Rep:Mod:3080ecm10mod3

Computational Laboratory 2012 - Transition States and Reactivity

Emily Monkcom

Introduction

Computational chemistry is taking on an ever-increaing importance within chemistry. Its ability to explore the realms of quantum nechanics and reaction coordinates make it a key component within research and industry. In this computational lab module, Gaussian 9.0 and GaussView 5.0.9 have been used to optimise and analyse transition states belonging to the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and the Diels Alder Cycloaddition of ethylene and cyclobutadiene. In both cases, the structures of the transition states were determined and compared to the reactants involved. Electron flux and its effect on the strength of the bonds involved was looked at and in the case of the Diels Alder reactions, it was possible to determine which of the endo or exo product was in fact the major outcome.

Operations such as optimisations, frequency analysis, intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) determination and activation energy calculations will be performed throughout this computational lab module, all of which will be used to gain a better understanding of the molecular orbital (MO) interactions of the frontier orbitals orbitals involved in the transition states created. From the data obtained it is also possible to determine thermochemical values to a highly accurate degree. With all these tools at our disposal it is possible to provide explanations as to why certain products that were expected to dominate in fact turn out to be the minor product and vice versa.

Al of this combined provides an excellent means of exploring the stepwise properties of a reaction and the structures of transition states to complement physical data from the lab. Furthermore, computational chemistry had the added advantage of allowing the user to determine many physical and chemical properties of highly toxic compounds without having to come into direct contact with them.

The Cope Rearrangement

Overview

This part of the report has the role of introducing the reader to the various computational operations involved in the analysis of reaction mechanisms and transition states. The Cope Rearrangement was first discovered by Arthur C. Cope, whose work was first ublished in 1940. His work still remains an extensively researched class of organic reactions and in this instance the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene will be explored. The reaction mechanism consists of a [3,3]-sigmatroptic shift, a type of pericyclic reaction.

A pericyclic reaction is one in which bonds are made or broken in a concerted cyclic transition state, i.e. without the formation of any intermediates. A sigma-tropic shift specifically involves the migration of a bond, for example a σ bond between two carbons, or a C-H σ bond. The case of a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift, as is the case for the Cope Rearrangement discussed, involves the particular shift of a C-C σ bond that has the result of shifting the allyl bonds. The reaction may proceed via two different transition states - a chair or a boat. It has also been suggested that the transition state can proceed via a 1,4-diyl or a loose aromatic transition state[1], but for the purposes of this exercise we will stick to the di-allyl method in which the fragments can be individually optimised.

In this section of the report, analysis will be carried out on both the chair and boat transition state of the 1,5-hexadiene Cope Rearrangement. Frequency analysis and intrinsic reaction coordinates will be generated to work out the activation energy of the reaction and which conformers of 1,5-hexadiene are involved in such a reaction. Using MO analysis, it will also be proven that a [3,3]-sigmatropic shift of 1,5-hexadiene proceeds thermally via Hückel topography, with a total count of 6π electrons involved in the pericyclic reaction.

Calculating 1,5-hexadiene's Lowest Energy Conformation

Optimisations of each Conformer

The role of molecule optimisation is to find the energy minimum of a molecule by solving Schrödinger's equation multiple times at different interatomic distances. The minimum energy will correspond to the energy at which a perfect, stable equilibrium exists between nuclear repulsion and electrostatic attraction, and will determine the bond lengths of the molecule. By optimising the various conformations of 1,5-hexadiene it is possible to determine the conformer with the lowest energy minimum that will consequently be used for the determination of the mechanism for the Cope Rearrangement.

1,5-hexadiene is able to adopt two principal conformations across the four central C-C bonds, either as anti peri planar or Gauche. The terminal diene groups were then adjusted to have varying dihedral angles with respect to the central conformation, thereby altering the point group. Each molecule's varying structure was optimised using a Hartee-Fock method with a 3-21G basis set in order to determine the lowest energy conformation. The results for the optimisations are tabulated below. (Relative energies are calculated using the conversion factor of 1 a.u. = 627.529 kcal mol-1).

| Central Conformation |

Point Group | Image of Conformer | Final Energy (a.u.) |

Energy Obtained in Reference Wiki (a.u.) |

Relative Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Log File |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-peri-planar 1 | C2h |  |

