Rep:Mod:7521

Introduction - Week 1

Technological advances in recent years has opened up the world of computational chemistry to modelling many aspects of organic structure and reactivity. It no longer serves as a tool to only rationalise arguments for particular theories or the outcomes of reactions, but instead can now be used to predict new types of reactions as well as modifications to existing ones.

This module aims to illustrate some of the useful techniques involved in molecular modelling such as: using molecular mechanics to predict the geometry and regioselectivity of cyclopentadiene dimer and the stability of two atropisomers of a taxol precursor; using semi-empirical and DFT MO theory to investigate neighbouring group participation of a chloro-substituted bicyclic diene; modelling the mechanism of glycosidation of a monosaccharide.

In addition, a mini-project will be undertaken in the latter part of this module, which entails simulating spectroscopic data for a molecule in the literature which has two isomers or more. A comparison will then be drawn between the literature and the simulated data.

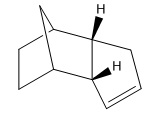

Investigating the cyclopentadiene dimer

Exo vs. Endo

Cyclopentadiene dimer exists in two forms, the endo- and the exo- form. Both products predominate under different reaction conditions and the analysis below will attempt to rationalise this.

Exo

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Note: All parameters used are finalized (Quality = 4). Iteration 76: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 1.2855 Bend: 20.5794 Stretch-Bend: -0.8381 Torsion: 7.6571 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.4171 1,4 VDW: 4.2322 Dipole/Dipole: 0.3776 Total Energy: 31.8766 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------------

Endo

------MM2 Minimization------------ Note: All parameters used are finalized (Quality = 4). Iteration 93: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 1.2507 Bend: 20.8476 Stretch-Bend: -0.8358 Torsion: 9.5109 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.5430 1,4 VDW: 4.3195 Dipole/Dipole: 0.4476 Total Energy: 33.9975 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

A comparison of the two energies can be drawn since they were computed using the force same field (MM2). Clearly, the exo conformation is lower in total energy than the endo confirmation by 2.1209 kcal/mol, which initially, may indicate a preference for the exo form since it is more stable. However, a quick comparison of the individual contributing energies to each conformation reveals that a significant contributor to the differing energies is that arising from torsion, accounting for 87.4% of the difference. This torsional strain relates to the C-C-C-C bond involved in joining the two rings. Hence, while, the exo form by be preferred thermodynamically, the endo form is favoured kinetically. A brief scan of the literature confirms this.[1]The exo conformation is preferred thermodynamically since their is less destabilisation due to repulsion of the various C-H σ orbitals. The endo form is assisted via the presence of attractive Salem/Houk secondary orbital interactions found in the transition structure.[2]

Hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer

The endo-cyclopentadiene dimer can be hydrogenated, with two alternative products resulting. These are shown as conformations 3 and 4 below. Again, using the MM2 force field, an attempt will be made to predict the favoured product.

Conformation 3

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Note: All parameters used are finalized (Quality = 4). Iteration 73: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 1.2490 Bend: 19.1569 Stretch-Bend: -0.8354 Torsion: 11.0764 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.6412 1,4 VDW: 5.7965 Dipole/Dipole: 0.1622 Total Energy: 34.9643 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

Conformation 4

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Note: All parameters used are finalized (Quality = 4). Iteration 75: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 1.1300 Bend: 13.0132 Stretch-Bend: -0.5653 Torsion: 12.4121 Non-1,4 VDW: -1.3246 1,4 VDW: 4.4411 Dipole/Dipole: 0.1410 Total Energy: 29.2475 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

Conformation 4 is clearly the more stable one by 5.7168 kcal/mol. A comparison of the relative energy contributions reveals that the major factor is the bend energy. A possible suggestion for this is that in conformation 3, the location of the sp2 alkene, usually a bond angle of 120°, is forced to 107.8° in conformation 3 and 112.4° in conformation 4. This exhibits restrictive strain on the molecule due to its proximity to the bridging carbon. On the contrary, it can be more easily accommodated in the location in conformation 4, hence it is lower in energy.

Atropisomers are stereoisomers resulting from hindered rotation about single bonds where the steric strain barrier to rotation is high enough to allow isolation of the conformers. Using the MM2 force-field, the two atropisomers of the Taxol precursor (carbonyl group "up", conformation 9, and "down", conformation 10) were optimised and a minimum energy calculated for each. A comparison of the energies with the MMFF94 force field is also made later.

