Rep:Mod2:kc8

Module 2

Borane, BH3

Optimising a Molecule of BH3

The optimisation of borane (BH3) would be carried out using quantum mechanical methods using Gaussian and the structure and bonding of the molecule would be investigated.

Firstly, each of the three B-H bond lengths was increased to 1.5 Å. The optimisation was then carried out. The optimisation is carried out using two processes.

- SCF: The positions of the nuclei are fixed and the Schrödinger equation is solved for the electron density and the energy.

- OPT: The positions of the nuclei are moved (ie different geometries) and the SCF cycle repeated at each geometry to find the one of lowest energy.

The optimisation of BH3 was carried out using the following parameters.

- Method: B3LYP

- Basis Set: 3-21G

- Type of calculation: OPT (optimisation)

The method B3LYP (Becke 3-Parameter, Lee-Yang-Par) determines the type of approximations that are made in solving the Schrödinger equation. B3LYP is a hybrid exchange correlation functional, a type of approximation to the exchange-correlation energy function in density functional theory (DFT). The basis set is the set of functions used to construct the molecular orbitals, which are expanded as a linear combination of these functions, where the coefficient of each function is to be determined. The basis set used in this exercise, 3-21G, is a relatively simple and inaccurate basis-set and as such, it will be quick to optimise with. After the optimisation had been run, two output files were created, a .chk file and a .log file. The .log file was viewed in WordPad to confirm that the job had converged. A shortened version of the Gaussian calculation summary is shown in the table below.

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

|---|---|

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -26.462 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00021 a.u. |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Job cpu time | 16.0 seconds |

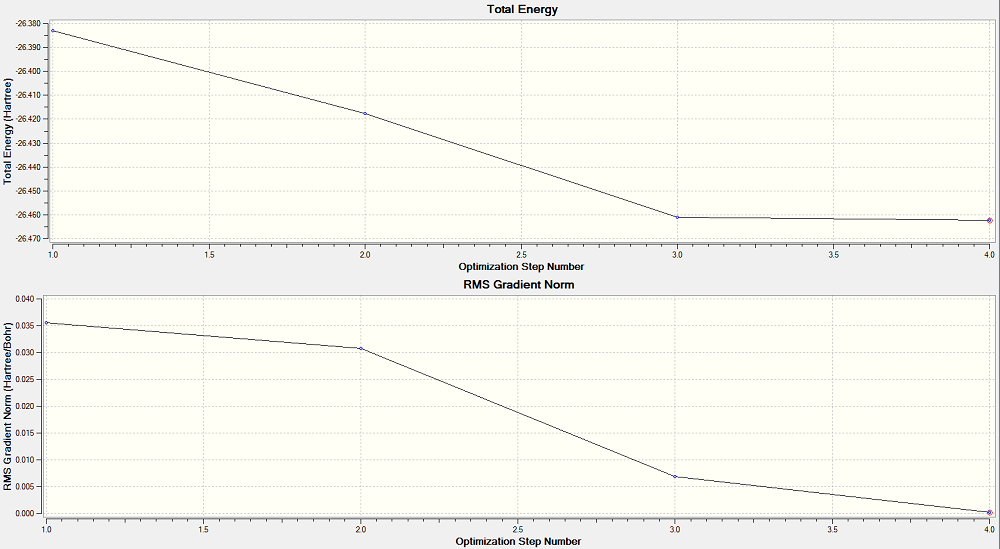

The .log file was opened with the "Read Intermediate Geometries" tick-box checked. This allows the Optimisation plot to be viewed. The first graph gives the total energy against the optimisation step number (this should converge to a minimum) and the second graph gives the RMS gradient against the optimisation step number (this should converge to zero, a turning point).

The structure of borane was seen through the different steps of the optimisation process. In the first and second steps of the optimisation, no bonds were seen between the atoms. This is because GaussView assigns bonds using a distance criteria between atoms. This is the simplest and fastest method of assigning bonds, although a more accurate method would be to measure the electron density between the atoms and assign bonds on that basis. The idea of a bond between atoms is in itself a simplification of the actual structure of a molecule and so using simple distance criteria to assign the presence of bonds is sufficient.

The potential energy curve for a diatomic against R, the distance between two nuclei, can be approximated by the Lennard-Jones curve. The minimum point in the curve represents the equilibrium distance. Since the potential energy and force are related by:

,

we can see that the force acts as a restoring force, acting in the opposite direction of the displacement from the equilibrium position. Therefore, in order to find the equilibrium position, the first derivative of the energy with respect to the internuclear separation is calculated and the separation changed in the inverse "direction" and the procedure is repeated until a value for R is found where the gradient is equal to zero.

