Rep:Mod3:cb208

Module 3: Transition States and Reactivity

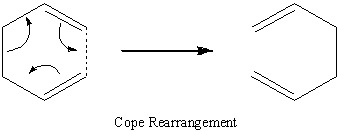

The Cope Rearrangement

Introduction

The Cope rearrangement is a [3,3]- sigmatropic shift reaction, which has been subject to many computational and experimental studies[1]. This is a particularly unusual reaction because the reactant and the product are the same (1,5-hexadiene).

The reaction mechanism (concerted, stepwise or dissociative) was an area of controversy, but is now accepted to be concerted reaction, where one σ-bond is broken while another is simultaneously formed. This rearrangement progresses via either a chair or boat transition state, where the boat transition state is slightly higher in energy.

In this experiment the reactions potential energy surface (minima and transition states) will be explored using computational techniques (the B3LYP method and 6-31G basis set), on Gaussian.

Optimizing the Reactants and Products

The aim of this section is to compare the energies for the possible conformations of 1,5-hexdiene, which has five C-C bonds (of which three have free rotation). The kinetics of the Cope rearrangement can be better understood by characterizing the most likely conformers before investigating the transition state.

Parts A to E

A structure of 1,5-hexdiene was drawn in GaussView, and its dihedral angles edited to form various anti and gauche conformers. The structures of these conformers were then optimized using the HF method and 3-21G basis set, with the final energy and symmetry being recorded. They have also been identified in comparison to the conformers on the reference table.

| Part A | Part B | Part C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy / a.u. | -231.6925353 | -231.6896157 | -231.6926612 |

| Point Group | Ci | C1 | C1 |

| Conformer | anti2 | gauche5 | gauche3 |

| Relative Energy / kcal/mol | 0.08 | 1.91 | 0 |

| Structure |

It is generally expected that the anti conformers should be lower in energy than the gauche conformers; because the anti conformer keeps the carbon atoms as far away from each other as it can, mimizing steric interactions. This relationship can be seen between the energies of anti2 and gauche5 calculated above, however it can also be seen that gauche3 is slightly lower energy than anti2, and so another stabilizing interaction must be present. This stabilization is thought to be due to a favourable C-H σ* to C-C π overlap being possible in this conformation[2], as well as the presence of stabilizing Van der Waals interactions between the H atoms at certain distances.

Parts F and G

Comparison of Different Calculation Techniques

The optimized anti2 conformer was optimized again using the more complex method and basis set of B3LYP/6-31G. This is done because although it is not expeceted to alter the geometry significantly, a more accurate calculation for the energy of a conformer is better when making predictions about a reaction.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | Bond Length / Å | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | Bond Angle / ° | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | Dihedral Angle / ° | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy / a.u. | -231.6925353 | -233.3363367 | C1=C2 | 1.31(613) | 1.33(174) | C1-C2-C3 | 124.8(06) | 124.8(04) | C1-C2-C3-C4 | -114.669 | -115.002 |

| Point Group | Ci | Ci | C2-C3 | 1.50(891) | 1.51(054) | C2-C3-C4 | 111.3(49) | 111.5(49) | C2-C3-C4-C5 | -180 | -180 |

| Structure | C3-C4 | 1.55(275) | 1.56(157) | C3-C4-C5 | 111.3(49) | 111.5(49) | C3-C4-C5-C6 | 114.669 | 115.002 | ||

| C4-C5 | 1.50(891) | 1.51(054) | C4-C5-C6 | 124.8(06) | 124.8(04) | ||||||

| C5=C6 | 1.31(613) | 1.33(174) |

Overall the geometry changes very little when optimized using the different methods and basis sets. There is no visible difference between the two structures. Measurements from GaussView can show the slight differences in the strucutres, with dihedral angles varying by less than one degree and bond angles by at most 2 degrees (all bigger in the B3LYP/6-31G method). The bond lengths are again almost identical (varying by upto 0.2Å), but it can be seen that the B3LYP/6-31G gives slightly longer bond lengths in all cases than HF/3-21G, both cases give almost identical results to that in literature[3].

