. As previously mentioned, the Cope rearrangement has now been widely accepted to be a concerted reaction, involving a single aromatic-type transition structure such as the 'chair' and 'boat' structures. Both of these structures consist of two C3H5 allyl fragments. Hence, the first step to this exercise was to optimise the allyl fragment. This was done at the HF/3-21G level of theory and an energy of -115.82304010 a.u. was obtained, with a C2v point group.

The next step was to optimise the 'chair' transition structure. The term 'transition structure' has been used to describe a first-order saddle point on the computed potential energy surface. The first order saddle points are stationary points just like minima; however, the difference is that one of the second derivatives in the first order saddle is negative. This means that the search for the transition state attempts to locate stationary points with one negative second derivative. One reason why transition state optimisation is more difficult than minimisation is that the calculation needs to know where the negative direction of curvature (i.e. the reaction coordinate) is. To solve this problem, a successful search should start off in a region where the reaction coordinate already has a negative curvature - that is, in a region fairly close to the quadratic region of the transition state.[7] This can be done by manually building a guess structure and then optimising it to a transition state. This is one of the most commonly used techniques for the location of a transition structure and is often successful for simple reactions for which chemical intuition provides reasonable transition state guesses. However, one of the downsides of this method is the high computational cost as the force constant (Hessian) is calculated once and then updated during the search. If the guess structure is far from the actual transition structure, this method may not work too well. An alternative is to freeze the reaction coordinate and then minimise the rest of the molecule. Once the molecule is fully relaxed, the reaction coordinate can then be unfrozen and the transition state optimisation can be started again. The advantage of this is that it may not be necessary to compute the whole Hessian, resulting in lower computational cost.

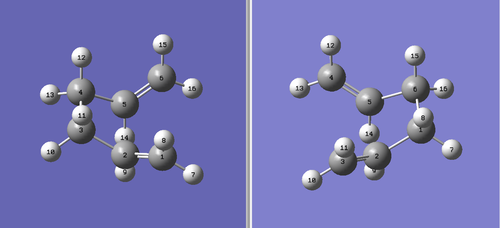

These two transition structure optimisation methods were explored with the 'chair' transition structure. A guess structure was built using two of the previously optimised allyl fragment. The distance between the terminal ends of the allyl fragments were set at approximately 2.2 Å (specifically 2.19 and 2.22 Å). The transition state optimisation (Berny) was then run at the HF/3-21G level of theory. The resulting optimised structure indeed corresponded to the 'chair' transition structure, with an energy of -231.61932246 a.u., C2h point group, and terminal C-C distance of 2.02 Å. Analysis of the vibrational frequencies also showed the presence of an imaginary frequency at -818 cm-1. This is important as it shows that we have indeed located a saddle point on the potential energy surface. The vibration is shown in Figure 5. This is very likely to be the one corresponding to the Cope rearrangement as we can see that the terminal ends of the allyl fragments approach each other during the vibration. The successful location of the 'chair' transition structure using this method shows that the initial guess structure was accurate enough.

Next, the frozen coordinate method was used. The terminal carbons from the respective two ends of the allyl fragments which form/break a bond during the rearrangement were frozen and then re-optimised to a transition state. This again successfully yielded the 'chair' transition structure, with an energy of -231.61932228 a.u., C2h point group, and terminal C-C distance of 2.02 Å. Again, an imaginary frequency is present at -818 cm-1. By comparison of the results obtained from the two different methods, we can see that there is practically no difference between the two structures obtained and it can be concluded that the 'chair' transition structure can be accurately determined using both of these methods.

