Rep:Mod:Ab mod1

Modeling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

4πs+ 2πs cycloaddition of Cyclopentadiene can form two product, endo or exo, however this process is mainly endo selective. This was determined by using MM2 force field to minimise the molecules energies. The data for which can be seen below.

Endo or Exo selectivity

| ' | Exo (1) | Endo (2) |

| Stretch: | 1.2504 | 1.2855 |

| Bend: | 20.8466 | 20.5794 |

| Stretch-Bend: | -0.836 | -0.8382 |

| Torsion: | 9.5115 | 7.6571 |

| Non 1,4 VDW: | -1.5443 | -1.4171 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 4.3216 | 4.2322 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | 0.4477 | 0.3776 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol): | 31.8766 | 33.9975 |

The Kinetic product[1] is the product which forms the quickest as it has a lower activation energy, whereas the Thermodynamic product is the most stable product and therefore has the lowest total energy. From the above table it can be deduced that the Exo product is thermodynamically favored as it's energy is lower by 2.1209 kcal/mol, and thus more the more stable product. The reason the Endo product has a higher total energy is due to the 1,4- torsional strain seen in 'Figure 1' below.

At lower temperatures, the endo product would be predominately formed as it is kinetically favoured[2] and thus easier to form, however the product is not as stable as the exo product. As you increase the temperature the exo product can be forced as it has enough energy to overcome the activation barrier. The cyclodimerisation of cyclopentadiene forms the endo product specifically thus showing that the reaction is kinetically controlled.

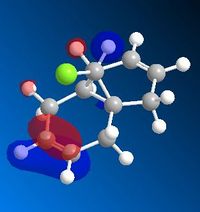

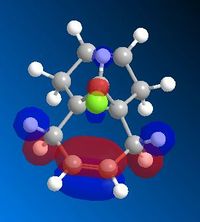

Frontier molecular orbitals can be used to support this observation:

From the above it can be seen that the Endo transition state has addition stabilisation of the HOMO and LUMO which can not be seen in the exo transition state, therefore this additional supports the idea that the endo product is the kinetic product.

Hydrogenation of Endo Dimer

The dimer can be hydrogenated to produce two different products (3 and 4), further hydrogenation will completely reduce both double bonds[3]. MM2 calculations were carried out on both products as above and from this we can deduce which product is thermodynamically favoured.

| ' | Product 3 | Product 4 |

| Stretch: | 1.2773 | 1.0965 |

| Bend: | 19.8582 | 14.5247 |

| Stretch-Bend: | -0.8345 | -0.5488 |

| Torsion: | 10.8115 | 12.4989 |

| Non-1,4 VDW: | -1.223 | -1.0708 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 5.6334 | 4.511 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | 0.1621 | 0.1406 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol): | 35.685 | 31.1522 |

Product 4 has a lower total energy by about 4.5328 kcal/mol, therefore it can be deduced that is it the thermodynamic product. This results from the fact that the additional bridging distorts the sp2 from the ideal angle of 120o. The angle is distorted to 108o on one side and 112o on the other side (see image below). Thus this reduction in bond angle favours the formation of product 4 over product 3.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Products 9 and 10 are used in the synthesis of Taxol and when left to stand they can isomerise to form the other product via the Oxy-Cope Rearrangement[4]. There are also different arrangements of these products depending on the conformation of the ring (chair or twist boat).

| ' | 9- Chair | 9- Twist Boat | 10- Chair | 10- Twist Boat |

| MM2 (kcal/mol) | 44.2887 | 53.01 | 39.6021 | 46.4337 |

| MMFF94 (kcal/mol) | 63.2884 | 78.0072 | 47.6712 | 66.302 |

Both MM2 and MMFF94 calculations were carried out, and although the values are different (due to the use of different parameters) they both follow the same trend and show that the chair conformation is more stable than the twist boat. The twist boat is more stable than the boat conformation as it is able to reduce some of the torsional strain in the ring but still maintains some some of the strain characteristic to the boat conformation.