It is expected that the angles and bond lengths present in the B3LYP/6-31G are calculated to reduce steric hinderance, however it is difficult to confirm this. Due to both strucutres giving almost identical results, which both match well to literature, it is impossible to say which is better to use; both give accurate results in the case of 1,5-hexadiene.

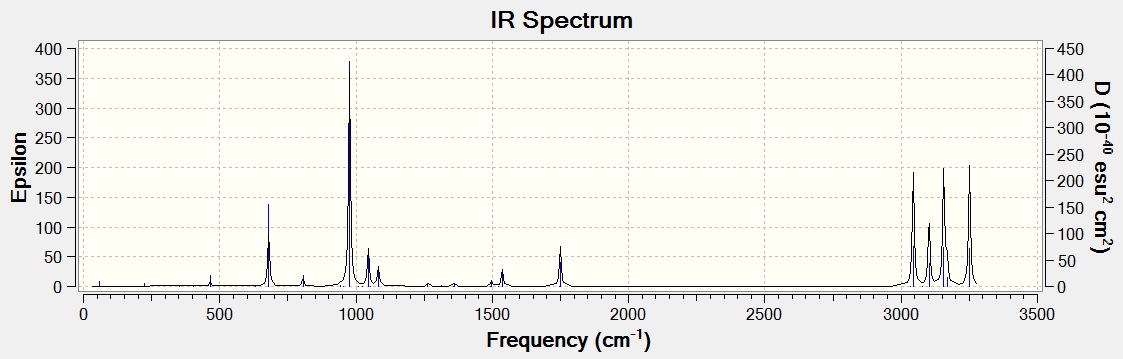

Frequency Analysis

A frequency analysis was carried out on the B3LYP/6-31G optimized structure to confirm that the optimized geometry was at a minimum and not a maximum (transition state) on the potential energy surface. All vibrational frequencies were found to be positive, showing that this was the case. Some of these vibrational frequencies and the IR spectrum are shown below.

| Vibration | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1749(.52) | 19(.5254) | Asymmetric C=C stretch | |

| 3044(.39) | 57(.0076) | Alkane C-H stretch | |

| 3102(.30) | 34(.0213) | Alkane C-H stretch | |

| 3155(.83) | 57(.6279) | C-H stretch | |

| 3168(.44) | 13(.6226) | Alkene C-H stretch | |

| 3250(.68) | 58(.6921) | Alkene C-H stretch |

The output file contains some important thermochemistry data.

| Energy | Value / a.u. |

|---|---|

| Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies | -234.415982 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Energies | -234.409379 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies | -234.408435 |

| Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies | -234.446849 |

The 'Sum of electronic and zero-point Energies' is the potential energy at 0K, which includes the zero point vibrational energy (E = Eelec + ZPE).

The 'Sum of electronic and thermal Energies' is the energy at standard conditions (298.15k and 1 atm pressure), it includes the contributions from translational, rotational and vibrational modes (E = E + Etrans + Erot + Evib).

The 'Sum of electronic and thermal Enthalpies' is particuarly important when looking at dissociation reactions, and contains an extra correction for RT (H = E + RT).

The 'Sum of electronic and thermal Free Energies' includes the entropic contribution to free energy (G = H - TS).

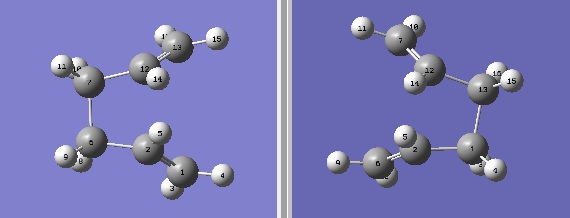

Optimizing the "Chair" and "Boat" Transition Structures

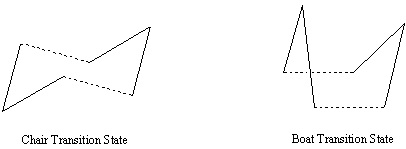

Computational technquies can be used to model and investigate the transition states in reactions. There are two possible transition state geometries in the Cope rearragement, the chair and the boat.

