Rep:Mod:Az999HD

Synthesis and computational lab: 1C

Computational chemistry has become a powerful tool in the investigation of chemical reactions and serves as complementary to the traditional experimental chemistry. Indeed, some experimental reactions are not possible due to a variety of reasons and computational methods may be the only way in which modern chemists can obtain useful information from. This computational experiment is broken down into two parts. The first part examines some of the stability aspects of different conformers of Diels-Alder cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene and the hydrogenation of its dimer. In addition, Taxol derivatives were the subject of an extensive study on its atropisomerism, which also includes a NMR computation study.

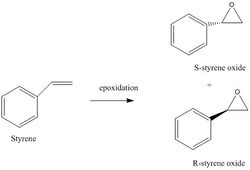

The second part of this computational experiment complements the counterpart of the 1C experiment, the synthesis 1S experiment. Where, the asymmetric epoxidation catalyst, including the Shi and Jacobsen catalyst were investigated. Two alkenes, styrene and R,R-trans-stilbene, were selected for an comprehensive study which explores its computed NMR spectrum, its optical rotation, its Vibrational Circular Dichroism computations, enantiomeric excess calculations and the transition states involving the catalysts as well as possible secondary interactions that may be involved in stabilising the reaction.

Conformational analysis using Molecular Mechanics

In the first part of this computational study, the programme Avogadro and Gaussview will be utilised to analyse the first perform conformational studies of the dimerisation and partial hydrolysis of cyclopentadiene.

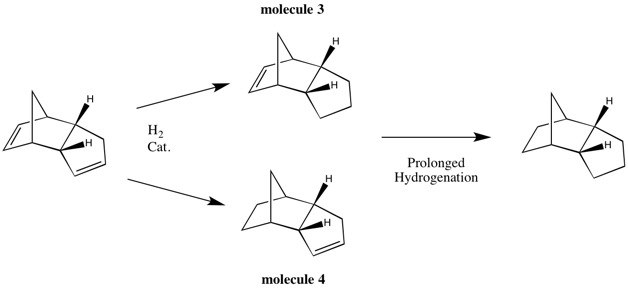

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Cyclopentadiene exists as dimers at room temperature due to its tendency to dimerise via the [π4s+π2s] Diels-Alder reaction [1]. As such, cyclopentadiene dimers can exist in two forms: the exo (molecule 1) and endo (molecule 2) form. It has been shown by experiment that the Diels-Alder reaction favours the endo product as the reaction proceeds under kinetic control.[2] Woodward and Hoffman has suggested that this preference is due to the 'Secondary Orbital Effects' where one of the C=C double bonds offers п orbital interactions, thus stabilising the transition structure of the endo form and lowering the activation energy for the particular pathway.

Two possible dihydro derivatives (molecular 3 & 4) can result from the hydrogenation of the dimers. Similar to the cyclodimerisation of the cyclopentadienes, the partial hydrogenation reaction can be shown to be either kinetically controlled or thermodynamically controlled based on computational studies.

In this section, the software Avogadro was used to construct the particular endo and exo forms of the cyclopentdiene dimer product as well as product from the partial hydrogenation reaction of the dimers. Their geometries were optimised using the MMFF9(s) force field option. The particular molecular structures as well as the absolute energy and the contribution from the stretching (str), bending (bnd),torsion (tor), van der Waals (vdw) and electrostatic energy are listed below (3D jmol models can be views by clicking the specific compund names).

| Compound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total bonding stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 3.54309 | 3.46794 | 3.31165 | 2.82317 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 30.77278 | 33.18933 | 31.93443 | 24.68480 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | -2.73094 | -2.94953 | -1.46930 | -0.37857 |

| Total van der Walls energy (kcal/mol) | 12.80148 | 12.35872 | 13.63842 | 10.63800 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | 13.01367 | 14.18457 | 5.11949 | 5.14701 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | 55.37342 | 58.19067 | 50.44565 | 41.25749 |

From the energies in the results table, it can be seen that the exo and endo form of the cyclopentadiene dimer are the thermodynamic and kinetic products of the dimerisation. Experimental data suggests that the major product of the dimerisation is the endo product[3], this suggests that the reaction proceeds via kinetic control and that the transition state for the kinetic product is of lower energy than its thermodynamic counterpart.

Transition States of the Exo and Endo forms of the cyclopentadiene dimer

An energy calculation for the transition states of the endo and exo forms was performed using gaussian with the Hartree-Fock (HF) method and 6-31g(d) basis set in order to ascertain that the reaction is under kinetic control, i.e. the endo transition state is of lower energy than its exo counterpart. The Hessian method was utilised, where a guess structure was initially created and optimised before optimisation to a TS(Berny) was performed. Below is a summary table of the results as analysed on gaussview.

| Transition state | ||

|---|---|---|

| TS vibrational motion |  |

|

| File Name | endo_hf | exo_hf |

| File Type | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RHF | RHF |

| Basis Set | 6-31G(d) | 6-31G(d) |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| Energy (a.u.) | -385.51843516 | -385.51436247 |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00002202 | 0.00000630 |

| Imaginary Freq | 1 ( -727 cm-1) | 1 ( -778 cm-1) |

| Dipole Moment | 0.3623 | 0.2487 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Computational Time | 4 min 17 sec | 4 min 18sec |

| Log File in Dspace | [Endo TS] | [Exo TS] |

| Item Table | Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000025 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000008 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001192 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000302 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-7.703143D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000016 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000003 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000547 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000141 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.225450D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

|

The convergence affirmation as well as the relatively low RMS Gradient Norm suggests that transition state sctucture optimisation has been completed. The TS vibrational motion also indicate the concerted pericyclic Diels Alder reaction. From the results table above, it is clear that the endo transition state has a lower energy then the exo transition state. In order words, reactions going through the endo transition state has a lower activation energy barrier and the reaction can therefore be said to be under kinetic control. Since the major product of the cyclopentadiene dimerisation is the endo form, based on the molecular mechanics and quantum mechanics energy calculations, it can be concluded that the reaction pis under kinetic control.

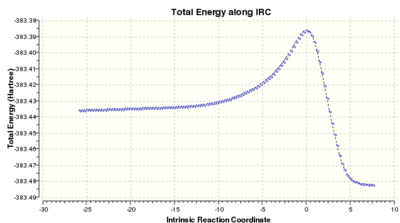

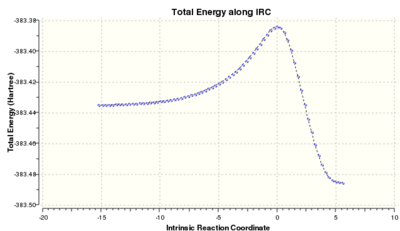

There are also two possible products for the partial hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer. From experimental data, it has been reported that the hydrogenation of the carbon double bond in the nobornene proceeds several times faster than the double bond of the cyclopentadiene, i.e. molecule 4 is the major product of the initial hydrogenation product.[4] Table 1. above reports the results from the molecular mechanics calculation and it can be seen that molecule 4 is the thermodynamic product. Therefore, it can be concluded that the partial hydrogenation of the dimer is under thermodynamic control. For interest purposes, an Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) calculation is included below to reveal the reaction profiles.

