Rep:Mod:Apple

COMPUTATIONAL LABORATORIES - AUTUMN 2008 - Module 1(Organic)

The basic techniques of molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital methods for structural and spectroscopic evaluations

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

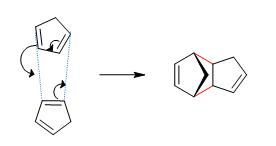

Cyclopentadiene dimerises via a pericyclic, [4πs+2πs] cycloaddition reaction. It is a type of Diels-Alder reaction, involving the movement of four π electrons through one of the molecules (acting as the diene) and two π electrons through the other (acting as the dienophile). The mechanism is as follows:

Figure 1 Mechanism of the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene

With all orbital symmetry rules associated with such a cycloaddition taken into account, there are two possible products able to form. One is the ‘endo’ dimer (1), formed via a compressed transition state, and the other is the ‘exo’ dimer (2), formed via an extended transition state. The two structures are shown below:

Pear2 |

1

Pear1 |

2

In the ‘endo’ form, the five membered ring of one of the pentadiene molecules sits below the conjugated system and the hydrogen atoms at the ring junction point up. In the ‘exo’ form, the ring points away, and the hydrogen atoms point down. Newman projections drawn along the bonds highlighted in red in figure 1 of the ‘endo’ dimer, show the three top carbon atoms of the front five-membered ring eclipsed with the two bridging bottom carbon atoms of the other five-membered behind. In the ‘exo’ dimer, these three top carbon atoms are staggered with the two bottom carbons of the ring behind, and only eclipsed with the single bridging carbon atom. This means less bulky groups are forced to eclipse, resulting in lower steric strain and lessened destabilising electron-electron repulsions. One would assume from this that the ‘exo’ form is the energetically favoured product.

Indeed, molecular modelling and ChemBio3D show the energy of the endo dimer to be greater than that of the exo dimer. ‘exo’: total energy: 31.8970 kcal/mol ‘endo’: total energy: 34.0153 kcal/mol The breakdown of energy contributions shows the most fundamental differences between the two structures are the greater torsional strain and destabilising dipole/dipole interactions present in the ‘endo’ dimer. These energies are higher because of the differences in staggering and eclipsing of the various groups, as described above.

One must conclude from this analysis, therefore, that the ‘exo’ dimer is the thermodynamically favoured, more stable product. However, it is the ‘endo’ dimer that predominates and only after considerable heating is the ‘exo’ dimer seen in any great proportion. This suggests the reaction is kinetically controlled, and the ‘endo’ dimer the kinetically favoured product. There must be some factor stabilising and lowering the energy of its transition state relative to that of the ‘exo’ dimer. This factor is known as secondary orbital interaction, and involves the bonding overlap of the HOMO of the diene and LUMO of the dienophile as the bond breaking and forming occurs.

One must conclude from this analysis, therefore, that the ‘exo’ dimer is the thermodynamically favoured, more stable product. However, it is the ‘endo’ dimer that predominates and only after considerable heating is the ‘exo’ dimer seen in any great proportion. This suggests the reaction is kinetically controlled, and the ‘endo’ dimer the kinetically favoured product. There must be some factor stabilising and lowering the energy of its transition state relative to that of the ‘exo’ dimer. This factor is known as secondary orbital interaction, and involves the bonding overlap of the HOMO of the diene and LUMO of the dienophile as the bond breaking and forming occurs. The diagram below shows this secondary overlap:

It is obvious that the overlap is not possible in the ‘exo’ dimer. This characteristic of Diels-Alder reactions is known, described and explained by the ‘endo’ rule.

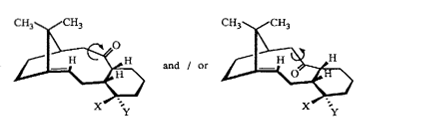

The ‘endo’ dimer can then be hydrogenated to give its dihydro derivatives. As there are two reactive double bonds present in the dimer, again, two possible products may be formed (compounds 3 and 4):

Pear1 |

3

Pear1 |

4

The MM2 force field can be used to optimise the structures and provide details of the energy breakdown of the two derivatives:

It can be seen from the table above that compound 3 is considerably lower in energy than compound 4 and the energy forms primarily responsible for this, are the bending and stretching vibrations (mainly bending) present in the molecule. The torsion terms are very similar, as would be expected because the two products are both ‘endo’ strcutures, but the energies of the bending and stretching vibrations, and to a lesser extent, the VDW and dipole/dipole, are much higher in compound 4 than compound 3. It is not, unfortunately, possible to determine which vibrations are responsible for the difference, and to what degree. However, some are more likely to be resposinle than others, and therefore, explanations for the differences can be proposed.

The contribution to the overall energy of a molecule by the process of molecular bond bending is calculated by Hooke’s Law: E=Σkθ(θ-θo)2. A higher bending energy value, therefore, will be for one (or both) of two reasons: it may be harder to make the bending motion in the first place (the kθ term is greater), or, the bond is perpetually being forced to deviate from equilibrium to a large extent (the θ-θo term is greater).

The difference between compounds 3 and 4 is the position of the double bond, and therefore, one possibility is that it is the bending and stretching associated with the double bond that causes the differences in energies. In compound 4, the double bond is part of both a five and six-membered ring. The six membered ring is slightly strained by the bridging carbon atom of the five-membered ring, as it is forced into its higher energy twist boat conformation. This makes the structure more rigid, resulting in a higher double bond force coefficient. In compound 3, the double bond is part of a comfortably orientated, planar, and therefore, more flexible, five membered ring.

However, the differences in energy may also be caused by the vibrations of the newly formed single bond. In compound 4, the new single bond is part of the five-atom carbon ring, now able to orientate itself in its energy optimum ‘open envelope’ configuration. In compound 3, it is part of the six-atom carbon ring, still forced into its relatively high energy twist-boat conformation. This more energetically favourable orientation present in compound 4 means that the new single bond is considerably stronger than that in compound 3, and distortions of it would result in higher energy inputs. In other words, the kθ is much higher for the single bond in compound 4.

It is important to note here that the use of molecular modelling is a useful tool in the calculation of other reaction properties. For example, the total energy values of two different structural or stereoisomers can be used in the Boltzmann equation to predict the proportions of products in a reaction mixture at a certain temperature. However, it does only provide thermodynamic data, and so the Boltzmann equation could not be applied to this reaction.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ analogue)

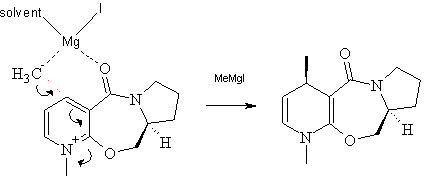

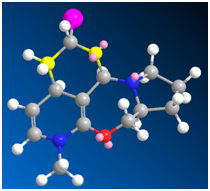

The nucleophilic addition to the optically active derivative of prolinol is as shown below:

....................5..............................................................6

Figure 2 Mechanism for the nucleophilic addition to a derivative of prolinol

The magnesium in MeMgI is highly electron deficient (coordination number of only 2) and therefore very keen to coordinate with available nucleophiles. The two lone pairs on the carbonyl oxygen of prolinol is an example of such a nucleophile. With the MeMgI coordinated to the carbonyl oxygen, the methyl group is now in the perfect position to bond with the desired carbon of the aromatic ring allowing the reaction to occur. Analysis of the reaction mechanism shows that the methyl group must, therefore, be on the same side as the oxygen relative to the aromatic ring.

This results in the stereochemistry seen in the final product.

Unfortunately, the ChemBio3D programme is unable to calculate the energies associated with the magnesium atom. In fact, it is unable to calculate the energies of any metal ion species. This highlights one of the considerable limitations associated with the use of this type of molecular modelling and energy minimisations: only a small proportion of all molecules can be analysed. As the energy of the magnesium ion cannot be calculated, it is not possible to minimise the energy of the reactant with the MeMgI coordinated to the carbonyl oxygen.

However, on minimising the energy of the final product 6, a structure is seen with the methyl group on the same side as the carbonyl group, though shifted as far away as possible. This is presumably to minimise unfavourable steric interactions and lone pair repulsions between the methyl group and carbonyl oxygen.