The Chair Transition State

In order to model the chair transition state; a CH2CHCH2 fragment was drawn in GaussView, and optimized using the HF method and 3-21G basis set. This optimized fragment was then duplicated and arranged to a chair conformation with the terminal carbon atoms separated by a distance of 2.2Å.

It should be noted that these structures appear as resonance structures in GaussView and do not have defined single/double bonds.

This chair transition state was then optimized using two different methods. First using the TS(Berny) method, where a force constant matrix is calculated and then recalculated throughout the optimization. The initial guess of this matrix has to be accurate due to the sensitivity of this method to the input geometry, if it is a poor intial guess then the potential energy surface calculated would be different from the actual one, thus giving an incorrect transition state structure. The second is the Frozen Coordinate method, where the reaction coordinate is frozen and the rest of the molecule is optimized, the molecule is then unfrozen and the transition state optimized again. The main advantage of this method is that the entire Hessian does not need to be calculated.

TS(Berny) Method

An “opt+freq” calculation was set up to optimize to a TS(Berny), rather than a minimum, and to calculate force constants once. The addition keywords “opt=noeigen” were also added to ensure the calculation did not crash if more than one imaginary frequency was found.

The optimized transition state was found to have a terminal C-C bond length of 2.02(029) Å. The frequency analysis confirmed that the optimized structure was indeed a transition state from its negative (imaginary) vibrational frequency at 817.85cm-1 (identical to that expected). This vibration corresponds to Cope rearrangement, the connection/disconnection of the appropriate bonds. The vibration is asymmetrical with one bond being formed as the other is broken, suggesting this process is a pericyclic reaction.

Frozen Coordinate Method

In this method the distances between the terminal carbons was initially fixed at 2.2 Å by using the “redundant coordinate editor” to freeze these atoms in place, while the rest of the molecule was optimized. These distances were then “unfrozen” and the molecule optimized again. This method is particularly useful when running a calculation where the force constant approach would be very time consuming; because this method only requires the Hessian to be calculated along the reaction coordinate.

This method gave very similar results as above, with bond lengths of 2.01(884) Å, showing that the same transition state has been calculated in both cases. This suggests a high level of accuracy in the optimization, but this is likely to be due to the high level of accuracy of the input structure. The first method requires the input to be very similar to that of the desired transition state, and the second method requires a very good initial guess for the terminal distances.

It was found that for the frozen coordinate method that the optimization had to be set to “TS(Berny)” and not minimum and the key words “opt=noeigen” had to be included or the calculations would fail and give the wrong structure.

The Boat Transition State

The QST2 method was used to optimize the boat transition state. This is where the reactants and products are specified for a given reaction and the calculation will determine the transition state between them. The optimized “anti2” structure from before was introduced into GaussView as both the reactant and product in a MolGroup, and the atoms labelled so they correspond to the desired reaction. Unfortunately both the reactant and product structures have to be drawn close to the transition state, shown by the failure of the calculation when both were left in the anti conformation. Instead they both needed to be modified so that they are closer to the structure of the boat transition state. The dihedral angle of the central four carbon atoms was set to 0ᵒ (from 180ᵒ), and the inside C-C-C angles set to 100ᵒ (from 111ᵒ), for both the reactant and product. The outcome of this is shown below.

It was found that the calculation also failed unless the both input structures were “symmertrized” first.

The optimized boat transition state was found to have an energy of -231.60280229 a.u., a terminal C-C distance of 2.14(008) and one negative frequency (confirming a transition state) at -839(.73) cm-1, which again corresponds to the bond formation within the cope rearrangement.

The QTS3 method, in which a guess transition state is also input into the calculation (which should give better results), was also run. However it gave almost identical results for the energy, terminal C-C distance and negative vibration, showing that QTS2 is accurate enough for this exercise.

