Rep:Mod:987ABC

Thermal Expansion of MgO (Author: Natalie Uhlikova)

Introduction

Crystals are infinite structures of atoms that repeat periodically, creating an infinite crystal lattice. Crystals unlike molecules, are described by k-space (also called reciprocal space or momentum space) with lattice parameter a* (where ) where a is the lattice parameter in the real space. Atoms in the lattice don't vibrate independently. The collective vibrational modes of an infinite crystal lattice are called phonons[1], which are equivalent to photons with respect to electronic states. Dispersion relation E(k) curve shows the energy of individual states as a function of k, the wave-vector. The first Brillouin zone lies within a range of unique k values |k| ≥ π/a, any value outside of this interval is only a repetition as the reciprocal space is periodic.The density of states (DOS) is inversely proportional to the E(k) slope.

The atoms in the lattice are attracted to each other by Coulombic forces. To avoid collision of anionic oxygen and cationic magnesium, the Buckingham potential (repulsive force) is employed.

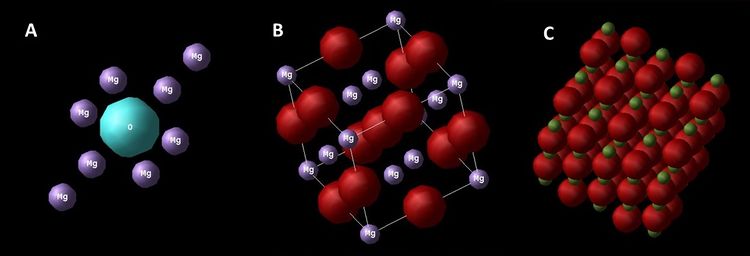

A primitive cell of MgO takes shape of rhombohedron (picture no. 1). It is the smallest cell that can be translated in space to generate the crystal. The primitive unit cell was used for all calculations within the quasi-harmonic mode. A cubic conventional cell is easy to visualise, but not suitable for calculations in this case. Supercell will be employed into molecular dynamics calculations as it is desirable to have a larger system, so that more accurate results can be achieved.

Thermal energy is sum of energy of all vibrational modes present in the crystal at a given temperature. The physical origin of thermal expansion consists in the anharmonic nature of interatomic interaction potential. At higher temperatures, the atoms vibrate with higher amplitude and hence the average value of interatomic separation increases. Thermal expansion coefficient α is given by the following formula:

where V0 (Å3) is the initial cell volume at 0K, V(Å3) is volume at temperature T(K). Partial derivative of volume with respect to temperature is the slope of graph of volume vs. temperature at constant pressure.

Objectives

The aim of this lab is to study thermodynamic expansion of MgO crystal by carrying out computational simulations based on two principles: 1) quasi-harmonic approximation and 2) molecular dynamics.

Methodology

Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QH)

This method approaches crystal dynamics from quantum-mechanical point of view using a reciprocal space. The lattice dynamic of MgO crystal is investigated by approximating that all vibrations are of harmonic nature and can be described by a parabolic function. Helmholtz free energy per unit cell can be calculated as a function of volume and temperature. The unit cell is optimised to find energy minimum at each temperature in the range ∈ <0;2579> K. The Helmholtz free energy A is given by the following formula:

where E0 is the internal lattice energy, the second term represents zero point energy and the third term stands for vibrational entropy; j represents phonon bands, k is abbreviation of k-point in the reciprocal space, ℏ is reduced Planck's constant, ω is angular frequency (rad/s), kB is Boltzmann constant and T is temperature in K.

Limitations to this method: The atoms are not allowed to move, so their equilibrium bond distance does not change as a function of temperature, i. e. the positions of nuclei are fixed and thus bonds are not allowed to break in this approximation.

Molecular Dynamics (MD)

Molecular dynamics obeys the second Newton law F=ma ( where F(N) is force, m(kg) is mass and a(m/s) is acceleration) and investigates average system behaviour over a period of time. The computational simulation operates on a real space where atom positions are not fixed and hence they are allowed to move and bonds can break. The zero point energy is being ignored. Calculation was carried out on a supercell containing 32 MgO units. This number results from a compromise between having enough flexible space for atoms to move and reasonably short time for calculations. The real trajectory of atoms is simulated. The following settings was applied: A time step dt = 10-15 s, which is long enough for calculation to be efficient; 500 equilibration and production steps, 5 sampling steps and trajectory write steps.

Limitations to this method: The zero point energy cannot be calculated.

