Rep:Mod2jsm108

Josh Stephen McNicoll 00551754

Introduction

Bonding in inorganic chemistry is not as straight forward as in organic chemistry. The object of this project is to use inorganic systems to compute properties such as IR spectra, dipole moments and also relative conformer energies. Electron density analysis also gives us information about the bonding and interactions in molecules. These skills are shown in the following report, along with original research in the mini project.

BH3 molecule

Optimisation

BH3 was drawn in GaussView and all three B-H bond lengths were set to 1.5 angstrom. The molecule was then optimised (with the method and basis set displayed in the table below). https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Image:BH3_OPTjsm108.LOG

Lowest conformation structure |

The following values were established:

Optimum B-H bond distance: 1.19 A

Optimum H-B-H bond angle: 120.0°

Results:

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 3-21G |

| Final energy (au) | -26.46 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00021 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0.0 |

| Point group | D3H |

| Job time | 3 minutes 2.0 seconds |

The gradient is smaller than 0.001, and so the optimisation completed successfully.

Literature bond distance = 1.1867 [1]

This compares very well with the computed bond length from the optimisation. The angle that was computed fits with the angle for the trigonal planar structure.

Molecular orbitals

The molecular orbitals for the BH3 molecule were calculated and displayed below DOI:10042/to-5743 :

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These MO's were then added to a valence MO diagram for BH3:

As seen from the diagram, the computed MOs match very well with the LCAO MOs. This shows that the qualitative MO theory used to draw the valence MO diagram is actually very useful and accurate to determining the MOs of this molecule. It is also has the advantage of being quicker and easier to use, and does not require any calculations. However, I believe that there will become a point where molecules become more complicated and the MO theory starts to move away from the computed MOs of the molecule. But, at this level of molecule, the MO theory is sufficiently accurate.

NBO analysis

The NBO analysis of the BH3 molecule is shown below:

|

In the diagram to the left the atoms are colour coded- green indicates highly positive charge and bright red highly negative charge.

The diagram to the right shows quantitative values for this, instead of colours.

The result matches well with my predictions- boron is positive and hydrogen is negative.

Vibrational analysis and confirming minima

The vibrations of the optimised BH3 molecule were calculated using the following data: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Image:JSM108_BH3_FREQ.LOG

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 3-21G |

| Final energy (au) | -26.46 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0.00 |

| Point group | D3h |

| Job time | 0 minutes 22.0 seconds |

It is known that molecules have 3N-6 vibrational frequencies, and so for my molecule, it is expected that 6 vibrational frequencies are calculated. This is certainly the case and the results are displayed in the table below:

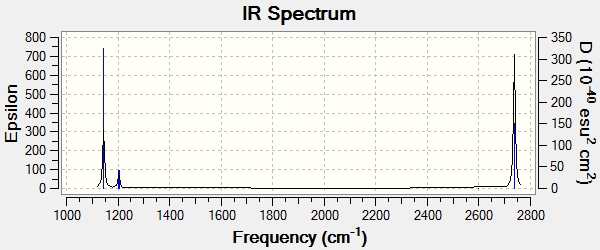

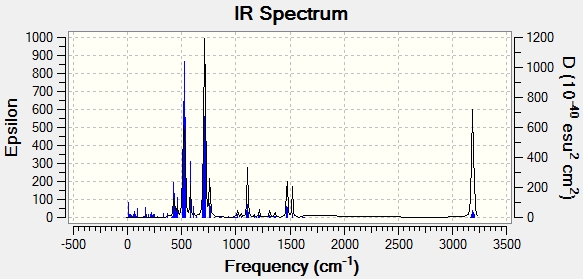

The IR spectrum has also been calculated:

There are only 3 peaks in the IR spectrum, as opposed to 6 peaks. This can be explained by looking at the vibrations. Vibration 4 has an intensity of 0 and so is not seen in the IR spectrum. Looking at the vibration, it is symmetrical (symmetry point group= a'1). This renders the vibration IR inactive because there is no change in molecular dipole moment. This leave 5 vibrations. However, there are 2 sets of degenerate vibrations (symmetry point group= e'). This means that each set of degenerate vibrations corresponds to only one peak in the spectrum. The first vibration is IR active and so is seen as a peak.