Molecular Orbitals of BH3

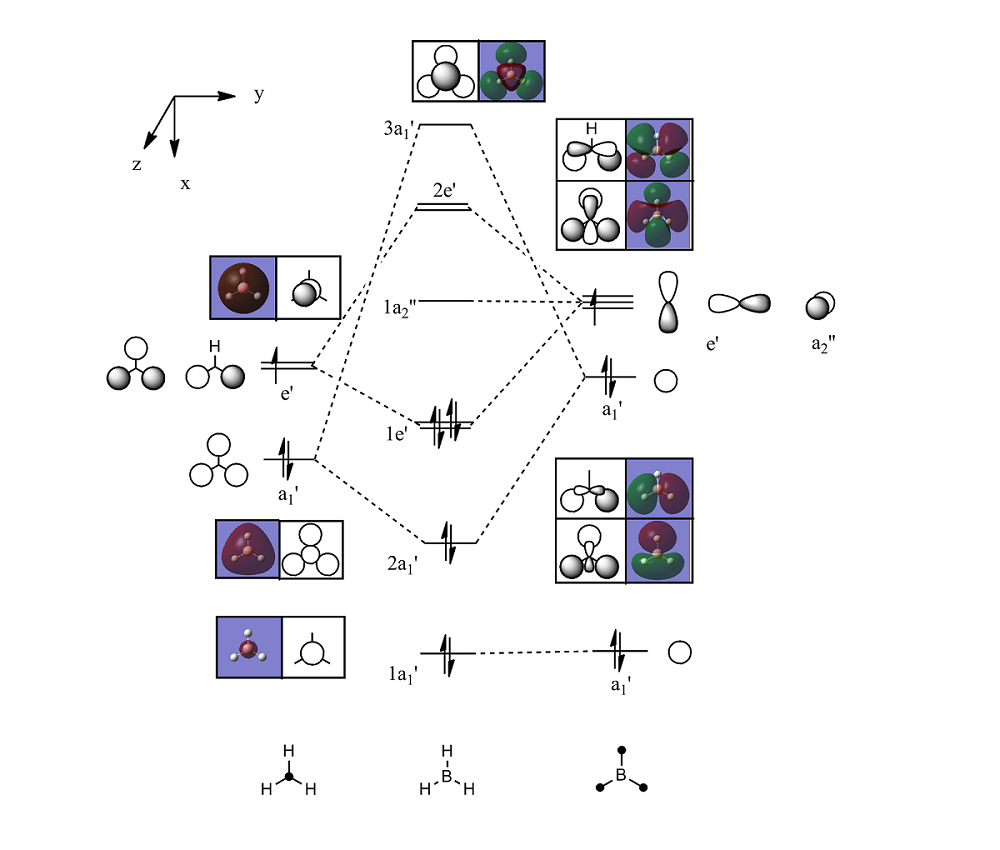

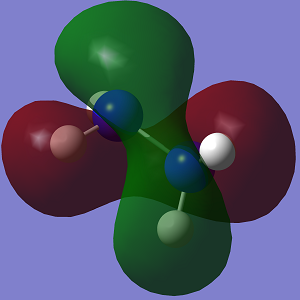

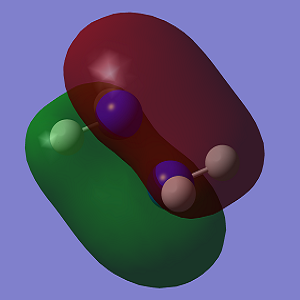

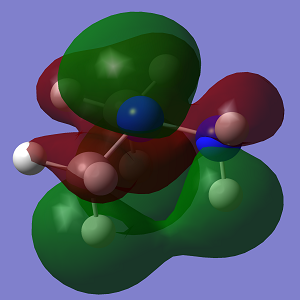

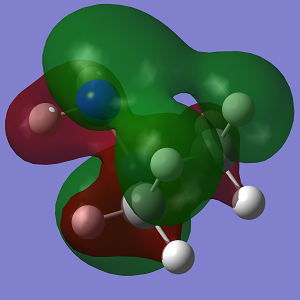

The checkpoint file (.chk) from the optimisation of BH3 was opened and a new Gaussian input file was created for MO analysis. This was submitted to the SCAN for computation. DOI:10042/to-6055 The .chk output file created was used to visualise the MOs. The molecular orbitals labelled 1-8 are shown. Looking at the MOs, it can be seen that the unoccuppied orbitals are more diffuse than the occupied ones, owing to the fact that they are of higher energy. Some orbitals also look slightly odd, such as MO 6.