Conformation 9

Taxol confirmation 9 |

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Warning: Some parameters are guessed (Quality = 1). Iteration 2: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 2.6023 Bend: 10.4205 Stretch-Bend: 0.2911 Torsion: 19.3695 Non-1,4 VDW: -2.2144 1,4 VDW: 12.9214 Dipole/Dipole: -2.0094 Total Energy: 41.3808 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

Conformation 10

Taxol confirmation 10 |

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Warning: Some parameters are guessed (Quality = 1). Iteration 287: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 2.5513 Bend: 11.3748 Stretch-Bend: 0.3201 Torsion: 17.3628 Non-1,4 VDW: -2.2619 1,4 VDW: 12.7427 Dipole/Dipole: -1.6998 Total Energy: 40.3901 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

From the calculations it can be seem that conformation 9 where the carbonyl group points up is the higher energy conformer. A direct consequence of this is that this is the more reactive conformer. This is confirmed in the MMFF94 calculations shown later.

The alkene in this Taxol precursor is particularly unreactive due to it being connected to a bridgehead carbon which violates "Bredt's Rule"[3], known as an anti-Bredt alkene.[4] This results in the alkene behaving more like a single bond due to the steric strain imposed on the sp2 carbon atom, reducing the reactivity of the alkene. The p oribtals of the bridgehead carbon are not aligned correctly for pi bonds due to the strain, hence, this type of alkene reacts slowly.

In 1950, Fawcett et al. formulated a more general rule to accommodate for the occurence of bridgehead alkenes, known as the "Fawcett Rule". This states that for a bicyclo[x,y,z]alkene, the sum of x + y + z must be greater than or equal to 9. (x,y,z represent the number of bridging atoms in descending order).[5] In the case of this taxol precursor, it is a bicyclo[10,2,1]alkene and hence the sum of the bridging atoms is 13, meaning it is an allowed alkene under Fawcett's rule.

Comparison of MM2 vs. MMFF94 on the minimised energy of a Taxol precursor

| Conformation | Method | Energy(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| 9 | MM2 | 41.3808 |

| MMFF94 | 61.198 | |

| 10 | MM2 | 40.3901 |

| MMFF94 | 60.6444 |

Although the energies between different force fields cannot be compared, we can, however, compare the relative energies of the two conformers calculated using the same force field. Both the MM2 and MMFF94 force fields concur that the more stable form in each case is conformation 9 where the carbonyl group is aligned "down".

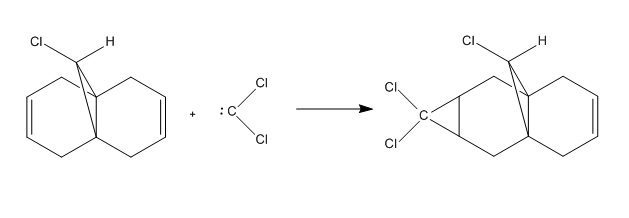

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene to a diene

This section of the module explores the electronic aspects of reactivity, showing how explicit consideration of the electrons in molecules must be taken into account. The following reaction is used to explore this.

| Method | Energy(kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| MM2 | 17.8946 |

| MOPAC | 22.82806 |

| Bond | MM2 | MOPAC |

|---|---|---|

| C(4)-C(5) | 1.503 | 1.488 |

| C(5)-C(6) | 1.523 | 1.509 |

| C(8)=C(9) | 1.339 | 1.328 |

| C(3)=C(4) | 1.340 | 1.330 |

| C(11)-Cl(12) | 1.760 | 1.782 |

| Superimposed image | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Atoms | Actual(°/Å) | |||

| C(33)-C(9) | 0.1001 | |||

| C(26)-C(1) | 0.0931 | |||

| C(37)-C(3) | 0.0695 | |||

| C(6)-C(30) | 0.0341 | |||

| C(31)-C(7) | 0.0983 | |||

| Gaussview orbitals | Crystal structure[6] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

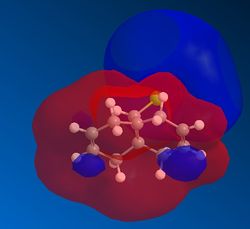

A population analysis was carried out on GaussView 5.0.9 using the DFT method with a RB3LYP hybrid functional and a basis set of 6-31G. The .fchk file for this can be found here

The molecular orbital above shows the HOMO-1 molecular orbital in orange/purple overlapping with the LUMO+1 which appears as red/blue. It can be seen that there is a noticeable overlap between the C-Cl σ* orbital with the π orbital of the alkene. The presence of this interaction results in reduced electron density in this alkene, rendering it less reactive than the alkene on the other side of the molecule. The overlap of the C-Cl σ* with the C=C π also results in a slight bending upwards of the alkene towards the C-Cl bond in order to maximise the overlap of this interaction. This acts to reduce the reduce of the molecule, resulting in a display of marked selectivity. This observation can also be seen in the crystal structure[6] shown above, indicating the power of modern computational chemistry.

