Rep:Mod:1992

Module 1: The basic techniques of molecular mechanics and semi-empirical molecular orbital methods for structural and spectroscopic evaluations. Bethan Matthews

Hydrogenation of a Cyclopentadiene Dimer

This experiment uses Chem3D's MM2 force-field to model two possible dimers of cyclopentadiene and to optimise their geometries and energies. The values are then compared in order to allow us to draw conclusions about the relative thermodynamic stabilities of these products. MM2 force-field is then used again to compare two possible products of mono-hydrogenation of the cyclopentadiene dimer, and again to draw conclusions about the preferred thermodynamic product of the hydrogenation process.

Cyclopentadiene is a very common molecule, and has extensive use as a ligand. It readily undergoes a dimerisation process via a 4πs + 2πs Diels-Alder reaction at room temperature to either the exo 1 form or the endo 2 form, as shown in figure 1.

The cyclopentadiene dimer can exhibit two forms, the exo form, 1, or the endo form, 2. These two differ in energy slightly, causing one to be favoured over the other. Thermodynamically, dimer 1 is preferred by 8.88kJ mol-1, as implicated by the data shown in Table 1. However it is found that dimer 2 is formed exclusively, leading to the conclusion that the dimerisation process is a kinetically controlled process. This means that the activation barrier to the formation of dimer 2 is smaller than that to the formation of dimer 1, and therefore is formed quicker. There is not enough energy in the system for the possible products to equilibrate, and the kinetic endo product dominates over the thermodynamic exo product. However, it is also noted that it is possible for one product to be both the endo and exo forms, although that is not the case in this reaction.

| Dimer | Energies /kJ mol-1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | |

| Dimer 1 | 5.38 | 86.10 | -3.51 | 32.047 | -5.93 | 17.71 | 1.58 | 133.37 |

| Dimer 2 | 5.23 | 87.23 | -3.50 | 39.79 | -6.46 | 18.07 | 1.87 | 142.25 |

The Jmol files are available here: Dimer 1, Dimer 2.

From the table, it can be seen that the most significant contribution to the higher energy of the endo form 2 is the torsional strain, the others have negligible differences. The proximity of the two carbon atoms shown in Figure 2 causes 1,4 strain. There are two occurrences of the 1,4 strain, the other occurs in the two corresponding carbons "behind" the highlighted carbon atoms. This does not occur in the exo form, due to the different relevant orientations of the norborene and cyclopentene rings. As the kinetically favoured endo product has a lower activation barrier, it must also obviously have a lower energy transition state than the exo product. This is caused by the secondary orbital interactions possible when considering the different approaches of the two cyclopentadiene monomers. The secondary orbital interactions are favourable, and cause a stabilisation of the transition state in which they occur. The transition state is therefore lower in energy, and is a more accessible reaction pathway. In order to allow dimer 1 to predominate, the reaction would need to be carried out at a higher temperature, and allowed to fall into equilibrium over a longer period of time.

|

|

The exo 1 form has no opportunity for secondary orbital overlap, as the top cyclopentadiene molecule is not in the correct orientation to allow the required proximity needed. This is simply because there is nothing above the orbitals in the bottom cyclopentadiene monomer for them to interact with. The dotted lines show the two sigma bonds which are to be formed in the cycloaddition process for this dimer. The endo 2 form has the correct relative orientation of the two monomers to allow secondary orbital interactions. This results in a stabilisation of the transition state, caused by the secondary orbital interactions, and hence a lowering of the energy of the transition state. The activation barrier for the endo process is smaller than for the exo form which has no secondary orbital interactions, and is therefore formed more quickly — the kinetic product.

If we apply the same analysis to the products obtained from hydrogenation, as shown in Figure 1, we can determine which of the products is likely to be formed first.

| Dimer | Energies /kJ mol-1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | |

| Dimer 3 | 5.22 | 80.15 | -3.49 | 46.34 | -6.87 | 24.25 | 0.68 | 146.29 |

| Dimer 4 | 4.59 | 60.77 | -2.30 | 52.29 | -4.48 | 18.88 | 0.59 | 130.34 |

The Jmol files are available here: Dimer 3, Dimer 4.