Results and Discussion

Lattice Dynamics

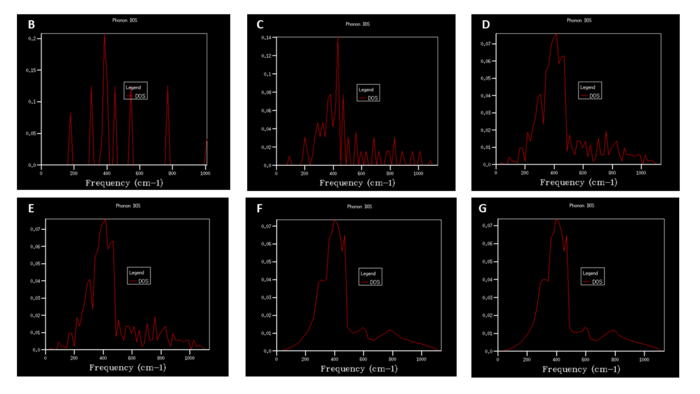

Picture no. 2. shows the phonon dispersion that was computed on 50 k-point. Note that this number of k-points doesn't give the best resolution, but is it just good enough to allow for a reliable phonon dispersion calculation. In general, 6 vibrational branches are observed, occasionally less due to degenerate vibrational modes.

The value of k cannot be changed as it spans over the range ± π/a, but the grid size can be adjusted i.e. it can be changed how many times the E(k) reading is taken via the shrinking factor. The following empirical formula is valid for shrinking factor n>1: no. of k-points =, where n is the shrinking factor, so for example shrinking factor 2 has 4 k-points, n=4 contains 32 k-points etc...

Picture no.3 shows a DOS graph for 1x1x1 grid calculated using a single k-point (0.5,0.5,0.5), which corresponds to a symmetry point L (see picture no. 2). Based on the assumption that as there are two atoms in the unit (Mg and O) in a three-dimensional space, six unique branches (vibrational bands) should be expected. There are only four peaks in the graph at the frequencies 286 and 351 Hz (0.333 intensity) and 676 and 806 Hz (0.167 intensity). The two higher intensity peaks are doubly degenerate, hence only four peaks are observed. The bigger the grid size, the better the 'resolution' of the DOS curve and hence more accurate picture of the states. By changing the grid size gradually by a factor of 2, the DOS curve became progressively smoother. There was no noticeable difference in the shape observed when changing the shrinking factors from 32x32x32 to 64x64x64. As a consequence, the grid size 32x32x32 was established as the optimal grid size and was utilised for all further calculations to achieve high enough resolution in a reasonable time.

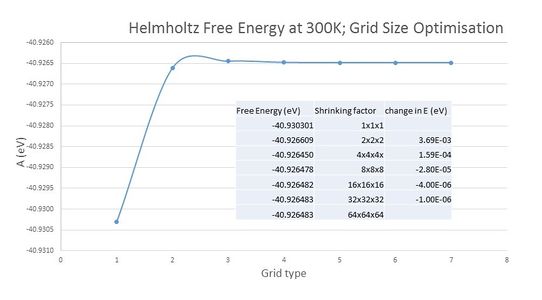

To further justify the above conclusion in a quantitative way, Helmholtz free energy was computed for various grid sizes. The smaller grid sizes displayed significant fluctuations in the free energy values, but it levelled out at -40.926483 eV once a grid size 32x32x32 was reached (picture no. 5). The most dramatic change in free energy appeared at low sampling when grid size was changed from 1x1x1 to 2x2x2. Accuracy in energy determination to 1meV can be achieved with grid 8x8x8, accuracy to 0.5 meV and 0.1 with 16x16x16 grid.

When considering whether the 32x32x32 grid size would be suitable for performing calculations for other crystal structures, the relative size of lattice parameter a in the real space and the inverse equivalent a* in the reciprocal space should be taken into account. It is expected that for a dimensionally similar oxide CaO with a = 4.7-4.8 Å[2] the optimum grid 32x32x32 for MgO should be sufficient to obtain a convenient resolution. Zeolite is a large structure, its lattice constant a ranges between 24.2-25.1 Å[3] for faujasite. MgO lattice constant equals roughly 3 Å, which means that in k-space a* of MgO is bigger than a* of zeolite and thus lower grid-size would be needed for description of zeolite to achieve equally good results as for MgO. The same trend would apply to metals, but with different reasoning behind. In comparison to MgO, the sea of free electrons in metals moderate repulsion between 'stationary' cations and hence lower the width of the band structure. i. e. metals give rise to smaller/narrower band width (and hence higher DOS) and therefore metals can be described by lower number of k-points to achieve a sufficient resolution. The optimal grid size for MgO is suitable for metal DOS simulations.

