Rep:Mod:64zoolane

Module 2

Introduction

Quantum mechanical methods of computational analysis can be applied to inorganic systems to carry out electronic structure calculations. The results allow analysis of bonding and structure, which may be used to support practical experiments in the laboratory. In module 2, Gaussian 09W was used to carry out computational analysis on small molecules and metal complexes. The set of programmes implement many different methods for carrying out total energy calculations, including molecular mechanics methods using forcefields, but mainly semi-empirical and ab initio molecular orbital-based methods.

For optimization, density functional calculations are employed to solve Schrodinger's equation for the electronic wavefunctions, using the Born-Oppenheimer approximation (where the large relative size of nuclei renders them immobile compared to electrons)for a set of nuclear co-ordinates (R). The nuclear co-ordinates are then progressively altered (R'), producing a new energy for each iteration E(R'), and thus the change of energy with respect to the nuclear coordinates (the RMS gradient) is calculated as the structure moves towards the lowest energy form. When the RMS gradient is at zero, the potential energy surface has zero gradient, as there are no forces to change the nuclear coordinates when the nuclei and electrons are at equilibrium. The second derivative of the potential energy surface can be calculated to determine if the point reached is a transition state (a maximum when the second derivative is negative), or the ground state (a minimum when the second derivative is positive). Gaussview 5.09 was used as the graphical interface to display the results of geometry optimization, frequency, molecular orbital and natural bond orbital calculations.[1]

The accuracy of the calculations is dependent on the chosen method and basis set. In module 2, for small molecules, the DFT B3LYP method was used with basis set 3-21G, as fewer errors would be incurred for simpler systems, reducing computational demand. For more complicated systems where errors incurred would be more significant, a loose optimization using the basis set LanL2MD was carried out, before using psuedo potentials with the basis set LanL2DZ to increase accuracy of calculations.

Optimization of BH3

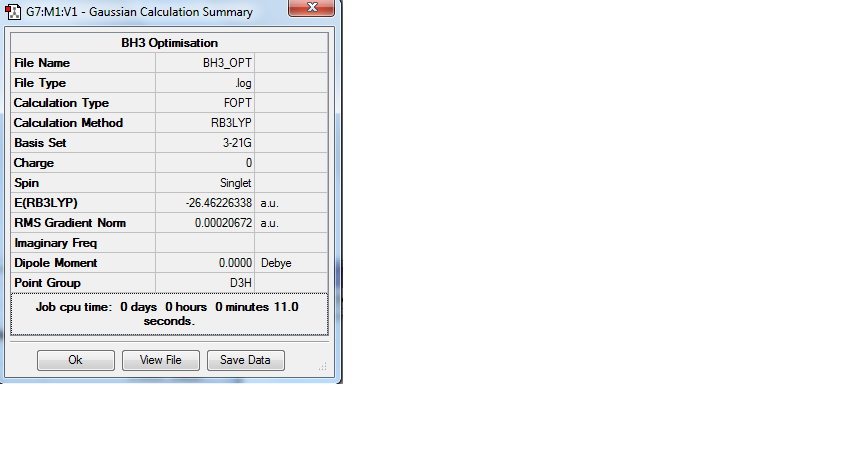

The bond lengths of a trigonal planar BH3 molecule were adjusted to 1.5Å, and the geometry optimized using the B3LYP method and the basis set 3-21G. The optimized structure had bond angles of 120 degrees, and bond lengths of 1.19 Å, which is concordant with literature values[2]. A summary of the optimization results is given by figure 1. The log file can be accessed at DOI:10042/to-9694

Figure 1: Summary of BH3 optimization

Figure 2: Graphs to show convergence of total energy and the RMS gradient during optimization

The summary shows that the RMS gradient is 0.00020672 au, very close to zero, which indicates that the optimization has been completed. The graphs displayed in figure 2 are the Total Energy curve and the RMS (root mean square) gradient. The total energy curve shows the energy of the molecule at each step of the optimization, essentially the program is travelling along the potential energy surface of BH3 until the minimum energy structure is found. The RMS gradient shows the gradient of the energy of the molecule at each step of the optimization, displaying how the gradient goes to zero as the minimum is approached. The graphs reflect how the parameters have converged during optimization in four steps.[3] Physically, the graphs reflect a gradual contraction in the bond lengths.

Molecular orbitals of BH3

The shapes and energies of the molecular orbitals of BH3 were calculated using the previously optimized structure, and the computated MOs placed on an MO diagram to compare quantitative and qualitative MO analysis. The MO diagram displayed by figure 3 is based on the linear combination of boron and the H3 fragment orbitals (determined with use of the reduction and projection formulae to form a representation table). The trigonal planar BH3 molecule belongs to the D3h point group, and so the symmetry labels of the orbitals can be determined using the D3h character table.

Using LCAO to construct a molecular orbital diagram means that qualitative analysis is required to determine the energy positioning of the orbitals. The relative energy of the two fragment orbitals were estimated by taking into consideration the fact that both boron and hydrogen are electropositive elements , thus the s-orbitals will be at similar energy levels. However, there is a small stabilization of the all in phase bonding fragment orbital of the H3 , which is therefore slightly lower in energy than the 2s boron atomic orbital. The boron 1s orbital is considered to be too low in energy to participate in bonding interactions with the H3 fragment orbital. The 1a2 molecular orbital is non-bonding, as there are no H3 orbitals of the same symmetry to combine with the B pz. orbital. The relative ordering of the 3a1' and 2e' was determined by considering that although s-s interactions are stronger than s-p interactions (which would lead to 3a1' being higher), the a1' FO energy levels are lower than the e' FO energy levels, and so the resulting 2e' MO is higher in energy than 3a1'. Boron contributes 3 valence electrons, and H3 contributes 3 electrons, thus 3 electron pairs are used to fill up the MOs from the lowest energy.[4]

The MO diagram shows that the LUMO of BH3 is a low energy non bonding pz orbital, which indicates that BH3 will be susceptible to accepting electrons from HOMOs of higher energies. Furthermore, accepting electrons into the non-bonding LUMO of BH3 will not affect the overall bonding of the molecule, therefore BH3 is a lewis acid that will accept electrons from a base.