The hydrogentation product 4 is thermodynamically more stable than 3 by 15.95kJ mol-1. This suggests that product 4 is formed under equilibrating conditions, although we cannot rule out the fact that product 3 may be the kinetic product. From the comparison of the values above, the most significant contribution to the higher energy of product 3 can be attributed to the "Bend", or more formally, the total angular strains of the molecules . If we consider the bond angles at the alkene carbons, in product 3 the angle is 107.64°, whilst in product 4 the angles are 112.4° and 113.0°, as calculated by Chem3D. As the hybridisation at the carbons in question is sp3, the optimal angle is 120°. Any deviation from this value will cause a strain, which destabilises the molecule, Furthermore, the larger the deviation, the larger the destabilisation will be. As you can see from the thermodynamic values and the angles provided, product 3 is more destabilised and is higher in energy. This leads to the conclusion that product 4 will be formed preferentially under thermodynamic conditions. However, this does not allow any conclusions to be made about the preferred product under kinetic control, as we do not know anything about the transition states or the relative energies of activation.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol.

Taxol is an important drug in the treatment of ovarian cancer.[1] Its synthesis was proposed by Paquette[2] an intermediate being one of two isomers, one with the carbonyl group up, 9, and one with the carbonyl group down, 10. These are the intermediate species that will be focused on here. It is documented that the produced isomer converts into the other form after being left to stand for a while. This would suggest (without analysis of actual data) that the product formed in the synthesis is the kinetic product, and after being left the molecule falls into equilibrium and the thermodynamic product then dominates, (see above for discussion on thermodynamic vs. kinetic).

To confirm these suspicions, analysis of the optimal thermodynamic data is required. The following data were accumulated by using MM2 force-field to calculate the minimal thermodynamic energies in Chem3D. Care had to be taken in order to ensure that the global minima were calculated, rather than a local minima, as the MM2 force-field cannot tell the difference, and the molecule had to be manipulated manually to find two of the minima. A molecule with more than one possible isomer will have one or more minima in the energy curve, and it is important to ensure you have not calculated the same one twice and assumed it is due to two separate isomers.

| Atropisomer | Energies /kJ mol-1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | |

| Intermediate 9 | 12.08 | 72.29 | 1.98 | 86.23 | -3.74 | 60.15 | -7.15 | 221.79 |

| Intermediate 10 | 11.33 | 49.49 | 1.64 | 95.72 | -8.32 | 59.99 | 8.36 | 201.49 |

The Jmol files are available here: Intermediate 9, Intermediate 10.

Thermodynamically, intermediate 10 is preferred over intermediate 9 by 20.30kJ mol-1. This shows that it is possible in this reaction for one product to be formed initially, then to convert into another atropisomer over time, but only if the product formed initially is intermediate 9. So in conclusion, intermediate 9 is the kinetic product, and intermediate 10 is the thermodynamic product. On closer evaluation of the values, it is seen that there is significant contributions to the higher energy of the intermediate 9 from the "Bend" and "Torsion" energies, with a slightly smaller effect caused by the "Non-1,4 VDW" interactions. Furthermore, there are variations on the structure, with the cyclohexane ring in twist-boat and boat conformers, these are higher in energy than the chair structure, and so their analysis is disregarded for this study.

The "Bend" energy (and technically the "Torsion" energy too) is more accurately the angular strain, caused by any deviations in structure from the ideal angles, as defined by the hybridisation of the atom in question. The analysis of how a double bond next to a bridgehead affects the angular strain and stability of a molecule has been extensively performed by Maier and Schleyer [3]. Olefin strain can be calculated as follows: Olefin Strain = Parent hydrocarbon strain - olefin derivative strain Both the parent hydrocarbon and the olefin derivative have to be in their most stable form for the above rule to be used. If you look at the equation, you can see that to go from the olefin derivative to the parent hydrocarbon a hydrogenation reaction must occur. So the olefin strain is related to the energy change when the molecule has been dehydrogenated. The ideal angle for an sp2 carbon in an olefinic bridgehead is 120°, and in an sp3 carbon in a saturated bridgehead is 109.5°. If the angle formed in intermediate 10 is studied, the angle is 123° (120° ideal), whereas in the hydrogenated form it is 115° (109.5° ideal). Clearly this forms more angular strain in the saturated form, hence the addition of a double bond adjacent to the bridgehead increases the stability of the compound. The same trend is seen when comparing intermediate 9 and its hydrogenated derivative. This is an example of a hyperstable alkene, as described in Maier and Schleyer's findings, where the loss of this stability (e.g. on functionalisation) causes an increase in the optimal thermodynamic energy of the molecule.