| Endo Transition State | |

|---|---|

| Reaction Profile | Reaction Animation |

|

|

| Exo Transition State | |

|---|---|

| Reaction Profile | Reaction Animation |

|

|

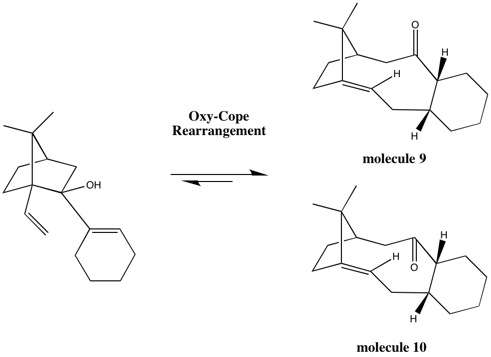

Atropisomerism is an important concept whereby restrictions of free rotation about a carbon-carbon bond, due to factors such as sterics, gives rise to stereoisomers that can therefore be isolated.[5] Naturally, the differences between stereoisomers are key considerations for synthesis of possible drug molecules such as Taxol. Molecules 9 and 10 below, are intermediates to the total synthesis of Taxol and are examples of atropisomers. The particular molecule have isomers that depend on the particular orientation of the carbonyl group, where 9 and 10 have their carbonyl group pointed up and down respectively. It has been reported that the intermediates 9 and 10 are formed via an oxy-Cope rearrangement that is in equilibrium.[6] Therefore, the reaction is under thermodynamic control and the major product would be the more stable atropisomer with the lower energy.

For bicyclic systems, it has been suggested that the molecule would adopt the conformation which favours the stabilisation of the six-membered ring.[7] Paquette has suggested that barriers to rotation could be due to sterics from other functional groups on the cyclohexane ring and thus preventing ring-flip.[6] This results in many possible conformations of both the Taxol intermediate molecule 9 and 10, such as the two possible chair forms, the boat form and the twist boat form. It is expected that one of the two chair forms would have a lower energy as it is free from steric repulsion.

Avogadro was used to investigate the different possible chair conformations for molecule 9 and 10 using the MMFF94s Molecular Mechanics force field optimisation method and physical manipulation of the molecule in order to obtain the required conformer. The results can be seen below.

| Atropisomer | Molecule 9 | Molecule 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conformer | ||||

| Total bonding stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 7.68079 | 8.44134 | 7.59305 | 8.76655 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 28.28401 | 33.62008 | 18.80014 | 22.19870 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | 0.21018 | 3.41981 | 0.21389 | 5.47039 |

| Total van der Walls energy (kcal/mol) | 33.16667 | 35.38725 | 33.29776 | 36.44474 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | 0.30040 | 0.20116 | -0.05553 | 0.40343 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | 70.53690 | 82.73843 | 60.55161 | 74.74271 |

Both the first chair conformations provides the most stable form for their respective atropisomers, with the total energy values being 70.53690 kcal/mol and 60.55161 kcal/mol for molecule 9 and 10 respectively. Therefore, it can be concluded that the molecule 10 would be the more stable form of the taxol intermediate.

To understand the differences between the total energy between the molecules, a closer examination of the specific structure of the two lowest energy chair forms needs to be performed. The figure on the right lists each strain factor and their individual percentage contributions to the total energy. It can be seen that the major contribution to the total energy comes from the total angle bending energy and the van der waal's energy (together, they contribute >80% of the molecule's energy). The angle bending energy is a major difference between the two molecules (~10 kcal/mol). Inspection of the bond angle indicates that molecule 9 & 10 have one of the ring angles adjacent to the carbonyl group being 123.0° and 118.2° and therefore far from the ideal tetrahedral angle of 109.5°. The latter is closer to the ideal angle, hence has a lower, angle bending energy and hence is slightly more stable. The 3D model is included for examination below. The highlighted green atom indicated the position of the unfavourable bond angle.

The van der waal's energy contribution can be seen a high factor in the total energy of the molecule. The reason is likely to be due to the numerous unfavourable interactions that exist in the structure. An example is highlighted for two hydrogen atoms where their interatomic distance is below the acceptable 210 nm and hence repulsion is experienced.

| Taxol derivative 9 | Taxol derivative 10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hyperstable alkenes

Bredt's rule states that molecules with double bonds located at the bridgehead positions of bridged ring systems or ring systems having trans double bonds are unfavourable due to a combination of increased angle strains and torsional strains, unless the ring is large enough to accommodate the strain. The Taxol intermediate has a large enough ring system that allows reduction in strain from its trans double bond. In essence, the surprisingly low reactivity of the double bond is an example of a 'hyperstable alkene'. The reason is because upon addition reaction (such as hydrogenation) of the double bond, the carbon atoms geometry change from sp2 to sp3 and therefore can no longer form a planar structure. Such change reduces the hyperconjugation it would otherwise experience when having the sp2 hyperdisation and an optimised angle of 120°. This makes the addition reaction of the hyperstable olefin a reaction with high activation energy and the product of the addition reaction having higher energy than the starting alkene reactant. An energy comparison between the a starting reaction of the Taxol intermediate (molecule 10) and its hydrogenation product (molecule 11) is given below.

| Molecule | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total bonding stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 6.42392 | 7.59305 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 22.28416 | 18.80014 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | 9.19804 | 0.21389 |

| Total van der Walls energy (kcal/mol) | 31.29812 | 33.29776 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | 0 | -0.05553 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | 69.53462 | 60.55161 |

As expected, it can be seen that the total energy of the hydrogenated product is of higher energy (~9.5 kcal/mol) than the original alkene. Therefore confirming the hypothesis that hyperstablity in the alkene of molecule 10 exists. It is interesting to note that there is zero electrostatic energy contribution for molecule 11. This is likely to be due to the lack of carbon-carbon double bonds in the structure.

Spectroscopic Simulation using Quantum Mechanics

A computational NMR spectroscopy analysis was performed with another form of the Taxol derivatives (molecule 18). The derivative 18 was chosen instead of the derivative 17 due to the fact that considerations were given to the most stable conformer, as the most stable conformer would dominate the equilibrium and thus calculations performed using this conformer would be more likely to provide a closer representation to experimental conditions. The molecules were optimised in Avogardo using the MMFF94s Force Field method with steepest descent algorithm. The results can be seen below.

| Molecule | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total bonding stretching energy (kcal/mol) | 15.87704 | 14.39670 |

| Total angle bending energy (kcal/mol) | 35.25607 | 28.43105 |

| Total torsional energy (kcal/mol) | 14.48865 | 13.68975 |

| Total van der Walls energy (kcal/mol) | 53.71159 | 50.51910 |

| Total electrostatic energy (kcal/mol) | -7.11522 | -6.28445 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol) | 114.01572 | 102.25453 |

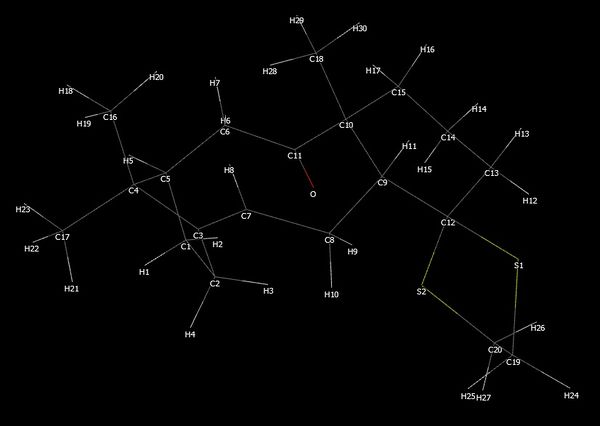

It can be seen that molecule 18 is a lot more stable than 17 and thus was selected for further analysis. A gaussian input file was created using the initially optimised molecule 18 with B3LYP method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set for further optimisation and frequency calculation, along with the inclusion of solvent effects and corrections for the energy for dispersion attractions and a command for NMR calculation (the input command: '# B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Opt SCRF=(CPCM,Solvent=benzene) Freq NMR EmpiricalDispersion=GD3') and the calculation was performed on the HPC. A 'simple wireframe' diagram with atom numbers labelled is included below to assist in examining the NMR data presented.

