Rep:Mod2:nathanmarchMP

Mini-Project: Cubane and its tetrafluoro and tetraiodo derivatives: their stability and electronic character

Introduction and Aims

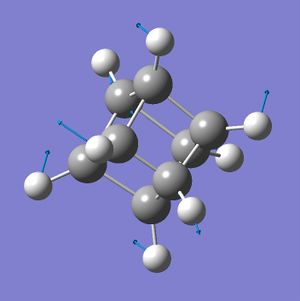

Cubane is hystorically interesting due to the once-prevalent belief that is was impossible to synthesize (first synthesized in 1964 by Philip E. Eaton[1]). It is chemically interesting due to the large degree of strain caused by the distorted sp3 geometry (90° rather than the typical 109.5°). While this distortion is thermodynamically disfavoured cubane is kinetically stable due to the lack of suitable decay pathways.

The analysis that will be carried out here will form three parts:

- The molecular orbitals, natural bond orbitals and vibrations of cubane will be examined. The aims here will be to:

- - shed light on the vulnerability of cubane to nucleophilic or electrophilic attack.

- - assess how the geometric distortion impacts on the hybridization of the carbon atoms.

- - characterize the vibrations.

- The molecular orbitals and charge densities of isomers of tetrafluorocubane will be examined. The aim here will be to decern how the electrophilicity of the non-fluorinated carbons will change as the configuration of the fluorines is changed.

- The molecular orbitals and charge densities of isomers of tetraiosocubant will be examined. The aims here will be to:

- - decern how the electrophilicity of the non-iodinated carbons will change as the configuration of the iodines is changed

- - compare the results with those of tetrafluorocubane, and make conclusions regarding how electronegative substituents affect the electrophilicity of cubane

Part 1.1: Building and Optimizing Cubane

Cubane was built via the template in ChemBio3D, and then edited in GaussView such that all C-C bonds measured 1.5727 Å and all C-H bonds measured 1.118 Å[2]. To optimize this structure a DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) optimization was run on this structure.

# opt b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity cubane optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [1]

- Results summary: Nm607_cubane_postopt_results_summary.txt

The post-optimization bond lengths were 1.570 Å and 1.092 Å for C-C and C-H respectively (to 3 d.p.). There was minor variation between the individual bonds lengths but the differences, though ruled out by symmetry, were ignored because of their size. Had the point group been forcibly applied before the optimization it might have unified the bond lengths. It is interesting to note that the C-C bond length is only a little above average (1.54 Å[3]); this could be a result of reduced hybridization energy required to make the carbons atoms sp3 hybridized (see Part 1.3). Less energy expended in hybridizing the parent orbitals will lead to an overall strengthening of the final bonds.

Part 1.2: Vibrational Analysis of Cubane

A combined frequency and NBO/MO analysis was executed on the optimized structure of cubane, a DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculation (additional keywords: pop=(full,nbo)).

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo) cubane frequency and NBO/MO analysis 0 1

- D-space reference: [2]

- Results summary: Nm607_cubane_postfreqNBOMO_results_summary.txt

The frequency analysis fully converged, and yielded the following IR spectrum:

This spectrum is close to the literature spectrum[1] where the only visible absorptions occured at 3000, 1231 and 851 cm-1. Each absorption is the result of a set of triply degenerate vibrations, that differ in energy by no more that one wavenumber. One can justify judging the orbital set as degenerate by looking at their shape - they are identical bar a rotation about some point.

As has been noted[4], the inaccuracy of computational methods with respect to vibrational energies is about 10%, thus it is no surprise to see that the absolute error between the computed and the practical vibrational energies increases as the energy increases. A difference of approximately 125 cm-1 between the predicted and practical highest-energy vibrations is still only a 4% error.