-231.68907019 | -231.68907 | 2.25 | anti hexadiene C2h |

| Anti-peri-planar 2 | C1 |  |

-231.69097045 | -231.69097 | 1.06 | anti hexadiene C1 |

| Anti-peri-planar 3 | Ci |  |

-231.69253469 | -231.69254 | 0.08 | anti hexadiene Ci |

| Anti-peri-planar 4 | C2 |  |

-231.69260212 | -231.69260 | 0.04 | anti hexadiene C2 |

| Gauche 1 | C2 |  |

-231.68771616 | -231.68772 | 3.10 | gauche hexadiene C2 |

| Gauche 2 | C2 |  |

-231.69166697 | -231.69167 | 0.62 | gauche hexadiene C2 2 |

| Gauche 3 | C2 |  |

-231.69153033 | -231.69153 | 0.71 | gauche hexadiene C2 3 |

| Gauche 4 | C1 |  |

-231.69266122 | -231.69266 | 0.00 | gauche hexadiene C1 |

| Gauche 5 | C1 |  |

-231.68961573 | -231.68962 | 1.91 | gauche hexadiene C1 2 |

| Gauche 6 | C1 |  |

-231.68916017 | -231.68916 | 2.20 | gauche hexadiene C1 3 |

It could reasonably be predicted that all anti peri planar conformations would be the conformations of lowest energy, and indeed most of the anti peri planar conformer do exhibit the smallest relative energy difference compared to the lowest energy conformer. This would be due to the least amount of steric repulsion thanks to the molecule being more spread out and linear. However, the lowest energy conformer is in fact a Gauche conformer of symmetry C1.

Looking at the anti peri planar conformer of symmetry Ci, it can be seen that the final energy obtained is -231.69253 a.u. compared to the reference value of -231.69254 a.u. This indicates that the results are extemely similar, despite a slightly greater stabilisation in the latter case. This means the structure has been very finely optimised to have perfect inversion symmetry. The obtained structure was then re-optimised using a different basis set of 6-31G with the same Hartree-Fock method. The results are tabulated below.

| Central Conformation |

Basis Set | Point Group | Image of Conformer | Final Energy (a.u.) |

Log File |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-peri-planar | 3-21G | Ci |  |

-231.69253469 | anti hexadiene Ci |

| Anti-peri-planar | 6-31G | Ci |  |

-234.55970423 | anti hexadiene opt 6-31G Ci |

As can be seen, the overall geometry does not change, nor does the point group symmetry. However, due to a larger and more powerful basis set, the final energy is lower using 6-31G than 3-21G. Nevertheless, these values cannot be compared directly, because the change in basis set implies a completely different method. It can just be observed that 6-31G is more powerful as a basis set. To investigate the effect of this basis set on the final energies of the conformers, the three conformers of the lowest relative energy were re-optimised using the 6-31G basis set. The results are displayed below.

| Conformer | Point Group | Final energy using 3-21G | Relative energy using 3-21G | Final energy using 6-31G | Relative energy using 6-31G | Log File 6-31G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauche 4 | C1 | -231.69266122 | 0.00 | -234.55933663 | 0.27 | gauche C1 opt 6-31G |

| Anti peri planar 4 | C2 | -231.69260212 | 0.04 | -234.55977105 | 0.00 | anti C2 opt 6-31G |

| Anti peri planar 3 | Ci | -231.69253469 | 0.08 | -234.55970423 | 0.04 | anti Ci opt 6-31G |

Vibrational Analysis of 1,5-hexadiene's Ci Symmetry Conformer

Vibrational analysis is useful because it not only provides the vibrational modes of a molecule, but will also confirm whether a molecule has optimised properly by the absence of "imaginary", aka negative, frequencies. If an "imaginary" frequency is present (identified by a negative sign), it suggests that the force constant of the vibration is negative. Using Hooke's Law, this would generate an imaginary frequency suggest because it would be taking the square root of a negative number.

The infrared spectrum generated by the frequency analysis of 1,5-hexadiene's Ci anti peri planar conformer is provided below, and the log file of the results can be found here. The simulated spectrum can be compared to that of experimental results. Significant differences between the spectra arise due to the fact that the method used for the simulation does not take into account anharmonicity factors. The real results displayed below are those of a neat film of 1,5-hexadiene. The most noticeable differences lie in the size of the peaks. The peaks in the simulation are extremely sharp, narrow and clean in comparison to those in the experimental data. Additionally some peaks that are mildly hinted at in the simulation are in fact very significant in the real data, e.g the peak at roughly 1800 cm-1.

|

|

Thermochemistries of the Conformers

Looking at the "Thermochemistry" segment of the log file in particular, some important data can be retrieved. Below is a tabulation of the thermochemistries associated with the three conformers of lowest energy.

| Conformer | Symmetry Label | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies |

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies |

Log file | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies |

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies |

Log file | ||

| At 0 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 0 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | ||||

| Gauche 4 | C1 | -231.539486 | -231.532647 | -231.531702 | -231.570640 | gauche C1 | -234.415745 | -234.408572 | -234.407628 | -234.447181 | gauche C1 |

| Anti peri planar 4 | C2 | -231.539601 | -231.532645 | -231.531701 | -231.570956 | anti C2 | -234.416333 | -234.409055 | -234.408110 | -234.447936 | anti C2 |

| Anti peri planar 3 | Ci | -231.539537 | -231.532564 | -231.531620 | -231.570908 | anti Ci | -234.416244 | -234.408954 | -234.408010 | -234.447849 | anti Ci |

Obtaining the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

The transition states of the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene were generated by optimising a C3H5 allyl fragment and estimating the boat and chair transition state shapes using two of these optimised fragments. The chair TS has a symmetry label of C2h and the boat TS configuration has a symmetry label of C2v. The way in which these transition states were obtained is described in the sections below.

Chair TS Optimisation

Two C3H5 allyl fragments were arranged roughly as is depicted in Figure 4, with an interatomic distance of approximately 2.2 Å between the terminal CH2 groups of each fragment. Optimisation and frequency anaylsis was then performed on this TS estimation using a default Hartree-Fock method and a 3-21G basis set. The results can be viewed in Figures 4 and 5 and the log file can be accessed here. The second optimisation of the chair TS used a Frozen Coordinates method that consisted of two parts. The interatomic distances between the terminal CH2 groups of each allyl fragment were frozen in place while the rest of the fragments were optimised to an energy minimum. In the second part of this operation, the frozen interatomic distances were solved to find their derivatives, i.e. they were optimised to a transition state. The results can be viewed in Figures 6 and 7, and the log file can be accessed here.

The results for each optimisation are compared in the tabulation below.

| Method | Basis Set | Final energy (a.u.) |

Interatomic Distance between Terminal Groups on Fragments |

C-C Bond Lengths within fragments |

Bond Angle across each fragment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | 3-21G | -231.61932247 | 2.02 Å | 1.39 Å | 120.5° |

| Frozen Coordinates | 3-21G | -231.61932181 | 2.02 Å | 1.39 Å | 120.5° |

As is evident from the results, the two optimisations have yielded almost identical results, with the exception of a slightly lower final energy using the Hartree-Fock method. Despite such similarly, the structures generated by Gaussian for each optimisations are very different. The first one, corresponding to the Hartree-Fock method, has one and a half bonds across each C-C bond (single + dotted), whereas the second optimisation just has double bonds across all C-C bonds. Structurally, the latter bond structure is incorrect with respect to the number of hydrogen atoms each carbon is bound to.

This highlights the difference between what Gaussian considers a bond, and what a bond actually is. Gaussian uses bonds merely as a structuring tool. As the Schrodinger Equation is solved several times throughout an optimisation, bonds will appear whenever the energy minimum reaches a certain threshold, arbitrarily assigned within the program. In reality, a bond is defined by the balance of the nuclear repulsion and the electrostatic attraction of the electrons between the nuclei. This means that a bond will exist firmly and with stability when an energy equilibrium between the atoms and their electron density is able to form in a stable manner. However, it does not mean that a bond is arbitrarily absent above a certain energy threshold. Electron density will still be present between two atoms, thus providing the formation a bond, despite its potentially unstable or temporary nature.

Boat TS Optimisation

Obtaining the boat transition state was not possible by means of the previous method used for the chair transition state. Instead, the optimised Ci anti peri planar conformer of 1,5-hexadiene was used as a reactant molecule. Its carbon backbone structure was carefully labelled from C1 to C6. In a second screen belonging to the same molecular group in GaussView, a second molecule of the Ci conformer was pasted, this time with its carbon backbone labelled C3-C2-C1-C6-C5-C4. This arrangement can be seen in Figures 10 ad 11. An attempt was made using an optimisation to a minimum with a QST2 method. However, the result yielded a structure that resembled the chair TS rather than the desired boat one.

