Rep:Mod:2Loftus

Background

Module two of the computational lab course focuses specifically on ab initio and density functional molecular orbital techniques and their use in Inorganic Chemistry. Specifically, in more complex inorganic chemical bonding and structural analysis.

Introductory Tasks using BH3 & TlBr3

Introduction

Initially a BH3 and TlBr3 molecule was studied and manipulated using GaussView. This was completed largely as an introductory exercise to gain an understanding of the software.

Results and Discussion

Optimising BH3

The BH3 molecule was first drawn in GaussView using the element fragment database. The bond lengths were then manually changed from 1.18 Å to 1.50 Å for all B-H bonds.

This molecule was then optimised using Gaussian with the B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set, which is low accuracy, however, it takes a shorter period of time.

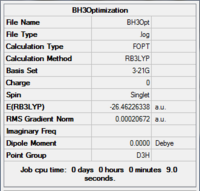

The results of the optimisation gave the optimised B-H bond length as 1.19 Å and H-B-H bond angle of 120.0 °. The result summary is shown in Fig 3.

By checking the .log file of the optimised molecule, the optimisation was confirmed as the values have converged.

Item Value Threshold Converged?

Maximum Force 0.000413 0.000450 YES

RMS Force 0.000271 0.000300 YES

Maximum Displacement 0.001610 0.001800 YES

RMS Displacement 0.001054 0.001200 YES

Predicted change in Energy=-1.071764D-06

Optimization completed.

-- Stationary point found.

The .out file was then opened and the optimization plots were then checked to see the steps of the calculation. They are not shown as they are not strictly necessary. The BH3 molecule does not show any bonds as GaussView only draws bonds for pre-defined distances. I would define the existence of a bond to be real, when the potential energy of two atoms begins to noticeably decrease due to the interaction of the other atom.

Using pseudo-potentials and larger basis sets on TlBr3

The TlBr3 molecule was drawn in GaussView similar to before. The symmetry was then restricted to D3h and the tolerance set to 0.0001 (very tight).

The TlBr3 molecule was then submitted for optimisation using Gaussian and the B3LYP method and LanL2DZ basis set, which is a medium level set.

The results of the optimisation show that the optimised Tl-Br bond length is 2.65 Å and the Br-Tl-Br bond angle is 120.0 °. File:TLBR3OPTCL.LOG

MO's of BH3

The structure of BH3 from the B3LYP/3-21G optimisation was then subjected to MO analysis using Gaussian and a more accurate 6-31G basis set. Due to the larger basis set, the job was submitted to the computing cluster (SCAN) to be calculated faster. The output file was then posted onto the Imperial D-space repository, with the following DOI. DOI:10042/to-5714

The resulting MO's were then visualised using GaussView, some examples are shown below.

| HOMO | HOMO |

|---|---|

|

|

| LUMO | LUMO+1 |

|

|

Fig 8. is an example of the LUMO+1 orbital, and is therefore unoccupied. As a result it is far more diffuse than the occupied MO's and less representative of the molecule, and hence were used less often.

NBO Analysis of BH3

Fig 9. shows graphically, the results of the Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis. The areas of low charge density are shown as green and high charge density, as maroon. The overlay numbers also show the difference in charge density over the molecule. (on the H's the values are -0.093)

By looking at the .out file in wordpad, more detailed information was shown, such as the hybridisation of the boron atoms, orbital contribution to bonds from each atom, presence of lone pairs and any orbital mixing.

For instance, taken from the .out file.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99854) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 45.36%) 0.6735* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 54.64%) 0.7392* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0001

This shows that the hybridisation of the B-H bond has 33 % s character and 67 % p character, thereby indicating the hybridisation of the bond as sp2

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

Vibrational analysis of the pre-optimised BH3 structure was carried out using Gaussian, comparing the energy with that of the optimised energy to ensure that the calculation was completed correctly, which they were.

The vibrations were then visualised using GaussView and the outputs are tabulated below.

| Vibration | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1144 | 93 | A'' |

|

|

1203 | 12 | E' |

|

|

1203 | 12 | E' |

|

|

2598 | 0 | A' |

|

|

2737 | 104 | E' |

|

|

2737 | 104 | E' |

There are only three visible peaks instead of the expected six in the IR spectrum because, vibrations 2 & 3 and 5 & 6 occur at the same frequencies and therefore overlap to give one peak each. The last peak we would expect to see at 2598 is also not visible, as there is no change in dipole moment for the vibration.