Figprodpart1 |

6 total energy: 28.8931 kcal/mol

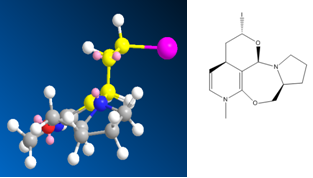

If, for the benefit of further investigation, the magnesium is replaced with a carbon atom to allow the calculation to run, a 3D image can be made showing how the methyl group (the carbon atom of the methyl group is highlighted in yellow on the left) will have to approach the aromatic ring on the same side as the carbonyl group (the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group is highlighted in yellow on the right) if it is indirectly attached to it.

In fact, additional analysis of this molecule shows that the better the alignment between the C-C bond of the methyl group and aromatic ring with the carbonyl bond, the lower the energy of the molecule. This is because it allows for the formation of the energetically favourable chair conformation in the transitions state (highlighted in yellow in the picture below). (Note: although interesting to see here, this perfect chair conformation would NOT form if a magnesium ion were to be present rather than the carbon atom because of its slightly different molecular orbital arrangement.)

The carbon atom highlighted aligns perfectly with the carbonyl oxygen allowing for a chair conformation and lower energy: 47.6441 kcal/mol

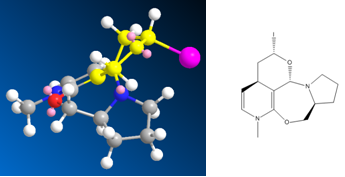

Here a twist chair conformer is seen because the atoms are not so well aligned resulting in a higher energy transition state: 51.8314 kcal/mol

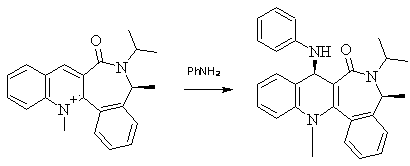

In the reaction shown below, a very different mechanism is seen. The nitrogen in aniline is, itself, a nucleophile possessing a lone pair of electrons and will therefore be repelled by the two lone pairs on the carbonyl oxygen. In this case, one would expect the nitrogen to approach the desired carbon of the aromatic ring from the other side to that of the carbonyl oxygen, resulting in the stereochemistry of the product shown. (The carbon is eletrophilic due to its para positioning relative to the N+Me group of the ring.):

Figure 3 Reaction scheme for the nucleophilic addition to a pyridinium ring

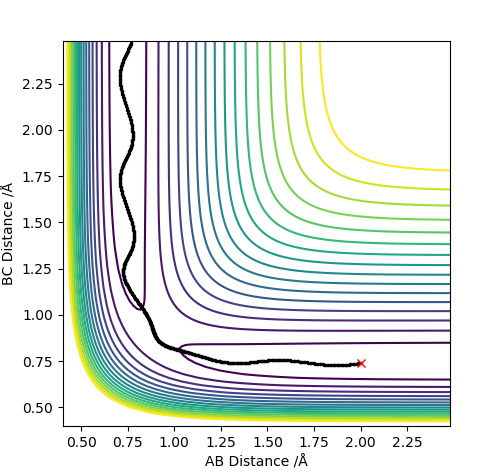

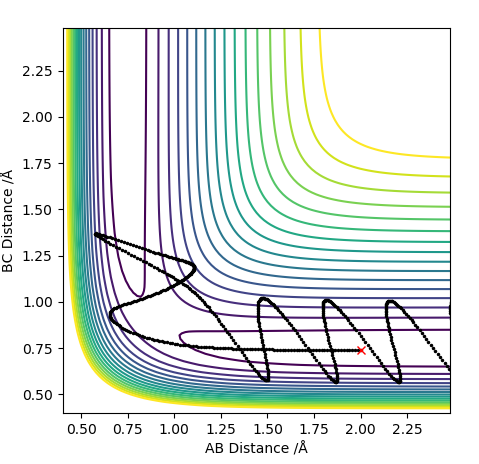

ChemBio3D and energy minimisation shows the carbonyl group in the reactant to be at a dihedral angle of 42.8o relative to the aromatic ring. One would expect therefore, that the NH2Ph molecule would approach from the other side of the aromatic ring at an angle of (90+42.8 =) 132.8o, relative to the carbonyl group. 90o is considered the optimum angle of approach, taking into account any steric hindrance associated with moving too close to the cyclohexane ring it is attacking.

The structure of an energy minima conformer of the product, following various testing, did indeed show the NHPh group to be angled considerably away from the carbonyl oxygen 8a: the carbonyl bond points away from the aromatic ring at an angle of 35.9o; the NHPh group points away from the aromatic ring at an angle of 135.8o. This makes the angle between them greater than 90o, implying the NH2Ph molecule did approach from the other side of the molecule. It must be remembered here, however, that molecular modelling cannot take into account the mechanisms and movements involved in a reaction; it only gives the lowest energy conformations of the start and final molecules, and so these results do not prove the theory behind the predicted mechanism.

Figprod2 |

8a

The energy of the product in which the NHPh group is on the same side as the carbonyl bond was shown to be greater by 4.2587 kcal/mol.

Figprod |

8b

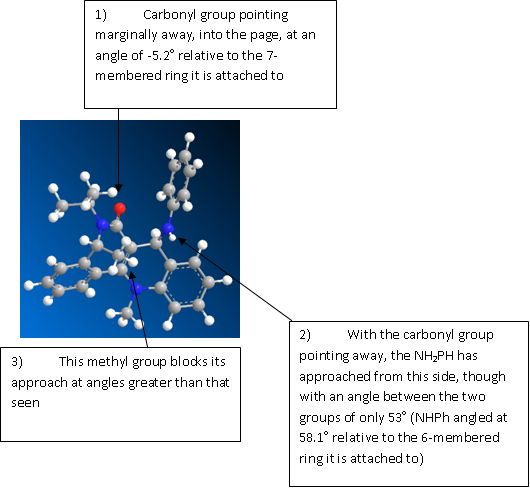

However, it was noticed that the energy resulting from 1,4-VDW forces is higher in the more favoured product. This is because the methyl group on the seven-membered ring is also on the opposite side of the carbonyl group, which would result in some unfavourable steric interactions and may work to block the approach of the NH2Ph from that side. Continued optimizations were attempted, and eventually an energy minimum product was obtained with the NH2Ph group appearing to have approached from the top of the molecule angled slightly to the other side of that of the carbonyl group but perpendicular to the methyl group behind (figure 4). When the methyl group was removed, the angle between the NHPh group and carbonyl group increased considerably. It may be, therefore, that a compromise is set up between the two factors, which determines the final position of the two groups relative to the carbonyl.

Figure 4

The snapshots of the molecules below show the differences between the two isomers and the available route of approach for the NH2Ph molecule. It can be seen that in 8a, the NH2Ph must approach from the same side as the large collection of atoms on the right side of the molecule. In 8b, this is not the case.

...................8a..............................................................................8b

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

An intermediate formed during the total synthesis of Taxol is a rare example of a molecule demonstrating atropisomerism. The two possible isomers of this intermediate are shown below, isomers 9 and 10. In both compounds, the olefinic proton is -cis to the bridging carbon of the five-membered ring,and syn to the protons at the two ring junction carbons. However, isomer 9 has the carbonyl group pointing down relative to the single, bridging carbon of the five-membered ring, whereas in isomer 10, it is pointing up.

Plumdown |

9

Plumup |

10

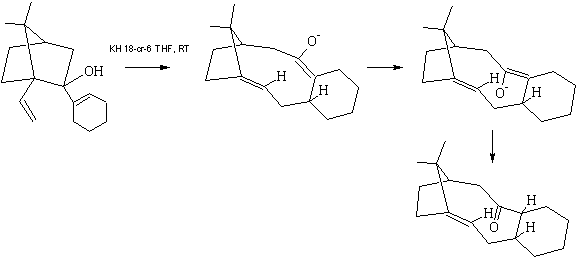

The reported reaction scheme for the formation of this intermediate is as follows [1]

.................................................................10-

Figure 5

It is apparent from analysis of this mechanism and the resulting stereochemistry of isomers 9 and 10 that the transition state involved must be that of the –endo chair configuration, as shown below in figure 6 and that isomer 10, or more accurately its deprotonated oxyanionic form isomer 10-, must always be formed first.[1]

Figure 6

Rotation then occurs to give the more energetically stable, thermodynamic product, isomer 9. When substituents are present on the cyclohexane ring, heat is often required to push this isomerisation forward, and sometimes, it will not isomerise at all. Note, a failure to isomerise is not always due to energetic barriers preventing it; the ‘carbonyl up’ isomer is, in some cases, more thermodynamically favourable. However, in the case of this molecule, where no substituents are present, isomer 1 appears to form directly, implying the isomerisation is easy even at room temperature [1].