Figure 3: Molecular orbital diagram of BH3

Table 1 shows that the computational results are concordant with the LCAO representation of the MOs, as for all the computationally determined MOS the positive and negative regions of electron density can be matched with in phase or out of phase overlap of the LCAO MOs. For both methods, the HOMO was identified as one of the two degenerate e' bonding orbitals, and the LUMO identified as the non-bonding pz orbital. The relative energy of the 1s boron atomic orbital was calculated to be -6.73023 kj/mol, which confirms that it is too low-lying to contribute to bonding.

One difference in the two approaches to constructing MOs is that the LCAO method does not accurately predict the magnitude of contribution of each atomic orbital (further calculation is required to predict the relative coefficients). This can be observed in table 1, where the non-bonding 2a2' is more diffuse in appearance for the computed MO, than the LCAO representation. For the LCAO method, it is difficult to determine the relative energies and extent of orbital splitting, as for the LCAO approach it was predicted that the anti bonding 2e' MOs would lie higher in energy than the antibonding 3a1'. However, the computational results show that the antibonding 3a1' is actually higher in energy (0.19236 kj/mol) than the antibonding 2e' MOs (0.19236 kj/mol). Whilst this demonstrates that computational methods are more accurate for MO analysis than the LCAO method, the LCAO method does correctly identify the energy ordering of the HOMO and LUMO, which is important for explaining the reactivity of BH3, and so the limitations of the LCAO prediction are not so significant.

The output of the MO analysis can be found at DOI:10042/to-9727

Natural bond orbital analysis of BH3

Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis is used in computational chemistry to determine the electron density in atoms, and in the bonds between atoms. NBOs are considered to be intermediate between AOs and MOs, and so the NBO analysis takes the delocalised electron picture of MO analysis, and converts it back to the 2e-2c bonding picture. [5]The charge distribution of BH3 is shown in figure 4. It is apparent that the boron atom is highly electron deficient, as the log file of the population analysis shows that the natural charge of boron is 0.33, whilst the hydrogen atoms have an equal charge distribution of -0.11 each. This charge distribution confirms that BH3 is a strong lewis acid, as the boron atom is expected to have an unoccupied, low energy pz orbital.

|

Figure 5: Summary of Natural Population Analysis on BH3

Summary of Natural Population Analysis:

Natural Population

Natural -----------------------------------------------

Atom No Charge Core Valence Rydberg Total

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

B 1 0.33161 1.99903 2.66935 0.00000 4.66839

H 2 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 3 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

H 4 -0.11054 0.00000 1.11021 0.00032 1.11054

=======================================================================

Furthermore, the NBO analysis divides the electron density of the BH3 into atomic like orbitals, which are then used to form 2e-2c bonds. The log file details the contribution of each atom to the bonds, and the s and p contributions too (figure 6). The results show that the first three bonds (BD) are between boron and hydrogen, where 44.48% of the bond is contributed from the boron orbitals which have a hybridisation of 33%s+66%p, while 55.52% of the bond comes from the hydrogen orbital which is 100%s. Therefore the boron has formed 3 sp2 hybrid orbitals that interact with the s atomic orbitals of one hydrogen atom. The NBO analysis identifies the core 1S orbital on boron (CR), as it has 100% s character, corresponding with the 1S B orbital predicted in the MO analysis to be so low in energy that it did not combine with the hydrogen fragment orbital. The energy ordering of the occupied orbitals is therefore different for the NBO analysis compared with the MO analysis. The lone pair orbital in the NBO analysis (LP) should correspond to the empty LUMO from the non-bonding pz orbital that was predicted in the LCAO analysis. However, the NBO analysis describes the lone pair orbital as being 100%s, which shows a discrepancy between the methods. Similarly, the 6th, 7th and 8th NBOs have orbital contributions which disagree with that predicted by MO analysis, which suggests that NBO characterization breaks down for the unoccupied orbitals. [6]

Figure 6: Natural Population Analysis on BH3 - Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99853) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.48%) 0.6669* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.52%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99903) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

6. (0.00000) RY*( 1) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

7. (0.00000) RY*( 2) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

8. (0.00000) RY*( 3) B 1 s( 0.00%)p 1.00(100.00%)

The 'Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis' section does not contain any values of interest (over 20 kcal/mol), which confirms that no MO mixing has occured. This section shows any interactions between bonding NBOs into non bonding or anti-bonding NBOs.[7]

Vibrational analysis of BH3

Frequency analysis was applied to the optimized BH3 molecule and the output of the frequency analysis can be found at DOI:10042/to-9728 . Frequency analysis calculates the second derivative of the PES, to determine whether the optimized molecule was at a transition state or a ground state. Each vibrational mode has a PES, and the minimum occurs for the most stable structure, therefore the calculated frequencies should be positive for a ground state structure. Any negative values occur for a maximum turning point (transition state), thus these values must be discarded as the optimization has not been successful. Table 2 shows the vibrational modes of BH3, where all the frequencies are positive and confirmed by literature values[8], therefore confirming that the structure was at a ground state.

