Rep:Mod:BBcomp

This report describes the computational methods used to calculate transition state structures, reaction pathways and energy activation barriers characterised for the Cope Rearrangement and the Diels Alder Cycloaddition reaction. This was accomplished by numerically solving the Schrodinger equation using Molecular Orbitals-based methods through the Gaussian program.

Introduction

In this experiment, transition structures were examined in large molecules such as 1,5 hexadiene in the Cope rearrangement and cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride in the Diels-Alder cycloaddition. Apart from determining what transition structures look like, reaction paths and barrier heights were also calculated in order to determine the preferred reaction mechanism.

Pericyclics

Pericyclic reactions are most commonly known as concerted reactions that occur via a cyclic transition state. There are four types of pericyclic reactions that are recognised, namely: Cycloaddition, Electrocyclic, Sigmatropic, and Ene Reactions.

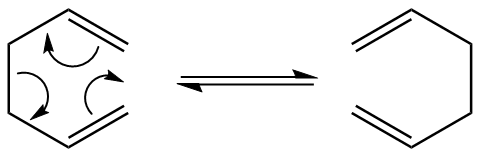

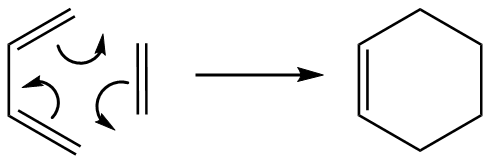

The Cope rearrangement is an example of a [3,3] Sigmatropic rearrangement. A sigmatropic rearrangement is a molecular rearrangement where a σ-bonded atom or group placed in between one or more π-electron systems, shifts to a new location. The prefix [3,3] indicates that there are 3 carbon atoms on either side of the broken sigma bond and the newly formed sigma bond. The mechanism of the rearrangement has been much debated over, the battle being between concerted, stepwise or dissociative. Now, it is agreed that the concerted reaction occurs via a 'chair' or a 'boat' transition structure. It is discussed later on the agreement of the B3LYP/6-31G theoretical transition state energies and the experimental data.

Computational calculations

The Gaussian program is a powerful tool that can be used to determine the structure and energies of a molecule. A range of methods can be used which depend upon two factors, namely: level of theory and basis set.

Three level of theories are addressed in this report, which are Hartree-Fock (HF) and Density Functional Theory (DFT), and Semi-Empirical. DFT is recognised as the most accurate out of the three, with respect to the energies and geometries calculated. This is because it takes into account spin and pairing energy. It also doesn't solve the Schrodinger equation using a single Slater determinant. Instead, it uses functionals (functions of another function) to determine properties of a many-electron system, which in this case is the spatially dependent electron density.

Nf710 (talk) 19:27, 21 January 2016 (UTC) You are correct in this case, but methods derived from HF (post HF methods) have been very developed and are better.

However, in larger basis sets, this tends to be much more computationally expensive, as the method attempts to get accurate energies of the electrons surrounding the molecule.

On the other hand, HF treats electronic repulsion as a function of a mean field which typically over estimates the term as it is a function of all the electrons when in reality it should be all of the electrons minus one which would then correspond to the respective repulsion on each electron. Since DFT uses the functional of electron density, this problem is not encountered.

Additionally, the basis set (also otherwise known as the mathematical description of the wavefunction) was also varied between the level of theories between the Pople basis sets: 3-21G & 6-31G.

The Cope rearrangement

Objectives:

- Locate the low-energy minima and transition structures on the C6H10 potential energy surface.

- Determine the preferred reaction mechanism.

It has long been the aim of several experimental and computational studies to determine the correct mechanism for the Cope rearrangement. This [3,3] sigmatropic shift has had its mechanism debated over for a long time, the battle being between it being concerted, step-wise, or dissociative. It is now generally accepted that the reaction occurs in a concerted fashion via either a "chair" or a "boat" transition structure, with the "boat" transition structure lying several kcal/mol higher in energy.[1] A high level of computational accuracy can be given by the B3LYP/6-31G level of theory has proved to give experimentally close activation energies and enthalpies. This tutorial below shows how the Gaussian is used to determine these values and to affirm that the transition states does indeed belong to that of a concerted mechanism. Due to the sp3 C-C centres, 1,5 hexadiene is open to adapting a wide range of anti and gauche conformations.

