Rep:Mod:7bris

Module 2 - Inorganic Computational Chemistry

Introduction to Module 2: Finding out about BCl3

Using the GaussView program the BCl3 molecule was optimised using a B3LYP/LANL2MB method and the tabulated data was obtained. The LANL2MB basis set was suitable for our purposes because it is a 'medium level' basis set and so the calculation will not take too long. Also, the symmetry of the BCl3 molecule was constrained to D3h so that later vibrational calculations would be facilitated if they were to be carried out.

Finding Out about Small Molecules

In order to practice optimisation methods, information from two small molecules were extracted. A b3lyp/3-21G method was used. This basic basis set roughly approximates the energy. The molecules were optimised in Gaussian and the resulting outputs are saved in d-space.

|

| |

| x,y,z coordinates | C (0, 0, 0), O1 (0, 0, 1.2), O2 (0, 0, -1.2) | S (0, 0, 0.1), H1 (0, 1, -0.8), H2 (0, -1, -0.8) |

| C-O/S-H bond length | 1.183Å (lit. 1.163Å) | 1.374Å (lit. 1.336Å) |

| Bond angle | 180° | 93.8° (lit. 92.1°) |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| Final Energy (au) | -187.52 | -397.41 |

| Dipole Moment | 0 debye | 1.7831 debye (lit. 0.97D) |

| Point Group | D∞H | C2V |

| Length of Calculation | 1 minutes, 50.3 seconds | 2 minutes, 13.8 seconds |

The calculated properties of the small molecules are compared against their literature values (taken from wikipedia). Due to the rough approximation used to optimise the molecules, there is quite a lot of error between calculated and actual data values. The 3-21G basis set has not taken into account enough electronic interactions. If a higher approximation was used e.g. 6-31G, then the calculated values would be closer in value to the actual.

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The frequency was obtained through GaussView. The total energy of the resulting molecule is the same as the optimised molecule which means the structures are uniform.

The IR of BH3 is shown (left). There are only 3 peaks in the spectrum although there were 6 vibrational modes. This is due to the degeneracy of 2x2 of the modes (Modes 2, 3 and 4, 5) and the zero intensity of vibrational mode number 4. There is zero intensity for this mode of vibration because the net change in dipole is zero for the vibration. In order that a vibrational mode has an absorbtion in IR, it must have a dipole moment.

The Molecular Orbitals of BH3

The .log file for the previous calculation was altered so that the coordinates matches those expected with a D3H molecule, thus the MO's could be calculated. The aim was to compare the predicted MO's with those calcuated and thus validate the accuracy and usefulnes of the qualitative MO theory. The diagram shown right was created in ChemDraw with help from 2nd year MO Theory lectures.

I think the approximation that the qualitative MO theory offers us is excellent. There is excellent correlation between the diagram and the calculated MOs. However, for a more complex molecule, the approximation may not be as good.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Optimisation and Vibrational Modes of Mo(CO)4(pip)2

The cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(pip)2 were studied in order to view the CO stretching frequencies in each isomer. The complexes were optimised first with a b3lyp/LANL3MB method, then with a more accurate b3lyp/LANL2DZ method:

# opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity int=ultrafine scf=conver=9

The DZ basis set is a much better pseudo-potential basis set for approximating complexes. We will see it used also in the Mini Project later on.

| 'cis'-tetracarbonylbis(piperidine)molybdenum (0) D-space view | 'trans'-tetracarbonylbis(piperidine)molybdenum (0) D-space view | |

|

| |

|

| |

| Calculated Vibrational modes (cm-1) | 411, 606, 656, 806, 871, 1005, 1048, 1520, 1827 (B2), 1841 (B1), 1853 (A1), 1962 (A1), 3032, 3074, 3097, 3146 | 415, 588, 668, 873, 1010, 1054, 1512, 1814 (B2), 1815 (B1), 3030, 3094, 3146 |

| Experimental CO Vibrational Modes (cm-1) | 1778, 1840, 1890, 2012 | ~1888, ~2013 |

| Point Group | C2v | D4h |

|

| |

| Mo-N bond length | 2.42207Å (lit. 2.317Å, 2.342Å (Mo-N) and 1.7391Å (Mo=N) [1] [2] | 2.36208Å |

IR assignments in bold are the CO stretching frequencies.

