Rep:Mod3:nathanmarch

The following is a summary of work carried out using ChemBio3D 12.0 Ultra, Gaussian 09W and GaussView 5.0.8c, Imperial College Chemistry Department - 3rd Year Computational Labs.

Conventions:

- Parentheses enclosing the final digits of a number indicate that the calculated figure has expressed digits that are beyond the accuracy of the method to ascertain i.e. an output bond length of 1.23456 Å will only be accurate to 0.01 Å and the figure will be written as 1.23(456)Å.

- 1 Hartree unit (Eh) = 2625.5 kJ mol-1 = 627.51 kcal mol-1

- Extracts from .gjf files have been edited such that they include only important information i.e. .chk directories are not shown

Module 3

The Cope Rearrangement

The Cope Rearrangement is an example of a [3,3]-sigmatropic reaction, and is unusual in one main respect: the reactant, 1,5-hexadiene, is the product. While this may cause minor problems practically when trying to model the reaction i.e. with atoms labels and so forth, what this reaction does provide is a suitably simple introduction to the field of transition state modelling; the reaction profile is symmetric, so knowledge of just one molecule is necessary to understand the path to and from the transition state.

Optimizing the Reactants and Products

"Optimizing the Reactants and Products" boils down to "Optimizing 1,5-hexadiene". 1,5-hexdiene has five carbon-carbon bonds, with free rotation possible about three. Assuming that there are six possible dihedral angles (ignoring duplication via symmetry) there are 63 possible conformations. 729 is reduced to the 10 most stable conformations, shown in Appendix 1. Which conformation eventually leads to the transition state is of vital importance in understanding the kinetics of the Cope rearrangement; if the required conformation is a high energy conformation the reaction could be stifled. Thus characterization of the conformers of 1,5-hexadiene is necessary prior to examination of the transition state.

a)

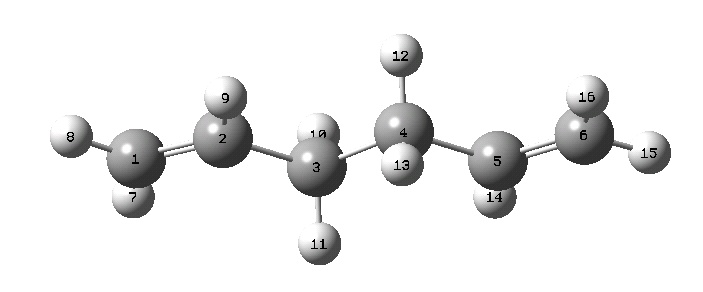

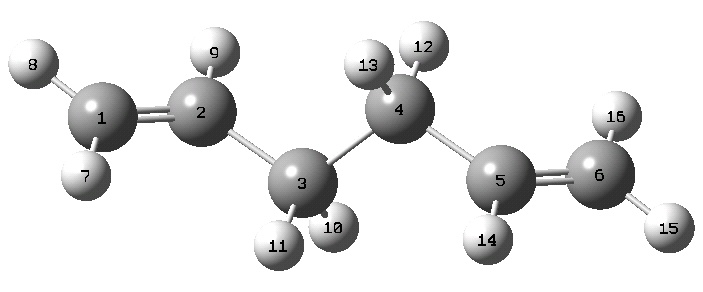

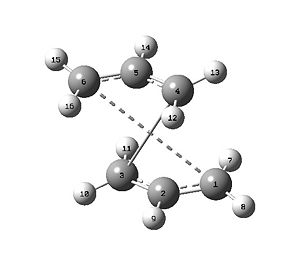

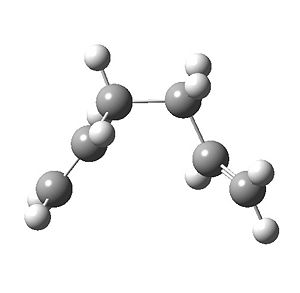

Using the ethyl and vinyl fragments in GaussView the structure of 1,5-hexadiene was input. The dihedral angles between the three carbon-carbon bond pairs was altered to be 180° to make all carbon-carbon bonds antiperiplanar. Following a cleanup by GaussView the structure emerged as follows:

This structure was then subjected to the following:

%mem=250MB # opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity hexadiene structure 1 optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_HEXADIENE_STRUCTURE1_OPT.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_hexadiene_structure1_opt_results_summary.txt

This first structure has C2{E,C2} symmetry:

b)

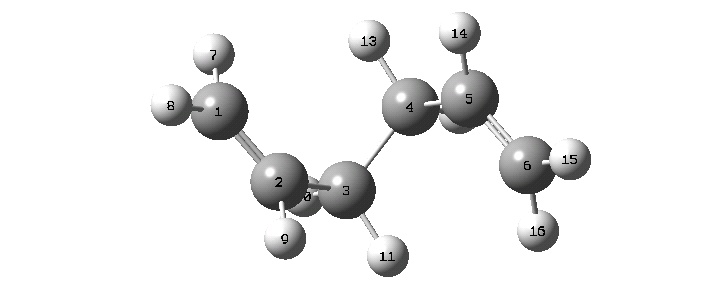

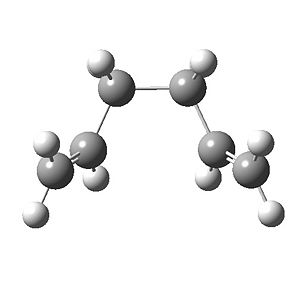

A fresh structure was drawn, with the C1-C2-C3-C4, C2-C3-C4-C5 and C3-C4-C5-C6 dihedral angles set at 60°, producing this structure:

The energies of the two starting configurations were not calculated, but if they were it would be reasonable that the 'gauche' conformation would be of higher energy than the 'anti' conformation. This would be mainly due to methylene hydrogens being synperiplanar to vinyl hydrogens in the gauche form, creating steric strain. Without the energies of the starting conformations, the energies of their optimized structures will have to suffice: in this case there is not enough information to judge whether the outcome of one optimization with one structure will be lower in energy than the optimization of another structure.

This structure was optimized:

%mem=250MB # opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity hexadiene structure 2 optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_HEXADIENE_STRUCTURE2_OPT.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_hexadiene_structure2_opt_results_summary.txt

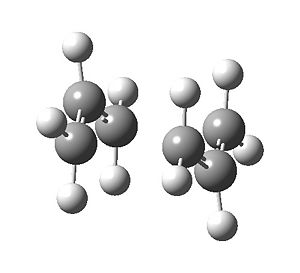

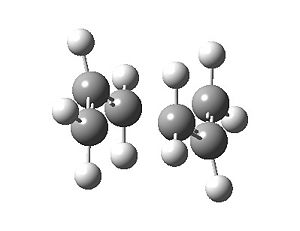

This yielded a conformer with C2 symmetry:

c)

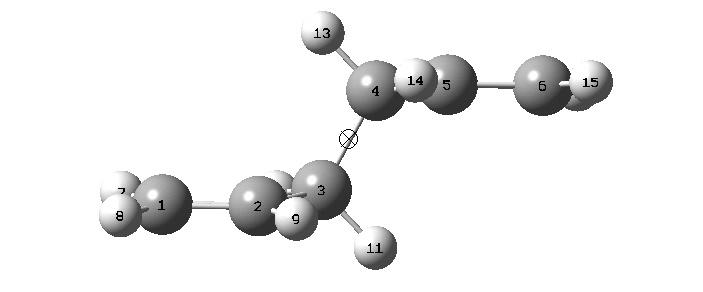

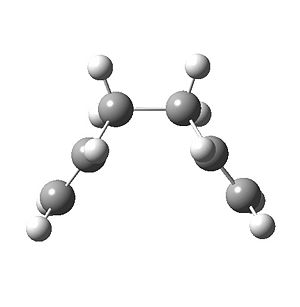

The two conformers differ in energy by about 3 kJ mol-1, with Conformer 1 being the most stable. In an attempt yo yield an even more stable structure Conformer 1 was adjusted such that the two vinyl groups were not on the same side of the C3-C4 bond, reducing their steric repulsion. To make this structure the C2-C3-C4-C5 dihedral angle was adjusted from ~60° to 180°, and then the C3-C4-C5-C6 dihedral angle was changed from 109.38823 to -109.38823 so that the vinyl groups were further apart. This produced a molecule with a centre of inversion (Ci{E,i} symmetry):

This was then optimized:

%mem=250MB # opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity hexadiene structure 3 optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_HEXADIENE_STRUCTURE3_OPT.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_hexadiene_structure3_opt_results_summary.txt

The energy of Conformer 3 is slightly higher than that of Conformer 1, rather than being lower.

d)

The conformers produced above correspond to labelled equivalents here (see Table 1).

| Table 1 - Energies and labels for conformations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conformer | Energy / Eh | Equivalent |

| 1 | -231.6926024 | anti1 |

| 2 | -231.6915303 | gauche4 |

| 3 | -231.6925353 | anti2 |

e)

The energy of Conformer 3 rounds down to that of the anti2 conformer.

f)

Once a sensible minimum has been reached at a low optimization level it is advisable to reoptimize using a better basis set; this may not alter the geometry significantly, however a proper estimate of the energy of a conformer can be essential for making good predictions about a reaction.

