Rep:Mod:ASb34ch3s1

Introduction

The aim of this computational experiment is to characterise transition structures on potential energy surfaces for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and Diels Alder cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and butadiene and cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride. In a chemical reaction, the transition state corresponds to the maximum point of energy along a reaction coordinate. The transition structure for a reaction provides useful information in regards to the chemistry of reactions, for example the rates at which chemical reactions occur. However, transition states cannot be directly observed and therefore computational chemistry is used to elucidate physical data, for example energies, by locating the structures of a reaction that resemble the highest point of energy on a potential surface. In this experiment a program called Gaussview was used to determine the transition structure by optimising a structure that closely resembles the transition state; either the reactants or products depending on whether the transition state is early or late. Another way of locating the transition structure was also used which involved specifying the reactants and products for a particular reaction and the calculation will interpolate between the two structures to try to find the transition state between them. This method is called QST2 and involves numbering the reactant and product molecules. The Hartree-Fock (HF), Density Function Theory (DFT) and Semi-Empirical (SE) levels of theory, for example HF/3-21G, B3LYP/6-31G(d) and AM1, were used to carry out these calculations via the Gaussview program.

Nf710 (talk) 21:59, 2 December 2015 (UTC) It would have been nice here if you could have shown some understanding of what computational methods you were using here.

The Cope Rearrangement Tutorial

Background

The Cope rearrangement is a well studied reaction used extensively for organic synthesis and involves a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of 1,5-dienes. It was discovered by Arthur Cope in 1940 and is shown in figure 1. The Woodward-Hoffmann rules can be used to predict the barrier heights of pericyclic reactions based on orbital symmetry. Therefore, these rules can be used to determine whether a chemical reaction is thermally allowed; if the total number of (4n + 2)s + (4n)a components is odd then the reaction is thermally allowed by the Woodward-Hoffman rules (where n is an integer, a represents the antarafacial component and s represents the suprafacial component). For the Cope rearrangement there are 2 antarafacial components (π2a)and 1 suprafacial component (σ2s)and so the reaction is thermally allowed since the total number of components is odd.

Nf710 (talk) 22:00, 2 December 2015 (UTC)Nice understanding of the chemistry

Optimising the reactants and products for 1,5-hexadiene

Optimise using HF/3-21G level theory

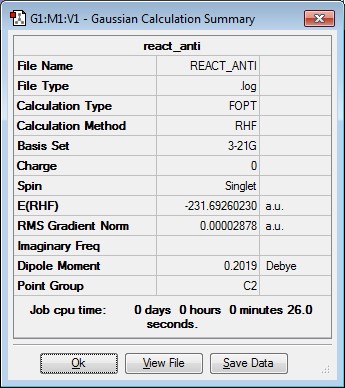

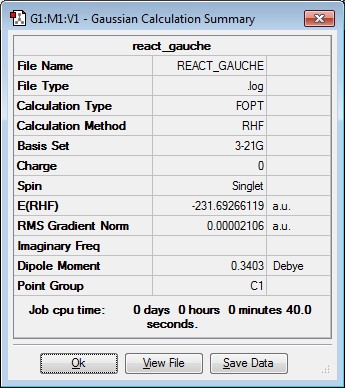

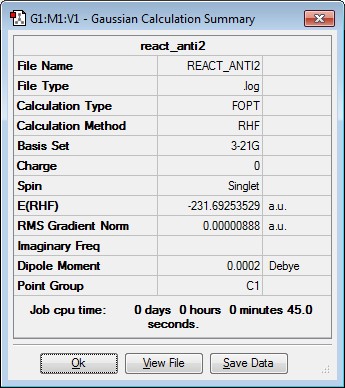

A molecule of 1,5-hexadiene was drawn using Gaussview with an anti linkage and in an approximately p.p conformation for the central 4 carbon atoms. This was done by using a dihedral angle of 180 degrees. The resulting structure was the optimised using HF/3-21G. This corresponds to the anti1conformer. The same process was repeated but this time a gauche linkage was created by using a dihedral angle of 60 degrees. This corresponds to the gauche3 conformer. The gauche conformer would be expected to have a higher energy than the anti conformer due to the greater steric hindrance present. However, from the computational results obtained it was found that the gauche3 conformer has a lower energy than anti1 conformer. This is due hydrogen bonding occurring between the vinyl hydrogens and the pi cloud of electrons on the hydrocarbon chain which results in a stabilisation and hence explains the observed result[1]. Finally, the anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene was drawn in Gaussview and optimised as before. The results are summarised in the table below.