Altering the reactant and product molecule structures with a central dihedral angle of 0°, and a terminal bond angle of 100°, resulted in the two structures being much closer to the transition state structure (shown in Figures 12 and 13). Optimisation to the transition state in this case is successful, yielding a boat structure with a single imaginary vibration. The results of this optimisation are tabulated below, and the log file can be found here. This clearly demonstrates the ease with which this method can determine a transition state, but also highlights its dependence on the reactant and product structures resembling the transition state very closely. The final, optimised transition state structure can be seen in Firgures 8 and 9.

| Method | Basis Set | Interatomic Distance between Terminal Groups |

C-C Bond Lengths within Allyl Fragments |

Bond Angles across Allyl Fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QST2 | 3-21G | 2.14 Å | 1.38 Å | 121.7° |

Comparison of Energies for the Boat and Chair Transition States

Below is a tabulation of the thermochemistry data retrieved from the log files of the frequency analysis of both chair and boat transition states.

| Molecule | Symmetry Label | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies |

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies |

Log file | Sum of electronic and zero-point energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal energies |

Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies |

Sum of electronic and thermal free energies |

Log file | ||

| At 0 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 0 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | At 298.15 K | ||||

| Chair TS | C2h | -231.539486 | -231.532647 | -231.531702 | -231.570640 | gauche C1 | -234.415745 | -234.408572 | -234.407628 | -234.447181 | gauche C1 |

| Boat TS | C2v | -231.539601 | -231.532645 | -231.531701 | -231.570956 | anti C2 | -234.416333 | -234.409055 | -234.408110 | -234.447936 | anti C2 |

| Reactant (Anti Ci) |

Ci | -231.539537 | -231.532564 | -231.531620 | -231.570908 | anti Ci | -234.416244 | -234.408954 | -234.408010 | -234.447849 | anti Ci |

Vibrational Analysis for the Chair and Boat Transition States

To prove that the optimisations for each transition state have run successfully, the single imaginary frequencies that were obtained for each one are provided below.

| Transition State | Method | Basis Set | Imaginary Vibration | Frequency cm-1 |

Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chair | Hartree-Fock | 3-21G |  |

-818 | 6 |

| Boat | QST2 | 3-21G |  |

-840 | 2 |

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinates (IRC)

An IRC allows a potential energy surface to be generated for a transition state as it is brought to its local minima, i.e. to the reactants and to the products. In this way, it will be possible to determine which conformer of 1,5-hexadiene corresponds most closely to each transition state. The IRCs for each transition state are given in the sections below.

Boat Transition State IRC

The boat transition state IRC was calculated over 60 steps in both directions from the energy maximum of the TS, log file may be accessed here. This yielded an almost perfect Gaussian distribution, with a slight rise in gradient at each extremity. This corresponds to the final product having being optimised, followed by a slight rise in energy again as it starts readjusting again to find a new energy minimum after having formed the two σ bonds. Nevertheless, we are only interested in the first energy minimum that was reached for the product, because this is product that most resembles the transition state. The total energy plot of the IRC and the corresponding gradient can be viewed in Figures 14 and 15, respectively. The animation for the IRC that describes the evolution for the reaction can be viewed beside the plots.

|

|

|

Chair Transition State IRC

The chair transition state IRC was obtained in the same way as the boat TS, log file may be found here. Once again, looking at the total energy plot for the IRC, we are interested in the first minimum obtained that describes the final product. The plots for both the total energy and the gradient of the IRC can be viewed, as well as the animation of the IRC.

|

|

|

What's interesting to note compared to the Diels Alder reactions discussed further on, is the fact that these are a totally symmetric IRCs. This proves that the reaction is in fact a sigmatropic pericyclic reaction due to the fact that there exists only one transition state and that the reactant and product are of equal final energy.

Activation Energies for the Cope Rearrangement

Activation energies are very important pieces of data for any reaction, leading on to an analysis of the free energies and thermochemistry involved. Thus said, it is important to have a higher level of accuracy, i.e. a greater basis set, so as to achieve results that will conform to the real experimental data more successfully. There are two ways in which this can be done. The first method would be to re-optimise the transition states and the reactant using a B3LYP/6-31G basis set, or to perform a new IRC on the optimised TS using the same higher 6-31G basis set. In this report, the latter option was chosen. The results are tabulated below.

| Structure | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | Log Files | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation Energy (a.u.) |

Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Experimental kcal mol-1) |

Activation Energy (a.u.) |

Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Experimental kcal mol-1) |

Log file 6-31G opt | Log file 6-31G IRC | |

| Chair TS | 0.073 | 45.81 | 44.69 | 0.054 | 33.89 | 33.17 | Chair TS | Chair TS |

| Boat TS | 0.08 | 50.20 | 57.16 | 0.058 | 36.40 | 41.32 | Boat TS | Boat TS |

As we can see from the IRC animation, the boat TS derives from and produces a conformer that is most similar to the Gauche conformer number 6 of symmetry C1. The chair TS derives from an conformer that most resembles the Gauche conformer number 2 of symmetry C2.

Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Overview

The [4+2] cycloaddition reaction was only fully pioneered when the products of the reaction between cyclopentadiene and quinone were correctly identified by Professor Otto Diels and his student, Kurt Alder. This discovery, published in 1928, became a historical landmark in the field of chemistry for which these two men were rewarded with a reaction that would henceforth bear their names, as well as he 1950 Chemistry Nobel Prize.

A pericyclic reaction is one in which bonds are made or broken in a concerted cyclic transition state, i.e. without the formation of intermediates during the course of the reaction. A thermal Diels Alder cycloaddition (or cycloelimination) is a specific class of pericyclics involving two π systems, a diene and a substituted alkene (also termed a dienophile). The diene contributes 4π electrons, and the dienophile 2π electrons, making a total count of 6π electrons (4n+2, where n=1). Each π system forms two new σ bonds, and because the reaction is thermal, it proceeds via Hückel topology involving only suprafacial components. An overview of such a reaction is given in Figure 18.

|

|

The term "suprafacial" means that the two σ bonds form on the same face of a π system. "Antarafacial" corresponds to the formation of bonds on opposing faces of a π system. Hypothetically, the reaction could proceed via two antarafacial components, but this is actually geometrically impossible for the example discussed.

The Diels Alder reactions considered in this part of the report are the cycloaddition of cis-butadiene with ethylene (ethene) and the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride. Examination of the frontier orbitals and the number of electrons within the system will allow the determination of whether or not the reaction occurs in a concerted stereospecific fashion (allowed) or not (forbidden), i.e. whether it conforms to the theory described in the previous paragraphs. The proposed reaction mechanisms are given in Figures 19 and 20 respectively.

The former of the mentioned reactions is as symmetric as a Diels Alder can get. Both the diene and the dienophile only have hydrogen atoms as substituents, making the exo and endo products identical. However, for the latter reaction, there is a distinct difference between the exo and endo products due to the orientation of the maleic anhydride fragment. Assess;ent as to which product is in fact more stable will take place in the following sections of the report. Because of the increased complexity of the reaction involving maleic anhydride, a more accurate way of determining the transition states will be used.

Reaction of cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

Optimisation and MO Analysis of cis-butadiene and ethylene

The geometries of cis-butadiene and ethylene were optimised to an energy minimum first using a 3-21G basis set (log file cis-butadiene, log file ethylene), and then re-optimised using a AM1 basis set (log file cis-butadiene, log file ethylene). The former yielded a final energy of -154.05394 a.u. and -77.60099 a.u., and the latter a final energy of 0.04880 a.u. and 0.02619 a.u.. Evidently, the AM1 semi-empirical method is less of a powerful basis set, but the size of the transition state to be optimised further on in the report demands a basis set of lower power due to the time constraints of the course.

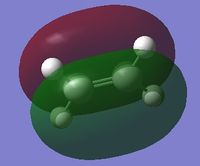

The frontier orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) were obtained for both molecules and the results are tabulated below. It can be seen that there are point nodes between the orbital lobes on the same side of the molecular plane, and planar nodes exist between lobes that are on opposite sides of the plane of the molecule. This is true for all the frontier orbitals displayed below. It is also important to note that the symmetry of interest lies with respect to the perpendicular axis to the molecule. This is the symmetry criteria that will help determine whether a reaction is allowed or not.

Optimisation and MO Analysis of the Transition State

There are two ways in which a TS can be obtained, as discussed already in the Cope Rearrangement section. Due to the fact that the endo and exo products are identical in this reaction, the method that was used is the single step optimisation of the structure to a Berny TS. The geometry of the TS was optimised using a semi-empirical AM1 method and frequency analysis was performed on the TS. The final energy for the optimisation was 0.11165 a.u., and the log file may be found here, along with its corresponding D-Space, given here: DOI:10042/22157 . MO analysis was conducted, and the frontier orbitals are given in the Figures 21 and 22. The presence of an imaginary frequency at -956 cm-1 proved the optimisation had run correctly to a Berny TS. The vibration is given below.

|

|

| Vibration | Basis Set | Motion | Frequency | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaginary | AM1 |  |

-956 cm-1 | 6 |

| First real vib | AM1 |  |

147 cm-1 | 0 |

The following is a comparison of the geometries obtained above.