In conjunction with expected results, molecular modelling and MM2 optimisation shows isomer 9 to be considerably lower in energy than isomer 10.

The reason for the added stability of isomer 9 is it is able to adopt the energetically favourable chair conformer rather than the more strained twist-boat conformer (figure 7)[2]

- .

.............'twist-boat'...................................'chair'

Figure 7

Analysis of the energy breakdown shows isomer 10 to have very high bending, stretching and torsional energies, all resulting from the more strained carbon framework.

Molecular modelling)[3] carried out previously showed the optimum structures of isomers 9 and 10 to be as shown below in figure 8, both structures very similar to those produced with ChemBio3D (note: the bridging carbon and its two methyl groups are missing in the picture on the right):

.........Isomer 9 .............................Isomer 10

Figure 8

These pictures again show the more strained carbon framework present in isomer 10. However, they can also help explain the higher values for non-bonding interaction energies seen in isomer 10. It can be seen in the picture of isomer 10 that the atoms of the cyclohexane ring are being forced back towards the atoms at the front of the cyclodecane ring. This results in considerable destabilising non-bonding steric interactions, which are not present in isomer 9 (similar to the exo and endo structures discussed in part 1).

It has been noted that the alkene in isomer 9 reacts abnormally slowly. Alkene bonds, when not conjugated with an adjacent carbonyl group, are nucleophilic, often undergoing electrophilic addition, for example with m-CPBA in epoxidation or Br2. However, at the same time as the alkene bond attacks the electrophile , there must be also be donation of a pair of electrons back towards one of the alkene carbon atoms, ensuring there is no unnecessary formation of a complete positive charge centred on it. This concurrent movement of electrons results in conjugation throughout the entire m-CPBA functional group and reacting alkene in the case of the epoxidation reaction and a three-member-ringed bromonium ion in the case of the reaction with Br2. This means, therefore, there must be a nucleophilic part within the electrophilic molecule. This is the OH bond in m-CPBA and a lone pair on the bromine atom undergoing nucleophilic attack in the reaction with Br2.

In isomer 9, due to steric crowding, an electrophile would have to approach and attack from the under-side of the molecule, opposite to the bridging carbon and its two bulky methyl substituents. However, this is on the same side as the very nuclephilic oxygen atom of the carbonyl bond. This means, therefore, that there will be great destabilising electron repulsions between it and the nucleophilic part of the electrophile. The electrophile would have to approach at exactly the right angle to get close enough to react with the alkene bond but avoid the carbonyl oxygen, greatly reducing the rate of the reaction. It may also be that the electrophile would react with the oxygen atoms instead, although this would not happen with m-CPBA or Br2.

Isomer 10, on the other hand would react much faster as any electrophile has a very unhindered approach to the alkene bond.

How One Might Induce Room Temperature Hydrolysis of a Peptide

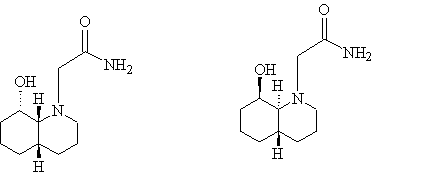

The two isomers shown below differ in their stereochemistry. Isomer 11 contains –cis decalin and isomer 12 contains –trans decalin. The cis and trans refer to the stereochemistry of the hydrogen atoms at the ring junction.

.......Isomer 11............................................ Isomer 12

One way in which these isomers differ is that –cis decalin is able to undergo ring inversion, during which one of the cyclohexane rings inverts. The –trans isomer, on the other hand, is not able to invert because it would result in both carbons of one of the cyclohexane rings being axial, which is not possible.

In the case of –cis decalin, therefore, there are four possible variations of the molecule: the OH group equatorial with the ethylamido group axial (11a); the OH group equatorial with the ethylamido group equatorial(11b); the OH group axial with the ethylamido group equatorial(11c); the OH group axial with the ethylamido group axial(11d). These four isomers are shown in the pictures below, together with their total energies:

Orangeaxmin |

11a 19.9695 kcal/mol

Orangeaxmaj |

11b 13.3792 kcal/mol

Orangeaxother |

11c 18.5235 kcal/mol

Orange8 |

11d 23.8969 kcal/mol

There are, however, only two possible orientations of –trans decalin: the OH group axial and then the ehtylamido group either axial (12a) or equatorial (12b). It is more energetically favourable for the OH group to be the group fixed in the axial position because it is much less bulky than the ehtylamido group, thereby, minimising 1,3 diaxial interaction. These two isomers and their energies are shown below:

Orangetransmaj |

12a 13.3579 kcal/mol

Orangetransmin |

12b 18.0974 kcal/mol

From the energies shown above, it can be seen that the lowest energy conformation is when both the OH and ehtylamido groups are in the equatorial position. This is because it minimises unfavourable 1,3-diaxial interactions to the greatest extent. Putting the OH group into the axial position increases the energy slightly, though to a lesser extent than if ethylamido group is put into the axial position. This is because the ethylamido group is much bulkier than the OH group and therefore will cause greater 1,3-diaxial instability (this conformation is not shown with the –trans isomer). The highest energy conformation is when both groups are in the axial position. As expected, 1,3 diaxial interactions would be very large in this case.

For the intramolecular peptide hydrolysis to occur, the OH group must be able to get close enough to the carbon of the carbonyl group within the ethylamido substituent, and at an appropriate angle. It can clearly be seen that in the –cis isomer, when both groups are in the equatorial position, the favoured conformation of all, both groups are pointing down at the same angle, allowing the oxygen of the OH group to reach close to the carbonyl carbon. Therefore, in this case, the majority of the reacting species are orientated in a conformation suitable for a reaction to occur. Furthermore, the hydrogen atom of the OH group is pointing perfectly towards the central nitrogen within the decalin ring. This would allow for hydrogen bonding to occur between these atoms, holding all reacting centres in the right position for reaction. This would greatly increase the rate of the reaction, lowering the half life to only 21 minutes[4].

In all of the other –cis isomer conformations, the ehtylamido group is pointing very much away from the hydroxyl group. Even when the OH group is axial and the ethylamido group is equatorial, and therefore, they are both pointing up, the distance and angle between them is substantial, especially between the carbonyl carbon and hydroxyl oxygen. It can also be seen that the hydrogen of the hydroxyl group is now pointing away from the central nitrogen, limiting the possibility for necessary hydrogen bonding. The highest energy, and therefore least favourable, conformer, in which both groups are axial, shows them pointing in completely opposite directions. Therefore, at room temperature the majority of the –cis reactant molecules are in the right orientation for reaction.

In the case of the –trans isomer, the lowest energy isomer is that with the OH axial and ehtylamido group equatorial. This would therefore, be the major conformer in a reaction mixture. In this conformation however, the OH group must point up and the ehtylamido group must point down clearly showing that the hydroxyl oxygen and carbonyl carbon are on opposite sides of the molecule and most certainly not in an orientation allowing for reaction. When both groups are axial, the two reacting groups are now on the same side of the ring and in a perfect position to react but this is a much higher energy conformation, and therefore isomerisation requires an energy input. Equilibrium will be greatly shifted towards the other isomer. However, this reaction will still occur because the both-axial isomer can form, only considerably more slowly than the –cis isomer.

However, in all cases, this reaction occurs much faster than is usually seen (the half life for hydrolysis of a peptide bond is around 500 years) and this is because of the way the reacting groups are able to orientate themselves closely and at a suitable angle, but more importantly, the hydrogen bonding involved between the hydroxyl hydrogen and central nitrogen atom within the declaim ring helps pull the molecule together and stabilise the transition state. This lowers the energy of activation, speeding up the rate of the reaction.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Dichlorocarbene, an electrophilic reagent, adds to compound 1 shown below via a regioselective [1+2] cycloaddition at the alkene bond endo to the chlorine atom. It approaches the molecule at the face opposite to that with the cyclopropyl ring. The reasons for this can be explained through analysis of its molecular orbitals.