TlBr3 Calculations

Results & Discussion

The TlBr3 trigonal planar structure was first drawn and then the point group restricted to D3h with very high tolerance. This structure was then optimised using the DFT, B3LYP method and LanL2DZ medium basis set. File:TLBR3OPTCL.LOG The optimised TlBr3 was then submitted for vibrational analysis using the same method and basis set stated immediately above. File:TLBR3FREQ.LOG The reason for the same method and basis set, being used is so that the initial optimisation can be confirmed as optimised and hence at a minimum which will be shown by the vibrational analysis. If the method and basis set were changed between the calculations, there would be no relation between the two calculations as they will be fundamentally different results, due to being calculated differently. The frequency analysis will confirm that the optimisation is correct as it is effectively calculating the second derivative of the potential energy, distance graph and, hence if the resulting frequencies are all positive, the structure will have been optimised.

To ensure that the vibrational analysis had been carried out correctly, the energy given in the summary of the results was compared between the optimised structure and the vibrational analysis, they were -91.21812851 a.u. and -91.21812851 a.u. These are exactly the same showing that the two structures were exactly the same.

From the .log (output file) generated from the vibrational analysis File:TLBR3FREQ.LOG the following low frequencies were calculated by Gaussian.

Low frequencies --- -3.4213 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9367 3.9367

Low frequencies --- 46.4289 46.4292 52.1449

Diagonal vibrational polarizability:

61.4729395 61.4706198 57.8639992

This extract shows that the lowest real normal mode is 46 cm-1. The rest of the vibrations are tabulated below.

| Vibration | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

46 | 4 | E' |

|

|

46 | 4 | E' |

|

|

52 | 6 | A2'' |

|

|

165 | 0 | A1' |

|

|

211 | 25 | E' |

|

|

211 | 25 | E' |

The optimised Tl-Br bond length is 2.65 Å with a Br-Tl-Br bond angle of 120°. This bond length compares well with the literature value of 2.52 Å [1] as these values come from aqueous solutions while our calculation is modelled in the gas phase.

GaussView does not always draw bonds when they would otherwise be expected, this is because GaussView only draws bonds when predefined distances are satisfied. A bond is the attraction between two atoms which has the effect of keeping them a specific distance apart if no external forces are present. I would define the existence of a bond to be real, when the potential energy of two atoms begins to noticeably decrease due to the interaction of the other atom.

MO's of BH3

Results & Discussion

The MO diagram in Fig 12. shows the predicted MO's that would form from the combination of B and H3 AO's.

The structure of BH3 from the B3LYP/3-21G optimisation was then subjected to MO analysis using Gaussian and a more accurate 6-31G basis set. Due to the larger basis set, the job was submitted to the computing cluster (SCAN) to be calculated faster. The output file was then posted onto the Imperial D-space repository, with the following DOI. DOI:10042/to-5714

The resulting MO's were then visualised and compared to the LCAO (linear combination of atomic orbitals) orbitals which are drawn in Fig 12. The results of this comparison are shown below.

| LCAO | Symmetry | Corresponding MO | Orbital |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2e'1 |  |

LUMO+2 |

|

2e'1 |  |

LUMO+2 |

|

3a'1 |  |

LUMO+1 |

|

1a''2 |  |

LUMO |

|

1e'1 |  |

HOMO |

|

1e'1 |  |

HOMO |

|

2a'1 |  |

HOMO-1 |

Note: The small black dots are place holders and not AO's

As we can see from the LCAO and computed MO comparison, there is very little difference between the two. The only changes being that the overlap between the AO's lead to MO's which are more de-localised over the whole molecule. This shows that the accuracy of qualitative MO theory is particularly good for less complex molecules making it an extremely useful technique to study bonding.

Cis & Trans Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2

Introduction

Cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 were studied using Gaussian looking specifically at the vibrational spectra of each to compare the differences in structure.

Results & Discussion

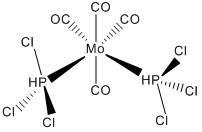

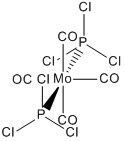

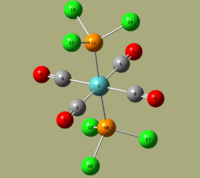

To begin with both cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 were drawn in GaussView using the octahedral Mo fragment. To this four carbonyl ligands were added from the R-group fragments. Finally PCl3 groups were then added in the cis and trans configurations, instead of the PPh3 groups as these would take too long to calculate with Gaussian, because they have far more atoms and hence electrons than a single chlorine. Chlorine still works well in this situation as it is quite a large atom making it a good compromise.

The resulting complexes are drawn right as examples.