Part 1.3: NBOs of Cubane

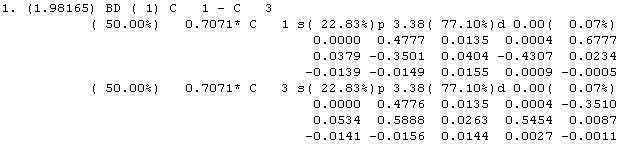

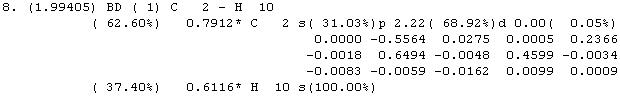

Cubane has sp3 carbons, with C-C-C angles of 90°. This distortion would require a reduced alteration of the p-orbitals to yield sp3 bonding orbitals. Analysis of the Natural Bond Orbitals shows an increased p-character:

NBO output:

sp3 hybridization should result in 75% p-character and 25% s-character. What is seen in the simulation of cubane is a slight increase in the p-character of the C-C bonds (77.10%), and a concomitant decrease in p-character of the C-H bonds (68.92%). It is easy to see how the p-orbitals, directed as they are along the C-C bonds naturally would be reluctant to deform to bond with the hydrogen atom; thus the s-orbital, which has made a weaker contribution to the C-C bonds, makes up the difference.

Part 1.4: Charge Distribution of Cubane

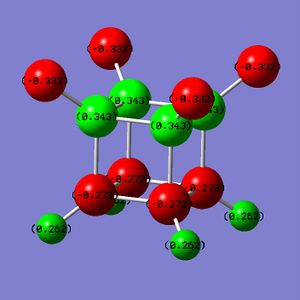

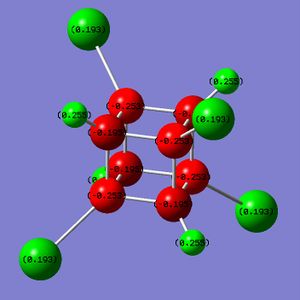

Simply on the basis of electronegativity one would expect the carbon atoms to be electron-rich (Χ(C) = 2.55; Χ(H)= 2.20[5]) - this is indeed the case. The precise distribution is displayed in Fig. 3.1.4.1. What can be inferred from this distribution is that the carbons in cubane should be vulnerable to electrophilic attack, and resistant to nucleophilic attack. Whether or not cubane is reactive in reality will be influenced by the charges, but will depend mostly on the presense of orbitals of suitable symmetry and energy that are able to interact with suitable orbitals on the electrophile (or nucleophile).

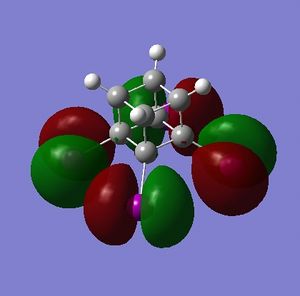

Part 1.5: MOs of Cubane

NOTE: Any discussion of nucleophilicity or electrophilicity is with the understanding that cubane is a non-functionalized hydrocarbon and is therefore neither strongly nucleophilic or strongly electrophilic.

