Rep:Mod2:man7286

Introduction

This lab uses computational techniques to calculate various properties of small inorganic molecules, ranging from bond lengths and angles to IR spectra and molecular orbitals. The structures of the molecules were drawn using Gaussview5 or ChemBio3D Ultra. Calculations were performed by Gaussian and the results analysed through Gaussview5.

BH3

Geometry Optimisation[1]

The method and basis set used for the geometry optimisation of BH3 were B3LYP/3-21G, this is a relatively low accuracy basis set. The optimised bond length was 1.19 Å and the bond angle was 120.0°. Both these parameters agree exactly with the literature[2]. Figure 1 shows the summary of results from the calculation, the optimised energy for the molecule is -26.46 Eh.

.

Molecular Orbital Analysis[3]

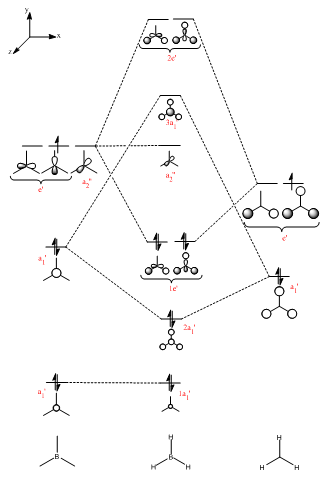

The shape of the orbitals in the MO diagram for BH3 were predicted using LCAO theory and the relative energy levels were estimated.

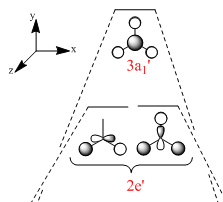

Figure 2 shows the predicted MO diagram for BH3. Table 1 shows the calculated MOs for the molecule. The calculated MOs were tabulated in ascending order of energy and the corresponding LCAO was matched to it. Most of the calculated LCAOs are in the same order as on the MO diagram. The only exception is that the 3a1' orbital was calculated to be higher in energy than the 2e' degenerate pair, whereas I predicted it to be lower in energy. The correction to the diagram is shown in Figure 3. The shape of the calculated MOs match up well to the predicted LCAOs, showing that qiualitative MO theory can be very useful in predicting the shape of the molecular orbitals.

Natural Bond Orbital Analysis[3]

NBO Charges: B = 0.33, H = -0.11

Figure 4 shows the charge distribution and NBO charges for the BH3 molecule. The light green colour of the boron atom shows that it is strongly positively charged. This is to be expected as boron has an empty p orbital, making it a Lewis acid.

NBO analysis is also used to determine the nature of the bonding in the molecule. Figure 5 shows that there are three sp2 bonds, each containing two electrons, and one lone pair with mainly s charachter, also containing two electrons. It also shows that slightly more of the electron density of the bonds lies on the hydrogen atom, which further explains the positive charge on the boron atom.

Frequency Analysis[4]

Table 2 shows the six vibrations of the planar BH3 molecule, but the IR spectrum in Figure 5 only shows three peaks. This can be explained by the data in the table. Vibration 4 is the in-plane symmetric stretch of the 3 B-H bonds, therefore the overall dipole of the molecule doesn't change so the intensity of the vibration is 0. Vibrations 2 & 3 and 5 & 6 are degenerate pairs so the two vibrations form a single peak.

TlBr3

Geometry Optimisation[5]

The method and basis set used was B3LYP/LanL2DZ, which is a medium accuracy basis set. The optimised bond length was 2.65 Å and the Br-Tl-Br angle was 120.0°. The literature bond length is 2.56 Å[6] therefore the difference between experimental and calculated is 0.09 Å. The calculation is therefore in good agreement with the literature.

Frequency Analysis

The same method and basis set must be used for the original optimisation and the frequency calculation so that both calculations are at the same level of accuracy. Frequency analysis must be carried out because the optimisation is based of the first derivative of the potential energy curve, therefore it only picks a point where the gradient is zero i.e. the graph is at a maximum or minimum. Frequency analysis performs a second derivative on the potential energy curve. The analysis is performed on the optimised file therefore where the gradient is zero. If the second derivative is positive this point is a minimum and if negative the point is a maximum. The frequency analysis is therefore carried out to ensure that the optimised geometry is at the energy minimum.

