Rep:Mod3:ch1508

Module 3:Physical Computational Chemistry Lab

Ciarán Healy March 2011

The Cope Rearrangement

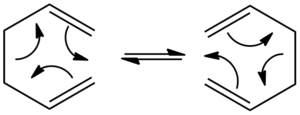

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3] sigmatropic reaction where one (σ) bond is broken and another, similar, bond is formed from a π system. Here we are investigating the Cope Rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene. This reaction is known to take place via a concerted pericyclic transition state.

Here we will attempt to find the energy minima and maxima (transition states) for this process. To achieve this, Gaussian will be used, with the Hartree-Fock (HF) and density functional theory (DFT) methods.

Optimising the Various 1,5-Hexadiene Conformers

A molecule of 1,5-hexadiene was sketched, and modified to find a series of local energy minima. This gave ten different conformations, which can be seen, along with their energies in the table below. These initial optimisations were carried out using a relatively non-intensive HF method.

| Conformer | Structure | Point Group | Energy/Hartrees HF/3-21G |

| Gauche 1 |

|

C2 | -231.68771 |

| Gauche 2 |

|

C2 | -231.69167 |

| Gauche 3 |

|

C1 | -231.69266 |

| Gauche 4 |

|

C2 | -231.69153 |

| Gauche 5 |

|

C1 | -231.68962 |

| Gauche 6 |

|

C1 | -231.68916 |

| Anti 1 |

|

C2 | -231.69260 |

| Anti 2 |

|

Ci | -231.69254 |

| Anti 3 |

|

C2h | -231.68907 |

| Anti 4 |

|

C1 | -231.69097 |

It can be seen from the table that most stable form of the molecule is the gauche 3 form, rather than any of the anti forms. This is not what you might expect based on kinetic considerations. The most likely explanation for the extra stabilisation of the gauche form is probably related to the MO situation within the two molecules. To that end, the MOs for the anti 1 and gauche 3 forms can be seen here:

The most obvious difference that can be seen from these MO plots is the constructive overlap between the two π bonding orbitals of the C=C bonds in the gauche form. This should provide significant extra stabilisation for this form. One can also see some overlap between one one such π orbital and an adjacent σ*[1].

The anti 2 form was futher optimised using a DFT method, with a 6-31* basis set. This allowed us to compare the two methods by looking at the data generated.

| Method Used | Structure | Dihedral angle (C1 to C4) | Energy (Atomic Units)] | Energy (KJmol-1) |

| HF/3-21G |

|

114.7 o | -231.692535 | -6.08 x 105 |

| DFT/B3LYP/6-31G* |

|

118.6 o | -234.61171 | -6.16 x 105 |

The data indicates that the DFT optimisation is the more accurate, since it has the lower energy, suggesting a more stable conformation. This is reinforced by the geometry of the molecule, for example by comparing the bond lengths to literature values[2].

| HF/3-21G | DFT/B3LYP/6-31G(d) | Literature[3] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C=C | 1.316 | 1.334 | 1.340 |

| C-C Type A | 1.509 | 1.504 | 1.508 |

| C-C Type B | 1.553 | 1.548 | 1.538 |

This shows that the bond length values for the DFT approach are closer to literature, and so can be deemed to be more accurate.

Frequency Analysis of 1,5-Hexadiene Conformers

This sort of analysis is useful in determining whether a minimisation has been completed properly. If any negative frequencies are detected, then a minimum has not been found. If one such imaginary frequency is present, then a transition state has been found.

The following analysis was carried out using the more accurate DFT result, a frequency calculation was run which produced the following low frequencies (in cm-1).

Low frequencies --- -9.4912 -0.0012 -0.0010 -0.0009 3.7270 12.9902 Low frequencies --- 74.2834 80.9977 121.4157

Although some of these frequencies are slightly negative, this can be put down to numerical problems with the precision of the calculation. The fact that these are within 10cm-1 of zero reinforces this impression.