The same basis set and method (B3LYP/3-12G) was used for the optimization and vibrational analysis. The summary of results shows that the total energy after the frequency optimization was the same as that after the first optimization (-26.46 au), showing that the structure has not changed. The output file of the frequency analysis was opened and the low frequencies (figure 7) analyzed. The low frequencies refer to motions about the centre of mass of the molecule, and the better the calculation, the closer to zero these values will be. The highest low frequency is 0.2122, which implies that a more accurate method than B3LYP could be employed for the frequency analysis.

Figure 7: Low frequencies of BH3

Low frequencies --- -66.7746 -66.3724 -66.3720 -0.0021 0.0030 0.2122 Low frequencies --- 1144.1477 1203.6411 1203.6421

|

BH3 has 3N-6 vibrational degrees of freedom (N=4)therefore 6 vibrational frequencies have been calculated. However, only three peaks appear on the IR spectrum (figure 8). This is because there must be a change in the dipole moment for a mode to be IR active. Therefore symmetrical vibrational transitions (a1')will not appear on the spectrum, and has an absorption intensity of zero. The peak at 1144 cm-1 corresponds to the a2 vibrational mode, whilst the peaks at 1204 cm-1 and 2737 cm-1 each represent the pairs of degenerate e' vibrational modes.

TlBR3 calculations

Optimization of TlBr3 requires the use of a pseudo potential, as the molecule contains heavier atoms so better simulation is needed. Since BH3 contains first row elements, the effects caused by valence electrons would be minimal compared with TlBr3 , so the increased computation time to improve the approximation would not be advantageous. The calculation method B3LYP with LanL2DZ was used for the optimization. LanL2DZ uses a medium level basis set of D95V on first row atoms and Los Alamos ECP pseudo potentials on heavier elements.[9] The symmetry of the molecule was restricted to D3h, and the summary of results displayed in figure 9. The output file for the optimization can be found at DOI:10042/to-9729

Figure 9: Summary of results for optimization of TlBr3

Figure 9 shows that the optimized bond angle was 120 degrees, and the optimized bond length 2.65 Å, which are similar to literature values[10] (literature bond length 2.52 Å, bond angle 120 degrees). Figure 9 also shows that the RMS gradient is 0.0000009 au, which is close to zero and further confirms that the optimization was successful.

Frequency analysis was applied to the optimized structure, using the same method and basis set. This is important as using different methods will perform the calculation in a different way, and different basis sets will produce different accuracies, leading to non comparable results.

As discussed previously for the BH3 analysis, frequency analysis is required to ensure that the structure obtained is at a ground state; at a minima on the PES. The vibrational frequencies computed were all positive, confirming that the structure was in ground state. This is because the frequency analysis essentially calculates the second derivative of the PES, and so negative frequencies would result in maxima, suggesting that the structure is a transition state, therefore the optimization has not been successful.

The output can be found at DOI:10042/to-9730 . The computationally obtained frequencies (table 3) were compared with literature values[11], and found to be fairly close. The accuracy of the calculation was further confirmed by observing the low frequencies of the output file (figure 10).

Figure 10: Low frequencies of TlBr3

Low frequencies --- -3.4213 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9367 3.9367

The low frequencies are much lower than the vibration mode frequencies, and moreover they are close to zero, therefore confirming that the frequency calculation was of good accuracy. The lowest real normal mode is 46.4cm-1.

| Vibrational mode number | Form of vibration | Description of vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Literature value of frequencyJ. E. [12]/cm-1 | Intensity | D3h Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Scissor (in plane) : the two bromides move upwards and downwards symmetrically | 46.4 | 47 | 3.69 | e' |

| 2 |  |

Twist (in plane) One Br-Tl-Br angle is held constant, whilst another contracts and the third is increased. | 46.4 | 47 | 3.69 | e' |

| 3 |  |

Wag (out of plane bend): all the bromides move in and out in a concerted motion | 52.1 | 63 | 5.85 | a2 |

| 4 |  |

Symmetric stretch : The thallium atom is stationary, the three bromide atoms move in and out at the same time | 165 | 185 | 0.0000 | a1' (totally symmetric) |

| 5 |  |

Asymmetric stretch : One Tl-Br bond has constant length, whilst the remaining two bonds move in and out asymmetrically. | 211 | 203 | 25.5 | e' |

| 6 |  |

Asymmetric stretch: Two Tl-Br bonds move in an out symmetrically, whilst the third stretches asymmetrically (with respect to the other two bonds). | 211 | 203 | 25.5 | e' |

|

Similar to the BH3, the totally symmetrical vibrational mode a1' is not IR active as it does not create a dipole moment in the molecule, so does not appear on the spectrum and the absorption is zero. There are three peaks on the IR spectrum shown in figure 11. The peak at 46 corresponds the degenerate e' vibrational modes 1 and 2. The peak at 52cm-1 corresponds to the a2 vibrational mode 3, and the peak at 211cm-1 corresponds to the degenerate e' vibrational modes 5 and 6. Comparing the TlBr3 with the BH3, the lower wavenumber of the vibrations for the TlBr3 suggests that the bonds are weaker than in BH3, which is expected as the atoms of TlBr3 are heavier, leading to lower frequency vibrations.

What is a bond?

