Rep:Mod:Andy1235

Introduction Module

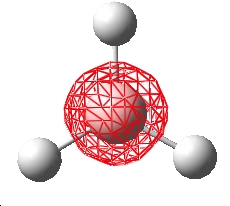

Creating the BH3 molecule

The molecule was drawn into Gaussview and the bond lengths changed to 1.50Å. The symmetry of the molecule was restricted to D3h

DFT optimisation of the BH3 molecule

The molecule was optimised using a DFT, B3LYP method and a 3-21G basis set. The resulting .chk file was retrieved and visualised in Gaussview.

Analysis of the BH3 molecule

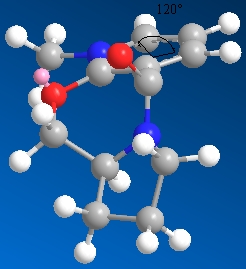

Geometry

B-H-B bond angle = 120°

B-H bond length = 1.19435Å

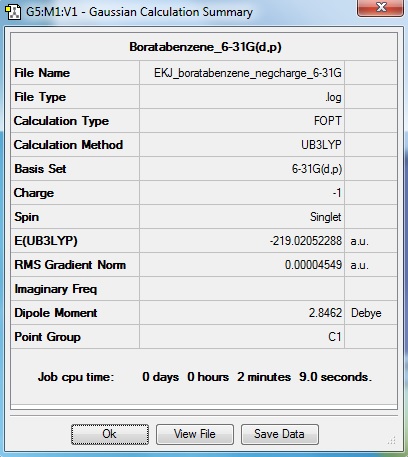

Summary information

Log information

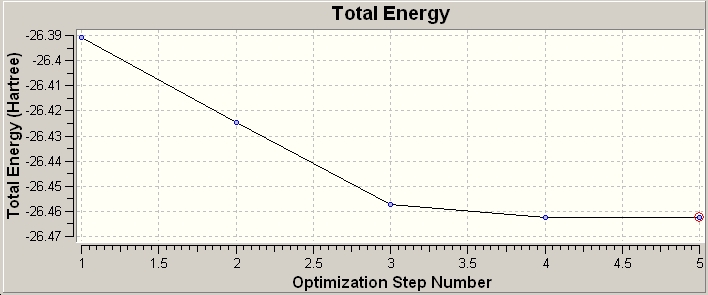

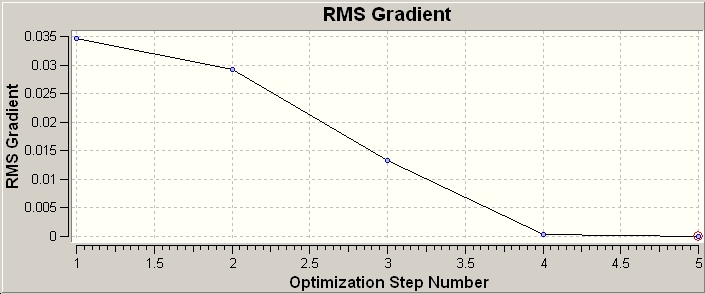

The log file was opened and the RMS and total energy graphs were created showing the energy and RMS (root mean square) at each optimisation cycle.

The steps of optimisation were observed (5 in total) from start to completion. At step 1 (shown below) there are no formal bonds shown, this is because gaussian defines "bonds" based upon distance parameter, clearly 1.5Ă is too far in this case for Gaussian to indicate the bond by connecting the atoms. On this note it should be noted that although it is easy to imagine bonds in the sense of the single, double, triple nature; this is a formalisation where a continuous spectrum of constructive electron density between 2 atoms is made discrete. Bonds are also descriptive of electron density between atoms, but when considered from a MO perspective they are areas of electron density within the MOs, this single etc description is a simplification from the MO view.

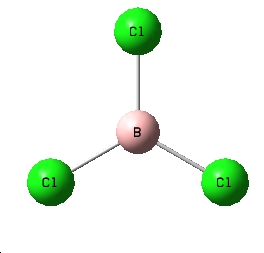

Pseudo-Potentials and Basis sets

A new molecule (BCl3) was drawn and its point group constrained to D3h. It was then submitted for calculation using a DFT method, B3YLP and a LanL2MB basis set. This basis set combination uses a D95V on first row atoms and Los Alamos ECP pseudo potential on heavier elements. This speeds up the calculation time whislt maintaining accuracy.

The commandline submitted to scan was "# opt b3lyp/lanl2mb", with the tital and cartesian coordinates of the atoms:

B -0.00000000 -0.00000000 0.00000000 Cl -1.61946750 0.93500000 -0.00000000 Cl 1.61946750 0.93500000 -0.00000000 Cl 0.00000000 -1.87000000 -0.00000000

After optimisation:

B-Cl bond length: 1.87Å

Cl-B-Cl angle: 120°

| Criteria | result |

| The file type | .log |

| The calculation type | FOPT |

| The calculation method | RB3LYP |

| The basis set | LanL2MB |

| The final energy in atomic units (au) | -69.43928112 |

| The dipole moment | 0.0000 Debye |

| The point group of your molecule | D3h |

| Time of calculation | 11.0seconds |

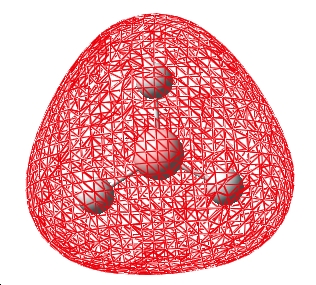

Analysis of NH3

Optimisation

The molecule was drawn into Gaussview , and optimised using the B3YLP method and a 3-21G basis set since there are no heavy atoms here.