| Low Frequencies | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -3.4226 | -0.0026 | -0.0004 | 0.0015 | 3.9361 | 3.9361 |

| 46.4288 | 46.4291 | 52.1449 | |||

The first row of low frequencies represent the motions of the centre of mass of the molecule. Essentially they form the "-6" term in the 3N-6 equation, which determines the number of vibrational modes in a non-linear molecule where N is the number of atoms. Ideally these should all be zero, but due to experiment error they normally lie within ±10 cm-1. The frequencies in the second row represent the vibrational frequencies of the molecule and must all be positive. The fact that these all are means that the calculation has found the correct minimum energy.

| Frequency | Intensity | Point Group |

|---|---|---|

| 46 | 4 | e' |

| 46 | 4 | |

| 52 | 6 | a2" |

| 165 | 0 | a1' |

| 211 | 25 | e' |

| 211 | 25 |

Lit. stretches are 257, 220 cm-1[7].

Again, there are six vibrational modes for TlBr3 but only three peaks on the IR spectrum, Figure 7. One vibration is not IR active and there are two degenerate pairs. The frequencies are much lower for TlBr3 than BH3. This is because the bonds are longer and therefore weaker. Also, the e' vibration is lower in energy than a2" whereas in BH3 it is higher in energy.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

The method and basis set used for the following optimisation and frequency calculations was B3LYP/LANL2MB.

In this exercise the optimised geometries and IR spectra for cis- and trans- isomers of Mo(CO)4L2 were calculated and compared. The main focus was the number and frequency of carbonyl stretches. The length of the C-O bond in cabon monoxide is 1.128 Å and the stretching frequency is 2143 cm-1[8]. There are two types of bonding between the CO ligand and a metal: σ-donation and π-back bonding.

In σ-donation electrons are donated from the carbon p orbital to a relavant orbital on the metal. In π-back bonding electrons are donated from a d orbital on the metal to the π* orbital on the carbon. Donation into this orbital weakens the CO bond and therefore lowers the carbonyl stretching frequency.

cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Geometry Optimisation[9]

energy = -617.52 Eh

| Bond | Length/Å | Literature Value/Å | Bond | Angle/° | Literature Value/° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-C (axial) | 2.11 | 2.041 | C-Mo-C (axial) | 177.9 | 174.1 |

| Mo-C (equatorial) | 2.06 | 1.972 | C-Mo-C (equatorial) | 89.0 | 83.0 |

| Mo-P | 2.53 | 2.577 | P-Mo-P | 93.0 | 104.62 |

| C-Mo-P (axial) | 177.3 | 163.7 | |||

| C-Mo-P (equatorial) | 89.7 | 80.6 |

The values are all close to the literature values, within experimental error (~10%).

Frequency Calculation[11]

energy = -617.52465357 Eh

The literature CO stretches for cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 are 2070 and 1987 cm-1[12]. The calculated values are within experimental error but there are three carbonyl peaks on the predicted spectrum and only two in the literature.

trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Geometry Optimisation[13]

energy = -617.52

| Bond | Length/Å | Literature Value | Bond | Angle/° | Literature Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mo-C | 2.11 | 2.011 | C-Mo-C (trans) | 179.7 | 180.0 |

| C=O | 1.19 | 1.165 | C-Mo-C (cis) | 90.0 | 92.1 |

| Mo-P | 2.48 | 2.500 | P-Mo-P | 179.0 | 180.0 |

| C-Mo-P | 90.0 | 89.6 |

Frequency Calculation[15]

energy = -617.52206254 a.u.

low frequencies: -0.0002 0.0005 0.0006 4.2294 4.7994 8.7431 9.3212 14.1821 29.9911

lit. IR 1953, 1896cm-1[16]

Conclusion

NOTE: In the gaussian files produced from the calculations there were no bonds present between the P and Cl atoms. This is because the optimised bond length is longer than most organic bond lengths so the gaussian program doesn't put a bond between the atoms. When converting to .mol files on ChemBio3D Ultra I added bonds between the P and Cl atoms, this did not affect the geometry of the molecule.

The axial Mo-C bonds on the cis isomer and all the Mo-C bonds on the trans isomer were calculated to be the same length, the equatorial bonds are 0.05 Å shorter. This is because they are trans to the PCl3 group therefore the metal is donating less of its electron density to the phosphorus atom, meaning there is more being donated to the carbon atom so the bond is shorter. The donation of electrons from the metal to the carbon goes into the π* orbital of the C-O bond, therefore weakening the C-O bond. This explains why the equatorial C-O stretches have a slightly lower frequency than the axial/trans isomer stretches.