A bond occurs when a region of electron density is electrostatically attracted to two positive nuclei simultaneously, leading to the formation of compounds and molecules. The stronger the electrostatic attraction between the nuclei and the region of density, the stronger the bond, and the closer the nuclei are held together. In some structures in Gaussview, the programme does not draw in the expected bonds. This is because bonds are based on distance criteria in Gaussview, and so if the bond exceeds this predefined value then the programme does not show the bond. Therefore it should be remembered that if no bond is shown in Gaussview, there may still be significant bonding interaction between two atoms.[13]

cis and trans isomerism of [Mo(PCl3)2(CO)4]

In the second year inorganic synthesis lab, cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 were prepared. The cis isomer was expected to produce 4 CO absorption bands, whilst the trans isomer was only expected to produce one absorption band. This is because the trans isomer belongs to a higher symmetry point group (D4h), compared with the cis isomer (C2v), and so there are fewer IR active modes. Therefore the computational techniques used previously are suitable for identifying different stereoisomers. Vibrational analysis is especially useful, as the carbonyl oscillations usually occur in the range of 2100-1750 cm-1, and this region is usually free from interference of absorption bands from other functional groups.[14]

For this computational exercise, the phenyl rings of the PPh3 groups have been replaced by chlorine atoms, as these have a similar electronic contribution to the bonding as the phenyl rings, and are large sterically, but are much less computationally demanding as they contain fewer electrons.

The two isomers were optimized firstly using loose criteria with the B3LYP method, and the low level minimal basis LanL2MB pseudo-potential. This is because if normal convergence criteria were used, the limits set would be more accurate than the method use, and so the calculation may not converge as the limit will never be reached. The resulting loosely optimized structure does not have accurate dihedral angles, as the minimum reached may not be the lowest energy one. The output files for this first optimization can be found here for the cis isomer: DOI:10042/to-9751 and for the trans isomer: DOI:10042/to-9752 .

Figure 12: Cis and trans isomers after loose optimizations |

|

|

To obtain the lowest energy minima, the loosely optimized molecules (figure 12) were manually adjusted so that for the cis isomer, one Cl points upwards parallel to the axial bond, whilst another Cl of another group points down, to ensure the torsion angle of the PCl3 groups is 180 degrees. For the trans isomer, the loosely optimized structure was manually adjusted so that both PCl3 groups were eclipsed, to make the torsional angle 0 degrees.

A final optimization was then carried out, using the B3YLP method and the LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and basis sets using the normal optimisation criteria. LANL2-DZ has DZ (instead of MB as in LANL2-MB) which stands for double zeta. It is a much better basis set and pseudo-potential than the minimal basis option. With the much better pseudo-potential and basis set, tighter convergence was required, and so the electronic convergence was also increased by adding "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" into the additional keywords when setting up the calculation.

The output file for the final optimization of the cis isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9765 and for the trans isomer at DOI:10042/to-9766 . However, for a metal complex, it is important to consider the d-orbital interactions. The LanL2DZ pseudo potential and basis set applied only has minimal basis, the valence s and p orbital functions, so the dAO functions are not included in the output. Since phosphorus is hypervalent and contains low lying dAOs, the log files from the final optimization output were adjusted accordingly, and the isomers were optimized again with the dAO contributions taken into account. The adulterated output file for the cis isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9847 and the trans isomer output at DOI:10042/to-9848 . The structures of the final optimized structures are shown in figure 14