Pink |

Compound 1

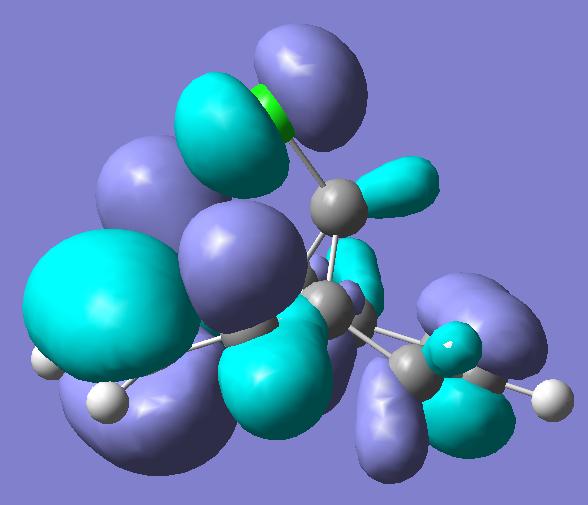

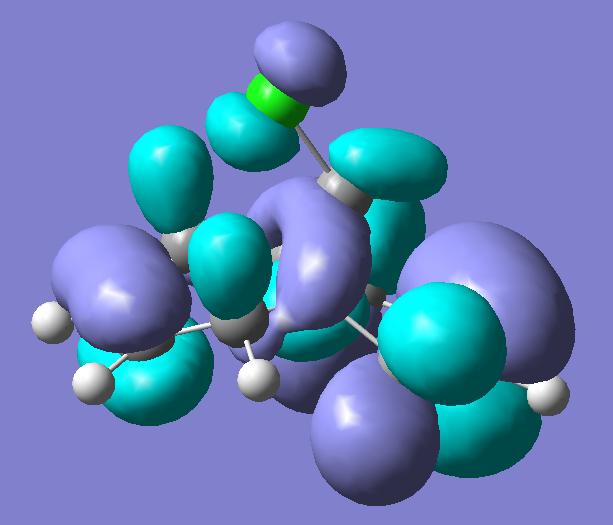

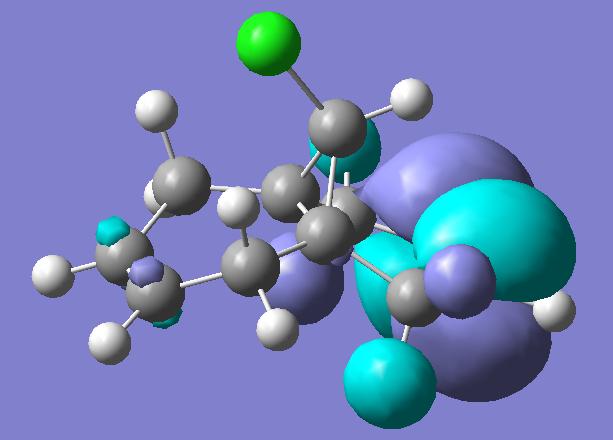

Previous computer modelling determined the energy of the HOMO-1 (figure 1b) orbital be 0.08ev[5] lower than that of the HOMO (figure 1a). The HOMO-1 orbital also shows considerable delocalisation with electron density spreading over onto the π-type cyclopropyl orbitals.

The lowering in energy of the HOMO-1 relative to the HOMO arises due to overlap and electron donation from the π orbital of the exo double bond into the anti-periplanar C-Clσ* orbital (LUMO+2, figure 1e), an overlap enhanced by the geometric distortion of the two rings (the exo-alkene double bond is 0.24A closer to the bridgehead carbon than the –endo-alkene double bond[5] ). This distortion also occurs due to the enhanced overlap of the endo π-orbital and cyclopropyl pseudo π-orbital.

The delocalisation of the HOMO-1 means the exo-π orbitals of the alkene bond are smaller (lower pπ coefficients) than those on the endo- π orbitals, rendering the endo bond more reactive to electrophiles. This can clearly be seen in the picture of the HOMO, which holds substantial electron density in the sterically accessible endo π-orbital. The pictures of the LUMO and LUMO+1 (figures 1c and 1d) show they are not affected by the distortions of the two rings, and play little role in the stereoselectivity of the compound’s reactions.

HOMO

Figure 1a

HOMO-1

Figure 1b

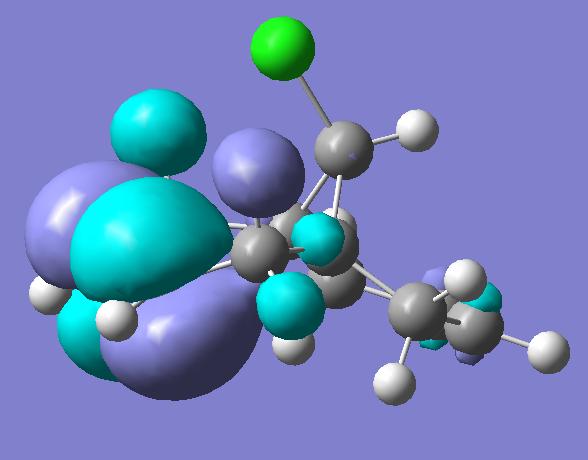

LUMO

Figure 1c

LUMO+1

Figure 1d

LUMO+2

Figure 1e

It is important to note that the energy of the transition state involved in the reaction at the exo alkene bond is in fact lower than that of the transition state of the reaction at the endo bond. This is primarily for the reason, although among others, of increased destabilising steric compressions present between the methylene protons in the endo transition state. This destabilisation must not be enough prevent the preferred attack at the –endo bond.

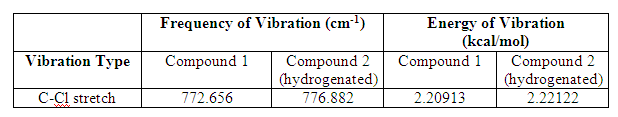

Analysis of the vibrational energies of the bonds within compound 1 and its hydrogenated form, compound 2 shown below, can help back up the proposition that the orbital interactions described above do occur. Donation of electrons from the exo π orbitals into the high-energy, anti-bonding C-Cl σ* orbital would weaken the C-Cl bond. One would expect, therefore, that on hydrogenating the alkene bond anti to the C-Cl bond, donation would not occur and the C-Cl bond would, thereby, be strengthened. This would result in a higher energy C-Cl stretching vibration.

Pink2 |

Compound 2

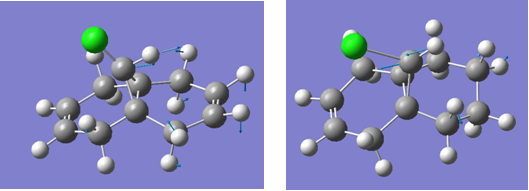

A number of vibrations appeared to involve some stretching of the C-Cl bond. However, movements were only slight and it was not considered that any differences seen in the corresponding vibrational energies could be predominantly attributed to the changes in orbital interactions involving the C-Cl bond. However, one vibration (figure 2) involved considerable C-Cl bond stretching and its energy was identified by an IR spectrum assignment software as typical of a C-Cl bond stretch. This, therefore, was used for the analysis and comparison.

Figure 2 The C-Cl stretch vibration used for analysis

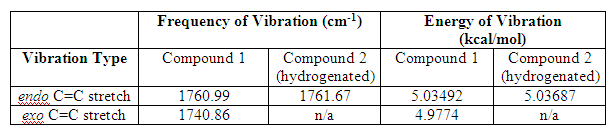

As the results in table 1 show, the energy of the C-Cl bond stretch in the hydrogenated compound is 0.01209kcal/mol higher in energy than the C-Cl bond in compound 1, supporting the theory proposed above.