"# opt b3ylp/3-21G" command line was used and the resulting .chk and .log files (on d-space at DOI:10042/to-1633 ) were retireived . The log file was opened and summary information investigated:

N-H bond length: 1.22Å

Vibration analysis

| Vibration | View | Frequency | Intensity | Symmetry | |||

| 1 |

|

1145 | 92.7 | A"2 [Wagging] | |||

| 2 |

|

1205 | 12.4 | E' [Scissor] | |||

| 3 |

|

1205 | 12.4 | E' [Rocking] | |||

| 4 |

|

2593 | 0.0 | A'1 [Symmetric stretch] | |||

| 5 |

|

2731 | 103.8 | E' [Asymmetric stretch] | |||

| 6 |

|

2731 | 103.8 | E' [Symmetric + Asymmetric stretches] |

Obviously there are 6 different stretching modes but only 5 on the spectrum , this is because the symmetric stretch (number 4) does not result in a overale change in dipole moment. For a vibration to appear in an IR, it must create an overall change in dipole moment and thus the symmetric stretch does not appear.

MO Analysis

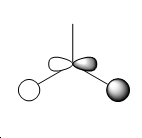

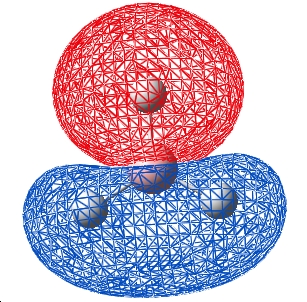

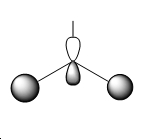

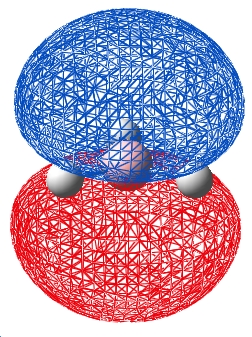

| Orbital | Visualisation | Qualitative |

| 1 |  |

|

| 2 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

| 4 |  |

|

| 5 |  |

|

The table above shows that the qualitative and quantitative MOs are in agreement for all the occupied and LUMO orbitals. The most significant difference is that the qualitative approach still localises orbitals to an atom, the MO shows a more "molecular" orbital in that the areas of electron density are not located at a specific atom. This said, the speed and fact that no computer or calculations are needed for the qualitative approach makes it fast and easy to apply, with results that are usefull.

TM Complex

This experiment focuses on the cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PMe3)2. Firstly the 2 isomers were drawn and optimised, in a 2 stage optimisation with increasing basis set size. Step 1 was a DFT calculation using the B3YLP method and a LAN2MB basis set/pseudo-potential, additionally because the normal convergence criteria for the calculation are more accurate (ie requires a lower gradient) than the method being employed can achieve the extra command "opt=loose" was added to relax the convergence criteria. 2 .gjf files were created using the command line "# opt b3lyp/lanl2mb opt=loose" along with the coordinates of each isomer. Step 2 used a higher basis set with the same method, the LAN2-DZ was used. Command line was "# opt b3lyp/lanl2mb int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" with the coordiantes from the optimised output of step 1. The additional commands instruct the convergence criteria to be set more tightly (possible due to the higher level basis set/pseudo-potential).

Pseudo potentials are useful in this experiment because we are dealing with atoms that have a (relatively) large number of electrons. To avoid long time-scale calculations we use basis sets along with pseudo-potential approximations. Since core electrons are bound tightly and therefore do not contribute to the reactivity, bonding, chemical nature of the atom as much as the valence electrons, they can be approximated. In terms of wavefunctions, all wavefunctions of the electrons in an atom must be orthogonal (not overlapping) thus as a valence electron wavefunction passes through the core electrons it oscillates to maintain orthogonality with the other wavefunctions at the core. As a result a complex wavefunction is needed to fully describe the valence electrons (to include all the oscillations), the pesudo-potential "smooths" the oscillations of the valence electrons as they pass through the core, whilst resmbeling the valence wavefunction very accurately outside of the core region.

The resulting logfiles were hosted on D-Space:

Cis:DOI:10042/to-1661

Trans:DOI:10042/to-1662

Following this a frequency calculation was performed on the optimised structures:

Cis:DOI:10042/to-1663

Trans:DOI:10042/to-1664

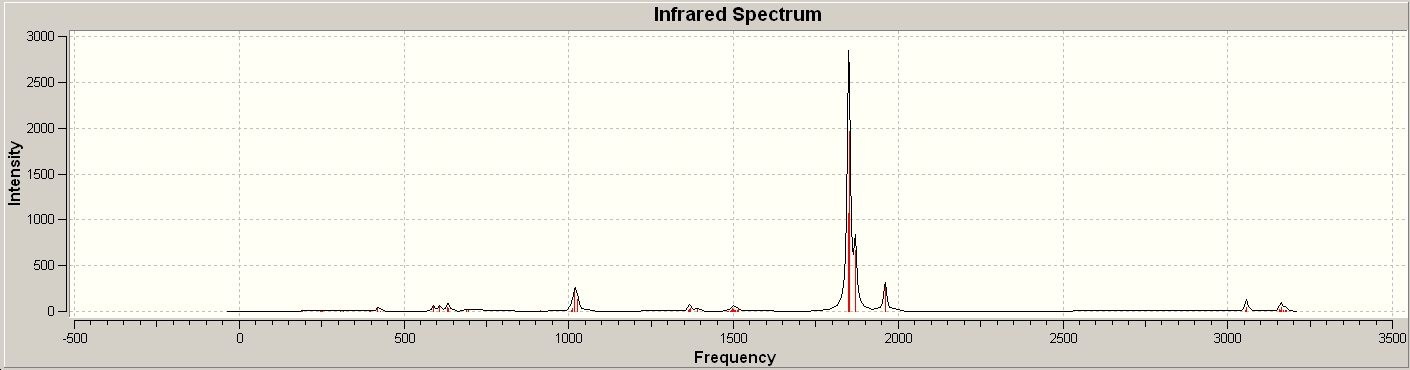

The C=O stretching frequencies were identified:

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

| 1848 | 1069 | |

| 1851 | 1961 | |

| 1870 | 666 | |

| 1960 | 322 |

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

| 1839 | 1998 | |

| 1839 | 2009 | |

| 1883 | 0 | |

| 1954 | 0 |

Addition of d-orbitals

Since phosphorus atoms have low lying d-orbitals that can interact with valent s and p orbitals, a more accurate calculation is one that takes this into account. Thus an extrabasis function was included which allowed for this in the calculation. The resulting optimisation led to slight changes in the calculated geometry and vibrations of the molecule.