In addition to this, the "low frequencies" can be taken from the log file:

-69.0233 cm-1

-66.0138 cm-1

-64.7529 cm-1

-0.0003 cm-1

-0.0001 cm-1

0.0005 cm-1

Although these values are not within plus or minus 10cm-1 to 0, they are at an acceptable level due to the low level calculations.

TlBr3 molecule

Optimisation

A TlBr3 molecule was drawn in GaussView, and the symmetry was restricted to the D3h point group, with a "very tight (0.0001)" tolerance. The molecule was then optimised (with the method in the table below) and the following results were obtained https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Image:TlBr3_optimisation_logfile_jsm108.log:

Optimum Tl-Br bond distance: 2.65 A

Optimum Br-Tl-Br bond angle: 120.0°

Lowest conformation structure |

Results:

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -91.22 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000009 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0.0 |

| Point group | D3H |

| Job time | 2 minutes 38.0 seconds |

Literature bond distance= 2.512 A [2]

The literature matches fairly well with the computed value. However, the calculation is less accurate here than with BH3 previously. The angle once again agrees with the trigonal planar arrangement. The bond distance would be more accurate if a larger basis set was used.

Vibrational analysis and confirming minima

A frequency analysis is carried out to ensure that the optimised structure that has been acheived is actually a minimum. Frequency analysis involves computing the second derivative of the potential energy surface- therefore if all vibrational modes are positive, then we have a minimum on the potential energy surface.

The vibrational modes of TlBr3 were calculated using the following data: https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Image:JSM108_TLBR3_freqjsm108.LOG

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -91.22 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000088 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0 |

| Point group | D3H |

| Job time | 0 minutes 36.0 seconds |

The same method and basis set was used for the vibrational analysis that was used for the optimisation so that you can compare the results. The vibrational analysis is only accurate if the same method is used.

The "low frequencies" for TlBr3 are as follows:

-3.4213 cm-1

-0.0026 cm-1

-0.0004 cm-1

0.0015cm-1

3.9367 cm-1

3.9367 cm-1

All the frequencies are with 10 cm-1 of 0, and are therefore within the threshold needed for an accurate calculation.

The results for the "real" modes are summarised in the table below:

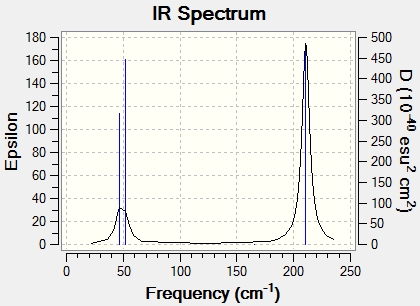

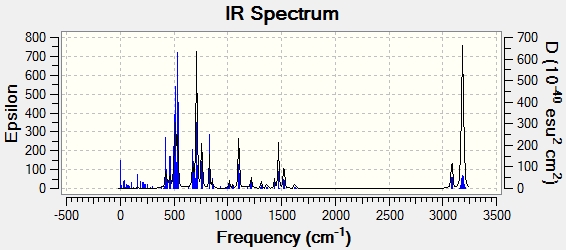

A copy of the IR spectrum produced is shown:

What is a bond

A bond is a type of attraction between species. These bonds can for example be ionic (electrostatic) or covalent in nature. It is a lot easier to define bonds in organic systems than in inorganic systems. In inorganic systems, bonding is usually not as simple as single and double bonds, or σ and π bonds, especially in transition metal chemistry with metals and ligands. Drawing bond with lines is an easy way to represent molecules for us, and it also serves as a way of drawing and communicating chemistry. Gaussview draws bonds to predetermined distances, but when a file is created in Gaussview to run a calculation, only the co-ordinates of species are given in the file, not where one has drawn bonds. Bonds can also vary largely, and so predetermined distances will not take into account every bond there could be. This shows that the bonds are simply for illustrative and drawing purposes, for our benefit. The bonds can be thought of attractive forces in the molecule between certain species, holding the molecule together- this can be rationalised with MO theory and MO calculations. However, I personally cannot think in molecular orbitals, and so drawing bonds is a very effective short-hand version.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Optimisation