Table 1

The energy of the endo alkene bond would also be affected by the hydrogenation of the anti-alkene bond, though to a much lesser extent. With no exo π orbital donation into the C-Cl σ*, the ring structure would not be so distorted and there would therefore be less overlap, and electron spread, between the endo π orbital and the pseodu π orbital of the cyclopropyl. This would result in another strengthening of the bond relative to the un- hydrogenated form. As can be seen in table 2, this was indeed the case, though perhaps one would expect a greater difference between the two. This may imply that the overlap described is only slight, and substitution of the energy difference into the Klopman-Salem expression would confirm this. Unfortunately, more information is required to do this here.

Table 2

The lower energy of the exo C=C bond stretch relative to the endo is also as expected. With considerable overlap into the C-Cl σ* orbital, the C=C π bond has reduced electron density and, therefore, reduced double bond character.

Structure Based Mini-Project Using DFT-Based Molecular Orbital Methods

The Origins of Stereoselectivity of the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert Reaction – the Intramolecular, (S)-Proline-Catalyzed Aldol Reaction

Introduction

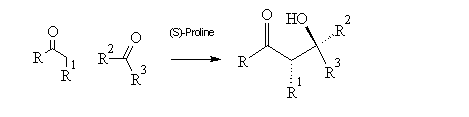

The Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction (figure 1) was the first invention of an asymmetric aldol reaction, involving high stereo- and enantio-selective organocatalytic transformation[6]. Research into organocatalytic reactions, especially those using catalytic α and β amino acids, has increased massively over the last few years due to their similarity to the reactions carried out by antibodies within living systems. Deatailed knowledge of their mechanisms could provide potential means for further drug development.

(a)

............1..................................................2...........................................3

...............4...............5..........................................6

Figure 1 Examples of Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reactions

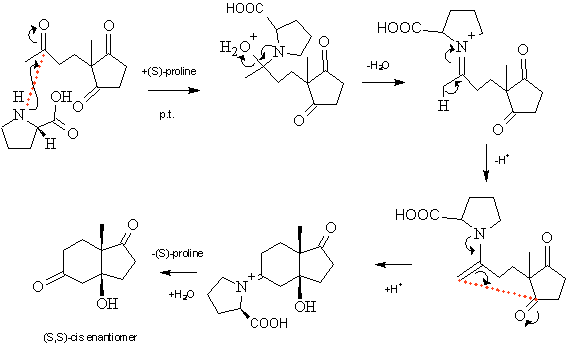

Since its discovery in the early 1970s, the intramolecular (S)-proline catalyzed aldol reaction (a) and its stereo-selectivity have been researched and modelled and many different proposals for its mechanism have been made (figure 2). However, there has been very little experimental evidence to support these proposals and only in the last couple of years has a mechanism involving a single proline molecule and enamine intermediate, suggested by Houk et al[7], been widely accepted as the most likely explanation for the reaction’s selectivity.

Figure 2 Proposed mechanisms for the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction

In this report, two of these mechanisms, the first proposed by Hajos[8], in 1974 and the final proposed by Houk et al in 2005, together with various other alternatives all employing enamine intermediates, have been investigated and computer modelling has been used to confirm the stereochemistry of the compound expected from the mechanism is that of the actual compound obtained by Davies et al during their research into β-amino acid catalysis[9].

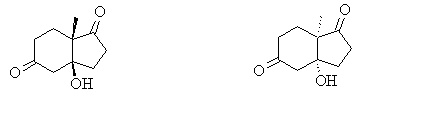

The final product of the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction is the enone (S)-3. This enone is the product of elimination of the bicyclic-ketol (S,S)-2, but its stereochemistry relative to 2 and the reactant 1 is subject to reaction conditions and is another topic of research altogether. This is, therefore, not investigated here and it is the ketol that is described as the ‘product’ throughout the rest of this report.

Background

The Original Mechanism involving an Enamine Intermediate

Research carried out by Hajos in 1974 worked to disprove the previously proposed mechanism[10] for the asymmetric synthesis using (S)-proline, which involved the formation of a protonated enamine and oxazolidine ring. Using circular dichroism measurements of his synthesised ketol, he had established three possible alternatives for its structure were possible: trans-fused; cis-fused with an equatorially orientated methyl group in the boat form of the six-membered ring (and axial hydroxyl group); cis fused with an axially orientated angular methyl group in the chair form of the six-membered ring (and equatorial hydroxyl group). X-ray diffraction studies then confirmed this final configuration was that adopted in the final product[8].

His reason for questioning the earlier mechanism was based on investigation with 18O labelled water. Although, the enamine mechanism would explain the stereochemistry of the product obtained, 18O water testing appeared to show such a mechanism did not occur. He, instead, proposed a mechanism involving ‘the addition of (S)-proline in its zwitterionic form to one of the carbonyl groups’ of the five membered ring as shown below:

It was suggested that a 6,7,7-membered conformation would be formed and held together by the two hydrogen bonds marked in red in the structure above. It was considered that the bulky (S)-proline would have to attach on the side of the molecule opposite to that with the methyl group and the pyrrolidine ring hydrogens would have to be on the same side to allow the two hydrogen bonds to form. This would force the hydroxide group onto the same side as the methyl group, allowing attack by the olefin bond to occur on the underside. This would result in the formation, almost exclusively, of a –cis fused product.

However, later research in 1976 [9], [11] questioned its stereochemical outcome. More importantly, this mechanism provided no information regarding the selectivity of the given enantiomer over the other, and also, as was discovered in this investigation, the selectivity of one of two possible conformations of that enantiomer over the other.

Work in the field continued and focus returned again to mechanisms involving enamine intermediates (for those interested, in 2004, new 18O incorporation studies by List et al showed that enamine formation is, in fact, a possible mechanism of reaction[6]).

In 2001, before his later work provided more substantive evidence, Houk carried out extensive computer modelling investigations into the transition states of all amine-catalysed aldol reactions involving enamine intermediates[12] in an attempt to provide reasons for their high stereo-selectivity.

In the case of simple primary amine catalysis, there was clear explanation for the seen –cis selectivity: with a methylamine catalyst (d), the energy of the –cis transition state was found to be 11kcal/mol lower than that of the –trans (figure 3[12]).

Figure 3 Reaction scheme for the methylamine-catalysed intramolecular aldol reaction and the transition states involving an enamine intermediate for the –cis (39d) and –trans (39e) isomers.

The optimised 3D models above show that in the transition state of the –trans isomer, the bulky methyl group is forced into the axial position, whereas in the transition state of the –cis isomer, it is equatorial. This results in considerable (1,3)-diaxial interations within the trans isomer transition state, destabilising it relative to the –cis. It can also be seen that the transition state of the –cis isomer is able to adopt an ideal half-chair arrangement, allowing for the formation of a short, strong hydrogen bond between the oxygen of the carbonyl undergoing attack and the hydrogen atom attached to the enamine nitrogen. In the –trans isomer transition state, the chair arrangement is slightly distorted and only a much longer, weaker hydrogen bond is able to form. This means less stabilisation of the –trans transition state relative to the –cis.

However, proline is a secondary amine and the hydrogen atom attached to the enamine nitrogen is, therefore, no longer present. Necessarily, the hydrogen bond is no longer a factor in stabilising the two transition states. When dimethylamine was used as a catalyst, the energies of –cis and –trans transition states were virtually the same.

It is now clear that the functional groups of the proline molecule, and their stereochemistry, play a considerable role in determining the stereochemistry of the final product, and as shall be seen, also control the preference of one enantiomer (and one conformer of that enantiomer) of the –cis isomer over another.

Analysis of the mechanism proposed by Houk in 2005 shows that the –OH group of the carboxylic acid moiety in (S)-proline is in the perfect orientation to hydrogen bond with the carbonyl group undergoing attack, once the proline molecule has formed the enamine. The transition states can, therefore, be considered just as they were with the primary amine as shown above; the hydrogen atom undergoing hydrogen bonding is simply a few atoms further along.

This effect of hydrogen bonding would explain, again, the preference of the –cis isomer over the –trans. However, it still does not delve into explanations for selectivity within the various enantiomers and conformers of the –cis isomer, and it is important, now, to discuss these and try to provide such an explanation.