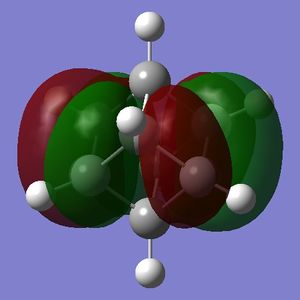

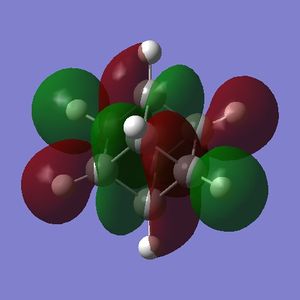

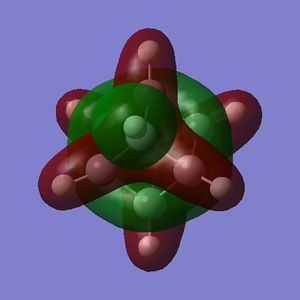

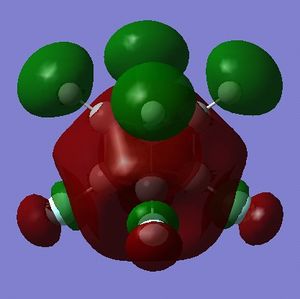

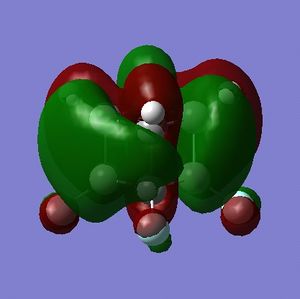

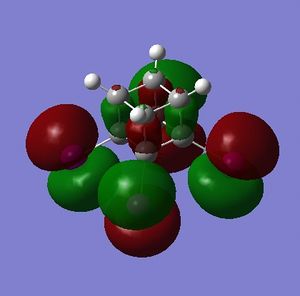

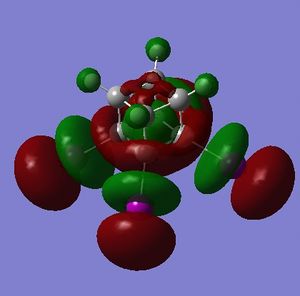

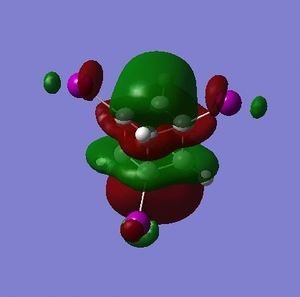

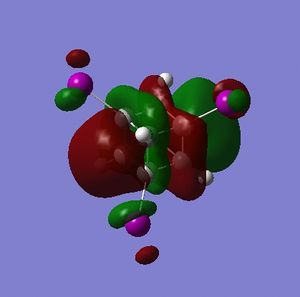

The HOMO and LUMO are of prime interest here, but additional molecular orbitals are shown below.

What can be seen from the MOs of cubane is that:

- the HOMOs (0,+1,+2) and LUMOs (0,-1,-2) are largely p-orbital based, having nodes through all eight carbon atoms.

- the HOMO, HOMO-1 and HOMO-2 and the LUMO, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 are triply degenerate symmetry-related orbitals.

- the HOMO has plenty of electron density present on carbons; this indicates that these carbon atoms are able to act as nucleophiles, donating electron density into the LUMO of an electrophile.

- the LUMO has large lobes either side of the carbon atoms that indicates that they are available for receiving electron density; the kinetics of any reaction would require that the electrostatic repulsion between the carbon and any attacking nucleophile be overcome. While the shape of the MO seems to indicate that nucleophilic attack is possible, in practice this may not occur due to incorrect symmetry, poor MO energy compatability or any number of kinetic considerations.

Part 2: Tetrafluorocubane

Substituting four of the eight hydrogens on cubane with fluorine atoms should withdraw electron density from the carbon structure, making certain carbon atoms more susceptible to nucelophilic attack. However fluorine is a poor leaving group so the atoms of interest will be the non-fluorinated carbons, as these could be substituted with good leaving groups for nucleophilic attack.

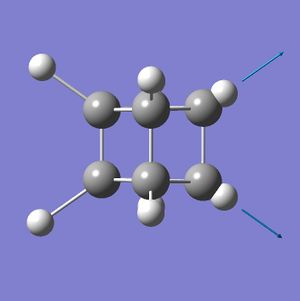

It was thought that four fluorine atoms would be appropriate so that the greatest degree of symmetry would be maintained, making analysis easier. The two configurations chosen were tetrafluorocubane with all fluorines on one face (A), and tetrafluorocubane where no fluorines are on adjacent carbons (B).

Both A and B should have sufficient symmetry to induce only two classes of carbon atoms, those with and those without flourine. Thus the analysis simplified is simplified. A has C4v{E,2C4(z),C2,2σv,2σd} symmetry, while B has Td{E,8C3,3C2,6S4,6σd} symmetry. Cubne on the other hand has Oh{E,8C3,6C2,6C4,3C2,i,6S4,8S6,3σh,6σd} symmetry. These differences, particularly the C3 vs. C4 symmetry, should be visible in the shape of the MOs. The Td point group has more in common with the Oh than does C4v so it is conceivable that the molecular orbitals of B will have more morphological similarity with those of cubane than will A.

