Rep:Mod:AC2015WK

Determination of the Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of Magnesium Oxide

Introduction

Computational software was used to investigate how the structure of magnesium oxide (MgO) changes upon heating. The phonon modes were approximated from a model of atomic interactions based on ionic bonding and visualised as dispersion curves and as a density of states. From the density of states, a grid size of 16:16:16 was found to be suitable for the subsequent calculation of physical properties. This included the free energy, lattice parameters and cell volume of MgO at a range of temperatures via both quasi-harmonic (QH) and molecular dynamics (MD) methods.

| Quasi-Harmonic | Molecular Dynamics | % Difference |

|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz Free Energy (eV) | 0.01 | |

| -40.9265 | -40.9205 | |

| Lattice parameter (Å) | 10.81 | |

| 2.9834 | 2.6609 | |

| Molar Volume (Å3) | 0.26 | |

| 18.8900 | 18.8406 | |

The results from both approaches are shown to be fairly consistent, with thermal expansion coefficients found to (α) equal 6 x 10-4 K-1 at a high range of temperatures and which only reduced to 4 x 10-4 K-1 at low temperatures for the QH method. The two approaches generated nearly equivalent lattice properties as visible in Table 1. The free energy calculated is within the same order of magnitude as literature values [1] [2] which is fairly accurate considering the approximations made. However, the methods gave opposite trends for the variance of free energy with temperature and reasons for this are discussed.

Physical Background

Magnesium oxide exists as a crystalline structure with a high melting point of 3125K [3]. The underlying crystal structure of MgO is based upon a periodic motif called the unit cell. The primitive unit cell is the most basic motif that can be repeated to describe the lattice, but it may not have the same symmetry operations as the entire lattice. A combination of primitive unit cells that do invoke the symmetry of the crystal is known as a conventional cell, whilst on an even larger scale a supercell consists of numerous primitive cells. The crucial point to note is that calculations performed on the primitive unit cell are sufficient to describe the entire crystal (which is simply a multiple of primitive cells).

The GULP program minimised the energy of the MgO primitive cell to give it the following vectors at a pressure of 0 GPa and temperature of 300K:

0.0000 2.1060 2.1060

2.1060 0.0000 2.1060

2.1060 2.1060 0.0000

These specify the fundamental geometry of the magnesium and oxygen atoms upon which the conventional cell (and thus the entire structure) is founded.

Thus the QH calculations in this experiment were performed on rhombohedral primitive cells of side length ap = bp = c/p = 2.9783 Å and internal angle αp = βp = γp = 60° . These primitive cells combined to give a cubic conventional cell, which was the basis of the MD calculations. In this instance the conventional cell gave a cube with four times the volume of the primitive cell and a lattice constant of ac = 4.212 Å. These ideal cells were assumed to be periodic with no defects.

Atoms naturally fluctuate about their equilibrium positions to give vibrations of a specific frequency and with a unique k label. These vibrations are known as phonons and can be used to calculate many physical properties. In this investigation phonon modes are used to determine the the free energy. Since the crystal is modelled on a repeating unit cell, a summation of k values gives the overall expansion (or contraction) of the crystal at given parameters of temperature or pressure. Increasing the temperature results in an increase in the average amplitude of vibrations, observable as an increased interatomic distance and expansion of the material. This expansion continues up to the melting point at which stage the potential energies are much larger than at equilibrium, causing the interatomic interactions to break down and a loss of periodicity within the material.

This expansion upon heating is described by the equation:

Where is the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, is the primitive cell volume, is temperature and is pressure.

Since the temperature is varied in this experiment, the pressure is kept constant at 0 GPa. The results obtained were in good concordance previous studies of the structure of MgO [2] [4] [5]

Quasi-Harmonic Methodology

The Mg2+ and O2- ions modelled in this investigation are not motionless entities. At low temperatures, their vibrational energy is small enough to be described by harmonic oscillators. However, as the temperature increases so too does the vibrational amplitude, causing deviations in equilibrium position that are not sufficiently described by the harmonic oscillator[6][7]. The quasi-harmonic model can be used to define the new potential energies. This relies on the harmonic phonon model holding true for all lattice parameters but with volume dependent phonon modes. In this experiment the relative volume is per primitive unit cell.

In a diatomic molecule with an exactly harmonic potential the bond length would not increase with temperature and hence there would be no thermal expansion since there is no deviation from the equilibrium position. Anharmonicity is required to increase the interatomic separation. However the bond length does increase in the solid when using a quasi-harmonic approximation since as the atoms vibrate in non-equilibrium conditions, their potential energies are displaced away from the harmonic model with a resultant increase in interatomic distance.