Cis (d-orbitals):DOI:10042/to-1803

Trans (d-orbitals):DOI:10042/to-1802

Firstly the geometry differences can be assesed:

| ' | Cis | Cis (d-orbitals) | Cis (lit.[1]) | Trans | Trans (d-orbitals) | Trans (lit.[2]) |

| Average Mo - P bond length / Å | 2.65 | 2.63 | 2.52 | 2.57 | 2.55 | 2.50 |

| Average Mo - C bond length (Cis to P) / Å | 1.98 | 2.05 | 2.03 | 2.03 | 2.05 | 2.01 |

| Average Mo - C bond length (Trans to P) / Å | 1.98 | 2.00 | 1.97 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Average P - Mo - P angle / ° | 95.34 | 95.17 | 97.54 | 180.00 | 179.99 | 180.00 |

Overall accuracy of the calculation is good with an average error in bond lengths of 2.3% for the cis isomer and 1.96% for the trans isomer when not using d-orbitals on the phosphorus.

It is clear that when the d-orbitals are included in the calculation, the Mo - P bond length value gets better (0.75% and 0.78% improvement in the cis and trans isomer respectively) compared to the literature values. Unexpectedly, the Mo - C bond lengths and P - Mo - P angle values get worse compared to the calculation without d-orbitals on the phosphous.

This shows that both basis sets provide accurate geometry optimisations for both cis and trans isomers, whilst adding d-orbitals into the basis set improves the bonds which involve phosphorus.

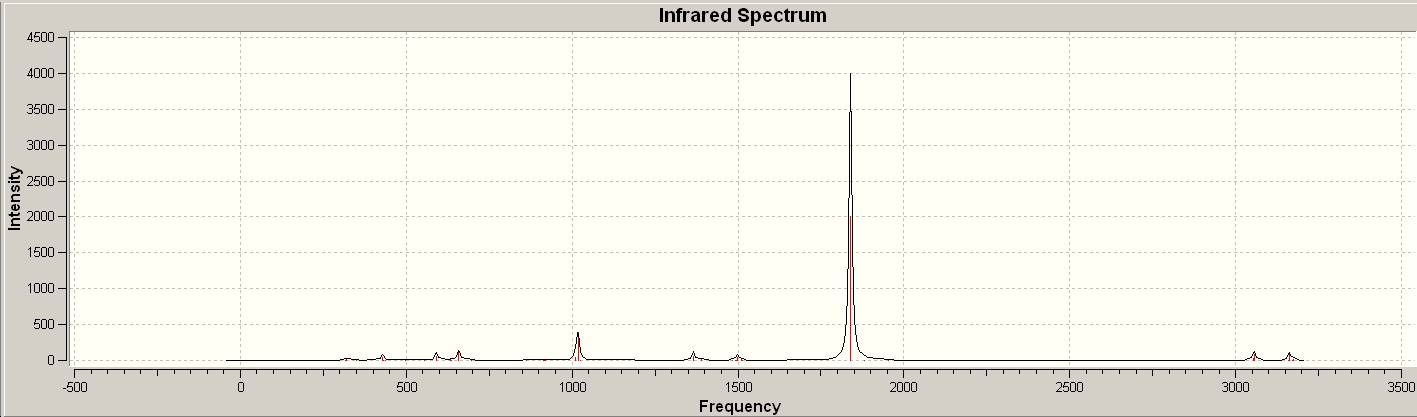

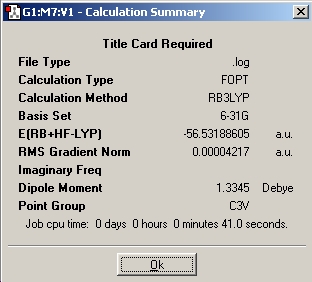

Ammonia

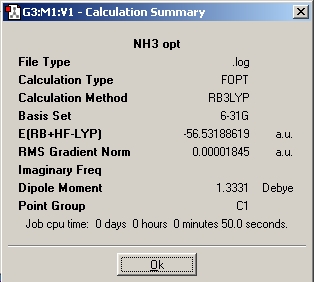

Initially the ammonia molecule was optimised using the B3YLP 6-31G method.

One bond was then lengthened and the optimisation re-run. The summary file is shown below, notice the C1 point group.

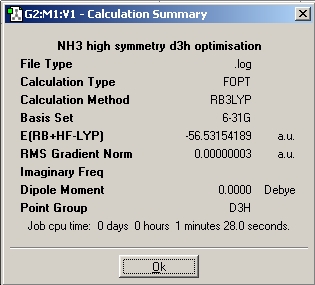

The molecule from the instruction website was then optimised, resulting in a planer molecule with D3h point group.

A consistent (6-31G) basis set was used throught the above calculations to make the results as comparable as possible.

The C1 ammonia molecule has a slightly lower energy than the C3V, probably due to the increased conformational freedom when no point group resstriction is placed on the molecule preventing some conformers being formed.

