Rep:Mod:CEW complab

Pericyclic Reactions

Pericyclic reactions have been an area of great interest and discussion since the 1930s [1]. Littmann proposed a stepwise mechanism with a coloured intermediate in 1935 [2], but now pericyclic reactions are accepted as being concerted and proceeding via a cyclic transition state. There are three main classes of pericyclic reactions: sigmatropic rearrangements, cycloadditions and electrocyclic reactions.

In this study the transition states were analysed for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene (a sigmatropic rearrangement) and the Diels-Alder reactions of ethylene/cis-butadiene and maleic anhydride/cyclohexa-1,3-diene (cycloadditions). The study considers the energies and structures of the transition states, the activation energies in the reaction pathways, and the effect of molecular orbitals on the structures.

Computational Methods

Three methods were used in this study to carry out the calculations: Hartree-Fock (HF), density functional theory (DFT) and semi-empirical/AM1. The HF approximation corresponds to molecular orbital theory and is often used as a starting point for carrying out calculations. It is an approximation that simplifies the Schroedinger equations for many-electron atoms and molecules, using the Born-Oppenheimer, independent electron and linear combination of atomic orbitals approximations [3] [4]. DFT is dependent on two theorems proved by Hohenberg and Kohn which state that the ground state energy from Schroedinger's equation is a functional of the electron density, which gives the true electron density when it is minimised [5]. B3LYP is most commonly used as the functional and is superior to other methods as it allows for the dissociation of molecules to be calculated, and gives accurate geometries which are consistent with experimental results [6]. The semi-empirical/AM1 method deals only with the valence electrons which allows for calculations to be carried out more easily, but this reduction in complexity leads to a lower accuracy being obtained in the results [7].

The basis sets used were 3-21G and 6-31G*. The 3-21G basis set is relatively simple, which splits each valence orbital into an inner and an outer shell. The inner shell is represented by two Gaussians and the outer shell by one, and each core orbital is represented by three. This basis set is useful for first row elements but leads to poor geometries for heavier elements. The 6-31G* basis set is less simplistic than the 3-21G as it incorporates polarisation functions. The valence orbitals are split into an inner part represented by three Gaussians and an outer part composed of one, and the core orbitals are given by six. The asterisk (*) represents the polarisation functions which are included for atoms that are heavier than helium. This basis set is more accurate for bigger molecules and has been widely used in the study of pericyclic reactions [8]

Nf710 (talk) 15:55, 1 December 2015 (UTC) This is an excellent understanding. you could have talked about how HF uses slater determinants, but your understanding of the various methods and the basis sets in excellent. Well done!

Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement which has been studied extensively to determine whether it goes by a boat or a chair transition structure [9].

Optimising the Reactants and Products

Firstly conformers with an anti and a gauche linkage were drawn and identified as the anti2 and gauche4 conformers. Their structures were optimised using the HF/3-21G method and basis set, and the gauche3 conformer was also studied to confirm that it was the lowest energy conformer. The structures, energies and point groups are summarised in the table:

| Conformer | Structure | Energy (a.u.) | Point Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| anti2 |  |

-231.69253528 | Ci |

| gauche3 |  |

-231.69266122 | C1 |

| gauche4 |  |

-231.69153032 | C2 |

The anti2 conformer was expected to be the lowest in energy due to the trans nature of the alkenes. However, computations led to the gauche3 conformer being found to have the lowest energy. This is due to orbital overlap between the π-systems being possible in the gauche3 HOMO, but not in the anti2 HOMO. The HOMOs are shown below:

Nf710 (talk) 15:59, 1 December 2015 (UTC) You have gone beyond the script here to show the orbital overlap from the .chk file, good work. nice comparison against the anti MOs

The anti2 conformer was re-optimised at the B3LYP/6-31G* level which gave an energy of -234.55970540 a.u.. The point group was unchanged and the geometry was not significantly altered by the higher level of theory. From this optimised structure a frequency calculation was run with the same level of theory which led to no imaginary frequencies. The thermochemical energies are recorded in the table below:

Nf710 (talk) 16:04, 1 December 2015 (UTC) you haven't given a very good comparison of the geometries, no dihedrals etc. furthermore you haven't stated your imaginary frequency

| Energy Type | Physical Significance | Energy (a.u.) |

|---|---|---|

| electronic + zero point energies | E = Eelec + ZPE | -234.416257 |

| electronic + thermal energies | E = E + Evib + E rot + Etrans | -234.408964 |

| electronic + thermal enthalpies | H = E + RT | -234.408020 |

| electronic + thermal free energies | G = H - TS | -234.447875 |

Optimising the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

An allyl fragment was drawn and optimised at the HF/3-21G level. This structure was used to build up the chair transition state by copying and pasting it into a new window. The distances between the terminal carbons of each fragment were set to 2.2 Å which was achieved by relaxing the symmetry. The chair transition state was first optimised to a TS(Berny) with the force constants calculated once in an Opt+Freq job, with the additional keywords Opt=NoEigen (chair1). Secondly it was optimised to a minimum using the frozen coordinate method, where the distances between the terminal carbons of each allyl fragment were set to 2.2 Å in the redundant coordinate editor (chair2). The bond forming and breaking distances were then further optimised (chair3). Each structure gave an imaginary frequency which corresponds to the chair transition state and this vibration for chair3 is shown.