The Gaussian produced MO diagrams agree reasonably well with the MOs predicted by qualitative MO theory. The general shapes of the molecular orbitals match up well although the nodes are not very well represented using only qualitative theory. By definition, qualitative MO theory does not give the energies of each MO and therefore it can be difficult to determine the position of certain MOs in relation to each other, such as the 3a1' MO being higher in energy than the 2e' MO. Therefore qualitative MO theory is relatively useful as a simple prediction due to the ease of usage, although to predict MOs to a higher degree computational methods are required.

The Gaussian produced MO diagrams agree reasonably well with the MOs predicted by qualitative MO theory. The general shapes of the molecular orbitals match up well although the nodes are not very well represented using only qualitative theory. By definition, qualitative MO theory does not give the energies of each MO and therefore it can be difficult to determine the position of certain MOs in relation to each other, such as the 3a1' MO being higher in energy than the 2e' MO. Therefore qualitative MO theory is relatively useful as a simple prediction due to the ease of usage, although to predict MOs to a higher degree computational methods are required.

NBO Analysis of BH3

The .log output file was opened and used to visualise the charge distribution within the molecule. As expected, the Lewis deficient boron atom is negatively charged and therefore the hydrogen atoms are left positively charged.

The .log file also contains information on the bond orbital coefficients and hybridisation, summarised in the table below.

| NBO | % Contribution | % Hybridisation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | H | s | p | |

| B1-H2 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B1-H3 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B1-H4 | 44.48 | 55.52 | 33.33 | 66.67 |

| B Core | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| B Lone Pair | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

The mixing between the MOs can be analysed by looking at the "Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis of Fock Matrix in NBO Basis". However in the molecule of BH3 this is not significant as none of the energies are greater than 1.5 kcal mol-1 or 6.32kJ mol-1.

The Natural Bond Orbitals summary gives the occupancy and energy of each of the NBOs.

| NBO | Occupancy | Energy/ kcal mol-1 |

|---|---|---|

| B1-H2 | 1.999 | -0.44 |

| B1-H3 | 1.999 | -0.44 |

| B1-H4 | 1.999 | -0.44 |

| B Core | 1.999 | -6.64 |

| B Lone Pair | 0.000 | 0.68 |

| Occupancy | |

| Total Lewis | 7.995 |

| Valence non-Lewis | 0.004 |

| Rydberg non-Lewis | 0.001 |

Vibrational Analysis and Confirming Minima

The optimised BH3 molecule was put through a frequency analysis run. The .log file was opened to look at the absorption freqeuncies of the molecule. The first six frequencies following the "Low frequencies" label are due to the negligible "-6" motions of the centre of mass of the molecule, of its possible 3N-6 vibrational modes. The largest of these comes to -67 cm-1 which is slightly high, due to the poor accuracy of this low level method.

The frequency analysis is related to the second derivative of the potential energy surface. The second derivative of the potential energy surface , gives the rate of change of the restoring force with respect to the distance. The frequency of a harmonic oscillator proportional to the square root of k.

The first vibration which has A2" symmetry has a frequency of 1144 cm-1 which is two orders of magnitude larger than the "zero" values. All the real frequencies are positive, confirming that the geometry of the molecule is a minima on the potential energy graph. Each of the vibrational modes and their frequencies is shown shown in the table below.

| Mode # | Form of Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry D3h point group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

1144 | 93 | A2' | |||

| 2 |

|

1204 | 12 | E' | |||

| 3 |

|

1204 | 12 | E' | |||

| 4 |

|

2598 | 0 | A1' | |||

| 5 |

|

2737 | 104 | E' | |||

| 6 |

|

2737 | 104 | E' |

The predicted IR spectrum from this calculation is shown below.

The number of peaks in the spectrum is less than the number of modes due to degeneracy between vibrational modes 2 and 3 and between 5 and 6. Vibrational mode 4 also doesn not appear as it has an intensity of 0.

Thallium Bromide, TlBr3

Pseudo-potentials and basis sets

When modelling a larger molecule such as TlBr3 we need to use much larger basis sets and pseudo-potentials due to the large number of electrons involved, a total of 186 electrons. In order to simplify the calculations, we assume that bonding interactions are predominantly due to the interactions of valence electrons and we can safely model the core electrons by a function known as the pseudo-potential (PP) or effective core potential (ECP).

