Rep:Mod2:hgiaffar

Module 2 - Inorganic Computational Lab

Small D3h Molecule

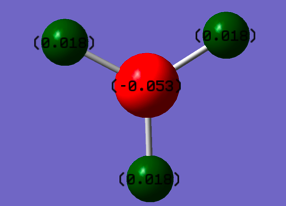

Borane - BH3

The Gaussview interface was used to visually display the results of a an optimisation run on BH3 by Gaussian (using the B3LYP method and 3-21G basis set).

| The Optimised Structure of Borane | |||

|

Having run the optimisation of the molecule on this basis, the results were presented in a summery file (calculation type: FOPT, file type is .log), and gave the final energy as -26.46226438 a.u with a corresponding gradient of 0.00000285 a.u. (which is well below the threshold value of 0.001 a.u.). The success of this calculation was confirmed by the convergence demonstrated in the output file (checked graphically and manually in the transcript).

Molecular Orbitals of Borane

The calculated MOs bear a strong structural resemblance to those taken from a simple qualitative LCAO approach; this demonstrates the power of computational chemistry in providing a realistic realization of this important theory.

There is little to say about the information collected above, as expected the LCAO approach yielded highly illustrative molecular orbitals which provide a quantitative basis for understanding the chemical behavior of borane. The qualitative analysis as shown in the diagram taken from Dr Hunt's notes is in strong agreement with the calculated orbitals.

NBOs of Borane

The calculated natural Bonding orbitals provide a basis for analysing the distribution of charge within a molecule, this in turn leads to an understanding of the extent of hybridisation within a molecule. The overall charge of the molecule was, as expected, calculated to be zero; the separation of charge also closely followed chemical intuition with the more strongly electropositive boron atom taking a charge of +0.331 (relative to the -0.110 of each hydrogen). This information can be extrapolated to give relative values for the contribution of each constituent hybrid orbital to the overall bonding orbital, with the ratio of bond contribution is 44.5:55.5 (66.6:33.3 p:s) boron hybrid orbital : hydrogen s orbital.

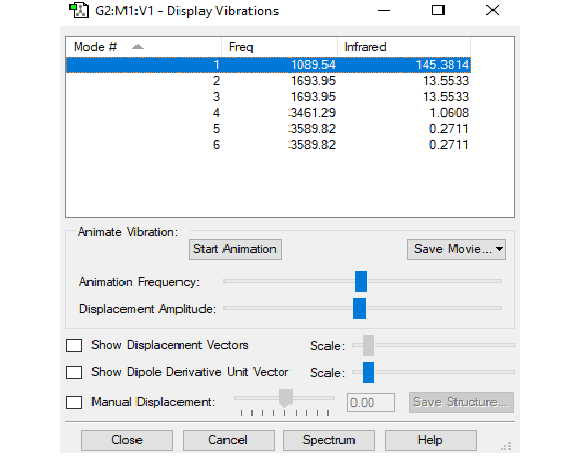

Vibrations of Borane

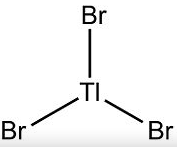

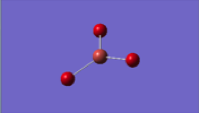

Thallium Bromide - TlBr3

The Gaussview interface was used to visually display the results of a an optimisation run on BH3 by Gaussian (using the RB3LYP method and LANL2DZ basis set), again, the calculation type is FOPT, file type is .log.

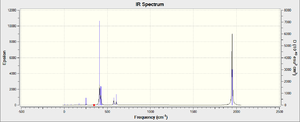

| Low frequencies (cm-1) | -3.42 | -0.0026 | -0.0004 | 0.0015 | 3.9367 | 3.9367 |

| "Real" normal frequencies (cm-1) | 49.98 | 49.98 | 57.46 | 150.77 | 195.01 | 195.01 |

| Tl-Br bond distance | Br-Tl-Br bond angle |

|---|---|

| 2.65 Å | 120.0 o |

The above results correspond reasonably well with literature values. With no geometry contorting factors to consider, any deviation from an angle of 120 degrees would have been indicative of a failed optimisation, as it was the recorded angle corresponded exactly with chemical intuition. The calculated bond length was somewhat more exaggerated when compared to the literature value of 2.5153 angstroms [1]

It is essential to employ the same method and basis set in both calculations in order to ensure that the results are directly comparable and consistent.