Part 2.1: Building and Optimizing A and B

Using the cubane files as a template, the particular positions were fluorinated and the structures optimized via DFT-B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations.

The code for the optimization of A:

# opt b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity faceFcubane optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [3]

- Results summary: Nm607_faceFcubane_postopt_results_summary.txt

The code for the optimization of B:

# opt b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity vertexFcubane optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [4]

- Results summary: Nm607_vertexFcubane_postopt_results_summary.txt

Subsequent frequency analysis of both converged: DFT-B3LYP/6-31G (additional keywords: pop=(full,nbo)).

The code for the frequency analysis of A:

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo) faceFcubane frequency/NBO/MO analysis 0 1

- D-space reference: [5]

- Results summary: Nm607_faceFcubane_postfreqNBOMO_results_summary.txt

The code for the frequency analysis of B:

# freq b3lyp/6-31g(d) geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo) vertexFcubane frequency/NBO/MO analysis 0 1

- D-space reference: [6]

- Results summary: Nm607_vertexFcubane_postfreqNBOMO_results_summary.txt

Part 2.2: Charge Distribution of A and B

The NBO charge distributions for A and B show that addition of fluorine does result in carbon atoms with one of two charges, but the charge distribution is such that those carbon atoms that are not bound to flourine atoms are more nucleophilic (more negatively charged) than in cubane.

Thus, rather than acting as electron sinks as hoped, the flourine atoms act as strong polarizing agents, taking electron density from the carbon they are immediately bound to but causing adjacent carbon atoms to accumulate charge. Interestingly B has more electron-rich and more electron-poor carbons than A - obviously distributing the flourine atoms around the carbon skeleton reduces the redundancy of each.

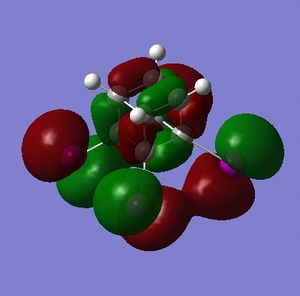

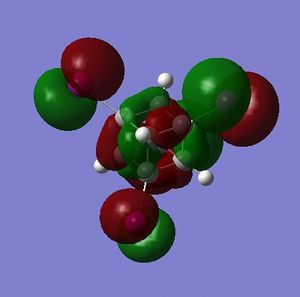

Part 2.3: MOs of A and B

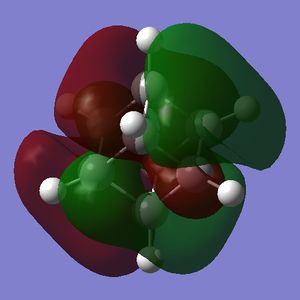

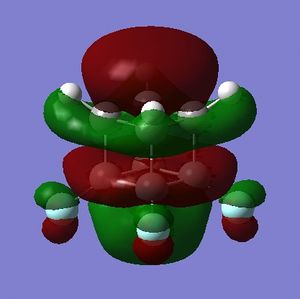

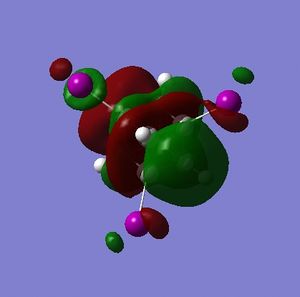

For both A and B the orbitals do not precisely resemble those of cubane. There are a few exceptions, and the symmetry has mostly been retained but the relative energies have changed in some cases.

To start with, for A, the HOMO-3 best resembles the HOMO-3 of cubane but has C2 rather than C3 symmetry; the HOMO-2 and HOMO-1 resemble those of cubane only in that they are a doubly degenerate set, there is little visually that compares. The HOMO and LUMO of A would compare well with those of cubane if they were swapped i.e. the HOMO of A were the LUMO and visa-versa. The symmetry and node-character of the HOMO of A resembles more the LUMO of cubane and visa-versa. This could be important for certain reactions where, say, the LUMO of an electrophile has the wrong symmetry to interact with the HOMO of cubane - by adding flourine substituents the symmetry of the HOMO could be adjusted and the reaction might work.