Another common method for transition structure optimisation is the synchronous transit-guided quasi-Newton method, which uses a linear synchronous transit (LST) or quadratic synchronous transit (QST) approach to generate an initial guess and then optimise it to the transition state. In this case we are interested in the QST approach which means that the interpolation is carried out along the parabola that connects reactants and products. Typically, the initial guess will be a structure exactly halfway between the reactants and the products. There are two variations of the QST approach - QST2 and QST3. QST2 requires two molecule specifications as its input: the reactant and the product, while QST3 requires three molecule specifications: the reactant, the product, and an initial guess structure for the transition state. It is important to note that the numbering order of the atoms must be identical in the molecular specifications of all the two or three input structures.

This approach was explored with the 'boat' transition structure. From the optimised Ci anti2 structure, which is both the reactant and product in this case, the numbering was modified such that the reactant and product correspond to each other. The input diagram is shown in Figure 6. The QST2 calculation was then set up and the resulting transition structure located is shown in Figure 7. Upon inspection of this structure, it can be seen that this does not correspond to the 'boat' transition structure that we are trying to locate; in fact, this is the 'chair' transition structure that we have already previously located. The structure had an energy of -231.61932248 a.u., C2h point group, terminal C-C distance of 2.02 Å, and an imaginary frequency at -818 cm-1 - in near perfect agreement with what we have previously obtained for the 'chair' transition structure. The failure of the QST2 calculation to product the 'boat' transition structure is caused by the reactant and product geometries being more similar to the 'chair' transition structure instead. The possibility of a rotation around the central bonds was not taken into account by the program.

To solve this problem, we have to modify the reactant and product geometries so that they resemble closer to the 'boat' transition structure. This was done by changing the central C-C-C-C dihedral angle to 0°, and the inside C-C-C angle to 100°, for both the reactant and the product molecule. The input diagram is shown in Figure 8. The QST2 calculation was then set up again and as expected, the resulting transition structure located corresponds more closely to the 'boat' transition structure. An energy of -231.60280200 a.u. was obtained, with the C2v point group, and terminal C-C distance of 2.14 Å. An imaginary frequency is present at -840 cm-1, showing once again that we have successfully located a saddle point on the potential energy surface. The vibration is shown in Figure 9.

This shows that while the QST2 may possibly lead to the location of the transition structure, it may not be accurate enough if the reactant and product geometries are not close to the transition structure. Consequently, QST3 may be a more reliable method, as it allows the input of a guess transition structure. This was thus further explored with the 'boat' transition structure. The guess structure was built up once again using the previously optimised allyl fragment, and the distance between the terminal ends were set at approximately 2.2 Å (specifically 2.20 and 2.23 Å). The input diagram is shown in Figure 10. (What is the merit of doing a QST3 calculation in this case? You already obtained the transition state from these "reactant" and "product" structures with the simpler QST2 method. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST))

The QST3 calculation was then set up and the 'boat' transition structure was successfully located within one attempt. An energy of -231.60280245 a.u. was obtained, with the C2v point group, terminal C-C distance of 2.14 Å, and once again an imaginary frequency at -840 cm-1. The results are practically the same as that obtained using the QST2 method; however, this is much more reliable owing to an additional input of the guess transition structure. It can thus be concluded that the 'boat' transition structure had been successfully located using the QST2 and QST3 methods.

Having optimised the reactant and product structures as well as the transition state structures, the next step in the analysis is to run an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation. This calculation will connect the transition state structure to those of the products and the reactants, by following the minimum energy path from a transition structure down to its local minimum on a potential energy surface. This will give us information on the conformer that the transitions structures will lead to. Therefore, the IRC calculation was performed on the optimised 'chair' transition structure. The computation was done only in the forward direction as the reaction coordinate is symmetrical (since both reactant and product molecules are the same), and 50 points along the IRC were specified. The force constants were computed at every step. Upon completion of the job, 44 different geometries were observed and the potential energy diagram is shown in Figure 11.