The above table also shows that Product 10 is thermodynamically favoured over product 9. Product 9 thus may be the kinetic product which is initially formed then converted to product 10 once left to stand or when heated.

| ' | 9- Chair | 9- Twist Boat | 10- Chair | 10- Twist Boat | 10- Boat |

| Stretch: | 2.6365 | 2.8762 | 1.8832 | 2.7103 | 5.6087 |

| Bend: | 12.5533 | 17.2786 | 9.5085 | 11.7413 | 87.1488 |

| Stretch-Bend: | 0.4246 | 0.4725 | 0.3843 | 0.3237 | 0.0623 |

| Torsion: | 19.1198 | 20.6085 | 19.2716 | 21.8612 | 21.8728 |

| Non-1,4 VDW: | -1.6061 | -0.8938 | -2.683 | -2.0911 | 0.8496 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 12.8622 | 14.3764 | 12.9945 | 13.9201 | 26.8967 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | -1.7016 | -1.7085 | -1.7571 | -2.0319 | -2.8618 |

The MM2 values for the Boat conformation of Product 10 were calculated, however when using MMFF94 the conformation changed to that of a Twist Boat. Thus, it was concluded that the Boat conformation is highly unfavorable as it had a total energy of 139.5771 kcal/mol, which is significantly higher than Chair and Twist Boat. This is due to the eclipsing of the carbons and the flagpole hydrogens.

These alkenes are particularly stable towards hydrogenation because they are additionally stabilised by the bridge and have an angle of 124o which is close to the optimum 120o angle for sp2 hybridised carbons.

Hydrogenation of this alkene will result in an increase in repulsive Van der Waals interactions within the molecule. Repulsive Van der Waals interactions occur when the distance between two hydrogen's is closer than the sum of their Van der Waals radii. The Van der Waals radius for hydrogen is 1.2Å therefore the sum of their radii would be 2.4Å. The image below shows that the distance between the two hydrogen's are shorter than the Van der Waals radii, thus resulting in repulsion which is not favoured.

The total energy of the hydrogenated product (calculated using MM2) is 62.0793 kcal/mol which is significantly higher than that of the alkene (see table above).

Modeling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Chlorocarbenes are susceptible to electrophilic attack because they have an electron deficient nature.

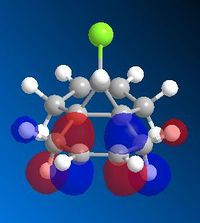

The HOMO below shows that the alkene endo to the chlorine is the most reactive end towards electrophilic attack. Majority of the electron density rests on the endo alkene and thus proves the selectivity of the reaction.

Part 1: Orbital Control

MM2 minimisation was used to optimise the geometry of the molecule. Then Mopac-PM6 was used to create the Molecular orbitals, however as seen above the molecular orbitals are not symmetrical therefore Mopac-RM1 method was a more appropriate method to produce a symmetrical set of orbitals. The molecule has Cs symmetry therefore the molecular orbitals should display Cs symmetry as well.

The exo double bond can be seen in the LUMO+1 and less nuceleophilic due to the overlap between the highly filled pi orbitals and the low lying empty C-Cl σ* orbital which energetically stabilises the bond and makes it less favourable to attack.

Part 2: Vibrational Frequencies

| (cm-1) | Compound 12 | Compound 13 |

| C-Cl | 819.4 | 838.585 |

| C=C (endo) | 1756.41 | 1772.12 |

| C=C (exo) | 1758.97 | - |

From the table above it is evident that there is a shift in the IR frequencies. Compound 12 has a lower C-Cl frequency than compound 13 because of the electron donation from the exo π orbital into the σ* orbital of the C-Cl. The exo double bond is present in 12 but not in 13 therefore resulting in a shift in frequency. The C-Cl bond is therefore stronger in 13 than in 12 because the removal of the exo bond means that there is no π orbital interaction into the antibonding σ* of the C-Cl bond. Compound 13 shows no value for the exo double bond as it is no longer present. The increase in the number of hydrogens leads to an increase in vibrational modes and thus an increase in the number of peaks.

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

Glycosidation of D-glucose can be carried out by substituting a leaving group on the anomeric centre with a nucleophile. However this will lead to a mixture of α- and β- anomers. However a method for controlling this is the addition of an ester group which will lead to selective substitution through neighboring group participation, the carbonyl group can stabilise the oxonium ion and therefore block off one face, thus making sure the nucleophile attacks from the opposite face to produce a single anomer as seen below.