Figure 14: Cis and trans isomers after final optimization |

|

|

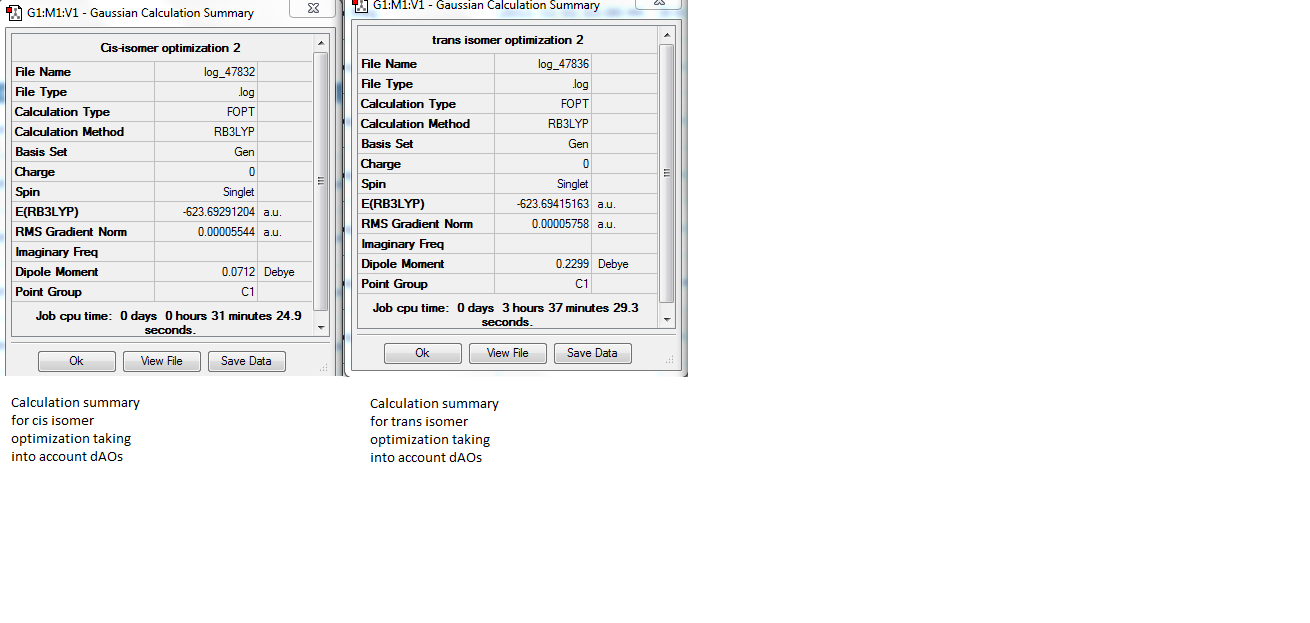

Figure 15: Calculation summaries of the final optimized cis and trans structures

The calculation summaries show that for both the isomers, the RMS gradient was close to zero, suggesting that the optimization was successful. The relative energies of the isomers (converted from hartrees to kj/mol) were -1637505.741 kj/mol for the cis isomer, and -1637508.995 kj/mol for the trans isomer. The trans isomer is therefore 3.25 kj/mol more stable than the cis isomer, which is concordant with literature observations[15]. Since the accuracy of relative energies is reported as being +/- 10kj/mol, the difference in energies between the two isomers is not of great accuracy. This suggests that the two isomers could interconvert at room temperature.

One reason for the trans isomer being relatively more stable is that the two PCl3 groups are further apart that for the cis isomer, reducing steric clashes. Changing the relative stability of the cis and trans isomers can therefore be done by altering the size of two 'L' ligands. Another method of changing the relative energies of the isomers is to swap the PCl3 with an electron rich group. This would donate some electron density on the metal centre of the complex, increasing the backbonding to C=O. The increased backbonding would the bond to weaken, making the orbitals are more diffuse, and so the cis isomer is favoured. Another way of changing the relative energy of the isomers is to introduce hydroxyl groups to the ligands. The strong hydrogen bonding that can take place between the hydroxyls can hole the molecule together, stabilizing it.

Table 5: Comparison of bond angles and bond lengths

| Bond | Calculated cis bond length (Å) | Literature cis bond length (Å)[16] | Calculated trans bond length (Å) | Literature trans bond length (Å)[17] |

| Mo-C | 2.02 | 2.02 | 2.06 | 2.01 |

| Mo-P | 2.48 | 2.57 | 2.42 | 2.50 |

| C-O | 1.18 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| Bond Angle | Calculated cis bond length (o) | Literature cis bond angle (o[18] | Calculated trans bond angle (o) | Literature trans bond angle (o)[19] |

| P-Mo-P | 94.3 | 104.6 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| C-Mo-C | 87, 179 | 89, 179 | 89, 179 | 83 |

The bond angles and bond lengths of the computationally determined isomers were compared to literature values, to confirm the reliability of the optimizations. As shown in table 5, most of the calculated values were close in value to the literature values. However, one significant discrepancy is the difference in length of the Mo-P bond in both the isomers. This may be due to the trans effect that exists in the cis-isomer. The trans effect is caused by donation of electron density from the lone pair on a phosphorus ligand situated trans to a carbonyl group, into the pi-acceptor of the CO, and so the Mo-C bond distances decrease in comparison to a ligand without a phosphorus group situated trans to it. There is also a discrepancy between the calculated and literature values of the P-Mo-P bonding angle for the cis isomer, which may be caused by the substitution of the phenyl groups with chlorine atoms, for this module.

Frequency analysis of the cis and trans isomers

Frequency analysis was carried out on the cis and trans isomers to determine whether the first derivatives found by the optimization were maxima or minima. The same method (B3LYP) and pseudo potential (LanL2DZ, with the additional basis set added to include the dAOs) was used. The output for the frequency analysis of the cis isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9863 and of the trans isomer at DOI:10042/to-9864 .

For the cis isomer, all frequencies calculated were positive, confirming that the optimized structures were at minima, and so were at ground state. For the trans isomer, whilst most of the frequencies calculated were positive, the first frequency was negative, and the second very low. The first two low frequencies for each isomer were animated.

Table 6: Low frequencies of the cis/trans isomers

| Cis isomer | Trans isomer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode number | Form of vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Mode no. | Form of vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | |

| 1 |  |

11 | 0.0163 | 1 |  |

-0.76 | 0.06 | |

| 2 |  |

20 | 0.0042 | 2 |  |

5.6 | 0.0 |

For low frequencies to occur, the temperature must be low. These low vibrational modes will be empty, as at room temperature the molecule will vibrate with enough energy to fill higher vibrational modes. Since higher energy levels are populated in this way, the molecule will not be in a ground state, which may explain why the value for the first mode of vibration for the trans isomer is negative. The low frequencies may also reflect the conversion of the cis and trans isomers with each other at room temperature.

Table 7: Carbonyl stretch analysis

| Cis isomer | Trans isomer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode no. | Frequency ((cm-1) | Literature Frequency(cm-1)[20] | Intensity | Frequency ((cm-1) | Literature Frequency(cm-1) [21] | Intensity | ||

| 42 | 1938 | 1897 | 1604 | 1940 | 1896 | 1607 | ||

| 43 | 1942 | 1908 | 813 | 1940 | 1896 | 1607 | ||

| 44 | 1952 | 1927 | 588 | - | - | - | ||

| 45 | 2019 | 2023 | 545 | - | - | - |

Both the IR spectrum of the trans isomer and table 7 show that there is one carbonyl stretch at 1940 cm-1, due to two vibrational modes that are degenerate in energy. The IR spectrum and table 7 also show that the cis isomer has four stretches in the carbonyl stretching region, which was expected due to the higher symmetry of the trans isomer. This higher symmetry causes some vibrational modes to be IR inactive, as some combined vibrations may be oppositely directed and equal in magnitude to each other. However, the lower symmetry cis isomer has each of the carbonyls situated in a unique environment with respect to the other carbonyls, therefore four unique modes are seen. Whilst the trend of the calculated values agrees with that of the literature values, there is a significant difference between the values, which may be caused by the substition of the phenyl groups with chlorine atoms for this computational exercise.