Nf710 (talk) 22:04, 2 December 2015 (UTC) Its not hydrogen bonding but you have used the correct reference and i understand what you mean. That reference is old if you look in the .chk file at the orbitals you can clearly see that it is due to favourable pi pi interactions.

| Conformer | Jmol Structure | Energy(a.u.) | Point Group | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti1 | -231.69260230 | C2 |

| |||

| gauche3 | -231.69266119 | C1 |

| |||

| anti2 | -231.69253529 | Ci |

|

Nf710 (talk) 22:09, 2 December 2015 (UTC) Great use of Jmols

Reoptimise anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene at B3LYP/6-31G

The anti2 conformation of 1,5-hexadiene optimised above was reoptimised at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level, the results of which are summarised in the table below.

| Conformer | Jmol Structure | Energy(a.u.) | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anti2 | -234.61171062 |

|

The final structures from the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d)levels of theory can be compared through bond lengths and dihedral angles. The energies of the different levels of theory cannot be compared.

Comparison of Bond Lengths

| Bond Lengths (Å) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atoms | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1-C2 | 1.31614 | 1.33350 |

| C2-C3 | 1.50888 | 1.50420 |

| C3-C4 | 1.55289 | 1.54816 |

The bond length of the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene calculated by HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d)levels of theory is shown in the table below. The atoms are labelled in accordance with figures 2 and 3 above. From the results obtained it can be seen that the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory gives a longer bond length for C1-C2, but a shorter bond length for C2-C3 and C3-C4, when compared to the HF/3-21G level of theory. This is in agreement with literature (C1-C2:1.34Å, C2-C3: 1.51Å, C3-C4: 1.54Å)[2]. However, the C2-C3 and C3-C4 bond lengths are very similar for both levels of theory. Therefore, from this it can be deduced that the B3LYP/6-31G(d)level of theory should be used for molecules containing multiple bonds with the HF/3-21G level of theory being sufficient for molecules containing just single bonds.

Nf710 (talk) 22:06, 2 December 2015 (UTC) you got the correct energy here and great comparison of geoms and angles

Comparison of Dihedral Angle

The dihedral angle of the anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene calculated by HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d)levels of theory is shown in the table below. The atoms are labelled in accordance with figures 2 and 3 above. The data suggests that B3LYP/6-31G(d) produces a dihedral angle closer to 120 degrees which agrees more closely to the experimental data present (an sp2 hybridised trigonal planar atom is expected to have an dihedral angle of about 120 degrees)[2].

| Dihedral Angle (°) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Atoms | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1-C2-C3-C4 | 114.62561 | 118.59953 |

| C2-C3-C4-C5 | 179.99399 | 180.00000 |

Frequency Analysis of anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene

A frequency calculation of the optimised B3LYP/6-31G(d) structure of 1,5-hexadiene was run. There are no imaginary frequencies at a true minimum, but there will be imaginary frequencies at the maxima on a potential energy surface and real positive frequencies at the minima. A transition state corresponds to the presence of an imaginary frequency. From figure 4 it can be seen that there are no imaginary frequencies present. The infrared spectrum shown in figure 5 suggests that the vibrational stretch of the molecule involves a change in dipole moment as indicated by the non-zero values. The thermochemistry data is summarised in the table below.