Each isomer was then submitted to low level optimization with Gaussian using B3LYP method and LANL2MB basis set to roughly improve the geometry. Additionally "opt=loose" was added to the additional keywords to allow for the less accurate basis set to converge. The resulting output files are; cis: DOI:10042/to-5859 trans: DOI:10042/to-5860 .

These initial optimisations were then opened in GaussView and the PCl3 groups rotated to give a better starting point for the next more accurate optimisation. To do this for the cis isomer, the PCl3 group was rotated so that the one P-Cl bond was parallel to a Mo-C bond. The remaining PCl3 group was then rotated to be parallel to the opposite Mo-C bond. This is shown right.

The trans isomer was edited so that the two PCl3 were eclipsed to each other when looking down the P-Mo-P bond, again shown right.

To do each of these rotations of the PCl3 groups the di-hedral angle was edited between the P-Cl bond and a Mo-C bond so that it was equal to zero. The other P-Cl groups were then equally edited so that they had the same angle as prior to the change in the P-Cl bond.

With the manual edits, the files were then sent for a more precise optimisations using B3LYP method and LANL2DZ basis sets. The "opt=loose" was removed and the more precise convergence criteria "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" added in its place. Outputs; cis: DOI:10042/to-5869 trans: DOI:10042/to-5868

These optimisations were then sent for the last optimisation with same parameters as previously, however with "extrabasis" added to the additional keywords section and the below text added to the .gjf file before it was sent.

(blank line)

P 0

D 1 1.0

0.55 0.100D+01

****

(blank line)

The reason for this addition was to take into account that phosphorus is often hypervalent and therefore only taking into account s and p orbitals as in LANL2DZ, is not really good enough. Outputs; cis: DOI:10042/to-5870 trans: DOI:10042/to-5871

After this final optimization, the structures were then sent for frequency analysis using the same additional keywords "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9 extrabasis" as before and same editing of the .gjf file. Outputs; cis: DOI:10042/to-5902 trans: DOI:10042/to-5901

By checking all of the low frequencies calculated and stated in the output file the structures are indeed at minimums and optimised as there are no negative frequencies.

Geometry

To ensure that the optimisation has produced a reasonable structure, some physical characteristics were compared with known literature values, such as bond lengths and angles. These have been tabulated below.

These literature values come from the similar, however, not exactly the same molecule Mo(CO)4(PEt3)2. Even though it is not exactly the same the results will still be similar and useful to make comparisons with.

| Bond Length | Calculated value / Å | Literature value / Å [2] |

|---|---|---|

| Mo-P10,11 | 2.48 | 2.52 |

| Mo-C2,4 | 2.05 | 2.04,2.02 |

| Mo-C 6,8 | 2.02 | 1.97,1.98 |

| C6,8-O | 1.18 | 1.14 |

| C2,4-O | 1.17 | 1.13,1.14 |

| Bond Angle | Calculated value / ° | Literature value / ° |

| P10-Mo-P11 | 94.3 | 97.5 |

| P11-Mo-C6 | 175.8 | 177.4 |

| C2-Mo-C4 | 178.7 | 177.5 |

| C2-Mo-C8 | 89.1 | 89.6 |

Almost all of the bond lengths when compared to literature are very similar, generally there is less than 0.04 Å. This is in very good agreement. The bond angles are also very consistent with the literature being not out by more than 4° at most. These small deviations can be attributed to the fact that they are not exactly the same complexes being compared and that this is not the most accurate basis set used.

Again, the exact molecule could not be found and therefore these results come from, Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2

| Bond Length | Calculated value / Å | Literature value / Å [3] |

|---|---|---|

| Mo-P10,11 | 2.42 | 2.50 |

| Mo-C2,6 | 2.06 | 2.02 |

| Mo-C 4,8 | 2.06 | 2.01 |

| C-O | 1.17 | 1.17 |

| Bond Angle | Calculated value / ° | Literature value / ° |

| P10-Mo-P11 | 176.7 | 180.0 |

| P11-Mo-C4 | 90.0 | 92.0 |

| C2-Mo-C6 | 180.0 | 180.0 |

| P11-Mo-C6 | 88.4 | 87.2 |

The results of the geometry comparisons with literature for the trans isomer are also very good and in almost all regards compare well with only small deviations. The small deviations can also be attributed to the fact that they are not exactly the same complexes being compared and that this is not the most accurate basis set used.