The calculated NMR shifts are compared with the literature values.[8] Solvent effects have been known to affect the NMR shifts, therefore in order to keep the consistency of the solvent system used the same as those used experimentally, benzene (C6D6) was selected as the solvent used for the calculation, as opposed to the standard system which is chloroform (Note: a NMR calculation had also been performed using chloroform as the solvent and the output file can be view here). The output file had been published on Dspace and can be viewed here. The computed NMR shift results can be viewed below.

1H NMR

As described above, the Taxol intermediate was optimised first in Avogadro and thereafter further optimisation was performed in gaussian with NMR calculations performed. The result for 1H NMR is tabulated below.

†Note: the guassian calculation does not take into account the fluxionality effects of symmetry-equivalent atoms. As such, the equivalent hydrogens, such as those in a methyl group, have been calculated as having different shifts, where in reality only one shift should have been observed. This error has been corrected by taking the average chemical shift between the equivalent hydrogens as the ppm vale for the collective hydrogens, along with the appropriate integration.

| Literature Value for 1H NMR spectrum of Taxol intermediate 18[8] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (ppm) | 5.21 | 3.00-2.70 | 2.70-2.35 | 2.20-1.70 | 1.58 | 1.50-1.20 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.03 |

| Integration | m, 1H | m, 6H | m, 4H | m,6H | t, 1H | m, 3H | s, 3H | s, 3H | s, 3H |

Although generally the generated NMR data has a good agreement, as stated above, the Gaussian NMR calculation fails to take into account fluxionality effects and so is unable to produce the correct peaks for multiplicity of the methyl groups.

A major deviation can be seen for the peak corresponding to hydrogen H(26), the alkene hydrogen. The reason is possibly due to the calculation's insufficient model of theory used to describe the orbitals of that particular part of the molecule and hence a poor description of the electron density. The basis set used was 6-31G(d,p), where the 'd' refers to the polarisation of the carbon atoms, where p and d character were merged. However, this produces a better representation for the sp3 hybridised carbon, whereas the alkene is of sp2 character and hence the calculation would produce a larger deviation from literature values compared to sp3 carbons. Improvements can be made is a more sophisticated basis set such as 6-311G++(2df,p) were to be utilised.

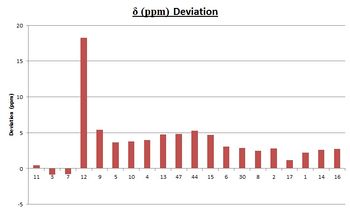

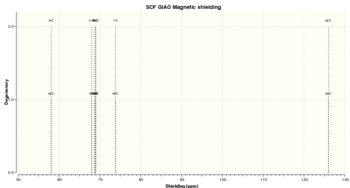

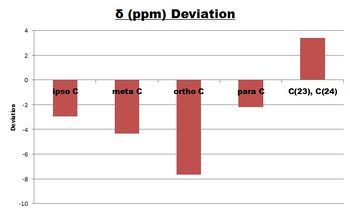

13C NMR

In a similar fashion to the proton NMR, the carbon 13 NMR was calculated with the same procedure and the results are tabulated below.

| Generated NMR Spectrum | Atom Number | Calculated 13C NMR shift | Literature Value [8] | Deviation Graph |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

11 | 211.92 | 211.49 |  |

| 3 | 147.86 | 148.72 | ||

| 7 | 120.12 | 120.9 | ||

| 12 | 92.84 | 74.61 | ||

| 9 | 65.93 | 60.53 | ||

| 5 | 54.93 | 51.30 | ||

| 10 | 54.75 | 50.94 | ||

| 4 | 49.53 | 45.53 | ||

| 13 | 48.03 | 43.28 | ||

| 47 | 45.64 | 40.82 | ||

| 44 | 44.00 | 38.73 | ||

| 15 | 41.47 | 36.78 | ||

| 6 | 38.51 | 35.47 | ||

| 30 | 33.69 | 30.84 | ||

| 8 | 32.46 | 30.00 | ||

| 2 | 28.35 | 25.56 | ||

| 17 | 26.50 | 25.35 | ||

| 1 | 24.45 | 22.21 | ||

| 14 | 24.00 | 21.39 | ||

| 16 | 22.57 | 19.83 |

The calculated NMR results show a general consistency with the literature data. Most of the results are with 5 ppm compared to experimental data. However, the deviation is almost 20 ppm for the carbon adjacent to the sulphur atoms (C(12)). This could be explained by the fact that sulphur is considered a 'heavy atom' and as such, exhibits spin-orbit couplings with the carbon atom. The B3LYP method used does not take into consideration the local magnetic field that is generated by the coupling and so produces a major deviation from experimental data. If this effect was corrected through the calculation, it would be expected that the deviation would not be as massive as 20 ppm.

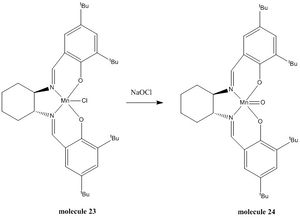

Analysis of the properties of the synthesised alkene epoxides

The counterpart of this 1C computational experiment is the 1S Laboratory Synthesis experiment. Two different asymmetric epoxidation catalysts, the Shi Catalyst and the Jacobsen Catalyst were synthesised and isolated in their stable pre-catalyst form (molecule 21 & 23 respectively). Thereafter the active form of the catalyst (22 & 24) were utilised to epoxidate two different asymmetric alkenes, including styrene and trans-stilbene to form styrene oxide and trans-stilbene oxide respectively. As both epoxide products have isomers, this section of the computational experiment investigates not only the structures of the catalysts and explores the epoxides, but also, attempts to ascertain the stereoselectivity of the catalysts when carrying out their epoxidation reactions.

Catalyst Structure

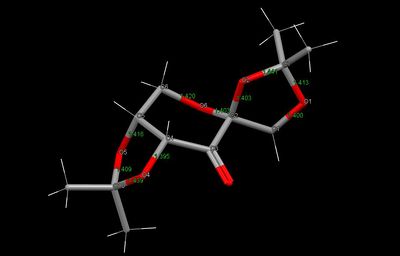

The Cambridge crystal database was searched using the Conquest software in order to search out the solid structure of the pre-catalysts (molecule 21 and 23). Their structures were analysed using the Mercury software and outlined below.

Shi's Catalyst

Shi's catalyst is an effectively asymmetric catalyst for the epoxidation of trans and trisubstituted alkenes due to steric control afforded by the acetal groups substituents.[9] As it is derived from D-fractose, a predominately six-membered ring containing an heteroatom (oxygen) atom, stereoelectonic effects, such as anomeric effects, become an important factor in the analysis of its structure.