Additional data can be found in the "thermochemistry" section of the .log file. This includes:

- Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies – this is the potential energy at 0 K including the zero-point vibrational energy: E = Eelec + ZPE

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies – this is the energy at 298.15 K and 1 atm. Includes contributions from the translational, rotational and vibrational energy modes occurring at this temperature: E = E + Evib + Erot + Etrans

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies – contains an extra correction for RT which is important when analysing dissociation reactions such as this one: H = E + RT

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies – this incorporates the entropic contribution to the free energy: G = H - TS

The following data was recorded from the file for Anti 2 (values in a.u., T = 298.15K):

- Sum of Electronic and Zero-point Energies = -234.46920

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies = -234.46186

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Enthalpies = -234.46091

- Sum of Electronic and Thermal Free Energies = -234.50078

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

There are two available structures for the transition state for the Cope rearrangement, boat and chair, in calculating these structures, we can compare different procedures for looking at transition states, at the same time as we investigate the rearrangement.

Optimising the Chair

An drawn using gaussview and optimised with a HF/3-21G method was used as the foundation of the initial attempts to produce a transition state. Two of these were put together and aligned so as to give the basis of a chair shape. The distances between the atoms where C-C bonds were expected to form were set to 2.20Å. This gave the following guess structure: .

Using this structure, a simple Gaussian calculation was set up, optimising to a TS(Berny) using the HF/3-21G method. The additional keyword opt=noeigen was used to prevent the calculation crashing. This gave this . An alternative method for optimisation is known as the frozen coordinates method. Gaussview's redundant coordinate editor is used to freeze the coordinates of the terminal carbon atoms, with the bonding distance initially being set at 2.20Å. This molecule underwent a TS minimisation. The structure resulting from this was opened, and the redundant coordinate editor was accessed. This was used to create a similar set up as before for the terminal carbon atoms, with the difference that this time the bonds were not frozen, but set to derivative. This structure resulted from the method, and this from the method.

A frequency analysis was carried out on the various results, the results of this, and some other data can be found in the table below:

| Simple TS (Berny) Method | Frozen Bonds Method | Derivative Method | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (a. u.) | 231.61932 | 231.61519 | 231.61932 | |||||||||

| Terminal C-C distance (Å) | 2.020 | 2.200(fixed) | 2.020 | |||||||||

| Imaginary Frequency (cm-1) | -817.9 | -765.1 | -818.0 | |||||||||

| Animation |

|

|

|

The fact that the final results of the simple TS(Berny) and frozen/derivative bonds methods are essentially the same (both end up with the same energy to five decimal places, the same bond length to three decimal places, and very similar imaginary vibrations) suggests that the frozen coordinates approach is probably an unnecessary complication for such a simple system as this one. However for systems where the likely structure of the transition is not known, the frozen coordinates/derivative method may well prove useful in accurately establishing the structure.

As can be seen by looking at the animations of the asymmetric imaginary vibrations, these negative frequencies correspond to the concerted bond breaking/forming process that is the Cope rearrangement. This is something we can expect to see regularly, with imaginary frequencies for transition states being linked to whatever transformation is taking place. This can help us to be sure of the mechanism for a process. Here it strongly suggests that the Cope rearrangement is a concerted process (which we would expect given its pericyclic nature).

Incidentally, the reason we associate negative, or imaginary, frequencies with transition states is that the frequency is based on the second derivative of the potential energy surface. Transition states are found at maxima, where the second dervivative of the potential energy surface will be negative (at minima this will be positive, so we will only see positive frequencies).

Optimising the Boat

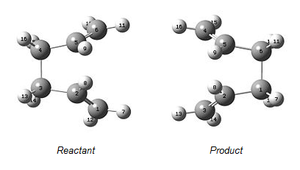

In order to investigate another technique, the optimisation for the boat form TS would be carried out using QST2. In this method, the structure of the reactant and product are specified, and the reaction pathway between the two points is calculated. The point on this pathway which is the highest in energy is the transition state.

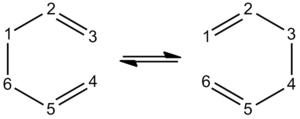

To carry out this method, it is extremely important that the reactant and product are appropriately labelled, this is especially true in this case, where the reactant and product have the same form (anti 2 type 1,5-hexadiene), but atoms are moved around. This can be seen in the image below.