Frequency analysis is a numerical method that has been developed to find the ground state of a molecule by iteratively studying its potential energy surface. The ground state of a molecule is by definition, the most stable thermodynamic state that the molecular system can exist in, and therefore it is obviously beneficial to discover the molecular geometry that corresponds to this energy.

The method relies on altering the value of a particular parameter in order to study the effect on the potential energy of the system, and consequently on the first derivative of the potential energy (equal to the force); when a certain perturbation leaves the potential energy of the molecule as equal to zero, there is no force that requires balancing, and so the molecule is said to be at either a transition state or a ground state. the nature of this stationary point is determined by taking the second derivative of the potential energy curve at the point of interest, with a positive value indicating a local minimum, and a negative value corresponding to a local maximum. If all the molecular vibrations are positive, this corresponds to a minimum, and hence the ground state of a molecule. Consequently, if any of the vibrations are negative, the optimisation result does not correspond to the ground state of the molecule. The low frequencies are the ones that provide the information regarding the point on the potential energy surface under consideration. In this calculation, all the low frequencies were greater than 0, indicating that the optimised structure is a local minimum and therefore not a transition state; the lowest "real" normal mode is at 46cm-1.

Gaussview draws bonds based on certain criteria, and draws a large amount of information from a chemical database (based primarily on organic molecules); these criteria determine, for each pair of atoms, whether or not there is sufficient electronic interaction to be considered a localised bond. As this is the case, optimisation results can sometimes come back without one or more of the bars that are usually drawn to represent a bond. This does not indicate that there is no bonding interaction, but rather that the configuration does not conform to one of the systems distance criteria.

This analysis in turn leads to questions regarding the nature of bonding; a workable definition depends on the particular theory invoked in the calculations. The basis of this computational lab is an investigation of the calculated molecular orbitals of an inorganic compound, and with this in mind, a bond can be described as a localised, overwhelmingly positive superposition of the individual constituent atomic/molecular orbitals. Far from being an esoteric concept, bonding is often described simply as a useful practical tool, escaping any rigid definition.

This file has been uploaded to D-space.[2]

Geometric Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

| Optimised cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2complex | Optimised trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2complex | ||||||

|

|

Molecular Parameters for the Different Isomers

The literature values for the Mo-P bond length (using PPh3) do not correspond exactly to those calculated using the computational simulation (with the phosphorus bearing ligand being of the form PCl3). This indicates that the earlier approximation that Cl and Ph were roughly equivalent (at least in terms of electronic effects) was not exactly accurate. The reason for the discrepancy could be based in the unfavourable steric interactions between the bulkier phenyl groups; with a longer Mo-P bond length comes a reduced ligand cone angle. This is reflected most obviously in the P-Mo-P bond angle, with the cis complex exhibiting an angle of 94.3 degrees, significantly different from that found in the literature (104 degrees. The C-Mo-C bond angle is affected by the exact steric nature of the phosphine ligand; the cis complex exhibits a reduced angle (from the 90 degrees expected by application of CFT using point charges) at 87.1 degrees, while the corresponding angle in the trans complex is much closer. It is particularly important to note that it is in fact the cis-bound complex that shows a greater divergence from literature values. As expected (from crystal field theory), this relative lengthening of the Mo-P bond is concurrent with a shortening of the Mo-C bond (again, the calculated value is in weaker agreement with the literature to a greater extent in the cis complex).