Vibration for chair3 |

The imaginary frequency occurs due to the force constant, which is the second derivative of the potential surface, being negative at the energy maximum as there will be one negative eigenvalue. The negative force (k) constant leads to an imaginary frequency (ω) due to the dependence of the energy on the force constant given by:

Nf710 (talk) 16:08, 1 December 2015 (UTC) Good undertanding! well formatted

The table below summarises the results of the calculations carried out on the chair transition state, which were all at the HF/3-21G level.

| Structure | Energy (a.u.) | Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | (Sum of electronic and zero point energy) | (Sum of electronic and thermal energies) | C-C Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chair1 | -231.61932243 | -817.97 | -231.466700 | -231.461340 | 2.02046 |

| chair2 | -231.61518529 | -765.03 | -231.463806 | -231.458165 | 2.20000 |

| chair3 | -231.61932201 | -817.99 | -231.466690 | -231.461333 | 2.02056

2.01825 |

The boat transition state was then found by the QST2 method at the HF/3-21G level. This interpolates between a given reactant and product structure to find the transition state as the energy maximum between the two structures. The reactant and product have to be numbered in the same way in the atom list before any calculations can be run. Firstly the anti2 conformer was optimised using the TS (QST2) method but this led to an error as the reactant and product geometries were too far from the transition state geometry. The geometries were changed to give the reactant and product as shown below. The job was then rerun to give the boat transition state (boat1). The results of the calculation were summarised in the table below and the vibration corresponding to the imaginary frequency is shown.

Vibration for boat1 |

| Structure | Energy (a.u.) | <u.Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | (Sum of electronic and zero point energy) | (Sum of electronic and thermal energies) | C-C Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| boat1 | -231.60280212 | -839.83 | -231.450930 | -231.445299 | 2.14034

2.12055 |

In order to identify the conformers that are linked to the chair and boat transition states an intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) was run at the HF/3-21G level. The IRC was run in the forward direction only (as the reaction coordinate is symmetrical) and the force constant was calculated always. For the chair transition state the number of points was initially set to 50 but this did not reach a minimum (chair_irc1), so was then optimised to a minimum (chair_irc2). The IRC was then rerun with 80 and 100 points, which gave the same results (chair_irc3). For the boat transition state the number of points was initially set to 80, then to 100 which gave the same result (boat_irc1), then the structure was minimised (boat_irc2). The minimum energies reached for each job are summarised in the table and the reaction coordinates for chair_irc3 and boat_irc1 are shown below:

Nf710 (talk) 16:17, 1 December 2015 (UTC) You shouldn't have optimised them you should have let the IRC converge then compared the energies to the appendix to get the correct conf.

| Structure | Energy (a.u.) |

|---|---|

| chair_irc1 | -231.69157882 |

| chair_irc2 | -231.69166702 |

| chair_irc3 | -231.69157955 |

| boat_irc1 | -231.68298121 |

| boat_irc2 | -231.68302550 |

Finally, the activation energies were found for both the chair and boat transition structures. The transition structures and products from the chair_irc3 and boat_irc1 calculations were optimised in an Opt+Freq job type at the HF/3-21G and the B3LYP/6-31G* level, and the activation energies were found. The experimental activation energies at 0 K are 33.5 ± 0.5 kcalmol-1 for the chair transition state and 44.7 ± 2.0 kcalmol-1 for the boat transition state. The results obtained at the HF/3-21G level of theory are not within the experimental range, but those obtained at the B3LYP/6-31G* level are. This shows that using the higher level of theory can improve the computational results, but those carried out at the lower level of theory are useful as an initial result as they are not significantly different from the experimental results. The activation energies are summarised in the table below:

| Structure | Transition State Energy (a.u.) | Product Energy (a.u.) | Activation Energy at 298K (kcalmol-1) | Activation Energy at 0K (kcalmol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | ||||

| chair_irc3 | -231.61932201 | -231.69157956 | 44.16 | 45.32 |

| boat_irc1 | -231.60280212 | -231.68298121 | 49.24 | 50.31 |

| B3LYP/6-31G* | ||||

| chair_irc3 | -234.55698303 | -234.61070275 | 32.60 | 33.71 |

| boat_irc1 | -234.54307818 | -234.61132604 | 41.08 | 42.83 |

Nf710 (talk) 16:34, 1 December 2015 (UTC) It is clever how you have used the end of the IRC as your reactant/product. most people don't think to do that. At room temperature it is fine to just compare them from the same conformer as kT is larger than the energy gap. I will award you the marks here. its just a shame you didn't identify which conformers they connect. You have gone beyond the script here though in this respect as you have done an irc on both TS and used them to find the Ea.

Nf710 (talk) 16:34, 1 December 2015 (UTC) In general this is a good report its nice to see that you have understood the theory to an extent.