The highest symmetry D3h takes 28.0 seconds to run. The lower symmetry C3v took longer at 41.0 seconds and the lowest symmetry C1 ammonia took 50.0seconds to run. This is also evident in the RMS gradient graphs which show optimisation steps vs. energy. The D3h takes only 3 steps to fully optimise compared to the other two which took 7 steps each. The trend is that restricting the molecule to a higher symmetry reduces calculation time and the number of steps to optimise, for reasons given above.

The difference in energy between the highest and lowest energy conformers is E(D3h) - E(C1) = 0.0003443HF = 0.904KJmol-1. Thermal energy at 25°C = RT = 2.48KJmol-1, thus there is enough energy at room tmeperature to allow the molecule to achieve the D3h structure. This then allows the ammonia molecule to invert abount the N atom at room temperature.

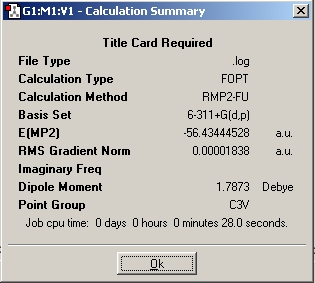

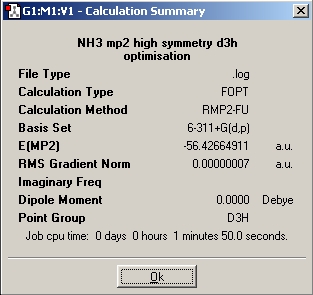

For a better indication of energy barriers, the molecule was optimised at a higher level (MP2) using a 6-311G+(d,p) basis set in both C3v and D3h conformations. The summary and molecule can be viewed below:

C3v

D3h

The energy difference was 0.00779617HF = 20.468kJmol-1, additionally the calculation times were about the same as the B3YLP method (starting from the B3YLP optimised structures). MP2 gets a far more accurate answer because it takes highly into account the dynamic correlation of electrons. The B3LYP method does take this into account but not as explicitly as the MP2 method. When comparing the 2 methods with experimentally determined values it is clear the MP2 method is MUCH more accurate.

B3YLP = 0.9KJmol-1

MP2 = 20.5KJmol-1

Experimental = 24.3KJmol-1

Clearly the MP2 method is much better, actually it has 84% accuracy compared to the B3YLP 3.7% accuracy against the experimental value. The importance of this difference in values is large when the MP2 energy is compared to the thermal energy at room temperature (2.48KJmol-1). The B3YLP method gave an energy of the D3h below the value of thermal energy avaliable, whereas the MP2 method energy is much higher than this value.

The mechanism of inversion can be thought of to take place by the movement of nitrogen from its position at the equilibrium configuration through the plane of the three hydrogen atoms. This model has already been proved unrealistic by analysing the energies involved. Since we know that ammonia does undergo inversion we can rationalise this via the boltzman distribution of energy throught the ammonia molecules. A small number of molecules in the "tail" of the distribution will have enough energy to overcome this barrier and thus invert. This rationale does not explain the much observed inversion thus another explanation must be thought about.

It is believed now that quantum tunnelling is responsible for the rapid inversion of ammonia at room temerature. This is non-classical and thus requires the problem to be treated quantum mechanically. Essentially this theory states that the classical activation energy does not have to be reached for the process to occur. Instead the electrons are able to tunnel through the barrier by overlap of the starting and final wavefunctions. This process is dependant on[3]

- Mass of Particles

- Height of Barrier

- Width of Barrier

- Dissipation

Intrinsically tunneling has no dependance on temerature, but infact the barrier width has some dependance on temperature and thus tunnelling becomes somewhat temerature dependant. This is because vibrations in the molecule can lead to the barrier width decreasing and thus increasing the rate of tunnelling.

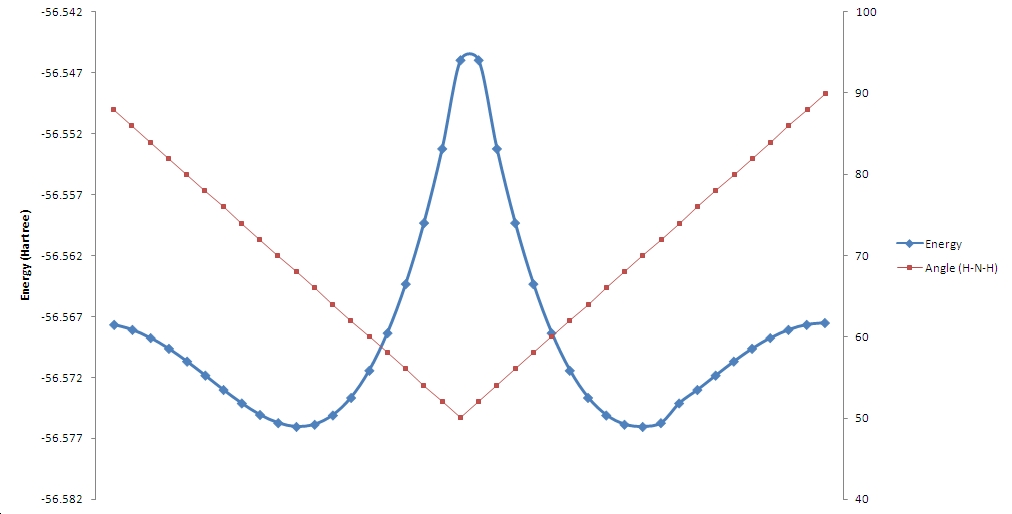

The potential energy surface of tunnelling of ammonia can be investigated using a scan technique, here one coordianted is moved and the others are optimised stepwise from the starting C3v structure to the intermediate D3h structure.

| scan | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| structure |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| scan | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| structure |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