Anomeric effects arises from the stabilisation achieved from the donation of the heteroatom lone pair into the σ* of the adjacent C-O bond based on the good alignment of the two orbitals and results in the substituent on the adjacent carbon preferring the axial orientation instead of the less inhered equatorial orientation.

The Conquest search returned with two results: NELQEA & NELQEA01, where the former crystal structure was selected for analysis. In order to examine possible anomeric effects in the molecule, C-O bond lengths were analysed. It is expected that a shortening of the normal C-O bond would be observed for enhanced stabilisation and lengthening for those that have electron density donated into its σ* antibonding orbital. Using the Mercury software and results are listed below.

The typical bond length for single C-O bonds are in the range of 1.42 Å.[10] Based on the bond length information, it can be seen that there are three different anomeric effects taking place in the shi's catalyst. The first originates from the oxygen (O(1)) lone pair donation into the σ*C(7)-O(2) orbital, resulting in the shortening of the C(7)-O(1) bond and lengthening of the C(7)-O(2) bond. The same case can be seen to be occurring between the aligned O(5) lone pair orbital and the σ*C(10)-O(4), resulting in the lengthening of the latter and the strengthening of the bond between C(10)-O(5). The last anomeric effect is shown to be happening between the lone pair of the O(6) and the σ*C(2)-O(2) orbital. The expected shortening of the C(2)-O(6) bond is observed, but interestingly shortening of the C(2)-O(2) bond is also seen. This could be explained by the reasoning that anomeric effect is also happening in the opposite direction, i.e. between the lone pair of the O(2) oxygen and the C(2)-O(6) bond. As such, stabilisation is achieved on both the C(2)-O(6) and the C(2)-O(2) bonds. Interestingly, the shortest C-O bond is actually the C(4)-O(4) bond. This is unlikely to be due to anomeric effects but rather is potentially due to induction effects from the carbonyl group.

Jacobsen's catalyst

Jacobsen's catalyst is a chiral catalyst which is selective for the epoxidation of cis-alkenes. It's selectivity originates from its chiral salen ligand which contains bulky tert-butyl groups that acts as directing groups for incoming alkenes. The particular geometry of the catalyst is due to the intermolecular interactions such as the Van der Waal's interactions between hydrogens, where attractive interaction is experienced by the hydrogens at a distance of around 2.4 Å. As the hydrogens get closer, nuclear repulsion starts to occur and this is typically evident at distances of around 2.1 Å.

Conquest search for Jacobsen's catalyst returned with two results: TOVNIB01 and TOVNIB02. The major differences between the two lies in the fact that for the hydrogens of the tert-butyl groups are staggered in the former search result, whereas in the latter, the hydrogens are eclipsed with respect to neighboring tert-butyl hydrogens. The catalyst crystal structures as analysed in the Mercury software can be seen below.

| TOVNIB01 | TOVNIB02 |

|---|---|

|

|

In addition, the Jacobsen's catalyst structure is also observed to be non-planar. This is likely due to the fact that the ligand adapts a di-equatorial arrangement from balancing the van der waal's interactions between all the hydrogens.

| TOVNIB01 | TOVNIB02 |

|---|---|

|

|

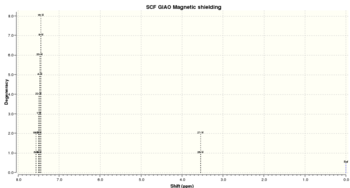

Epoxide NMR

In order to compute the NMR data, the specific epoxide was drawn and optmised, along with a frequency calculation performed. The operations was done using the B3LYP method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set with tight convergence criteria and chloroform as the solvent. Once the optimsation had been confirmed as successful, a command for the NMR calculation using the same level of theory was created and ran on the HPC. Along with a standard NMR computation, the spin-spin coupling (J-coupling) was also performed with the GIAO method with the mixed option for spin-spin coupling calculations, which improve the accuracy of the calculation by modifying the basis set to incorporate the Fermi Contact term.[11]

(S)-(-)-Styrene Oxide

As described above, two steps were required to compute the NMR data for styrene oxide. Firstly, the epoxide was drawn and optimised(optimisation output file can be view here). It should be noted that although the S enantiomer is used for the NMR, the R enantiomer should produce the same results for the NMR. The opposite enantiomer can be produced via 'Mirror Invert' funation in GaussView. Thereafter, the NMR command was performed. The results were published on Dspace and can be examined here. The labelled molecule of styrene oxide can be seen below.

1H NMR of Styrene Oxide

|

Hydrogen atom number | Computed NMR shifts | Literature δ (ppm) [12] | δ (ppm) Deviation Graph | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (ppm) | Integration | δ (ppm) | Integration |  | ||

| 1, 7, 9, 11 | 7.49 | 4H | 7.25 - 7.12 | m, 5H | ||

| 4 | 7.30 | 1H | ||||

| 17 | 3.66 | 1H (J = 1.3, 4.1 Hz) | 3.88 | dd, 1H (J = 2.6, 4.1 Hz) | ||

| 16 | 3.09 | 1H (J = 4.1, 6.0 Hz) | 3.16 | dd, 1H (J = 4.1, 5.5 Hz) | ||

| 15 | 2.54 | 1H (J = 1.3, 6.0 Hz) | 2.82 | dd, 1H (J = 2.6, 5.5 Hz) | ||

The computed NMR data shows close correlation with the literature experimental data. The slight deviation with the values (< 0.3 ppm) could potentially corrected by testing with a different basis set and method. The chemical shifts around 7 - 7.5 ppm are the hydrogens in the aromatic ring. Where literature data indicates all 5 hydrogens belonging to the multiplet of peaks around 7 ppm, the calculation appears to single out H(4) as different from the other aromatic hydrogens. Presumably, this is due to H(4) being in a closer proximity to the oxygen heteroatom and is shown to experience higher electron density and a stronger shielding effect, where in reality the aromatic hydrogens should be considered to be in the same environment and therefore deviation comparisons were performed using the average of the ppm values. The remaining three peaks are those of the non-aromatic hydrogens. As the hydrogens are all relatively close, coupling can be seen to exist between all of them (therefore, affording dd peaks). The calculated J-coupling values are in good accordance (H(17) - H(16) shows perfect correlation!) with the literature data and showing the expected relative J coupling values (H(15)-H(16) has the highest values due to closer distance and cis coupling H(17) - H(16) larger in value than the trans coupling H(17) - H(15)). It should be noted that the H(17) - H(15) coupling shows the biggest deviation from experimental values. It is likely to be the poor interpretation of the effects of the oxygen atom by gaussian and utilisation of another method and basis set could again improve the correlation.