Once this numbering had been carried out (using the DFT optimised anti 2 type 1,5-hexadiene from earlier), the next stage of the process - the calculation - could be undertaken. The programme was set to optimise the geometry and calculate frequencies.

The initial calculation gave an unsatisfactory result. The was similar in some ways to the chair form, it is different in so far as it is more dissociated.

In an attempt to produce the desired boat transition state, the reactants and products need to be modified. This modification involves rotation around the central bond, starting from anti 2 to give the form shown.

The QST2 calculations performed using these as a starting point, gave a better result. This is clearly a boat form, and frequency analysis shows that this a transition state (one negative frequency at ). The energy was recorded as -231.60280 with a bonding distance of 2.140Å.

This process appears to be concerted, with one bond forming as the other breaks. This, along with the similar result from the previous section backs up the fact that this is a concerted, pericyclic process.

Activation Energies

We can compare the two different transition states (chair and boat) in terms of energy and activation energy. At the same time we can also compare the results produced by the different methods (HF and DFT) - values for 0K supplied in the appendix of the lab instructions are included for reference.

The results for the HF method:

| Structure | Energy (kcalmol-1 at 298.15K) | Activation Energy (kcalmol-1at 298.15K) | Energy (kcalmol-1 at 0K) | Activation Energy (kcalmol-1at 0K) | Experimental Value (kcalmol-1 at 0K)[4] |

| Chair | -1.45341 x 105 | 44.70 | -1.45246 x 105 | 45.70 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | -1.45331 x 105 | 54.74 | -1.45236 x 105 | 55.60 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

The results for the DFT method:

| Structure | Energy (kcalmol-1 at 298.15K) | Activation Energy (kcalmol-1at 298.15K) | Energy (kcalmol-1 at 0K) | Activation Energy (kcalmol-1at 0K) | Experimental Value (kcalmol-1 at 0K)[4] |

| Chair | -1.47185 x 105 | 34.34 | -1.47096 x 105 | 34.06 | 33.5 ± 0.5 |

| Boat | -1.47176 x 105 | 43.06 | -1.47088 x 105 | 41.96 | 44.7 ± 2.0 |

These DFT activation energies are in good agreement with the literature. It is hard to be completely certain about this accuracy (due to the difference in temperature), but we would expect these values to be relatively similar to those at higher temperatures. These values show that the DFT method is appropriate in its complexity to give good results for this relatively simple system.

The HF system, on the other hand, gives values some way away from the experimental activation energies. This shows us that this method is not suitable for calculating the energies themselves, although its speed does mean that it has a useful roll to play in finding the initial geometries, before more complex optimisations are carried out.

As we can see, the DFT model predicts a more stabilised, lower energy system than does its, less accurate, HF counterpart. This is in line with what we might expect.

In both cases the relative activation energies show that the chair transition state is the kinetically favoured process. This is most likely due to steric repulsions in the boat transition state.

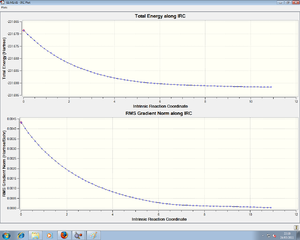

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Method

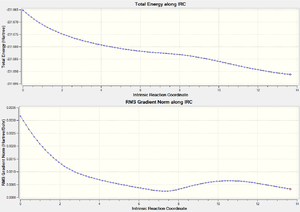

It is difficult, if not virtually impossible, to identify what conformers of 1,5-hexadiene have given rise to the transition states calculated by means of simple optimisations. One method which enables us to see what the starting form of the molecule is is the intrinsic reaction (IRC) method. This works by following the reaction energy pathway down from the maximum of the transition state to the minima that represent products and reactants (in this case, the reactants are essentially the same as the products; so the reaction profile is expected to be symmetrical, and the calculation need only run one way).

The chair state was the first to be tackled. Initially, a relatively low level IRC was used (HF method). This was set to 50 steps, only calculating the force constants at the start of the process. This gave this , which was further optimised using a more rigourous IRC model, with 100 steps, calculating the force constant every step. This takes longer, but gives an extremely accurate . This was further optimised using the DFT method, to give an energy of -234.61071a.u.. The structure is that of the gauche 2 conformer.