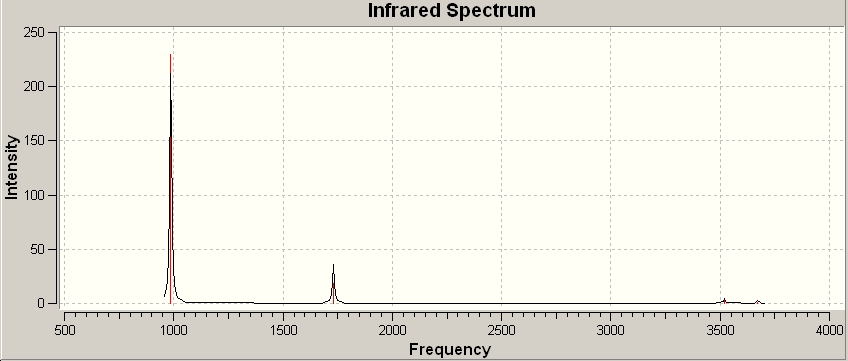

IR

C3V

| Number | Vibration | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry | Lit. Frequency[4] | |||

| 1 |

|

986 | 229.4 | A1 | 968 | |||

| 2 |

|

1731 | 18.1 | E | 1626 | |||

| 3 |

|

1731 | 18.1 | E | 1626 | |||

| 4 |

|

3521 | 4.6 | A1 | 3337 | |||

| 5 |

|

3671 | 1.3 | E | 3444 | |||

| 6 |

|

3671 | 1.3 | E | 3444 |

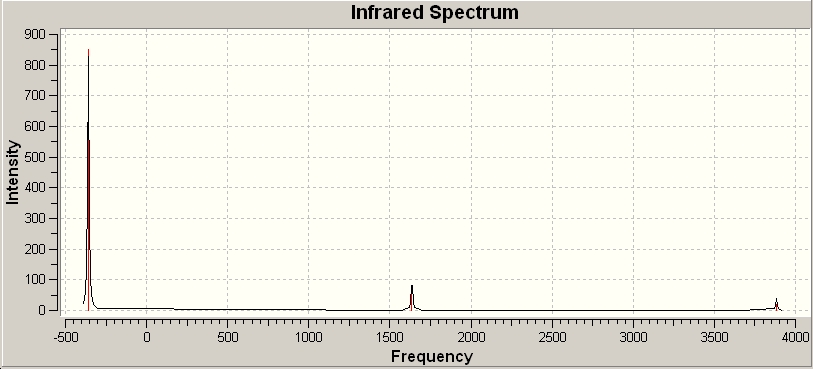

D3h

| Number | Vibration | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry | |||

| 1 |

|

-359 | 851.9 | A"2 | |||

| 2 |

|

1636 | 56.6 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

1636 | 56.6 | E' | |||

| 4 |

|

3663 | 0 | A'1 | |||

| 5 |

|

3883 | 19.9 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

3883 | 19.9 | E' |

The vibration 1 of the D3h vibrations follows the path of the inversion process. This is the negative frequency associated with the transition state. Vibration 1 in the C3V vibrations also follows the inversion path but is a positive frequency

Mini-Project

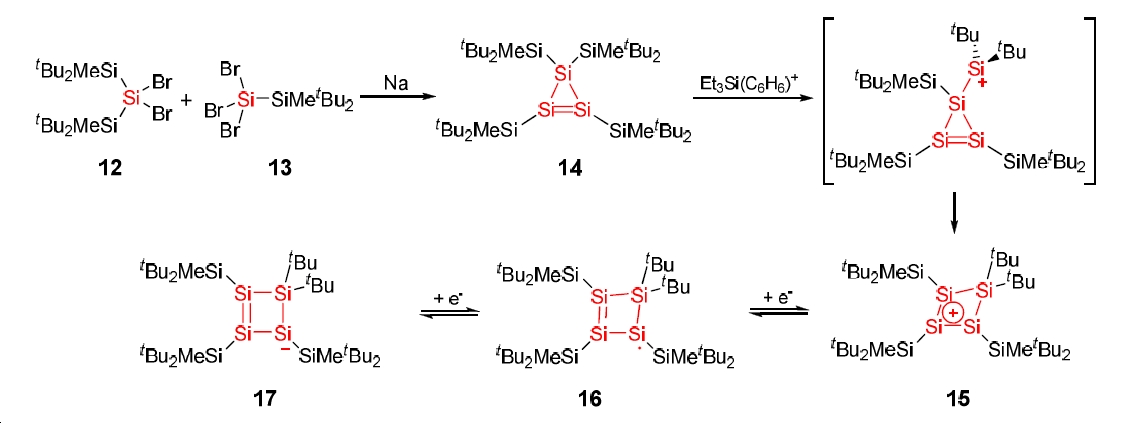

Introduction

Since the first preparation of the cyclopropenium cation by Breslow in the 1950s[5], the heavier analogues have been a target for synthesis. In 1999 Ichinohe et al[6] reported the synthesis of the silicon analogue, kinetically stabilised using the di(t-butyl)methylsilyl group. Interestingly when reacted with Et3Si(C6H6)+ a methyl abstracts to give the expected structure, which then (unexpectedly) undergoes electrophilic attack by the β-Silicon to the Si=Si double bond, reported by Sekiguchi et al in 2000[7]. The product is a cyclosilenium cation which is reported to posess homoaromaticity within the cyclic system. In addition, the cyclic product has been reported by Sekiguchi et al[8][9] in 2001/2002 to undergo reversible reduction from the cation, via the neutral radical through to the anion.

The aim of this project is thus:

- to model the expected and actual products of the methyl abstraction and compare their energies to determine which is more stable

- to explore and compare the MOs of the cation product and the reduced anion product, trying to identify any homoaromaticity/anit-homoaromaticity.

- to compare the computational results with published crystal structures to asses how accurately the computational method has modeled the molecules.

NB. Homoaromaticity is the phrase used to describe a system of overlapping p-orbitals but where 1 "π" bond does not have a σ bond between the associated atoms. For a further discussion of homoaromatic structures see the paper published by Winstein[10].