13C NMR of Styrene Oxide

|

Carbon atom number | Computed NMR shifts δ (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) [12] | δ (ppm) Deviation Graph |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 135.0 | 137.2 |  | |

| 2 | 124.1 | 128.1 | ||

| 8 | 123.4 | |||

| 6 | 123.1 | 125.1 | ||

| 3 | 118.3 | |||

| 10 | 122.9 | 127.7 | ||

| 12 | 54.1 | 51.9 | ||

| 13 | 53.15 | 50.8 |

The 13C NMR of the styrene oxide molecule shows good agreement with the literature data, with the largest deviations being less than 5 ppm. Again, improvement of the deviation could be done by using a different method and basis set. It is worth noting that gaussian suggests C(2) and C(8) are in different environments, whereas in reality, due to symmetry of the molecule, the two carbons should be considered to be in the same environment. This is exemplified by the literature suggesting one chemical shift for the meta- position on the aromatic ring. The reason for gaussian suggesting different environments for these carbons is because the computation calculation does not take into account fluxionality effects and in effect only uses a static molecule , which in not the case in reality. Therefore, in effect, the 'real' calculated chemical shift should be considered to be the average of the two calculated shifts and this average was used in the calculation for the deviation from experimental data. The same case applies to the ortho- carbons ( C(3) and C(6) ).

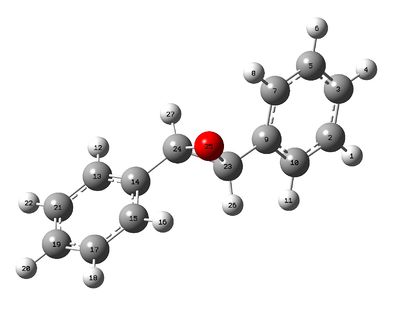

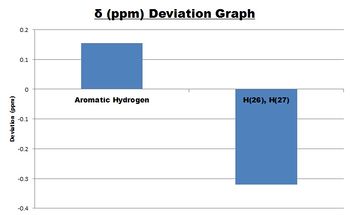

(R,R)-(+)-trans-Stilbene Oxide

The stilbene oxide molecule was first drawn and optimised (the output file can be view here). Thereafter, the structure with the optimised geometry was utilised to compute the NMR data and the spin-spin coupling values (although the characteristic NMR peak is a single and therefore no significant J-coupling were observed). Again, the other enantiomer would give the same NMR data and could be accessed using the 'mirror invert' function in GaussView. The NMR data were published on Dspace and can be accessed here. The stilbene oxide molecule with atom labels can be seen below.

1H NMR

|

Hydrogen Atom Number | Computed NMR Shifts | Literature δ (ppm)[13] | δ (ppm) Deviation Graph | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (ppm) | Integration | δ (ppm) | Integration |  | ||

| 6, 18 | 7.57 | 2H | 7.26 - 7.45 | m, 10H | ||

| 11, 12, 1, 22, 4, 20, 8, 16 | 7.48 | 8H | ||||

| 26, 27 | 3.54 | 2H | 3.86 | s, 2H | ||

It can be observed that the Gaussian calculation has suggested that the hydrogen atoms H(6) and H(18) are of different an environment from the rest of the aromatic hydrogens. The reason is likely to due to the fact that the computational method uses a static picture of the molecule (where in reality fluxionality would normally be observed). Therefore, the excluded hydrogens experiences a 'permanent' stronger electron shielding effect from the oxygen atom and hence are shown to be further downfield. Nevertheless, the calculation overall shows a good correlation with the literature data with the biggest deviation being just over 0.3 ppm.

13C NMR

|

Carbon Atom Number | Computed NMR Shifts (ppm) | Literature δ (ppm) [13] | δ (ppm) Deviation Graph |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14, 9 | 134.04 | 136.99 |  | |

| 5, 17 | 124.20 | 128.19 | ||

| 21, 2 | 123.49 | |||

| 13, 10 | 123.21 | 128.44 | ||

| 15, 7 | 118.35 | |||

| 19, 3 | 123.15 | 125.4 | ||

| 23, 24 | 66.2 | 62.81 |

The computed 13C NMR results agrees well with the literature data, with the biggest deviation being < 8 ppm. The biggest difference in value is down to the carbon atoms C(15) and C(7) which are slightly lower then what is expected. It is reasonable to suggest that due to lack of fluxionality considerations, the oxygen atom's inductive effects renders the carbon atoms less shielded and hence more upfield.

The Absolute Configuration

The configuration of the epoxide synthesised can be established using chiraloptical properties. Some of the properties that can be used to ascertain the chirality of the epoxide include the optical rotation at specific wavelengths (ORP), the electronic circular dichroism (ECD) and the vibrational circular dichroism (VCD). Computational methods are now available for the determination of these values and thereby provide information on the stereoselectivity of the epoxidation catalysts. Due to the fact that epoxides do not have appropriate chromophore exists for providing meaningful data for ECD, this method was neglected and efforts were put in to compute data for ORP and VCD. Where the former method is used extensively today, the latter method is used rarely. As such experimental VCD data are not commonly found and the computational data is included for completion.

Optical Rotation (ORP)

The optical rotation data was computed by using the previously optimised epoxide molecule and running an optical rotation calculation by using the Cambdrige version of the B3LYP method which produces a more accurate chiral-optical property result compared to the standard B3LYP. The keywords polar(optrot) were inputted for calculation of the optical rotation at wavelengths of 589 nm and 365 nm (the former is the standard sodium D line) using the CPHF=RdFreq keyword. The opposite enantiomer was obtained by using the 'mirror invert' function on GaussView. The results can be viewed below.

| Data | Wavelength | S-Styrene Oxide | R-Styrene Oxide | S,S-Stibene Oxide | R,R-Stilbene Oxide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computed value | 589 nm | 38.16° a[14] | -38.17° a[15] | -271.15°[16] | 271.15° [17] |

| 365 nm | 122.32° a | 122.34° a | 1140.82° | 1140.82° | |

| Literature value | 589 nm | 32.1° [18] | -24° [19] | -249° [20] | 250.8° [21] |

a Note: the slight differences in the magnitude of the optical rotation is likely to be due to intrinsic calculation rounding errors. The values are listed as reported in the gaussian file, where the epoxide enantiomer structures are inverted using the 'Mirror Invert' function and are thus exact mirror images of each other

It can be seen that the computed values and the literature data correlates reasonably accurately. The signs of the optical rotations are all in accordance to the experimental values. For the stilbene oxide enantiomers, the magnitude of the calculated optical rotations relates closely with the experimental values. However, a bigger deviation can be observed for the styrene oxide molecule, in particular for the R-styrene oxide. This is likely due to the insufficient level of theory involved in solving the Schrodinger equations which would cause a large difference between the calculated value and the literature value to arise. As such, only ORP with a magnitude of >|100| can be successfully predicted with high confidence.

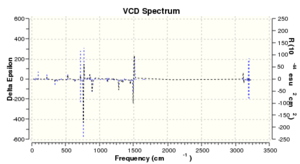

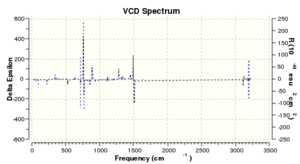

Vibrational Circular Dichroism (VCD)

Vibrational Circular Dichroism is another effective technique for determing the absolute configuration of the epoxides. VCD is a spectroscopic teachnique in which detection of the differences in the attenuation of the left and right circularly poloarised light of the incident light passing through the sample can be used to assign the chirality of the products.