Optimising reactants & products

a) 1,5-hexadiene Anti-linkage

To calculate the minimum energy of the anti-conformer; 1,5-hexadiene was modeled (using the GaussView programme) with a dihedral angle of the central four carbon atoms set to 180° to mimic an anti-peri planar geometry. The structure was then 'cleaned' to standardise bond lengths and angles to more realistic values that simplify the computational calculations. A Hartree Fock optimisation was then carried out using the 3-21G basis set. See (Table 1) for results.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-231.69260235 a.u. | C2 |

|

Table 1. Gaussian calculation results for Anti(2) conformer

b) 1,5 hexadiene Gauche-linkage

This gauche conformation was modeled on GaussView with a dihedral angle between the central four carbon atoms set to 60°. The same level of theory was applied again and the conformer was optimised using the HF/3-21G method. One would expect the gauche linkage to have a lower energy than the anti structure above. However, this is not what has been observed, which may have been due to a steric clash between the terminal carbons.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-231.69166702 a.u. | C1 |

|

Table 2. Gaussian calculation results for Gauche(2) conformer

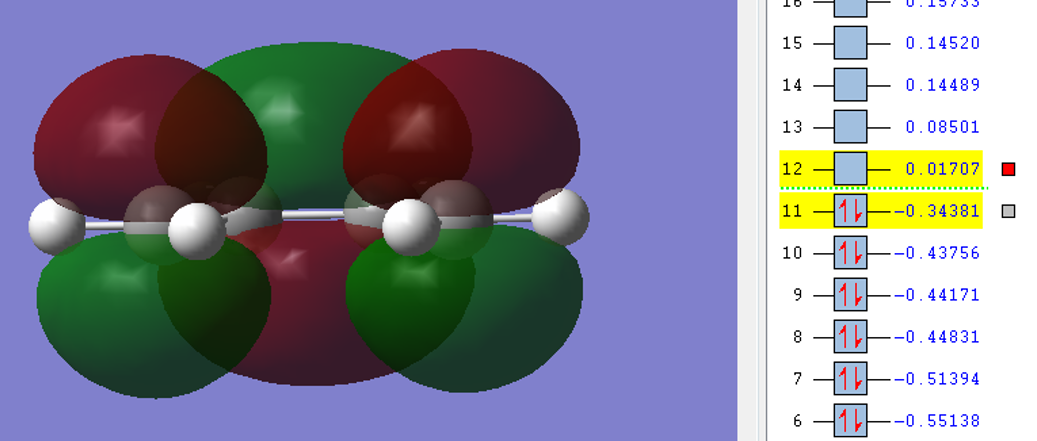

c) 1,5 hexadiene: Lowest energy conformation

Counter-intuitively, the Gauche(3) conformation possesses a lower energy level than that of the Anti(2) conformation. This is unexpected because the gauche conformer clearly experiences larger steric strain, which begs the question, what else might be contributing to the lowest energy conformation other than sterics? The answer can be found in the Molecular Orbitals of the Gauche conformation as shown in the figure below. This makes it clear that there is an additional favourable electronic bonding stabilising interaction in the gauche conformation between the terminal π orbitals of the molecule.

Nf710 (talk) 19:32, 21 January 2016 (UTC) very good use of the gauche orbitals to show why it is lower in energy

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-231.69266122 a.u. | C2 |

|

Table 3. Gaussian calculation results for Gauche(3) conformer

d) 1,5 hexadiene conformation with Ci symmetry

Since it was quite tricky getting the 1,5-hexadiene molecule to follow through an optimisation calculation with an anti geometry with a Ci symmetry, the point group was fixed at the beginning to ensure that the correct molecule would be generated through the calculation. This was done by adjusting the tightness of the point group symmetry prior to symmetrising the molecule.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-231.69253489 a.u. | Ci |

|

Table 4. Gaussian calculation results for Anti(2) conformer under HF

e) Reoptimisation of Ci symmetry 1,5 hexadiene conformation (DFT method)

The Anti(2) conformation above was reoptimised at the higher level theory B3LYP/6-31G under the DFT method. Apart from this, a frequency calculation was also run to confirm an energy minimum has been reached by ensuring all vibrational frequencies in the molecule are positive, real numbers.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-234.55970458 a.u. | Ci |

|

Table 5. Gaussian calculation results for Anti(2) conformer under DFT

The energy value obtained was a.u. which cannot be directly compared to that obtained from the HF/3-21G basis set as it is meaningless to compare energies from different basis sets.However, the geometries of the optimised structures can be compared successfully as shown in Table 6. below.