Upon examination of the last point on the IRC (geometry no. 44), this structure has an energy of -231.69157851 a.u. and C2 point group. This is not in correspondence with any of the 10 conformers of 1,5-hexadiene that we have previously located. This suggests that the minimum geometry has not been located yet. Consequently, it was attempted to do a normal minimisation of this last point on the IRC. The resulting structure had an energy of -231.69166702 a.u., with C2 point group. This corresponds to the gauche2 structure as previously identified. This proves that the structure previously located directly from the IRC was not a minima (The two structures are likely not very different. What may happen is that the minimization calculation may have stricter convergence criteria than the IRC calculation. You could define a stricter convergence criteria for the IRC calculation such that you obtain a better agreement. You can look up on the Gaussian manual how to do this. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)), and that normal minimisation did indeed lead to a minima. The structure obtained is shown in Figure 12.

However, this approach may not necessarily give us the correct minimum. A more reliable method would be to specify a larger number of points on the IRC, though this involves a higher computational cost (If your calculation converged after 44 steps, simply allowing for a higher number of steps would not change the result. You would need to increase the number of effective steps by increasing the convergence criteria as described above. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)). Furthermore, if too many points are needed, the wrong structure may also be produced. Nevertheless, this was attempted once again on the same 'chair' transition structure, specifying 200 steps instead of 50 this time round. The last point on the IRC gave a structure with an energy of -231.69157893 a.u. and C2 point group. This is almost identical to the structure obtained using 50 steps and does not correspond to any of the conformers, showing that 50 steps was already enough to locate a structure close to minimum, and that increasing the number of points did not bring about much additional advantage (Dito. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST)). To locate the minima, a normal minimisation of the last point on the IRC was once again conducted and the resulting structure had an energy of -231.69166702 a.u., with C2 point group. This is identical to that obtained previously, and corresponds to the gauche2 conformer. From these results, we can tell that the local minimum on the potential energy surface from the transition state is the gauche2 confomer. This suggests that there could potentially be another energy barrier to the global minimum, the gauche3 conformer.

Finally, the last step of the investigation required a calculation of the activation energies for the Cope rearrangement via both transition structures. To do this, we must re-optimise our transition structures at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. The reason for this is that Hartree-Fock calculations neglect electron correlations, and since the correlation energy is generally larger in transition states than in reactants, the resulting activation energies are often too large compared to experimental values.[1] Hence, the DFT method provides a more reliable alternative in this case. From the HF/3-21G optimised 'chair' transition structure, an optimisation and frequency calculation was carried out at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. The resulting structure had an energy of -234.55698501 a.u., C2h point group, terminal C-C distance of 2.02 Å, and a single-imaginary frequency at -562 cm-1. The geometry of the 'chair' transition state is identical to that obtained at HF/3-21G level of theory; however, the energy is much lower (c.f. -231.61932228 a.u. as previously obtained using RHF). The presence of an imaginary frequency proves once again that we have located a saddle point on the potential energy surface. This re-optimisation was similarly performed on the HF/3-21G optimised 'boat' transition structure. The resulting structure had an energy of -234.54309327 a.u., C2v point group, terminal C-C distance of 2.25 Å, and a single-imaginary frequency at -540 cm-1. Once again, the point group and C-C distance are extremely similar to that obtained at HF/3-21G level of theory; however, the energy is much lower (c.f. -231.60280245 a.u. as previously obtained using RHF).

Having re-optimised the transition structures at the higher level of theory, the thermodynamic data was once again extracted and summarised in Table 4 below. The frequency calculation was also conducted at 0 K at both levels of theory in order to have a meaningful comparison. These values can be converted to standard units for energies (1 hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol) and then the activation energies can be calculated in order to compare with experimental values. The results are summarised in Table 5.