In the ketol 2, there are two chiral centres and therefore, in theory, four diasteroisomers are possible: (S,S), (R,S), (S,R) and (R,R). However, due to the fairly rigid bicyclic structure of the molecule, the (R,S) and (S,R) enantiomers cannot form. However, the (S,S) and (R,R) enantiomers can, and as discovered, they also have different conformers, also all able to form. The (S,S) enantiomer, for example: it can have the methyl group either axial or equatorial and the hydroxyl group either axial or equatorial. The same for the (R,R) enantiomer. One might expect the (S,S) enantiomer and (R,R) enantiomer in which the methyl group is equatorial and hydroxyl group is axial would be the more stable product, due to reduced (1,3)-diaxial interactions.

However, as stated above the actual product has the methyl group in the axial position, seemingly destabilising it relative to the (R,R) enantiomer and the alternative (S,S) conformer, and making its transition state more like that of the –trans isomer (but with the stabilising hydrogen bonding present). The conformation of the actual product is not shown or discussed at all by Houk, he analyses its conformer with the methyl group equatorial, the reasons for which are not understood and have caused much confusion. However, it must be noted that his work in 2001 showed the transition states of the -cis and trans isomers, when dimethylamine was used as a catalyst, were virtually the same energy, despite having the methyl group axial in the –trans isomer and equatorial in the –cis. This suggests that having the methyl group axial rather than equatorial does not destabilise the structure in ways as would be expected.

For now, discussion of the two (S,S) conformations and the preference of the experimentally obtained conformer over its apparently more stable form will be left and returned to later on. First, the preference for the (S,S) enantiomer over the (R,R) must be established.

Fortunately, the transition states proposed by Houk in 2005[7] can again be used to suggest an explanation for the preference of the (S,S) enantiomer over the (R,R). Models of the two transition states are shown below. They have only been subjected to a MM2 optimisation, and are, therefore, not particularly accurate. However, they do serve to show the differences between the two structures:

.................2.............................................................7

ProjcisTS |

ProjcisaltTS |

MM2 found the (S,S) structure to be 1.11kcal/mol lower in energy than the (R,R) (literature: 2.20kcal/mol[7]).

It can be seen that in the (S,S) enantiomer, the –OH group of the carboxylic acid moiety is anti to the carbonyl oxygen, whereas in the (R,R) enantiomer (and –trans isomer), it is syn. As modelling by Houk showed, and as can be inferred from the structures above, the –anti- transition state is energetically favoured because its arrangement allows the hydrogen bonded atoms to be slightly further away, and therefore, at an optimum distance to allow the enamine to form its more favourable, planar geometry. In the syn transition structure, the hydrogen bonding atoms are forced closer together, meaning the carbon, NCCO2, holding the carboxylic acid moiety, is forced backwards, distorting the pyrollidine ring. This increased stabilisation experienced by the (S,S) conformer must be greater than the (1,3)-diaxial destabilisation. The transition state of the –trans isomer is destabilised by both (1,3)-diaxial interactions and pyrollidine ring distortion mentioned above, and therefore, never formed.

Furthermore, there is also some NCH to O hydrogen bonding within the two transition structures, which in the anti form is much stronger because the atoms are much closer together. In the –syn form, the compressed hydrogen bonding and distorted pyrollidine ring force the hydrogen atom of the NCH further from the carbonyl oxygen.

This, therefore, provides a mechanistic explanation for the seen stereochemistry of the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction:

Figure 4 Complete mechanism for the Intramolecular, (S) Proline-Catalyzed Aldol Reaction

However, none of the papers by Houk referenced here appear to have compared the chemical properties of the modelled structures with those of the actual product obtained in experiment; it appears he may have asked someone else to do this but the results cannot be found. Yet to be realised is the selectivity of the methyl-aixal conformer over the methyl-equatorial, which his models, indeed no-one yet, has appeared to explain.

Therefore, the two (S,S)–cis enantiomer conformers, the (R,R)-cis enantiomer and the –trans isomer of the product have been modelled, optimised (MM2, PM3, B3lyp/6-31G(d) and MPW1PW91) and chemically analysed by carbon (and proton) NMR, IR and optical rotation in order to make the comparison required and perhaps provide an explanation. This will help determine the accuracy of the proposed mechanism and confirm the stereochemistry of the product obtained. Unfortunately, enantiomers should not differ in their carbon and proton NMR and IR spectra (they were run anyway to check for differences), but the two (S,S) conformers should and calculations of all their optical rotations should be very different, allowing the complete conformation of the product obtained in experiment to be verified, something not seemingly done before.

The chemical analysis of the experimentally obtained product to be used in this comparison was carried out and reported by Davies et al[9]. Infrared and optical rotation data was also taken from Hajos et al[13]. CNMR data was not available from Hajos’ paper.

Results and Discussion

The modelled, optimised structures of the (S,S)-cis (methyl equatorial), (S,S)-cis methyl axial, (R,R)-cis (methyl equatorial) and –trans isomers of the product are shown in the 3D rotating images below with their associated energies:

Projcisaltopt |

(S,S) methyl-axial -cis enantiomer: -385957.03801kcal/mol

Projcisenantiomer |

(S,S) methyl-equatorial -cis enantiomer: -385957.39840kcal/mol

Projcisopt |

(R,R) methyl-equatorial -cis enantiomer: -385956.23813kcal/mol

Projtransopt |

-trans isomer: -385953.08166kcal/mol

Analysis of the energies of the four structures shown above is very interesting. It is immediately apparent that they are all very close in energy, perhaps with the exception of the –trans isomer, which, as expected, is the highest in energy. The difference in energies between the two –cis, methyl equatorial enantiomers is found to be only 1kcal/mol, which using the equation, ΔG = -RTlnK, gives an expected ratio of the two of 1:0.99, only minutely in favour of the (S,S) enantiomer. However, as mentioned above, mechanistic and chemical analysis of the product obtained from experiment suggests a much higher selectivity for the (S,S) isomer, and therefore, greater energy difference between the two. However, it must be remembered that the energies shown above are of the final products, which do not take into account mechanistic analysis. It is the energy of the transition state that is much lower in the (S,S)-cis enantiomer. One can perhaps conclude from this that the reaction is kinetically controlled.

It can also be seen that the (S,S) methyl equatorial conformer is lower in energy that the (S,S) methyl axial conformer, though by only 0.36kcal/mol Based on theory, this is as expected because of the reduced (1,3)-diaxial interactions, though of course, it is the (S,S) methyl axial conformer that actually forms. However, much more importantly, one can conclude from the similarities in energy between the two that, despite theoretical predictions, having the methyl group axial or equatorial in the product has no or little effect on the energy of the final structure and therefore will have no or little effect on the preferred formation of one conformer over the other. There must be some other factor involved in the transition states that control the formation of the (S,S) methyl axial conformer over the equatorial conformer, again suggesting the reaction is kinetically controlled. It is also, possible, perhaps that a racemic mixture of the two would be produced, because, although Hajos states the methyl group is axial, he does not mention the equatorial conformer involving a chair transition state (only that involving a boat transition state - maybe a methyl equatorial chair transition state is not possible!!??). It may also be the case that they can simply interconvert at room temperature, together with the (R,R) enantiomer, because again the differences in energy are minimal. One would have to analyse the energies of the transition states involved in the interconversions, however, to state this with any conviction.

Unfortunately, extensive examination of the two structures, and imagination of the various possible transition states and directions of approach of the alkene bond in forming the bicyclic ketone has provided no explanation for the preference of one conformer over the other. Sterics, boat/chair transition structures of the six-membered ring, transition structures of the five-membered ring, axial/equatorial approach and possible effects of atopisomerism have all been considered to try and explain this but no conclusions have been made. It is a shame that the transition states cannot be properly modeled to try and provide better information regarding the mechanism of formation of two conformers.

Taking everything into account however, the similarities in energy between all three structures and the unexplainable results could also imply the three modeled structures are limited in their quantitative accuracy, and should be kept in mind during analysis of their spectra and rotational properties.