Another factor causing the instability of intermediate 9 is the "Non-1,4 VDW" energies. This is caused by repulsive interactions which occurs at distances of less than approximately 2.1Å. In intermediate 9 there is two instances of hydrogen-hydrogen interactions of less than 2.1Å, at 2.08Å and 2.09Å. However, in intermediate 10 there was only one, at 2.08Å. This means that there is more destabilisation due to repulsive Van der Waals in intermediate 9 than in intermediate 10, and this causes a significant impact on the overall thermodynamic attributes of the molecule.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

This section looks at how we can anticipate the spectroscopic data by considering the influence of the molecule's electronic properties. This involves considering the electrons of the molecule, and the shapes of the relevant orbitals. This can give us an idea of where the incoming molecule may attack, by considering the areas of high and low electron density. It is obvious that an electrophile will attack an area of high electron density, and a nucleophile will attack an area of low electron density, but if there are two 'classically considered' bonds which may both be of high electron density (in this case two alkenes), which one is more likely to undergo attack? The molecule does not have a plane of symmetry allowing the equivalence of the two alkenes, the only plane of symmetry results in the two ends of each alkene being symmetrical.

The MM2 force-field method is useful for first optimising the molecule and checking the global minimum has been located, although in order to model the actual frontier orbitals we need to use MOPAC/PM6, which is a more superior method, (although slightly more time consuming). The MM2 force-field of compound 12 gives the following data:

| Energies /kJ mol-1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy |

| 2.59 | 19.82 | 0.17 | 32.05 | -4.47 | 24.24 | 0.47 | 74.87 |

The Jmol files are available here: Compound 12

The MOPAC/PM6 method determines the shape of the orbitals for compound 12, they can be seen in figure 7. This method does manage to discriminate between the alkenes, which is useful as they are not equivalent. To examine the reactivity of the alkenes, the HOMO has to be looked at to find out which alkene is more nucleophilic (to undergo an addition reaction with another electrophile. It can be seen that the HOMO is more localised on the chlorine-side alkene, meaning higher electron density in this area, and therefore a more nucleophilic alkene than the hydrogen-side alkene. For example, this alkene would undergo hydrogenation to give the product 13 rather than the alternative hydrogenated product.

From the above modelling methods, for addition of dichlorocarbene (:CCl2), which is an electrophile, attack is favoured on the chlorine-side alkene. This is as documented in reaction data, so this proves to be an effective and accurate method of modelling the regioselectivity of electrophilic attack.

Running B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)gives the IR data for the compound 12 (D-Space) and the monoalkene product 14 (D-Space) (with the H-side alkene hydrogenated instead). The table below summarises the stretches relating to the C-Cl bond. The typical values for a C-Cl stretch are 785-540cm-1.[4]

From the data, you can see that when the H-side alkene is removed, the C-Cl stretch increases in frequency slightly. This suggests that there is an interaction in compound 12 that causes the decrease of the C-Cl stretch, between some part of the C-Cl bond and the H-side alkene bond. The lower frequency of the C-Cl stretch in compound 12 means the σ bond is weaker here than in product 14. Looking at the orientation of these two bonds in relation to each other, it is potentially possible that the C-Clσ* gains a slight degree of electron density from the H-side alkene, and on populating the σ* orbital, the σ weakens slightly and hence decreases the C-Cl stretch frequency. This is the only remarkable difference in frequencies, the other differences are relatively neglibible, which adds to the credibility of the above suggestion of electron density donation.[5]

This method proved to be a useful way of obtaining a potential IR spectrum, there are no issues with purity, too much nujol etc, only potential issues in the calculation of the frequencies, although this is a relatively small molecule so the errors should be limited.