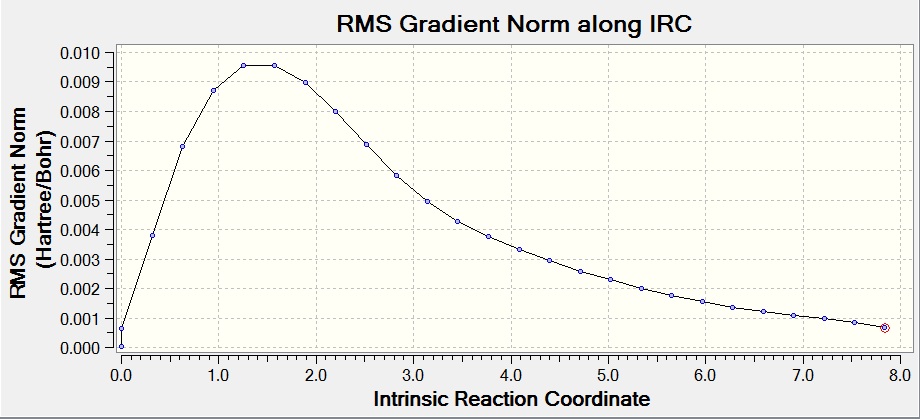

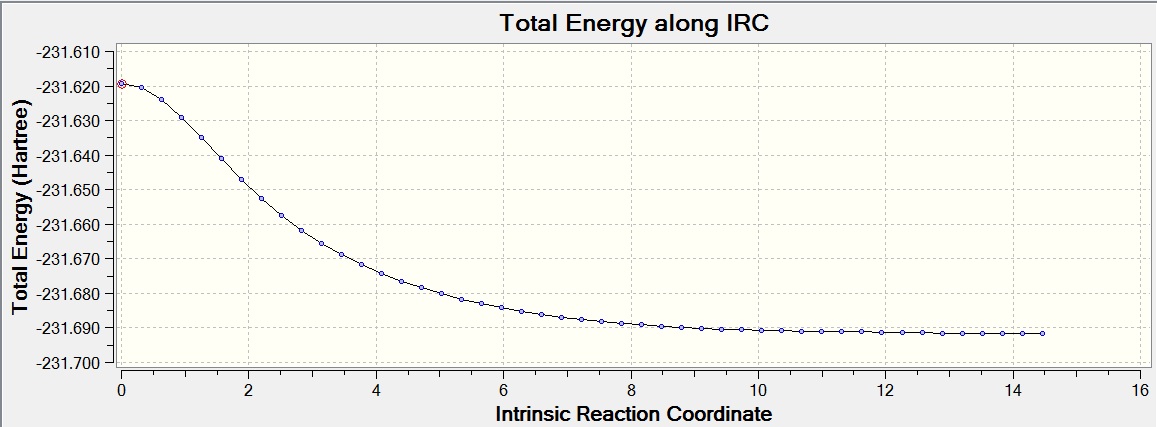

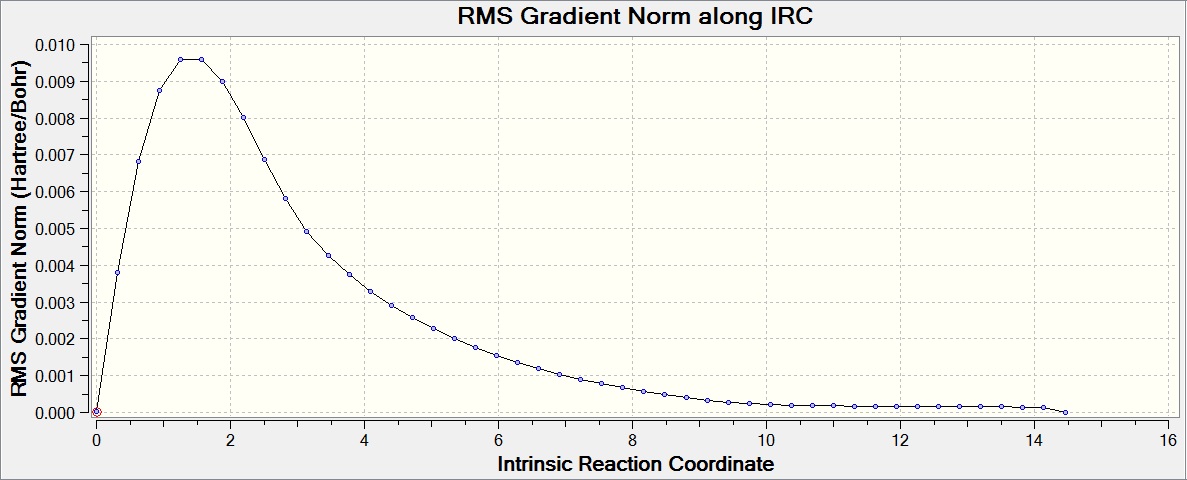

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) Method

The IRC method allows you to follow the minimum energy pathway from a transition state to its local minimum on a potential energy surface. A series of points are created by making small changes to the geometry in the direction of the steepest gradient, leading to the conformer the transition state would go to. The calculation was run on the chair transition state that had been optimized by HF/3-21G, with 50 points on the IRC pathway and the force constants only calculated at the start.

This calculation can be seen to have not yet reached a minimum, and thus a conformer of 1,5-hexadiene has not yet been found. The final energy calculated was -231.68864179 a.u., after 27 steps.

To find a better minimum the calculation was repeated, but the method changed to calculate the force constant at every step, allowing the calculation to tell if it is moving down the minimum energy pathway at all times and change the pathway when necessary. The final energy calculated was -231.69166433 a.u., showing that the transition state has formed the gauche2 conformer (after 47 steps).

Activation Energies For The Transition States

The HF/3-21G (TS(Berny)) were compared to those optimized using B3LYP/6-31G(d) (calculated from the optimized HF/3-21G structures). The thermochemistry results from these optimizations were then used to find the activation energies for each transition state calculated. The energies of the starting “anti2” conformer and both the chair and boat transition states were calculated at 0 and 298 K (found in the “thermochemistry” section of the log file).

| HF/3-21G | HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | B3LYP/6-31G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | Electronic Energy | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | |

| at 298.15K | at 298.15K | |||

| Reactant (anti2) | -231.6925353 | -231.532565 | -234.6117104 | -234.461857 |

| Chair TS | -231.6193224 | -231.461339 | -234.5569828 | -234.40901 |

| Boat TS | -231.6028023 | -231.445298 | -234.543093 | -234.396005 |

There is a clear difference in energy between the two methods, however because two different methods have been used it is not possible to directly compare the results. Instead the activation energies are calculated for each transition state, by comparing the energies in the table above with that of the optimized reactant. The activation energy is calculated in kcal/mol for comparison with the experimental results given.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | Experimental | |

|---|---|---|---|

| at 298.15K | at 298.15K | at 0K | |

| ΔE Chair | 45.8892 | 33.29361 | 33.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol |

| ΔE Boat | 55.82493 | 41.48676 | 44.7 ± 2.0 kcal/mol |

These activation energies show that the B3LYP/6-31G results are in good agreement with the experimental values, the HF/3-21G results are not comparable (as a lower level calculation has been used) but can be seen to be roughly 10 kcal/mol higher than the experimental values. Both sets of values are in agreement with those seen on the example table in wiki.

The results clearly show that the chair transition state has a lower activation energy than the boat (due to less steric hinderance), and so is the expected transition state in the Cope rearrangement.

The Diels Alder Cycloaddition

The Diels-Alder reaction is a [4π + 2π] pericyclic cycloaddition reaction between a conjugated diene and a dienophile (an alkene). These reactions have no intermediate species and just one transition state. This transition state is stabilized by containing six delocalised electrons (giving some aromatic character).