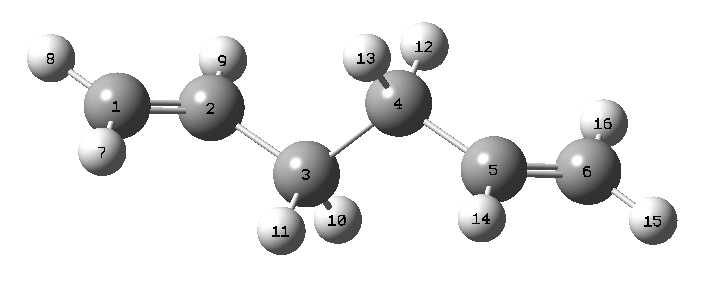

Conformer 3 was optimized via a DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d):

# opt b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity hexadiene structure 3 2nd optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_HEXADIENE_STRUCTURE3_OPT2.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_hexadiene_structure3_opt2_results_summary.txt

Overall the geometry changes very little after optimizing via the 6-31G(d) basis set, with no difference apparent when visually comparing the molecules.

| Table 2 - Structural parameters of Conformer 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Lengths | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Bond Angles | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Dihedral Angles | HF/3-21G | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) |

| C1-C2 / Å | 1.31(615) | 1.33(352) | C1-C2-C3 / ° | 124.8(15) | 125.2(86) | C1-C2-C3-C4 / ° | -114.6(84) | -118.5(88) |

| C2-C3 / Å | 1.50(886) | 1.50(421) | C2-C3-C4 / ° | 111.3(46) | 112.6(75) | C2-C3-C4-C5 / ° | -179.9(98) | 180.0(00) |

| C3-C4 / Å | 1.55(305) | 1.54(808) | C3-C4-C5 / ° | 111.3(45) | 112.6(75) | C3-C4-C5-C6 / ° | 114.6(94) | 118.5(88) |

| C4-C5 / Å | 1.50(886) | 1.50(421) | C4-C5-C6 / ° | 124.8(15) | 125.2(86) | |||

| C5-C6 / Å | 1.31(615) | 1.33(352) | ||||||

The alteration in geometry after the 6-31G(d) optimization is apparent through direct measurements made with GaussView, as shown in Table 2. Bond angles change by portions of a degree and the dihedral angles differ by a few degrees at most - it is difficult to analyse exactly why however. What can be seen is that the HF/3-21G method overestimates the strength/underestimates the length of the C=C bonds relative to the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d), and is further from the literature value (Table 3). On the other hand the predicted angles from the DFT/3-21G method are closer to the experimental values than those of the DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) method.

| Table 3 - Literature comparison of parameters of 1,5-hexadiene calculated with different basis sets | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| data for calculated values averaged from data given in Table 2 | |||||

| Parameter | Literature Value[1] | HF/3-21G | Discrepancy | DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Discrepancy |

| C=C / Å | 1.340 ± 0.003 | 1.31(615) | -0.02(385) | 1.33(352) | -0.00(648) |

| C(H2)-C(H) / Å | 1.508 ± 0.012 | 1.50(886) | 0.00(086) | 1.50(421) | -0.00(379) |

| C(H2)-C(H2) / Å | 1.538 ± 0.027 | 1.55(305) | 0.01(505) | 1.54(808) | 0.01(008) |

| C(H2)-C(H2)-C(H) / ° | 111.5 ± 0.9 | 111.3(46) | -0.1(55) | 112.6(75) | 1.1(75) |

| C(H2)-C(H)=C(H2)/ ° | 124.6 ± 1.0 | 124.8(15) | 0.2(15) | 125.2(86) | 0.6(86) |

Choosing one method over another should be informed by how closely the model yielded by the method matches reality. From the current evidence it is difficult to decide which method is preferable as both are realistic, and it is difficult to judge the relative importance of being more accurate in one prediction than in another.

g)

A frequency analysis of the 6-31G(d) optimized structure of Conformer 3 was performed:

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity hexadiene structure 3 postopt2 frequency analysis 0 1

- Log file: NM607_HEXADIENE_STRUCTURE3_OPT2_FREQ.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_hexadiene_structure3_opt2_freq_results_summary.txt

The analysis converged, yielding all-positive frequencies.

| Table 4 - Thermochemistry data from frequency analysis of 6-31G(d)-optimized 1,5-hexadiene | |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point energies / Eh | -234.469204 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal energies / Eh | -234.461857 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal enthalpies / Eh | -234.460913 |

| Sum of electronic and free energies / Eh | -234.500777 |

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

a)

An allyl fragment (CH2CHCH2) was constructed in GaussView and optimized using the HF/3-21G method:

# opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity allyl fragment optimization 0 2

- Log file: NM607_ALLYLFRAGMENT_OPT.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_allylfragment_opt_results_summary.txt

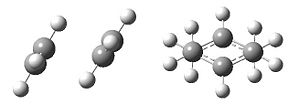

This allylic fragment was then duplicated and the two fragments were arranged to approximate the chair conformation of the transition state. The reactive carbon centre separation was set at 2.2 Å.

b)

The chair structure was then subjected to a frequency analysis and optimization to the transition state (additional keywords: opt=noeigen):

# opt=(calcfc,ts,noeigen) freq hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair frequency analysis and optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_OPTFREQ.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_optfreq_results_summary.txt