There are 100s of vibrational modes listed in the output file, so the ones listed from the calculation are those shown in the spectra (i.e. IR intensity>50). The CO stretches are those shown in italics. IR studies of CO streches are a good indicator of the nature of the other ligands around the metal centre and their electron donating/receiving characteristics. The CO stretches shown have been assigned a vibrational mode from the point group. I looked at literature values for sigma and pi bond lengths for Mo-N bonds and from this we can see that Mo-N bonds are most like sigma bonds than double bonds i.e. there is no backbonding from the Mo metal centre into the Mo-N bond. This is due to strong inductive CO ligands pulling electron density from the metal centre.

The energy difference between the two isomers is ΔEcis/trans=-40kJ/mol. Suprisingly the most stable isomer is the cis-isomer. This is suprising because the cis-isomer has an unfavorable large dipole, steric clash between the (pip) ligands and the cis- isomer is less symmetric. On the other hand, the Mo-N bond length is longer in the cis- case which could be energetically favourable.

Perhaps for a catalytic cycle involving this complex we require the trans- isomer only so we would need the trans isomer to be more energetically favourable. If this is the case, the (pip) ligands could be altered in order to lower the energy of the trans- isomer. Electron withdrawing substituents could be added to the piperidine ring so that electron density from the metal is drawn into the Mo-N antibonding orbital, thus lengthening the bond. If I had time I could test this theory using similar techniques already implemented in this exercise.

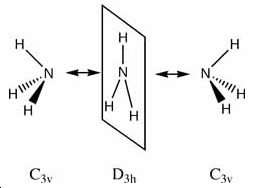

The Quantum Nature of Ammonia

The inversion of ammonia is achieved by the tunnelling of hydrogen atoms from one side of the nitrogen to the other i.e. from "left" to "right". This tunnelling occurs several times a second and there exists a small potential barrier between the two forms as a stationary state exists between the two inversions. The inversion causes inversion doubling of the vibrational modes. The quantum levels of "left" and right" inversion can then be used in quantum computers instead of the usual 1 and 0 notation used in electron computing.

First we will look at the symmetry of the inversion of ammonia.

Low Level Optimisation of Ammonia

It is interesting to note from the summaries, the further down the symmetry sub group the molecules are (C1-C3v-D3h) the shorter time the calculation takes. This is because high symmetry molecules are more easily optimised due to less conformations which allow the symmetry to be maintained. However, high symmetry molecules can undergo breaking of symmetry if a particularly low energy conformation is found that is of lower symmetry. This can be done by changing bond length or bond angles as we did with the bond modification. This shows that breaking the symmetry does give a lower energy result. From our 3 calcualtions with ammonia, the lowest energy geometry is the trigonal pyramid with the bond modification i.e. the C1 point group. (The highest energy geometry is trigonal planar with the highest symmetry.) The energy difference between the trigonal pyramidal geometry and the planar state shows us there is a potential energy barrier of ≈0.91 kJ/mol between the two inverted states of ammonia. The difference in energy between the trigonal pyramid and the symmetry broken trigonal pyramid is not too significant because the non-symmetry broken geometry does not feel the energetic need to break symmetry to minimise further it's energy by lengthening it's bonds.

High Level Optimisation of Ammonia

A higher level 6-311G+(d,p) basis set and the MP2/B3LYP method were used in order to achieve the ground state and transition state. The optimised molecules are shown left as thumbnails. The upper image is the ground state of ammonia in it's trigonal pyramid geometry and the lower is the planar transition state. The potential energy barrier between these two states has been calculated as 20.5 kJ/mol (expt. 24.3 kJ/mol). This difference in energy could be due to inaccuracies in the high level calculation used. Further approximations could be done to optimise the energies of both states. Compared to the lower level optimisation (B3LYP/6-31G) there has been a 10-fold increase in the energy barrier due to the more accurate method used.

Similarly to the lower level optimisation, the higher symmetry calculation takes less time to run. However in higher level calculations, the C3V optimisation takes longer (+6s) with the high level optimisation, but the D3h takes less time (-7s) than the lower level calculations.

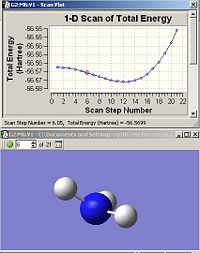

The Reaction Path of the Inversion Process

We have looked at the D3h and C3v state and now we want to look at how the two states interconvert. By using a 'scan' method, we can fix the nitrogen atom while the hydrogen atoms invert like an umbrella. The output file run in GaussView makes a 'movie' of the inversion of the ammonia.