Methods

Due to the instability of these compounds, they are prepared with bulky substituents to provide kinetic stabilisation whilst retaining the same electronic character. t-butyl groups were used in this case which would have taken too long to run the higher level calculations. To avoid this the t-butyls were replaced with methyl groups. This should not alter the structure too much and will allow the calculations to run much faster.

To calculate the energies of the expected and actual products, the molecules were first optimsed via MM2 in ChemBio3D, these structures were then run using a Hartree-Fock method with STO-3G basis set, followed by a DFT method. The basis set used with the DFT method was a 6-31G + (d,p) because silicon has avaliable d orbitals that need to be accounted for, p orbitals were added to give more flexability to the optimisation. At DFT level the calculations took ~16h to complete on the scan server.

Results

Hartree-Fock optimisations

Expected product: DOI:10042/to-1816

Homoaromatic product: DOI:10042/to-1807

Reduced product: DOI:10042/to-1808

DFT optimisations

Expected product: DOI:10042/to-1837

Homoaromatic product: DOI:10042/to-1838

Reduced product: DOI:10042/to-1839

Discussion

Geometries

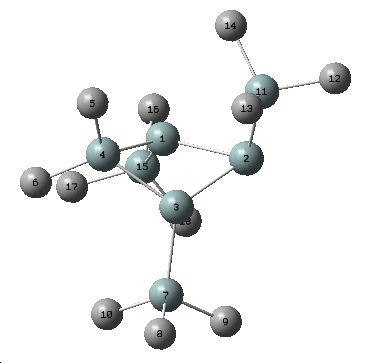

Overview

Firstly, the fully optimised structure for the expected 3 member ring product converged to the same geometry as the 4 member ring of the actual product. The starting positions of the atoms respectively was very different because they had formerly been run on MM2 were the 3 and 4 member ring geometries was forced. This immediately shows that the convergance gradient was enough to force the DFT calculation to create a 4 member ring. This is inline with the literature and the expected path of the reaction (the absense of a 3 member ring product experimentally).

To establish some idea of the scale of the energy difference, a basic MM2 calculation was run on the 2 isomers. The expected product had an energy of 84.8Kcal mol-1 versus the actual product with an energy of 8.12Kcal mol-1, a 90% difference. A comparison of the 2 DFT optimised structures, one starting from the 3 member ring and one from the 4 member ring, the 2 structures were almost exactly the same:

Comparison of DFT optimised structures starting from 3 and 4 member rings

| Interatomic measurement | 4 member starting product | 3 member starting product | Error (R2) | |

| Ring Distances | Si1-Si2 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 0 |

| Si2-Si3 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 0 | |

| Si3-Si4 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 0 | |

| Si4-Si1 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 0 | |

| Transannular | Si1-Si3 | 2.81 | 3.41 | 0.36 |

| Ring Angles | Si2-Si1-Si4 | 96.01 | 95.9 | 0.0121 |

| Si1-Si2-Si3 | 77.73 | 77.41 | 0.1024 |

Clearly this comparison shows that the geometries are very nearly the same, showing that the 4 member ring is much more stable than the 3 member isomer. In fact when the breakdown of the MM2 calculation was inspected, the 3 member ring was responsible for most of the destabilisation (121Kcal mol-1), further supported by the large decrease in bending strain in the 4 member ring (22Kcal mol-1).

The fully optimised structures were compared to cystallographic data from the literature to asses how well the geometries had been optimised:

Actual Homoaromatic Product

| Interatomic measurement | Crystal data[7] | Model | Error (R2) | |

| Ring Distances | Si1-Si2 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 0 |

| Si2-Si3 | 2.24 | 2.24 | 0 | |

| Si3-Si4 | 2.32 | 2.35 | 0.0009 | |

| Si4-Si1 | 2.33 | 2.35 | 0.0004 | |

| Transannular | Si1-Si3 | 2.69 | 2.81 | 0.0144 |

| Ring Angles | Si2-Si1-Si4 | 95.76 | 96.01 | 0.0625 |

| Si1-Si2-Si3 | 73.78 | 77.73 | 15.6025 |

Reduced Product

| Interatomic measurement | Crystal data[8] | Model | Error (R2) | |

| Ring Distances | Si1-Si2 | 2.22 | 2.38 | 0.0256 |

| Si2-Si3 | 2.32 | 2.38 | 0.0036 | |

| Si3-Si4 | 2.4 | 2.33 | 0.0049 | |

| Si4-Si1 | 2.4 | 2.33 | 0.0049 | |

| Transannular | Si1-Si3 | 3.32 | 2.53 | 0.6241 |

| Ring Angles | Si2-Si1-Si4 | 107.32 | 86.7 | 425.1844 |

| Si1-Si2-Si3 | 64.16 | 93.97 | 888.6361 |

On comparison, it is clear that the model has optimised the geometry to a conformer that is extremely similar to the observed crystal structures. An important point to note is because the molecules being investigated are charged the crystal structures obtained include a coordinated counter-ion, which will pertubate the structure to some extent. Even with this pertubation the fit between model and crystal structure is still very good. The model of the silyl cation is much better than the corresponding anion when compared to the crystal structures, the majoritory of disagreement being between the angles of the ring. The model skewwed the ring in the anion case much more than was suggested by the crystal structures, reasons for will be discussed later.

Comparison of the substituent orientations

| Cation | Anion | ||||

The ring systems in both products are very similar, with very little influence by the charge which is delocalised in the ring. In comparison the orientation of the substituents on the ring is very different. The cation has the substituents roughly in the plane of the ring whereas the anion substituents were almost othoganal to the ring, where only the charge has changed. This will be discussed after looking at the molecular orbitals.