| anti 2-1,5-hexadiene | Bond length (Å) | Dihedral Angle | Point Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C6-C5 | C5-C4 | C4-C3 | C3-C2 | C2-C1 | C4-C1-C9-C12 | ||

| HF/3-21G | 1.31615 | 1.50886 | 1.55262 | 1.50886 | 1.31615 | -180.00000° | Ci |

| DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* | 1.33823 | 1.50720 | 1.55551 | 1.50720 | 1.33823 | -180.00000° | Ci |

Table 6. Comparison of geometries of Anti(2) conformer obtained from HF/3-21G basis set and DFT/B3LYP/6-31G basis set

It is obvious from the data in Table 6. that there are discrepancies in the lower level HF-optimised structure and the higher level DFT-optimised structure. The carbon-carbon bond lengths all seem to be ca. Å longer when using the DFT optimisation than the HF optimisation. The HF optimisation also exhibits a smaller angle of ° than that obtained at the higher level of theory DFT.

More importantly,since all the bond lengths vary equally between molecules, the point group remains unaffected, i.e. it is still Ci. This indicates that using either level of theory will give similar results so using more precise basis sets with a higher computational cost can be avoided.

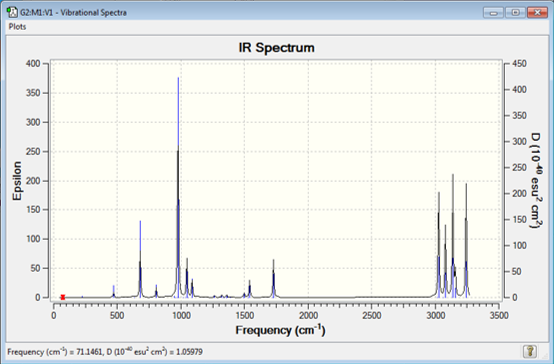

Frequency analysis

A frequency analysis was carried out on the molecule to ensure that the vibrations computed experimentally can be verified experimentally. The .chk file of the reoptimised anti2-1,5-hexadiene was used to set up a frequency calculation at the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G level of theory. No imaginary frequencies were observed, i.e. no negative numbers were seen. The IR peak at 900 cm-1 corresponds the Ch2 wag while the ones ranging from 3000-3200 cm-1 correspond to both sp2 and sp3 C-C stretches.

| Thermodynamic property | Energy/Hartrees |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | -234.469217 a.u. |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies | -234.461865 a.u. |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies | -234.460921 a.u. |

| Sum of electronic and thermal free energies | -234.500804 a.u. |

Table 7. Thermodynamic properties of Anti2-1,5-hexadiene

The sum of electronic and zero-point energies has been reported a temperature of 0K while the rest of the calculations have been performed at a temperature of 298.15K and at a pressure of 1 atm.

The zero-point energy of a quantum mechanical system is the lowest possible energy it may possess. 1,5-hexadiene has been modeled under the harmonic oscillator and therefore, its calculated zero-point energies may possess residual vibrational energies. The rest of the calculations were performed at 298.15K which introduces thermal energy, so the reported figures would have taken into account translational, vibrational, and rotational energy. The sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies includes an enthalpic correction for room temperature. Thermal enthalpy at constant pressure is given by the equation H=E+RT where H is enthalpy, E is energy, R is the gas constant, and T is temperature. At 0K, the RT term is 0 as well which means H=E. Whereas, if the temperature is higher than 0K, H≠E.

The sum of electronic and thermal free energies accounts for the entropic contribution of the free energy of the system. The equation to calculating entropic contributions to energy is given by the equation H=G+TS, at constant pressure. As temperature increases above 0K, enthalpy increases accordingly and the Gaussian uses this to determine a value for the entropy.

Optimising "Chair" and "Boat" Transition structures

This section investigates the 2 transition state structures possible: chair and boat.

To start off, an allyl fragment was drawn and optimised using the HF/3-21G basis set. A single optimised fragment was made to act as half the transition state molecules. Two of these fragments were brought close to each other with a distance of 2.2 Å between the two fragments, giving an intial 'guess' structure.

| Structure | HF/3-21G Energy | Point group | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

-115.82304011 a.u. | C 2v |

|

Table 8. Force constant computation of Chair Transition structure

Optimising a transition state is more difficult to successfully compute when compared to the previous optimisations described in this report. The main challenge here is to allow the transition state to converge to a saddle point - that corresponds to a transition state, which can be difficult due to the length iterative process.