Table 4. Summary of Energies (in Hartree)

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | E = Eelec + ZPE | E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot | Electronic energy | E = Eelec + ZPE | E = Eelec + Etrans + Evib + Erot | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619322 | -231.466704 | -231.461346 | -234.556985 | -234.414921 | -234.408998 |

| Boat TS | -231.602802 | -231.450928 | -231.445299 | -234.543093 | -234.402340 | -234.396008 |

| Anti2 | -231.692535 | -231.539540 | -231.532565 | -234.611710 | -234.469204 | -234.461855 |

Table 5. Summary of Activation Energies (in kcal/mol)

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | B3LYP/6-31G* | Expt. | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair) | 45.69 | 44.69 | 34.06 | 33.17 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat) | 55.60 | 54.76 | 41.95 | 41.32 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The results are in perfect agreement with the expected values. We can draw a few conclusions from this. Firstly, we can see that the energies obtained at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory are lower and closer to that of the experimental values. This result is within expectation because the RHF calculations, as previously discussed, often give an overestimate of the activation energies due to the neglecting of electron correlation. Secondly, we can also see that the energies obtained at the B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory at both 0 K and 298.15 K agree to a large extent with experimental values, showing that the computational methods invoked in this experiment are accurate in predicting the activation energies of a reaction. Lastly, by comparison of the activation energies of the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures, we can see all the activation energies for the 'chair' transition structure is lower than that for the 'boat' transition structure. The fact that the reaction pathway involving the 'chair' transition structure requires lower activation energy suggests that the preferred reaction pathway of the Cope rearrangement is the one that involves the 'chair' transition structure.

In conclusion, in this exercise we have explored various computational methods to first analyse the structure and relative energies of the 10 different conformers of 1,5-hexadiene, and then locate both the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures of the Cope rearrangement. It can be concluded that the reaction pathway involving the 'chair' transition structure involves lower activation energy hence is the preferred reaction pathway.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels Alder cycloaddition is undoubtedly one of the most famous pericyclic reactions known. This involves the addition of a diene to a dienophile, often resulting in a structure which contains a cyclohexene motif. The mechanism of this reaction has been widely debated over the past few decades. Two limiting mechanisms have been proposed: one involving a synchronous or asynchronous transition state in a concerted mechanism, and one involving a diradical intermediate in a stepwise (non-concerted) mechanism.[3] However, it is more widely accepted that the mechanism is a concerted one, as this agrees with Woodward-Hoffman's rules of orbital symmetry as well, though many have argued that it may not be perfectly synchronous; that is, the bond forming lengths are very different. (References? João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST))

In this section of the experiment we focus on the use of semi-empirical computational methods instead. These methods are based on the Hartree–Fock formalism, but are simplified through approximations for various intergrals. Many of the integrals are approximated by functions with empirical parameters. This is hence less computationally costly and are important for large molecules where the full Hartree-Fock method may be too expensive. In the AM1 (Austin Model 1) method, the approximation involves a neglect of differential diatomic overlap, by reducing the repulsion of atoms at close inter-atomic distances.[8]

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition of Cis-butadiene and Ethylene

We will start the investigation of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition by first exploring the reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene (Figure 13). Two π systems are involved, with the cis-butadiene contributing 4π electrons, and the ethylene contributing 2π electrons. The total electron count is thus 6 (4n+2, n=1). According to Woodward-Hoffman's rules for the conservation of orbital symmetry,[9] this reaction is expected to proceed with suprafacial components only under thermal conditions. We can thus classify this as a π4s + π2s cycloaddition.

To start off, we first need to analyse the reactants - cis-butadiene and ethylene. An optimisation of cis-butadiene was done using the semi-empirical AM1 method, and an energy of 0.04879719 a.u. and point group of C2v was obtained. Similarly, ethylene was optimised using the same method, giving an energy of 0.02619028 a.u. and point group of D2h.

Pericyclic reactions are governed by selection rules for the conservation of orbital symmetry - that is, the transformation of the molecular orbitals of reactants into those of products must proceed continuously by following a reaction path along which the symmetry of these orbitals remains unchanged.[9] It is thus of interest to examine the molecular orbitals (MOs) of cis-butadiene and ethylene. As reactions often involve the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), we will focus on these only. The HOMO and LUMO of cis-butadiene and ethylene are shown in Figures 14 and 15 respectively.