The HOMO/LUMO of the diene reacts with the HOMO/LUMO of the dienophile to form two new σ bonds. The number of π electrons involved in these pericyclic transition states control if the reaction proceeds via a concerted stereospecific way or not, allowed or forbidden.

The simplest example of a Diels-Alder reaction is that of ethylene and cis-butadiene, which will be investigated first. Then the stereoselectivity of a Diels-Alder will be studied by looking at the reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride. The optimization calculations will be run using the semi-empirical AM1 method, followed by B3LYP/6-31G to find the properties of the reactants and transition states, predicting the reaction path.

Ethylene and cis-Butadiene

Ethylene and cis-butadiene undergo the following Diels-Alder reaction to form cyclohexene.

Reactants

Ethylene and cis-butadiene were optimized using the semi-empirical AM1 method, and the HOMO and LUMO generated for both. The energy of optimized ethylene was 0.02619024 a.u. and for optimized cis-butadiene 0.04879719 a.u.

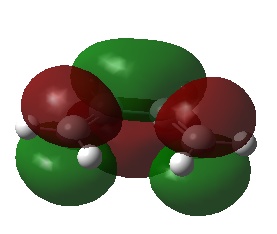

| Reactant | Molecular Orbital | Picutre | Symmetry | Energy / a.u. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

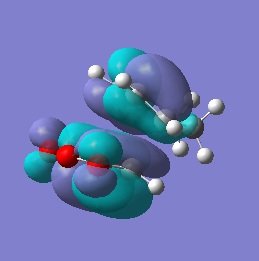

| Ethylene | LUMO |  |

Anti-symmetric | 0.05284 |

| HOMO |  |

Symmetric | -0.38777 | |

| cis-Butadiene | LUMO |  |

Symmetric | 0.01707 |

| HOMO |  |

Anti-symmetric | -0.34381 |

It can be see that the symmetries for the HOMO and LUMO are opposite for ethylene and cis-butadiene. The HOMO ethylene will react with the LUMO of cis-butadiene and the LUMO of ethylene with the HOMO of cis-butadiene (due to the conservation of orbital symmetry). Orbital symmetry is very important in pericyclic reactions, because it determines if the reaction occurs at all and the reactions stereochemistry.

Transition State

In order to calculate the transition state, the frozen coordinate method described previously was used. First the optimized reactants were moved into the geometry predicted for the transition state, to maximize orbital overlap. The terminal C-C bonds were frozen at 2.05 Å and an optimization run using the AM1 method. This optimized structure was then optimized (AM1) to a TS(Berny), with the frozen bonds unfrozen. Finally the structure was optimized again, to a TS(Berny), using B3LYP/6-31G(d). Both the optimizations with AM1 and B3LYP/6-31G(d) gave one negative frequency, confirming that a transition state was successfully found, both looking the same visually.

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G(d) | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy / a.u. | 0.11165527 | -234.5438954 |

| Frequency / cm-1 | -957.21 | -524.59 |

| Vibration |  |

|

| C-C Bond Forming Length / Å | 2.11(920) | 2.27(288) |

It is not possible to compare the energies from the two methods, as each is reported differently. However, a difference between the methods can be seen in the C-C forming bond lengths, where the more accurate B3LYP/6-31G(d) method gave slightly longer (≈0.15Å) bond lengths. The negative frequencies also appear at very different places, also due to the different methods used, but because they are imaginary frequencies their value is fairly useless anyway. Both the vibrations are identical, and correspond to the concerted formation of two C-C bonds (as expected from a Diels-Alder reaction).

The C-C (1.38Å) and C=C (1.40Å) in the transition states are between those expected for C-C (1.30Å) and C=C (1.54Å) bonds. This suggests that π bonds are breaking and donating electron density to the σ bonds, the double bond are becoming single bonds (and vice versa), showing the aromatic character of the transition state.