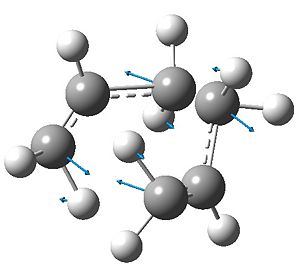

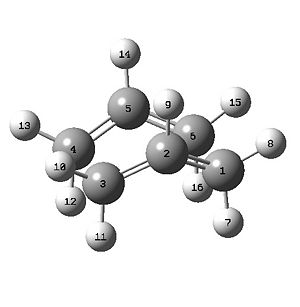

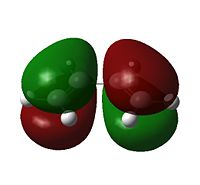

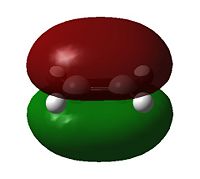

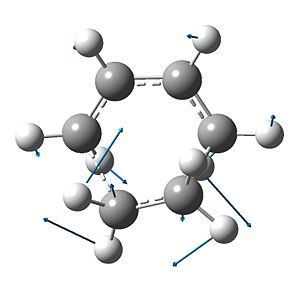

The above calculation yielded a vibration of -817(.98) cm-1 (negative: imaginary), that corresponds exactly with the bond-making/bond-breaking required by the Cope rearrangement:

A symmetric convergence of one carbon of each fragment is in antiphase to a symmetric divergence of the other pair, such that the vibration characterizes the change in bonding necessary to result in the [3,3]-sigmatropic shift.

c)

The method used in b) jumps straight from whatever estimate of the transition state has been input to the a better estimate of the transition state by ascending the potential surface. If a poor estimate is used the result may not actually represent the transition state, but might instead be a different local position on the potential surface that resembles a transition state. One way to minimise the chances of this is to do the optimization in two steps: in the first step the portions of the system that are undergoing bond-making/bond-breaking are 'frozen', and the remainder is optimized to an energy minimum; in the second step the bond-making/bond-breaking areas are 'unfrozen' and the system is optimized to the transition state. This method has advantages over that used in b) as one is more likely to find the transition state, and if for some reason the transition state is still not reached half the work has not been wasted as you have a partially optimized molecule to work with.

An optimization of the chair conformation made in a) was executed, with the reactive carbon separation frozen at 2.2 Å:

# opt=modredundant hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair optimization RCE 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_OPTRCE.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_optRCE_results_summary.txt

d)

The half-transition state produced in c) resembled the transition state produced in b), but with the reactive carbon centre separation at 2.2 Å. The next step required assigning Hessians to the bonds that were breaking or forming and optimizing the whole:

# opt=modredundant hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair optimization RCE2 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_OPTRCE2.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_optRCE2_results_summary.txt

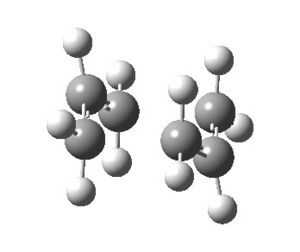

This did not produce a transition state because it was mistakenly set to optimize to a minimum. The result was the product in a non-optimal conformation:

The optimization was rerun, with the proper settings (the calculation failed without the additional keyword "opt=noeigen"):

# opt=(ts,modredundant,noeigen) hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair optimization RCE3 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_OPTRCE3.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_optRCE3_results_summary.txt

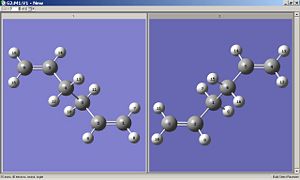

The output transition state (Fig. 7) looks identical to that produced in b), and Table 5 shows that there a no significant numerical differences.

| Table 5 - Parameter of chair transition state via Method 1 and 2 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Method 1 Determination | Method 2 Determination |

| C-C (allyl,avg.) / Å | 1.38(791) | 1.38(922) |

| C-C (trans-allyl,avg.) / Å | 2.01(992) | 2.02(072) |

| dihdral angle between tips of chair (abs(avg.)) / ° | 54.9(64) | 54.9(84) |

| angle beteen allyl tip across trans-allyl bond (avg.) / ° | 101.8(65) | 101.8(52) |

| C(H)-H (avg.) / Å | 1.07(586) | 1.07(586) |

| C(H2-H / Å | 1.07(515) | 1.07(514) |

| Energy / Eh | -231.61932229 | -231.61932239 |

Thus the method used for reaching the transition state is inconsequential, only reaching the transition state matters.

e)

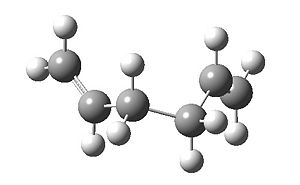

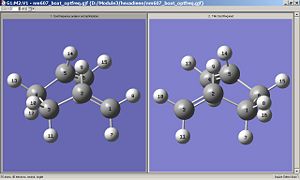

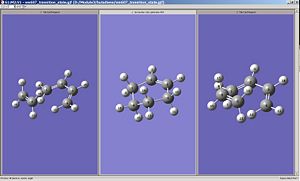

To optimize to the boat transition state the QST2 method was used. The HF/3-21G optimized anti2 structure was duplicated, maniputed and renumbered to produce the below:

This method relies on translating portions of the reactant to yield the product, and stopping at the transition state.