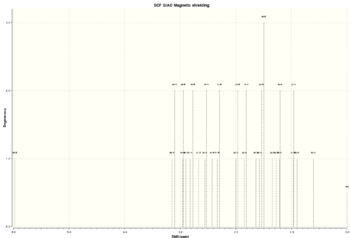

VCD spectrums of the epoxides under consideration were computed using Gaussian using the previously optimised molecules running a optimisation and frequency calculation with the specification of a vcd calculation using the B3LYP method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set and chloroform as the solvent. Additional keywords EmpiricalDispersion=GD3 integral=grid=ultrafine were also used.

| (R)-(+)-styrene oxide | (S)-(-)-styrene oxide |

|---|---|

|

|

| r-styrene oxide VCD Dspace link | s-styrene oxide VCD Dspace link |

| (R,R)-(+)-stilbene oxide | (S,S)-(-)-stilbene oxide |

|---|---|

|

|

| r,r-stilbene oxide VCD Dspace link | s,s-stilbene oxide VCD Dspace link |

As mentioned, although the VCD of these epoxides have been successfully computed, the lack of experimental data means that these results are not able to be compared. They are, hence, included here for completion purposes.

Comparion of VCD and ORP

Although optical rotation is a measurement that is widely used nowadays to determine the chirality of a chiral molecule. The technique itself is not without faults. Many of the results are manually read, as such they are prone to human errors. In addition, conditions such as temperature, solvent, purity and reference points all add towards the error of the measurement.

On the other hand, techniques such as VCD are spectroscopy techniques which, compared to optical rotation, is much less prone to errors. Nevertheless, the technique is not utilised much today and so not much data is available to compare the computational results to. As such, powerful spectroscopy techniques like VCD can be considered as a standard technique to be used.

Transition State Analysis

An analysis of the transition states for each of the catalysts with the pair of epoxides are performed to obtain computational data on the enantiomeric excess (ee) for the epoxidation. The results are compared with experimental results in order to examine the extent in which computational studies can be used for obtaining important data on real reactions.

Shi Catalyst

Asymmetric epoxidation using Shi's catalysts yields eight different possible transition states. Six of the transition states are disfavoured due to steric repulsion. The two remaining two favoured transition states are the spiro transition state and the planar transition state. The spiro TS is favoured due to available stabilising interactions from the oxygen lone pair with the п* orbital of the alkene. It was found that the preference for the catalyst's selection for trans-substituted and substituted olefins originates from epoxidates forming via the spiro transition state.[9] As the specific enantiomer that is formed depends on the type of transition state that it passes through, by analysing the preferred transition state, information regarding the enantiomeric assignment can be obtain and compared with the other pieces of data, such as those of the optical rotation. Below is a list of transition state energies for comparison.

| S-Styrene Oxide | R-Styrene | S,S-Stilbene Oxide | R,R-Stilbene Oxide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) |

| S-Styrene Oxide (1) | -1303.733828 | R-Styrene Oxide(1) | -1303.730703 | S-Stilbene Oxide (1) | -1534.683440 | R-Stilbene Oxide (1) | -1534.687808 |

| S-Styrene Oxide(2) | -1303.724178 | R-Styrene Oxide(2) | -1303.730238 | S-Stilbene Oxide (2) | -1534.685089 | R-Stilbene Oxide (2) | -1534.687252 |

| S-Styrene Oxide(3) | -1303.727673 | R-Styrene Oxide(3) | -1303.736813 | S-Stilbene Oxide (3) | -1534.693818 | R-Stilbene Oxide (3) | -1534.700037 |

| S-Styrene Oxide(4) | -1303.738503 | R-Styrene Oxide(4) | -1303.738044 | S-Stilbene Oxide (4) | -1534.691858 | R-Stilbene Oxide (4) | -1534.699901 |

Styrene Oxide

It can be seen from the table above that the lowest energy values are the S-Styrene TS (4) and the R-Styrene TS (4). Furthermore, by using the equation ΔG=-RTLnK, the equilibrium constant can be calculated. The difference in energy going from the S-enantiomer to the R-enantiomer is 4.59x10-4 a.u. or 1.205 kJ/mol. Therefore the equilibrium constant,K, is 0.615. In other words, the equilibrium, based on the data given favours the formation of the S-Styrene TS. The enantiomeric excess can be calculated using the equation:

This suggests that the epxoidation reaction using Shi's catalyst with styrene produce an enantiomeric excess of 23.84% in favour of the S-styrene Oxide. This does not agree with the literature values in which an ee value of 24.3% in favour of the R-styrene was reported and the experimental results performed in the synthesis counterpart to this experiment (1S).[22] This is likely due to the inadequate use method and basis set, coupled with the massive effect in which the solvent, temperature and pH has on the product results. Further improvement could be performed by varying the paremeters to optimise these factors, as well as using a different method of theory for the calculation. In addition to this, the literature data is known to make mistakes. The process of the measurement requires the experimenter to be ascertain of the purity of sample. Also, their comparison to previous literature is also a source of potential error, as their determination of the R- and S- enantiomer is based on comparing the measure value with reported data. Moreover, the literature data reports experimental ee values with a wide range, which further increases potential for error. Further discussion is included in the 'comparison of Di-substituted alkenes and terminal alkenes' below.

Stilbene Oxide

The free energy table above suggests that the most stable form of the TS for both the S-stilbene oxide and the R-stilbene oxide is TS 3. The difference in the change in free energy, going from the S-form to the R-form, is -6.219x10-3, or -16.33 kJ/mol. The equilibrium constant, K, is therefore, 726.19. In other words, the equilibrium lies strongly to the R,R-stilbene form. The enantiomeric excess can be calculated using the formula below:

The calculated ee value for R-stilbene is 99.72%, which is in agreement with the literature value of 95.5%, suggesting the computational method is sufficient for the calculation of ee value for di-substituted alkenes.

Comparison of Di-substituted alkenes and terminal alkenes

| Molecule | Stillbene oxide TS | Styrene oxide TS |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum difference in ΔG (kJ/mol) | 44 | 27 |

| Ratio for thermal fluctuation | ~6.59 | ~0.48 |

The literature comparison for the epoxides above suggests that the computational method can be seen to be sufficiently accurate for trans-alkenes but inadequate for terminal alkenes. The reason for this could be due to the fact that as the enantioselectivity depends on the energy difference between the secondary interaction between the olefin substituent and the spiro cyclic ketal ring of the catalyst. For terminal alkenes, the energy difference is relatively closer than for di or tri-substituted alkenes. As a result, the Gaussian calculation for determining the enantiomeric excess of terminal alkenes is more prone to errors and a slight miscalculation in the contribution of intermolecular interactions due to innate assumptions of the system can easily swing the equilibrium dominance to the opposite enantioisomer from those obtained in experimental studies. For example, the biggest energy difference between the stilbene oxide transition states is ~44kJ/mol, whereas for styrene oxide transition states, it is only ~27 kJ/mol. These data analysis results indicate that the transition states for the terminal alkenes are closer in energy.

Possible thermal fluctuation can be considered by calculating the ratio between the energy difference and kBT, where kB is Boltzmann's constant and T is temperature of the experiment. If this value is below 10, thermal fluctuations play a role in the process of determining the possible low energy transition states. The ratio for styrene oxide and stilbene oxide is ~0.48 and ~6.59, respectively, thereby suggesting styrene oxide is more likely to experience thermal fluctuation than stilbene oxide and therefore the computational method is more likely to produce deviations from literature.