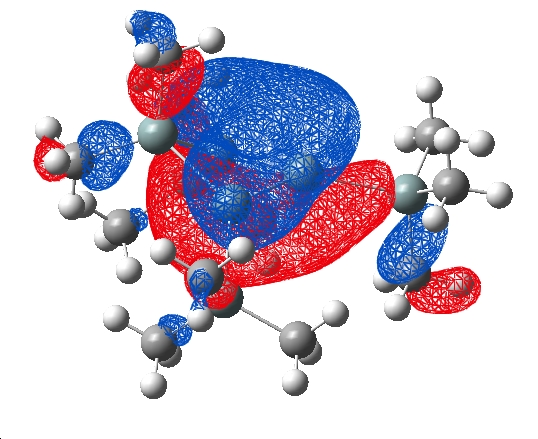

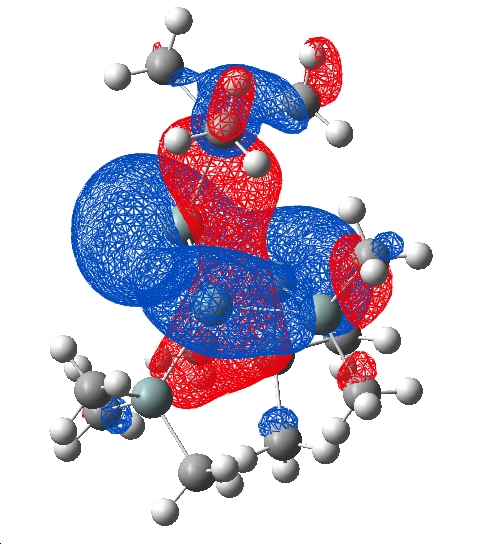

Molecular Orbitals

HOMO

| Cation | Anion |

|

|

The HOMO of the cation molecule shows a clear delocalised system across 3 Si atoms in the ring indicative of an aromatic orbital. With one phase above and the other below the plane of the ring (p-orbitals). This could be considered a homoaromatic orbital because it "skips" one of the ring silicon atoms. The anion does not show any such orbital suggesting that it does not posess this effect, this is concurent with the literature published by Sekiguchi et al. The 3 Si atoms covered by this orbital are in a plane and the relatively equal bond lengths reported previously further support the argument for homoaromaticity.

Following reduction to the anion the system will be formally anti-aromatic ie has 4n electrons. This is a high energy conformation and as a result the structure distorts to avoid this system. Thus a formally antiaromatic orbital was not observed with nodes between all atoms (in the HOMO or any other occupied orbital) and in fact a large distortion of the geometry was observed (see comparison to cyrstal structure). It was mentioned that the ring system did not change very much but the planarity of the substituents did, this can be attributed to the twisting of the atoms to break the anti aromaticity.

In this case electrons can be percieved to be localised in p-orbitals which have been twisted so that they do not overlap (in hybridisation terms the orbitals are given more p character), structuraly this means that the σ bonds formed which must be in the direction of the orbitals will resemble the new direction of the orbitals. This explanation rationalises the change in orientation of the substituents.

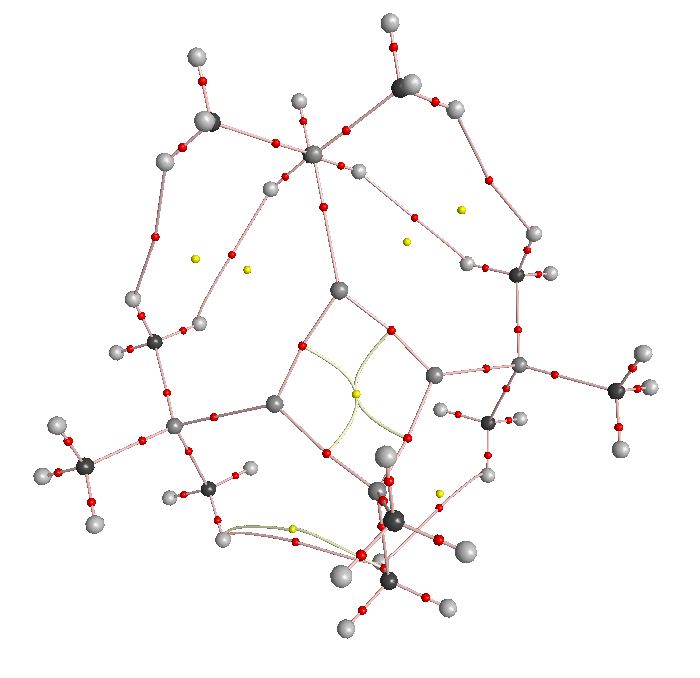

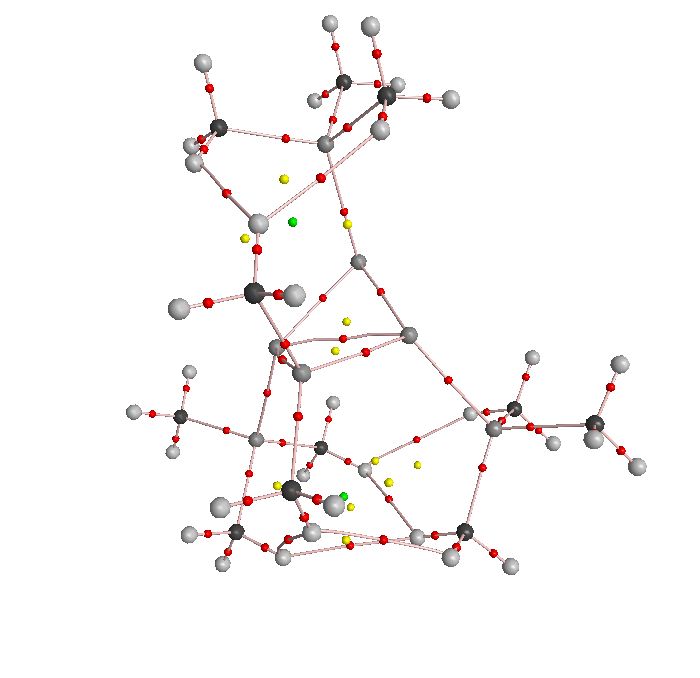

AIM Topology

Aromaticity is a complicated and complex phenomenon and thus although the basic "aromatic" orbital was identified in the cation, the exact details of the system are hard to decipher from this approach. As a result the structure was optimised at the B3YLP/6-31G+d,p level and set to give a .wfn output file,his can then be opened in AIM. It initially appears as a set of nuclear coordiantes with no bonds. In fact the file includes the "topology" of the electron density in the molecule (it includes the wavefunctions for all electrons across the molecule) parallel to "contours" on a map.