Thermochemical Analysis of anti2 conformer of 1,5-hexadiene

| 298K | 0K | |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-Point Energies (Hartree) | 234.469215 | 234.469215 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies (Hartree) | 234.461867 | 234.469215 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies | 234.460922 | 234.469215 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies | 234.500800 | 234.469215 |

Nf710 (talk) 22:11, 2 December 2015 (UTC) excellent doing the thermal corrrections

Optimising the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

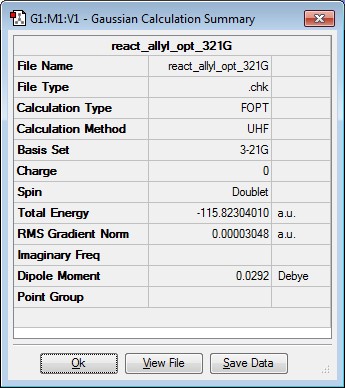

Optimising the allyl fragment

An allyl fragment was produced and optimised using the HF/3-21G level of theory. The results are summarised in the table below. The point group was C2v.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Optimising the "chair" transition structure

HF/3-21G Optimisation

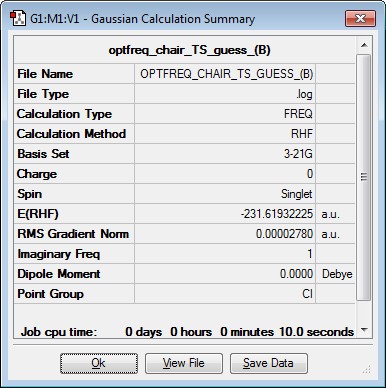

The optimised allyl fragment from above was duplicated to give 2 identical allyl fragments. An estimated structure for the chair transition state was produced by ensuring that the 2 fragments were separated by an estimated 2.00Å in a staggered conformation. The resulting structure was then computed using a Berny optimisation, the result of which is summarised below. An imaginary frequency of -818.01cm-1 was found, confirming that the transition state had been located successfully. Thus, the imaginary frequency represents the maxima on a PES and results in a negative force constant which indicates a transition structure

- [3] where ω is the vibrational frequency, k is the force constant and μ is the reduced mass

The square root of the force constant needs to be taken in order to get the frequency. However, the force constant is negative and so the square root of a negative number gives an imaginary solution and hence an imaginary frequency is obtained.

Nf710 (talk) 22:12, 2 December 2015 (UTC) Good understanding, the force constant is the second derivative of the energy

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -818.01cm-1 leading to the Cope Rearrangement |

Frozen Coordinates Chair Optimisation

The transition structure was optimised again using the frozen coordinates method. In this method, the distance between the allyl fragments where the bonds were being broken/formed was set and fixed to 2.20Å. After this optimisation, the structure was reoptimised in which the bonds being broken/formed are optimised separately. The results are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -817.88cm-1 leading to the Cope Rearrangement |

Bond Breaking and Forming Length Comparisons of Guess and Frozen Optimisation for the Chair Transition State

The bond forming and bond breaking lengths for both methods are summarised in the table below. From the data it can be seen that bond breaking length for both methods are very similar , but the bond forming length for the frozen method is larger. However, the structures produced by both methods are mostly identical.

| Method | Bond Breaking Length (Å) | Bond Forming Length (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Guess Transition Structure | 1.38926 | 2.02105 |

| Frozen Transition Structure | 1.38929 | 2.02074 |

Optimising the "boat" transition structure

QST2 Method

The boat transition structure was optimised using the QST2 method. This method involves specifying the reactants and products for a reaction and specifying the atoms with numbers, as shown below. The calculation performed then interpolates between the two structures to try and find the transition state between them.

| Atom Numbering of the reactant | Atom Numbering of the product |

|---|---|

|

|

The first QST2 calculation fails as shown by figure 6, which shows a dissociated chair transition state. It seems as though when the calculation linearly interpolated between the two structures, it simply translated the top allyl fragment and has not considered the possible rotation around the central bonds. Therefore, in this case the boat transition state will never be reached. Also, this transition state structure does not represent the Cope rearrangement.

Nf710 (talk) 22:18, 2 December 2015 (UTC) very clear and well laid out comparison. Your energies and imaginary frequencies are correct.

Nf710 (talk) 22:19, 2 December 2015 (UTC) very clear and concise comparison your energies and frequencies are correct.