Mini project: Nitro-nitrito linkage isomerism in the penta-amminecobalt (III) complex

Introduction

The nitrite ligand is an ambidentate ligand, which can co-ordinate to a metal centre by the nitrogen atom or an oxygen atom. For the penta-amminecombalt (III) complex, the oxygen co-ordinated red complex [Co(NH3)5(ONO)]2+ is less stable than the yellow nitrogen co-ordinated complex [Co(NH3)5(NO2)]2+.

Figure 17[22]

The nitrito linkage isomer [Co(NH3)5(ONO)]2+ is the kinetic product which is formed first, but at room temperature it isomerizes to form the thermodynamic product, the nitro linkage isomer [Co(NH3)5(NO2)]2+. Using computational techniques such as MO, NBO and frequency analysis for this mini project, these observations can be rationalized, and the characteristic isomerism of the nitrite ligand explored.[23]

Optimization of the nitro and nitrito linkage isomers

The linkage isomers were firstly optimized using loose criteria, using the B3LYP method and the minimal basis LanL2MB pseudo-potential. The output of the nitro isomer optimization can be found at DOI:10042/to-9775 and the output for the nitrito isomer optimization can be found at DOI:10042/to-9776

The linkage isomers were then optimized using the B3LYP method, and the GEN basis set. This allowed the LanL2DZ to be placed on the cobalt atom only, whilst a normal 6-311G basis set was used for the remaining nitrogen, oxygen and hydrogen atoms, which helped to reduce computational demand. The output for this final optimization of the nitro isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9786 and the output for the final optimization of the nitrito isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9789 .

The pseudo potential was placed only on the cobalt atom, to reduce computational demand.

Figure 18: Nitro and nitrito linkage isomers after final optimization |

|

|

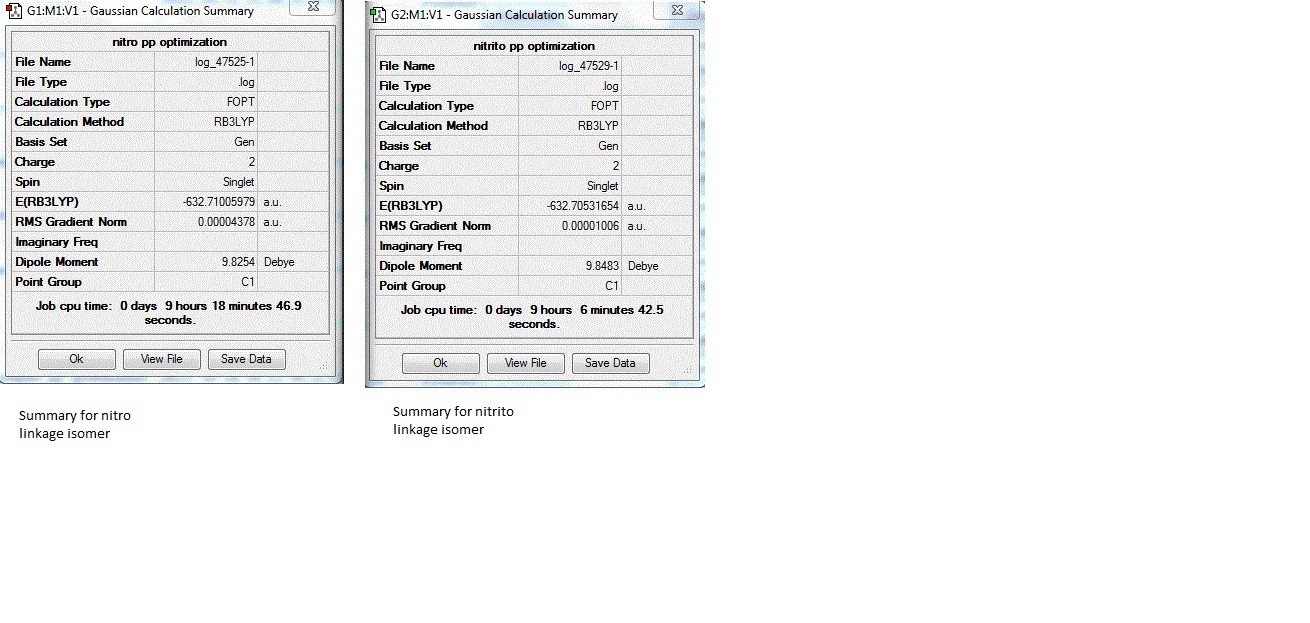

The calculation summaries for the final optimization of the linkage isomers are shown below:

The results summary show that for both isomers the RMS gradient is close to zero, suggesting that the optimization was successful. The relative energy of the isomers converted to kj/mol gives is -1661180.262 kj/mol for the nitro compex, and -1661167.809 kj/mol for the nitrito complex. The nitro complex is therefore 12.45342423 kj/mol more stable than the nitrito complex. Since the error for relative energies is +/-10 kj/mol, this suggests that the relative energy difference is large enough to be significant. These relative energies are concordant with the experimentally determined results of the nitro isomer being the more stable isomer.