| Bond length /Å | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond | Trans-isomer | Cis-isomer | ||

| Computed | Literature | Computed | Literature | |

| Mo-C | 2. | 2.005 and 2.016 | 2.06 and 2.01 | |

| Mo-P | 2.44 | 2.500 | 2.51 | 2.577 |

Vibrational Analysis

</jmolAppletButton> </jmol>

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Type | Symmetry label | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 408.81 | 727.75 | Symmetric Mo-P stretch | ||

| 574.12 and 574.30 | trans pair C=O bends | |||

| 603.56 | all 4 C=O bends | |||

| 1977.40 | 1606 | trans pair C=O asymmetric stretches | ||

| 1950,50 and 1951.12 | 1466.79 | all 4 C=O asymmetric stretches |

This file has been saved to D-space [3]

| Vibration | Animation | Frequency (cm-1) | Symmetry label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

1550.50 | e' |

| 2 |  |

1551.12 | e' |

| 3 |  |

1203.64 | e' |

</jmolAppletButton> </jmol>

| Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 567.56 | 78.02 | Ax. C=O bends | ||

| 578.54 | 187.23 | Eq. C=O bends | ||

| 1927.12 | 1611.33 | cis-pair C=O asymmetric stretches | ||

| 1939.50 | 876.45 | trans-pair C=O asymmetric stretches | ||

| 1948.88 | 409.11 | Four C=O asymmetric stretches | ||

| 2009.12 | 421.40 | Four C=O symmetric stretches |

This file has been saved to D-space [4]

The above IR spectra, and associated vibrations show a certain structural correspondence with those found in the literature. Firstly, the peaks associated with coordinated C=O’s all appear at a lower frequency than the literature value for a free C=O stretch (2143cm-1), this is caused by a certain degree of backbonding from the metal d orbitals into the π* orbital of the CO ligand, this causes a weakening of the bond and hence a lowering of the bond energy (synergic bonding).

Application of this concept to the two isomers reveals a split in the expected CO vibrations; symmetry considerations put the CO ligands in the trans complex in equivalent environments, whereas in the cis complex, there can be seen to be a difference between the axial and equatorial constutuents. This leads to an expectation that the stretching frequency for each of the two trans pairs would be equal (practically demonstrated in the spectrum, as they almost ie at the same energy) , and that those of the cis CO ligands would be unequal (four separate frequencies).

Comparison of the Relative Thermodynamic Energies

| Isomer | Energy /Atomic Units | Energy /kJ/mol |

|---|---|---|

| Cis | -623.693 ± 0.005 | 1637500 ± ~10 |

| Trans | -623.694 ± 0.005 | -1637500 ± ~10 |

The trans-isomer has been calculated to be the most thermodynamically stable of the two isomers. There is a certain physical basis for rationalising this result; it could be argued that the steric clash between the bulky PPh3 groups could raise the energy of the cis isomer relative to the trans isomer, this is supported by a computational assessment of the same problem in the literature.[5] This is not a conclusive result however, as this falls well with in the limits for error in the calculation (roughly10%).[6]

This problem provides an interesting base for computational research with the prospect of reducing the steric size of the two ligands on the molybdenum to see if there is a more fundamental energy difference between the isomers (rather than steric clash, or any kind of inter-ligand electronic interaction).

Mini Project

Computational techniques allow a thorough investigation of the properties pertaining to a large range of molecules. In this short analysis, the electronic properties of a the catalyst [Au(NHC)Cl] will be examined; with a particular emphasis on the effects of the recently developed NHC (Nitrogen Heterocyclic carbene) ligand as a replacement for the more traditionally used phosphorus trialkyl (R - a substituted phenyl of some description) ligand. These NHC ligands, while obviating the need for a silver salt to precipitate the halide, are presumed to act primarily as a phosphine mimic, with altered selectivity as only a secondary concern; this project will seek to model both complexes ([Au(NHC)Cl], and [Au(PR3)Cl] in order to determine if this is the case in the electronic sense.

The synthesis of these catalytic systems is relatively facile, and is reported to proceed in high yield according to the following scheme[7]

These catalysts have been optimised according to the preceding method, but with a particular pseudo-potential used to deal with the now relevant relativistic effects (for lighter atoms, these do not play any significant role, and so are approximated as such) - namely the LanL2DZ basis set.

