Rep:Mod:01357674 ising model

Monte-Carlo Simulations

Introduction to the Ising model

Task 1: The equation for the interaction energy is shown to be . From this equation it is immediately clear that the lowest energy conformation(i.e. the most negative energy) will be the one where all the spins are oriented in the same direction (because only opposite spins result in a positive energy). If the 1D case is considered (which corresponds to a 'line' of particles), it is evident that each particle has two neighbours with whom it will interact. must always be equal to +1 in order for it to be the minimum energy, and hence by summing this over the number of neighbours the equation is simplified to . Since there are N atoms in the system, this equation is further reduced to . It can be shown that the number of dimensions of the system is proportional to the number of neighbours an atom can have. In fact n° of neighbours = 2 × Dimensions (in 2D there are 4 neighbours, in 3D there are 6 neighbours), so that the ½ at the beginning of the interaction energy expression cancels out with the 2, of the 2 × Dimensions, which corresponds to the sum of the neighbouring atoms. Hence it has been shown that

From the thermodynamics lectures last year it can be stated that entropy (S) can be expressed by the equation B, where KB is the Boltzmann constant, and W is known as the multiplicity, which is equal to the number of ways the system can adopt the particular configuration. In the case of the lowest energy configuration, there are only 2 possibilities, all spins are up or all spins are down. Hence multiplicity is equal to 2 and the entropy of the system is equal to 0.69KB.

TASK 2: By applying the formula that was previously established (E = -DNJ), it can be shown that the minimum energy of 1000 particles in 3 dimensions is -3000J. If one spin were to be flipped (i.e. 999 spins pointing one way, and 1 spin pointing the other way), the number of positive spin-spin interactions is 12. The particle has 6 neighbours with which it interacts, but furthermore, each neighbour also interacts with said particle once. From the formula it is evident that there are 6000 interactions for a system containing 1000 particles in 3D (because there are 6 neighbours which are summed for every particle), which are then halved to avoid double counting. Hence of the 6000 interactions, 12 become negative once a spin is flipped, resulting in 5688 positive interactions, and 12 negative interactions. Taking the sum of these two numbers, dividing by 2 and multiplying by J gives the interaction energy, which is equal to -2988J. As a result, the change in energy that occurs when flipping one spin in the system is equal to 12J. Since order in this system does matter, the number of ways to arrange the system so that there are 999 spins one way, and 1 spin the other way is equal to , which is equal to 2000 and is also referred to as the multiplicity. The multiplicity is multiplied by 2 because the system could be 999 up spins ans 1 down spin, or 999 down spins and 1 up spin. Hence entropy is equal to BKB. Subtracting the initial minimum entropy from this value yields the result 6.91KB, which is the entropy gained from having a more disordered system that can be arranged in more ways.

Task 3: The magnetisation of a system is defined as the overall magnetic dipole of the system, which is equal to the sum of all individual spins of the system. Hence, for the 1D case, M = +3 - 2 = +1, and similarly for the 2D case M = +13 - 12 = +1. At absolute zero, the entropy component of free energy is equal to 0 because it is dependent on temperature (A = U - TS). As a result the system will adopt the lowest energy conformation which is equal to all spins pointing in the same direction. Hence magnetisation will be equal to ±1000.

Calculating the energy and magnetisation

Task 4: The following is the initial code used for the energy and magnetisation functions:

def energy(self):

"This is the energy function of the IsingLattice class, which will take only the initialised self parameters as an input,

and will return the total interaction energy of the current lattice by using two while loops to go through each lattice point and sum the interactions."

interactions=0

i=0

j=0

while i<self.n_rows:

while j<self.n_cols:

#In this case, in order to avoid double counting only half the interactions from each lattice point are counted.

#Specifically, only the interaction with the neighbour to the right and at the bottom are added to build up the 2D grid.

#The modulus function,%, is used for the edge cases. The modulus of any number with itself returns 0, otherwise it returns the original number.

#Hence the periodic boundary conditions are observed as the last particle in a row will interact with the first particle in that same row.

interactions=interactions +self.lattice[i][j]*(self.lattice[i][(j+1)%self.n_cols]+self.lattice[(i+1)%self.n_rows][j])

j=j+1

#The column counter is reset to zero at the end so that the process can be repeated from the start of the next row.

j=0

i=i+1

#Energy in the units of J for a 2D lattice is equal to the negative of the interactions.

energy=0.0-interactions

return energy

def magnetisation(self):

"This is the magnetisation function of the IsingLattice Class, which which will take only the initialised self parameters as an input,

and will return the total magnetisation of the current lattice by using two while loops to sum all the spins."

i=0

j=0

mgt= 0

while i<self.n_rows:

while j<self.n_cols:

#These loops simply go through each lattice point in the current lattice grid and sum each individual spin (be it +1 or -1).

mgt = mgt + self.lattice[i][j]

j=j+1

#The column counter is reset to zero at the end so that the process can be repeated from the start of the next row.

j=0

i=i+1

magnetisation = 0.0+mgt

return magnetisation

Task 5:

The ILcheck.py script allows the developed code to be tested. Three scenarios are taken: one where the energy is at a minimum (i.e. all spins have the same orientation) which in this case was all positive spins, one where the entropy is at a maximum (i.e. the spins alternate in all dimensions) and as a result the energy is at a maximum, and an intermediary one between the two cases. From the picture to the right it can be seen that the code written above conforms with the expected values that are given by the ILcheck.py script, and is therefore likely to be accurate for others cases as well.

