Rep:Mod:2992

Module 2: Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital. Bethan Matthews

Optimisation, Vibrational Analysis and Molecular Orbital Analysis of BH3 and TlBr3

Optimisation of BH3

The molecule of BH3 was built in Gaussview and optimised (Jmol), giving the following summary (D-SPACE):

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Final Energy | -26.4623 a.u. |

| Gradient | 0.0002 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.000 Debye |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Time Taken | 26 seconds |

It was checked to see if it had run to completion, by looking at whether it had converged (log file).

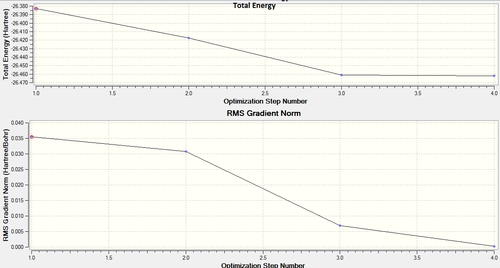

The following graphs in figure 1 show the energy and gradients for each step of the optimisation. The process terminates when the gradient is minimised (or approximately zeroed).

The energy at each step is calculated, with the aim of obtaining a minimum. The process runs until the energy decrease each time is negligible. This is shown in the gradient vs. step graph, where the final step has a gradient of approximately 0.0002 a.u. which is acceptable.

The optimised molecule of BH3 gives a computed B-H bond length of 1.19Å. This is in agreement of literature[1]. The optimal H-B-H bond angle is 120°, which fits with what is known about the structure of BH3 as trigonal planar. The advantage of using a computational analysis for the study of this molecule is the fact we can carry out theoretical calculations on a molecule which only exists as a monomer in the gas phase.

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

Performing frequency analysis can help identify whether or not we have a global minimum or not. If there are no negative frequencies calculated then the ground state configuration has been found. The vibrational analysis of the above optimised molecule (D-SPACE) gives an interesting infra red spectrum, as shown below.

The following table summarises the seperate bend and stretch modes which are obtained.

The IR shows three peaks at 1144.15, 1203.64 and 2737.44cm-1, although the vibrational analysis suggests there are six vibrational modes. It can be seen from the table that some of the modes have the same frequency and intensity, so on the spectrum they would not be distinguishable, (2 and 3, and 5 and 6). This is one benefit of the vibrational analysis. In addition to this, the peak at 2598.42cm-1 has an intensity of zero so it does not show up on the spectrum. This is because the stretch is totally symmetrical, and it cannot be detected as there is no change in dipole moment.

Molecular Orbital Analysis of BH3

The molecular orbitals (MO) for BH3 were calculated using B3LYP/6-31G basis set (D-SPACE).

| Energy | 0.192 | 0.189 | 0.189 | -0.075 | -0.357 | -0.357 | -0.518 | -6.730 |

| Shape |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Notes | Degenerate | LUMO | Degenerate, HOMO | |||||

If we compare the calculated molecular orbitals to the liner combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO), the following MO diagram is obtained. The 1s boron orbital is generally considered too low in energy to participate in bonding, and so is ignored for the purpose of this diagram.

There are no significant differences between the different methods, both giving identifiably similar orbital shapes. This leads to the conclusion that for this molecule, each approach is valid. The LCAO approach is merely qualitative, but the computed MOs have an energy assigned. This is much more useful when trying to consider the ordering of the orbitals and their relative stabilities.

NBO Analysis of BH3

The NBO analysis of BH3 gives a charge distribution as shown in Figure 3. The value of the boron atom is 0.332eV, and the hydrogens each have a value of -0.111eV. This is reasonable, as the boron is highly electron deficient, only having six valence electrons in this molecule. This electron deficiency is why it acts as such a good Lewis acid, and also why it prefers to dimerise to B2H6. These charges cancel out over all, leaving the molecule neutral.