3 methods have been investigated and described below, with the Force constant and Frozen coordinate method used for optimising the Chair Transition State and the QST2 method used for optimising the Boat Transition State.

Method 1: Computing Force constants

The 'guess' file was cleaned, symmetrised and saved as .gjf input file. An Opt+Freq calculation was then run at the HF/3-21G level and optimised to a TS(Berny) instead of a minimum which corresponds to a transition state, and not the lowest energy structure. The resulting molecule showed an imaginary (negative) frequency at -818.05 cm-1. The negative frequency obtained is indicative of a negative force constant that is present at the transition state. This point is a maximum on the potential energy surface and any displacement in either direction will move rapidly away from the Transition structure. In contrast, at a minimum, a positive force constant is seen that shows the stability of the structure, which is the inverse of what is seen at a transition state.

| Structure | Vibrations animation | HF/3-21G Energy | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair Transition State |

|

-231.61932235 a.u. |

|

Table 9. Force constant computation of Chair Transition structure

Method 2: Frozen coordinate method

This method involves freezing the bond lengths of the terminal carbon atoms using the redundant coordinate editor program in GaussView to 2.2 Å. Atoms that have not been frozen would continue their optimisation as normal under the Opt+freq optimisation under the HF/3-21G basis set. The output file obtained was then reoptimised to a TS(Berny) instead of a minimum. However, the C-C bond distances that were previously frozen were now allowed to optimise under a normal guess Hessian that took into account information about the two coordinates that the calculation is allowed to differentiate along.

| Structure | Vibrations animation | HF/3-21G Energy | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair Transition State |

|

-231.61932248 a.u. |

|

Table 10. Redundant coordinate computation of Chair Transition structure

Both methods give very similar vibrational frequencies and energies. It would also be useful to add that the bond breaking and bond forming lengths found using both methods are also quite similar with a difference of 0.00045 Å between the two. A summary of the differences can be found in Table 10 below.

| Method | Imaginary Vibration | HF/3-21G Energy | Bond-forming/-breaking length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force constant | Frequency: -818.05cm-1 | -231.69260235 a.u. | 2.02088 Å |

| Redundant coordinate | Frequency: -817.93cm-1 | -a.u. | 2.02043 Å |

Table 11. Comparison of Force constant computation and Redundant coordinate computational results

Method 3: QST2 Method

The QST2 method takes into account both the reagents and the product to run calculations to establish a suitable transition state, while the previous two methods modeled a pre-set molecule such that it would change into a transition state. In order to conduct this method, it was imperative that the reactants and products both were labelled correctly and consistently.

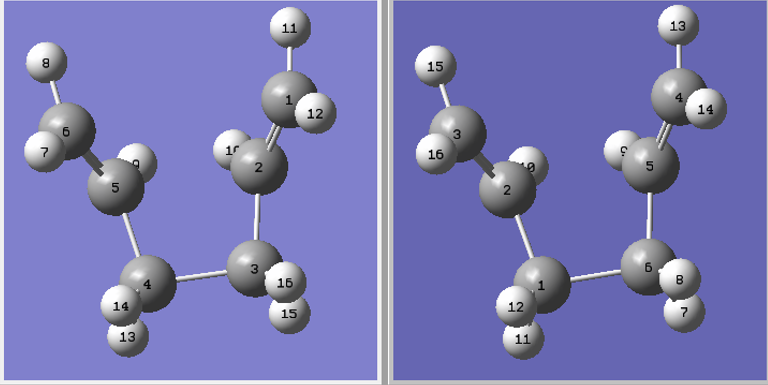

The calculation was run under the Opt+Freq and optimised to a TS(Berny) with the central C-C-C-C dihedral angle set to 0° and the angles of C2-C3-C4 and C3-C4-C5 were changed to 100° giving the following reactant and product molecules:

The calculation was set up to optimise the transition state to a TS(QST2) under the HF/3-21G basis set resulting in the following boat-conformer.