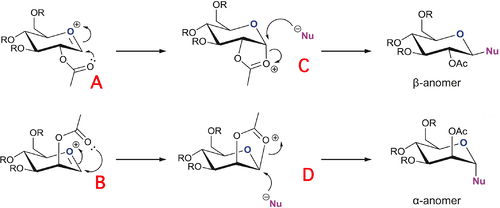

Monosaccharide Chemistry: Glycosidation

The anomer formed depends on which oxonium ion is present to begin with, the equatorial acetyl oxygen or the axial acetyl oxygen. A methyl group has been used in the place of the R group, as methyl group is relatively small and has a small number of electrons which greatly reduces the computational demand compared to an acetyl group which has roughly twice as many electrons. It also removes the problem of any H-bonding which may occur if a hydroxy protecting group is used. On running the MM2 force-field, it was found that there are two possible forms for each molecule, A, B, C and D. The optimised energies of each species was found, along with its other form, denoted A' etc. The table below summarises all the MM2 force-field optimised energies of each species, along with links to the Jmols.

| Monosaccharide Jmol | Energies /kJ mol-1 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | Bend | Stretch-Bend | Torsion | Non-1,4 VDW | 1,4 VDW | Charge/Dipole | Dipole/Dipole | Total Energy | |

| Monosaccharide A | 8.74 | 43.61 | 3.13 | 23.69 | -6.69 | 74.47 | -97.70 | 11.99 | 61.25 |

| Monosaccharide A' | 8.01 | 37.70 | 3.02 | 18.66 | -11.58 | 72.41 | -16.72 | 18.07 | 104.70 |

| Monosaccharide B | 9.27 | 39.26 | 3.09 | 31.72 | -1.06 | 77.68 | -136.68 | 18.07 | 41.34 |

| Monosaccharide B' | 7.99 | 39.80 | 2.80 | 30.28 | -19.92 | 77.16 | -7.18 | -4.33 | 126.60 |

| Monosaccharide C | 9.98 | 53.88 | 2.71 | 41.95 | -11.44 | 75.92 | -34.46 | 9.87 | 148.29 |

| Monosaccharide C' | 10.59 | 65.12 | 3.06 | 36.66 | -13.27 | 78.33 | -14.88 | 16.74 | 182.35 |

| Monosaccharide D | 9.82 | 53.89 | 2.38 | 2.18 | -12.33 | 77.81 | -44.22 | 19.54 | 141.31 |

| Monosaccharide D' | 11.57 | 68.35 | 3.22 | 36.60 | -11.98 | 78.25 | 0.87 | 9.54 | 196.43 |

In A, the acetyl oxygen is below the plane of the ring, and above in A'. In B, the acetyl oxygen is above the plane of the ring, and below in B'. In the intermediates, C and D, the X form is the cis form and the X' form is the trans form. As you can see from table 6, the X' form is always higher than the X form.

The main cause of the difference between the energies of A and A', and B and B' is the Charge/Dipole component. This is caused by the acetyl oxygen being in a different position, relative to the oxonium oxygen. If the acetyl oxygen is 'above' the C=O+ bond, then this causes a stabilisation due to favourable interactions between the lone pairs on the acetyl oxygen and the oxonium oxygen.

The cause of the difference between C and C', and D and D' is the torsion component. This is basically the strain caused by having the hydrogens on the carbons joining the two rings together in the less favourable trans form, rather than in the cis form which has less strain and is therefore much more stable.

However, the MM2 force-field method does not take into account the neighbouring group effect which saccharides are particularly exemplary of. In order to avoid this inadequacy, a more suitable method is MOPAC. The table below shows the MOPAC/PM6 optimised energies, which unfortunately cannot be directly compared using two different methods, although we can get a rough idea of the differences in the modelling criteria for each one. The different structures are also shown using the Jmol links.

| Monosaccharide | Energies /kJ mol-1 Jmols | |

|---|---|---|

| MM2 force-field | MOPAC/PM6 | |

| A | 61.25 | -255.55 |

| A' | 104.70 | -180.81 |

| B | 41.34 | -246.56 |

| B' | 126.60 | -227.36 |

| C | 148.29 | -255.54 |

| C' | 182.35 | -170.83 |

| D | 141.31 | -248.53 |

| D' | 194.43 | -179.74 |

The structures for MOPAC/PM6 optimised are only slightly different compared to the MM2 force-field optimised, but MOPAC/PM6 can take into account the effect of neighbouring atoms. This is most noticeable in A and B, where there is a 5-membered ring type structure, incorporating the acetyl oxygen and the sp2 carbon. In MM2 force-field, the angles on these two atoms are made to what would be generally considered ideal, at 120° rather than this open ring type. This does not take into account the stabilisation gained by invoking the neighbouring group effect. However, when you look at the structures derived by MOPAC/PM6, the open ring type structure is more defined, so clearly the MOPAC/PM6 method is superior in looking at a structure of this type.