However, for a metal complex, it is important to consider the d-orbital interactions. The LanL2DZ pseudo potential and basis set applied to the cobalt atom only has minimal basis, the valence s and p orbital functions, so the dAO functions should be considered too. The log files from the final optimization output were adjusted accordingly, and the isomers were optimized again with the dAO contributions taken into account. The adulterated output file for the nitro complex can be found at DOI:10042/to-9851 and the output for the nitrito isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9850 . Unfortunately this optimization was unsuccessful and so the previous optimized structures were used for the vibrational, MO and NBO analysis.

Vibrational analysis

Vibrational analysis is required to determine whether the turning points found from the optimization of the isomers are minima or maxima. The vibrational analysis was attempted using B3LYP/Gen (the same method and basis set as used for the optimization), but this was unsuccessful, and the output file for the nitro complex can be found at DOI:10042/to-9846 . The structure optimized under loose criteria was thus used for the vibrational analysis. The output for the vibrational analysis of the nitro complex was DOI:10042/to-9855 and the output for the nitrito complex was DOI:10042/to-9858 The absorptions affecting the nitro/nitrito ligand were analysed.

| Form of vibration | Description of vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Literature value of frequency/cm-1[24] | Assignation of vibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The nitrogen atom remains stationary, the oxygen atoms move in and out of the plane of the molecule in a wagging motion | 87.0 | 245 | NO2 (wag) |

|

Twist (in plane) One Br-Tl-Br angle is held constant, whilst another contracts and the third is increased. | 446 | 455 | Cobalt-Nitrogen stretch |

|

The nitrogen atom rocks as the oxygen atoms move in a 'wagging' motion | 744 | 620 | NO2 (wag) |

|

The nitrogen atom rocks back and forth, the oxygen atoms remain stationary | 1294 | 1315 | NO2 (rocking) |

|

The nitrogen and oxygen atoms move together in opposite reaction to produce a scissoring action | 1425 | 1470 | NO2 |

| Form of vibration | Description of vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Literature[25] value of frequency/cm-1 | Assignation of vibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rocking of the stationary ONO group from the oxygen attached to the cobalt | 313 | 340 | Cobalt-oxygen stretch |

|

Scissoring motion as the oxygen atoms move in and out together in the opposite direction to the nitrogen atom | 760 | 820 | ONO (scissor) |

|

Terminal oxygen remains stationary, the other oxygen and the nitrogen move in opposite directions to each other in a strong N-O stretch | 1060 | 1050 | N-O stretch |

|

The terminal oxygen moves in the opposite direction to the nitrogen atom, whilst the bridging hydrogen remains stationary | 1444 | 1400 | N=o stretch |

|

|

The vibrational analysis allows identification between the two linkage isomers, as when bonding can occur on either the N or the O, differences in absorption frequencies occur in the spectra. Five distinctive vibrational modes were allocated to the nitro isomer, whils four modes were allocated to the nitrito. Comparison to literature values was fairly good, although there were some discrepancies, such as for the first nitro complex vibrational mode. This was most likely due to the inaccurate basis set and method used for the calculation. The change in symmetry of the molecule from a C2v to Cs is a reason as to why different absorption bands are expected.

MO and NBO analysis of the nitro and nitrito linkage isomers

The shapes and energies of the molecular orbitals of the linkage isomers were computated, using the B3LYP method, and the LanL2MB, as unfortunately the NBO analysis was unsuccessful using the more accurate pseudo potential LanL2DZ. The output file for the NBO analysis of the nitro isomer can be found at DOI:10042/to-9923 and the nitrito isomer NBO analysis can be found at DOI:10042/to-9924 . The computationally determined MOs were considered alongside a LCAO molecular orbital diagram for an octahedral complex containing a strong field pi acceptor ligand (NO2-) and a weak field pi donor ligand (ONO-).

An MO diagram of a pseudo-octahedral complex (which really has C4v symmetry) containing one pi acceptor ligand is shown in figure 17, for comparison with the computationally determined MOs for the nitro isomer, as the NO2- ligand is considered to be a pi acceptor.

Figure 21[26]: MO diagram of metal complex containing a pi acceptor ligand

From figure 21, it can be seen that 11 MOs have been formed from the fragment orbitals, and the 7 highest energy orbitals were analysed from the computationally determined MOs. The nitro ligand is L-type 2 electron donor, so the nitro complex contains 19 electrons, whilst the nitrito ligand contains 18 electrons. The nitro L-ligand is essentially converting into an anionic X-ligand, and so the electronic structure of the complex will be perturbed, and so differences in electron distribution are expected for the molecular orbitals.

| MO number | MO symmetry label | LCAO representation of MO[27] | Computationally determined MO | Relative energy (kj/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | e |  |

|

-0.23019 |

| 47 | e |  |

|

-0.30537 |

| 46 | b1 |  |

|

-0.33803 |

| 45 (LUMO) | a1 |  |

|

-0.35296 |

| 44 (HOMO) | b2 |  |

|

-0.49337 |

| 43 | e |  |

|

-0.50729 |

| 42 | e |  |

|

-0.51083 |

(For the degenerate bonding and antibonding e orbitals, only one LCAO representation has been drawn). It can be seen from table 9 that the computationally determined MOs form a good match with the LCAO predictions, thereby helping to support the statement that the nitro ligand is a pi acceptor ligand. Discrepancies that occur include the energy ordering of the molecular orbitals, as the degenerate non bonding orbitals e (48 and 47) have significantly different relative energies. This could suggest that the LCAO model does not account for different degrees of field splitting caused by various pi acceptors accurately, and the pi acceptor abilities of the nitro ligand could distort the model predicted by LCAO. The shapes of the computational MOs correspond well with the LCAO predictions.