The cis and trans isomers of the complex were optimised with the following methods:

TRANS DOI:10042/to-5912

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2MB |

| Final energy (au) | -617.52 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000062 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0.00 |

CIS DOI:10042/to-5913

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2MB |

| Final energy (au) | -617.53 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000008 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 8.63 |

The dihedral angles were then changed, along with the basis set, and the molecules were re-optimised:

TRANS DOI:10042/to-5914

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -623.58 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000031 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 0.31 |

CIS DOI:10042/to-5917

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -623.58 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000046 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 1.31 |

Optimised molecules:

TRANS

Lowest conformation structure |

CIS

Lowest conformation structure |

Cis Mo-P bond length= 2.51 A

Trans Mo-P bond length= 2.44 A

Literature bond length= 2.4442 A[3]

As seen form the bond lengths, both cis and trans bond distances match well with the literature value. Mo-P bond lengths in the literature are from the complex [Mo(CO)5P(OH)3] and so bond lengths are not expected to match exactly. It can be seen that the Mo-P bond length is slightly longer for the cis isomer. This is probably due to steric strain between the PCl3 groups because they are next to each other in the cis complex.

It can also be seen that the energies of the molecules are very close. If the full value for the energy is taken, it can be seen that the cis isomer is the more stable isomer:

Cis isomer

-623.57707173 a.u.

Trans isomer

-623.57603102 a.u.

It can be seen that the cis isomer is more negative than the trans isomer, by 0.00104071 a.u. This means that the cis isomer is more stable than the trains isomer. This is equivalent to 2.73 kJ/mol-1 the isomerisation energy. This is a small energy difference, and cannot be deemed as accurate due to the error associated with these calculations (10 kJ/mol-1).

The cis isomer may be more stable than the trans isomer due to the trans effect. The PCl3 ligands are trans to CO ligands in the cis complex, whereas they are trans to each other in the trans complex. The arrangement for the cis is beneficial to the molecule, overcoming the higher steric hindrance of placing the groups next to each other, and ultimately stabilising the molecule.

Changing the nature of the PR3 ligand can change the ordering of the cis and trans energies. By increasing the bulk of the R groups on the ligands (with perhaps Ph groups) the steric repulsion in the cis isomer will overcome any stabilisation and render the cis isomer less stable. However, decreasing the bulk (with perhaps Me) would cause less steric hindrance between the groups in the cis isomer, and allow the stabilisation to lower the energy of the cis isomer, causing it to be more stable than the trans isomer.

Vibrational analysis and confirming minima

The vibrations for the cis and trans isomers were calculated. All vibration frequencies were positive, leading to the conclusion that the molecules are indeed in a minimum.

The following results were obtained:

Trans isomer DOI:10042/to-5918

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -623.58 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000031 |

| Dipole moment (debye) | 0.31 |

Cis isomer DOI:10042/to-5919

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| Final energy (au) | -623.58 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.000047 |

| Dipole moment (debye) | 1.31 |

The IR spectra for both isomers are displayed below:

Each isomer had 2 vibrations are very low frequencies, which are illustrated in the table below:

| Trans | ||

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Image |

| 5 | 0 |  |

| 6 | 0 |  |

| Cis | ||

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Image |

| 11 | 0 |  |

| 18 | 0 |  |

The low frequency vibrations all relate to wagging of the PCl3 groups, and all of the vibrations have a very small intensity. At room temperature these vibrations would be occurring because there is sufficient energy at room temperature to produce these vibrations.