The code for the calculation:

# opt=(qst2,noeigen) freq hf/3-21g geom=connectivity boat frequency analysis and optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_BOAT_OPTFREQ.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_optfreq_results_summary.txt

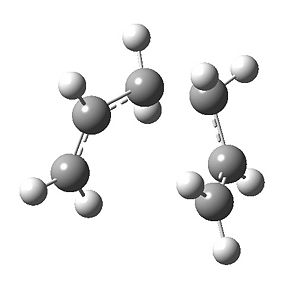

The transition state produced did not finalize (the calculation failed) - see Fig. 9. What the QST2 method did not do was rotate about any of the bonds; this would have allowed a more effective movement of the allyl fragment, and maybe the discovery of a suitable transition state. The method was not abandoned, instead the conformation of the reactant and product were altered such that the C2-C3-C4-C5 and C2-C1-C6-C5 dihedral angles, for reactant and product respectively, were 0° (originally 180°) and the C2-C3-C4 and C2-C1-C6, and C3-C4-C5 and C1-C6-C5 bond angles were 100° (originally ~110°). This yielded the structures shown in Fig. 10.

The calculation was rerun with the Fig. 10 structure:

# opt=(qst2,noeigen) freq hf/3-21g geom=connectivity boat frequency analysis and optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_BOAT_OPTFREQ2.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_optfreq2_results_summary.txt

The first time this calculation was run it failed and produced an unsymmetric, non-optimal transition state. The input structure was then symmetritized and the calculation repeated to produce the files given above.

f)

The chair transition state best resembles the gauche3 conformer, while the boat transition state best resembles the gauche2 conformer. This is not, however, a sure sign of the conformer that would result from the completed reaction in either case. An Intricsic Reaction Coordinate calculation will find the geometric minimum starting from the transition state. Such a calculation was executed on the chair transition state, with a 50 step limit:

# irc=(forward,maxpoints=50,calcfc) hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair IRC50 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_IRC50.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_IRC50_results_summary.txt

The structure produced was not one on the list of stable conformers, despite completing in only 26 steps. This can be rectified by calculating the force constants along with the IRC:

# irc=(forward,maxpoints=50,calcall) hf/3-21g geom=connectivity chair IRC50 with force constants 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CHAIR_IRC50FORCECONSTANTS.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_IRCForceConstants_results_summary.txt

Calculating the force constants resulted in a total of 47 steps, with the final product corresponding to the gauche2 conformer (having the correct energy also).

This same process was also done for the boat transition state but with a maximum of 60 steps given how close the chair optimization came to its maximum:

# irc=(forward,maxpoints=60,calcall) hf/3-21g geom=connectivity boat IRC50 with force constants 0 1

- Log file: NM607_BOAT_IRC50FORCECONSTANTS.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_IRCForceConstants_results_summary.txt

As it happens, both transition states output the conformers predicted, with the boat transition state yielding a structure closest to the gauche3 conformer(see Fig. 14). While it is close, it is not exact, therefore an HF/3-21G geometry optimization was executed:

# opt hf/3-21g geom=connectivity boat IRC50 with force constants optimization 0 1

- Log file: NM607_BOAT_IRC50FORCECONSTANTS_OPT.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_IRCForceConstants_opt_results_summary.txt

This did not yield the gauche3 conformer, but it seems that a novel conformer (Cs{E,σh}) has been identified, of noticably high energy (-231.68302525 Eh) but stable nonetheless. A check of the point group of the input configuration showed that the molecule had no enforced symmetry, so this conformer is valid.

g)

The activation energy for the Cope rearrangement can be determined by comparing the energies of the reactant with that the of the transition state. To achieve this it is best to use energies derived from high-level optimations; thus the chair and boat transition states were reoptimized (DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d)):

The code for reoptimization of the chair transition state:

# opt=(ts,noeigen,modredundant) b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity chair optimization 6-31G(d) 0 1

- D-space reference: [1]

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_opt6-31G%28d%29_results_summary.txt

The code for reoptimization of the boat transition state:

# opt=(ts,modredundant,noeigen) b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity boat optimization 6-31G 0 1

- D-space reference: [2]

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_opt6-31G%28d%29_results_summary.txt

The 6-31G(d) optimization of the chair transition state did not converge, but was not repeated due to the long calculation period (>50 min); the energy value was in-range.

To determine the thermochemical data a frequency analysis of each structure was necessary:

The code for the frequency analysis of the chair transition state:

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity chair postopt6-31G(d) frequency analysis 0 1

- D-space reference: [3]

- Results summary: Nm607_chair_opt6-31G%28d%29_freq_results_summary.txt

The code for the frequency analysis of the boat transition state:

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity boat postopt6-31G frequency analysis 0 1

- D-space reference: [4]

- Results summary: Nm607_boat_opt6-31G%28d%29_freq_results_summary.txt

| Table 6 - Energies of transition states and reactant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Chair Transition State | Boat Transition State | Reactant (anti2) |

| Electronic Energy / Eh | -234.55493653 | -234.54309292 | -234.61171035 |

| Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies / Eh | -234.414005 | -234.402336 | -234.469204 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies / Eh | -234.407802 | -234.396003 | -234.461857 |

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies / Eh | -234.406858 | -234.395059 | -234.460913 |

| Sum of Electronic and Free Energies / Eh | -234.443209 | -234.431744 | -234.500777 |

| Relative Energy (from Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies) / kJ mol-1 | 141.92 | 172.90 | 0.00 |

| Relative Energy (from Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies) / kcal mol-1 | 33.92 | 41.32 | 0.00 |

The relative stability of the reactant and the boat transition state is a little higher than that given, but that for the chair transition state is corrent to 2 d.p.. The discrepancy for the boat transition state is likely what lead to the novel product conformation; what precisely caused either is however unclear.

