Rep:Mod:8892 ntmod2

Module 2 Inorganic: Nicole Trainor

Introduction- Computational Methods

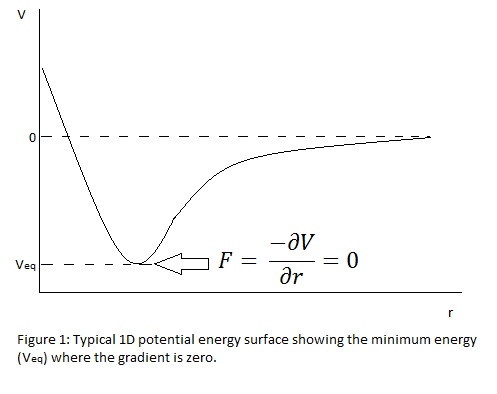

Computational methods of analysis may be applied to a variety of inorganic systems such as small molecules, metal complexes and solid lattices. The results give us insight into the structure, bonding, reactivity and physical properties of these systems to support practical investigations in the laboratory. Before such calculations may be performed, the system parameters must be defined and optimised; for example, the structure is crudely sketched and subjected to density functional calculations which solve Schrodinger's equation for the electronic wavefunctions with fixed nuclei then progressively altering the positions of these nuclei to seek out the minimum energy configuration. The theory is based on the potential energy [V(r)] surface: the minimum energy (most stable state) exists when the forces of the system are at equilibrium. Figure 1 shows this relationship and demonstrates the overall aim of the convergence; each step in the calculation is a change in "r", the nuclear coordinates, along the potential energy surface to the point where the gradient is zero. The model assumes the Born-Oppenheimer approximation in that the nuclei are much larger and so are at rest relative to the speed of electronic movement.

The accuracy of the output relies on the chosen method and minimal basis set. For example, a small molecule consisting of atoms high in the periodic table may only incur small errors for most methods hence a fast, simple method with a small basis set may be sufficient. However it will be seen that for larger atoms, the errors are more important and larger basis sets and more complex quantum mechanical models with longer computing times may be necessary for better accuracy. After optimisation, a molecule is then ready for further analysis such as frequency, molecular orbital and natural bond orbital calculations: all of which provide deeper understanding of the bonding and reactivity of a compound.

The Optimisation of BH3

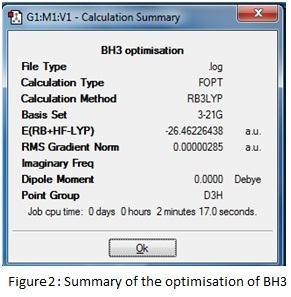

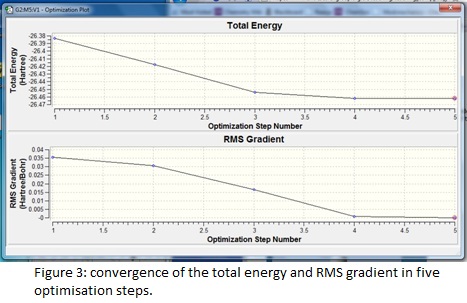

A trigonal planar molecule of BH3 was created and each bond length was set to 1.5 Å. Using the B3LYP method and the 3-21G basis set, this was optimised to a structure with all bond angles at 120o and all B-H lengths at 1.19 Å. A summary of the results is given below in figures 2 and 3. The log file can be accessed at: DOI:10042/to-6528 .

The summary reveals information about the molecule such as the dipole moment and point group as well as recording the details of the calculation; the short time taken reflects the simplicity of the chosen model and the RMS (root mean squared) gradient is much less than 0.001, which indicates the high level of accuracy achieved. The success and speed of the convergence is displayed in the graphs; only five steps were required to find the smallest gradient. This coincides with progressive contraction of the bond lengths which may be illustrated using snapshot images of each step in the calculation- in fact at 1.50 Å, the model cannot detect any bonding interactions between the boron and hydrogen atoms.

Molecular Orbitals of BH3

Using the optimised structure, it is possible to estimate the shapes and energies of the molecular orbitals of BH3. Below is the molecular orbital diagram based on the linear combination of boron atomic orbitals and the tri-hydrogen fragment.