Molecular Dynamics

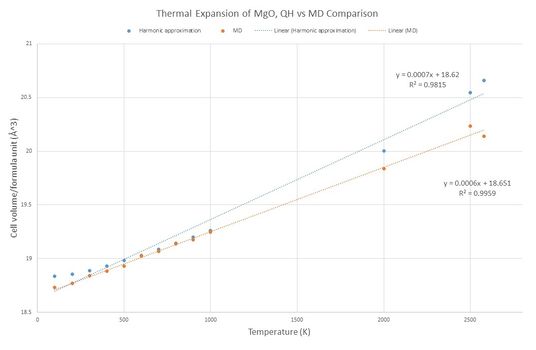

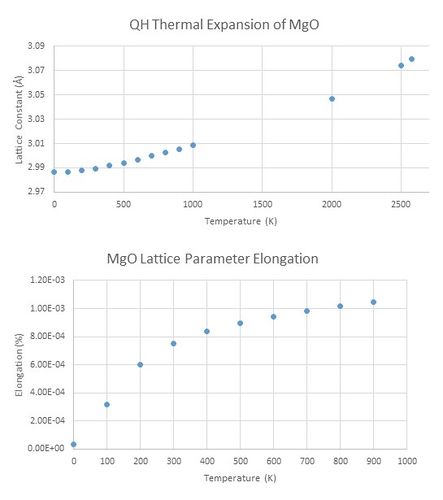

The two curves for MD and QH approximation display a similar linear behaviour (picture no. 6). At lower temperatures, QH line deviates noticeably from the linear fit, whereas MD curve nicely obeys the linear trend. Molecular dynamic simulation is more suitable to perform calculations operating close to the melting temperature, because the bonds are allowed to break. Melting point of MgO is around 3250 K[4]. There is a small drop in the unit cell volume for MD curve at temperatures approaching the melting point (>2600K). Contrary to that the quasi-harmonic curve keeps increasing as atoms are not allowed to dissociate and therefore the lattice parameter increases to the infinity after passing the melting point (picture no. 8).

When using quasi-harmonic approximation, thermal expansion coefficient was found α = 2.654x10-5 K-1, when applying molecular dynamics α = 3.185x10-5 K-1. In comparison to the literature values (both calculated by QH method) 1.334x10-5K-1[5] (extrapolated at T range <300,1000> K) and 1.260x10-5K-1[6] from range at higher temperatures <1000,2000>K, the experimental QH and MD thermal expansion coefficients are of the same magnitude but with slightly higher multiplier.

The size of the supercell (32 MgO units) seems therefore to create a reasonably big sample for the simulation that did not require too much processing time. A supercell structure of 64 MgO units would serve as a more accurate representation of the real crystal structure as there is more freedom of movement and large set of data to be averaged over a period of time. Based on the ease of calculation time for system of 32 units, a supercell containing 64 MgO might be useful and feasible sell size for future calculations.

Conclusion

In this lab the thermal expansion of MgO crystal was simulated using two different methods: phonon-based lattice dynamics (quasi-harmonic approximation) and classical Newtonian molecular dynamics. An optimal grid size that delivered the best resolution in the most reasonable amount of time was found to have shrinking factors 32x32x32. The optimal grid and primitive unit cell was utilised to calculate Helmholtz free energy as a function of temperature in the range <0,2579> K. When using quasi-harmonic approximation, thermal expansion coefficient was found to be α = 2.654x10-5K-1, when using molecular dynamics α = 3.185x10-5K-1. Both values are in good agreement with literature values[1] which suggests calculations were carried out correctly with a sufficient lattice sampling. Molecular dynamic approach predicts thermal expansion better at temperatures closer to the melting point, lattice dynamics is more suitable for low temperatures calculations, particularly at 0K, where molecular dynamics fails to predict the zero point energy.

Reference

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 R. Hoffman, Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 1987, 26, 846-878

- ↑ E. Albuquerque and M. Vasconcelos, Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2008, 100, 42006

- ↑ J. A. Kaduk and J. Faber, The Rigaku Journal, 1995, 12, 14-34.

- ↑ C. Ronchi and Mikhail Sheindlin, Journal of Applied Physics, 2001, 90.

- ↑ A. S. Madhusudhan Rad and K. Narender, Journal of Thermodynamics, 2014, 4.

- ↑ C. J. Engberg and E. H. Zehms, Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 1959, 42, 304.