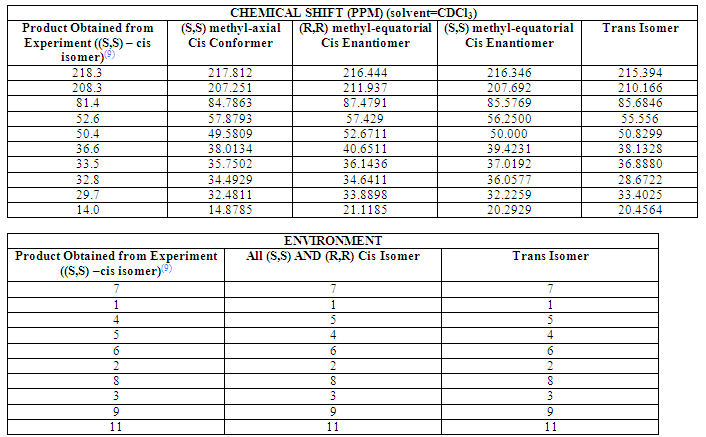

Carbon NMR

The results obtained from the carbon NMR are not perhaps as conclusive as one would expect: the spectra of the (S,S) axial-methyl –cis isomer is not massively alike to that of the product obtained from experiment. However, comparison with the other spectra would lead one to conclude that the product obtained from experiment is, indeed, the (S,S) axial-methyl –cis isomer, supporting the accuracy of the proposed mechanism. As an overall indication of the similarity between the actual product and three modeled structures, the differences between the shifts of each corresponding peak were calculated and summed. This value was considerably lower for the (S,S) axial-methyl -cis enantiomer, suggesting it is most like the actual product.

It can also be seen that, though the shifts of the (S,S) and (R,R) equatorial-methyl –cis enantiomers differ slightly, they are very similar, which is as expected. They should, in theory be exactly the same, and these results show clearly that the optimizations of the two structures were not perfect, and this again implies quantitative inaccuracies within the modeled structures.

However, interestingly, the spectra of the (S,S) axial-methyl conformer and two equatorial-methyl enantiomers differ substantially. Indeed, the spectra of the two equatorial-methyl enantiomers were more like that of the –trans isomer than the (S,S) axial-methyl conformer. Important and interesting results regarding the three of the spectra have been highlighted and discussed in the section following. (The results and spectra of the three products have been published and can be found at DOI:10042/to-992 (S,S)methyl-axial cis enatiomer; DOI:10042/to-1025 (S,S)methyl-equatorial cis enatiomer;DOI:10042/to-993 -trans isomer; DOI:10042/to-? UNABLE TO PUBLISH THE (R,R)-CIS ENANTIOMER RESULTS TO D-SPACE-SOMETHIG WRONG WITH THE NAME OR SOMETHING!!)

As the spectra of the two methyl-equatorial enantiomers should be the same, only one set of results needed to be used for analysis. The results used were of the (R,R) methyl-equatorial enantiomer. It would have been a lot more useful to have compared the (S,S) methyl-equatorial enantiomer because the methyl-axial conformer is also (S,S) but unfortunately earlier errors in assigning the structures meant the wrong enantiomer was done, and there was not time to make changes. All analysis on structure and position of atoms should still apply but please be aware that it is the (R,R) enantiomer used for comparison. Throughout the analysis the (S,S) methyl-axial conformer of the (S,S) methyl-equatorial enantiomer is described simply as the (S,S)-cis conformer, and the (R,R) methyl-equatorial enantiomer is described simply as the (R,R)-cis enantiomer.

.....(S,S)-cis conformer..................................-trans isomer..................................(R,R)-cis enantiomer

Figure 5 Atom-labelled images of the three compounds for the application in NMR peak assignment

An important difference between the spectra of the two –cis isomers and the –trans isomer is the shifts associated with carbons 3 and 9. In the two –cis isomers, the shift of carbon 3 is greater than that of carbon 9 (similarly with the product obtained from experiment), whereas in the –trans isomer, the shift of carbon 3 is less than that of carbon 9. This switch would be as expected because carbons 3 and 9 are those on either side of the bond undergoing change in the conversion from the –cis to –trans isomer. In the –cis isomers the methyl and hydroxyl group are both up (or down) relative to carbons 3 and 9, whereas in the –trans, the methyl is down and the hydroxyl up (or visa versa). This result provides very strong evidence for –cis stereochemistry present in the product obtained from experiment. One would perhaps expect greater differences for carbons 6 and 7, but comparison is difficult as carbon 6 is a part of a carbonyl group, whereas carbon 7 is not, and therefore, they are in very different environments.

However, the shifts of carbons 3 and 9 mentioned above and the shifts of carbon 4, discussed below, in the two –cis isomers are the only similarities between them. A rather unexpected result concerns the shifts caused by the methyl carbon, carbon 11, in each structure. In the (S,S)-cis conformer, it is almost exactly the same as the experimentally observed value, again strongly supporting (S,S)-cis conformer configuration of the product. However, the shift for the (R,R) enantiomer is much greater, and much more like that of the –trans isomer. Furthermore, analysis of the three NMR spectra show the shifts of carbon 7, 8 and 9 to be more alike between the (R,R)-cis enantiomer and –trans isomer than that of the (S,S)-cis conformer.

Possible reasons for these results become apparent on displaying the structures as shown below. It can be seen that the orientation of the five-membered ring relative to that of the six-membered ring is considerably more alike in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer and –trans isomer than in the (S,S)-cis conformer. Carbons 7,8 and 9 are all members of the five-membered ring, which further supports this explanation.

(S,S)-cis conformer...............-trans isomer...............(R,R)-cis enantiomer

Figure 6 Chemical environment of carbon 11 (and 7,8 and 9)

The other carbons of the five-membered ring, carbons 4 and 5, demand further analysis. The shifts of carbon 5, that holding the hydroxyl group, are almost the same in the (S,S)-cis conformer and –trans isomer, but different to that in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer; the shifts of carbon 4, that holding the methyl group, are the same in the two –cis isomers but different in the –trans isomer. It is very important to note here that the relative shifts of carbons 4 and 5 are the complete opposite to those of the actual product. The spectra of the modeled structures show the peak corresponding to carbon 5 to be shifted considerably further downfield than that of carbon 4. In the spectra of the experimentally obtained product, the opposite is seen. It may be, therefore, that there has been an error in the assignment of the shifts by either the published paper or the modeling system. In fact, the shifts seen in the CNMR of the modeled products would seem to make more sense. One would expect the very electronegative oxygen atom within the hydroxyl group to deshield the adjacent carbon (carbon 5), and shift it downfield.

A possible explanation for the results regarding carbon 4 (highlighted) in the three modeled structures can be reached on displaying the structures as shown below. The shift of carbon 4 is almost exactly the same in the two –cis isomers, (although the shift of the –trans isomer was more alike that of the actual product). It can be seen that in the –trans isomer the two carbonyl oxygen and hydroxyl oxygen are on one side of the molecule, ie. on the same side of carbon 4. This pulls electron density from carbon 4 all in the same direction. In the –cis isomers, as a result of the hydroxyl and methyl groups now being on the same side, one of the carbonyl oxygens is now angled, (to various degrees – much greater in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer), towards the other side of the molecule. In both cases, there is one oxygen atom on one side of carbon 4 and two on the other. This makes the chemical environment experienced by carbon 4 much more similar in the two –cis isomers than that in the trans.

(S,S)-cis conformer...............-trans isomer...............(R,R)-cis enantiomer

Figure 7 Chemical environment of carbon 4

As, the shift of carbon 4 was lower in the –trans isomer than the –cis isomers, it has been suggested that electronegative subsituents drawing electrons away from a nucleus in opposite directions results in greater deshielding than when it occurs all in the same direction.

In the case of carbon 5, the shifts are almost the same in the (S,S)-cis conformer and -trans isomer but different to that of the (R,R)-cis enantiomer. This may at first seem a little strange because one would expect the same effect described in the paragraph above to apply to carbon 5. Also, in the (S,S)-cis conformer carbon 5 has the hydroxyl group attached in the equatorial position, whereas in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer and –trans isomer, it is axial, which could be expected to affect the shifts. However, on displaying the structures as shown below, it can be seen that the hydroxyl oxygen and carbonyl oxygen of the six-membered ring in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer are pointing in similar directions (both axially downwards) but the hydroxyl oxygen and carbonyl oxygen of the five-membered ring are pointing in completely opposite directions (one pointing up, the other down).