Molecular Dynamics Methodology

Molecular dynamics is an approach that does not use the harmonic approximation. Instead the method is based on Newtonian physics, with the initial coordinates of the atoms explicitely specified and the initial geometry optimised to find the forces on the atoms. The atoms are then subjected to acceleration using Newton's Second Law of Motion:

Where is the acceleration, is the force and is the mass.

Atomic positions are thus obtained over a series of incremental changes in time to reproduce the random motion of the atoms whose average physical properties are obtained. The timestep in this investigation is set to 1 femtosecond. In addition, the primitive unit cell employed in the quasi-harmonic method is insufficient to calculate atomic vibrations since it would model a crystal in which all unit cells are vibrating uniformly (which is clearly not the case in reality). Instead, a supercell of 32 MgO unit cells was used to sufficiently incorporate the irregular motion of unit cells across the crystal.

This classical treatment of atomic motion is more expensive computationally since every displacement is computed, unlike the quasi-harmonic model which simply sums over a number of k points.

Programs used

The GULP (General Utility Lattice Program) program was used to perform harmonic and molecular dynamic calculations whilst the DLV interface allowed the visualisation and animation of the output MgO cell. The Linux OS was used as an efficient platform for running the calculations.

The force field defining the potential energy of MgO was based on a simple ionic lattice of Mg2+ and O2- ions with an interatomic potential of 6.7212 eV [1] and including Buckingham pair potentials (short-range repulsive forces). The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is utilised and so individual electron-electron repulsions are ignored and instead an individual electron sees repulsion from all other electrons an an electric field. The model was simply loaded onto GULP from a premade file [8]

Density Functional Theory (DFT) may give a more accurate model of the electronic structure, but for a simple ionic system such as MgO the increase in CPU time is unneccesary. However, for the modelling of semiconductors and more complex systems, the limitations of the classical model may necessitate the use of a more sophisticated method incorporating quantum mechanical parameters.

Dispersion Curves

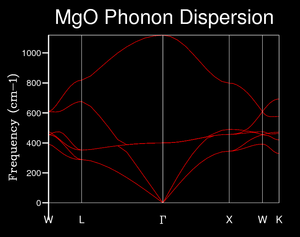

The movement of atoms away from their equilibrium positions can be quantified into discrete units known as phonons. The phonon modes vary across k-space and may be visualised using phonon dispersion curves, which plot this variance in frequency against k. These are also known as curves. For this investigation the phonon modes were modelled across 50 k-points to give a sufficiently comprehensive overview.

It may be seen in Image 2 that each k-point has 6 phonons, and that the phonons are sometimes degenerate (for example, there are only 4 distinguishable phonons at k = L and at k = X). All 50 k-points are represented along the x-axis. The rationale behind 6 phonons is that each unit cell contains 2 atoms (one magnesium and one oxygen) which can both vibrate along 3 directions (x, y and z) to give 6 possible vibration bands.

Density of States

The density of states (DOS) displays the frequency of phonon modes across every k-point. It can be applied to dispersion curves to give a snapshot of all the vibrational modes at each frequency for a given value of k.

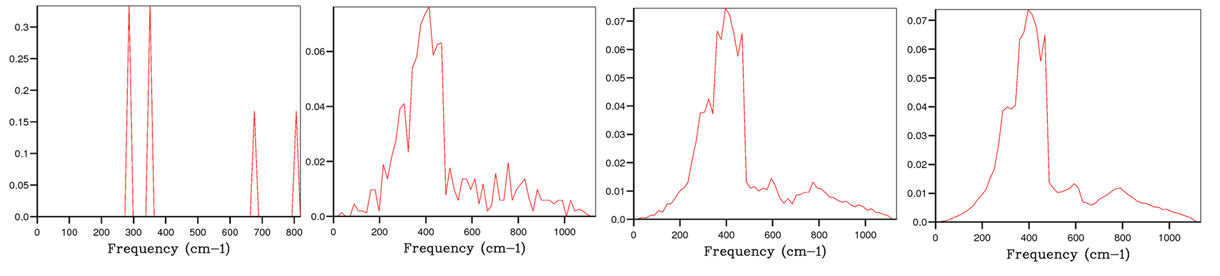

For example the DOS in Image 3(i) represents the k-point at L in the phonon dispersion graph (Image 2). There are vibrational modes at roughly 290cm-1, 350cm-1, 680cm-1 and 810 cm-1. The two modes at lower frequencies have double the height of those at higher frequencies since there are 2 degenerate phonon modes at 290cm-1 and 350cm-1, but only one mode each at 680cm-1 and 810 cm-1.