Diels-Alder Reactions

Diels-Alder reactions are [4+2]-cycloadditions which involve the reaction of a diene and a dienophile. They can show selectivity so the major product formed will be that which reacts via the lowest energy transition state.

cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

cis-Butadiene and ethylene were both built and optimised with the semi-empirical/AM1 method in an Opt+Freq job type. The energies were 0.04878534 a.u. and 0.02619027 a.u. respectively. The MOs for the anti-symmetric HOMO and symmetric LUMO (relative to the plane) of cis-butadiene are shown below.

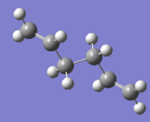

The transition state was found using a TS(QST2) job type with the semi-empirical/AM1 method and is shown below.

The length of the partly formed C-C σ bonds is 2.12 Å which is longer than the expected covalent bond length (cf. 1.54 Å and 1.34 Å for sp3 and sp2 carbon bonds respectively [10]) but is less than twice the Van der Waals radius of carbon (1.7 Å [11]) showing that there is a bonding interaction between the carbons in the transition state. The vibration which corresponds to the transition state occurs at -955.83 cm-1 and shows the bond formation of the two carbon-carbon bonds occurring synchronously. However, analysis of the lowest positive vibration at 147.11 cm-1 shows formation of one bond before the other.

(The lowest positive frequency is unrelated to bonding. Looking at the Jmol below, the carbons aren't moving in the direction of bonding - the arrows also show this Tam10 (talk) 16:33, 23 November 2015 (UTC))

Vibration for the transition state |

Vibration for the lowest positive frequency |

The anti-symmetric HOMO and symmetric LUMO for the transition state are shown below. The transition state HOMO is made up of the ethylene LUMO and the cis-butadiene HOMO, so the reaction is allowed as the interacting molecular orbitals have similar energies and good overlap.

(Include images of the HOMO and LUMO of ethylene to back up this statement Tam10 (talk) 16:33, 23 November 2015 (UTC))

(More specifically, they must have the same symmetry so the overlap integral is non-zero (including phase) Tam10 (talk) 16:33, 23 November 2015 (UTC))

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

The reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride can lead to an exo or endo product. The transition states for both the endo and exo product formation were found using the semi-empirical/AM1 method for a TS(QST2) job type. The properties of each isomer are summarised in the table below:

| Product | Product Energy (a.u.) | Transition State Energy (a.u.) | Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

-0.15990930 | -0.05041966 | -812.50 |

|

-0.16017034 | -0.05150472 | -806.31 |

The exo transition structure is higher in energy due to steric repulsions between the oxygen lone pairs and alkyl groups (-CH2), which aren't present in the endo transition structure. Furthermore, analysis along the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- fragment shows that there are more nodes along the axis in the endo structure's HOMO than in the exo HOMO, and considering the rest of the system the endo structure's HOMO has the ability for secondary orbital overlap between the carbonyl and the π-sytem of the diene, which isn't possible in the exo HOMO. Overall these factors lower the energy of the endo transition state so the endo product is thermodynamically favoured.

(With the reactant energies, you can calculate the activation and reaction energies. These energies can be converted to kJ/mol or kcal/mol so they're easy to understand Tam10 (talk) 16:33, 23 November 2015 (UTC))

References

- ↑ K. N. Houk, J. Gonzalez, Y. Li, "Pericyclic Reaction Transition States: Passions and Punctilios", "Acc. Chem. Res.", "1995", "28(2)", 81-90. DOI:[1]

- ↑ E.R. Littmann, "The Mechanism of the Diene Synthesis", "J. Am. Chem. Soc.", "1936", "58(7)", 1316-1317. DOI:[2]

- ↑ A. A Hasanein and M. W. Evans, "Computational Methods in Quantum Chemistry", "1996", World Scientific, Singapore.

- ↑ A. Szabo, N. S. Ostlund, "Modern Quantum Chemistry: An Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory", "1989", Dover Publications, Inc., New York.

- ↑ D. S. Sholl, J. A. Steckel, "Density Functional Theory: A Practical Introduction", "2011", John Wiley & Sons Inc., United States.

- ↑ I. Progogine, S. A. Rice, "Chemical Physics: New Methods in Computational Quantum Methods", "1996", John Wiley & Son Inc., Canada.

- ↑ T. Puzyn, J. Leszczynski, M. T. D. Cronin, "Recent Advances in QSAR Studies: Methods and Applications", "2010", Springer, United States. DOI:[3]

- ↑ E. G. Lewars, "Computational Methods: Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics","2nd edition", "2011", Springer, United States. DOI:[4]

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, K. N. Houk, "J. Am. Chem. Soc.", "1994", "116", 10336-10337 DOI:[5]

- ↑ A. A. Zavitsas, "The Relation between Bond Lengths and Dissociation Energies of Carbon-Carbon Bonds", "J. Phys. Chem.", "2003", "107", 897-898. DOI:[6]

- ↑ S. S. Batsano, "Van der Waals Radii of Elements", "2001", "37, 9", 1031-1046. DOI:[7]