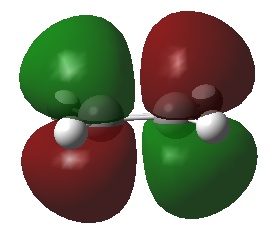

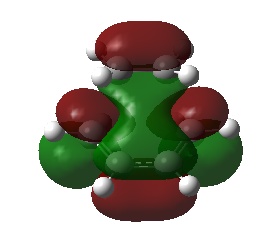

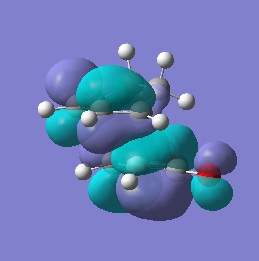

The HOMO and LUMO of the transition state can be seen below.

| Molecular Orbital | Picutre | Symmetry | Energy / a.u. |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUMO |  |

Symmertric | 0.02315 |

| HOMO |  |

Anti-symmertric | -0.323 |

The HOMO of the transition state is formed from the overlap of the LUMO of ethylene and the HOMO of cis-butadiene, and shows the σ bonding orbitals of the C-C bonds formed in the reaction. The LUMO of the transition state is formed from the HOMO of ethylene and the LUMO of cis-butadiene, it shows the σ* antibonding orbitals. This analysis is in agreement with the conservation of orbital symmetry, which states that the symmetry of an orbital formed must be the same as those that formed it.

Activation Energy

The reactants were optimized again using B3LYP/6-31G to make comparisons to the transition state energy. Then the activation energies were calculated and compared to the literature[4] value of 115kJ/mol (at 0K).

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G | |

|---|---|---|

| Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | Sum of Electronic and Thermal Energies | |

| at 298K | at 298K | |

| Ethylene | 0.080255 | -78.533177 |

| cis-Butadiene | 0.1402 | -155.896785 |

| Reactant Total | 0.220455 | -234.429962 |

| Transition State | 0.259451 | -234.396906 |

There is a clear difference in energy between the two methods, however because two different methods have been used it is not possible to directly compare the results. Instead the activation energies are calculated for each transition state, by comparing the energies in the table above with that of the optimized reactants. The activation energy is calculated in kJ/mol for comparison with the experimental results.

| AM1 | B3LYP/6-31G | Experimental | |

|---|---|---|---|

| at 298K | at 298K | at 0K | |

| Activation Energy / a.u. | 0.038996 | 0.033056 | N/A |

| Activation Energy / kJ/mol | 101.3896 | 85.9456 | 115 |

| Activation Energy / kcal/mol | 24.56748 | 20.82528 | N/A |

Surprisingly these results suggest that the lower level of calculation (AM1) is a better fit with the experimental results. However, both results are still only a reasonably good fit with those from literature.

Cycloaddition of Cyclohexa-1,3-diene and Maleic Anhydride

The reaction of cyclohexa-1,3-diene with maleic anhydride is another example of a Diels-Alder reaction. Unlike the previous reaction, there are now two potential products, the exo and endo products. The endo and exo products are stereoisomers, and which is formed is dependent on the direction of the attack by the dienophile on the diene, the endo product is known to be the major product in this reaction. This is explained by the endo rule, which states that the transition state leading to the endo product is lower in energy than the transition state leading to the exo product (which will be tested here).

Optimisation of the endo and exo Transition States

The guess transition states were created and then optimized using the same method as the Diels-Alder above. The reactants were first optimized using AM1, moved into a single window and then arranged into a similar geometry of the expected transition states (exo and endo). These were then optimized using the frozen coordinate method, with an initial frozen coordinate length of 2.2 Å. After unfreezing the bond forming carbons the transition state was optimized again to a TS(Berny), they were then optimized again using the more accurate method of B3LYP/6-31G(d).

The frequency analysis calculated just one negative frequency for each calculation, confirming that a transition state had been found in each case. The vibration shows a concerted formation of two new C-C bonds (as seen in the previous Diels-Alder reaction), this is as expected. The differences in the vibrational frequency values are for the same reasons discussed before.