The reactant and product molecules from above were modified, as shown below, such that they resemble the boat transition structure more closely. The results are summarised below. In this case, an imaginary frequency was present at -839.75cm-1 which confirms that the boat transition structure had been successfully found.

| Atom Numbering of the reactant | Atom Numbering of the product |

|---|---|

|

|

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -839.75cm-1 leading to the Cope Rearrangement |

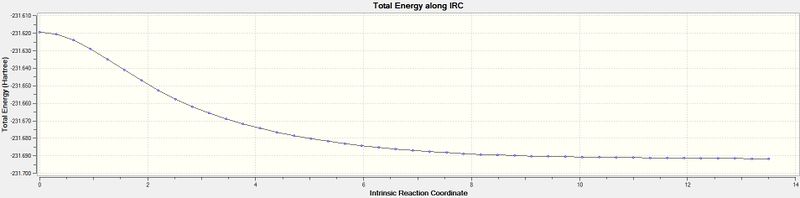

IRC of Optimised "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

The Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) method creates a series of points by taking small geometry steps in the direction where the gradient of the energy surface is the steepest. The IRC method was used for the optimised transition structures from above. The calculation converged after 44 points along the IRC. The reaction coordinate is symmetrical and so the calculation only had to be computed in the forward direction. The total energy and an RMS gradient norm along IRC are shown in figures 7 and 8 below. From this it can be seen that the energy converges to a minimum while the RMS converges to zero, which indicates that the reaction had reached a minimum geometry.

Nf710 (talk) 22:22, 2 December 2015 (UTC) Nice IRC but you could have deduced the conf. that it connects by looking at the energy and comparing it to the marks scheme.

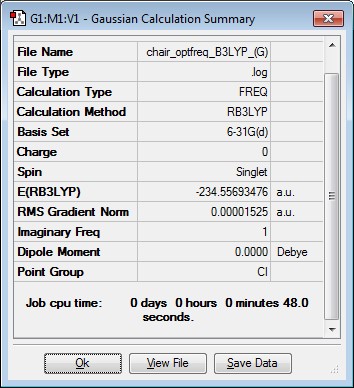

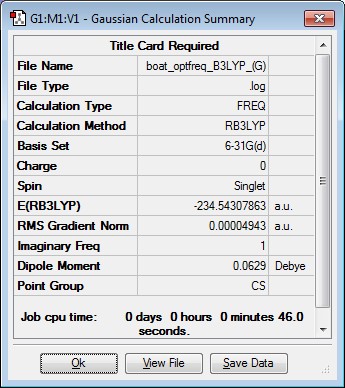

Activation Energy for the reaction via both transition states

The activation energies for the Cope rearrangement were calculated via the chair and boat transition structures. This was achieved by reoptimising the chair and boat transition structures using B3LYP-6-31G(d) level of theory and carrying out frequency calculations. The results are summarised below

Chair Transition Structure Reoptimisation

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -567.54cm-1 leading to the Cope Rearrangement |

Boat Transition Structure Reoptimisation

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -534.94cm-1 leading to the Cope Rearrangement |

From the tables above it can be seen that geometries of both structures are reasonably similar. However, the imaginary frequency and electronic energies are somewhat different.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (Hartree) | Electronic energy (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies at 0 K (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies at 298.15 K (Hartree) | |

| Chair TS | -231.61932225 | -231.466703 | -231.461342 | -234.55693476 | -234.414883 | -234.408960 |

| Boat TS | -231.60280234 | -231.450932 | -231.445302 | -234.54307863 | -234.402316 | -234.395977 |

| Reactant (Anti2) | -231.69253529 | -231.539540 | -231.532567 | -234.61171166 | -234.469215 | -234.461867 |

The activation energies in the table below were calculated from the table above by working out the difference in energy between reactant (anti2) and the chair/boat transition state at the HF/3-21G and B3LYP/6-31G(d) levels of theory.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G* | Expt. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | 298.15 K | 0 K | |

| ΔE (Chair)(kcal/mol) | 45.70587303 | 44.69432853 | 34.09381899 | 33.20150119 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| ΔE (Boat)(kcal/mol) | 55.60231747 | 54.75957289 | 41.97972459 | 41.34845054 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