| Geometry | Cis-Butadiene | Ethylene | TS Butadiene | TS Ethylene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C=C | 1.34 Å | 1.33 Å | 1.38 Å | 1.38 Å |

| C-C | 1.45 Å | n/a | 1.40 Å | n/a |

| C-H | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å |

There is a very clear evolution in the geometries within the transition state, relative to the reactants. The only bond length that remains constant throughout the reaction is the sp3 C-H bond, at 110 pm[3]. This is consistent with the normal average C-H bond length. Regarding the sp2 C=C and sp3 C-C bonds, their average lengths are 1.34 Å and 1.47 Å respectively[3]. Bond length is directly related to the bond order and bond strength of a molecule. The more electrons populate antibonding orbitals, the more the bond order decreases, thereby weakening and lengthening a bond. In the TS, the bond order of the C=C bonds both in ethylene and cis-butadiene is clearly decreasing, since the bond length is now 138 ppm relative to the reference and calculated 134 ppm. Likewise, the C-C bond that is transforming into a C=C in the butadiene (in between the C=C bonds that are disappearing) now has an increased bond order. It doesn't quite have the 134 ppm expected in the final product, but its 1.40 Å definitely indicates it isn't a single C-C bond anymore. The same concepts apply to the molecule of ethylene in which a C=C is becoming a C-C.

Looking at the frequency analysis, the imaginary vibration indicates the synchronous formation of the two new σ bonds. The first real vibration, in comparison, is merely the rotation of the two molecules in opposite directions about the same axis - it does not yield much information about the transition state; it even suggests that the formation of the bonds would be asynchronous. This reinforces the importance in obtaining the imaginary vibration. Coupled with this, the geometries recorded make it possible to reasonably state that the transition state obtained is the expected one for this Diels Alder reaction. The interatomic distances between the terminal groups of each fragment are 2.12 Å. The fact that they are both the same and that the vibration is symmetric with respect to these interatomic distances supports the theory that a Diels Alder reaction is a concerted, with the two new σ bonds forming at the same time.

As mentioned in the previous section, the symmetry of the MOs with respect to the perpendicular axis to the plane of the molecule is the most important symmetry criteria to determine whether an MO over lap will be allowed. According to theory, an allowed reaction occurs when the HOMO of one fragment can interact with the LUMO of the other fragment and vice versa. This means that the HOMO and LUMO from the two fragments must have the same symmetry, thus allowing an electron density overlap large enough to sustain the formation of two new bonding and antibonding molecular orbitals belonging to the Diels Alder product. As can be seen from the comparison of the cis-butadiene and ethylene MOs, the HOMO and LUMO from each fragment have the correct symmetry to interact with the LUMO or HOMO of the other. This confirms that the reaction of cis-butadiene and ethylene is indeed allowed, producing a concerted reaction without the formation of any intermediates. The HOMO for the TS is antisymmetric, and the LUMO for the TS is symmetric with respect to the perpendicular axis.

This being said, it is not always evident which fragment will provide the HOMO and which the LUMO for the formation of the final product MOs. In fact, the energies of the frontier orbitals are determined by the number of π electrons occupying them. The more π electrons present, the higher in energy the MO will lie. Frontier Molecular Orbital theory dictates that in this instance it is 1,3-butadiene that provides the HOMO of highest energy that will donate electrons to ethylene's LUMO. Because of the influx of electrons into what was previously a π* orbital, the bond order decreases overall with the formation of a single bond in ethylene from a double bond, consequently rehybridising ethylene's terminal 2p from an sp2 arrangement to an sp3 one. The interaction of all these MOs is described in terms of energies in the MO shown in Figure 23.

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinates (IRC)

The reaction pathways are provided below by means of transforming the TS to its local minima in both directions, i.e. towards the reactants and towards the product. Incidentally, the IRC has run in the opposite direction than is customary, i.e. from products to reactant, but this has no effect on the overall activation energy. The log file may be found here.

|

|

|

Activation Energies

Using the IRC data, the activation energies and change in Free Energy of the reaction were able to be retrieved. The results are tabulated below.

| Method | Activation Energy (a.u.) |

Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Reference computed AE[4] (kcal mol-1) |

Change in Free Energy (a.u.) |

Change in Free Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Reference computed ΔH [4] (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-empirical AM1 |

0.0370269 | 23.23 | 23.76 | -0.0856198 | -53.73 | -56.45 |

Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and Maleic Anhydride

Optimisation and MO Analysis of cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride

Cyclohexadiene and maleic anhydride were optimised first by means of a 3-21G basis set (log file cyclohexadiene, log file maleic anhydride), followed by a semi-empirical AM1 method (log file cyclohexadiene, log file maleic anhydride). The latter yielded a final energy of 0.02800 a.u. for cyclohexadiene and -0.12182 a.u. for maleic anhydride.