It is expected that the less sterically hindered exo product would be the thermodynamic product (and so the major product), however, the Diels-Alder reaction is controlled kinetically, and so the major product is determined by the relative transition state energies. The endo transition state is found to be lower in energy (by 0.004087 a.u.), and so as the lowest energy route should lead to the major product, this is in agreement with experimental results[5]. The stability of the endo transition state is explained using the secondary orbital overlap between the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment and the new C=C bond, this interaction is not present in the exo product.

The bond lengths are very similar in both transition states, with the endo having the slightly smaller C-C bond forming distance (possibly due to the secondary orbital interaction).

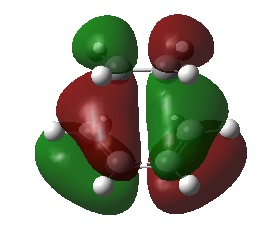

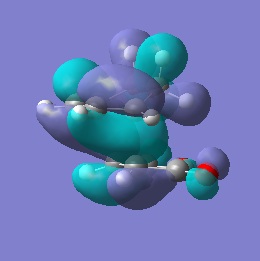

The HOMO and LUMO orbitals for both transition states can be seen below, to help explain the secondary orbital interaction.

| Endo | Exo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Orbital | Picture | Energy / a.u. | Symmetry | Picture | Energy / a.u. | Symmetry |

| LUMO |  |

-0.067 | Anti-symmetric |  |

-0.078 | Anti-symmetric |

| HOMO |  |

-0.242 | Anti-symmetric |  |

-0.242 | Anti-symmetric |

From the molecular orbitals above (all anti-symmertric), the HOMO describes the forming of the σ bonds between the reactants (shown by the electron density between the bond forming C-C), the LUMO orbitals are out of phase between the reactants. It can be seen that the HOMO of the transition state has been formed by interaction of the dienophile LUMO and diene HOMO.

The endo selectivity of the Diels-Alder reaction is explained by the secondary orbital overlap, between the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment and the new C=C bond. This interaction is only possible in the endo transition state as seen in the following diagram.

The above diagram suggests that a bonding interaction should be seen between the (O=C)-O-(C=O) fragment and the new C=C bond in the endo transition states HOMO, but a node is present instead. This discrepancy with theory is most likely due to the low level theory (AM1) being used to generate the molecular orbitals.

Activation Energies

The activation energies for each transition state were calculated using both AM1 and B3LYP/6-31G.

| HF/3-21G | B3LYP/6-31G | |

|---|---|---|

| at 298K | at 298K | |

| endo Activation Energy / a.u. | 0.089879 | 1.234681 |

| exo Activation Energy / a.u. | 0.091078 | 1.238808 |

These activation energies show that, as expected, the activation energy for the endo transition state is lower than that of the exo transition state. Further confirming that as the reaction is under kinetic control that the endo product will dominate.

Conclusion

This lab showed the usefulness of computational techniques in modelling transition states in reactions, including their vibrations and molecular orbitals. This allows predicted outcomes of reactions to be determined, for both thermodynamically and kinetically controlled reactions (shown by the proof of endo selectivity).

As computational chemistry is a relatively new area of chemistry there are still errors associated with the calculations and limitations to what can be done. The major limitation is that while the energy of both the transition states and products can be calculated computational techniques are not able to tell you if the reaction is kinetically or thermodynamically controlled (this can only be found experimentally).

References

- ↑ Wiest, O. et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1994, 116(22), 10336-10337. [1]

- ↑ Rocque, B. et al. Mol. Phy., 2002, 100, 441-446. [2]

- ↑ Schultz, G. Hargittai, I. J. Mol. Struc., 1995, 346, 63-69 [3]

- ↑ Hoffmann, R. Woodward, R. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87(19), 4388-4389. [4]

- ↑ Alder, K. Stein, G. Angew. Chem., 1937, 50, 510