IR spectroscopy is a good way to distinguish between the two isomers as the cis isomer has four IR active carbonyl stretches and the trans isomer only has two. This is because two of the carbonyl stretches in the trans isomer are symmetric so the overall dipole moment of the molecule doesn't change, i.e. they are not IR active. The trans isomer also has fewer peaks in the IR spectrum because it has a higher order of symmetry than the cis isomer, therefore more trans stretches are symmetrical and therefore IR inactive.

The cis isomer is more stable as it is lower in energy by 0.002591 Eh, 6.8 kJ mol-1. This energy difference is very small, it is the same order of magnitude as the energy available at room temperature, therefore the two isomers will rapidly interconvert at room temperature.

Mini Project: Al2Cl6

The method and basis set used for all optimisation and frequency calculations was B3LYP/6-31G.

Al2Cl6

Optimisation

energy = -3246.320 Eh

Frequency

Al2Cl6 Frequency Calculation Log File

low frequencies: -5.8229 -5.6361 -0.0035 -0.0025 0.0028 2.6199 21.6041 51.6546 85.1422

| Frequency | Intensity | Vibration Type |

|---|---|---|

| 22 | 0 | Bridging Al-Cl-Al bonds bend out of plane, exterior Cl-Al-Cl groups rock symmetrically in plane, Al stationary |

| 51 | 0 | Exterior Cl-Al-Cls twist asymmetrically out of plane |

| 85 | 0 | Exterior Cl-Al-Cls bend symmetrically in plane |

| 99 | 0 | Bridging Cls move asymmetrically out of plane |

| 102 | 0 | Exterior Cl-Al-Cls rock in plane, Als move |

| 113 | 14 | Al2Cl2 square moves up and down in plane, exterior Cls move down and up |

| 124 | 25 | Exterior Cl-Al-Cls bend asymmetrically in plane |

| 145 | 0 | Al2Cl2 square twists in plane |

| 159 | 18 | Bridging Al-Cl-Al bonds bend out of plane, exterior Cl-Al-Cl groups rock symmetrically in plane, Als move |

| 199 | 0 | Bridging Al-Cl-Al bonds bend in plane, exterior Cl-Al-Cl groups bend symmetrically in plane |

| 222 | 0 | Bridging Al-Cl-Al bonds bend asymmetrically, oppositely, in plane |

| 277 | 103 | Bridging Al-Cl-Al bonds bend asymmetrically, together, in plane |

| 294 | 0 | Bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically |

| 355 | 153 | Bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on same side, asymmetrically to opposite side |

| 437 | 365 | Exterior Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on same side, asymmetrically to opposite side |

| 476 | 0 | Exterior Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on both sides |

| 570 | 0 | Exterior Al-Cl bonds stretch asymmetrically on same side, asymmetrically to opposite side |

| 580 | 258 | Exterior Al-Cl bonds stretch asymmetrically on same side, symmetrically to opposite side |

MO and NBO Analysis

MO/NBO log file[17]

Al2Cl4Br2

| Al2Cl6 | Al2Cl4Br2 Bridging | Al2Cl4Br2 Geminal | Al2Cl4Br2 Cis | Al2Cl4Br2 Trans | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Difference from lowest energy isomer/kJ mol-1 | n/a | 0.244 | 0.460 | 0 | 0.165 | |

| Bond Lengths/Å | exo Al-Cl | 2.17 | 2.18 | 2.17 | 2.17 | 2.17 |

| bridging Al-Cl | 2.41 | n/a | 2.40,2.42 | 2.41 | 2.41 | |

| exo Al-Br | n/a | n/a | 2.29 | 2.29 | 2.29 | |

| bridging Al-Br | n/a | 2.52 | n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| Bond Angles/° | Bridge | 93.6 | 89.6 | 92.8 | 92.5 | 92.7 |

| exo Cl-Al-Cl | 123.3 | 123.0 | 122.5 | n/a | n/a | |

| exo Br-Al-Cl/Br | n/a | n/a | 129.0 | 125.7 | 125.7 | |

Bridging Optimisation log file

Bridging Frequency calculation log file

Bridging MO/NBO log file[18]

Geminal Frequency calculation log file

Geminal MO/NBO log file[19]

Cis Frequency calculation log file low frequencies: -5.5122 -5.1026 -3.2210 -0.0105 -0.0057 -0.0057 13.1103 48.2344 72.1486

| Frequency | Intensity | Stretch |

|---|---|---|

| 279 | 0 | Bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically |

| 352 | 136 | Bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on both sides |

| 397 | 369 | Exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch symmetrically on one side, asymmetrically to the other side |

| 442 | 19 | Exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch symmetrically on both sides |

| 551 | 21 | Exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch asymmetrically on one side, asymmetrically to the other side |

| 562 | 232 | Exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch asymmetrically on one side, symmetrically to the other side |