Introduction to the Monte Carlo simulation

Task 6: Each spin can be either up or down, hence there are 2 possibilities per spin. Assuming that they are distinguishable, meaning the position of each spin matters and not just the overall number of up and down spins, this would result in 2100 possible configurations for a system containing 100 particles. Dividing this by the number of configurations that can be analysed per second, 1×109 configurations, the result is the total time it would require to compute the average magnetisation or energy, which is equal to 1.27×1021 seconds. This is slightly more than 40 billion millennia, and hence a faster computational speed is imperative for these simulations to have any real world applications.

Task 7: The following is the initially implemented code for the montecarlo step function as well as the statistics function:

def montecarlostep(self, T):

"This is the montecarlostep function of the IsingLattice class, which will take the initisalised self parameters

as well as the variable temperature,T, as an input. It will then flip one spin at random in the current lattice

and calculate the energy again. If the energy is smaller than before, or if it is more probable to occur in the

Boltzmann distribution than another random number between 0 to 1, the new lattice is accepted. If not, the old lattice is kept.

The function then returns the energy and magnetisation of the lattice"

#First a copy of the original energy and magnetisation is made for later use.

energy_old = self.energy()

magnetisation_old=self.magnetisation()

#The following two lines select the coordinates of a random spin.

random_i = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_rows))

random_j = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_cols))

#This random spin is then flipped and the new lattice energy is calculated.

self.lattice[random_i][random_j]*=-1

energy_new = self.energy()

energy_diff=energy_new-energy_old

#If the new energy is lower than the previous energy the lattice is automatically accepted.

if energy_diff<0:

self.lattice=self.lattice

#In order to avoid getting stuck in a local minimum energy, some higher energy configurations are also accepted.

#A random number is selected, and if the energy is more probable in the botzmann distribution it is accepted, if not, the old lattice is taken.

else:

random_number = np.random.random()

#It is assumed that energy is already in units of K_B, and hence does not need to be divided by the constant.

if random_number<=np.e**(-energy_diff/T):

self.lattice=self.lattice

else:

self.lattice[random_i][random_j]*=-1

#The number of cycles that the montecarlostep has been run for is kept track of.

self.n_cycles=self.n_cycles+1

#The following statement take a sum of all the energies that the system has had, including the 1st energy before any montecarlo step had taken place.

if self.n_cycles ==1:

self.E=self.E + self.energy() + energy_old

self.E2=self.E2+((self.energy())**2) + (energy_old**2)

self.M=self.M + self.magnetisation() + magnetisation_old

self.M2=self.M2+((self.magnetisation())**2)+(magnetisation_old**2)

else:

self.E=self.E + self.energy()

self.E2=self.E2+(self.energy())**2

self.M=self.M + self.magnetisation()

self.M2=self.M2+(self.magnetisation())**2

return self.energy(), self.magnetisation()

def statistics(self):

"This is the statistics function of the IsingLattice class, which will take the initisalised self parameters as and input

and will return the average energy, energy squared, magnetisation and magnetisation squared"

# The montecarlo step function has already added each new energy and magnetisation to the initial energy/magnetisation class.

# The number of cycles must be n_cycles+1 because the initial energy before and montecarlo step is also included in the sum.

# A simple average is then taken and the values are returned

n_cycles=self.n_cycles+1

average_E=self.E/n_cycles

average_E2=self.E2/n_cycles

average_M=self.M/n_cycles

average_M2=self.M2/n_cycles

return average_E, average_E2, average_M, average_M2

Task 8: Below the Curie Temperature (TC), the system has very little thermal energy, and as a result the entropic driving force of the free energy expression is severely reduced (A=U-TS), whereas the internal energy component is temperature independent. As seen in the first section, flipping a spin requires thermal energy (it has an energy barrier) and hence when the temperature is below TC the system is expected to be very ordered (i.e. all spins pointing in the same direction). This means that when the system is at equilibrium the magnetisation is expected to be 0, although some spontaneous magnetisations will appear due to the montecarlo step allowing some higher energy configurations in order to avoid getting stuck in a local minimum. The image to the left shows the results of ILanim.py which plots Energy and Magnetisation per spins for each montecarlo step, which corroborate the previously explained theory. Unfortunately the ILanim.py script didn't work in the QTconsole and had to be run using Jupiter Notebook which simply returned 0.0 for all the values of the statistics function.