Here we see the lines flattening, the RMS gradient decrease as a minimum is approached.

A similar process was carried out for the boat system. With the initial process, a strange result was achieved, but more accurate IRCs (similar to that described above) starting from two different points on the curve converged to the same point. For the sake of brevity and simplicity, only one of the plots is shown. The taken forward resulted in the following . The energy was recorded as -231.69119a.u. following a DFT optimisation. The structure matches that reported for the gauche 3 conformer.

These are the relevant plots for the boat transition state IRC.

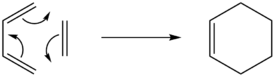

Diels Alder Cycloaddition

This section will focus on using the sorts of techniques utilised above to study the transition states seen in the [4s + 2s] cycloadditions know as Diels-Alder processes. These well-studied reactions see a conjugated diene reacting with a dieneophile. Much like the in Cope rearrangement, the transition states for these reactions are concerted pericyclic processes. The reaction can be allowed or forbidden based on symmetry considerations. Put simply, the HOMO of one of the molecules must be able to overlap with the LUMO of the other. For this to had they must be of the same symmetry (i.e. symmetric or antisymmetric).

Prototype Diels Alder: Cis-Butadiene and Ethylene

We are investigating a protype form of the Diels-Alder class of reactions utilising simple molecules. The reaction between cis-butadiene and ethylene can be seen below.

Optimising the reactants

In order to get an accurate transition state, we need accurate structures for the reactants. As discussed above, the MOs and their symmetry are very important for processes like this. To this end, the HOMO and LUMO for the two compounds can be seen below.

| 1,3-Butadiene | Ethylene | |||

| HOMO | LUMO | HOMO | LUMO | |

| MO |

|

|||

| Symmetry | Antisymmetric | Symmetric | Symmetric | Antisymmetric |

As can be seen, orbital symmetry suggests that there is potential for overlap between the HOMO of either molecule the LUMO of the other. This means that a reaction is possible here.

Optimizing the Transition State

The initial guess for the transition state was made using the fact that this transition state is know to have an 'enevelop structure', which maximises the overlap between the π systems of the two molecules. We see the ethylene slightly above (or indeed below) the plane of the butadiene.

The transition state was produced using the frozen/derivative method (used above), with an intial bond distance set at 2.2Å. Three different basis set options were utilised. These were (in order of ascending accuracy): AM1, HF and DFT. The results of the structures that they produced (along with the MO picture for the HOMO and LUMO) can be seen in the following table:

CJH_DAA_HF_MOS.LOG

| Method | AM1 | HF | DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Structure and MOs | + | + | + |

| Energy/a.u. | -231.59752 | -231.60320 | -234.54175 |

| Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

MOs Analysis of the Transition State

As can be seen from the MO plots embedded in the table above, the symmetry of the HOMO can vary based on the basis set used. For example, the AM1 method gives an anti-symmetric HOMO, whereas DFT gives a symmetric one. This shows a limitation of the AM1 system. The LUMO is always shown as being symmetric.

However in one respect the simplicity of the AM1 method is a virtue. Because it makes rather crude combinations of orbitals, it can be easier to see which orbitals are being used to build the more complex MOs. Here we can see by looking at the AM1 plots, that the LUMO is made from the combination of the symmetric ethylene HOMO, and the symmetric butadiene LUMO. The reverse must be true for the TS HOMO, with the antisymmetric ethylene LUMO mixing with the antisymmetric butadiene HOMO.

Interestingly, the DFT uses the symettric orbitals to make its HOMO for the TS. This disparity is most likely due to the fact that the orbitals will have different energies, and hence be ordered in a different way, giving a different HOMO.

Reaction Between Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

This reaction is an example of a facile Diels-Alder process, due to the fact that maleic anhydride is such a good dieneophile. What is of more interest here is that there are two possible products that can be formed (endo or exo forms), and the ratio of the formation of these products is under some form of kinetic control. This control is often explained, somewhat euphemistically, as 'secondary orbital overlap'. The techniques demonstrated in the last section, particularly in terms of the generation of MOs for the transition state will be very useful in investigating this phenomenon.