The LUMO A is closest is form to the LUMO+3 of cubane, and addition of flourine distrupts the degeneracy of the LUMO, LUMO+1 and LUMO+2 of cubane.

B, as predicted, has molecular orbitals that more closely resemble those of cubane than those of A, though, like A, the LUMO of B does resemble the LUMO+3 of cubane.

What is important about the HOMOs and LUMOs of A and B is that the presense of fluorines has shifted electron density onto the non-fluorinated carbon atoms. A visual assessment of the relative size of the lobes about carbon atoms in the HOMO and LUMO of A vs. cubane indicates that:

- A is less nucleophilic than cubane at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is less nucleophilic at the fluorinated carbons (made by examining the size of the HOMO on the relevant carbon atom - larger lobe, more nucleophilic)

- A is less electrophilic than cubane at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is more electrophilic at the fluorinated carbons

A visual assessment of the relative size of the lobes about carbon atoms in the HOMO and LUMO of B vs. cubane indicates that:

- B is less nucleophilic than cubane at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is less nucleophilic at the fluorinated carbons

- B is less electrophilic than cubane at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is more electrophilic at the fluorinated carbons

Likewise for A and B:

- A is about as nucleophilic as B at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is more nucleophilic at the fluorinated carbons

- A is about as electrophilic as B at the non-fluorinated carbons, and is about as electrophilic at the fluorinated carbons

Part 3: Tetraiodocubane

One would expect tetraiodocubane to have similar electronic character to tetrafluorocubane. What is synthetically different about tetraiodocubane is that iodine is a good leaving group. If the same charge distribution is present in tetraiodocubane as in tetrafluorocubane then tetraiodocubane should be vulnerable to nucleophilic substitution at the iodo-substituted centres.

The two structures examined in this section are identical to those in Fig. 3.2.0.1, save for the presence of iodine rather than fluorine atoms. The two structures are therefore and .

Part 3.1: Building and Optimizing C and D

The basis set used to model tetrafluorocubane cannot be applied to tetraiodocubane because of the complexity of iodine. Tetrafluorocubane has only 88 electrons, while tetraiodocubane has a massive 264. Without a pseudo-potential to model the many core electrons of the heavy iodine atoms the calculation would be very many times more difficult. What was used instead of 6-31G was LanL2MB (first, to produce a sensible structure) followed by LanL2DZ (a higher level basis set, a so-called 'Double Zeta' function, that would perfect the output of the LanL2MB optimization.

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2MB geometry optimization of C (additional keywords: opt=loose):

# opt=loose b3lyp/lanl2mb geom=connectivity faceIcubane 1st optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [7]

- Results summary: Nm607_faceIcubane_postopt_results_summary.txt

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2MB geometry optimization of D (additional keywords: opt=loose):

# opt=loose b3lyp/lanl2mb geom=connectivity vertexIcubane 1st optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [8]

- Results summary: Nm607_vertexIcubane_postopt_results_summary.txt

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2DZ geometry optimization of C:

# opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity faceIcubane 2nd optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [9]

- Results summary: Nm607_faceIcubane_post2opt_results_summary.txt

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2DZ geometry optimization of D:

# opt b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity vertexIcubane 2nd optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [10]

- Results summary: Nm607_vertexIcubane_post2opt_results_summary.txt

The optimized structures were then subjected to a DFT-B3LYP/LanL2DZ frequency analysis (additional keywords: pop=(full,nbo)), both of which converged.