Accelerating the code

Task 9: Using the code ILtimetrial.py, the time it took to run 2000 steps of the montecarlo function (with the energy function as shown before) was recored. 10 trials were done, and the average value was found to be 8.50 seconds with a standard error of 0.05 seconds (the standard error is equal to the standard deviation divided by the square root of the sample size). The raw data was: 8.679668, 8.593278, 8.719527, 8.305236, 8.3494680, 8.673161, 8.459613, 8.402196, 8.508607, 8.356788 all in seconds.

Task 10: Using the sum, multiply and roll functions the code for the energy and magnetisation was simplified in order to improve efficiency.

def energy(self):

"Improoved energy function that will return the total energy of the current lattice configuration without the use of a doubble loop"

#As before only half the interactions are taken in order to avoid double counting (only those to the right and to the bottom of each lattice point).

#The np.multiply function essentially overlays two arrays of the same size and multiplies each array point of one array by the same array point in the other array.

#The np.roll function will shift the entire array 1 to the right (axis = 1), or 1 down (axis = -1), and will loop the edges around so that they go to the beginning.

#Combining these functions as shown below gives the same result as the 2 while loops did previously.

energy=0.0-(np.sum(np.multiply(self.lattice,np.roll(self.lattice,-1,axis=1)))+np.sum(np.multiply(self.lattice,np.roll(self.lattice,-1,axis=0))))

return energy

def magnetisation(self):

"Improoved magnetisation function that will return the total magnetisation of the current lattice configuration without the use of a doubble loop."

#The np.sum function takes the sum of each value within the array, and hence replaces the two while loops seen previously.

magnetisation=np.sum(self.lattice)

return magnetisation

Task 11: The code ILtimetrial.py was used again to measure the time it took to run 2000 steps of the montecarlo function (this time with the new energy and magnetisation function shown above). Once again 10 trials were done and the average was found to be 0.486 seconds, with a standard error of 0.002. The raw data was: 0.485924, 0.493978, 0.487214, 0.490701, 0.485850, 0.488033, 0.476653, 0.484385, 0.485257, 0.483946 all in seconds. It can clearly be seen that the new energy and magnetisation functions are much faster, and hence much more efficient, reducing the computing time of 2000 montecarlo steps by a factor of almost 20, which also results in the decrease of standard error by a factor of around 20.

The effect of temperature

Task 12: The graphs on the right are the result of running the code ILfinalframe.py for different lattice sizes and different temperatures. The initial lattice is chosen at random using the np.random function to fill out the spins, and thus will usually have an energy greater than the minimum energy. Running the montecarlo function means that the lattice will slowly approach the minimum energy, where it levels out. From the first set of graphs it can be seen that a larger lattice size means that more steps are necessary before the simulation reaches an average value. This is expected because the montecarlo step only flips one spin at a time, and hence having more spins means the simulation will need to run for longer before it reaches the minimum energy. For example, for a lattice size of 4x4, it takes around 100 steps, whereas the 32x32 lattice takes around 170,000 steps (it is important to note that the montecarlo step scale is not the same in all the graphs).

The second set of graphs shows that temperature has a much more subtle effect on the number of montecarlo steps it takes to reach an average value. It seems that increasing the temperature decreases the number of montecarlo steps as at a temperature of 0.1 it takes the 8x8 grid around 1100 steps to reach an average, whereas it takes the same grid only around 400 steps at a temperature of 2.0. It is interesting to note that the Curie temperature seems to be somewhere around T = 2.5, because at a temperature of 2.5 the system no longer reaches the energy minimum of all spins pointing in one direction, but rather has some spins pointing the other way as the entropic driving forces become noticeable, but not so strong as to have alternating spins. As temperature increases, the Boltzmann distribution,, will also increase, and as a result it becomes more likely for higher energy configurations to be accepted. This has two effects, first it seems that this decreases the number of steps taken to reach an average because it is easier and therefore quicker to get out of a minimum energy. Secondly, once an average is reached there are more fluctuations because the increased thermal energy means that the probability of a spin flipping spontaneously is increased.

From these graphs it was decided that for the temperature range of 0.3 to 5.0, the initial cut-off for using energies and magnetisations in average calculations were 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, 15,000, and 200,000 steps for 2x2, 4x4, 8x8, 16x16, 32x32 lattices respectively. These values are all significantly greater than the minimum cut-off steps from the graphs in order to ensure a more accurate average calculation.

From these finding, the montecarlo step function and the statistics function must now be updated to omit the initial energy and magnetisation values from their cumulative lists, until the minimum energy has been reached, at which point they can begin adding values to the list again.

def montecarlostep(self, T):

"Updated montecarlostep function that omits a specified number of energies and magnetisation from their respective lists.

As before it will take the initisalised self parameters as well as the variable temperature,T, as an input. It will then flip

one spin at random in the current lattice and calculate the energy again. If the energy is smaller than before, or if it is more

probable to occur in the Boltzmann distribution than another random number between 0 to 1, the new lattice is accepted.