In the (S,S)-cis conformer the five membered ring has twisted round resulting in the hydroxyl oxygen and carbonyl oxygen of the five-membered ring to be now pointing in almost the same direction (both up). This twist has also meant, however, that the hydroxyl group now points in the opposite direction to that of the carbonyl oxygen of the six membered ring, which would supposedly ‘cancel’ out the difference between the two structures. However, the hydroxyl group is now equatorial rather than axial and so the angle between the two oppositely directed oxygen atoms is not so great. The pictures show the three oxygen atoms in the (S,S)-cis conformer to be almost all on one side of carbon 5, more like the –trans isomer, than is seen in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer, where one oxygen is clearly on the other side of carbon 5 to the other two. The chemical environment of carbon 5 is, therefore, more similar in the (S,S)-cis conformer and –trans isomer than in the (R,R)-cis enantiomer.

(S,S)-cis conformer...............-trans isomer....................(R,R)-cis enantiomer

Figure 8 Chemical environment of carbon 5

In the case of carbons 2 and 6, there is the greatest similarity between the shifts of the (S,S)-cis conformer and –trans isomer, again presumably because of the respective directions of the three oxygen atoms.

One must conclude from this analysis, therefore, that CNMR is of limited effectiveness in this case: firstly, because of fairly considerable differences between all spectra - the modeled structures were not seemingly completely optimized and, therefore, inaccurate, and secondly, because the literature reported the spectra of two enantiomers but did not appear to specify which conformer was present making distinguishing between the two impossible. It may of course be, however, that the conformation is not specified because one of the conformers cannot actually form, the possible reasons for which have not been investigated and discovered due to time restrictions.

Table 1 Summary Table of CNMR Shifts

Proton NMR

A proton NMR was run for each of the three structures and a number of 3J coupling constants were determined using Janocchio. However, none of these would specifically help in indicating which isomer had been produced and analysed in experiment, and unfortunately coupling constants of the product obtained from experiment could not be found. Furthermore, the chemical shifts reported in two different papers differed quite considerably, making comparison difficult. It was, therefore, considered that the use of proton NMR was limited in its usefulness in confirming the stereochemistry of the product of the reaction and analysis was abandoned. The proton NMR spectra can also be found at the links given above.

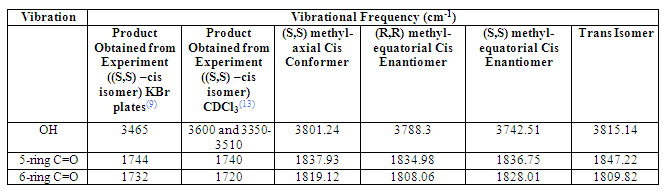

Infra-red

The infra-red spectra of the three modeled structures also proved to be unsuitable for structural analysis and gave no indication of which structure modeled is most similar to that of the product from experiment. All vibrations were considerably higher than those of the actual product and there was no obvious pattern to investigate and help confirm the stereochemistry of the product. It is thought such higher energy vibrations were observed because the three structures were not optimized to the extent present in the real product and these differences perhaps again highlight a limitation with the use of computer modeling as a highly accurate tool of research.

Table 2 Summary Table of IR vibrations

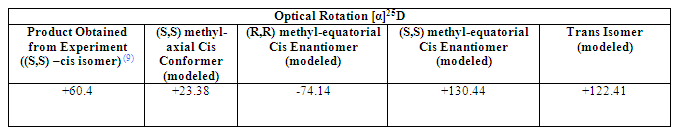

Optical Rotation

In this particular case, measurement of the optical rotation of the modeled structures and comparison with its value for the experimentally obtained structure should be perhaps the most useful and conclusive of all the analysis techniques. It is especially appropriate for the identification of the enantiomer present following the synthesis reaction.

Table 3 Table of Optical Rotations

However, the results, in fact, show a very confusing picture. Despite the difference in magnitude of the value, the sign of the result clearly shows and confirms it is an (S,S)-cis structure present in the reaction product. Furthermore, the value for the axial-methyl conformer is more alike that of the experimentally determined result than that of the equatorial-methyl group conformer, which can suggest it is indeed that conformer that is formed.

However, the value for the (R,R) equatorial-methyl -cis enantiomer should be exactly the same as the (S,S) form but with a different sign. There is indeed a sign change. However, they differ considerably in magnitude. In addition to this, the magnitude of the (R,R) equatorial-methyl enantiomer is the most similar to that of the experimentally obtained result of them all, which suggests it is the most optimized, accurate version of the product’s structure, but it is simply an enantiomer of it. However, it has its methyl equatorial and is therefore, supposedly, a different enantiomer and different ‘’’conformer’’’ of the obtained product. An exact enantiomer of the modeled (R,R)-cis structure would perhaps have given the best results with more accurate NMR data, more concurrent with that of the actual product, but this is not the product that is formed.

The optical rotation of the –trans isomer is also positive but twice the magnitude of the actual result, further implying its structure is very different to that of the product obtained in experiment.

It is, therefore, still very difficult to conclude anything from this data and clearly better optimisations and further structural analysis must be carried out before any decisions can be made.

Conclusion

The (S,S)-cis stereochemistry of the ketone intermediate (product in this paper) of the Hajos-Parrish-Eder-Sauer-Wiechert reaction has been confirmed by comparison of its chemical analysis with that predicted from modelled structures. It has been shown through cNMR and optical rotation predictions that the product obtained through experiment does not possess (R,R)-cis or -trans stereochemistry. Analysis of the modelled structures and the transition states involved in their formation have provided explanation for this selectivity and it has been shown the (S,S)-cis structure is the product of a kinetically-controlled reaction. However, no results from the modelling and optimisation of the structures have been obtained to allow verification of the ‘’’conformation’’’ of the (S,S)-cis product supposedly formed in experiment, and no firm conclusions have been made as to why one conformer is formed over the other. It is supposed that the energies of the transition states play a considerable part, though there is no evidence for this.

Furthermore, considerable differences between the modelled structure of the product supposedly formed in experiment and the actual experimentally obtained results highlight the limitations in accuracy associated with using computer modelling and optimisations. This is particularly the case because the starting geometry used to obtain the initial minimum has a considerable influence on the later optimisations used to obtain the final structure.

Predicted CNMR analysis appears to have shown considerable differences between the chemical environments of atoms in different conformations (axial/equatorial arranged substituents), especially when electron-withdrawing are contained within it. This conclusion, however, is again subject to inaccuracies in the modelled structures.

It has been very interesting investigating this reaction and the independent research opportunity it has provided has been greatly enjoyed.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, No. 4, 1991, (1335-1344)– Leo A. Paquette, Keith D. Combrink, Steven W. Elmore, Robin D. Rogers Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "taxolref1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tetrahedron Letters 21, No. 3, 1991, (319-332) – Steven W. Elmore and Leo A. Paquette

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 1990, (277-283) – Leo A. Paquette, Neil A Pegg, Dana Toops, George D. Maynard, Robin D. Rogers Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "taxolref3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ J. Org. Chem. 73, 2008, (6413-6416) – N.M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, P. Nguyen, D. Hansen

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 2, 1992, (447-450) – Brian Halton, Roland Boese, Henry S. Rzepa Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part2ref" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 PNAS. 101, No. 16, 2004, (5839-5842) – B. List, L. Hoang, H. Martin Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part3ref1" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 SYNTHESIS, Paper No. 9, 2005, (1533-1537) DOI: 10.1055/s-2005-865332– P. Cheong, K. N. Houk Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part3ref2" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 J. Org. Chem. 39, No. 12, 1974, (1615-1621) – Z. Hajos, D. Parrish Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part3ref3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Org. Biomol. Chem. (RSC), Paper No. 5, 2007, (3190-3200) – Stephen Davies, Angela Russell, Ruth Sheppard, Andrew Smith, James Thomson Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part3ref4" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Tetrahedron Letters 1965 (4719) – J. Elguero, R. Jaquier, G. Tarrago

- ↑ Tetrahedron 32, No. 3, 1976 – M. E. Jung

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 2001, (11273-11283) – S. Bahmanyar, K. N. Houk Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Part3ref7" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ J. Org. Chem. 39, No. 12, 1974, (1612-1615) – Z. Hajos, D. Parrish