Many physical properties can be calculated from the phonon density of states. However, the accuracy of these calculations depends on the size of the grid selected for the Brillouin zone integration, in which the points are placed equidistantly along x,y and z in the reciprocal space. For systems with large unit cells a small number of points (and sometimes simply one point) will be sufficient since the reciprocal space is small. However, as the unit cell becomes smaller it becomes important to inspect the convergence of the results as a function of grid size. Moreover for symmetrical systems, such as MgO, a smaller grid than expected may be used since the symmetry of the cell means less of the k-space needs to be sampled to accurately describe its vibrations.

Images 3(i)-(iv) show the convergence of the MgO DOS as the grid size increases from a 1:1:1 grid to a 32:32:32 grid. The DOS moves from a discontinuous plot to a continuous one with more k points at more frequencies and at smaller proportions. This is obviously because more of the vibrations are being sampled. Furthermore the energies in Table 2 equilibrate at a grid size of roughly 16:16:16, thus this size is sufficient to describe the DOS. The DOS modelled on 32 points does have a slightly smoother curve, but is computationally more expensive with a CPU time of almost 17 times that of the 16:16:16 grid. It is clear that any increased precision for a grid size of 64 points is negated by the vast computational expense this requires.

Were it necessary to perform calculations on a similar oxide such as CaO, the same optimal grid size of 16 points ought to suffice since the electron and charge distribution will be very similar, and the atomic radii and mass also. These lead to a unit cell with the same symmetry and relative proportions and thus sampling across 16 points should be suitable.

However, a zeolite such as Faujasite in Image 4 has a much larger unit cell since the interatomic separation is far greater, with a vast volume of empty space visible in the molecules. Thus the reciprocal space is smaller than for MgO and a small grid with only a few k points would be required.

For a metal there is only one atom in the unit cell so it may be assumed that more k points would be required to describe the larger reciprocal space. However, the electronic structure of metals is very different to that of an ionic solid such as MgO. In metals the electrons are delocalised across the system and consequently they screen repulsive charges. Therefore the atoms experience less repulsion and vibrate to a smaller extent, giving a phonon dispersion graph with less variance. Nonetheless if the material is a conductor, more than one k point would be required to compute the Fermi energy.

Calculating the Free Energy

The free energy of the crystal is the energy required to pull all of the atoms apart to infinite separation. The QH approximation can be used to determine the free energy of MgO by summing over all the phonon modes in the k-space. Clearly it is impossible to compute a calculation based on a grid of infinite points so a reasonable grid size must be chosen. This was noted to be a grid of 16 points simply by analysing the convergence of free energy, shown in Table 2. These measurements were made at a temperature of 300 K and pressure of 0 GPa:

| Grid Size | Number of k points | CPU time (seconds) | Free Energy (eV) | Free Energy (kJmol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:1:1 | 1 | 0.0021 | -40.9303 | -3949.1480 |

| 2:2:2 | 4 | 0.0029 | -40.9266 | -3948.7918 |

| 3:3:3 | 18 | 0.0062 | -40.9264 | -3948.7747 |

| 4:4:4 | 32 | 0.0089 | -40.9264 | -3948.7764 |

| 8:8:8 | 256 | 0.0677 | -40.9265 | -3948.7791 |

| 16:16:16 | 2048 | 0.6339 | -40.9265 | -3948.7796 |

| 24:24:24 | 6912 | 2.7175 | -40.9265 | -3948.7796 |

| 32:32:32 | >9999 | 10.4666 | -40.9265 | -3948.7796 |

| 64:64:64 | >9999 | 414.3830 | -40.9265 | -3948.7796 |

The QH approximation initially overestimates the free energy, which therefore minimises to a value of -40.9265 eV as the model tends to an infinite lattice. From inspection of Table 2 it can be seen that appropriate grid sizes for the following degrees of precision are:

- To the nearest 1 meV requires a grid of 3:3:3 (to give the free energy = -40.926eV)

- To the nearest 0.5 meV requires a grid of 4:4:4 (to give the free energy = -40.9265eV). In this instance, 3 points are not sufficient and since the number of points must be an integer, 4 points is the minimum appropriate size.

- To the nearest 0.1 meV also requires a grid of 4:4:4

The optimal grid sizes for the calculation of free energy for different substances would be the same as noted previously, since the convergence of free energy and of density of states are very similar.