Jacobsen Catalyst

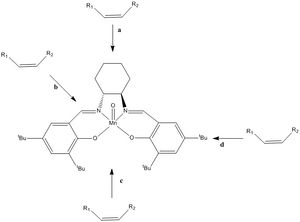

Four different transition states are possible for the asymmetric epoxidation of alkenes using the Jacobsen's catalyst, depending on the enantiomer and the orientation in which the alkenes in relation to the catalyst.

The alkene is thought of to orientate in a 'side-on' approach fashion to the catalyst, where a few different paths are possible. The trajectory along the a and c were thought of as unfavourable due to steric hindrance from substituents such as the tert-butyl groups. Although path d is acceptable as it offers п-п stacking, albeit, more sterically hindered, the Paths b trajectory where the alkene travels over the imine ligand was later proposed by Katsuki [23] and generally accepted as the correct path of attack due to favourable π-π interactions. In addition, computational and crystallographic studies performed by H. Jacobsen and Cavallo suggests that the catalyst is non-planar due to di-equitorial ligans formation.[23] The table below lists the transition state free energies which can be used to perform enantiomeric excess estimations.

| S-Styrene Oxide | R-Styrene | S,S-Stilbene Oxide | R,R-Stilbene Oxide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) | Transition State | ΔG (a.u.) |

| S-Styrene Oxide (1) | -3343.969197 | R-Styrene Oxide(1) | -3343.960889 | S-Stilbene Oxide (1) | -3574.923087 | R-Stilbene Oxide (1) | -3574.921174 |

| S-Styrene Oxide(2) | -3343.963191 | R-Styrene Oxide(2) | -3343.962162 | ||||

Note: Only 1 transition state data were provided for the S and R form of stilbene oxide

Styrene oxide

From the data table, it can be seen that the most stable transition state for S-styrene oxide and R-styrene oxide are TS 1 and TS 2 respectively. The energy difference between these two transition states is 7.035x10-3 a.u. or 18.47 kJ/mol. Since ΔG=-RTlnK, for an equilibrium going from the S-enantiormer to the R-enantiomer, the equilibrium constant, K, would be 5.808x10-4. This suggests that the enantiomeric excess would be:

The literature suggests an ee value of 86%.[24] This suggests that the correlation between the literature and computed values are close. The small deviation is likely due to experimental conditions such as temperature, pH and solvent used. Further improvements can be done by varying the calculation parameters.

Stilbene oxide

There are only one transition states for each of the S-stilbene oxide and R-stilbene oxide molecules. The change in energy, going from the S to the R enantiomer is -1.913x10-3 a.u. or -5.023 kJ/mol. The equilibrium constant, K, is therefore 7.586 (i.e. the equilibrium lies to the S-enantiomer, which is consistent with the comparison in energy, as the R-enantiomer is of lower energy and hence more stable). The enantiomeric excess can be calculated as:

The literature reported ee value is 27%.[25] In order to correct for a better correlation, a different method and basis set could be used. In addition, the ee values have been shown to vary extensively due to factors such as temperature and solvent used. These corrections could be corrected by using a different input command. Also, the Jacobsen catalyst in the transition state have some of its ter-butyl groups replaced by hydrogen (presumably to save computational time). The reduction in steric effects would have an effect on the energy of the transition state and since the ee value is derived from the free energy comparisons, the change in transition state structure would be expected to alter the final calculated value and hence enhance chances of deviation from experimental data.

Interactions in the active sites

Reactivity can be investigated by examining the electron density of transitions states. Two complementary computational methods, including the Non-covalent interaction (NCI) analysis QTAIM analysis are utilised below to investigate the transition state with the Shi's catalyst and S-styrene oxide.

Non-covalent Interactions (NCI) analysis

Transition states are often stabilised via secondary interactions, many of which include interactions such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions and dispersion interactions. These interactions can be modelled by analysing the electron density. The checkpoint file with the transition state with the Shi's catalyst and Jacobsen's catalyst and styrene have been obtained and by performing a calculation on a new cube with the selections 'Type = total density and Grid = Medium'. The results are presented below.

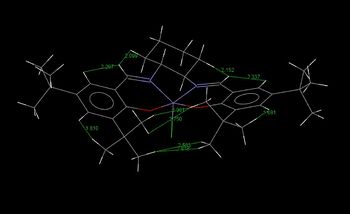

Shi catalyst

|

| |||||||

| 3D Jmol of Shi TS with NCI displayed |

The NCI analysis indicates that there are numerous secondary interactions involved in the transition state, which contributes to its stabilisation. For instance, attractive hydrogen bonding and van der waal's interactions can be seen in the Shi catalyst structure in controlling the geometry of the molecule. In addition, large amounts of attractive secondary interactions is observed between the catalyst and the alkene molecule, thereby stabilising the transition state and opens up the reaction site for the formation of S-styrene oxide.

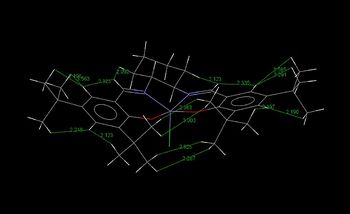

Jacobsen catalyst

|

| |||||||

| 3D Jmol of Jacobsen TS with NCI displayed |

Many non-covalent interactions can again be observed. The most pronounced it the п-п stacking interaction between the phenyl groups of the styrene and the catalyst in stabilising the TS as well as promoting the path along the imine as the point of entry for the epoxidation reaction. In addition, the repulsive interaction can be seen to force the alkene alignment as to form the S-styrene oxide. Last but not least, there are other numerous van der waal's attraction observed, such as those for the tert-butyl group, in stabilising the catalyst structure and morphing its geometry.

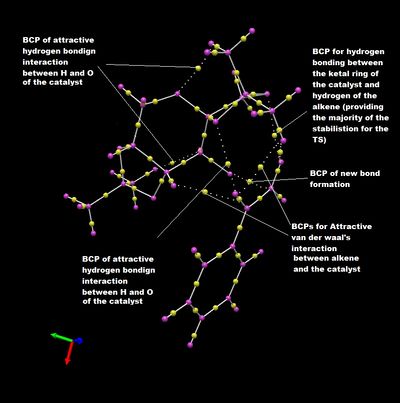

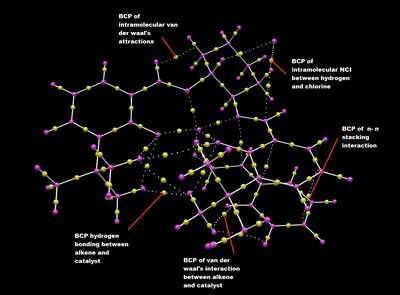

Electronic topology (QTAIM) analysis

The QTAIM analysis allows the electron density of the transition state to be further examined. Furthermore, it is possible to understand the position of the maximum electron density in a NCI, known as the bond critical point (BCP). Complementary, the the NCI analysis above, below is an QTAIM analysis of the same shi catalyst and Jacobsen catalyst transition state with styrene during the formation of S-styrene oxide.

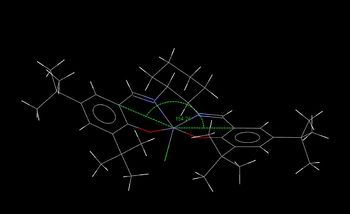

Shi Catalyst

As expected, the analysis indicates many bond critical points, attributing to the myriad of van der waals attraction and hydrogen bonding of both the intramolecular interactions of the catalyst and intermolecuar interactions between the catalyst and the alkene. These secondary interactions give rise to stereocontrol of the reaction.