From the above data it is clear that the Cope rearrangement is markedly more favoured if proceding via the chair transition state; obviously this is a result of the minimisation in steric strain in the transition state.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

Diels Alder cycloadditions are commonly held to be concerted processes, where the formation of two σ-bonds between the termini of a diene and a dienophile happens symultaneously. A transition-state analysis should verify the truth of this. Another issue that can be understood via transition-state analysis is the selectivity of Diels Alder reactions towards the so-called 'endo' or 'exo' products - it is worth noting that an analysis of the kinetic of such a reaction was completed here.

The first reaction that will studied could be considered the simplest Diels Alder reaction: butadiene + ethene.

i)

Cis-butadiene was built in GaussView and optimized via the semi-empirical AM1 method:

# opt am1 geom=connectivity cis-butadiene optimization AM1 0 1

- Log file: NM607_CIS-BUTADIENE.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_cis-butadiene_opt_results_summary.txt

The optimized cos-butadiene had a C=C bond length of 1.33(499) Å, a C-C bond length of 1.44(946) Å and a C-C-C bond angle of 125.6(62).

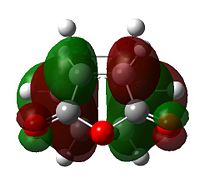

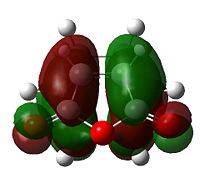

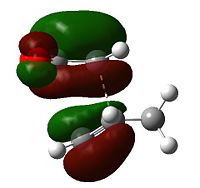

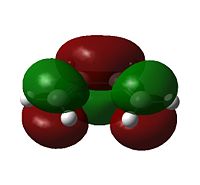

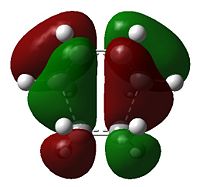

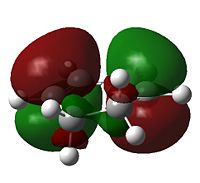

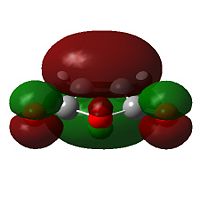

Examining the orbitals can provide information about the feasibility of a reaction; in the case of Diels Alder chemistry one expects the HOMO of the diene/dienophile interacting with the LUMO of the dienophile/diene to have the same symmetry. The plane of importance is the σv plane; orbitals can be classed as either symmetric or antisymmetric with respect to this plane, and only orbitals with the same symmetry will interact during bonding. Thus the symmetries of the HOMOs and LUMOs of cis-butadiene and ethene are shown below. 'a' indicates that the orbital in question is antisymmetric with respect to the σv, while 's' indicates that the orbital is symmetric with respect to the same plane.

| Table 7 - HOMOs and LUMOs of cis-butadiene and ethene | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cis-butadiene | ethene | ||

| Orbital | Symmetry | Orbital[3] | Symmetry[4] |

|

a |  |

s |

|

s |  |

a |

Thus the HOMOs cannot interact with one another, nor the LUMOs together, but interaction between either HOMO/LUMO pair is perfectly possible.

ii)

To determine the transition state for the cis-butadiene/ethene reaction the QST3 method was used: the three structures necessary, cis-butadiene + ethene, the transition state and cyclohexene, were built using GaussView or built in ChemBio3D and exported into GaussView. Next, the three structures were arranged to allow a QST3 calculation; the reactants were arranged to imply an angled trajectory (favoured by sterics); the transition state required only that the ethene be positioned close to the cis-butadiene (above the plane) and the product was left unaltered (in the conformation produced by ChemBio3D).

The code for QST3 optimization:

# opt=(calcall,qst3,noeigen) freq am1 geom=connectivity Title Card Required 0 1

- Log file: NM607_TRANSITION_STATE.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_be_transition_state_results_summary.txt

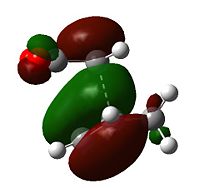

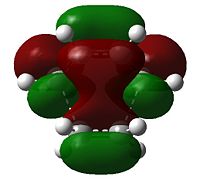

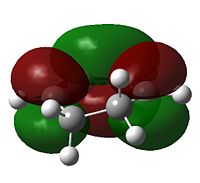

It is the LUMO of ethene that interacts with HOMO of cis-butadiene to yield the HOMO of the transition state, and it is the the HOMO of ethene interacts with the LUMO of cis-butadiene to produce the LUMO of the transition state. The reaction is a thermal π4s + π2s cycloaddition, it is a suprafacial addition of a four-electron π-system to a two-electron π-system; the reaction proceeds via a Hückel transition state, and is symmetry permitted.