Optimisation of the structure of TlBr3

A molecule of TlBr3 was created on GaussView and optimised in Gaussian. However before optimisation, the symmetry of the molecule was contrained to a high tolerance (0.0001) to the D3h point group. The molecule was optimised using the LANL2DZ basis set, a medium level basis set. It uses D95V on first row atoms and Los Alamos ECP (pseudo-potential) on heavier elements. The results and calculation method are shown in the summary below. Media:KC_TLBR3_OPTIMISATION.LOG

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

|---|---|

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -91.218 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000 a.u. |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Job cpu time | 25.0 seconds |

The optimised Tl-Br bond lengths and Br-Tl-Br bond angles were found and compared to literature values in a qualitative manner. This was to ensure the optimisation had worked reasonably.

| Experimental | Literature[1] | |

|---|---|---|

| Tl-Br bond length | 2.65Å | 2.563Å |

| Br-Tl-Br bond angle | 120° | 120° |

The literature value for the Tl-Br bond length is very close to the calculated value confirming that the computation was reasonable and is infact quite accurate. The bond angle of 120

Vibrational Analysis of TlBr3

The optimised TlBr3 molecule was submitted to Gaussian for frequency analysis. This was done to ensure that the geometry proposed corresponded to a minima on the potential energy curve. The same basis set has to be used in the frequency analysis as it is only valid to confirm a minimum using the same method and basis set. The .log file was opened in order to find the "Low frequencies".

| Frequency/ cm-1 | Real vibrational mode? |

|---|---|

| -3 | No |

| 0 | No |

| 0 | No |

| 0 | No |

| 4 | No |

| 4 | No |

| 46 | Yes |

| 46 | Yes |

| 52 | Yes |

The six "zero" frequencies are within 0±10 and this gives an indication of the slightly higher accuracy of this experiment.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

Introduction

The vibrational spectra of the cis and trans isomers of the Mo complex will be predicted using the methods shown previously. In this experiment, L = PPh3, but in order to reduce computational time, the large phenyl rings will be replaced with less computationally demanding Cl atoms. These have been shown to have a similar electronic contribution to the bonding as phenyl groups and are sterically relatively large.

The number of CO vibrational bands which are IR active is related to the symmetry of the complex. Four CO absorption bands are expected from the complex with cis ligands and only one band from the compound with the trans ligands. The point group of a cis-[Mo(CO)4L2] complex can be identified using a flow chart to be C2V. Each of the operations of the C2V group is then performed on the CO stretches using transformation matrices. The character (χ) contributing to the total reducible representation is then found by taking the trace of the transformation matrix.

The transformation matrices of the C2V point group are E, C2, σV and σV'. The reducible representation is then found by summing the characters of each transformation. ΓR = χE + χC2 + χσV + χσV' = 4 + 0 + 2 + 2 The reducible representation ΓR is then broken down into its irreducible components using the character table for the C2V point group and the reduction formula, given below.

nIR = 1/h ΣQ kχIR (Q) χR (Q)

h = number of operations in the group Q = a particular symmetry operation k = the number of operations of Q χIR(Q) = the character of the irreducible representation under Q χR(Q) = the character of the reducible representation under Q

Applying the formula gives the irreducible representation, ΓIR = 2A1 + B1 + B2. Looking at the C2V character table, each of the symmetry labels A1, B1 and B2 correspond to the three translation coordinates Tx, Ty and Tz and so they transform as does one of the components of the dipole moment operator. [2] Vibrational transitions between states in these modes are therefore allowed and all four modes are infrared active. The projection operator can be used to give the coordinates of the each of the CO modes of vibration. Therefore cis-[Mo(CO)4L2] complexes will show four absorption bands in the CO stretch region.

Carrying out the same exercise for a trans-[Mo(CO)4L2] complex with D4h symmetry gives the irreducible representation, ΓIR = A1g + B1g + Eu. However looking at the D4h character table shows that only the Eu symmetry label transforms as a component of the dipole moment operator and so is the only infrared active mode. Therefore in the IR spectrum of trans-[Mo(CO)4L2] complexes, only one absorption band will be visible in the CO stretch region.