The CO stretching frequencies for both isomers are listed below:

| Trans | |

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

| 1950 | 1475 |

| 1951 | 1467 |

| 1977 | 1 |

| 2031 | 4 |

| Cis | |

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

| 1945 | 762 |

| 1950 | 1500 |

| 1959 | 634 |

| 2024 | 597 |

Literature CO sretches[4]

Trans 1895 cm-1

Cis 2019c m-1, 1922 cm-1,1905 cm-1,1899 cm-1

These values match fairly well with the computed values I have obtained, taking into account that the compound these stretches were taken from is slightly different from the compound I have here.

It can be seen that there are 4 stretches for the cis isomer, whereas there is only 1 stretch for the trans isomer. The trans isomer has 2 vibrations with almost 0 intensity (IR inactive) and a degenerate set, which is why only one peak is seen. The cis isomer has 4 individual single degenerate vibrations that are all IR active. IR is a great method for differentiating between cis and trans isomers in this example.

Mini Project

For the mini project I have decided to investigate the structure and bonding of square planar platinum complexes with ethylene derived ligands. The compounds I will investigate are:

My aim is to work out the C-C bond lengths in each example, the amount of back-bonding from the platinum to the alkene, and whether the alkenes sit in a metallacyclopropane arrangement.

All compounds were calculated using pseudo potentials (LanL2DZ) on the Pt and the 6-311G(d) basis set on all the other atoms.

Pt(PPh3)2(C2H4)

Optimisation

The first attempt to optimise the molecule Pt(PPh3)2(C2H4) did not yield a satisfactory result DOI:10042/to-5739 :

Lowest conformation structure |

The data summary is as shown:

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Final energy (au) | -2270.65 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000347 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 4.76 |

| Job time | 36 hours 44 minutes 30 seconds |

The original molecule was altered so that the carbons had an sp3 arrangement, and the C-C bond length was set to the value found in the literature. This was then sent for optimisation.

The optimised geometry of Pt(PPh3)2(C2H4) is illustrated below DOI:10042/to-5740 :

Lowest conformation structure |

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Total energy (au) | -2270.79 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000341 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 3.25 |

| Job time | 19 hours 54 minutes 28 seconds |

As seen, the final energy here is lower, being the more stable conformer.

The C-C bond distance for the optimised molecule= 1.42 A

Literature bond distance= 1.43 A[5]

Vibrational analysis

The first structure was sent of for frequency analysis DOI:10042/to-5775 :

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Total energy (au) | -2270.65 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000347 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 4.76 |

| Job time | 12 hours 45 minutes 16 seconds |

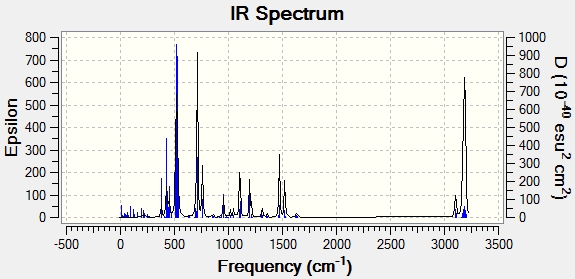

The IR spectrum produced is displayed:

An interesting thing about this analysis, is that all the frequencies that were recorded are positive values, showing that this state is actually a minimum, but a higher energy minimum.

Looking at the structure of this higher energy minimum, it can be seen that the carbons have taken more of an sp2 arrangement, almost as if the C-C bond is not registered as being present. This is the reason why the molecule was re-run to show that this is not the lowest minimum.

The second structure was sent off for frequency analysis DOI:10042/to-5908 :

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Total energy (au) | -2270.79 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000341 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 3.25 |

| Job time | 11 hours 21 minutes 4 seconds |

The IR spectrum calculated is shown below:

All of the vibrations are positive, confirming this is the lower energy minimum.