(b)

(b)

(b)

(b)

We are interested in the symmetry of these MOs. There are two independent symmetry operations which may be used to classify these orbitals: a mirror plane perpendicular to the plane of the molecule, and a C2 rotational axis passing through the central C-C bond. For the purposes of this exercise we are mainly interested in the mirror plane bisecting the molecule. We can tell from the molecular orbital diagrams that the HOMO of cis-butadiene is antisymmetric (a) with respect to the mirror plane, while the LUMO is symmetric (s). Also, the HOMO of ethylene is symmetric (s) with respect to the mirror plane, while the LUMO is antisymmetric (a).

Having optimised the reactant structures, the next step is to construct a transition structure for this reaction. By considering the MOs of the reactants, it seems that the most reasonable approach to maximise orbital overlap is a symmetric approach, with the mirror plane of symmetry bisecting the two components. This means that the two planar molecule approach parallel to each other in a maximum-symmetry approach. With this knowledge, a guess transition structure was constructed using the optimised reactant structures. The ethylene molecule and butadiene molecule were arranged parallel to each other, with the terminal reacting ends set at approximately 2.2 Å apart, as per the Cope rearrangement. Transition state optimisation was done using the frozen coordinates method at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. A transition structure was successfully located, with a total energy of 0.11165494 a.u., Cs point group, and the bond lengths of the partly formed σ C-C bonds is 2.12 Å. A single-imaginary frequency was observed at -956 cm-1, proving that this is indeed a saddle point on the potential energy surface. The transition structure is shown in Figure 16.

A few levels of analysis can be conducted from here. Firstly, the C-C bond length of 2.12 Å of the partly formed σ C-C bonds in the transition structure is an interesting result. By considering the typical sp3 C-C bond length of 1.54 Å and the sum of the Van der Waals radii for carbon 3.4 Å (1.7 Å + 1.7 Å), this value is somewhere in between which suggests that there is an attractive interaction between the two ends; however, a single covalent bond has not been completely formed yet. Furthermore, the typical sp2 C=C bond length is 1.34 Å, but the C=C bond length in the ethylene molecule in this transition structure has lengthened to 1.38 Å, suggesting that the bond is taking up some sp3 character en route to the product. The C-C bond lengths in the cis-butadiene in this transition structure are 1.38 Å, 1.40 Å and 1.38 Å (C1-C2, C2-C3, C3-C4 bonds respectively), which is different from that of the reactant molecule of 1.34 Å, 1.45 Å and 1.34 Å. This suggests that the double C=C bonds are slowly becoming more sp3-like, while the single C-C bond is taking up more double bond character. The change in geometry can also be observed through the bond angles. The ethylene H-C-H bond angle in the transition structure is 115°, distorted away from the sp2 bond angle of 120°. The dihedral angle of the terminal alkenyl groups of the cis-butadiene (H-C1-C2-H) also changes from 180° to 156°. All these intermediate bond lengths and modified bond angles are characteristic trademarks of transition states and are within expectation.

Next, leading on from the analysis of the MOs of the reactants, we can also look at the MOs of this transition structure. The HOMO and LUMO is shown in Figure 17. We can see that the HOMO is antisymmetric (a) with respect to the mirror plane, while the LUMO is symmetric (s). By comparing to the MOs of the reactants, we can see that the HOMO of the transition structure is formed from the asymmetric HOMO of cis-butadiene, and asymmetric LUMO of ethylene. Similarly, the LUMO of the transition structure is formed from the symmetric LUMO of cis-butadiene, and symmetric HOMO of ethylene. In this way, combination of the reactant MOs bearing the same symmetry has produced a transition structure bearing the same symmetry. Orbital symmetry is conserved, and this reaction is hence allowed. Taking this discussion a little further, we can see that the HOMO of the transition structure is formed by the overlap of the HOMO of the electron-rich diene (cis-butadiene) and the LUMO of the electron-deficient dieneophile (ethylene). This is an example of a ‘normal’ electron demand Diels–Alder reaction.