A major concentration of BCPs are observed for the stabilising interactions between the oxygen of the ketal ring and the hydrogens of the terminal alkene on styrene, which complements the large section of secondary interaction as observed in the NCI analysis.

Interestingly, it can be seen that the BCP point, which indicates the maximum electron density in the NCI interaction, for a hydrogen bonding interaction is slightly closer to the hydrogen, which is contradictory to the electronegativity comparison. A possible explanation is that the calculation assume an 'electron density' for each atom and since the oxygen is a larger atom compared to the hydrogen atom, the overlap, which can be considered to be the secondary interaction, the crossing point, i.e. the maximum electron density would be closer to the hydrogen.

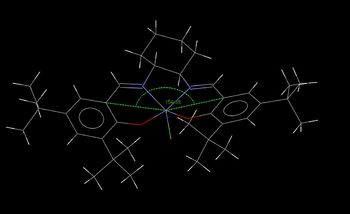

Jacobsen Catalyst

The QTAIM analysis of the Jacobsen transition state reveals several BCP. Of which, a few highlights the positions of the π-π stacking NCI and the hydrogen bonding and van der waals between the alkene and the catalyst, thereby confirming strong interactions exists which stabilises the transition state. Several BCP points are also indicated for intramolecular interactions for the Jacobsen catalyst, such as the van der waals of the tert-butyl group, and thereby helping the stability of the catalyst. Interestingly, attractive interactions can also be observed between the chlorine atom and the hydrogens nearby.

Suggesting New Candidates for Investigation

In addition to the epoxide computational study performed above, literature searches revealed (+)-Isoepiepoformin as a potential candidate for further investigation. It is synthesised from a derivative of the molecule 'cis-1,2-dihydrocatechols' and the starting material is readily available.

(+)-Isoepiepoformine has a molecular weight of 140.139 g/mol and a reported optical rotation of [α]D = +430.2.[26] This candidate is suitable as the magnitude of the experimental optical rotation is well above |100| and therefore computational methods are thus more reliable. Moreover, this molecule contains both an hydroxyl group and a enone component in this structure. The effects of these heteroatom groups on the optical rotation of the can thus be studied using computational methods. Furthermore, the absolute stereochemistry has also been reported with CD spectroscopy and thus computational methods can again be applied to compare with experimental results.

It should be noted that, although (+)-Isoepiepoformin is a naturally occurring molecule, its first total synthesis was only established in 2010. As such, its absolute configuration has not yet been checked computationally. This is further driving force which suggests that (+)-Isoepiepoformine is a good candidate for computational investigation. Last but not least, due to the potential complexity in the synthesis of (+)-Isoepiepoformine, there are currently no literature data for the other enantiomer ((-)-Isoepiepoformin), which suggests that it has not been synthesised. Computational studies of both of forms of Isoepiepoformin can thus prove to be valuable information complementary to future synthesis endeavors.

Conclusion

In this organic computation experiment, two major sections were explored, the first included examination of most stable conformer of the Diels-Alder dimerisation of cyclopentadiene and the hydrogenation of its dimer species. In addition, the NMR analysis and exploration of the atropisomerism of various Taxol intermediates were performed. In the second part, complementary to the synthesis component (1S) of this two part lab, computational studies of the epoxidation of alkenes with asymmetric epoxidation catalysts, including the Jacobsen and Shi catalysts were explored. A final word was given on possible new candidates for further study was also given.

Furthermore to the potential computational investigation on more epoxides, after discussions with Prof. Rzepa, it was highlighted that with the combined computational results from all the students undertaking the organic computational lab, a database can be created to investigate the absolute most stable Taxol intermediate (out of at least 12 different possible existing conformers). Such studies could prove to be very powerful in complementing experimental results in the process of investigating complex molecules, such as in drug discovery.

References

- ↑ A.G. Turnbull and H.S. Hull, Aust. J. Chem., 1968, 21, 1789 - 1797. DOI:10.1071/CH9681789

- ↑ R. Hoffmann , R. B. Woodward, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87(19), 4388–4389. DOI:10.1021/ja00947a033

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona and N. J. Kiwiet, J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52(8), pp 1469–1474. DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016

- ↑ M. Hao , B. Yang, H. Wang , G. Liu and S. Qi, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2010, 114, 11, 3811–3817 DOI:10.1021/jp9060363

- ↑ P. Lloyd-Williamsa and E. Giralta , Chem. Soc. Rev., 2001, 30, 145-157. DOI:10.1039/B001971M

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 S. W. Elmore, L. A. Paquette, Tetrahedron Lett., 1991, 32 (3), 319-322. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ W. F. Maier and P. von Rague Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,1981, 103 (8), 1891-1900. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 L. A. Paquette, N. A. Pegg, D. Toops, G. D. Maynard and R. D. Rogers, J. Am. Chem. Soc.,1990, 112 (1), 277-83 DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 O. A. Wong , B. Wang , M-X Zhao and Y. Shi J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 335–6338; DOI:10.1021/jo900739q

- ↑ J. Demaison and A. Csaszar, J. Mol. Struct., 2012, 1012, 7-14. DOI:10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.01.030

- ↑ http://www.gaussian.com/g_tech/g_ur/k_nmr.htm

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 A.Piccinini, S. A. Kavanagha and S. J. Connon, Chem. Commun., , 2012, 48,, 7814-7816 DOI:10.1039/C2CC32101G1

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 R. W. Murray and M. Singh, Org. Synth., 1997, 74, 91 DOI:10.15227/orgsyn.074.0091

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/28185

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/28184

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/28160

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/28200

- ↑ H. Lina, J. Qiaoa, Y. Liua, Z.L. Wu, J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym.,2010, 67, 236 - 241 DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2010.08.012

- ↑ D. C. Forbesa, S. V. Bettigeria, S. A. Patrawalaa, S. C. Pischeka, M. C. Standenb, Tetrahedron, 2009 , 65, 70 - 76 DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.019

- ↑ J. Read and I. G. M. Campbell, J. Chem. Soc., 1930, 2377-2384 DOI:10.1039/JR9300002377

- ↑ D. J. Fox, D. S. Pedersen, A. B. Petersena and S. Warrena, Org. Biomol. Chem., 2006,4, 3117-3119 DOI:10.1039/B606881B

- ↑ Z.-X. Wang, Y. Tu, M. Frohn, J.-R. Zhang, Y. Shi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1997, 119, 11224-11235 DOI:10.1021/ja972272g

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 E. McGarrigle, D. Gilheany, Chem. Rev., 2005, 105, 1563-1602 DOI:10.1021/cr0306945

- ↑ M.Palucki , P.J. Pospisil , W.Zhang , E.N. Jacobsen J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116 (20), 9333–9334 DOI:10.1021/ja00099a062

- ↑ E. M. McGarrigle and D. G. Gilheany, Chem. Rev., 2005, 105, 1563–1602 DOI:10.1021/cr0306945

- ↑ L. V. White, C. E. Dietinger, D. M. Pinkerton, A. C. Willi and M. G. Banwell, European Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2010 , 23, 4365 - 4367 DOI:10.1002/ejoc.201000642