Optimisation of Mo(CO)4L2

A molecule of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 was created and optimised in Gaussian using the LANL2MB basis set. An additional "opt=loose" convergence criteria had to be added, as the method employed is less accurate than the default convergence criteria limits.

| cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2MB | LANL2MB |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -617.525 a.u. | -617.522 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00026 a.u. | 0.00006 |

| Dipole Moment | 8.83 Debye | 0.00 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 9 minutes 40.8 seconds | 5 minutes 1.0 seconds |

However this low level of optimisation is insufficient and the rotation of the PCl3 groups is poorly described. Due to the presence of multiple minima in the potential energy curve, it is easy for the calculation to converge to the wrong minima if the starting geometry is not correct. Therefore after the first LANL2MB basis set optimisation had been carried out, the PCl3 groups were rotated in order to ensure that the following optimisation would converge towards the true minimum.

- Cis Conformer: One Cl points up parallel to the axial bond and a Cl from the other group points down.

- Trans Conformer: Both PCl3 groups are eclipsed and one Cl of each group lies parallel to one Mo-C bond.

The additional keywords "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9" were also added to increase the electronic convergence. The basis set used for the second optimisation was a LANL2DZ basis set.

| cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -623.577 a.u. | -623.576 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00001 a.u. | 0.00004 |

| Dipole Moment | 1.31 Debye | 0.31 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 46 minutes 47.7 seconds | 49 minutes 43.9 seconds |

Unfortunately the LANL2DZ pseudo-potential and associated basis set only give the phosphorus atom a minimal basis (valence s and p orbital functions). However P can be hypervalent though bonding with its low lying d atomic orbitals. GaussView is not able to add the dAO functions and so they were added to the input file manually. The previous .log file was saved as a .gjf file and edited. The keyword "extrabasis" was added and a D function was added to the end of the file.

(blank line)

P 0

D 1 1.0

0.55 0.100D+01

****

(blank line)

This input file was then resubmitted to the SCAN and the .log files from this third optimisation were used in the subsequent frequency analysis.

| cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | Gen | Gen |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -623.693 a.u. | -623.694 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00006 a.u. | 0.00000 |

| Dipole Moment | 0.07 Debye | 0.23 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 35 minutes 42.3 seconds | 36 minutes 29.5 seconds |

| Optimisation file | DOI:10042/to-6071 | DOI:10042/to-6073 |

The results show that the final optimisation, taking into consideration the dAOs of the phosphorus atom, gives a geometry of a very slightly lower energy than carrying out an optimisation using the LANL2DZ basis set. The results show that the trans isomer is around 3 kJ mol-1 more stable than the cis isomer, a small difference in energy. This energy difference is due to the steric strain in the cis-isomer, where the two PCl3 groups are adjacent to each other. CHECK DIPOLE MOMENT. Therefore, in order to alter the stability of the cis and trans isomers relative to each other, the size of the PR3 group can be changed. Large, bulky PR3 groups, such as PPh3 will favour the trans isomer, whereas smaller groups will favour the cis isomer.

Vibrational Analysis of Mo(CO)4L2

The frequency analysis was carried out on the optimised geometry of the cis and trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 in the same way as the final optimisation, except with the changed method. The computational time was 37 minutes 42.6 seconds for the cis isomer and 31 minutes 34.7 seconds for the trans isomer.

The .log file was checked for both isomers to confirm that the geometry found was indeed a minimum in energy. None of the frequencies were negative, except for very small negative numbers for the 'zero' frequencies. The 'zero' frequencies in the cis isomer were very small, ranging from -1 to 2, and slightly larger for the trans isomer, from -2 to 3, showing that the basis set gave results to a relatively high accuracy compared to earlier basis sets used. The .log files for the frequency analysis can be accessed through the links below.

| Cis isomer | DOI:10042/to-6074 |

| Trans isomer | DOI:10042/to-6075 |

Discussion and Comparison to Literature

The bond lengths and bond angles of the optimised geometry were compared to literature[3] values for a similar compound, Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2. Literature values could only be found for the trans isomer.

| Bond length | Calculated value/ Å | Literature value/ Å |

|---|---|---|

| Mo-P | 2.42 | 2.500 |

| Mo-C | 2.06 | 2.016 |

| P-C (Cl) | 2.12 | 1.840 |

| C=O | 1.17 | 1.164 |

| Bond angle | Calculated value/ ° | Literature value/ ° |

| P-Mo-P | 177 | 180.0 |

| P-Mo-C | 92 | 92.0 |

| cis C-Mo-C | 91 | 92.1 |

| trans C-Mo-C | 180 | 180.0 |

The geometry of the Gaussian optimised structure is generally in agreement with literature. The angles and bond lengths are very similar except for the differing P-C and P-Cl bond length. The Gaussian optimised geoemtry also does not have a 180° P-Mo-P bond angle as found in the literature.