Vibration |

In the molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) shown above, red indicates regions of positive charge, blue negative. THis further emphasises the reduced electron density on one of the alkenes due to the interaction with the C-Cl σ* orbital and the alkene π orbital. The jmol above helps visualise the vibration which accounts for this upwards movement of the alkene π orbital towards the C-Cl σ* orbital, increasing the overlap of this interaction. The .log file for the frequency analysis can be found here

To illustrate this point further, a comparison between the C-Cl bond lengths and the total energy in the original molecule and the monohydrated product is made using the DFT method with B3LYP hybrid functional and a 6-31G basis set. The table below summarises the results.

| Category | Compound 12 | Monohydrated product |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl bond length (Å) | 1.78900 | 1.78975 |

| Energy (kcal/mol) | 17.8945 | 24.7834 |

The longer C-Cl bond length in the monohydrated product compared to molecule 12 indicates a lack of the favourable alkene π with C-Cl σ* interactions, helping to explain the selectivity of this molecule during the [1+2] cycloaddition. More importantly, however, this interaction, when present, acts to stabilise the molecule as a whole, giving rise to a lower energy conformation in compound 12 compared to the monohydrated product. (17.8945 kcal/mol vs. 24.7834 kcal/mol)

Monosaccharide chemistry and the mechanism of glycosidation

The geometry of the oxenium cations A and B were optimised starting from four possibilities of each: two for the configurational possibilities of the acetyl group, each with two conformational orientations in which the carbonyl oxygen of the acetyl group is oriented on the top face or the bottom face of the oxenium carbon. This reaction acts as a great demonstratation of the neighbouring group effect. Initially, the structures were optimised using the MM2 force field on ChemBio3D, followed by further optimisation using the MOPAC/PM6 semi-empirical method.

| Molecule | MM2 | MOPAC/PM6 | C=O+ bond length(Å) | C-O(ester) bond length(Å) | C-O+=C bond angle(°) | Charge-dipole contribution in MM2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Up, up

|

49.7682 | -64.24951 | 1.268 | 1.418 | 122.0 | 1.0081 | |||

Up, down

|

41.6557 | -72.84289 | 1.274 | 1.426 | 121.3 | 0.4327 | |||

Down, down

|

27.9482 | -90.67267 | 1.344 | 1.491 | 120.4 | -16.1394 | |||

Down, up

|

40.2351 | -77.89957 | 1.277 | 1.431 | 119.3 | 1.0952 |

| Molecule | MM2 | MOPAC/PM6 | C=O+ bond length(Å) | C-O+=C bond angle(°) | Charge-dipole contribution in MM2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Up, up

|

43.6405 | -66.93992 | 1.306 | 106.3 | 1.4964 | |||

Up, down

|

39.4096 | -66.94392 | 1.306 | 106.3 | -2.9897 | |||

Down, down

|

103.7432 | -66.86683 | 1.324 | 106.8 | 2.7510 | |||

Down, up

|

44.2893 | -66.87764 | 1.324 | 106.8 | -0.3564 |

Both MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 produce very different values, albeit they tend to show the same trend. The MM2 force field cannot interpret the oxenium cations since they are non-classical. In contrast, the semi-empirical MOPAC/PM6 method goes some way to improving these calculations since it is able to take account of the neighbouring group effect. A striking difference to illustrate this point can be found on analysing the relative energy contributions for each molecule. Most noticeably, the charge-dipole contribution varies drastically using MM2. This is due to the limitations of the MM2 method in recognising the oxenium cations.

We cannot compare relative magnitudes between different methods, however, we can comment on the relative magnitudes of those calculated using the same method. The most stable isomer for cation A is the one with the most negative energy, which is the third isomer in the table above, where the acetyl group faces down and the carbonyl group is also oriented downwards. The energy associated with this is 27.9482 kcal/mol using the MM2 force field, while it is -90.67267 kcal/mol for the PM6 method. Both methods of calculating the energy agree that this is the isomer with the most negative energy. We can see that the the isomer where the acetyl group faces downwards results in a more stable molecule in each case, with energies of -90.67267 and -77.89957 kcal/mol, compared to when the acetyl group faces upwards, giving energies of -64.24951 and -72.84289 kcal/mol. This is likely due to steric effects since when comparing the jmols of each structure it appear the downwards configuration minimises the lone pair repulsions/interactions.