Frequency

From the frequency analysis there were no negative or very low frequencies which show thata the optimisation was indeed good. Comparisons were then made between the C=O vibrational frequencies and literature.

| Vibration | Calculated Freq / cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Freq / cm-1 [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | 1605 | 1867 | |

| 1942 | 813 | 1896 | |

| 1952 | 588 | 1924 | |

| 2019 | 545 | 2026 |

| Vibration | Calculated Freq / cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Freq / cm-1 [5] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 1606 | 1889 | |

| 1940 | 1606 | 1889 | |

| 1967 | 6 | na | |

| 2026 | 5 | na |

The last two C=O vibrations, should have a intensity of zero in the trans complex as they would give no change in dipole if the structure was exact, due to its symmetry, however, clearly due to small deviations in the structure there is a very small change in dipole and hence they have a likewise very small intensity. This makes them practically invisible in the IR spectrum which is what we would expect. There are no literature values for these as they would not occur in the real compound as stated above.

Taking into account the expected 10 % error in the vibrational analyses, all of the vibrations match well with the literature values and as discussed above the correct number of vibrations were found for each (4 for cis isomer & 2 for trans isomer)

Energy

The energy as calculated by the final optimisations is tabulated below. I have given each energy to a greater degree than would be normal as the energy difference between the two only begins to show after about 5 sf.

| cis | trans | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy / a.u. | -623.6929 | -623.6942 |

| Energy / kJ mol-1 | -1637505 | -1637509 |

As we can see, the trans isomer has an energy which is very slightly lower than the cis isomer. The difference being 4 kJ mol-1. The reason for the difference is due to the PCl3 ligand being slightly closer to the other PCl3 ligand in the cis conformation as opposed to the trans giving, in this case only slight energy differences. If however the chlorine groups were replaced by larger groups such as PPh3 the energy difference would increase, with the trans geometry having the lower energy as the larger group would prefer to be further away from the other large group to reduce sterics.

Mini Project - Siloxane Flexibility

Introduction

Silicones (polysiloxanes) are a particularly useful class of polymers and are widely used throughout industry in medical applications, lubricants and sealants to name but a few. They have many useful properties such as high stability, gas permeability and flexibility at low temperature. Through changes in structure, such as the R group and chain linkage, these properties may also be tailored to meet the particular demands of a given use.

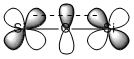

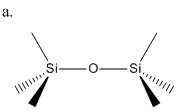

In particular, the flexibility of silicones at low temperature has been noted widely and is one of the main reasons for the large number of useful properties. Speculation into the reason for this has found to be due to the flexible Si-O-Si link. The specific reason for this Si-O-Si flexibility is either thought to be through interactions/delocalisation of the lone pairs on O with the d orbitals on Si, or the lone pairs on O with the σ* on Si. As shown in Fig 21-22.

I hope to look into the contribution of each of these interactions by looking at Si2OMe6, which should be small enough to run optimisations on while still exhibiting this overlap. Longer length chains would be preferable as this would reflect truer the nature of polysiloxanes and possibly the overlap from another oxygen either side of the silicon, however, this is not feasible for this size of project.

To compute these properties I will first optimise the structure, and then make sure its is a minima by calculating the vibrational spectra using gaussian. The last step will be to carry out NBO analysis from which hopefully any extra interaction will be viewable in the output file.

Results & Discussion

Optimisation

The molecule of Si2OMe6 (a.) was first drawn in ChemBio3D and optimised with MM2 force fields. It was then optimised with MOPAC using PM6 force fields. This basically optimised structure was then exported to GaussView as a .gjf file. At this point the file was submitted to SCAN for Gaussian optimisation using B3LYP method and LanL2MB basis set using additional keywords "opt=loose". The resuting file output was sent for further optimisation, this time using B3LYP method, LanL2DZ basis set and additional keywords "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" which increases the accuracy by reducing the convergence parameters. DOI:10042/to-6088 Using extrabasis was also tried with the same parameters as the phosphorus calculations above, changing P for Si i.e.

(blank line)

Si 0

D 1 1.0

0.55 0.100D+01

****

(blank line)

However, this caused the energy to increase slightly and therefore the result was not used any further added to the fact that I was unsure what I was really doing and if the parameters were correct for Si. (File:SiliconeMOPAClanmdzextra.out) Other optimisations were tried such as using B3LYP,6-31Gd which returned a fine optimisation (File:SiliconeMOPAC631gd.out) although the frequency came out with 2 imaginary values and was therefore not used. (File:Log 33724.out) MP2,6-311G(d,p) was also tried although this took too long to optimise and had to be cancelled.

Therefore using the optimised structure from B3LYP,LanL2DZ calculation with "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" it was then sent with the same exact values for frequency analysis DOI:10042/to-6087 and NBO analysis DOI:10042/to-6086 .