From the .log files, we can look at the type of bonds that are formed. We expect an sp2 hybridisation, so the bonding orbitals on the boron atom are expected to be approximately 33% s-character and 66% p-character. The hydrogen atoms are expected to bond through s-orbitals.

| Atom | Contribution to bond (%) | s-Character (%) | p-Character (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B | 44.48 | 33.33 | 66.66 |

| H | 55.52 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| LP | Not included | 100.00 | 0.00 |

Optimisation of TlBr3

The molecule of TlBr3 was built in Gaussview and optimised (D-SPACE) to give a summary as shown below in table 4. (Jmol). As it is a relatively large molecule, with a total of 151 electrons, we have to use a pseudopotential. This models the core orbitals of the atoms, as they are not majorly involved in the bonding.

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Final Energy | -91.2181 a.u. |

| Gradient | 0.0000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.000 Debye |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Time Taken | 24 seconds |

This optimisation gave a Tl-Br bond length of 2.65Å, and a bond angle of 120°.

Vibrational Analysis of TlBr3

The vibrational analysis of the above optimised molecule gives an interesting infra red spectrum, as shown below.

The following table summarises the seperate bend and stretch modes which are obtained.

Again we can see degeneracy of the vibrations, modes 1 and 2, and 5 and 6. This shows up as one peak on the IR spectrum. Again the lack of a change in dipole in the fully symmetric stretch at mode 4 results in a zero intensity peak and therefore a lack of its presence on the IR spectrum. There are no negative frequencies shown, which suggests we have found the ground state configuration. If we look at the low frequencies in the .log file, we can see that although there are some negative frequencies, they are all more positive than -10cm-1 and can therefore be neglected.

Low frequencies --- -3.4213 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9367 3.9367 Low frequencies --- 46.4289 46.4292 52.1449

Cis- and Trans- Isomers of [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

Note that Gaussview removes some bonds, where it cannot interpret the lengths correctly, thinking they are too long to be actual bonds. This short coming has been ignored, and it primarily occurs in the P-Cl bonds and occasionally in the Mo-P bonds. This is because Gaussview has a list of mainly organic bond lengths, and the bonds created in this molecule do not fit within these parameters. As chemists we represent a bond as a line, and this line can be as long or as short as we draw it. However, Gaussview does not understand this, and has to assign bonds based on the separation distance between two atoms. This is vaguely unhelpful, as for inorganic compounds the bonds do not always follow this ideal distance, especially in transition metals. Technically the bond shouldn't be based too much on the separation distance, as there are other factors which come into play when determining the length of the bond, (electrons being present to form the bond, the ratio of the number of atoms to the number of electrons available to form the bonds etc.) This problem also manifests itself in the sulphuric acid mini project, where you would conventionally draw the molecule with 2 S=O and one S-O-. This causes a problem with the bond lengths, as they are actually resonance forms, with a bond length sort of in between a single S-O and a double S-O.

Optimisation of Trans-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

The molecule was primarily optimised using a loose convergence limit and a relaxed basis set, in order to obtain an optimised molecule which could then be further be optimised, after a few manual manipulations to the molecule, which computational methods fails to perform. Note that Gaussview removes some bonds, where it cannot interpret the lengths correctly, thinking they are too long to be actual bonds. This short coming has been ignored, and it primarily occurs in the P-Cl bonds and occasionally in the Mo-P bonds.

| Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANLZ2MB | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -617.522 a.u. | -623.576 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.0000 a.u. | 0.0000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | 0.3053 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Time Taken | 7 minutes, 29.8 seconds | 40 minutes, 27.4 seconds |

| D-Space | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 |

| Jmol | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 |

From this optimised structure, we can look at the bond angles and bond lengths.

| Bond | Computed Bond Length /Å | Bond | Computed Bond Angle /° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P | 2.44 | P-Mo-C | 90 |

| P-Cl | 2.24 | ||

| Mo-C | 2.06 | C-Mo-C | 179, 90 |

| C=O | 1.17 |

These bond angles are as expected for an octahedral geometry. The angles are only quoted to the nearest whole number due to accuracy problems, which explains the angle of 179° rather than the ideal of 180°. This can mainly be attributed to the computational weaknesses, and maybe increasing the accuracy of the basis set and pseudopotentials will allow for more idealised values.