If not, the old lattice is kept. The function then returns the energy and magnetisation of the lattice"

#First a copy of the original energy is made for later use.

energy_old = self.energy()

#The following two lines select the coordinates of a random spin.

random_i = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_rows))

random_j = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_cols))

#This random spin is then flipped and the new lattice energy is calculated.

self.lattice[random_i][random_j]*=-1

energy_new = self.energy()

energy_diff=energy_new-energy_old

#If the new energy is lower than the previous energy the lattice is automatically accepted.

if energy_diff<0:

self.lattice=self.lattice

#In order to avoid getting stuck in a local minimum energy, some higher energy configurations are also accepted.

#A random number is selected, and if the energy difference is more probable in the botzmann distribution it is accepted, if not, the old lattice is taken.

else:

random_number = np.random.random()

if random_number<=np.e**(-energy_diff/T):

self.lattice=self.lattice

else:

self.lattice[random_i][random_j]*=-1

#The first part of this statement from the previous montecarlostep function is completely left out, as the first energy is of no importance.

#The function only adds energies to self.E if the number of cycles is larger than a specified number, 200,000 in this case.

self.n_cycles=self.n_cycles+1

if self.n_cycles>200000:

self.E=self.E + self.energy()

self.E2=self.E2+(self.energy())**2

self.M=self.M + self.magnetisation()

self.M2=self.M2+(self.magnetisation())**2

return self.energy(), self.magnetisation()

def statistics(self):

"This is the improved statistics function of the IsingLattice class, which will take the initisalised self parameters as and input

and will return the average energy, energy squared, magnetisation and magnetisation squared"

# The montecarlo step function has already added the desired new energies and magnetisations to the initial energy/magnetisation class.

# The number of cycles must now be n_cycles minus the previous cut-off number (200,000) in order to get the correct average.

# A simple average is then taken and the values are returned

n_cycles=self.n_cycles-200000

average_E=self.E/n_cycles

average_E2=self.E2/n_cycles

average_M=self.M/n_cycles

average_M2=self.M2/n_cycles

return average_E, average_E2, average_M, average_M2, n_cycles

Task 13: In order to get a graph with error bars, the ILtemperaturerange.py code was modified. Using the 8x8 lattice as an example, the ILtemperaturerange.py file would look like this:

"This is the scipt ILtemperaturerange.py for a 8x8 lattice. It uses the class IsingLattice we have defined

to create a plot of average energy and magnetisation against temperature with error bars, and saves the raw data

in a text file"

#First of all the necessary programms are imported

from IsingLattice import *

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The system size is defined (8x8), and a lattice is made using the class IsingLattice that we created previously.

n_rows = 8

n_cols = 8

il = IsingLattice(n_rows, n_cols)

#Normally, bellow T_C half the time the lattice would go to all spins -1, whilst the other half it would go to all spins +1.

#In order to make sure all the simulations are comparable we want them to equilibrate to the same point.

#The following line makes all the spins in the lattice +1, so that the average will always go to all spins +1,

#and the equilibration time will be shorter.

il.lattice = np.ones((n_rows, n_cols))

spins = n_rows*n_cols

#The runtime determins how many montecarlo steps will be taken. To get a more accurate average, 40,000 values are taken.

#The initial cut-off for a 8x8 lattice is 5,000 steps, hence the total runtime will have to be 45,000 steps.

runtime = 45000

times = range(runtime)

#Temperature from 0.3 to 0.5 will be tested in intervals of 0.05.

temps = np.arange(0.3, 5.0, 0.05)

energies = []

magnetisations = []

energysq = []

magnetisationsq = []

#Empty error lists for energy and magnetisation are created, which will be filled in during the course of the loops.

error_e=[]

error_m=[]

for t in temps:

#For each temperature an array of energy and magnetisation is created anew.

energy_array=[]

magnetisation_array=[]

for i in times:

#This statement simply allows us to follow the progress of the conputation by printing every 100th step.

if i % 100 == 0:

print(t, i)

#The energy and magnetisation are found using the montecarlostep function from the IsingLattice class.

#The values are then added to their respective arrays.

energy, magnetisation = il.montecarlostep(t)

energy_array=energy_array+[energy]

magnetisation_array=magnetisation_array+[magnetisation]

#After each temperature run is finished the average values from the statistics function are appened to the relevant lists that will make the graph.

aveE, aveE2, aveM, aveM2, n_cycles = il.statistics()

energies.append(aveE)

energysq.append(aveE2)

magnetisations.append(aveM)

magnetisationsq.append(aveM2)

#The error is calculated by finding the standard deviation of the energies and magnetisations after the desired cut-off point.

#The standard deviation is divided by the number of spins (64) because energy and magnetisation are measured per spin.