Output (see checkpoint file) for the MO analysis: DOI:10042/to-6527

The LCAO method agrees well with the Gaussian calculation in that all of the MOs can be identified by matching regions of positive and negative phase and the positions of the nodes are in concordance. Most importantly, the HOMO can be seen clearly in both cases as one of two degenerate e' bonding orbitals and the LUMO is the empty non-bonding pz orbital. Two comparisons may be drawn between the two approaches: qualitatively the final computed MOs convey an appearance of higher delocalisation whereas in the simpler diagrams this must be imagined as the constructive overlap of in-phase atomic orbitals. Furthermore, the LCAO method requires further calculations in order to accurately predict the relative coefficients of each atomic orbital (i.e. the magnitude of their contribution) in the final MOs. This is exemplified in the more diffuse appearance of the unoccupied computed MOs in relation to the occupied orbitals; LCAO could no predict this. Quantitatively, it is also difficult to rationalise the relative energies and the size of the orbital splitting of the LCAO results; the diagram above shows the anti-bonding 3a'1 orbital to be lower in energy than the anti-bonding 2e' whereas the computational results report 3a'1 to be higher. In addition, numerical evidence of the orbital energies provides a more convincing argument for the lack of interaction of the low-lying boron 1s atomic orbital shown at the bottom of the diagram as non-bonding. This demonstrates that it is useful to sketch an MO diagram such as the one above in order to better understand the formation of the final MOs and as a general reference point but for greater accuracy and quantitative analysis, computational methods must be applied.

Natural Bond Orbitals of BH3

Natural Bond Orbitals are the intermediate of atomic and molecular orbital representations: they may help us to understand the partition of electron density between the nuclei of a 2c-2e bond. Figure 5 shows the BH3 molecule with an electron deficient (green) region at boron and electron rich (red) regions at each of the hydrogens. The output file (see corresponding log file of MO analysis above) reports these charges to be +0.33 and -0.11 respectively. The results also state that each B-H bond has 44.49% boron and 55.51% hydrogen contributions to the total electron density, which is in agreement with the approximate charge distribution. For the boron centre, this is comprised of 33% s character and 66% p, meaning that boron contributes to bonding via three sp2 hybridised orbitals. Each hydrogen has 100% s character, which is to be expected given that H atoms only have a 1s AO to contribute. Additional information such as the "lone pair" orbital with 100% p character centred on boron correlates well with the MO analysis in the previous section; this is the empty LUMO formed from the non-bonding pz orbital. The NBO analysis also detects the "core" bonding orbital with 100% s character on boron, which corresponds to the low energy boron 1s AO that could not be combined with the hydrogen fragment.

While LCAO may fail to recognise the effects of mixing interactions between MOs of similar energy and symmetry and computing these MOs may fail to explain their origin, NBO analysis makes it easier to identify these constructions. In the Secondary Order Perturbation Theory section of the results for BH3, there were no reports of significant mixing effects however for many other molecules this may be of high importance.

Vibrational Analysis

The optimised BH3 molecule was also subjected to frequency analysis in order to simulate the vibrational modes and IR spectrum as well as to confirm the success of the optimisation. This is necessary because the optimisation only involves finding points on the potential energy surface where the derivative (i.e. the forces) is zero. This could however be a maximum turning point (such as a transition state) and not the desired minimum energy, hence the second derivative must be determined to confirm the nature of the turning point: this is taken into account by frequency analysis. Each vibrational mode has a potential energy surface with the most stable structure at the minimum and so the curvature of the mode must always be positive. Any negative values (as long as they are not associated with errors at frequencies close to zero) must therefore be discarded and the optimisation must be re-visited.

The results of the frequency analysis may be found at: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/5/5a/NT208_BH3_FREQ.LOG

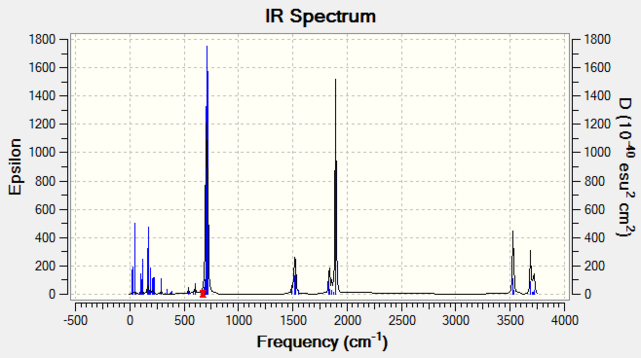

The total energy was identical to that of the optimisation, which is to be expected given that the same method and basis set were applied. Most importantly, this also means that no changes in the structure have occurred. BH3 like any other molecule has 3N-6 vibrational degrees of freedom where N denotes the number of atoms. The "-6" states appear in the results as modes very close to zero. These are due to motions about the centre of mass of the molecule and their magnitude is subject to inherent errors in the calculation: the better the approximation, the closer to zero these values will be. The largest "low frequency" was 22 cm-1; if a more rigorous method than B3LYP had been employed, this value would have been further minimised. Figure 6 shows the computed IR spectrum:

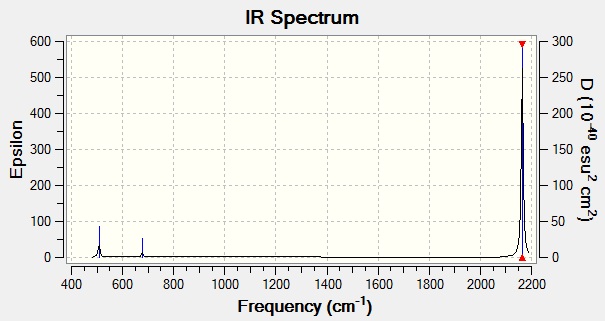

Figure 6

Figure 6

Only three modes are observed and this may be explained using the rules of infrared spectroscopy. For a mode to be "IR active", there must be a change in the dipole moment during the vibrational transition. Hence fully symmetric transitions such as a centrosymmetric bond stretching will be silent and not featured in the spectrum. The table below demonstrates the active modes for BH3:

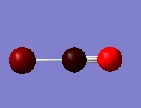

The Optimisation and Vibrational Analysis of TlBr3

The analysis of BH3 may be applied to larger molecules of the same point group. The following example involves TlBr3, which requires the application of a pseudo potential in order to better simulate the heavier atoms involved. This improves the approximation by taking into account the relativistic effects imposed on their distant valence electrons; it was not necessary for BH3 as it only features first row elements and these effects so minimal that the extra computing time would not be worthwhile. The chosen model was B3LYP with the medium basis set LanL2DZ. The point group symmetry was constrained to D3h and the tolerance was tightened to 0.0001 to impose strict rules for the convergence.

A summary of the optimisation showed that the RMS gradient converged to 9 x 10-7 a.u. and was therefore successful. The frequencies computed were all positive which further supports the discovery of the minimum energy structure. Information such as the equilibrium Tl-Br bond length and bond angle was obtained: these were 2.65 Å and 120o respectively. The literature value for the bond length was 2.512(2) Å[1] which is not too dissimilar to the computed value.

Figure 7: Computed IR spectrum of TlBr3

Figure 7: Computed IR spectrum of TlBr3

There is a large difference in the energies of the vibrations of BH3 and TlBr3. The bonds of BH3 are stronger because the atoms involved are smaller and have higher surface charge densities: this leads to higher energy and therefore higher frequency modes. The ordering of the out-of-plane bend also differs and is perhaps dependent on the size mis-match of the atoms, which is greater for thallium and bromine.

Optimisation: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/1/11/TLBR3_OPT_NT208.LOG

Frequency analysis: DOI:10042/to-6643

cis and trans Isomerism in [Mo(PCl3)2(CO)2]

The techniques applied so far may be used to compare structures of a similar nature such as stereoisomers. The higher degree of symmetry in a trans octahedral metal complex leads to fewer IR active modes and so different IR spectra will be seen in each case. The trans and cis complexes of [Mo(PCl3)2(CO)2] have been optimised firstly "loose" criteria with the B3LYP method and the LanL2MB pseudo-potential. The loose convergence requirement accounts for the fact that the limits imposed would otherwise be too stringent for the B3LYP calculation ever to reach them in this case. This was further improved using a slightly more complex pseudo-potential: LanL2DZ. The dihedral angles about the phosphorus atoms were also manually adjusted to the geometries shown below (see "tight opt") since the true minima are known to resemble these structures. A final optimisation was needed to refine the phosphorus centres; the basis set applied does not account for hypervalency and so an "extrabasis" function was added to the command to simulate the low-lying dAOs of phosphorus.

During the optimisation, the P-Cl bonds seem to disappear from the Gaussview structure; this does not mean that they cease to exist, but rather that they are outside the length thresholds which the software considers to define typical P-Cl bonding. This does not affect further calculations such as frequency analysis since the Cartesian positions of the atoms remain fixed in the data files and this is the most important information about the molecule. Such observations raise the question of how to define bonding: a suitable description would be that a chemical bond is the result of attractive forces between two atoms which stabilise their positions relative to one another in preference to their free states. This is certainly reflected in the constant re-positioning of the atoms of these complexes as they are subjected to variational analysis. Incidentally, it is worth noting that after the final optimisation, the bonds reappear.