Vibrational Analysis of Trans-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

One way to identify which isomer you have is to use IR spectroscopy, but this is only useful if the two isomers have distinctly different spectra. The frequency analysis was run using the same basis set and method as the second optimisation, important as we don't want to induce any other changes. By comparison of the details from the summary below and the one above, we can confirm that we are indeed running frequency analysis on the fully optimised molecule rather than the partially optimised molecule.

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -623.576 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.0000 a.u. |

| Imaginary Frequency | 0 |

| Dipole Moment | 0.3053 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Time Taken | 30 minutes, 24.4 seconds |

| D-SPACE | Frequency Analysis |

The IR spectrum is shown below.

The carbonyl stretches are not degenerate in this molecule, although we expect them to be, due to the high symmetry of the molecule. The table below summarises the relevant stretches. Only one peak is expected, due to the fact all carbonyls are axial and therefore the same.

Optimisation of Cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

| Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANLZ2MB | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -617.525 a.u. | -623.577 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.0003 a.u. | 0.0000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 8.4926 Debye | 1.3093 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Time Taken | 10 minutes, 11.3 seconds | 1 hour, 4 minutes, 40.9 seconds |

| D-Space | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 |

| Jmol | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 2 |

From this optimised structure, we can look at the bond angles and bond lengths.

| Bond | Computed Bond Length /Å | Bond | Computed Bond Angle /° |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-P | 2.51 | P-Mo-C | 176, 89 |

| P-Cl | 2.34 | ||

| Mo-C | eq=2.06, ax=2.01 | C-Mo-C | 178, 90, 87 between two equatorial |

| C=O | 1.17 |

These angles are approximately what are expected from an octahedral molecule. The two PCl3 ligands cause a slight compression of the two equatorial carbonyl ligands, which is reflected in the angle of 87°, which is slightly lower than the ideal ligand of 90°.

Vibrational Analysis of Cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

| Calculation Type | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -623.577 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.0000 a.u. |

| Imaginary Frequency | 0 |

| Dipole Moment | 1.3090 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Time Taken | 31 mintues, 5.8 seconds |

| D-SPACE | Frequency Analysis |

The IR spectrum is shown below.

The table below summarises the relevant stretches. We expect two types of peak, one for the axial carbonyl and one for the equatorial carbonyl.

Comparison of Cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] and Trans-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]

From the above results, you can see that the cis isomer is slightly more stable than the trans isomer. The energy difference is sufficiently small enough (2.63kJ mol-1) that the isomerisation can take place at room temperature. This is agreeable with the process described in literature.[2]

In the trans form, the PCl3 groups are far apart, and there is little steric hinderence. In comparison, the cis form has the PCl3 groups next to each other, which causes a destabilisation. However, this is not in agreement with the data calculated above, so there must be another angle to look at. If you consider the magnitudes of the trans effect of each group, this can help explain it. The trans effect of the carbonyls is slightly smaller than the PCl3 groups, and therefore stabilise the trans group when they are placed opposite each other. If the PCl3 groups are opposite each other, this causes a relative destabilisation. You can alter the order of stability of cis and trans isomers by changing the PCl3 ligand for a ligand with a smaller trans effect.