The difference in energy between A and A' (and B and B') can be attributed to the stabilisation energy due to neighbouring group participation, as long as all other factors are considered to be approximately identical. Using the MOPAC/PM6 method, this means that the stabilisation energy of A and A' is 74.74kJ mol-1, and between B and B' is 19.2kJ mol-1.

The glycosidation reaction is well known for being highly stereospecific, C and D go singularly to the β-anomer and α-anomer respectively. These anomers are formed because the C and D intermediates are much more stable than their trans counterparts, using the MOPAC/PM6 methods, C is more stable than C' by 84.71kJ mol-1 and D is more stable than D' by 68.79kJ mol-1. This is a large difference in energy between the two conformers, and the presence of the higher energy trans form is very low, ≈0%. This allows complete progression to the β-anomer and α-anomer, without worrying about the products which may be formed from the C' and D'.

Assigning regioisomers in "Click Chemistry"

Click chemistry is a modern and emerging area of chemistry, involving 'building' a molecule from a number of small units. There are a number of advantages, although with the combination of two or more non-symmetrical molecules you need to be aware of the possible regioselectivity issues.

One such example is the catalysed cycloaddition of alkynes and azides, where both contain a substituent. This is a [3+2] cycloaddition reaction, catalysed by either a ruthenium catalyst or a copper catalysts. There are two potential products as seen in figure 12, the 1,4-triazole or the 1,5-triazole. The ruthenium catalyst produces almost exclusively the 1,5-product, whilst the copper catalyst produces predominantly the 1,4-product.

In order to confirm (or disprove!) the findings of Zhang et al[6], a selection of the molecules they synthesised and physical charaterised will be submitted to computational analysis. As a comparison, the 1,4-products will be submitted to the same computational analysis. In the interest of clarity, the same numbering scheme has been used for this study as in the original paper, (i.e., 4a here is the same 4a in the paper.) The molecule was chosen due to the low flexibility of the side chains. All NMR computations were run in CDCl3, in line with the paper to allow ease of comparison.

The molecules were first optimised using MM2 force-field and MOPAC/PM6, then submitted for further optimisation under 6-31g(d,p) (4a: D-Space; 4b: D-Space)

The Jmols are available here: 4a; 4b. They were then resubmitted for NMR simulation and the results are available below.

Regioisomers 4a and 4b

| 4a |  |

|

|

|

| 4b |  |

- |  |

4a literature: 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 29.72 (3C, s); 29.99 (1C, s); 52.60 (1C, s); 126.32 (2C, s); 127.68 (1C, s); 128.61 (2C, s); 131.26, 131.37 (1C, d); 136.37 (1C, s); 146.00 (1C, s)

4a computed: D-Space 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 27.35 (1C, s); 29.95 (1C, s); 31.57 (1C, s); 31.91 (1C, s); 54.56 (1C, s); 123.72 (2C, s); 124.38 (1C, s); 124.94 (1C, s); 125.71 (1C, s); 128.95 (1C, s); 134.28 (1C, s); 141.90 (1C, s)

4b computed: D-Space 13C-NMR (CDCl3): δ 27.95 (1C, s); 31.26 (1C, s); 31.57 (1C, s); 32.72 (1C, s); 54.59 (1C, s); 115.90 (1C, s); 124.15 (1C, s); 124.41 (1C, s); 124.58 (1C, s); 124.76 (1C, s); 125.41 (1C, s); 133.54 (1C, s); 153.89 (1C, s)

As there are relatively few non-carbon elements (and nothing really exotic present) the error can generally be assumed to be relatively small. The aromatic shifts are all slightly lower than in the literature spectrum, although this seems to be consistent throughout, the difference being approximately 2ppm. The largest difference comes from the 141.90ppm carbon, the literature counterpart is reported as having a shift of 146.00ppm. This is due to it being adjacent to a nitrogen, which is known to cause slightly errors, (supposedly 5ppm, which would totally explain this anomaly). 4a is therefore: δcorr = 148.42ppm rather than 141.90ppm. This gives a slightly higher ppm shift than in the literature spectrum. 4b is therefore: δcorr = 159.93ppm rather than 153.89ppm.