The program then applies a laplacian operator on the wavefunction (second derivative of the wavefunction with respect to the cartesian coordinates) and identifies areas of a positive curvature in all dimensions. These are what we formally describe as "bonds". Unlike previously where bonds are drawn as a function of distance, the AIM programe identifies characteristics of the wavefunction that resemble bonds. This is much more usefull when dealing with aromaticity, AIM also enables rings and even cages to be identified within a molecule:

- bond curvature point - red dot

- ring curvature point - yellow dot

- cage curvature point - green dot

AIM was run on the cation and anion optimised structures:

| Cation | Anion |

|

|

First to note is the complexity of the output, this project is only going to consider the silicon ring system due to time constraints. The cation is in a "top-down" view and the anion is from a perspective angle.

The cation provided some interesting results in that the yellow point (ring) is in the centre of all 4 silicon atoms, this is odd because one would expect 2 3 member rings (1 aromatic and the other not in this case) the result is actually a result of the calculation. It is noted in a paper C. Allen and H. Rzepa[11] that "subtle variations in the local electron density induced by local or remote substituents, and which can in turn induce self-annihilation or creation of a pair of bond and ring critical points". This has happened here where 2 rings were formed proximal to a bond critical point across the ring, followed by annihilation of one ring point and the bond point to give the 4 membered ring. Working this back shows that there was a bond critical point across the ring which is further evidence for the homoaromatic system in the cation.

The cation shows the 2 clearly defined ring systems, interestingly with a bond critical point across the ring suggesting that the molecule distorted from its structure but maintained some interaction across the ring. When looking at the HOMO of the anion, the red phase of this orbital actaully joins the 2 atoms in question in the AIM analysis which supports the speculation that there is some bonding interaction between the 2 silicon atoms. The ring is also clearly less planer than the cation ring - indicative of the distortion in the molecule. The distance in the anion from silicons mentioned previously is actually shorter than in the cation. This also goes against the prediction that a homoaromatic system would cause the transannular distance to decrease. This is intuitively the obvious answer but the distortion of the anion and presence of a bonding MO across the distance has actually a larger effect on the transannualr distance.

From this calculation it can be concluded with support from looking at the MO's that there is indeed a homoaromatic system in the cation (although not immediately clear from the AIM calculation, it acctually occurs). Further to this the reduced product anion that was predicted to be anti aromatic has distorted geometry to evidently maintain a bonding interaction across the ring and avoid the destabilisation of antiaromaticity. After reading papers concentrating on computational treatment of homoaromaticity, it was decided that another interesting calculation to run would be an ELF calculation[12] This integrates the electron density across the critical points to determine the number of electrons in that particular "bond". This was run and the result visualisation of the cation can be viewed here:

ELF calculation results[1]

The surfaces represent "synaptic basins" which indicated some electron density associated with a bond. Interestingly there is no such basin in the transannualr bond which indicates no homoaromatic elecment to the structure. This contradicts the previous 2 calculations which confirmed some type of electron density between these two silicon atoms, since C Allen and H Rzepa "suggest that the ELF and ELFπ thresholds for any basin found in the homoregion are better indicators of the delocalized nature of the homoaromatic interaction and the aromaticity of the system" it throws into doubt the presence of any homoaromatic system.

Conclusion

In conclusion to this project, the lower level calculations (MO's and AIM) suggest that the cation product has a homoaromatic element but this has been contradicted by ELF calculations which have been given some weight by published literature[12][11] this leads to the requiremen for further investigation into the exact electron system present. Geometry (bond lengths) suggest a homoaromatic system due to their relitively consistent value, but this could be down to several factors and not specifically homoaromaticity. It is worth noting the large change in structure of the reduced product, which can be rationalised by the twisting out of an antiaromatic system. This would require that the homoaromaticity was present and thus enables a anti aromatic system. Further investigation is needed to find out if a homoaromatic system is in fact present in the cation. From the evidence collected so far including crystal structures and computational results one can tentively predict that a homoaromatic system is actually present.

References

- ↑ G. Hogarth, lnorganica Chimica Acta, 254,1997, 167-171 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ F. Cotton, Inorg. Chem. 1982, 21, 2661-2666

- ↑ DULAL C. GHOSH, JIBANANANDA JANA, RAKA BISWAS.,Quantum Chemical Study of the Umbrella Inversion of the Ammonia Molecule

- ↑ D.Dixon, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2005, 109, 5129-5135

- ↑ R. Breslow, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1957, 79, 5318

- ↑ M. Ichinohe, T. Matsuno, A. Sekiguchi, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2194

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Sekiguchi, T. Matsuno, M. Ichinohe, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11250

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 A. Sekiguchi, T. Matsuno, M. Ichinohe, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12436

- ↑ A. Sekiguchi, T. Matsuno, M. Ichinohe, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1575

- ↑ S. Winstein J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1959; 81(24); 6524-6525

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Charlotte S. M. Allan and Henry S. Rzepa, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 1841–1848

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Charlotte S. M. Allan, Henry S. Rzepa., J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6615–6622