(b)

(b)

Lastly, the vibrational modes of this transition structure is also interesting. Shown in Figure 18 is the vibration corresponding to the imaginary frequency at -956 cm-1 and the lowest positive frequency at 147 cm-1. The vibration at -956 cm-1 is the one corresponding to the reaction path at the transition state. We can see that the ends of the reacting fragments approach each other at the same time, indicating that bond formation is synchronous. An asynchronous bond formation would be caused by a vibration similar to that at 147 cm-1, where one end of the reacting fragments approach each other faster than the opposite end does, resulting in the formation of one bond faster than the other. However, as this is not the vibration corresponding to the transition state, it is not indicative of the mechanism of the reaction.

(b)

(b)

In conclusion, we can tell that the Diels-Alder cycloaddition is governed by Woodward-Hoffman's rules of orbital symmetry. The transition structure is formed by a combination of the reactant MOs bearing the same symmetry. The conservation of orbital symmetry leads to an 'allowed' reaction.

Regioselectivity in the Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride

In the cycloaddition of more complex molecules with unsymmetrical dienophiles such as cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride, there presents an issue of regioselectivity. Two products can be formed, an endo product and an exo product, as shown in Figure 19. In the endo transition state, the substituent on the dienophile is oriented towards the diene π system, while in the exo it is oriented away from it. In such situations, the endo product is usually formed predominantly as a result of kinetic control. Woodward and Hoffman rationalised the endo-selectivity by considering secondary conformational effects, caused by symmetry-allowed mixing of unoccupied with occupied levels.[10] The orbitals on the atoms directly adjacent of the dienophile π system (henceforth referred as β and β' orbitals) can interact favourably with the orbitals of the diene π system, resulting in a lowering of energy.

To investigate this, we start first again by analysing the reactants. Cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride were both optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method. The optimised cyclohexadiene structure had an energy of 0.02771129 a.u. and a point group of C2. The optimised maleic anhydride structure had an energy of -0.12182418 a.u. and point group of C2v. The HOMO and LUMO of both cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride are shown in Figures 20 and 21.

(b)

(b)

(b)

(b)

From the MOs, we can see that there is indeed a possibility of secondary orbital overlap between the HOMO of cyclohexadiene and the LUMO of maleic anhydride (considering normal electron demand). In the case of an endo overlap, the β and β' orbitals of maleic anhydride can interact favourably with the diene π system. This interaction is illustrated in Figure 22, where there is additional stabilisation of the system by the secondary orbital interactions (yellow), in addition to the interaction between the atoms which are already forming a bond (green). However, if the orientation leads to an exo state instead, the β and β' orbitals are too far away to interact with the diene π system, hence there is no stabilisation from secondary orbital overlap.

(b)

(b)

To examine this, the transition structure for this reaction had to be located. Once again, a guess transition structure was constructed using the optimised reactant structures which were arranged parallel to each other. The terminal reacting ends were set at approximately 2.2 Å apart, as per the Cope rearrangement. Transition state optimisation was done using the frozen coordinates method at the semi-empirical AM1 level of theory. Both transition structures were successfully located. The endo transition state had an energy of -0.05150479 a.u., Cs point group, and the bond lengths of the partly formed σ C-C bonds is 2.16 Å. A single-imaginary frequency was observed at -806 cm-1, proving that this is indeed a saddle point on the potential energy surface. The exo transition state had an energy of -0.05041985 a.u., Cs point group, and terminal C-C bond lengths 2.17 Å, and a single-imaginary frequency at -812 cm-1. Converting the energies of the two transition structures into standard units (1 hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol), the endo transition structure has an energy of -32.3197 kcal/mol whilst the exo transition structure has an energy of -31.6389 kcal/mol. This means that the endo transition structure has a lower energy and is more stable by 0.6808 kcal/mol. This is in accordance to what we expect, since the presence of secondary orbital interactions in the endo transition structure leads to a larger stabilisation hence lower energy of the molecule. The two transition structures are shown in Figure 23. The vibrations corresponding to the imaginary frequencies are shown in Figure 24. Again, the ends of the reacting fragments approach each other simultaneously, showing that this is a synchronous bond formation.