MO analysis was conducted, the results of which are tabulated below. Once again, the same nodal situation arises as for the previous Diels Alder reactant MOs. There are point nodes between the MO lobes on the same side of the pane of the molecule, and planar nodes for lobes on opposite sides of the molecular plane. Following on from the theory explained in the previous Diels Alder section, it can be predicted that the HOMO from cyclohexadiene will interact with the LUMO from maleic anhydride, and vice versa.

Optimisation and MO Analysis of the Transition State

Because the endo and exo products if this Diels Alder reaction are very different to each other, the Frozen Coordinate method has been used to optimise the fragments to a transition state. The Frozen Coordinates method allows for greater accuracy in determining the TS due to the fact that the fragments are first optimised about a certain intermolecular distance, and then the intermolecular distance is optimised to the bond lengths of the forming σ bonds. The geometries of both endo and exo products was optimised using the semi-empirical AM1 method, and he final energies obtained are bullet-pointed below and will be discussed further on in the report.

- Exo product: -0.05042 a.u. - (D-Space result found here: DOI:10042/22163 , frozen coord log file found here, log file found here. )

- Endo product: -0.05150 a.u. - (D-Space result found here: DOI:10042/22164 , frozen coord log file found here, log file found here. )

The imaginary vibrations obtained are tabulated below, as well as the first real vibration. The motion of the real vibration is a rotation of the two fragments of the transition state rotating about one another, highlighting the importance of the imaginary vibration that transfers vital information about the motion dynamics of the reaction path. The "flow" of electrons from the cyclohexene to the maleic anhydride makes the dienophile more nucleophilic, and the diene, which has lost electrons, becomes simultaneously more electrophilic. This reverses the situation and the electrons from the HOMO of the dienophile can now "flow" to LUMO of diene so as to complete the formation of the second bond. In the case of symmetric dienophiles such as maleic anhydride, each end of the double bond has an equal probability of being the electrophilic site in the initial charge transfer from HOMO to LUMO. In addition, once the diene and the dienophile position themselves to an interfragmental distance of 2.16 Å and 2.17 Å, the charge transfer between them allows for the formation of two new σ bonds that are generated so rapidly that there are no zwitterionic or bi-radical intermediates. The Diels-Alder reaction is thus perfectly concerted.

Once again, it is highly informative to compare the geometries of both the starting molecules and the transition state to note the length of the bonds that are theoretically being changed. The geometries are compared in the table below. The principal areas of the transition states that are of interest, are of course the regions that are involved in the concerted movement of electrons across the molecule. As expected, the two C=C bonds on the cyclohexadiene have evolved from 1.35 Å to 1.41 Å, indicating a significant decrease in bond order and π character. Conversely, the C(sp2)-C(sp2) that was located in the middle of those double bonds has shrunk from 1.45 Å to roughly 1.40 Å, indicating an increase in bond strength and bond order (loss of antibonding character). Similarly, the C=C bond on the maleic anhydride that stood at 1.35 Å has extended (or weakened) to 1.40 Å on average. Again, the influx of electrons into the bond has populated antibonding orbitals that have contributed to the weakening of the bond order and thereby bond strength.

| Reactants | Exo | Endo | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Length | Cyclohexadiene | Maleic Anhydride | TS Cyclohexadiene | TS Maleic Anhydride | TS Cyclohexadiene | TS Maleic Anhydride |

| C(sp3)-C(sp3) | 1.52 Å | - | 1.52 Å | - | 1.52 Å | - |

| C(sp2)-C(sp3) | 1.48 Å | - | 1.49 Å | - | 1.49 Å | - |

| C(sp2)-C(sp2) | 1.45 Å | 1.50 Å | 1.39 Å | 1.49 Å | 1.40 Å | 1.49 Å |

| C(sp2)=C(sp2) | 1.34 Å | 1.35 Å | 1.40 Å | 1.41 Å | 1.39 Å | 1.41 Å |

| C(sp3)-H | 1.12 Å | - | 1.12 Å | - | 1.12 Å | - |

| C(sp2)-H | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.10 Å | 1.09 Å |

| C(sp2)-O | - | 1.41 Å | - | 1.41 Å | - | 1.41 Å |

| C(sp2)=O | - | 1.22 Å | - | 1.22 Å | - | 1.22 Å |

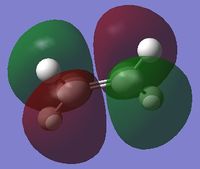

More interestingly is the interactions of the MOs within both these Diels Alder pathways that differentiates the exo so much from the endo. Below are displayed the frontier orbitals obtained for each transition state.

| Criteria | ENDO | EXO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO | LUMO | |

| MO Shape |  |

|

|

|

| LCAO Shape |  |

|

|

|

| Energy | -0.34505 | -0.03570 | -0.34275 | -0.04045 |

| Symmetry wrt to perpendicular plane |

AS | AS | AS | AS |

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinates (IRC) for the Reaction

The reaction pathway was calculated by means of an IRC, yielding the potential energy surface for the transition states and their two respective local minima, the reactant and the product. The IRC was generated over the course of 150 points, using an AM1 semi-empirical method. The results are shown below, and the log files may be found here for the endo and here for the exo.