The first thing to notice is that the computed NMR does not take into account the equivalence caused by rotation around a single bond. It is clear from the spectrum reported that there is rotation around the single bond to the tertiary butyl group which results in all three methyl groups are equivalent (resulting in a peak at 29.72ppm, 3C). If the three methyl groups are averaged, then you obtain a shift of 29.57ppm, which is very close to the literature peak of 29.72ppm. This is also the case for the benzyl group, resulting in a range of peaks in the aromatic region of the spectrum, (approximately 120-135ppm). The two peaks computed for each pair of equivalent carbons can be averaged here too, resulting in a single peak of 2C, relatively close to the literature peak.

With respect to telling the two molecules apart via their 13C-NMR spectra, there are only a few differences. The aromatic benzyl ring results in similar shifts, as does the CH2 linking carbon. The tertiary butyl groups also have similar shifts for both molecule, so the difference is in the triazole ring. The carbon which is bonded to the R group has a higher ppm shift in both cases, (141.90ppm vs 128.95ppm in 4a; 153.89ppm vs 115.90ppm in 4b). The difference between the two triazole carbon shifts is larger in the 1,4-product than the 1,5-product, so this is one way to tell them apart. It is worth noting that the Zhang et al paper does not report the number of carbons responsible for each peak, besides showing the NMR spectrum and manually comparing the peak ratios, so having a static picture proved to be quite useful in working out the carbons responsible for each peak, and ensuring that they roughly averaged to correspond to the time-averaged values.

Conclusion

A range of methods have been used here to model molecules in different ways, and with differing needs for accuracy. MM2 force-field has been shown to be relatively quick and useful in terms of getting a basic optimised structure, although a little chemical intuition was required at times when a global minimum was not computationally found. In this respect it is quite limited. The MOPAC/PM6 method is a good way of modelling the molecular orbitals to identify the most likely places for nucleophilic/electrophilic attack, and much faster than trying to reason it non-computationally.

In more complex molecules, such as the monosaccharides, where there is a degree of neighbouring group effect, MM2 force-field is shown to be relatively useless, as it cannot factor in these extra criteria. MOPAC/PM6 proved to be much more adept at handling these extra things, and subsequently made it a lot easier to examine the geometry in the monosaccharides and their corresponding intermediates.

The 13C-NMR proved to be quite limited - it provides a static picture rather than a time-averaged picture. However, the shifts were predicted with quite a high level of accuracy, (once you take into account the correction factor for the nitrogen atoms), and it was very useful in assigning the peaks to the relevent carbons, from which you can roughly figure out which carbons the experimental peaks correspond to. Although it is not exactly very useful to know the exact shifts of each carbon rather than the time-averaged shifts, I found it quite interesting to see how much of an effect the lack of equivalency supposedly has on each carbon.

Overall, it can be seen that computational methods of analysis are often complimentary when used in partnership with actual chemistry. They provide a good second view at some things, although it must be noted that sometimes you do need to double check that the results make sense.

References

- ↑ Goodman, Jordan; Walsh, V.; 2001; The Story of Taxol: Nature and Politics in the Pursuit of an Anti-Cancer Drug. Cambridge University Press. p17. ISBN 052156123X

- ↑ Paquette, L., Montgomery, F., Wang, T.; J. Org. Chem.; 1995; 60; 7857

- ↑ Maier, W., Schleyer, P.; J. Am. Chem. Soc; 1981; 103; 1891

- ↑ IR Tables

- ↑ Halton, B., Boese, R. and Rzepa, H.; J. Chem. Soc. Perkins Trans. 2; 1992; 447

- ↑ Zhang et al, J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 2005; 127; 15998