(b)

(b)

(b)

(b)

From the structure of the two transition states, we can see that the bond lengths of the partly formed σ C-C bonds are almost the same in both cases. However, the C-C through space distances are rather different. The distance between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment of the maleic anhydride and the C atoms of the “opposite” -CH=CH- for the endo structure is 2.89 Å, whereas the distance to the “opposite” -CH2-CH2- for the exo structure is 2.95 Å. This suggests that there may be some attractive interactions between the two ends for the endo structure, and some repulsive interactions betweeen the two ends for the exo structure. The attractive interactions in the endo structure are related to the secondary orbital interactions as previously discussed. For the exo structure, there could perhaps be some steric repulsion, seeing as the hydrogen atoms on the sp3 carbon atom are in close proximity to the (large) oxygen atom. The formation of the transition state forces the two fragments to come together, and with these steric repulsions, the exo transition structure is likely to be more strained and thus at a higher energy.

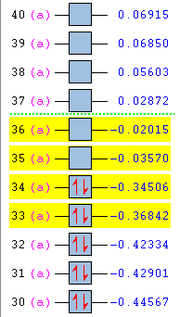

To determine if secondary orbital interactions are truly present, we need to look at the MOs of the endo transition structure. Comparing the orbital energies of the endo and exo transition structure, as shown in Figure 25, it can be seen that the HOMO-1, HOMO and LUMO+1 molecular orbitals (orbitals no. 33, 34, and 36 respectively) of the endo transition structure is at a lower energy than the corresponding ones in the exo structure. It is thus of interest to have a look at these MOs to see if there are any secondary interactions that can be observed.

(b)

(b)

Figure 26 shows the HOMO-1, HOMO, LUMO and LUMO+1 orbitals of the endo transition structure, while Figure 27 shows the corresponding orbitals of the exo transition structure.

(b)

(b)  (c)

(c)  (d)

(d)

(b)

(b)  (c)

(c)  (d)

(d)

Looking at the molecular orbitals, there does not seem to be any significant overlap between the β and β' orbitals of maleic anhydride with the diene π system in the HOMO-1, HOMO and LUMO of the endo transition structure. These results come as a slight surprise, as we have expected the presence of these interactions in the endo transition structure, and particularly more in the HOMO and LUMO which are the main orbitals involved in a reaction. Looking at the LUMO+1 however, it seems that there are indeed interactions present between the β and β' orbitals of maleic anhydride with the diene π system. Yet, these interactions seem to be also present in the exo transition structure. To have a better comparison of this LUMO+1 orbital in both of these structures, the orbitals need to be angled in a different way to better show the interactions. This is shown in Figure 28.

(b)

(b)

From Figure 28 we can see that the interactions in the endo TS are possibly greater than the corresponding interactions in the exo TS, since the overlap (red) area is bigger. This is to be expected as the β and β' orbitals of maleic anhydride are closer to the diene π system in the endo TS than in the exo TS (the distance is 2.89 Å in the endo TS v.s. about 3.76 Å in the exo TS). Yet, it is hard to neglect the presence of these interactions in the exo TS as well. It seems therefore, that the secondary orbital interactions may not be the major factor in the stabilisation of the endo TS. The concept of secondary orbital interactions have remained rather controversial, and while some evidence has been proposed to support this idea,[11] there also remains the argument of the insignificance of such interactions in certain systems. It has been proposed that secondary orbital interactions become significant only when the relative importance of steric interactions is minimal.[12] In the case of cyclopentadiene and maleic anyhydride (rather similar to the cyclohexadiene-maleic anhydride system under study here), it has been found that the cause of the endo preference is probably steric rather than electronic. We have also seen previously that there is some form of repulsion in the more strained exo TS. This is likely to be a possible reason for the disfavouring of the exo TS as well.