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2DZ frequency analysis of C:

# freq b3lyp/lanl2dz geom=connectivity pop=(full,nbo) faceIcubane 2nd optimization 0 1

- D-space reference: [11]

- Results summary: Nm607_faceIcubane_postfreqNBOMO_results_summary.txt

The code for the DFT-B3LYP/LanL2DZ frequency analysis of D:

- D-space reference: [12]

- Results summary: Nm607_vertexIcubane_freqNBOMO_results_summary.txt

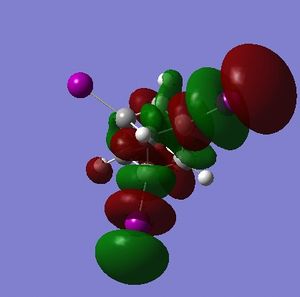

Part 3.2: Charge Distribution of C and D

What is interesting about the charge distribution of C (Fig. 3.3.2.1) is that the charge of the iodine-bound carbons is exactly that of the carbon atoms in cubane. Those not directly bound to iodine atoms have a reduced negative charge, making these centres more electrophilic than for cubane (but by only a small amount). In comparison to A, C shows very different character in that the halide-bound carbons are still negatively charged; iodine has only a slightly high electronegativity than carbon (Х(I) = 2.66[5]) so one would expect a less extreme difference when compared to fluorine (Χ(F) = 3.98[5]).

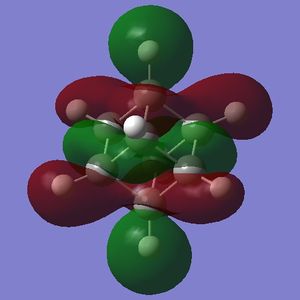

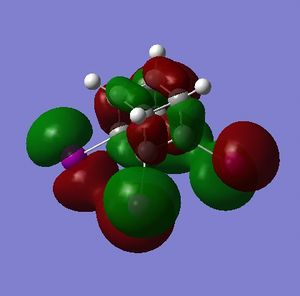

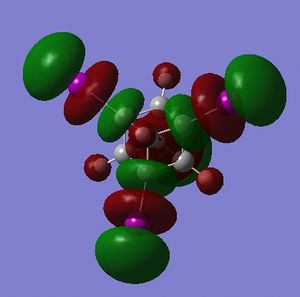

Part 3.3: MOs of C and D

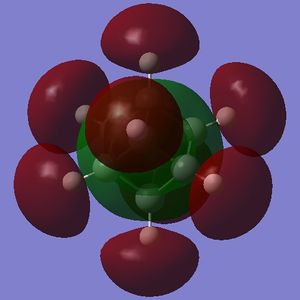

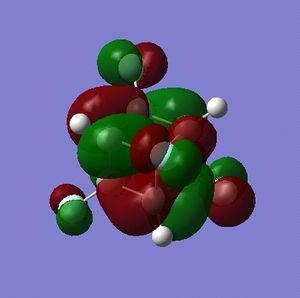

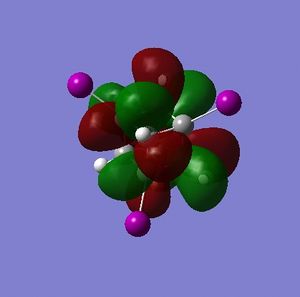

Additional LUMOs are displayed for the tetraiodocubane species because of the presense of unoccupied bonding orbitals. This is a huge indication that tetraiodocubane is susceptibile to nucleophilic attack, and electron donation. An electron-rich, electron-donating nucelophile can attack tetraiodocubane, evict an iodine anion and stabilize the molecule.

For C the electron density of HOMO is nearly completely on the iodine atoms, meaning that the carbon atoms are very poor nucleophiles. This is slightly less so in D, but there is still little electron density on the carbon atoms compared with the HOMO of cubane.

The LUMO, on the other hand, for both C and D has plenty of electron density on the iodinated carbon atoms, and very little or none on the non-iodinated carbon atoms. Thus the reactive centres in the tetraiodocubanes are the iodinated carbons - they are vulnerable to nucleophilic eliminations, at least theoretically. SN2 reactions are obviously disallowed by the nature of the cubane skeleton but SN1 is only slightly more plausible because of the geometry which will not distort to the sp2 planar geometry required of a stable carbocation. For the sake of argument however, let us examine the stability of the intermediate carbocation. In C the carbocation resulting from elimination of any single iodine will be stabilized by σ-conjugation via 2 × C-I σ-orbitals and 1 × C-H σ-orbital; in D the equivalent carbocation would be stabilized by σ-conjugation via 3 × C-H σ-orbitals. The adjacent iodine atoms should be more stabilizing due to donation of their lone pairs, so in theory C will be more reactive but the whole question is acedemic.