Sulphuric Acid

The molecules were first optimised using a low accuracy basis set to give the follow summary.

| Quality | H2 | S2O62- | S2O6H2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G | 3-21G | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 | 2- | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -1.17 a.u. | -1240.90 a.u. | -1242.09 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.000 a.u. | 0.000 a.u. | 0.000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | 0.0000 Debye | 0.0071 Debye |

| Point Group | D*h | C1 | C1 |

| Time Taken | 12s | 1m54.5s | 2m57.9s |

| D-SPACE | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 1 |

| Jmol | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 1 | Optimisation 1 |

Obviously, these energies are clearly quite high, so for the next optimisation, which was done with a more accurate basis set etc, the molecule was rearrange slightly, as seen in the next Jmols.

| Quality | H2 | S2O62- | S2O6H2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 2- | 0 |

| Spin | singlet | singlet | singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -1.17 a.u. | -471.17 a.u. | -472.28 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.000 a.u. | 0.000 a.u. | 0.000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.0000 Debye | 0.0003 Debye | 3.6255 Debye |

| Point Group | D*h | C1 | C1 |

| Time Taken | 11.3s | 1m57.1s | 9m24.8s |

| D-SPACE | Optimisation 2 | Optimisation 2 | Optimisation 2 |

| Jmol | Optimisation 2 | Optimisation 2 | Optimisation 2 |

From these optimisations, the bonds disappeared, which is just Gaussview telling us the bonds are not perfectly matched to his list of ideal organic bonds. However, in S2O62- there are a number of equivalent resonance structures, which results in these bonds all appearing equivalent (1.616Å). In S2O6H2 there is a difference in the bond lengths between the S=O(1.59Å) and the S-O (1.77Å). These are both as expected, which is quite a useful computation, as occasionally the methods do not use any sort of chemistry and just take the structure as drawn.

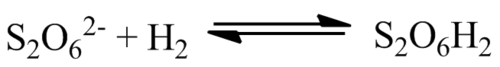

In terms of the energy change of the equilibrium shown above: The left hand side has a total energy of 101.62kJ mol-1, the right hand side has a total energy of 123.14kJ mol-1. This gives an energy change of forward - backwards = 21.52kJ mol-1. These values were taken from the thermochemistry sections of the log files for the frequency calculations. (H2 S2O62- S2O6H2 This calculation shows that the molecule prefers the dissociated state, although the energy change is relatively low, so the reaction is probably in equilibrium at room temperature (or at least only just above).

If we obtain the LUMO values for S2O62- and S2O6H2, we can see that the S2O6H2 has a LUMO which is lower in energy.

|

|

| 0.13 | -0.25 |

This is because the effect the negative charge has on the energy levels is to raise them slightly. We can also look at the structures of the MOs. If we first examine the S2O62- LUMO: The main S-S bond is strongly antibonding in character, this is likely to cause a large destabilisation, contributing to the higher energy of the MO. In contrast, the oxygens all bond to the sulphur in a normal bonding way, this allows some weaker through-space bonding-type interactions between all the oxygens, which causes a slight stabilisation effect. There are 5 obvious nodes in this moleculur orbital. If we compare this to the S2O6H2 LUMO, there is a similar anti-bonding in character S-S bond. Again, the oxygens all have the same bonding orientation, allowing through-space bonding-type interactions, as above. There is also the fully bonding interaction between the H and the O, again, a favourable interaction. This MO is more negative in energy, as it is not an anion.

If we consider the other MOs for S2O6H2, the six which are lowest in energy are all centred on the oxygen atoms, which is to be expected, as the higher electronegativity of the oxygen atoms than the sulphur atoms causes the MOs to be lower in energy. MO 7 is the completely bonding orbital which is relatively boring and also expected. If we jump to MO 13, this MO is quite intersting. The S-S bond is total bonding in character, but all the S-O interactions are anti-bonding in character. This is clearly quite a large destabilisation effect, but if you consider the weaker through-space interactions, there are number of bonding character interactions, which help to counteract the destabilisation effect. There is also the O-H bond, which in this MO is bonding in character. In fact, the O-H bond is bonding in character (or not part of the MO) all the way through the lower energy bonding orbitals, it's not until the really high energy MOs are examined that we find the O-H bond being anti-bonding in character.