For an octahedral complex with a pi donor ligand such as the Nitrito ligand, the MO diagram of an octahedral complex with just sigma donors does not change very much, although a pi donor ligand will decrease the octahedral field splitting, as the t2g level will be raised. However the shape of the ONO- ligand distorts the symmetry of the complex to Cs.

It can be seen from table 10 that the greatest electron density is located on the bridging oxygen, so the negative charge of the nitrito ligand is not on the terminal oxygen. In contrast, table 9 shows that the electron density of the nitro ligand is mostly evenly distributed, which reflects the character of a neutral L-type ligand, as opposed to the anionic X-type ligand character of the nitrito ligand. It was noted that the relative energy of the LUMO for the two isomers showed that the HOMO for the nitro complex was lower in energy than for the nitrito complex, suggesting that the nitro complex is more stable.

NBO analysis was carried out for the isomers, (even though the dAO contributions were not taken into account, as the NBO analysis allows further exploration of the difference in contributions to the oxygen atoms in the nitrito ligand):

19. (1.96600) BD ( 1) O 22 - N 23

( 56.83%) 0.7539* O 22 s( 12.45%)p 7.04( 87.55%)

0.0000 -0.3528 0.7994 0.4861 -0.0100

( 43.17%) 0.6570* N 23 s( 9.74%)p 9.27( 90.26%)

0.0000 -0.3120 -0.9486 0.0517 -0.0078

20. (1.99615) BD ( 1) N 23 - O 24

( 39.75%) 0.6305* N 23 s( 0.02%)p99.99( 99.98%)

0.0000 0.0134 -0.0126 -0.0004 0.9998

( 60.25%) 0.7762* O 24 s( 0.02%)p99.99( 99.98%)

0.0000 0.0138 0.0051 0.0682 0.9976

21. (1.95893) BD ( 2) N 23 - O 24

( 47.79%) 0.6913* N 23 s( 13.91%)p 6.19( 86.09%)

0.0001 -0.3730 0.1723 0.9117 0.0076

( 52.21%) 0.7226* O 24 s( 10.30%)p 8.70( 89.70%)

0.0000 -0.3210 -0.2572 -0.9089 0.0679

The NBO analysis shows that the contribution of the nitrogen atom to the two different bonds is actually fairly similar (47.79% compared with 43.17%), which suggests a degree of delocalisation in the nitrito ligand:

Figure 22 [28]

Conclusion

It is necessary for the interaction of dAOs to be included in the analysis of the nitro and nitrito complexes, otherwise inaccurate conclusions may be formed, as the cobalt d orbitals interact with the ligand orbitals. From the analysis that was carried out, the nitro complex was determined to be the most stable, and some characteristics of the ambidentate ligand were explored using computational methods.

References

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/3b_understand_opt.html

- ↑ M S Schuurman et al., Journal of computational chemistry, 26, 11, 2005

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/3b_understand_opt.html

- ↑ P Hunt, 'Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry', Lecture 4, 2011, p3

- ↑ J T. Nelson, W J. Pietro Inorg. Chem., 1989, 28 (3), pp 544–548

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/5b_nbo_analysis.html

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/5b_nbo_analysis.html

- ↑ P. Meier, M. Neff, and G. Rauhut, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 7, 148 (2011)

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/4b_creating_bcl3.html

- ↑ J Blixt et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117 (18), pp 5089–5104

- ↑ J. E. D. Davies and D. A. Long J. Chem. Soc. A, 1968, 2050-2054

- ↑ D. Davies and D. A. Long J. Chem. Soc. A, 1968, 2050-2054

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/10b_MoC4L2_opt.html

- ↑ J D Woolins, Inorganic Experiments, 2010, p139

- ↑ 'Crystal structures of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] and 1,4-bis_diphenylphosphino)-2,5-difluorobenzene' - G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1977, 254, 167-171

- ↑ 'Steric Contributions to the Solid-State Structures of Bis(phosphine) Derivatives of Molybdeum Carbonyl. X-ray Structural Studies of cis-Mo(CO)4[PPh3-nMen]2 (n = 0, 1, 2)' - F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthhammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294-299

- ↑ 'Crystal structures of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] and 1,4-bis_diphenylphosphino)-2,5-difluorobenzene' - G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1977, 254, 167-171

- ↑ 'Steric Contributions to the Solid-State Structures of Bis(phosphine) Derivatives of Molybdeum Carbonyl. X-ray Structural Studies of cis-Mo(CO)4[PPh3-nMen]2 (n = 0, 1, 2)' - F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein and B. W. S. Kolthhammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 294-299

- ↑ 'Crystal structures of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] and 1,4-bis_diphenylphosphino)-2,5-difluorobenzene' - G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1977, 254, 167-171

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2681.

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, 1964, 3, 702-711

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~chemlab/chem6/cobalt4/full_text/chemistry.html

- ↑ I Grenthe, E Nordin Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18 (7), pp 1869–1874

- ↑ G Socrates, 'Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies', 3rd edition, 1994, p317

- ↑ G Socrates, 'Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies', 3rd edition, 1994, p317

- ↑ P Hunt, 'Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry', 2010, Lecture 8, p7

- ↑ P Hunt, 'Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry', 2010, Lecture 8, p7

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~chemlab/chem6/cobalt4/full_text/chemistry.html