| Table 8 - Molecular orbitals of the cis-butadiene/ethene transition state | |

|---|---|

| Orbital | Symmetry |

|

a |

|

s |

As would be expected the C(H2)-C(H) bond lengths are longer than their equivalents in cis-butadiene, being 1.38(186) Å (avg.) and the C2-C3 bond demonstrates the imminent increase in bond order, being a more C=C-reminiscent 1.39(748) Å (literature value for typical C=C bond: 1.34 Å[5]). The C1-C6 and C4-C5 bond lengths are 2.11(926) Å and 2.11(927) Å respectively, and thus the transition state can be considered symmetrical - both bonds form symultaneously. The Van der Waals radius of carbon is 1.70 Å[6]; the partially formed σ-bonds are less than double the Van der Waals radius.

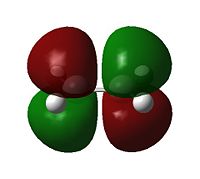

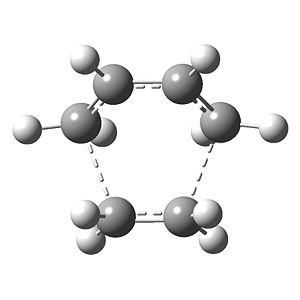

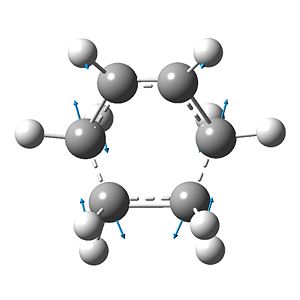

pictured with manual displacement at -1.0 and default vector magnitude

pictured with manual displacement at -1.0 and increased vector magnitude

The bond vibration for the partial σ-bonds, that is evidence of a sound transition state, has a frequency of -956(.21) cm-1. The vibration shows the symmetric, concerted formation of the two new σ-bonds. The lowest positive-energy vibration (147(.24) cm-1) is, however, asymmetric and includes a torsional component about the ethene portion - this is indicative of the final structure that the product will adopt (Fig. 19).

This could indicate that in certain cases, where steric strain deters one end of the ethene approaching, there could be a delay in the formation of one σ-bond and asynchronous bond formation.

iii)

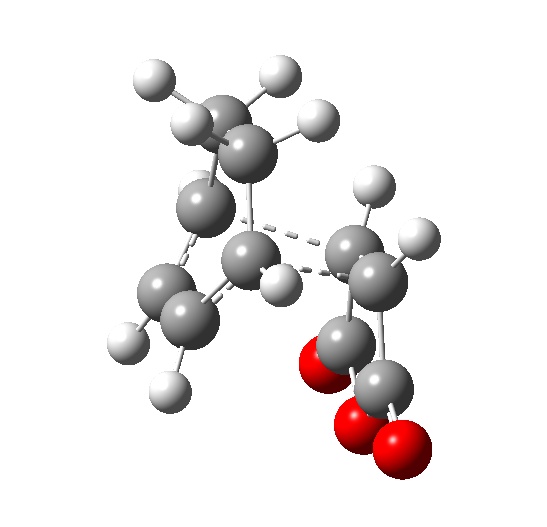

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene reacts with maleic anhydride according to the same Diels Alder chemistry as seen with cis-butadiene and ethene. What is different about this new system is that the complexity of the reacting groups allows two different products: the endo and the exo product. The approach path for each isomer is different, and would be difficult to enforce using QST2. Thus the method of choice is QST3, which allows direct control over the proposed transition state.

The reactants and products were built in ChemBio3D, and imported into GaussView. Each was optimized via the AM1 semi-empirical method and used where necessary to construct the transition states. The QST3 method was used on both transition states, but it was significantly more problematic finding the transition state for the endo conformer: repeated QST3 cycles (substituting the output transition state as the guess in the next calculation) did not yield a suitable transition state; nor did optimizing using the freeze/optimize-to-minimum/un-freeze/optimize-to-transition-state process work. What was eventually done was a careful manual adjustment of the transition state to a sensible shape - adjustment of the bond lengths such that all C-C bonds undergoing a change in bond order were set at 1.44 Å (bond order ~1.5) save for the inter-fragment bonds which were set at 2.2 Å, and geometric rearragements such as adjusting the groups around the methynes such that they were equidistant.