From the table above it can be concluded that activation energy between the two levels of theory at a given temperature is remarkably different. Additionally, it can be seen that B3LYP/6-31G(d) agrees more closely to the experimental values given, and thus can be considered as a more accurate level of theory. Also, the activation energy at 0K is slightly higher than at 298.15K and so more energy is required to reach the transition state at 0K since less energy is available. Lastly, the reaction pathway via the chair transition state is much more favourable than the reaction pathway via the boat transition states due to a lower activation energy required to reach the chair transition state.

Nf710 (talk) 22:35, 2 December 2015 (UTC) your energies are correct. well done. you didnt compare the geoms of the levels of theory at the TS. but good work!

Nf710 (talk) 22:35, 2 December 2015 (UTC) In general a very clear and well laid out report. was very easy to read. you made a good attempt at understanding the theory also well done.

Comparison of HF and DFT Levels of Theory

Density Function Theory is a higher level of theory since it gives more accurate results, even though it is more expensive. The HF level of theory involves solving the Schrodinger equation by simplifying the interactions between the electrons. HF involves using the kinetic energy of the electrons, the electron-nuclei interaction and the coulomb interaction between electron clouds. On the other hand, DFT uses the Born-Oppenheimer approximation and involves using the same terms as above but also includes the exchange correlation which is the potential due to spin and charge. In DFT the energy of an electronic system can be written in terms of the electronic probability density. This all results in a more accurate result using DFT.

Nf710 (talk) 22:29, 2 December 2015 (UTC) HF uses the BO approx, stating that nucl are stationary to the electrons relatively. DFT is better than HF because HF over estimates the elctronic repulsion due to it being treated as a mean field of all the electrons, which it should be N-1. DFT calculates this term and otehr by using functionals of the electron density. HF cannot correlate probabitly of 2 electons of opposite spins spatial dependance and therefore gets this term wrong as two electrons can theretically be in the same place at once with opposite spins and have no repulsion. Good underdstanding.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Background

The Diels-Alder reaction was first described by Otto Diels and Kurt Alder in 1928. This reaction is a useful synthetic strategy for forming 6-membered rings. The reaction is a stereospecific pericyclic reaction between a conjugated diene and a substituted alkene to form a substituted cyclohexene system. In this computational study, two Diels-Alder reactions will be studied as shown by figures 8 and 9 below. The driving force for this [4+2] cycloaddition reaction is the formation of new sigma bonds, which are more energetically stable than pi-bonds. Furthermore, the substituent on the dienophile can be directed away from the diene in an exo fashion, or towards the diene in an endo fashion.

Diels-Alder reaction between cis-butadiene and ethene

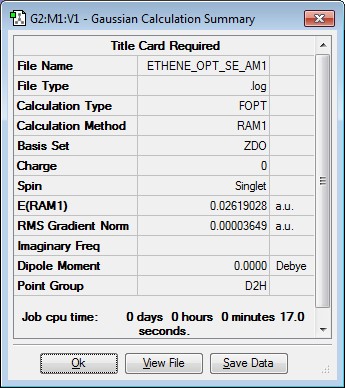

Optimising the structure of ethene

A molecule of ethene was drawn using Gaussview and the structure optimised using the semi-empirical (SE) AM1 level of theory. The results along with the orbitals are shown below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| HOMO of Ethene (Symmetric) | LUMO of Ethene (Antisymmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

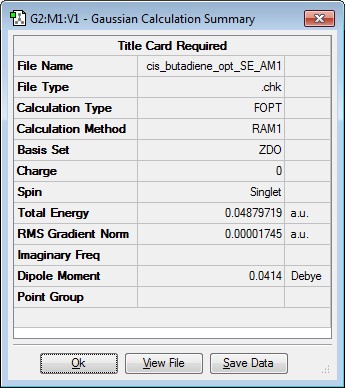

Optimising the structure of cis-butadiene

A molecule of cis-butadiene was drawn using Gaussview and the structure optimised using the semi-empirical (SE) AM1 level of theory. The results along with the orbitals are shown below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C2v |

| HOMO of Cis-butadiene (Antisymmetric) | LUMO of Cis-butadiene (Symmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