The low frequency vibrational modes for the cis and trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers are shown below.

| Cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mode # | Form of Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Mode # | Form of Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | ||||||

| 1 |

|

12 | 0 | 1 |

|

4 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 |

|

20 | 0 | 2 |

|

7 | 0 | ||||||

The vibrational modes of low frequency are low energy vibrations and so they can occur at room temperature as there is enough energy kBT in order to cause excitations between the vibrational levels. All the low frequency modes of vibration involve twisting of the Mo-P bond either in a conrotatory fashion or a disrotatory fashion. The intensity of each of the absorptiom frequencies is very low, and appears as 0 due to rounding.

The Gaussian calculated C=O stretch frequencies in each isomer were identified and compared to experimental (from Second Year experiment 5) and literature[4] values for Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2.

| Symmetry | Gaussian | Literature (Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2)[5]/ cm-1 | Experimental (Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2)/ cm-1 | Literature (Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2)[4]/ cm-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Frequency/ cm-1 | ||||

| A1(2) | 545 | 2019 | 2072 | 2014 | 2023 |

| A1(1) | 588 | 1952 | 2004 | 1917 | 1927 |

| B1 | 813 | 1941 | 1994 | 1903 | 1908 |

| B2 | 1605 | 1938 | 1986 | 1890 | 1897 |

| Symmetry | Gaussian | Literature (Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2)[6]/ cm-1 | Experimental (Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2)/ cm-1 | Literature (Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2)[4]/ cm-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | Frequency/ cm-1 | ||||

| A1g | 5 | 2026 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| B1g | 6 | 1967 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Eu | 1606 | 1940 | 1896 | 1893 | 1908 |

| Eu | 1606 | 1939 | 1896 | 1893 | 1902 |

The Gaussian values for the absorption frequencies match the literature values for Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 but they are no greatly accurate for either isomer. However comparing these values to the experimental and literature values for cis Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 shows that the replacement of the phenyl group with a chlorine atom can have a significant effect on the C=O stretching frequecies. The effect in the trans isomer appears to be less significant. Gaussian predicts four stretching modes for the trans isomer but only two of these modes are IR active and seen in literature, the degenerate Eu stretching modes. The other two stretching modes do not result in a change in dipole moment, as explained before, and therefore do not appear in the IR spectra.

Mini Project

The aim of this project is to investigate the conformations of hydrazine and to carry out calculations on several possible conformations to determine why conformation with the lone pair orbitals almost perpendicular[7] is preferred. The structure of two hydrazine derivatives would then be investigated to determine if these substituents would change the preferred geometry.

Hydrazine

The structure of hydrazine may at first be predicted to contain two tetrahedral nitrogen atoms with the lone pairs antiperiplanar to each other. None of the hydrogen atoms are eclipsed, reducing steric strain, and the lone pairs are as far apart from each other as possible, reducing the coulombic repulsive force between them. However this was found not to be the case, and in fact the conformation with the lone pair orbitals at almost 90° to each other is more stable. This is due to interactions between the lone pairs on each nitrogen atom , which will be investigated in this section.

Three starting geometries were drawn on GaussView as starting points for optimisation. The first was the antiperiplanar structure (no lone pair-lone pair interactions), the second was the synperiplanar structure (large amount of lone pair-lone pair interactions) and the third was the gauche structure (some lone pair-lone pair interactions). Each of the starting geometries was first optimised using the B3LYP method and a simple 3G basis set before undergoing a more rigorous optimisation using the MP2 method and a 6G (d,p) basis set.

As expected, the synperiplanar conformation was found not to be a minimum in energy and it was optimised to the same geometry as the gauche conformation after running the MP2 method. The antiperiplanar starting geometry however optimised to a different minimum energy geometry. The calculation summaries are shown below.

| app N2H4 | gauche N2H4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Jmol | ||

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RMP2-FC | RMP2-FC |

| Basis Set | 6-311G(d,p) | 6-311G(d,p) |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -111.580 a.u. | -111.584 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000 a.u. | 0.00000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.00 Debye | 2.19 Debye |

| Point Group | C2h | C2 |

| Job cpu time | 46.4 seconds | 55.6 seconds |

Looking at the actual geometry of each conformation, it can be seen that the antiperiplanar conformation (Conformation 2) does remain with the lone pairs at around 180° to each other. However the nitrogen-nitrogen bond in the gauche conformation was rotated during the optimisation to the perpendicular lone pair geometry described before (Conformation 1).