For the oxenium cation B, it is clear the length of the C=O bond is directly influenced by the orientation of the acetyl group from cation A. In each case, when the acetyl group in A is oriented upwards, the C=O bond length is found to be 1.306Å, compared to 1.324Å when oriented downwards. Likewise, the C-O+=C bond angle is consistent with this observation, since it is 106.3° for when the acetyl group is oriented upwards and 106.8° when downwards. A possible explanation for this is that when an oxygen lone pair attacks to form intermediate B, attack on the top face is slightly more favourable than the bottom

Week 2 - Mini Project - Simulation of spectroscopic data for a literature molecule

This part of the module looks at employing modern computational chemistry techniques to simulate the 1H and 13C NMR of a Taxol precursor provided. The experimental NMR data provided will then be compared to that which has been computed using GaussView 5.0.9

The literature paper for compound 18 can be found at the following DOI: DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

Compound 18

18 |

Optimisation using MM2

------------MM2 Minimization------------ Warning: Some parameters are guessed (Quality = 1). Iteration 283: Minimization terminated normally because the gradient norm is less than the minimum gradient norm Stretch: 5.2271 Bend: 18.8999 Stretch-Bend: 0.7601 Torsion: 22.5528 Non-1,4 VDW: 0.2582 1,4 VDW: 16.9806 Dipole/Dipole: -2.9011 Total Energy: 61.7776 kcal/mol Calculation ended -------------------------------------------

As shown above the calculated minimised energy using MM2 for compound 18 is 61.7776 kcal/mol.

Optimisation using the DFT method

Next, compound 18 was further optimised using the DFT method with a B3LYP hybrid function and the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. Confirmation of the optimisation is shown below.

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000021 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000004 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001459 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000192 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-3.036029D-08

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The energy for this optimised geometry was calculated to be -1651.80581870 a.u. which is equivalent to -1036524.67 kcal/mol. Of course, comparisons between the relative energies given from the MM2 force field and the DFT method cannot be compared.

NMR spectra analysis

The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were calculated using Gaussian, using the CPCM solvent model, with benzene as the solvent. This allows for comparisons to be drawn between these values and those found in the literature.[7] All spectra presented are referenced with respect to TMS in benzene using the mpw1pw91 method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set and the GIAO approach. The link to the Dspace can be found at the following DOI: DOI:10042/23097

1H NMR

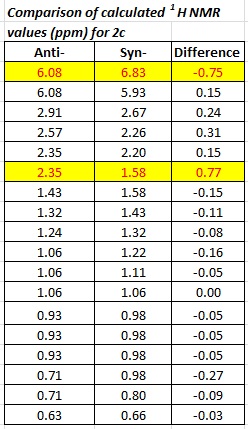

The 1H NMR was compared initially and the spectra can be found here. The table below summarises the findings.

The proton NMR data shows good agreement between the experimental data in the literature and the calculated data produced, falling within ±0.75 ppm. The greatest discrepancies were found as the chemical shift moved downfield, perhaps towards more delocalised environments, where it becomes more difficult to predict deshielding effects. Hence, this is likely to be the proton which is attached to C=C.

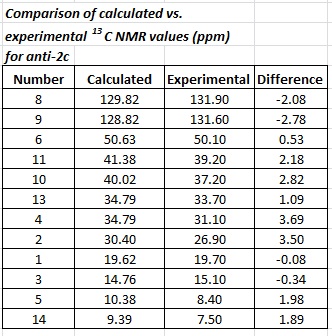

13C NMR

Next, the calculated 13C NMR was compared to that found in the literature and the differences between the two were computed. The spectra can be found here and the results are summarised in the table below.

From comparing the values, it can be seen that they all fall within ±5 ppm, except for one anomaly which differs by +13.15 ppm (highlighted in red above). This is a result of spin-orbit coupling errors due to a carbon being attached to a "heavy" element.[8] In this case, this is the carbon attached to the two heavier sulfur atoms.