The relative energies of the two isomers after each optimisation is given below (a.u. in hartrees):

| Molecule | trans loose | cis loose | trans tight | cis tight | trans final | cis final |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy/a.u. | -617.525 | -617.522 | -623.577 | -623.576 | -623.694 | -623.693 |

| Energy/kJmol-1 | -1621312 | -1621304 | -1637201 | -1637199 | -1637508 | -1637506 |

(NB: All energies reported have an approximate error of ± 10 kJmol-1.) In each case, the trans isomer is of lower energy which suggests it is thermodynamically more stable. This can be rationalised by the lower degree of steric hindrance in the molecule since the large PCl3 substituents are as far apart as they can be. When reported in hartrees, the difference between the two isomers seems subtle but when converted to kJmol-1 it is much more apparent: the difference between the final isomers is about 2 kJmol-1. Although this is still within the error limits, the trend is convincing. Furthermore, the differences in energy between each optimisation track the progress of the structural refinement as lower energy conformations are found each time the model was improved.

Some computed structural paramters were also obtained and compared with literature values:

| Computed trans | Lit.[2] | Computed cis< | Lit.[3] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P/Angstrom | 2.42 | 2.50 | 2.48 | 2.58 |

| Mo-C/Angstrom | 2.06 | 2.01 | 2.02 | 2.06 |

| P-Mo-P/degrees | 177 | 180 | 94 | 94.8 |

| C-Mo-C/degrees | 89 and 178 | 87 and 179 | 89 and 179 | 83 |

| C-Mo-P/degrees | 91 | 87 and 180 | 90 and 176 | 91.7 and 173.2 |

Where there were multiple parameter of the same type, an average result was taken. The results compare very well with the literature X-ray structures which supports the strength of the optimisation and the chosen model.

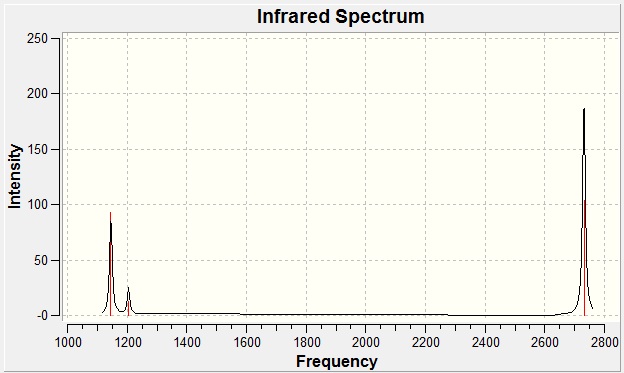

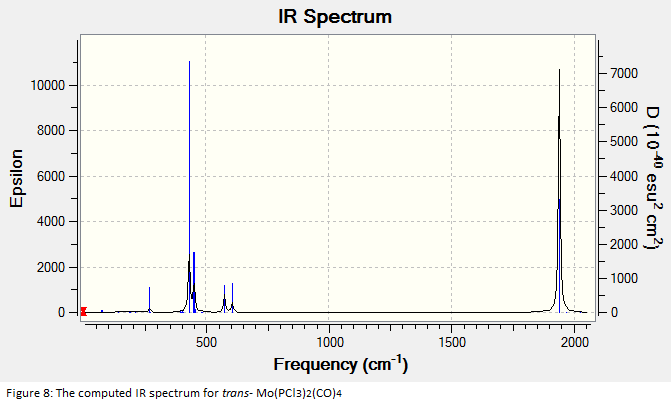

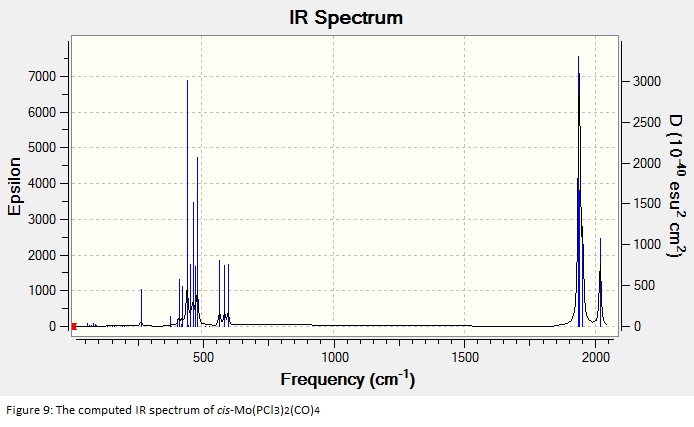

The final optimised structures were subjected to frequency analysis and the results are summarised in the spectra below:

All of the frequencies (except some very small low frequencies) were positive and so the minimum energy structures were established. The trans spectrum features one carbonyl stretch at 1939 cm-1 (lit[4]. value for trans-Mo(PPh3)2(CO)4: 1891cm-1) whereas the cis isomer shows four such stretches at 1938, 1942, 1952 and 2019 cm-1 (lit.[5]: 1897, 1908, 1927 and 2023cm-1). This is to be expected since the higher symmetry of the trans isomer renders some of the combined carbonyl stretches IR silent as they are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. There are in fact two degenerate, asymmetric stretches as shown in the figures below. In the cis isomer, each carbonyl sits in a different environment with respect to the others and so four distinct modes are seen. They may both differ largely from literature values not only because the phenyl groups have been substituted for chlorine but because the practical results are measured in solvent and these computational techniques assume a gas phase environment. The most important result is the number of stretches.

| Wavenumber/cm-1 | 1939 | 1939 |

|---|---|---|

| Vibration |  |

|

| Wavenumber/cm-1 | 1938 | 1942 | 1952 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vibration |  |

|

|

|

Trans loose optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6644

Cis loose optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6645

Trans tight optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6646

Cis tight optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6647

Trans final optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6648

Cis final optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6649

Trans frequency analysis: DOI:10042/to-6931

Cis frequency analysis: DOI:10042/to-6940

Mini-Project: Linkage Isomerism in [Co(SCN)(NH3)5]2+

Ambidentate ligands such as thiocyanate give rise to linkage isomers which often exhibit very different properties. The pentaammine cobalt(III) complex under investigation may form a violet thiocyanate or an orange isothiocyanate structure; the resultant products interconvert (from -SCN to -NCS) at low pH with NaClO4 present[6]. Other studies have assigned predictions of the preferred mode of binding to hard and soft acid/base theory: nitrogen is described as a "hard donor" and sulphur is the "soft donor"[7]. Vibrational, MO and NBO analysis may be applied to further distinguish the molecules and computational techniques can be applied to further understand the nature of the bonding in each case, with respect to that of the free SCN- ligand.

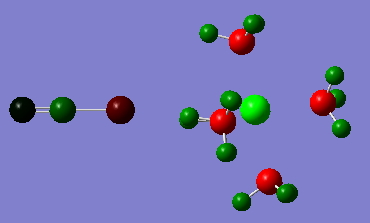

SCN-

The SCN- ligand was optimised using the B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set, which was deemed sufficient given the small size of the molecule. The dAOs of sulphur may be included to improve the model but these would be too high in energy to interact much with the valence electrons of the cyanide ion. Particular attention was needed to set the charge of the molecule to -1 and the multiplicity as a singlet. The energy computed was -488.622 a.u. (-875.089 kJmol-1) with an RMS gradient of 0.00020452 a.u. The bond lengths were reported: S-C was 1.72 Å and C≡N was 1.18 Å (literature values: 1.64 ± 1.6 Å and 1.161 ± 0.9 Å)[8].

This was then subjected to frequency analysis to give the following vibrational spectrum:

Figure 10

Figure 10

The three atoms of SCN- give rise to 3N-5 vibrational modes since the molecule is linear. All of these are IR active due to the low degree of symmetry perpendicular to the principal axis (along the bonds). The energies and intensities quoted in the table will be used as a reference for comparison with data from the bound SCN- ligand.

The MOs of SCN- were then computed. They compare very well with an LCAO analysis as shown in figure 11. They will be used later on to investigate the two modes of thiocyanate binding to a metal centre.

The NBO analysis of SCN- shows that the entire molecule shares the high density of charge but the carbon is almost neutral and the nitrogen atom bears most of this, which is not surprising since it is the most electronegative atom. The calculated charges were -0.28, 0.11 and -0.61 for S, C and N respectively. This reflects upon the suggestions proposed earlier that nitrogen is a hard donor and sulphur is a softer donor.