Transition Structure Optimisation

The ethane and cis-butadiene structures optimised above were then used to compute the transition state geometry, the results of which are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory (FMO)can be used to predict the outcome of chemical reactions and is based on interaction between orbitals from the reactant molecules. For normal electron demand cycloaddition reactions the diene HOMO interacts with the LUMO on the dienophile. Interactions will be favourable for orbitals that are in phase and of similar energy. The table below shows the HOMO and LUMO for the transition structure of this Diels-Alder reaction. From this is can be observed that the HOMO of the transition structure consists of the cis-butadiene HOMO and the ethene LUMO. By contrast the LUMO of the transition structure consists of the cis-butadiene LUMO and ethene HOMO. In accordance with FMO Theory, this reaction is allowed because the HOMO of one species interacts with the LUMO of another species within the transition state.

(Mention here that the interacting orbitals must be of the same symmetry, so the overlap integral is non-zero Tam10 (talk) 17:18, 26 November 2015 (UTC))

| HOMO of Transition Structure (Antisymmetric) | LUMO of Transition Structure (Symmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

An imaginary frequency was found, as shown below, which confirms that this is indeed the transition structure. Additionally, it can be seen that formation of the carbon-carbon bonds are synchronous. The imaginary frequency vibration shows the movement of the carbon atoms involved in the bond formation process. In contrast, the lowest positive frequency does not show any such movement representing bond formation and hence this vibration is not significant for the bond formation/bond breaking process.

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -955.66cm-1 leading to the Diels-Alder reaction |

Lowest Positive Frequency Vibration at 147.23cm-1 |

| Atom Number | Bond Lengths(Å) |

|---|---|

| C1-C2 | 1.38188 |

| C2-C3 | 1.39750 |

| C5-C6 | 1.38288 |

| C1-C6 | 2.11949 |

| C1-H13 | 1.09888 |

| C2-H12 | 1.10183 |

| C5-H14 | 1.09963 |

The bond lengths between the atoms, shown in the table above, were computed using the atom numbering scheme shown in figure 10 above. The typical length for an sp3 hybridised carbon-carbon bond is 1.54Å, while that of an sp2 carbon-carbon bond is 1.34Å[4]. Therefore, the carbon atoms for this transition state are roughly sp2 hybridised since the carbon-carbon bond lengths in the table above are closer to an sp2 carbon. Additionally, the bond forming length is 2.12Å which is less than double the van der Waals radius of a carbon atom. The van der Waals radius of a carbon atom is 1.70Å[5]. Thus, the terminal carbon atoms in this transition structure are attracted to each other via an interaction which favours the sigma bond formation.

Diels-Alder reaction between Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

Optimising the structure of cyclohexa-1,3-diene

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene was drawn using Gaussview and the structure optimised using SE AM1 level of theory. The results along with the MOs are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

C2 |

| HOMO of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene (Antisymmetric) | LUMO of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene (Symmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

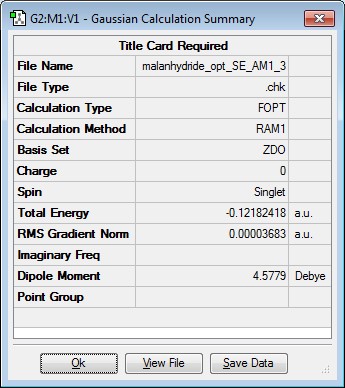

Optimising the structure of maleic anhydride

Maleic anhydride was drawn using Gaussview and the structure optimised using SE AM1 level of theory. The results along with the MOs are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | Point Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CS |

| HOMO of maleic anhydride (Symmetric) | LUMO of maleic anhydride (Antisymmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