Analysis of a chosen molecule

Introduction

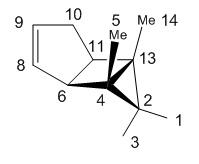

This section required researching a previously unseen molecule from the literature which has been synthesised and is known to have at least two isomers. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were calculated using GaussView, using the CPCM solvent model, with toluene as the solvent. This allows for comparisons to be drawn between these values and those found in the literature. All spectra spectra are referenced with respect to TMS in benzene using the mpw1pw91 method and 6-31G(d,p) basis set, using a GIAO approach. Comparisons were then made between the calculated values and the experimental ones in the literature.

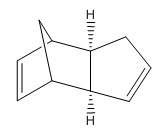

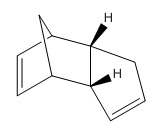

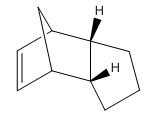

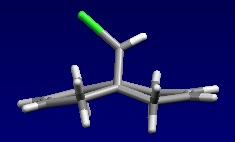

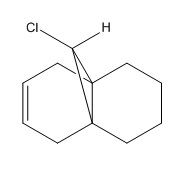

The molecule chosen by searching The Journal of Organic Chemistry online and was selected from the following paper. DOI:10.1021/ja026321n A number of housanes were synthesised from photodenitrogenation of the more complex cyclopentene-annelated DBH-type azoalkane 1c. The chosen housanes to investigate computationally were the retained housane, anti-2c, and the inverted housane, syn-2c (stereoisomers).[9]

| Anti-2c Jmol | Syn-2c Jmol | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Conformation of the optimisation of both structures can be seen below.

Syn-

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000011 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000003 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000784 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000172 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-9.797141D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Anti-

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000008 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000002 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.000726 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.000126 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-3.900704D-09

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

Comparison of relative energies of anti- and syn- 2c

| Parameter | Syn- | Anti- |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.7986 | 1.8006 |

| Bend | 50.1350 | 21.0153 |

| Stretch-Bend | -1.8401 | -1.2127 |

| Torsion | 19.3124 | 21.9108 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -0.3969 | -0.5415 |

| 1,4 VDW | 6.4297 | 2.1639 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3604 | 0.3565 |

| MM2 Total energy | 76.7991 | 45.4930 |

| MMFF94 Final energy | 99.8014 | 58.0175 |

| MOPAC/PM6 Heat of formation | 65.52445 | 22.92534 |

The data above indicates the major product should be the anti- isomer which is consistent across all methods used to calculate the energy, as well as concuring with the literature.[9] At 40°C, the ratio of anti:syn product has been found to be 80:20.[9] This is an unusual stereochemical preference, however, on closer inspection of the relative individual energies it can be seen that the bend energy is a significant contributor to the differences. This is because in the syn- conformation, the bending angle (related to Hooke's Law) is displaced further from equilibrium, resulting in a larger bend energy.[10] Several mechanisms have also been proposed to help explain this selectivity. One mechanism in particular has significant evidence, which suggests that the thermal denitrogenation of DBH proceeds directly to a nonstatistical 1,3-cyclopentadienyl diradical intermediate by concerted cleavage of both CN bonds. The preference for inversion is then rationalised due to the proposed momentum conservation.[11]

1H

The 1H NMR for the syn iosmer can be found here [ DOI:10042/23208 ] and the anti isomer here.[ DOI:10042/23207 ]

|

|

|---|

In general, for the syn- isomer, the values fall within ±0.35 ppm, indicating a good correlation between the data sets. There exits an anomaly for the most deshielded proton, which differs by +1.10 ppm. This is likely to correspond to the proton attached to carbon atoms 8 or 9 (labelled in upcoming images) since these form the C=C double bond. The presence of delocalisation in the alkene π orbital results in deshielding of the nucleus of the corresponding proton. The exact magnitude of these effects are difficult to predict, hence the discrepancy in the two differing values. This also highlights a limitation of this computational technique.

For the anti- isomer, the data sets again show good correlation, in general faling within ±0.33 ppm. In this case, this clearly illustrates a major advantage of modern computational chemistry in being able to obtain good fits for the data.

13C

The 13C NMR for the syn isomer can be found here [ DOI:10042/23208 ] and the anti isomer here.[ DOI:10042/23207 ]

|

|

|---|

The syn- isomer shows a reasonable fit between the calculated values and the literature values, although there are several falling outside of a ±5.00 ppm threshold. There major anomaly worth highlighting is that in yellow, which refers to carbon number 11. This exhibits a difference of +8.09 ppm. It is difficult to interpret this finding, but a possible explanation stems from a proposed interaction of the alkene with the bridging groups, which alters the nature of the electron density of the carbon atom in question. This is a very handwavy argument and one that will not be dwelled upon further, only to say that through the success of modern computational chemistry, this further highlights its limitations at times.