A vibrational analysis was carried out to confirm that both geometries found were indeed minima. Both optimised geometries did not contain negative frequencies. The 'zero' frequencies for both optimisations were also quite small. In Conformation 2, the 'zero' frequencies range from 0 to 4 and in Conformation 1 from -4 to 2.

The IR spectrum for the Conformation 1 and the vibrational modes are shown below.

| Mode # | Form of Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | Mode # | Form of Vibration | Frequency/ cm-1 | Intensity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

438 | 43 | 7 |

|

1680 | 15 | ||||||

| 2 |

|

892 | 68 | 8 |

|

1702 | 13 | ||||||

| 3 |

|

1059 | 141 | 9 |

|

3514 | 13 | ||||||

| 4 |

|

1159 | 12 | 10 |

|

3522 | 2 | ||||||

| 5 |

|

2737 | 104 | 11 |

|

3634 | 0 | ||||||

| 6 |

|

1365 | 7 | 12 |

|

3639 | 2 |

| Conformation 1 | DOI:10042/to-6105 |

| Conformation 2 | DOI:10042/to-6106 |

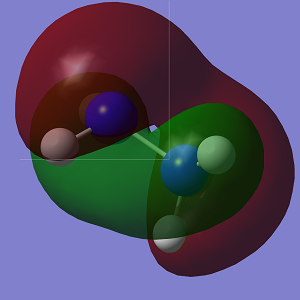

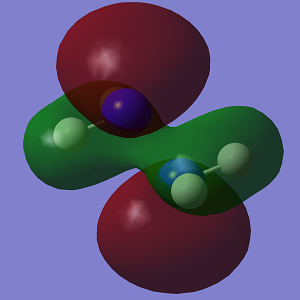

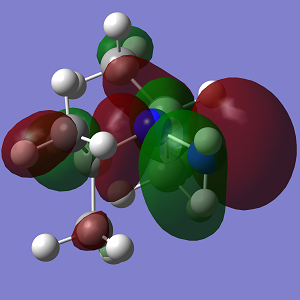

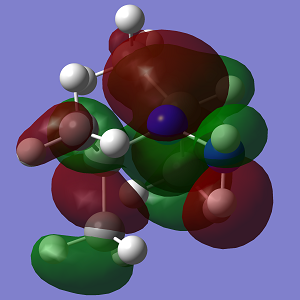

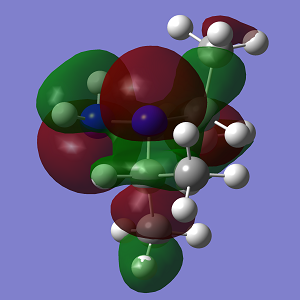

The molecular orbitals of both conformations were calculated and visualised in GaussView. A visual representation of the HOMO-1 and HOMO for both conformations is shown below.

| MO | Conformation 1 | Conformation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

| Energy | -0.412 | -0.541 |

| HOMO |  |

|

| Energy | -0.407 | -0.361 |

The HOMO of Conformation 1 is lower in energy than the HOMO of Conformation 2. In the MO visualisations, it can be seen that there is a lone pair-lone pair interaction in Conformation 1 which reduces the 'amount' of destabilising anti-bonding interactions and increases the 'amount' of stabilising bonding interactions. However the HOMO-1 in Conformation 1 is not as stable as in Conformation 2.

1,1 Dimethylhydrazine (UDMH)

The two hydrogen atoms on one of the nitrogen atoms in hydrazine were replaced with methyl -CH3 groups. This structure was optimised from two different starting geometries, the antiperiplanar and gauche conformations, using the same methods as before. The results of the optimisations are summarised below.

| app Conformation | gauche Conformation | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RMP2-FC | RMP2-FC |

| Basis Set | 6-311G(d,p) | 6-311G(d,p) |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) | -189.959 a.u. | -189.963 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000 a.u. | 0.00000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.45 Debye | 1.85 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 5 minutes 46.3 seconds | 6 minutes 36.4 seconds |

The geometries found were confirmed to be minima by vibrational analysis. The antiperiplanar conformation had 'zero' frequencies ranging from -1 to 0 and the gauche conformation had 'zero' frequencies from -1 to 1.