The Vibrational Modes of Ammonia

Using the B3LYP/6-31G optimised structures of the C3v and D3h geometries of ammonia the frequencies of each geometry were calculated. Each frequency was assigned a vibrational mode according to the point group.

| C3v | D3h |

|---|---|

| ν(cm-1) 832 (A1), 1642 (E), 1642 (E), 3663 (A1), 3821 (E), 3821 (E) | ν(cm-1) -359 (Aˡˡ2), 1636 (Eˡ), 1636 (Eˡ), 3662 (Aˡ1), 3883 (Eˡ), 3883 (Eˡ) |

| ν lit. [3](cm-1) 933, 968.3, 1626, 1627, 3336, 3337, 3344, 3344 |

The C3v point group has 6 positive frequencies: 2x2 degenerate modes and 2 non-degenerate modes. The D3h point group has 5 positive frequencies: 2x2 degenerate modes and 1 non-degenerate mode. One frequency is negative (-359cm-1) which relates to the transition state of this geometry. In both geometries there is one particular vibration which 'follows' the inversion reaction path.In C3v, the A1 vibration (ν = 832 cm-1)is similar to the inversion process and in the D3h geometry the Aˈˈ2 vibration (ν = -359 cm-1)is the same.

It is not only these vibrations which have similar modes in each geometry. In fact, all the vibrations match up with another vibration in the other geometry:

| C3v | D3h |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mini Project: The Stability of Four Inorganic Dyes

I have "been commissioned" by the V&A museum to use computational techniques in order to find out why certain dyes used in wall hangings and tapestries have discoloured quicker than others. The tapestry shown left is a classic example of a 15th Century wall hanging. It is part of a series known as The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries[4]. They were made for Bess of Hardwick, who was a very wealthy widow in the 17th Century. The tapestries, however, are 15th century and as you can see with this example and with most tapestries of the era (unless they have been kept in the dark all this time), the blue dye stays fast to the woolen tapestry whereas the red dye has sadly faded from light and air exposure. In this mini-project I will look at 4 different inorganic dyes and find out why the stability of dyes are so varied[5] and what feature of these dyes aids or hinders their steadfastness. I will study a range ancient and modern dyes. The four dyes I will study are Aurolin, Alizarin, Phthalocyanine and Purpurin.

Aliarin and Purpurin dyes are common mordant dyes dervived from the madder plant.[6] They are aromatic organic molecules coordinated to an Aluminium centre (the mordant)[7]. Without this mordant the colour would not fast to the wool of the tapestry. Madder was used by Ancient Civilisations [8]to decorate pottery, walls and to dye cloth. In it's organic, non-mordanted form it can keep it's colour but when it is fast to wool, the complex breaks down and the organic solid left on the surface of the material to be dispersed in air. We still see red colours on Ancient artefacts due to the use of animal glues to 'stick' the solid to the surface of the pot.

Aureolin (or Cobalt Yellow) is a much more recent dye. It was discovered in 1843 [9] by N.W. Fischer and became a popular, yet expensive, pigment used in oil paints and watercolours. This fact means that the compound is unlikely to be affected by hydration or oxidation over time. This will be confirmed in the results.

Finally, Phthalocyanine Blue was developed in the 1930's as a lightfast dye. It consists of a phthalocyanine molecule complexed to a central Cu2+ ion. The phthalocyanine molecule is planar and aromatic when complexed but can be oxidised up to a non-aromatic, non-planar compound.

The stability of the four dyes will be measured by comparing the energy of the dyes with possible decomposition products. The dyes will be subject to degredation by oxygen, pollutants, water vapour, heat and light. I will concentrate on the effect of water vapour and also separation of the complex to it's ligand and metal substituents.

All molecules were optimised using a b3lyp/LANL2MB method followed by a b3lyp/LANL2DZ method to increase electronic convergence and improve the approximation. The same method was used for all molecules because you cannot compare the energies for molecules optimised by different methods.

Results from Stability Studies

| Purpurin dye | Phthalocyanine dye | Alizarin dye | Aureolin dye | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour/Max. Absorption | Pink/red 515nm[10] | Purple/Blue 544nm, 418nm [11] | Orange/red 430nm | Bright Yellow 540nm (Fluorescence spectrum)[12] |

| b3lyp/LANL2DX Optimised Structure |  |

|

|

|

| Summary page for LANL2DX Optimisation |  |

|

|

|

| D-space view of LANL2DX optimised structure | Purpurin | Phthalocyanine | Alizarin Only optimised to a LANL2MB level due to problems with the 1st optimisation calculation | Aurolin |

| Possible degredation products | 3xpurpurin molecules + Al or Al(OH)3 | Phthalocyanine + Cu or Cu(H2O)6 | Alizarin + Al or Al(OH)3 | 6 x NO2 + Co or Co((H2O)6 |