#This error is then added to the initial error list, and the next temperature will start.

error_e=error_e+[np.std(np.array(energy_array)[5000:44999]/spins)]

error_m=error_m+[np.std(np.array(magnetisation_array)[5000:44999]/spins)]

#The IL object are reset for the next cycle

il.E = 0.0

il.E2 = 0.0

il.M = 0.0

il.M2 = 0.0

il.n_cycles = 0

#The graph is now plotted with the error bars.

fig = pl.figure()

enerax = fig.add_subplot(2,1,1)

enerax.set_ylabel("Energy per spin")

enerax.set_xlabel("Temperature")

enerax.set_ylim([-2.1, 0.1])

magax = fig.add_subplot(2,1,2)

magax.set_ylabel("Magnetisation per spin")

magax.set_xlabel("Temperature")

magax.set_ylim([-1, 1.1])

#There is no x-error as the x values are the temperatures used by the code to compute the energies and magnetisation.

enerax.errorbar(temps, np.array(energies)/spins, yerr=error_e, ecolor='black',elinewidth=1)

magax.errorbar(temps, np.array(magnetisations)/spins, yerr=error_m, ecolor='black',elinewidth=1)

pl.show()

#The data is then stacked and saved in a text file.

final_data = np.column_stack((temps, energies, energysq, magnetisations, magnetisationsq))

np.savetxt("8_newx8_new.dat", final_data)

The result of the code above is the image that can be seen to the left. As stated before, by increasing the temperature spin flipping becomes more probable, and all the spins are no longer aligned as the entropic driving force increases. When energetic driving forces are dominant, the magnetisation per spin is ±1 (always +1 in these cases as the code has defined the starting lattice as all positive spins). However, as entropic driving forces become dominant spins will tend to alternate to maximise multiplicity, and the magnetisation per spin is equal to 0 (half up and half down). It can be seen that in the temperature region between 2 and 2.8 there are strong fluctuation in magnetisation, which occur due to the fact that the critical Curie temperature is crossed, and spins go from ordered to disordered.

The effect of system size

Task 14: The ILtemperaturerange.py code from the previous task was modified to plot graphs for 2x2, 4x4, 8x8, 16x16 and 32x32 lattice sizes individually, with the same cut-off points as were discussed previously. The result can be seen on the first set of graphs, where it is evident that increasing lattice size not only decreased the error bars, but also decreases the fluctuations that occur around the Curie temperature. This could be because in a large lattice, the effect of one spin switching randomly influences the magnetisation per spin much less than for a smaller lattice.

Subsequently, all the energies and magnetisations from different lattice sizes were plotted on the same graph, however their error bars were removed because it made the graphs very cluttered and hard to interpret. It can be seen that the larger the lattice, the faster it approaches energy per spin = 0 as temperature increases, and the later it seems to go through the curie temperature (i.e. the magnetisation fluctuations start at higher temperatures). The 2x2 and the 4x4 lattices are quite far away from the others, but the 16x16 and 32x32 lattices are almost identical. This could be the result of finite size effects. Because periodic boundary conditions have been applied through the np.roll function used in the energy function of the IsingLattice class, the spin-spin interactions of the model are not actually those of a real system (where the lattice is so large it can be considered to be infinite). For example, in a 2x2 lattice each spin interacts with 2 out of the three remaining spins, which means that changing one spin alters 50% of the spin-spin interactions in that system, which should obviously not be the case in a real system. Flipping one spin in a 2x2 lattice has a much larger effect on the magnetisation per spin than flipping it in a 32x32 lattice, resulting in much larger and earlier magnetisation fluctuations.

As stated before, there seems to be very little difference between the 16x16 and 32x32 spin systems, suggesting that a lattice size of 16x16 is enough to capture long range fluctuations. The code for the bottoms two graphs is shown below:

"The following code loads the data that was previously saved in a convenient stacking, and plots the Energy per spin against temperature for different lattice sizes"

#First the necessary programs are loaded

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The previously saved data is loaded for each lattice size in a convenient stacking (each column of the array is a different quantity).

two_two=np.stack(np.loadtxt('2_newx2_new.dat'),axis=-1)

four_four=np.stack(np.loadtxt('4_newx4_new.dat'),axis=-1)

eight_eight=np.stack(np.loadtxt('8_newx8_new.dat'),axis=-1)

sixteen_sixteen=np.stack(np.loadtxt('16_newx16_new.dat'),axis=-1)

thirtytwo_thirtytwo=np.stack(np.loadtxt('32_newx32_new.dat'),axis=-1)

#The data is then plotted, and the energies are divided by the number of spins to get comparable values.

figure=pl.figure(figsize=[20,8])

pl.plot(two_two[0], two_two[1]/4,'red',label='2x2')

pl.plot(four_four[0], four_four[1]/16,'black',label='4x4')

pl.plot(eight_eight[0], eight_eight[1]/64,'green',label='8x8')

pl.plot(sixteen_sixteen[0], sixteen_sixteen[1]/256,'blue',label='16x16')

pl.plot(thirtytwo_thirtytwo[0], thirtytwo_thirtytwo[1]/1024,'yellow',label='32x32')

pl.xlabel('Temperature', fontsize=14)

pl.ylabel('Energy per Spin', fontsize=14)

pl.title('Energy of Different Lattice Sizes versus temperature',fontsize=18)

pl.legend(loc='upper left')

pl.show()

The same code can then be used to plot magnetisation per spin against temperature, only by changing the column of the array to [2] for all pl.plot() y values.