Figure 12.

The breakdown of the NBOs is as follows:

- The S-C bond has one component of 42% sulphur and 58% carbon contributions. Of this the sulphur has 16:84 s:p character and the carbon has an sp ratio of roughly 53:47. So this may be considered as the sigma overlap of a p-orbital with an sp-hybridised orbital on carbon.

- The CN bond has three components; the first is 41% carbon and 52% nitrogen, with a 46:54 sp carbon and a 48:52 sp nitrogen. This is also therefore a sigma overlap. The second and third each have 45% carbon to 55% nitrogen contributions both comprised of 100% p-type character. These complete the expected triple bond as orthogonal pi-overlapping.

- Other notable NBOs were two core s-type and three core p-type orbitals on sulphur; the MO analysis also detected these as too low in energy to interact. They refer to the 2s, 2p and 3s AOs.

- Three lone pairs were reported on sulphur; two are p-type and one is s-type (estimated as 85:15 s:p character). One lone pair was seen on nitrogen and recorded as sp-hybridised (53:47 s:p). These were not so obvious from the MO analysis but may be derived from a Lewis structure of SCN-.

Overall this provides a breakdown of the bonding and electron density of the molecule: the single S-C bond and triple C≡N bond can be understood as the result of contributions from the valence 3p-orbitals of sulphur, the two sp and two p-orbitals of carbon and an sp and two p-orbitals from nitrogen. This corresponds with the MO approach in that the overall S-CN bonding picture is summarised by one valence sigma interaction and two valence pi-interactions.

Optimisation log file: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/a/a3/SCN_OPT2.LOG

Frequency analysis: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/5/5f/SCN_FREQ2.LOG

Molecular and natural bond orbital results: DOI:10042/to-6761

Thiocyanate Isomer

The first optimisation was carried out using the B3LYP method and the LanL2MB basis set with loose convergence criteria. The charge was set as 2+ and the quintet multiplicity was rationalised using the d6-occupancy of Co(III) and assumption that the complex is high spin (thiocyanate is low in the spectrochemical series and NH3 is of medium field strength- hence the octahedral splitting parameter is expected to be small). This took 78 steps and the energy reported was -525.499 a.u. (-1379697 kJmol-1 with an RMS gradient of 0.00004015 a.u. This was followed by the LanL2DZ as an improvement to the pseudo-potential: switching to the GEN basis set allowed for custom adjustments to the heavier atoms, sulphur and cobalt, only. However the calculation failed to converge and the reason behind this is unclear at this stage. Subsequent analysis was performed on the loosely optimised structure and the results are therefore less accurate than desired.

Link to the first optimisation: DOI:10042/to-6863

The S-C bond length was 1.72 Å and C-N was 1.24 Å. These are much longer than the bonds featured in the free ligand and show a reduction in bond order. The natural bond orbital analysis showed only very small distortions in the atomic contributions and bonding character so it was concluded that the ligand had retained its S-C sigma bond and its triple C≡N bond. More noticeable effects are associated with the charge of the ligand as shown in figure 13:

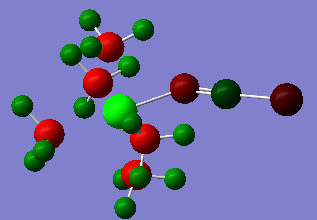

Figure 13

Figure 13

The cobalt forms a region of high positive charge and so the thiocyanate charge is greatly reduced. The sulphur atom is now only very weakly negative and the nitrogen atom only slightly more so.

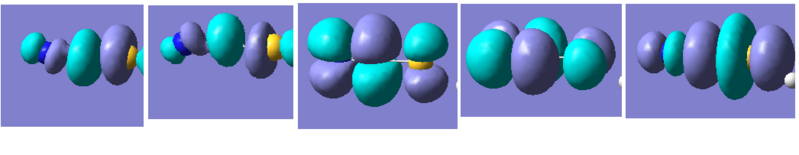

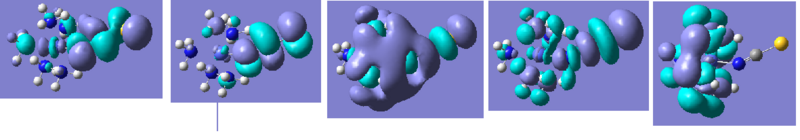

The MO analysis supports these results. As figure 14 shows, there has been very little effect on the shapes of the ligand MOs upon coordination:

Figure 14

Figure 14

These correspond to the five molecular orbitals leading up to the HOMO (far right). The LUMO does not support any bonding interactions across SCN. Overall, a hypothesis can be made that the coordination of a thiocyanate ligand to a cobalt metal centre is largely built on ionic interactions rather than covalent binding since the charges rather than the orbitals were more significantly perturbed.