| Conformation 1 | DOI:10042/to-6102 |

| Conformation 2 | DOI:10042/to-6103 |

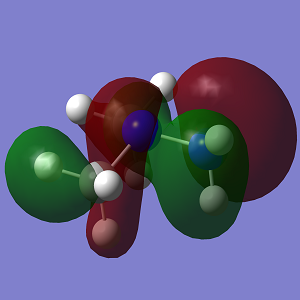

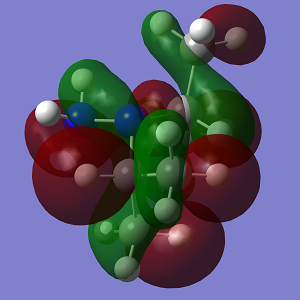

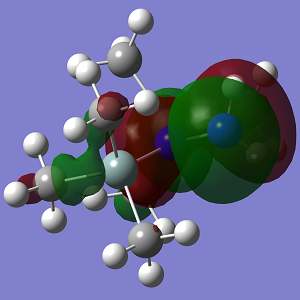

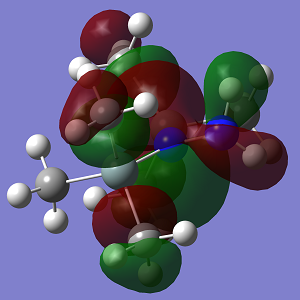

The HOMO-1 and HOMO were then calculated for the two conformations.

| MO | Conformation 1 | Conformation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

| Energy | -0.411 | -0.480 |

| HOMO |  |

|

| Energy | -0.369 | -0.342 |

Looking at the MO diagrams it can be see that the lone pair-lone pair interactions in Conformation 1 are no longer as significant and cannot be seen as clearly in the diagram. However the increasing steric strain in the substituents will push them further apart and closer to the hydrogen atoms of the opposing nitrogen atom and this will destabilise the anti conformation. This will become more apparent with larger substituents.

1,1-Diisopropylhydrazine

The methyl substituents were replaced with more bulky isopropyl substituents. The same optimisations as before were carried out.

| app Conformation | gauche Conformation | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RMP2-FC | RMP2-FC |

| Basis Set | 6-311G(d,p) | 6-311G(d,p) |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(MP2) | -346.744 a.u. | -346.749 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000 a.u. | 0.00000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0.45 Debye | 1.49 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 4 hr 23 min 43.2 sec | 4 hr 40 min 1.9 sec |

A frequency analysis was carried out to confirm that the geometries were minima.

| Conformation 1 | DOI:10042/to-6099 |

| Conformation 2 | DOI:10042/to-6100 |

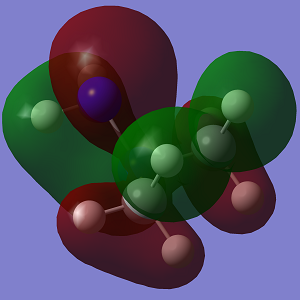

The MOs were then calculated.

| MO | Conformation 1 | Conformation 2 |

|---|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |  |

|

| Energy | -0.400 | -0.449 |

| HOMO |  |

|

| Energy | -0.349 | -0.327 |

The increasing steric strain from the larger isopropyl groups destabilises Conformation 2 to a greater extent.

1,1-Bis(trimethylsilyl)hydrazine

Huge trimethylsilyl substituents were put on the hydrazine to give large steric repulsions and observe the effect on the nitrogen lone pair. During optimisation, the antiperiplanar conformation was found to no longer be a minimum in energy and it shifted to the perpendicular lone pair geometry.

| Conformation 1 | |

|---|---|

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| E(MP2) | -357.983 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 1.45 Debye |

| Point Group | C1 |

| Job cpu time | 1 hr 0 min 14.7 sec |

A frequency analysis was carried out to confirm the minimum geometry. DOI:10042/to-6101

| MO | Conformation 1 |

|---|---|

| HOMO-1 |

|

| Energy | -0.226 |

| HOMO |

|

| Energy | -0.216 |

The trimethylsilyl groups are so bulky that the geometry around the nitrogen atom is almost trigonal planar. This puts the trimethylsilyl groups very close to the hydrogen atoms on the opposing hydrogen in the anti position, and therefore this conformation is destabilised to the extent it is no longer a minimum and there is only one possible conformation.

References

- ↑ M.R. Bernejo et al., Polyhedron, 1988, 7, 2561-2567 DOI:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)83874-7

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg and M. Y. Darensbourg, J. Chem. Ed. 1970, 47, 33 DOI:10.1021/ed047p33

- ↑ G. Hogarth and T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem, 1978, 17 2680-2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ ELmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995 34, 3864-3873 DOI:10.1021/ic00119a006

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, Inorg. Chem., 1964, 3, 702-711 DOI:10.1021/ic50015a024

- ↑ S. F. Nelsen et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1977, 99, 4461-4467 DOI:10.1021/ja00455a041