Determining the heat capacity

Task 15:

Task 16: The graph to the right shows the heat capacity vs temperature of different lattice sizes, and it is quite clear that the larger the system the more peaked it becomes around the curie temperature (in fact for an infinite lattice it should diverge). It also looks as though the peaks shift towards the left, meaning that the Curie temperature decreases with increasing system size, which must be one of the finite size effects. As stated before, in a 2x2 lattice each spin interacts with 2 of the 3 other spins, and flipping one spin would change 50% of the interactions. As a result, spin flipping has a larger energy penalty than it should have in the real system, meaning that spins prefer to stay ordered (i.e. facing the same direction) for longer. This results in a larger Curie temperature for smaller lattice sizes, as can be seen on the graph.

The following code was used to generate the graph on the right:

"The following code generates a plot of Heat Capacity vs Temperature for different lattice sizes from the raw data that was previously saved in textfiles"

#Firstly the necessary programs are imported

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The previously saved data is loaded for each lattice size in a convenient stacking (each column of the array is a different quantity).

two_two=np.stack(np.loadtxt('2_newx2_new.dat'),axis=-1)

four_four=np.stack(np.loadtxt('4_newx4_new.dat'),axis=-1)

eight_eight=np.stack(np.loadtxt('8_newx8_new.dat'),axis=-1)

sixteen_sixteen=np.stack(np.loadtxt('16_newx16_new.dat'),axis=-1)

thirtytwo_thirtytwo=np.stack(np.loadtxt('32_newx32_new.dat'),axis=-1)

#The graph is now plotted

figure=pl.figure(figsize=[20,8])

#The definition for heat capacity proved previously is used, and the energy is assumed to be in units of K_B so that the constant is neglected.

#Heat capacity is equal to the variance (mean of the energy squared minus the mean energy squared) divided by the temperature squared times the number of spins.

#The mean of the energy squared is one of the values given by the statistics function, and so is the mean. Hence heat capacity can be calculated.

pl.plot(two_two[0],((two_two[2])-(two_two[1])**2)/((two_two[0]**2)*4),'red',label='2x2')

pl.plot(four_four[0],((four_four[2])-(four_four[1])**2)/((four_four[0]**2)*16),'black',label='4x4')

pl.plot(eight_eight[0],((eight_eight[2])-(eight_eight[1])**2)/((eight_eight[0]**2)*64),'green',label='8x8')

pl.plot(sixteen_sixteen[0],((sixteen_sixteen[2])-(sixteen_sixteen[1])**2)/((sixteen_sixteen[0]**2)*256),'blue',label='16x16')

pl.plot(thirtytwo_thirtytwo[0],((thirtytwo_thirtytwo[2])-(thirtytwo_thirtytwo[1])**2)/((thirtytwo_thirtytwo[0]**2)*1024),'yellow',label='32x32')

pl.xlabel('Temperature', fontsize=14)

pl.ylabel('Heat Capacity', fontsize=14)

pl.title('Heat Capacity of Different Lattice Sizes versus temperature',fontsize=18)

pl.legend(loc='upper right')

pl.show()

Locating the Curie temperature

Task 17: Graphing the Heat Capacity vs Temperature for different lattice sizes using the C++ data showed that it was very similar to the data obtained using python. However, for larger lattices it seems to diverge more because the C++ ran for many more steps giving a more accurate average for the higher number spin systems which take longer to equilibrate. The graph on the left shows all the C++ heat capacities, while the graph on the right is a comparison between the C++ data and the python data for a 16x16 lattice. It can be seen that the divergence is largest around the peak (which is the Curie temperature), and gets smaller the further away it is from the peak. The code for this is exactly the same as for the previous section, only loading the C++ data initially instead of only the python data.

Task 18: The two graphs on either side show a fitted polynomial over the Heat Capacity vs Temperature curve of the 8x8 lattice. The graph on the left has a polynomial fit that is of the order 3, and is not very similar to the simulated curve, however the heat capacity could follow such a relationship. The graph on the right has a polynomial fit of the order 17, and whilst it adheres to the simulated curve very closely, it is quite unlikely that the heat capacity actually follows such a complex polynomial expression for temperature dependence.

The code used to create these graphs was as follows:

"The following code generates a plot of Heat Capacity vs Temperature with a fitted polynomial curve for a specific lattice size"

#Firstly the necessary programs are imported

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The previously saved data is loaded in a convenient stacking (each column of the array is a different quantity).

data = np.stack(np.loadtxt('8_newx8_new.dat'),axis=-1)

T = data[0]

#As before Heat capacity is calculated from the variance and temperature

C = (data[2]-((data[1])**2))/((data[0]**2)*64)

#A polynomial is then fitted to the data, in this case it is a 17th order polynomial

fit = np.polyfit(T, C, 17)

#A range of temperature values is then created for the polynomial, from the minimum to the maximum temperature (1000 evenly spaced points).