Vibrational Analysis

From the vibrational analysis the following data was obtained.

| Vibration | Calculated Freq / cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Freq / cm-1 [6][7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 926 | 256 | 860-760 | |

| 1106 | 719 | 1020 | |

| 940 | 251 | 1100 | |

| 1347 | 125 | 1260 |

The results of the frequency analysis agree well with the literature values considering the 10 % error associated with each. Especially good was the agreement of the Si-O-Si vibrations which is very close to the literature. I would think that the reason for the Si-CH3 and Si-O-C values being out is due to the chain not being long enough and therefore the Si is not bonded to another O which will inevitably affect the vibrations as the literature is for polymers.

MO's

The MO's were visualised and these are some examples.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO |

|---|---|

|

|

| LUMO | LUMO+1 |

|

|

| LUMO+2 | LUMO+3 |

|

|

The LUMO orbital is the only orbital which showed any de-localisation between the silicon and the oxygen which is what we expected, however it does not have the same approximate shape as we would expect from Fig 21-22. Possibly indicating other interactions or that the optimisation has not been detailed enough to take into account these interactions.

NBO Analysis

Looking at the NBO .out file (DOI:10042/to-6086 ) no interactions were shown as to have occurred as we would expect to see something from the oxygen lone pair and a empty d or σ* orbital on the silicon which cannot be seen at the Natural Bond Orbitals (Summary) part of the document e.g.

25. BD ( 1) C 9 - H 26 1.98847 -0.49129 90(v)

26. BD ( 1) C 9 - H 27 1.99068 -0.48983 91(v)

27. CR ( 1) O 2 1.99986 -18.91288 38(v),46(v)

28. CR ( 1) C 4 1.99939 -10.02685 44(v),73(v),74(v),72(v)

29. CR ( 1) C 5 1.99939 -10.02691 77(v),76(v),75(v),44(v)

30. CR ( 1) C 6 1.99939 -10.02686 45(v),78(v),80(v),79(v)

31. CR ( 1) C 7 1.99939 -10.02685 82(v),83(v),81(v),36(v)

32. CR ( 1) C 8 1.99939 -10.02695 36(v),86(v),85(v),84(v)

33. CR ( 1) C 9 1.99939 -10.02684 37(v),87(v),89(v),88(v)

34. LP ( 1) O 2 1.91823 -0.29103 95(v),92(v),91(v),96(v)

35. LP ( 2) O 2 1.91822 -0.29102 93(v),97(v),96(v),91(v)

A possible reason for there being no interactions could be due to the conformation of the molecule not being correct to allow the overlap between the lone pairs on oxygen and the orbitals on silicon. In a polymer there will be a far larger number of conformations of the molecule due to the amorphous nature of such polymers and these might then cause the interaction to be seen. However the NBO analysis which I have done does not give any answer to the question of whether there is any overlap between any empty orbitals.

Another reason for no interaction being shown could be that the type of calculation I have used does not take into account the possible effects of d orbital overlap in this way as there are better basis sets which add more functions and give more accurate results.

Conclusion

My results have neither proved nor disproved if there is any interaction between the O lone pairs and the Si d orbitals or σ* apart from the visualised LUMO which looked slightly delocalised. It has therefore also not been able to show if one or the other of these two interactions is predominant.

If I had extra time, I would have changed some of the R groups on the Si from methyls to more electron donating groups, which would add electron density to the Si and hence could have the effect of exaggerating any de-localisation. Another good idea (as speculated by the demonstrator) would have been to replace the O with S. The reason for this is that sulphur is a larger atom than O though still in the same group. As it is larger the orbitals would be more diffuse than O which could also increase the possible de-localisation and overlap between orbitals.

References

- ↑ J. Blixt, J. Glaser, J. Mink, I. Persson, P. Persson, M. Sandstroem, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1995, 117 (18), 5089-5104 (DOI:10.1021/ja00123a011 )

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein, B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21, 2661-2666 (DOI:10.1021/ic00137a026 )

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica. Chimica. Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171 (DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X )

- ↑ J. Shamir, A. Givan, M. Ardon, G. Ashkenazi, Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1993, 24, 101-103 (DOI:10.1002/jrs.1250240208 )

- ↑ J. Shamir, A. Givan, M. Ardon, G. Ashkenazi, Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 1993, 24, 101-103 (DOI:10.1002/jrs.1250240208 )

- ↑ P. Taranekar, X. Fan, R. Advincula, Langmuir, 2002, 18, 7943-7952

- ↑ X. Cao, L. Wang, B. Li, R. Zhang, Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 1997, 8, 657-661