MM2 and Mopac PM6 methods were used to minimise their energies and the R group was substituted with a methyl group to make the calculations more manageable. MM2 and Mopac differ because MM2 considers force constants whereas Mopac does not, however Mopac does consider the electronic effects and the change in charge distribution therefore for these molecules Mopac is a more accurate method to use as the charge on the oxygen moves from A to C and B to D. It was found that around molecule had it's own isomer which was found when ring flipping was carried out to give A', B', C', D'.

| ' | A | A' | B | B' |

| Stretch: | 2.4949 | 2.493 | 2.325 | 2.6202 |

| Bend: | 14.4178 | 14.4168 | 14.7812 | 16.6254 |

| Stretch-Bend: | 1.0005 | 0.9999 | 0.9315 | 1.0183 |

| Torsion: | 4.149 | 4.1464 | -0.2708 | -0.1513 |

| Non-1,4 VDW: | -2.3297 | -2.3345 | -0.7111 | -0.9965 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 20.1252 | 20.1241 | 19.3764 | 18.0576 |

| Charge/ Dipole: | -15.5775 | -15.5811 | -17.1754 | -10.4909 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | 9.2633 | 9.278 | 8.1394 | 8.2456 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol): | 33.5434 | 33.5427 | 27.3962 | 34.9285 |

| Mopac (PM6) | ||||

| Heat of Formation (kcal/mol): | -66.33587 | -75.9074 | -68.23434 | -68.23374 |

From the above table it can be deduced that A has a lower total energy than B and therefore more stable. Also their isomers A' and B' were higher in energy and thus not as stable because the carbonyl is now out of plane and is no longer able to stabilise the oxonium ion.

| ' | C | C' | D | D' |

| Stretch: | 1.7767 | 1.9621 | 2.0148 | 1.8418 |

| Bend: | 15.5975 | 12.8231 | 16.014 | 18.9939 |

| Stretch-Bend: | 0.6752 | 0.7296 | 0.9444 | 0.8064 |

| Torsion: | 7.3185 | 10.341 | 9.7194 | 8.3949 |

| Non-1,4 VDW: | -4.4319 | -4.0246 | -3.8932 | -3.6157 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 17.559 | 18.1677 | 17.1498 | 17.0181 |

| Charge/ Dipole: | -2.2563 | -3.4548 | 2.9337 | -3.9218 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | -0.6175 | -2.5397 | -1.7771 | -1.7443 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol): | 35.6213 | 34.0045 | 43.1058 | 37.7734 |

| Mopac (PM6) | ||||

| Heat of Formation (kcal/mol): | -91.64394 | -91.65994 | -81.92291 | -88.53823 |

The above table shows that C is more stable than D due to the fact that the carbonyl group is able to stabilise the oxonium ion. This is due to the anomeric effect which states that subsitutents adjacent to heteroatoms prefer the axial position instead of the equatorial position that is usually preferred when considering steric requirements within a molecule. The C-O σ* orbital is able to interact with the oxygen lone pair when in the axial position and no interaction is seen when in the equatorial position.

The nucleophile is only able to attack at the Burgi-Dunitz angle of 105°[5], therefore limiting the attack to trans to the acyl group and leading to further selectivity on the anomer produced.

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular Orbital Methods

Intramolecular Ketene- Allene Cycloadditions

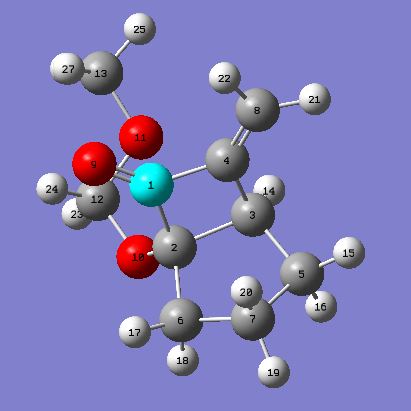

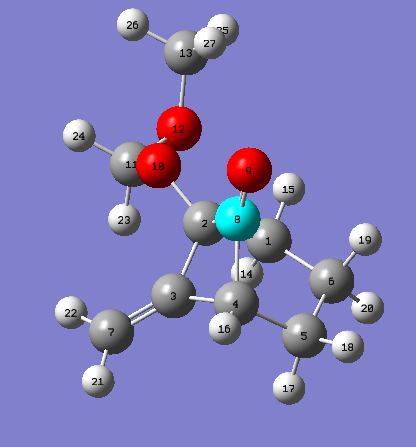

Kristen L. McCaleb and Randall L. Halcomb et al.[6] discovered that the intramolecular [2+2] cycloaddition of ketenes and allenes can form two different products depending on the conformation of the molecule when it attacks itself. Bonds can either form between the central ketene and the central allene to give the fused bicyclic system (15c) or a between the alkoxy-substituted carbon and the central allene carbon to give a six-membered ring with a bridging carbonyl group (16c). The preference over which product is formed depends on the reaction conditions. The calculations carried out below will support the evidence of the formation of the two products.

These two products cannot be differentiated by IR as both compounds contain the same functional groups; however 13C NMR can be used to differentiate the structures.