| Structure | Vibrations animation | HF/3-21G Energy | Results summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boat Transition State |

|

-231.60280219 a.u. |

|

Table 12. Redundant coordinate computation of Chair Transition structure

Nf710 (talk) 19:40, 21 January 2016 (UTC) your frequencies are correct

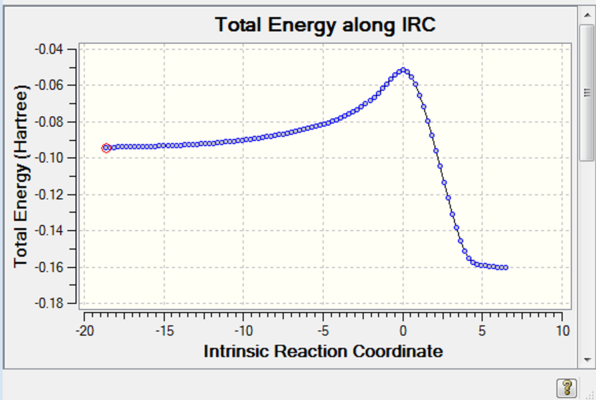

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC)

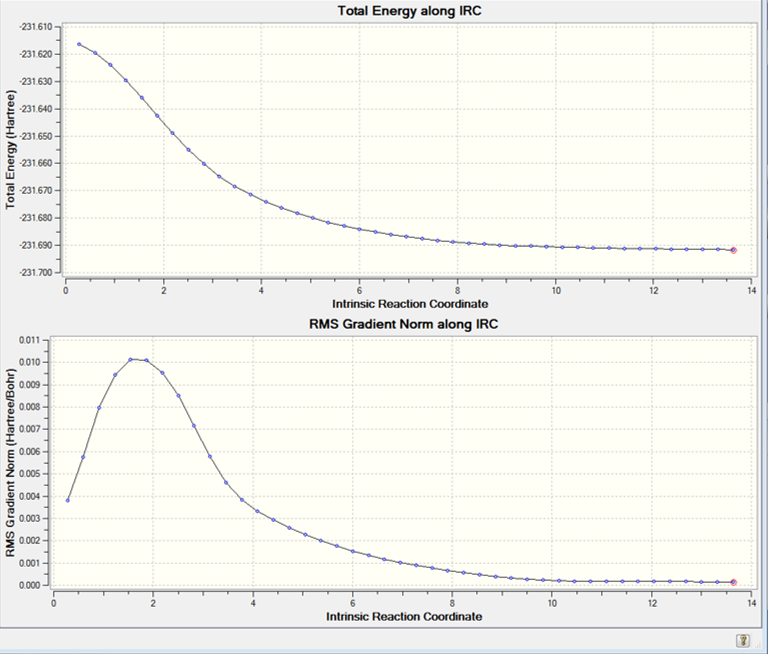

on was sufficient. The calculation was set to run 50 iterative steps at the HF/3-21G level using the transition state output file from the previous step. The resulting IRC pathways can be seen below.

The first graph shows the total energy along the IRC which describes how the total energy of the system had decreased along the reaction coordinate, while the second graph shows how the energy change along the reaction coordinate, i.e. a derivative of the first graph. The IRC stopped after using 44 iterative steps indicating that the product conformation had been reached.

Animation of Boat transition state turning to products |

In order to confirm that the product had indeed reached its local minimum and had the lowest energy structure possible, the product obtained from the 44th step was further optimised under the HF/3-21G level.

It was determined that the total energy of the structure of the 44th step is very close to that of its optimised structure indicating that the IRC could indeed optimise very well to the correct geometry.

Nf710 (talk) 19:41, 21 January 2016 (UTC) You should have optimised down the last structure

Activation energies

The following tables demonstrate the differences in the geometries of the transition state structures optimised at HF/3-21G and DFT/B3LYP levls of theory.

| Comparison of transition state geometries | Level of Theory | C-C (Å) Terminal bonds in chair conformer | C-C (Å) Central bonds in chair conformer | C-C (Å) Terminal bonds in boat conformer | C-C (Å) Central bonds in boat conformer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/3-21G | 2.02043 | 1.38927 | 2.13954 | 1.38140 | |

| DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* | 2.03724 | 1.40678 | 2.25430 | 1.39499 |

The differences between the geometries is minute when using the two different levels of theory but the differences are slightly more marked when examining the energy levels. This shows that even though the structure is optimised fairly accurately even at the lower levels, it is recommended to use the higher level of theory to calculate required energies.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |||

| Chair TS | -231.619532 | -231.466654 | -231.461548 | -234.556960 | -234.414654 | -234.408987 |

| Boat TS | -231.602984 | -231.450218 | -231.445987 | -234.543324 | -234.402387 | -234.395965 |