T_min = np.min(T)

T_max = np.max(T)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000)

#The fit object defined previously is the used to generate corresponding Heat Capacity values

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range)

#The graph is then plotted with the original line, as well as the pollyfitted curve.

figure=pl.figure(figsize=[20,8])

pl.plot(eight_eight[0],((eight_eight[2])-(eight_eight[1])**2)/((eight_eight[0]**2)*64),'green',label='8x8 original')

pl.plot(T_range,fitted_C_values,'black',label='8x8 polyfitted', linestyle='--')

pl.xlabel('Temperature', fontsize=14)

pl.ylabel('Heat Capacity', fontsize=14)

pl.title('Heat Capacity of a 8x8 Lattice',fontsize=18)

pl.legend(loc='upper right')

pl.show()

Task 19: The script from before was modified slightly in order to simply fit the polynomial around the peak. The graph to the right shows the Heat Capacity vs Temperature for an 8x8 lattice, with a fourth order polynomial peak fitted around it. The fourth order polynomial was chosen because it quite accurately describes the general trend of the peak without following every energy minimum as higher order polynomials start to do.

The new modified code was as follows:

"The following code generates a plot of Heat Capacity vs Temperature with a peak fitted polynomial curve for a specific lattice size"

#Firstly the necessary programs are imported

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The previously saved data is loaded in a convenient stacking (each column of the array is a different quantity).

data = np.stack(np.loadtxt('8_newx8_new.dat'),axis=-1)

T = data[0]

#As before Heat capacity is calculated from the variance and temperature.

C = (data[2]-((data[1])**2))/((data[0]**2)*64)

#This time, instead of using all temperatures only the temperatures around the peak will be fitted.

#The values were chosen to evenly from either side of the peak.

Tmin = 1.8

Tmax = 2.95

#Now only temperatures and the associated heat capacities between Tmin and Tmax are chosen.

selection = np.logical_and(T > Tmin, T < Tmax)

peak_T_values = T[selection]

peak_C_values = C[selection]

#A polynomial is then fitted to the data, in this case it is a 4th order polynomial

fit = np.polyfit(peak_T_values, peak_C_values, 4)

#A range of temperature values is then created for the polynomial (100 evenly spaced points between Tmin and Tmax).

peak_T_range = np.linspace(Tmin, Tmax, 1000)

#The fit object defined previously is the used to generate corresponding Heat Capacity values

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, peak_T_range)

#The graph is then plotted

figure=pl.figure(figsize=[20,8])

pl.plot(eight_eight[0],((eight_eight[2])-(eight_eight[1])**2)/((eight_eight[0]**2)*64),'pink',label='8x8 original')

pl.plot(peak_T_range,fitted_C_values,'black',label='8x8 peak polyfitted', linestyle='--')

pl.xlabel('Temperature', fontsize=14)

pl.ylabel('Heat Capacity', fontsize=14)

pl.title('Heat Capacity of a 8x8 Lattice',fontsize=18)

pl.legend(loc='upper right')

pl.show()

Task 20: A textfile containing the lattice side length as well as the corresponding Curie Temperature was created by using the following code:

"The following code creates a text file containing an array of grid sizes and their associated Curie Temperatures"

#First we choose which lattice sizes to use

lattice_sizes=[2,4,8,16,32]

data_list = []

curie_temperatures=[]

k=0

for i in lattice_sizes:

#The next line loads and appends a different lattice size textfile to data_list with each iteration of i, and stacks it in a convenient format.

data_list.append(np.stack(np.loadtxt('{0}x{0}.dat'.format(i)),axis=-1))

#As before a peak polyfit for the data is created.

T = data_list[k][0]

#Heat Capacity is calculated from the variance.

C = (data_list[k][2]-((data_list[k][1])**2))/((data_list[k][0]**2)*(i**2))

#Only temperatures around the peak are fitted

Tmin = 1.8

Tmax = 2.9

#Now only temperatures and the associated heat capacities between Tmin and Tmax are chosen.

selection = np.logical_and(T > Tmin, T < Tmax)

peak_T_values = T[selection]

peak_C_values = C[selection]

#A polynomial is then fitted to the data, in this case it is a 4th order polynomial

fit = np.polyfit(peak_T_values, peak_C_values, 3)

#A range of temperature values is then created for the polynomial (100 evenly spaced points between Tmin and Tmax).

peak_T_range = np.linspace(Tmin, Tmax, 1000)

#The fit object defined previously is the used to generate corresponding Heat Capacity values

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, peak_T_range)

#The following functions find the maximum Heat Capacity, and from that the temperature associated with said heat capacity.