Product 15c: 15c Project 16c: 16c

MM2 and Mopac PM6 calculations were carried out on both products to produce the following data:

| ' | 15c | 16c |

| Stretch: | 2.1986 | 1.5007 |

| Bend: | 38.0584 | 38.7324 |

| Stretch-Bend: | -0.9409 | -0.4518 |

| Torsion: | 10.1837 | 7.4487 |

| Non-1,4 VDW: | -3.673 | -2.8653 |

| 1,4 VDW: | 8.8652 | 10.374 |

| Dipole/ Dipole: | 1.9814 | 2.8009 |

| Total Energy (kcal/mol): | 56.6734 | 57.5396 |

| Mopac (kcal/mol) | ||

| Heat of Formation: | -95.10592 | -88.03636 |

Intramolecular thermal [2 +2] cycloaddition forms 7-methyldinebicyclo[3.2.0]heptanones (15c) and 7-methyldinebicyclo[3.1.1]heptanones (16c) in the ratio of 5:1. From the above results it can be seen that 15c is slightly lower in energy thus favoring the formation of 15c over 16c. The 5:1 ratio may be seen because 15c is the thermodynamic product therefore as the reaction is heated to 65°C the thermodynamic product will predominately form. If the temperature was lower then more of the kinetic product (16c) may be seen. This reaction has a higher selectivity than if the R groups on the alkene were n-Bu or TMS. Had there been more time a further investigation could have been carried out to investigate the energies of these molecules when you change the R substituent.

Carbon NMR Spectrum

Comparison of literature and calculated NMR values for compound 15c

| Carbon No. | Literature | Calculated | Difference |

| 1 | 203.4 | 196.8 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 102.3 | 98.7 | 3.6 |

| 3 | 48 | 48 | |

| 4 | 154.9 | 151.4 | 3.5 |

| 5 | 34 | 34.5 | 0.5 |

| 6 | 36.5 | 37.7 | 1.2 |

| 7 | 24.4 | 25.4 | 1 |

| 8 | 116.1 | 115.6 | 0.5 |

| 12 | 94.6 | 91.9 | 2.7 |

| 13 | 56.5 | 51.6 | 4.9 |

As seen from the table above there is a good agreement between the calculated NMR shifts and the literature values. This shows that the optimized geometry for the compound was carried out successfully and the arrangement of the molecule achieved is actually the arrangement which is formed. The below bar chart shows a visual representation of the difference between the literature and calculated NMR values. Little difference is seen thus there is good agreement between calculated and literature NMR values. There is no calculated NMR value for carbon 3, this could be due to symmetry factors.

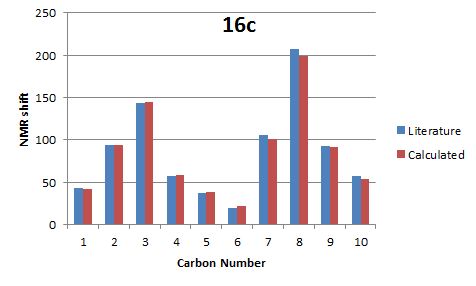

Comparison of literature and calculated NMR data for 16c

| Carbon No. | Literature | Calculated | Difference |

| 1 | 43 | 41.7 | 1.3 |

| 2 | 93.8 | 93.4 | 0.4 |

| 3 | 143.5 | 144.3 | 0.8 |

| 4 | 57.2 | 58.3 | 1.1 |

| 5 | 36.8 | 37.7 | 0.9 |

| 6 | 19.3 | 21.3 | 2 |

| 7 | 105.1 | 101.1 | 4 |

| 8 | 206.7 | 198.8 | 7.9 |

| 11 | 92.6 | 90.8 | 1.8 |

| 13 | 56.8 | 53.2 | 3.6 |

From the tables above it can be seen that the calculated data closely resembles the NMR data given in the literature. This shows that the geometry of the two products calculated matches the actual geometry of the product.

J Coupling

Three bond J couplings can be easily calculated using Janocchio , in which the J values between selected hyrogens can be calculated and thus compared to other J values in the molecule. Below is a table showing the J couplings calculated from this program.The J coupling values above show which hydrogen's couple together. Those with the same J value, couple with each other.