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.692535 | -231.539539 | -231.532565 | -234.611710 | -234.469874 | -234.461390 |

By looking at the energy differences between the reagent, the anti2-1,5-hexadiene molecule, and the transition states - chair and boat - the activation energies of each pathway can be easily established. These are shown in the table below.

| HF/3-21G | DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* | Eperimental | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298.150 K | 0 K | 298.150 K | 0 K | |

| Chair TS Activation Energy (kcal/mol) | 45.7098 | 44.6937 | 34.0805 | 33.1987 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat TS Activation Energy (kcal/mol) | 55.6036 | 54.7596 | 41.9785 | 41.3459 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The activation energies shown corroborate that the DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory reaches quite close to the experimentally obtained values. Moreover, at both at 0 K and 298.15 K, the activation energies are larger for the boat transition state. This implies that the chair TS is the favoured transition state pathway. As a side note, the activation energies are greater at 0 K due to the lack of thermal energy.

Nf710 (talk) 19:46, 21 January 2016 (UTC) Your energies are correct, you have done most of the stuff that you have been asked to do. and you have shown a goos understanding of the methods

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

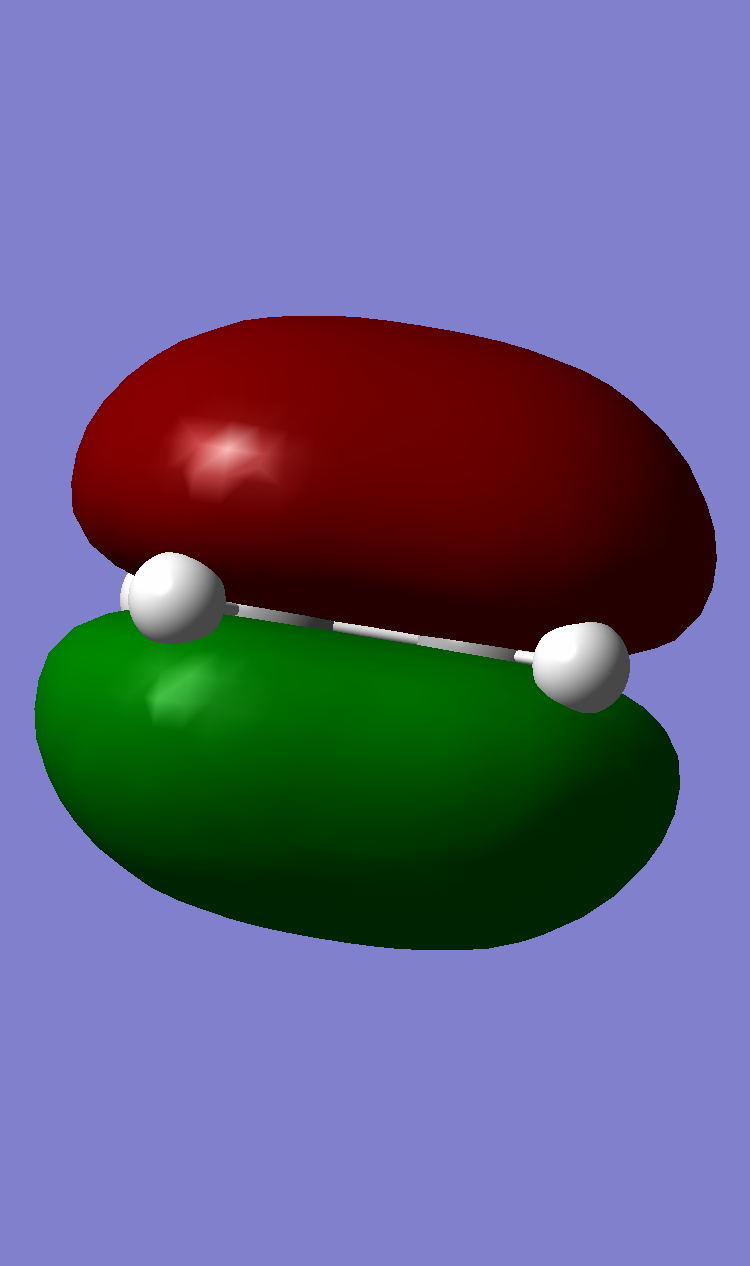

Cycloaddition of ethene to cis-1,3-butadiene

GaussView was used to model cis-butadiene with a set dihedral angle of 0° and a point group of C2v.

| Molecule | Structure | HOMO | LUMO | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cis-Butadiene |  |

|

| |||

| Ethene |  |

|

|

Table 13. Optimisation of reactants of Diels-Alder Cycloaddition

The HOMO of butadiene was antisymmetric with respect to the plane while the LUMO was symmetric. The converse was true for ethene.