Endo Product

|

|

|

Exo Product

|

|

|

Activation Energies for the Reaction

The activation energies were obtained from the IRC data and is recorded as follows:

| Product | Method | Activation Energy (a.u.) |

Activation Energy (kcal mol-1) |

Change in Free Energy (a.u.) |

Change in Free Energy (kcal mol-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exo | Semi-empirical AM1 |

0.0449521 | 28.20 | -0.0645331 | 40.50 |

| Endo | Semi-empirical AM1 |

0.0428218 | 26.87 | -0.0658395 | 41.31 |

From this table, we can clearly see that the endo product is the kinetic product, for it has a lower energy barrier to cross in order to overcome the activation energy. However, the exo product is in fact the thermodynamic product, which would suggest that over time, the major product would always be the exo. Nevertheless, for this reaction the endo product is the major product at all times. This means that factors other than simple kinetics and thermodynamics are at work.

Looking back final energies obtained for each product, the endo product is of lower energy than the exo product, indicating once again that it would be the major product of the reaction. However, the fact that it lies at a lower energy state than the exo product, despite the exo product being theoretically the thermodynamic product of the reaction confirms that other factors are affecting the results. The first thing to notice is the increased steric strain on the exo product of this reaction, although this should technically have already been taken into account within the optimisations and IRCs. There is another factor which has been described as having an equally important influence as sterics, and this is Secondary Orbital Overlap (SOO). SOO is a molecular-orbital-based explanation[5] as to why the endo product would be favoured, and has been defined by Wooodward and Hoffmann as "the positive overlap of a nonactive frame in the frontier molecular orbitals of a pericyclic reaction"[6]. Essentiall, SOO derives from the Salem-Klopman theory whereby the derivation of the Salem-Klopman equation will yield information about the energy lost and gained when molecular orbitals interact with one another.

The Salem-Kloppman equation is extensive, involves three heavy terms and is based on a lot of assumptions and approximations. The first term is of first order and describes the closed-shell, repulsion experienced between filled MOs interacting with one another. It is always antibonding in effect. The second term describes the Coulombic repulsion or attraction, and is important when ions or polar molecules are reacting together. The third term represents the interactions of all the filled orbitals with the empty ones of matching symmetry. it is the second order perturbation term[7].

Conclusion

The aim of this project was to highlight the use and accuracy of computational chemistry within academic research and industry by means of several basic yet highly indispensible operations. The transition states for the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene and the Diels Alder Reactions of cis-butadiene end ethene, cyclohexadiene and maleic acid. In doing so, a deeper understanding of the significance of pericyclic reactions and what a concerted cyclic transition state are was gained. It was proven that the endo product of the latter Diels Alder reaction was in fact the major product, due to an array of reason such as a mild steric factors, but principally Secondary Orbital Overlap and the effects described by the Salem-Kloppman equation. The [3,3]-sigmatropic shift was proven to be perfectly pericyclic and concerted by means of its symmetrical IRC.

I particularly enjoyed the analysis if the Diels Alder reactions and obtaining the IRCs for the reactions mentioned above and having the reaction unfold on screen in excellent detail. Thinking about the reactions from an in-depth MO point of view was also very interesting. These computional modules will certainly come in useful for future physical experiments and the extra data they will help provide in their analysis.

References

- ↑ O. Wiest, K. A. Black, K. N. Houk, J. Am. Chem., 1994, 116, 10336-7

- ↑ http://riodb01.ibase.aist.go.jp/sdbs/cgi-bin/direct_frame_top.cgi, Last Accessed 17:08, 07/12/2012

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Fox, Marye Anne; Whitesell, James K. (1995). Organische Chemie: Grundlagen, Mechanismen, Bioorganische Anwendungen. Springer. ISBN 978-3-86025-249-9

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/motm/porphyrins/introDA.html Last accessed 15:07, 07/12/2012

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona, N. J. Kiwiet, J. Org. Chem. 1987,52, 1469-1474

- ↑ Woodward, R. B.; Hoffmann, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1965, 87, 4388

- ↑ Ian Flemming, Frontier Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions, 1976 ISBN= 0471018198