J coupling values for 15c

| ' | Angle | J |

| Ha-Hc | -35.3 | 6.96 |

| Ha-Hb | 84.7 | 0.96 |

| Hb-Hd | 41.7 | 6.31 |

| Hb-He | -78.5 | 0.93 |

| Hc-Hd | 162.5 | 12.10 |

| Hc-He | 42.3 | 6.20 |

| Hd-Hf | -41.5 | 6.36 |

| Hd-Hg | -162 | 12.04 |

| He-Hf | 78.9 | 0.91 |

| He-Hg | -41.7 | 6.31 |

The above table shows us that Hb-Hd and He-Hg has similar J coupling values, this may be because they are both coupling with something in the same phase as itself. Hc-Hd and Hd-Hg have large and similar J values due to the fact they are coupling with something (3 bonds apart) in the opposite phase as itself.

J coupling values for 16c

| ' | Angle | J |

| Ha-Hb | 76.6 | 1.26 |

| Ha-Hc | -40.8 | 6.06 |

| Hb-Hd | -38.1 | 6.96 |

| Hb-He | -153.3 | 10.85 |

| Hc-Hd | 80 | 0.86 |

| Hc-He | -35.1 | 7.49 |

| Hd-Hf | 35.9 | 7.36 |

| Hd-Hg | -82.1 | 0.79 |

| He-Hf | 151.2 | 10.50 |

| He-Hg | 33.2 | 7.83 |

The most interesting observation deduced from the table above is the values of the J couplings for the hydrogen's which are antiperiplanar to each other: Hb-He and He-Hf. These show large and similar J coupling values due to the fact they have a 180° dihedral angle. When the dihedral angle approaches that of a gauche orientation the J value decreases, i.e. when comparing Hb-He (180°) J coupling value of 10.85 to that of Hc-He (60°) at 7.49. This is related to the Karplus equation: ³J(Φ)= Acos²(Φ)+Bcos(Φ)+C [7] and the Karplus curve.

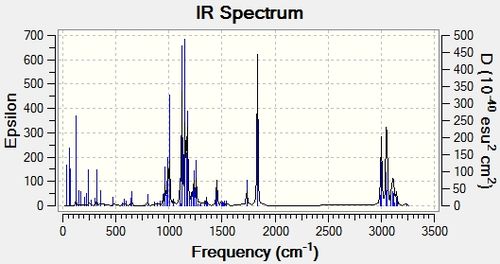

IR Spectrum

Literature and calculated IR values for 15c

| Functional Group | Literature | Calculated |

| C=O | 1759 | 1834 |

| C=C | 1654 | 1733 |

| C-O | - | 1122 |

The values do not agree as well as the NMR data does but it is evident that the functional groups peaks that need to be present are present. The peaks were assigned to their relevant bonds using gaussview which allows you to see the vibration of that particular bond. This was the most accurate method for assigning the bonds.

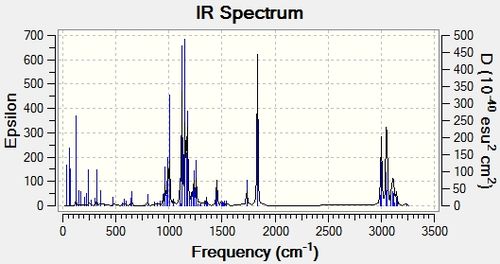

Literature and calculated IR values for 16c

| Functional Group | Literature | Calculated |

| C=O | 1794 | 1893 |

| C=C | 1685 | 1760 |

| C-O | - | 1043 |

References

- ↑ J. Clayden, N. Greeves, S.Warren and P. Wothers, Organic Chemistry, 2001, 328-331,

- ↑ Branko S. Jursic, A Density Functional Theory Study of Secondary Orbital Overlap in Endo Cycloaddition Reactions. An Example of a Diels-Alder Reaction between Butadiene and Cyclopropene, 1996, 3046-3048, DOI:10.1021/jo9620223

- ↑ David Skala, Jiri Hanika, Dicyclopentadiene hydrogenation in trickle-bed reactor under forced periodic control, 2007, Scheme 1, 216, DOI:10.2478/s11696-008-0013-3

- ↑ Hon-Chung Tsui and Leo A. Paquette, Reversible Charge-Accelerated Oxy-Cope Rearrangements, 1998, 9968, DOI:10.1021/jo982002w

- ↑ H. B. Burgi, J. D. Dunitz, J.M. Lehn and G. Wipff, Stereochemistry of Reaction paths at carbonyl centres, 1974, 1567, DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)90678-7

- ↑ Kristen L. McCaleb and Randall L. Halcomb, Intramolecular Ketene-Allene Cycloadditions, 2000, 2631-2634, DOI:10.1021/ol000145a

- ↑ Michael J. Minch, Orientational Dependence of Vicinal Proton-Proton NMR Coupling Constants: The Karplus Relationship, 1994, 41-56, DOI:10.1002/cmr.1820060104