Since the HOMO of butadiene lies higher than the HOMO of ethene, this reaction can be classified as one of normal electron demand. Upon further inspection, it can be seen that the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the dienophile come together rto give the TS symmetric LUMO. Similarly, the LUMO of the diene and the HOMO of the dienophile come together to form the TS antisymmetric HOMO.

Transition State Geometry

The two reactants were brought together with an envelope-type structure that maximised the overlap between the relevant orbitals. The point group was set to Cs with a distance between the bond-forming carbons of 2.1 Å. The structure was then optimised to at transition state using the optimisation to TS(Berny) under the Semi-Empirical AM1 level of theory. The results are tabulated below. One imaginary frequency was obtained at -956.26cm-1.

| Molecule | Structure | HOMO | LUMO | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State for

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition |

|

|

|

Table 14. Gaussian calculation results for Transition State optimisation of DA reactants.

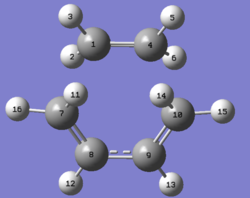

| Bond | Length/Å | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| C1-C4 | 1.38214 |

|

| C4-C10 | 2.11918 | |

| C10-C9 | 1.38185 | |

| C9-C8 | 1.39748 | |

| C8-C7 | 1.38186 | |

| C7-C1 | 2.11929 |

Table 15. Transition State Geometries

Typical bond lengths for sp3 and sp2 C-C bonds are 1.54 and 1.33 respectively. It is clear that most of the C-C bonds in the transition state structure lie between a single and double bond. C7-C9 is obviously longer than the rest of the bonds. This can be traced back to Hammond's Postulate which mentions that the transition state structure lies closest in geometry to the structure that has the highest energy and the least stability, in this case, the reactants. This is confirmed in the IRC below which shows that the reagents are less stable. It can also be inferred that the formation of the two new bonds is synchronous, which implies that they occur at the same time and the mechanism is therefore concerted.

(C7-C9? Tam10 (talk) 12:50, 15 January 2016 (UTC))

Fig: IRC graph

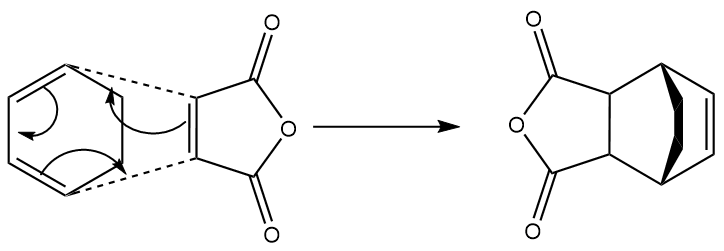

Regioselectivity of Diels-Alder Cycloaddition using Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

The second Diels-Alder reaction considered is one between cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. Maleic anhydride is electron poor due to the carbonyl substituents on the furan ring whereas the diene is electron rich due to the positive inducting effects of the attached R groups that donate electron density into the pi bond. As a rule of thumb, under kinetic conditions, the endo product is favoured over the exo product in a Diels-Alder reaction.

To begin with, both reactants were modeled using GaussView and optimised to a low energy structure. Both reactants were then brought together to form an initial 'guess' structure for the transition state.

Exo Transition state

For the exo transition state, both fragments were placed 2Å apart with the C=C bonds in hexadiene directly on top of the C=O bonds in maleic anhydride, and a point group of Cs. The structure was then optimised to a TS(Berny) under the Semi-Empirical A1 method. An imaginary frequency was obtained of -812.19cm-1.

| Molecule | Structure | HOMO | LUMO | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo Transition State for

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition |

|

|

|

Table 16. Gaussian calculation for Transition state optimisation of exo DA reaction

|

|

(This is actually the endo TS. Tam10 (talk) 12:50, 15 January 2016 (UTC))

Endo Transition state

For the endo transition state, both fragments were placed 2Å apart with the C=C bonds in hexadiene directly on top of the C=O bonds in maleic anhydride, and a point group of Cs. The structure was then optimised to a TS(Berny) under the Semi-Empirical A1 method. An imaginary frequency was obtained of -806.39cm-1.