Optimising the reactants

As for the prototype reaction, it is obviously very important to pre-optimise the reactants (cyclohexa-1,3-diene and maleic anhydride). It is also useful to have known what the HOMO and LUMO of each molecule looks like:

Maleic anhydride: HOMO (symmetric), LUMO (antisymmetric)

Cyclohexa-1,3-diene: HOMO (antisymmetric), LUMO (symmetric)

DO BUTTONS

It can be seen that, as before, we can expect a HOMO - LUMO based reaction due to symmetry arguements. If the HOMO of this process belongs to the diene, then we would expect an antisymmetric TS, the reverse would be true if the HOMO is that of that of anhydride dienophile.

Optimizing the Transition State: Endo and Exo

To determine which of the reactants is providing the HOMO and which the LUMO, we can plot the MOs for various optimised transition states. Since the frozen/derivative bond method worked well for the last section, it makes sense to continue to use it. The initial guess distance was again 2.2Å As above, three methods (AM1, HF and DFT) have been used. The results were are follows:

For Endo

| Method | AM1 | HF | DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Structure and MOs | + |

+ |

+ |

| Energy/a.u. | -0.05150 | -605.61037 | -612.49548 |

| Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

For Exo

| Method | AM1 | HF | DFT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimized Structure and MOs | + | + | + |

| Energy/a.u. | -0.05042 | -605.60359 | -612.49098 |

| Imaginary Frequency/cm-1 |

We can see from this information that symmetry arguements (as discussed above) mean that the HOMO must be coming from the diene. This is because all the forms are antisymmetric. Conservation of symmetry is expected, so two antisymmetric orbitals must be combining to give these orbitals.

In this reaction the HOMO of the TS is the LUMO of the anhydride overlaping with the HOMO of the diene. This is expected, as the dienophile has a low lying LUMO (due to the stability imparted in the molecule from the conjugation with the carbonyl p-orbitals) and the diene has a comparatively high HOMO. This closeness in orbital energies should ensure a strong overlap.

We see imaginary frequencies, with vibrations that seem to resemble the bond breaking/formation we expect here. This confirms that we have the correct transition state.

We can see that there is very little difference between the energies of the two states, reinforcing the fact that the reaction is under kinetic rather than thermodynamic control.

MOs Analysis of the Transition State: Secondary Orbial interactions

It is difficult to discern much in the way of secondary orbital interactions in the HOMO or LUMO (as plotted above) for either the endo or exo form of the TS. This could be due to a number of reasons, it is entirely possible that the orbitals have been placed at a higher energy by Gaussian. To see if this is the case, we can compare the LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 for the endo and exo forms.

, , ,

Looking closely at the LUMO+2 orbitals in particular, we can see that there is a suggestion of some of the expected interactions between the carbonyl groups of the anhydride, and the developing п system at the back of the diene for the endo TS. This is completely absent from the exo version. How can the carbonyls and the п system be expected to interact when they are at opposite ends of the structure? This explains the endo-selectivity that we see for this process.

Conclusions

This investigation has shown how effective computational techniques can be in analysing the way in which transition states form for pericyclic reactions. For these reactions the transition state is very important, since bond formation/breaking should be concerted, and the MO orbitals are extremely important in determining how the reaction takes place (with particular reference to symmetry). The usefulness of having a wide range of calculation methods (AM1, HF and DFT) can be seen in terms of doing operations with different levels of complexity.

The calculations seem to have been broadly successful, with relatively accurate results obtained for the energy values in the Cope rearrangement. The work on Diels-Alder processes showed the usefulness of calculating and plotting MOs. This helped to explain the selectivity (endo/exo) that we see for the reaction.

References

- ↑ B. G. Rocque, J. M. Gonzales, H. F. Schaefer, Mol. Phys., 2002, 100, pp. 441-446.[1]

- ↑ G. Schultz, I. Hargitta, J. Mol. Struc., 1995, 346, pp. 63-69

- ↑ G. Schultz, I. Hargitta, J. Mol. Struc., 1995, 346, pp. 63-69

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M. J. Goldstein, M. S. Benzon, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1972, 94, 7147. DOI:10.1021/ja00775a046