NBO and MO analysis:DOI:10042/to-7023

Figure 15 (right) shows the computed IR spectrum for the thiocyanate complex. The main results are as follows: the SC stretch was at 674 cm-1 and the CN stretch was 1895 cm-1. This similarity with the free ligand indicates very minor effects on the SC bond. The decrease in CN stretching frequency is in keeping with a weaker bond, which is intuitive given that some of the electron density has been drawn away by coordination to the metal.

Vibrational analysis:DOI:10042/to-7032

Isothiocyanate Isomer

The first attempt at a loose optimisation for this structure with the same criteria as the thiocyanate isomer failed to converge (the output file for this is given below). The possibility that the multiplicity of the metal centre could different was considered; if the cobalt is d6 low spin in this case then the multiplicity must be set as a singlet. This is highly likely given that the second attempt fully converged:

First attempt: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/3/3f/Failed_NCS_linked_loose_opt.txt

Second attempt: DOI:10042/to-6919

The energy of this isomer was almost exactly the same as that of the thiocyanate isomer: -525.558 a.u. (-1379852 kJmol-1 and the RMS gradient was 0.00006842 a.u. This translates to about 150 kJmol-1 greater stabilisation for an isothiocyanate linkage isomer. This may be rationalised by studying the outputs of the NBO and MO calculations. The computed SC bond length was 1.74 Å and the CN bond was 1.23 Å: these are almost identical to those found for the thiocyanate isomer. The largest difference is the metal-ligand bond which was much shorter at 1.90 Å. The metal-ligand bond angle was not 180o as seen before but 134o, which is indicative of a change in the hybridisation of the bound nitrogen atom.

The NBO analysis shows a similar charge distortion to that of the bound thiocyanate ligand; nitrogen is the most negative atom, but only slightly more than the sulphur atom, which is close to neutral.

Figure 15

Figure 15

A breakdown of the bonding character is more interesting this time. There are reported covalent interactions between nitrogen and cobalt and to compensate for this, much higher degrees of s-type character in the N-C bond. For example, two of the components show roughly 30:70 s:p ratios which indicates a slight change at nitrogen, moving from sp to sp2. This is complemented by loss of the sp lone pair on nitrogen as seen in the results for the free ligand.

Figure 16 above illustrates the shapes of the MOs. They are the corresponding five MOs to those described in the thiocyanate section (the HOMO is on the far right). This time the HOMO features no orbital density on the ligand, which makes it a more stable area of the molecule and the MOs just below this in energy have larger regions of smeared charge across the molecule. Overall there are more covalent interactions between nitrogen and cobalt than between sulphur and cobalt; if HSAB theory is revisited, this may indicate that Co(III) is a hard acid and prefers binding to nitrogen (the hard base). This also supports the higher degree of bonding seen in the complex and the larger distortions on the ligand.

NBO and MO analysis:DOI:10042/to-7028

Figure 17 is the computed iosthiocyanate isomer spectrum. The SC stretch is at 785 cm-1 and the CN stretch is at 2000 cm-1. This corresponds to a increase in SC bond strength and a decrease in CN bond strength. The latter effect was supported by MO and NBO analysis but further optimisation would be required to understand the effects on the sulphur-carbon bond. It may be perhaps more useful to describe this as a decrease in bond order rather than simply stating a decrease in bond strength as it cannot be rationalised as a difference in bond length from the CN bond of the thiocyanate isomer.

Vibrational analysis:DOI:10042/to-7034

References

- ↑ J. Glaser and G. Johansson, Acta. Chem. Scand. A., 1982, 36, 126.

- ↑ Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171.

- ↑ Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294-299.

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14.

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2681.

- ↑ D. A. Buckingham, I. I. Creaser and A. M. Sargeson, Inorg. Chem., 1970, 9, 655–661.DOI:10.1021/ic50085a044

- ↑ R. G. Pearson, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1963, 85, 3533.

- ↑ R. Loos, S. Kobayashi and H. Mayr, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2003, 125, 14126–14132 DOI:10.1021/ja037317u .