| Molecule | Structure | HOMO | LUMO | Results summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo Transition State for

Diels-Alder Cycloaddition |

|

|

|

Table 17. Gaussian calculation for Transition state optimisation of exo DA reaction

|

|

Table 18. Comparison of Transition state geometries of exo and endo DA reaction

(This section cannot be marked Tam10 (talk) 12:50, 15 January 2016 (UTC))

Exo: C1-C4, C2-C3, C3-C4 and C9-C11 all have bond lengths that are in between that of a sp3 (1.54Å) and sp2 (1.33Å) hybridised carbon. These are the bonds that are either breaking/forming a new bond in a synchronous manner. It should also be noted that C1-C11 and C9-C2 have separations smaller than the overall sum of two VDW radii indicating that there is some form of electronic interaction.

IRC was also run that showed

Endo: C1-C4, C2-C3, C3-C4 and C9-C11 all have bond lengths that are in between that of a sp3 (1.54Å) and sp2 (1.33Å) hybridised carbon. These are the bonds that are either breaking/forming a new bond in a synchronous manner. It should also be noted that C1-C11 and C9-C2 have separations smaller than the overall sum of two VDW radii indicating that there is some form of electronic interaction.

IRC was also run that showed

Activation energies

(This section doesn't correspond with what you have above Tam10 (talk) 12:50, 15 January 2016 (UTC))

| Semi-Empirical AM1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies | Sum of electronic and thermal energies | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | ||

| Cyclohexa-1,3-diene | 0.027711 | 0.152503 | 0.157756 |

| Maleic Anhydride | -0.121823 | -0.063346 | -0.058192 |

| Endo TS | -0.051505 | 0.133493 | 0.143683 |

| Exo TS | -0.050390 | 0.134583 | 0.144871 |

| Endo Product | -0.160191 | 0.031369 | 0.040458 |

| Exo Product | -0.159989 | 0.031711 | 0.040671 |

The sum of the energies displayed in the table above can be converted to a more comparable unit using the conversion 1 Hartree = 627.509 kcal/mol. They are listed as follows:

| Activation Energy at 0 K / kcal/mol | Activation Energy at 298.15 K / kcal/mol | Reaction Energy at 0 K / kcal/mol | Reaction Energy at 298.15 K / kcal/mol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endo | 27.52 | 27.60 | -36.39 | -37.16 |

| Exo | 27.95 | 28.03 | -36.08 | -36.99 |

At both temperatures, it can be seen that the endo reaction pathway has a lower activation energy barrier when compared with the exo pathway. Thus, under kinetic conditions of the Diels Alder reaction, the major product is the the endo conformer. This is due to secondary orbital overlap between the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)-and the -CH-CH- pi systems. However, it can be seen that in the HOMO of the endo TS structure, the -CH-CH- π orbitals are out of phase with the -(C=O)-O-(C=O)- π orbitals. Moreover a nodal plane exists between them that confirms the unfavourable interaction. Therefore, based on the calculations carried out at the semi-empirical level of theory, a secondary orbital interaction is unlikely to cause the expected stabilising effect.

Conclusion

This report investigated example reactions of simple pericyclic reactions such as the Cope rearrangment and the Diels Alder Cycloaddition. First, investigations into the reaction pathways of the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene through 2 transition states : boat and chair, were carried out. Both the transition state structures were modeled at 2 levels of theory, namely: HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G. The geometries yielded by both methods were suitably accurate. It was determined that the chair transition state structure provided the lowest energy pathway with the smallest activation energy barriers at both 0 K and 298.15 K.

Secondly, the Diels Alder reaction between ethene and 1,3-butadiene was investigated. Initially, the reagents were optimised and then their ideal transition state structures were determined. The reaction proceeded as per predictions through frontier molecular orbital theory/using the Woodward-Hoffmann rules.

The Diels Alder cycloaddition between maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene was also examined to consider the effect of substituents and secondary orbital interactions for the wholeness of the report. The TS optimisation found the endo transition state structure to provide the lower energy, kinetically available reaction pathway. Through analysis of the molecular orbitals, it was seen that there was no evidence of a secondary orbital interaction, and that there was a instead a steric penalty of the CH2 groups in the exo product. In the future, the reaction could be investigated at a higher level of theory to more accurately develop the molecular orbitals of the transition state structures.