Cis MO/NBO log file[20]

Trans Optimisation log file[21]

Trans Frequency calculation log file

| Frequency | Intensity | Stretch |

|---|---|---|

| 278 | 0 | bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on one side, symmetrically to other side |

| 353 | 136 | bridging Al-Cl bonds stretch symmetrically on one side, asymmetrically to other side |

| 400 | 396 | exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch symmetrically on one side, asymmetrically to other side |

| 441 | 0 | exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch symmetrically on one side, symmetrically to other side |

| 552 | 0 | exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch asymmetrically on one side, asymmetrically to other side |

| 561 | 249 | exterior Al-Cl/Al-Br bonds stretch asymmetrically on one side, symmetrically to other side |

Trans MO/NBO log file[22]

Conculsion

The cis isomer is the lowest energy, most stable, isomer but the difference in energy between this isomer and the rest is very small so interconversion between the isomers occurs readily at room temperature. The interconversion happens because one of the bridging bonds breaks, the other bridging bond rotates and a new bridging bond forms between the new atom.

In general the Al-Br bond is longer than the Al-Cl bond by 0.12 Å, this is because the orbital overlap is weaker therefore the bond is weaker. Also, the bridging Al-X bonds are longer than the exo Al-X bonds (X=Cl,Br). This is because the bridging bonds are 3 centre-4 electron bonds.

Bridging Br atoms increase the length of the exo Al-Cl bond by 0.01 Å. Geminal Br atoms lengthen the bridging Al-Cl bond on that side by 0.01 Å, but shorten it by the same amount on the other side, therefore on average the bond length remains the same. Cis and trans Br atoms have no effect on the bridging or exo Al-Cl bond length. The bridging angle is decreased most by bridging Br atoms, by 4°. Cis Br atoms decrease the angle by 1.1°, trans by 0.9° and geminal by 0.8°. Bridging Br atoms don't affect the exo angle. Geminal Br atoms decrease the exo Cl-Al-Cl angle by 0.8° and increase the Br-Al-Br by 5.7°. Cis and trans Br atoms increase the exo angle by 2.4°.

The addition of cis and trans Br atoms decreases the stretching frequencies of the Al-Cl and Al-Br bonds. This is because the Al-Br bonds are weaker so in general have lower stretching frequencies.

The shown occupied MOs (HOMO to HOMO-5) all show that the electron density is on the chlorine atoms. Therefore they are electron rich and the aluminium atoms are electron deficient.

References

- ↑ BH3 Optimisation Log File

- ↑ K. Kawaguchi, J. Chem. Phys., 1992, 96, 3411 DOI:10.1063/1.461942

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 MO and NBO Calculation Published Data DOI:10042/to-7497

- ↑ BH3 Frequency Calculation Log File

- ↑ TlBr3 Optimisation Log File

- ↑ J. Glaser, G. Johansson, Acta Chem. Scand., 1982, A 36(2), 125 DOI:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.36a-0125

- ↑ J. Blixt, J. Glaser, J. Mink, I. Persson, P. Persson, M. Sandstroem, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117 (18), 5089 DOI:10.1021/ja00123a011

- ↑ http://www.ilpi.com/organomet/carbonyl.html accessed 15:29 15/0./2011

- ↑ Geometry Optimisation Published Data DOI:10042/to-7571

- ↑ F.A. Cotton, D.J. Darensbourg, S. Klein, B.W.S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21 (1), 294, DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ Frequency Calculation Published Data DOI:10042/to-7576

- ↑ S.L. Mukerjee, S.P. Nolan, C.D. Hoff, R. Lopez de la Vega, Inorg. Chem., 1988, 27 (1), 81 DOI:10.1021/ic00274a018

- ↑ Geometry Optimisation Published Data DOI:10042/to-7572

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254 (1), 167 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ Frequency Calculation Published Data DOI:10042/to-7577

- ↑ M. Ardon, G. Hogarth, D.T.W. Oscroft, J. Organ. Chem., 2004, 689 (15), 2429 DOI:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2004.04.030

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7692

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7693

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7694

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7695

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7666

- ↑ Published Data DOI:10042/to-7696