Part 4: Comparisons

Part 4.1:Charge Distribution

| Table 3.4.1.1 - NBO Charges of atoms on studied molecules | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom | Cubane | Tetrafluorocubane | Tetraiodocubane | ||

| A | B | C | D | ||

| C-H | -0.239 | -0.273 | -0.355 | -0.192 | -0.195 |

| C-H | 0.239 | 0.262 | 0.272 | 0.239 | 0.255 |

| C-X | - | 0.343 | 0.422 | -0.273 | -0.253 |

| C-X | - | -0.332 | -0.340 | 0.227 | 0.193 |

Part 4.2: Energies

| Table 3.4.2.1 - Energies and relative energies of cubane and its derivatives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Energy / Eh | Energy / kJ mol-1 | Relative Energy / kJ mol-1 |

| Cubane | -309.4603926 | -812488.26 | |

| A | -706.3840440 | -1854611.31 | 29.14 |

| B | -706.3951434 | -1854640.45 | 0.00 |

| 'C' and 'D' were computed using a different basis set, therefore their energies are incompatible with those of 'A' and 'B' | |||

| C | -352.5282262 | -925562.86 | 10.62 |

| D | -352.5322696 | -925573.47 | 0.00 |

The tetrahalocubanes with the halogens distributed over the carbon skeleton (B and D) are more stable than those with all four halogens on one face (A and C). This is due to the repulsive interactions between halogens when they are adjacent carbons. As can be seen from Table 3.4.2.1, the difference energy between the two isomers is less when the halogen is iodine because, despite iodine being a larger atom, the C-I bonds are longer than the C-F bonds - the iodine atoms are further from their neighbours than fluorines would be in the same positions.

Evaluation

What has been shown by the analysis above is that the reactivity of cubane is not significantly altered by the addition of halide substituents. While the charges, and the shape and character of the molecular orbitals is altered significantly the inherent poor reactivity of cubane. The inviability of both SN1 and SN2 reaction mechanisms and the lack of any major change in reactivity of non-substituted carbons on the cubane derivatives would seem to rule out halocubanes as good synthetic intermediates. The literature begs to differ however, with oxidative nucleophilic displacement[6], alkylation[7] and sulphur functionalizations[8].

The basis set used, 6-31G, was a high level one but most calcalations were completed within minutes. It might have been worth using an even higher basis set. On the other hand, the results are sensible and a higher basis set could be considered a waste of resources.

The results appeared sound, and examining the molecular orbitals and their impact on reactivity was interesting. What would be more interesting would be examining the decomposition pathways that must exist for cubane and methods to encourage or discourage them (though the later hardly seems necessary.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 P. E. Eaton, T. W. Cole, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1964, 86, 3157-3158. DOI:10.1021/ja01069a041

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/local/projects/b_muir/Cubane/Cubanepro/Start.html

- ↑ J. C. Kotz, P. Treichel, Chemistry & Chemical Reactivity, Volume 2, 2008, 7th Edition, 387. ISBN 978-0-495-38713-8

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/hunt/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/8a_accuracy.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 A. L. Allred, J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem., 1961, 17, 215-221. DOI:10.1016/0022-1902(61)80142-5

- ↑ R. M. Moriarty, S. M. Tuladhar, R. Penmasta, A. K. Awasthi, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1990, 112, 3228–3230. DOI:10.1021/ja00164a063

- ↑ P. E. Eaton, M. Maggini, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1988, 110, 7230–7232. DOI:10.1021/ja00229a057

- ↑ R. Priefer, Y. J. Lee, F. Barrios, J. H. Wosnick, A. Lebuis, P. G. Farrell, D. N. Harpp, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2002, 124, 5626–5627. DOI:10.1021/ja025823y