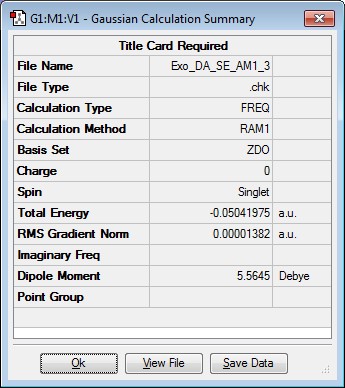

Optimising the structure of exo transition state

The optimised maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene structures were inserted into Gaussview and put into an exo arrangement. This was then optimised using SE AM1 level of theory. The results are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| HOMO of Exo Transition Structure (Antisymmetric) | LUMO of Exo Transition Structure (Antisymmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -812.32cm-1 leading to the Diels-Alder reaction |

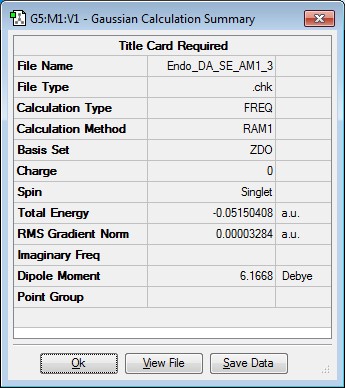

Optimising the structure of endo transition state

The optimised maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene structures were inserted into Gaussview and put into an endo arrangement. This was then optimised using SE AM1 level of theory. The results are summarised below.

| Jmol Structure | Results Summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| HOMO of Endo Transition Structure (Antisymmetric) | LUMO of Endo Transition Structure (Antisymmetric) |

|---|---|

|

|

Imaginary Frequency Vibration at -806.62cm-1 leading to the Diels-Alder reaction |

Comparison of the exo and endo transition structures

Relative Energies of the exo and endo transition structures

| Transition Structure | Energy (Hartree) | Relative Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| exo | -0.05041975 | 0.68 |

| endo | -0.05150408 | 0.00 |

The table above indicates that the endo transition state is lower in energy relative to the exo transition state by approximately 0.68 kcal/mol. Therefore, from this it can be deduced that the reaction pathway via the endo transition state is the kinetic pathway for this reaction.

Thermochemistry Data

| AM1 Semi-Empirical | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic energy (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies (Hartree) | Sum of electronic and thermal energies (Hartree) | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | ||

| Exo TS | -0.05041975 | 0.134880 | 0.144881 |

| Endo TS | -0.05150408 | 0.133493 | 0.143683 |

| Reactant (cyclohexa-1,3-diene) | 0.02771129 | 0.152502 | 0.157725 |

| Reactant (maleic anhydride) | -0.12182418 | -0.063346 | -0.058192 |

| AM1 Semi-Empirical | AM1 Semi-Empirical | |

| at 0 K | at 298.15 K | |

| ΔE (Exo TS)(kcal/mol) | 28.69222152 | 28.45627813 |

| ΔE (Endo TS)(kcal/mol) | 27.82186653 | 27.70452235 |

From the tables above it can be seen that the exo transition state has a higher activation energy which in turn confirms that the kinetic reaction pathways occurs via the endo transition state. Additionally, this data suggests that the steric repulsion in the exo transition state destabilises it relative to the endo transition state in which secondary orbital effects are present.

Bond Lengths

| Atom Numbering of the Exo Transition State | Atom Numbering of the Endo Transition State |

|---|---|

| Error creating thumbnail: File with dimensions greater than 12.5 MP |

|

For Exo Transition State:

| Atoms | Bond Lengths (Å) |

|---|---|

| C5-C6 | 1.39674 |

| C4-C5 | 1.39442 |

| C3-C4 | 1.48973 |

| C2-C3 | 1.52210 |

| C4-C17 | 2.92088 |

| C16-C17 | 1.41015 |

| C15-C16 | 1.48823 |

| C2-C15 | 3.48538 |

| C15-O23 | 1.22054 |

| C15-O19 | 1.40964 |

(The labelling for each molecule is swapped between endo and exo here, so the corresponding bond-forming C-C lengths should also be swapped. You've measured the diagonal. As you have the Jmol, I can make the measurement so it's not a big deal. Just be careful also that you're stating a very high precision Tam10 (talk) 17:18, 26 November 2015 (UTC))