The anti- isomer shows a much better correlation, with all values falling within ±3.69 ppm.

Comparison of calculated NMR data for syn- and anti- isomers

1H

The values highlighted in the table above show where the two isomers differ most in their proton NMR spectra. This is a good starting point in differentiating the two isomers via spectroscopic methods. One of the protons displaying this marked difference in chemical shift between the two isomers is that of the alkene. The syn-isomer is deshielded by 0.75 ppm relative to the anti- isomer. The reason for this has to be attributed to the interaction of the bridging groups with the alkene due to their close proximty in the syn- isomer, resulting in a greater deshielding effect on the proton.

|

|

|---|

The molecular orbitals above are that of the HOMO-1 for both the anti- and syn- product. The alkene π bond is significantly larger for the syn- isomer which helps explain the greater deshielding seen for the one of the alkene protons since a larger electron cloud results in greater delocalisation, hence a greater deshielding effect.

The .fchk file for the population analysis of the anti- isomer can be found here and the syn- isomer here.

13C

As with the proton NMR table, the values in yellow above highlight the key differences found in the 13C NMR of the two isomers. The major differences are seen for carbon atoms 8, 5 and 11. For all but one carbon atom in both molecules, the syn- isomer is more deshielded than the anti- isomer. This draws on the same point mentioned earlier regarding the size of the π MOs for each isomer. The same argument can be used here.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of molecular mechanics has been used to determine the selectivity of an addition to a diene, as well as the preferred geometry of the cyclopentadiene dimer under kinetic or thermodynamic control. In addition, the techniques learnt have been used to successfully distinguish between two isomers from a reaction found in the literature. In terms of distinguishing between the isomers, both 1H and 13C NMR provided useful distinctions between the two, however, the more insightful was the 13C spectra. It has been confirmed using molecular mechanics that the anti- isomer for compound 2c is more stable than its corresponding syn- isomer, which is in agreement with the literature. An attempt has also been made to rationalise this stability by considering the mechanism through which the reaction proceeds.

References

- ↑ W.C.Herndon, C.R.Grayson, J.M.Manion; "Retro-Diels-Alder reactions. III. Kinetics of the thermal decompositions of exo- and endo-dicyclopentadiene" J. Org. Chem.; 1967, 32 (3); 526-529. DOI:10.1021/jo01278a003

- ↑ P.Caramella, P.Quadrelli, L.Toma; "An Unexpected Bispericyclic Transition Structure Leading to 4+2 and 2+2 Cycloadducts in the Endo Dimerization of Cylcopentadiene" J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2002, 124 (7); 1130-1131. DOI:10.1021/ja016622h

- ↑ Wiseman, J.R.; Pletcher, W.A. Bredtâs; "Rule III The Synthesis and Chemistry of Bicyclo[3.3.1]non-1-ene" J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1970, 956-962. DOI:10.1021/ja00707a035

- ↑ Koebrich, G.; "Bredt Compounds and the Bredt Rule."; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., 1973, 12, 464-473. DOI:10.1021/anie.197304641

- ↑ Fawcett, F.S. Chem. Rev.; 1950, 47, 219, DOI:10.1021/cr60147a003

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 B.Halton, R.Boese, H.S.Rzepa;J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2; 1992, 447-448, DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ L. Paquette, N.A. Pegg, D.Toops, G.D.Maynard, R.D.Rogers;J. Am. Chem. Soc.,; 1990, 112 277-283, DOI:10.1021/ja00157a043

- ↑ S.P.McGlynn, M.J.Reynolds, G.W.Daigre, N.D.Christodoyleas; J. Phys. Chem.; 1962, 66 (12); 2499-2505. DOI:10.1021/j100818a042

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 W.Adam et al;J. Am. Chem. Soc.,; 2002, 124, (41), 12192-12199, DOI:10.1021/ja026321n

- ↑ A.K.Rappe, C.J.Casewit, K.S.Colwell, W.A. Goddard; J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1992, 114 (25); 10024-10035. DOI:10.1021/ja00051a040

- ↑ M.B.Reyes, B.K.Carpenter; J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2000, 122 (41); 10163-10176. DOI:10.1021/ja0016809