(Interesting discussion of the secondary orbital overlap effect. João (talk) 18:49, 13 April 2015 (BST))

In conclusion, it has been proved by computational studies that the endo transition structure is more stable than the exo transition structure and has a lower energy of 0.6808 kcal/mol. However, studies of the molecular orbitals do not directly give a clear indication of the additional presence of stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the endo TS, since such effects can be observed, though to a smaller extent, in the exo TS as well. Steric repulsions in the exo TS has been proposed to be a possible reason for the destabilisation of the exo TS; however, the relative importance of stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the endo TS against the destabilising steric repulsions in the exo TS remains a controversial topic that requires more in-depth computational studies.

Conclusion

In this experiment, the use of the Gaussview computational program to analyse the mechanisms of pericyclic reactions has been explored. Two main pericyclic reactions were studied - the Cope rearrangement and the Diels-Alder reaction. In the Cope rearrangement exercise, the reactant and product structures were optimised, and the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures were located using various techniques. A summary of energies at two levels of theory (HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G*) was obtained and the corresponding activation energies for the reaction pathways involving the 'chair' and 'boat' transition structures were calculated. The results were in close agreement with experimental results and it was concluded that the reaction pathway involving the 'chair' transition structure is the preferred reaction pathway. In the study of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, the semi-empirical AM1 method was used to neglect differential diatomic overlap, thus invoking lower computational cost. The study of the reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene was first done by optimising the reactants, and then locating the transition structure. It was found that the reaction was in close agreement with the rules of orbital symmetry. For reactions with unsymmetrical dienophiles such as maleic anhydride, there presents an issue of regioselectivity and it was found that the endo transition structure was more stable than the exo transition structure. However, the reasons for this preference are not clear and are likely to involve stabilising secondary orbital interactions in the endo TS as well as destabilising steric repulsions in the exo TS. Further more in-depth computational studies are required to study the relative importance of these two factors.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wiest, O., Montiel, D. C., Houk, K. N, J. Phys. Chem. A, 1997, 101, 8378–8388. DOI:10.1021/jp9717610

- ↑ Cope, A.C., Hardy, E.M., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1940, 62, 441–444. DOI:10.1021/ja01859a055

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Houk, K. N., Gonzalez, J., and Li, Y, Acc. Chem. Res., 1995, 28, 81–90. DOI:10.1021/ar00050a004

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:phys3; Date accessed = 18 Mar 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rocque, B. G., Gonzales, J. M., Schaefer, H. F., Mol. Phys., 2002, 100, 441–446. DOI:10.1080/00268970110081412

- ↑ Gung, B., Zhu, Z., Fouch, R., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117, 1783-1788. DOI:10.1021/ja00111a016

- ↑ Peng, C., Ayala, P. Y., Schlegel, H. B., and Frisch, M. J., J. Comp. Chem, 1996, 17, 49-56. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19960115)1

- ↑ Dewar, M. J. S., Zoebisch, E. G., Healy, E. F., and Stewart, J. J. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1985, 107, 3902–3909. DOI:10.1021/ja00299a024

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Woodward, R.B., Hoffman, R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 1969, 8, 781-932. DOI:10.1002/anie.196907811

- ↑ Woodward, R.B., Hoffman, R., J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87, 4388-4389. DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033

- ↑ Arrieta, A., Cossío, F. P., and Lecea, B., J. Org. Chem., 2001, 66, 6178–6180. DOI:10.1021/jo0158478

- ↑ Fox, M. A., Cardona, R., and Kiwiet, N. J., J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469–1474. DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016