For the endo transition state:

| Atoms | Bond Lengths (Å) |

|---|---|

| C5-C6 | 1.39718 |

| C4-C5 | 1.39311 |

| C3-C4 | 1.49061 |

| C2-C3 | 1.52297 |

| C4-C17 | 2.16223 |

| C16-C17 | 1.40850 |

| C15-C16 | 1.48917 |

| C2-C15 | 3.89616 |

| C15-O23 | 1.22058 |

| C15-O19 | 1.40897 |

From the data in the tables above it can be seen that the bond forming length (C4-C17) is much smaller in the endo transition state when compared to the exo transition state. Also, there is greater steric hindrance in the exo transition structure since the bond forming between the two carbon atoms is longer (C4-C17) and so the maleic anhydride and cyclohexa-1,3-diene reactant molecules are further apart in the exo transition state in order to minimise this steric interaction. Furthermore, there could be a potential interaction between the lone pairs on oxygen in maleic anhydride and sp3 carbon atoms on cyclohexa-1,3-diene. This effect is likely to be small, however, it is more significant in exo transition state due to the geometry of this transition state.

Secondary Overlap Effect

The secondary orbital overlap effect is a stabilising effect resulting from overlap of pi-orbital. The secondary orbital overlap effect should be present in the HOMO of the endo transition state. But there is no in-phase interaction between the pi-orbitals of the diene and the pi-orbitals of C=O. The fact that no such interaction is present suggests that there is no attractive interaction between these carbon atoms.

Semi-Empirical AM1 Level of Theory

The SE AM1 level of theory is a simplified version of HF which uses parameters from empirical data to improve performance. This theory is based on the Neglect of Differential Diatomic Overlap (NDDO) integral approximation and is a Zero Differential Overlap (ZDO) method, in which two electron integrals are neglected. In comparision to HF, SE methods appears to allow the inclusion of elctron correlation effects and the calculations are faster[6].

Conclusion

In this computational experiment the Gaussview program was used to study the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and Diels-Alder reactions. Different levels of theory were used but the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory was the most accurate because it produced results that agreed very well with experimental data, in this case the activation energy. Contrastingly, the HF/3-21G level of theory did not produce the same accuracy and gave activation energy values that deviated from experimental. Stationary points were located on the potential energy surface for the Cope rearrangement and the minima on the PES represented positive frequencies while the maxima on the PES represented imaginary frequencies. The presence of an imaginary frequency confirmed the location of the transition state. This vibration represented the Cope rearrangement reaction.

After this, the Diels-Alder reactions of ethene with cis-butadiene and maleic anhydride with cylcohexa-1,3-diene were studied. It was deduced that for the maleic anhydride with cyclohexa-1,3-diene reaction endo conformer had a lower activation energy and it was found that the exo transition state had greater steric repulsion within the structure. Also, it was found that FMO theory could not be applied due to the nodal properties of the HOMO between the carbonyl fragment and the rest of the system. In contrast, for the Diels-Alder reaction between ethene and cis-butadiene the FMO theory could be used to predict the outcome of the reaction via the HOMO and LUMO transition structures.

The computational experiment can be improved by using the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level of theory for the Diels-Alder reaction in order to get data that would agree more to the experimental results. Additionally, the study could be extended by investigating a wider variety of dienes and dienophiles.

References

- ↑ B. G. Rocque, J. M. Gonzales, H. F. Schaeffer III, Mol. Phys., 2002, 100(4), 441-446.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 G. Schultz, I. Hargittai, J. Mol. Struct., 1995, 346, 63-69.

- ↑ Hollas, J. M. Modern Spectroscopy (3rd ed.),1996, p. 21.

- ↑ F. H. Allen, O. Kennard, D. G. Watson, L. Brammer, A. G. Orpen, R. Taylor, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1987, S1-S19.

- ↑ R. S. Rowland, R. Taylor, J. Phys. Chem., 1996, 100(18), 7384-7391

- ↑ J. Pople and D. Beveridge, Approximate Molecular Orbital Theory, McGraw-Hill, 1970