Pt(PPh3)2(C2CN4)

Optimisation

The molecule was sent for optimisation DOI:10042/to-5777 :

Lowest conformation structure |

Optimised bond distance= 1.50 A

Literature bond distance= 1.49 A[5]

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Final energy (au) | -2639.85 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000523 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 13.83 |

| Job time | 12 hours 8 minutes 13 seconds |

Vibrational analysis

The minimised molecule was sent for frequency analysis DOI:10042/to-5909 :

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Total energy (au) | -2639.85 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000052 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 13.83 |

| Job time | 17 hours 12 minutes 46 seconds |

The IR spectrum produced is displayed:

All vibrations are also positive, showing this is again a minimum.

Pt(PPh3)2(C2Cl4)

Optimisation

The molecule was optimised DOI:10042/to-5776 :

Lowest conformation structure |

Optimised bond distance= 1.48 A

Literature bond distance= 1.62 A[5]

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Final energy (au) | -4109.26 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.00000217 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 9.71 |

| Job time | 13 hours 5 minutes 0 seconds |

Vibrational analysis

The minimised molecule was sent for frequency analysis DOI:10042/to-5910 :

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | FREQ |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Total energy (au) | -4109.26 |

| Gradient (au) | 0.0000022 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 9.71 |

| Job time | 15 hours 36 minutes 50 seconds |

The IR spectrum produced is displayed:

All vibrations are also positive, again showing that this geometry is a minimum.

Analysis

| Compound | Optimised C-C bond length (A) | Literature bond length (A) | Difference from literature bond length (A) | C-C stretch frequency (cm-1) | C-C stretch intensity | Pt-(C=C) stretch frequency (cm-1) | Pt-(C=C) stretch intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free CH2=CH2 | 1.34[5] | - | - | 1623[5] | - | - | - |

| Pt(PPh3)2(C2H4) | 1.42 | 1.43[5] | 0.01 | 1196 | 57 | 377 | 21 |

| Pt(PPh3)2(C2CN4) | 1.5 | 1.49[5] | -0.01 | 1232 | 54 | 647 | 1 |

| Pt(PPh3)2(C2Cl4) | 1.48 | 1.62[5] | 0.14 | 1170 | 6 | 579 | 55 |

Alkenes bind to metal centres via synergic bonding, shown below:

It can be seen that with more back-bonding, there would be more electron density in the C-C pi* orbital. This would reduce the C-C bond order and the alkene will form more of a metallocyclopropane structure. This would weaken the C-C bond, as well as lengthening the bond. IR is a good method to show this.

It can be seen that all of the bond lengths are larger than free ethene, indicating that back-bonding exists in some form for all of the compounds. The extent of back-bonding can be worked out from the bond lengths and stretches. When ethene complexes to the platinum centre, the bond length increases and the frequency decreases relative to free ethene. This illustrates the back-bonding. The calculated bond length matches very well with the literature value.

When hydrogen is substituted for CN groups, the bond length is again longer than ethene. The calculated bond length matches very well with the literature value. This is because CN is an electron withdrawing group. This would deplete electron density in the C-C orbitals, causing more back-donation from the metal into the anti-bonding orbital of the C-C, lengthening the bond and causing the ligand to move closer to the metal centre. It was expected that the stretching frequency of the C-C would decrease due to this, however, this was not seen in the results. The stretching frequency is slightly higher than with the previous compound, even though the bond is longer. The stretching frequency does however agree with free ethene. It is still much lower than for free ethene, showing that the back-bonding has again lengthened and weakened the C-C bond.

The most likely source of this error is to do with the limitations of the calculations. "In the Pt0 complex [Pt(PPh3)2(C2CN4)], the carbon–carbon bond of the olefin is extensively lengthened and can be best represented by a metallacyclopropane structure. Most transition-metal–olefin complexes lie between these two extremes."[6]. This is a big limitation in the original structures drawn. It was not possible for me to accurately draw a complex where the alkene sits between the two states of bonding. As a result, I chose to drawn the complexes in more of a metallacyclopropane structure. Although in this instance the correct bond length was given, the stretching frequency does not seem accurate because of this. The nature of bonding may be slightly different in my structure when compared to the real complex. This is where drawing chemical bonds is a real disadvantage- bonds alone is not accurate enough to describe the bonding in this system.