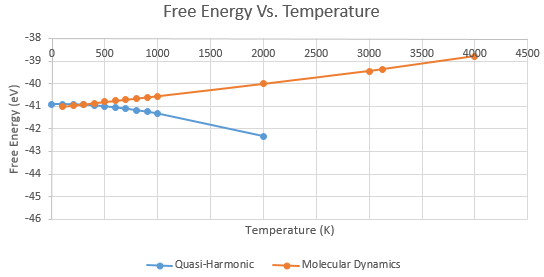

The free energy was computed periodically from 0 to 1000K and then also at higher temperatures up to 2000K to see whether the QH and MD models deviated at higher temperatures. Moreover, the activity near the melting point of 3125K was of interest.

The MD model was based on a supercell containing 32 MgO units and thus the results were all divided by 32 in order to be comparable with the QH results which were based on one MgO unit.

It can be seen in Graph 1 that the two methods gave entirely different trends for the free energy of the crystal as the temperature increased. The QH approximation calculated the change in potential energy to decrease as the atoms moved further away from their equilibrium positions. The increased temperature is modelled as a displacement further away from the harmonic curve. This is not entirely accurate since we are approximating an anharmonic model to an harmonic one. Furthermore the anharmonicity increases with temperature and so the quasi-harmonic model becomes even less accurate. Thus the phonon modes are not a very accurate representation of the ions at higher temperatures.

The MD method showed a reduction in free energy with temperature. This is based on the following formula for kinetic energy:

Where is kinetic energy, is mass, is velocity, is Boltzmann's constant and is temperature. Hence the energy increases with temperature as Boltzmann's constant is positive. However, molecular dynamics is less valid at lower temperatures where it ignores the zero point motions and quantum nature of the phonon modes. This meant that it generated an energy of 0 eV at 0K, unlike the quasi-harmonic method which gave an energy of -40.9019 eV at 0K. This highlights the difference between quantum and classical methods, where there respectively is motion and is no motion at absolute zero.

A Comparison of Lattice Constants

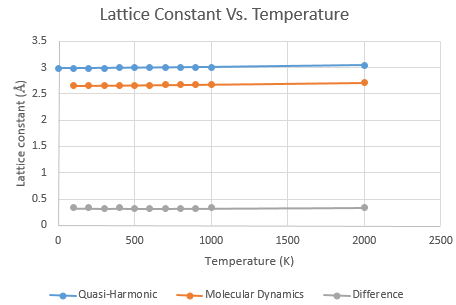

The lattice constant does not vary with temperature since it is the parameter that defines the unit cell. However, the models gave values that differed by 10.81%. This is probably in part due to the fact that the quasi-harmonic approximation is based on a primitive unit cell whilst the molecular dynamic method was based on a cell of 32 units. Thus any discrepencies between the two models was enhanced by the sheer volume of calculations the molecular dynamics model performed.

Calculating the Thermal Expansion Coefficient

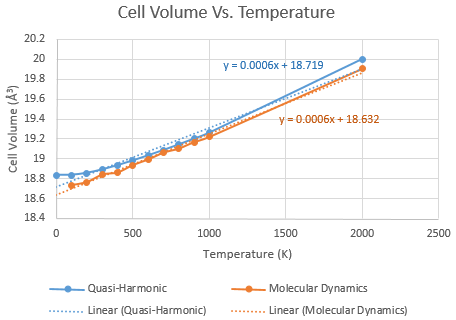

The thermal expansion coefficient was be derived from the cell volumes at the same range of temperatures as the free energy calculations. As detailed above, the thermal expansion coefficient is simply the gradient of a graph of volume versus temperature. The MD results were again scaled down 32 times to give results comparable with the QH calculations. The results are plotted in Graph 3.

A grid of 4 points was not chosen to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient since although it is accurate to 0.1meV, this is the level to which the results are to be reported and so a higher level of precision is required in the calculations. Thus a grid of 16 points was again used in the QH method.

Overall, the thermal expansion predicted by MD and by the QH approximation are very similar, both providing the same thermal expansion coefficient of 6 x 10-4 K-1 for a temperature range between 0 and 2000K. This pleasingly closely agrees with a literature value of 10.4 x 10-6 [9] recorded at 273K. If the result at 2000K is neglected, the QH method gives a thermal expansion coefficient of 4 x 10-4 K-1, whilst the MD coefficient remains at 6 x 10-4 K-1 whether the extra result at 2000K is included or not.

This is since the molecular dynamics method allows the atoms to vibrate in any direction and simply calculates their energies along a timeframe, whilst the quasi-harmonic method sums over k-space and is reliant on the periodic model. This restricts the possible amplitude of any atomic vibrations before they overlap with an adjacent unit cell. Thus as the temperature - and subsequently vibrational amplitude - increase, the quasi-harmonic model ought to break down. However in this investigation, the model calculates the same thermal expansiion coefficient as the MD method up to a temperature of 2000K, so even higher temperatures must be needed to demonstrate this loss of periodicity. Higher temperatures were attempted to be modelled using QH but the CPU time was far too high to generate any results.