| ΔE (degredation products-reactants) | ΔE(purpurin +Al - purpurin dye) = -629594 kJ/mol | ΔE(Phthalocyanine +Cu - Phthalocyanine dye) = -5473 kJ/mol | ΔE(Alizarin +Al - Alizarin dye) = -593040 kJ/mol | ΔE(6NO2 + Co - Aurolin dye) = +2590604 kJ/mol |

| ΔE (hydrated products-reactants) | ΔE(purpurin +Al(OH)3 - purpurin dye) = -1227171 kJ/mol | ΔE(Phthalocyanine +Cu(H2O)6 - Phthalocyanine dye) = -1163881 kJ/mol | ΔE(Alizarin +Al(OH)3 - Alizarin dye) = -1145724 kJ/mol | ΔE(6NO2+Co(OH)6 - aurolin dye) = 1431941.667 kJ/mol |

Conclusions for Stability Study

It is very important to stress that the energies calculated are to be taken as relative energies and compared qualitatively and not as exact figures. We are not able to find out how fast each dye will decompose but we can compare between dyes and see which parts of the tapestry will fade first.

Firstly we will look at the madder-based dyes: purpurin and alizarin. Both products would decompose quite readily due to the energetic gain from decomposition. It is twice as favourable for the madder-based dyes to decompose to the hydrated products. This could be due to the affinty of the dyes to water due to hydrogen bonding of the ligands which contain -OH groups. These groups would also be used to hydrogen bond to the wool fibres but if water was present, either hydrogen bond could form. However, we do not know for sure that Al(OH)3 would be formed as a hydration product as no studies have been done on the hydration of madder-mordant dyes. We can confirm that the ligand-Al bond would be broken thus freeing the ligand. The breaking of the Al-madder dye bond means that the red colour is no longer bonded to the wool. The red colour would not fade until the purpurin/alizarin solid was dispered in air.[13]

The blue/purple dye Phthalacyanine is noticably more stable than the madder-based dyes due to it's lower Estab on decomposition. It must be noted however that this dye will keep it's colour if it decomposes into it's substituents (i.e. not hydrated). This was investigated in Y2 Synthesis Laboratory [14]. This could explain the longevity of the colour when used in art.

Cobalt yellow was expected to be stable in water and indeed our prediction is correct. The aurolin dye is the most stable out of all the dyes calculated. The positive Estab shows us that it will not decompose into it's products. This explains the longevity of the dye in modern art, but time will tell how long it's colour will last as it is a relatively modern colour. The action of light, O2 and other pollutants may react with aurolin and cause degredation of colour.

From our studies we have confirmed using computational methods that red areas of tapestries would fade first due to the decomposition of the Al-madder bond and dispersion of the dye. We have not studies the degredation of colour by 3O2 or light. This would bring up complex radical mechanisms which would require more time to work out and calculate. If given more time, I would like to investigate the relative stabilities of more natural dyes, like Shellfish Purple and Orchil from lichens.

References

- ↑ Mo-N bond length DOI:10.1007/s10870-005-5839-8 DOI:10.1016/0022-328X(91)80263-J

- ↑ Mo=N double bond DOI:10.1007/s11243-004-9171-5

- ↑ W. Zheng, Chemical Physics Letters 440 (2007) 229–234 DOI:10.1016/j.cplett.2007.04.070

- ↑ George Wingfield Digby, The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries (HMSO, 1971)

- ↑ Brommelle, N.S. , Studies in conservation, 9, 4 (1964) 140-157

- ↑ C. Miliani, Spectrochimica Acta Part A 54 (1998) 581–588 DOI:10.1016/S1386-1425(97)00240-0

- ↑ Sheng Yong Chai, Thin Solid Films 479 (2005) 282– 287 DOI:10.1016/j.tsf.2004.11.182

- ↑ J. Sanyova, Journal of Cultural Heritage 7 (2006) 229–235 DOI:10.1016/j.culher.2006.06.003

- ↑ J. G. Bearn, The Chemistry of Paints, Pigments and Varnishes, London, 1932

- ↑ Ch-H Fischer, Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies, 13, 2, 319-331 DOI:10.1080/01483919008049546

- ↑ B.D.Berezin, Coordination Compounds of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines

- ↑ T. Miyoshi, Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 21 (1982) pp. 1032-1036 DOI:10.1143/JJAP.21.1032

- ↑ Vincent Daniels, Lecture Notes: Dyes and Pigments Part 1 Dyes, Royal College of Art/V&A

- ↑ Y2 Synthesis Lab, Spring term, Experiment 2, 2007