Unfortunately, a stretching frequency for the C-C bond in this complex could not be found in the literature, and so no comparison could be made.

When the hydrogens were substituted for chlorine atoms, bond lengthening is seen again. However, the optimised bond length does not compare very well with the literature bond length. This is due to the same limitation as before. The IR stretching frequency is seen to follow that pattern with bond lengthening however, by decreasing in value. The extent of back-bonding is less in my optimised structure than in the real complex.

If I were to repeat the calculations, I would try starting geometries at the other extreme. I could use these calculations to see if the final energy of the optimised structures is higher or lower than the results I have obtained. Also, it could be seen whether the bond distances were closer to the literature values and whether the IR stretching frequencies follow the expected pattern. In this sense, it would be possible to work out to which extreme the alkenes in the complexes sit.

As an illustration, the molecular orbitals of the Pt(PPh3)2(C2H4) complex were calculated. DOI:10042/to-5911

The following results were obtained:

| File type | .fch |

| Calculation type | SP |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | GEN |

| Final energy (au) | -2270.79 |

| Final gradient (au) | 0.00 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 3.25 |

| Job time | 36 minutes 21 seconds |

Looking at the molecular orbitals, it can be seen that there is evidence of π back-bonding. The HOMO picture shows the C-C π* orbital mixing with platinum orbitals to form the molecular orbital. Other evidence of the bonding can be seen in pictures of the other molecular orbitals.

To conclude this research, it can be seen that the alkenes in my complexes do indeed bond to the platinum centre in a synergic fashion (as illustrated above). The extent of back-bonding can be seen to change depending on the R groups attached to the carbons. This is seen by the change in C-C bond length and stretching frequency. The calculations have managed to show this pattern to some success. I have also used molecular orbital calculations to illustrate the bonding mode. The differences in my results and the literature results does show that the alkenes do indeed interact with the platinum centre in a mix between the 2 extreme modes of bonding, and do not sit to either side of the bonding. The lowest energy minima may not have been found for the last 2 complexes. Perhaps better starting geometries, and more time available, will show that a starting geometry that was an accurate mix between the 2 extreme states (instead of more of a bias towards the metallacyclopropane arrangement) will give slightly lower minima. Also, higher basis sets could be used, but, this was not possible to experiment with as each job took around 20 hours to complete at the current level I have used.

Conclusion

It can be seen from this project, that computational chemistry can be used to model aspects of inorganic chemistry. It can be seen that the calculations are much quicker, easier and accurate for smaller molecules. Limitations to the calculations start to be shown when the calculations become more complicated for larger molecules containing a mix of different atoms. It can be seen that the basis sets used for my calculations may not have been accurate enough to model the structures- however the calculations I have completed took a long time to complete, and so larger basis sets would not have been possible to obtain results in the time given for this project. However, even relatively simple calculations still manage to show the correct pattern in results.

References

- ↑ The Ab Initio Limit Quartic Force Field of BH3: DOI:10.1002/jcc.20238

- ↑ On the Structures of the Hydrated Thallium(III) Ion and its Bromide Complexes in Aqueous Solution: DOI:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.36a-0125

- ↑ Synthesis of molybdenum complex with novel P(OH)3 ligand based on the one-pot reaction of Mo(CO)6with HP(O)(OEt)2 and water : DOI:10.1016/j.inoche.2004.09.012

- ↑ X-ray structural studies of cis-Mo(CO)4(PR3)2 (R = Me, Et, n-Bu) derivatives and their relationship to solution isomerization processes in these octahedral species: DOI:10.1021/ic00137a026

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Imperial College London- 2I3 Coordination and Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals, Lecture 7 "Transition Metal Alkyl and Carbene Complexes"

- ↑ More than Bystanders: The Effect of Olefins on Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions DOI:10.1002/anie.200700278