The MD method is seen to be fairly linear down to 0K, whilst the QH method gives a slight non-linearity between 0 and 400K. This may be because as the temperature increases, so too does the random motion of atoms to give far more phonon modes that at lower temperatures.

Conclusions

Quasi-harmonic and molecular dynamic approaches were shown to be fairly accurate in calculating the lattice constants and thermal expansion coefficient of MgO. Discrepancies in the results of the two methods were observed, particularly in the variation of free energy with temperature. The MD model was more accurate at higher temperatures whilst the QH model was more accurate at lower temperatures, before the vibrations deviated towards anharmonicity. The calculations were based on the phonon modes of MgO, which were visualised and approximated to a density of states with a grid of 16 points. This grid size showed suitable convergence of both DOS curves and free energy.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bush, T., Gale, J., Catlow, C. and Battle, P. (1994). Self-consistent interatomic potentials for the simulation of binary and ternary oxides. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 4(6), p.831.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Taurian, O., Springborg, M. and Christensen, N. (1985). Self-consistent electronic structures of MgO and SrO. Solid State Communications, 55(4), pp.351-355.

- ↑ Ho, C. and Taylor, R. (1998). Thermal expansion of solids. Materials Park, OH: ASM International. p280

- ↑ Skinner,B.J.,Thermal expansion of thoria, periclaSe,ahd diamond, Am.Mineral.42,39-55,1957.

- ↑ Hemley, R., Jackson, M. and Gordon, R. (1985). First-principles theory for the equations of state of minerals at high pressures and temperatures: Application to MgO. Geophys. Res. Lett., 12(5), pp.247-250.

- ↑ Dove, M. (1993). Introduction to lattice dynamics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Lide, D. (2007). CRC handbook of chemistry and physics. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. pp 9–82

- ↑ Harrison, N. (2015). [online] Ch.ic.ac.uk. Available at: http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/harrison/Teaching/Thermal_Expansion/initial_energy.html [Accessed 19 Oct. 2015].

- ↑ Ho, C. and Taylor, R. (1998). Thermal expansion of solids. Materials Park, OH: ASM International. p280

Appendix

All molecular dynamics results (having been scaled down by a factor of 32):

| Temperature (K) | Energy (eV) | Optimal lattice constant (Å) | Volume per formula unit (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | - | - | - |

| 100 | -41.0238 | 0.3306 | 18.7348 |

| 200 | -40.9712 | 0.3302 | 18.7665 |

| 300 | -40.9205 | 0.3286 | 18.8406 |

| 400 | -40.8658 | 0.3297 | 18.8624 |

| 500 | -40.8119 | 0.3287 | 18.9373 |

| 600 | -40.7631 | 0.3288 | 18.9921 |

| 700 | -40.7113 | 0.3284 | 19.0610 |

| 800 | -40.6601 | 0.3294 | 19.1018 |

| 900 | -40.6062 | 0.3294 | 19.1677 |

| 1000 | -40.5556 | 0.3301 | 19.2193 |

| 2000 | -40.0128 | 0.3369 | 19.9038 |

| 3000 | -39.4454 | n/a | n/a |

| 3125 | -39.3661 | n/a | n/a |

| 4000 | -38.7926 | n/a | n/a |

n/a represents where the CPU time was too long to compute the result

All quasi-harmonic results:

| Temperature (K) | Energy (eV) | Energy (kJmol-1) | Optimal lattice constant (Å) | Volume per formula unit (Å3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -40.9019 | -3946.4087 | 2.9866 | 18.8365 |

| 100 | -40.9024 | -3946.4582 | 2.9866 | 18.8365 |

| 200 | -40.9094 | -3947.1295 | 2.9876 | 18.8562 |

| 300 | -40.9265 | -3948.9380 | 2.9834 | 18.8900 |

| 400 | -40.9586 | -3951.8782 | 2.9916 | 18.9325 |

| 500 | -40.9994 | -3955.8188 | 2.9941 | 18.9801 |

| 600 | -41.0493 | - 3960.6314 | 2.9968 | 19.0312 |

| 700 | -41.1071 | - 3966.2085 | 2.9996 | 19.0851 |

| 800 | -41.1719 | - 3972.4581 | 3.0026 | 19.1413 |

| 900 | -41.2430 | -3979.3207 | 3.0056 | 19.1996 |

| 1000 | -41.3198 | -3986.7336 | 3.0088 | 19.2600 |

| 2000 | -42.3237 | -4083.5871 | 3.0470 | 20.0030 |