NBO analysis of all four compounds under consideration

The localised charge distribution in the molecule can be analysed by means of the NBO calculations, the results of which were not particularly encouraging. The NHC complex proved very difficult to model, with the system seemingly incapable of accepting the molecular geometry demanded by the NHC ligand; this resulted in a NBO distribution which contradicts both experimental and theoretical results[8][9]. The calculations were repeated five times; each time, a different approach was used in order to make the molecular geometry conform to the the strict parameters of the gaussview interface. This was ultimately possible, and the results of the anlaysis are shown below, in which the charge distribution is shown to be similar at both the metal centre and the directly bonded point of the non-Cl ligand; the terminal Cl ligand NBO values also agree (to be expected due to the lack of exchange interaction with other parts of the molecule)

Having accepted the limitations and problems that have dogged the analysis of the NHC ligand, a calculative reexamination of the electronic similarity between the PR3 and NHC ligands has been pursued: the overwhelming consensus of the literature (wrt. the similarities between NHC and PR3) will be accepted, and used as a platform for an investigation into the structures of gold and related metal catalysts, with the PR3 (R=Cl, as aromatic R groups and Cl have similar electronic properties) ligand as a replacement for NHC.

Orbital Calculations on ClAu(PR3)

Obtaining orbital information for these compounds proved extremely challenging, eventually it was decided that for the ClAu(PR3) catalyst, the 6-311G(d,p) basis set was run with RB3LPY method. This seems to have yielded good results; the orbitals are shown below

| Molecular Orbital | HOMO-2 | HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 |

| Gaussview representation |  |

|

|

|

|

| Energy | -5.130 | -1.517 | -0.856 | -0.356 | -0.074 |

The calculated orbitals above are very interesting, they would seem to indicate that the HOMO and HOMO-1 are completely localised on the Cl ligand, and seem to be of odd parity, l=1 form; with no literature MO diagram to compare it to, a definitive assignment would not be possible. It is very unfortunate that the MO calculations repeatedly failed for the NHC complex as this would have provided very interesting information.

A Comparative Vibrational Analysis

Again, the stretching modes of the two molecules have been calculated, for the heavier Gold(NHC) molecule, again this was run with the LanL2DZ basis set. All low frequencies were calculated as positive and as such correspond to energy minima.[10]

</jmolAppletButton> </jmol>

| Vibration | Animation | Frequency (cm-1) | Symmetry label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

489.26 | e' |

| 2 |  |

489.36 | e' |

| 3 |  |

540.54 | a"2 |

| Vibration | Animation | Frequency (cm-1) | Symmetry label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

726.11 | a'1 |

| 2 |  |

1333.48 | a"2 |

| 3 |  |

3327.57 | a"2 |

Conclusions

Reactivity can be rationalised in a number of different ways; from charge density considerations (essentially calculated NBOs), an understanding of primarily electrostatic chemical interactions can be understood, whereas the calculated orbitals give a good indication of the feasibility of reactions based on orbital considerations. In the first instance, a comparison of the NBO local charge distribution provides encouraging results, with a similar gradient running across both molecules, it seems that the experimental results regarding the chemical equivalence of NHCs and PR3 would seem to have a strong physical basis. Again, it is very unfortunate that MOs for the NHC complex could not be calculated, they could have shown whether or not the orbital structure was similar - in which case, the total electronic architecture would have been comparable between the two types of complex (it also happens that the relativistic effects on the MO shape could not be analysed).

References

- ↑ J. Glaser, G. Johansson. Acta Chemica Scandinavica A 36 (1982) 125-135

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/to-5533

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5414

- ↑ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5417

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14 DOI:10.1021/ic50191a003

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/8a_accuracy.html

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ar1000764

- ↑ http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/cr8005153

- ↑ http://www.scripps.edu/chem/baran/images/grpmtgpdf/Eastman_May_07.pdf

- ↑ https://spectradspace.lib.imperial.ac.uk:8443/dspace/handle/10042/to-5531