The code for the final endo transition state optimization:

# opt=(calcall,ts,noeigen) am1 geom=connectivity endo transition state opt2 AM1 0 1

- Log file: NM607_ENDO_TRANSITION_STATE_OPT3.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_endo_transition_state_opt3_results_summary.txt

The exo transition state was determined directly from a sensibly laid-out guess at a transition state in a QST3 calculation:

# opt=(calcall,qst3,noeigen) freq am1 geom=connectivity Title Card Required 0 1

- Log file: NM607_EXO_TRANSITION_STATE.LOG

- Results summary: Nm607_exo_transition_state_results_summary.txt

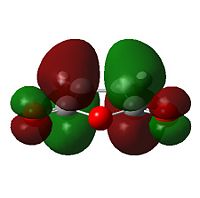

The vibrations of each transition state were of the right character to suggest that the transitionstate had in fact been reached and both calculations converged. The endo transition state had a calculated imaginary frequency of -806(.39) cm-1:

Likewise the exo transition state had an imaginary vibration that displayed symultaneous formation of both σ-bonds:

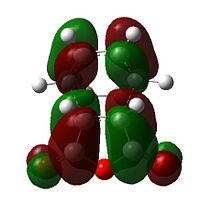

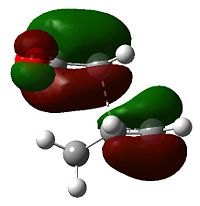

Diels Alder chemistry is sensitive to molecular orbital overlap, prior to bonding so analysing the molecular orbitals of the trasition states is vital for an understanding of the reaction kinetics. To properly analyse the molecular orbitals of the transition states it is first necessary to examine the molecular orbitals of the reactants:

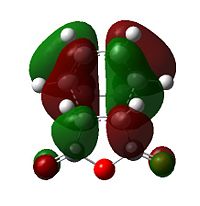

| Table 9 - HOMOs and LUMOs of cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| cyclo-1,3-diene | maleic anhydride | ||

| Orbital | Symmetry | Orbital | Symmetry |

|

a[7] |  |

s |

|

s |  |

a |

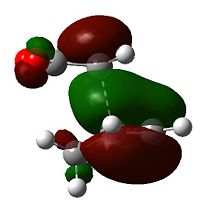

The anhydride group is a strong electron-withdrawing group, and favours donation into the LUMO of maleic anhydride over donation from the HOMO. Thus, the interaction between the LUMO of maleic anhydride and the HOMO of cyclohexadiene is strongest; it is these two orbitals that combine to form the HOMO of the transition state.

The nodal character of the HOMO of the endo is such that all the oxygen atoms in the anhydride functionality have nodes in their centres (and lobes above and below, similar to p-orbitals). The lobes of the central oxygen atom extend outward, toward the other two oxygen atoms, rather than upwards/downwards as the other oxygen atoms' lobes do. The same situation exists for the endo transition state but the blending between the lobes of the central oxygen and any others is visible at lower isovalues than for the endo transition state.

Looking at the energies of the two isomers one is lead to the conclusion that the endo product is the kinetic product (the endo transition state is 2.85 kJ mol-1 more stable), but the question is "why?": first of all there is the secondary orbital overlap effect:

What is demonstrated in Fig. 23 is that the endo transition state is stabilized, relative to the exo transition state, through additional electron donation from the π-system of cyclohexa-1,3-diene into the orbitals of the electron-poor maleic anhydride. There is no extra bonding involved, so the stabilization is small, but the stabilization is sufficient to favour the endo over the exo product in a kinetically controlled reaction. In such reactions it is also often a case that steric considerations impact on the preferred product (kinetic or otherwise). In this case the exo transition state is destabilized more than the endo transition state due to repulsion between the anhydride group and the cyclohexadiene ring.

These two effects are of similar magnitude, and can often balance one another to the point where careful analysis is required to determine which product is the kinetic product and which is the thermodynamic product[8]. In this case they act in the same direction, to stabilize the endo transition state, and stabilize the endo product (AM1 optimizations of both products yielded a 0.69 kJ mol-1 gap between the two, favouring the endo product: [log file]; [[https://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/images/7/7f/Nm607_exo_opt_results_summary.txt%7Cexo log file). This is what the raw data indicates but it would be foolish to assume that the results are entirely accurate given the closeness in energy between the isomers and their transition states; it is entirely possible that a more intensive analysis could reverse the relative energies. However, the endo transition state can be rationalized as being the more stable and therefore the conclusion is that the endo product is at the very least the kinetic product.

References

- ↑ G. Schultz, I. Hargitta, J. Mol. Struc., 1995, 346, 63-69. DOI:10.1016/0022-2860(94)09007-C

- ↑ Note bent-back hydrogens

- ↑ Calculated using same method as for cis-butadiene.

- ↑ As if ethene were in the same plane as cis-butadiene, subject to the same symmetry element.

- ↑ J. C. Kotz, P. Treichel, Chemistry & Chemical Reactivity, Volume 2, 2008, 7th Edition, 387. ISBN 978-0-495-38713-8

- ↑ R. C. Smoot, R. G. Smith, J. Price, Merrill Chemistry, 1999, 316. ISBN 978-0-028-25527-9

- ↑ Not technically, but the approximation is sufficient for the purpose of showing compatable orbitals

- ↑ M. A. Fox, R. Cardona, N. J. Kiwiet, J. Org. Chem., 1987, 52, 1469–1474. DOI:10.1021/jo00384a016