Cmax = np.max(fitted_C_values)

Tmax = float(peak_T_range[fitted_C_values == Cmax])

#The curie temperature is then appended to the list

curie_temperatures=curie_temperatures+[Tmax]

#This allows us to select the temperature and heat capacity values of the next grid size.

k=k+1

#The data is now stacked in a convenient way and saved as a text file.

C_T=np.array(curie_temperatures)

L_S=np.array(lattice_sizes)

final_data=np.column_stack((L_S,C_T))

np.savetxt("Curie_Temperatures.dat",final_data)

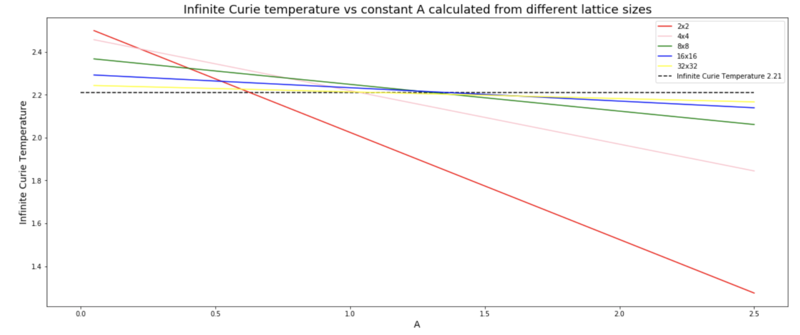

In order to find the Curie Temperature of an infinite Ising lattice, one must use the scaling factor TC,L = + TC,infinity, where L is the lattice side length, and A is an unknown constant. It is possible to find the constant at the same time as finding the infinite Curie Temperature by making a plot of the theoretical TC,infinity for a range of A values for different lattice sizes. The different lines should all cross at the same point, which is the Infinite Curie Temperature. This is exactly what can be seen on the graph to the right. The 2x2 and 4x4 lattice sizes do not cross the other lines at the same point, however it has been established that this is due to finite size effects, and that these two lattice sizes are too small to be meaningful, and can therefore be neglected. The other lines all cross roughly at the same point, which is at a temperature of 2.21. By using the Kramers–Wannier duality and making some assumption the actual value for the Curie Temperature of an infinite Ising lattice can be calculated, which is equal to 2.27 (according to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Square-lattice_Ising_model). This is less than a 3 % error from the value that we have calculated, which is surprisingly good. One would have thought that due to finite size effects (stemming from the periodic boundary conditions) the error would have been much larger. In this experiment, major sources of error were the small lattice sizes used, which save computational time but increase the dependence on single spins, as well as the sample size of the average. Although 40,000 steps is not a very small average sample size, it is by no means very accurate, and a larger number of steps should have been used to obtain more accurate results. Furthermore, using a fourth order polyfit function to model the peak curie temperatures for different lattice sizes is also a source of error as it is uncertain weather the system would actually follow such a function. If larger systems had been simulated with larger average sample sizes, perhaps one could have used the resulting function directly rather than having to rely on polyfit, which simply adds another degree of uncertainty.

The code used to obtain the previous graph was the following:

"The following code generates a plot of infinite Curie Temperatures vs A for different lattice size"

#Firstly the necessary programs are imported

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

#The previously saved data is loaded and stacked in a convenient way.

data = np.stack(np.loadtxt('Curie_Temperatures.dat'),axis=-1)

#The scaling equation to find the infinite cuire temperature is now used

k=2

infinite_curie_temperature=[]

#The first loop goes through each finite temperature

for i in data[1]:

#The second loop creates 100 points between 0.05 and 2.5 which are the values of A

for j in np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100):

#A list of infinite curie temperatures at each A point is created

infinite_curie_temperature=infinite_curie_temperature +[i-(j/k)]

#k is the lattice side length

k=k*2

#The temperature values for each lattice size are seperated

C_T_2=infinite_curie_temperature[0:100]

C_T_4=infinite_curie_temperature[100:200]

C_T_8=infinite_curie_temperature[200:300]

C_T_16=infinite_curie_temperature[300:400]

C_T_32=infinite_curie_temperature[400:500]

#The graph is plotted

figure=pl.figure(figsize=[20,8])

pl.plot(np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100),C_T_2,'red',label='2x2')

pl.plot(np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100),C_T_4,'pink',label='4x4')

pl.plot(np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100),C_T_8,'green',label='8x8')

pl.plot(np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100),C_T_16,'blue',label='16x16')

pl.plot(np.linspace(0.05,2.5,100),C_T_32,'yellow',label='32x32')

#This following line is simply a visual aid to see that the intercept is indeed around the temperature 2.21

pl.hlines(2.21,0,2.5,'black',linestyles='--',label='Infinite Curie Temperature 2.21')

pl.xlabel('A', fontsize=14)

pl.ylabel('Infinite Curie Temperature', fontsize=14)

pl.title('Infinite Curie temperature vs constant A calculated from different lattice sizes',fontsize=18)

pl.legend(loc='upper right')

pl.show()