Rep:Mod2:eb108

Module 2: Inorganic computational lab

The aim of this module is to computationally predict the bonding of inorganic molecules and compare this to theoretical methods. For example, using LCAO to predict MO's and comparing them to computationally modelled MO's. Using reasonably simple molecules, a variety of techniques to compute different properties of molecules are demonstrated throughout this module.

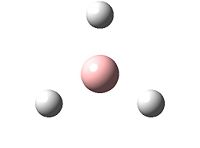

Borane BH3

|

Using gaussveiw, this molecule was drawn out and the bond lengths were set to 1.5 (angstroms). Then the molecule was optimised using the B3LYP method and the 3-21G basis set. The 3-21G is a basis set with a very low accuracy but since this is a relatively simple molecule it is possible to get reasonable results with it and the calculations run very quickly. The table 1 shows some of the characteristics of the optimised molecule.

| Bond length | 1.19Å |

| Bond Angle | 120.0o |

| Energy | -26.46353 a.u. (-6.94E4 kJ/mol) |

The summary file in gaussveiw gives information on the optimisation. The file type is a .log, the calculation type is FOPT with the RB3LYP method and using the 3-21G basis set. The charge is 0, the spin is singlet, the dipole moment is 0.00 Debye. The RMS gradient norm is 0.00020672 a.u. which is much less than the threshold value of 0.001 that indicates that this calculation has been a success. The point group D3h and the calculation took 32.0 seconds to run.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

The published population can be found here

Analysis of the optimisation gives the following graphs:

|

|

Gaussian optimises the molecule using the basis set and modifies the structure. This modified structure is analysed to determine the difference between attractive and repulsive force and is then reconfigured to give a structure with a lower energy. Each time the structure is modified the energy decreases and the energy difference between successive configurations also decreases. The RMS gradient is a measure of the energy difference between configurations and tends towards zero. However, once the RMS gradient reaches a threshold value (0.001 in this case) the energy is deemed to be close enough to the minimum energy and the reaction ends.

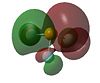

The Molecular orbitals of borane

It is possible to using computational methods to calculate the MO diagrams for each energy level with borane and to compare these to the qualitative LCAO MO's obtained using a simple MO diagram. The calculation was run using the same basis set and method as before but with the keywords "pop-full" added and with the "full NBO" option enabled.

The published population can be found here

Using the LCAO method to predict MO's it is possible to get a qualitative picture of the orbitals. However it is often difficult to predict the relative energies of the orbitals. In this case, we need to use computational method to determine whether the 3a1' orbital or the degenerate 2e' orbitals are higher in energy. The results show that the 2e' are higher in energy. Comparing the qualitative LCAO MO's with the quantitative MO's calculated using gaussian we can see that the occupied MO's fit much better than the unoccupied MO's. This is because the system for drawing LCAO MO's is set up for the occupied orbitals and does not work so well for the unoccupied ones. The computed MO's take all orbital interactions into account whereas the LCAO MO's only take the strongest orbital interactions into account. The unoccupied orbitals are more diffuse and so interactions that would be negligible in the occupied MO's become noticeable in the unoccupied MO's. The LUMO fits reasonably well but the orbitals are much more diffuse in the computed MO than in the LCAO MO. The LUMO+1 fits well if you look down the z-plane but when the molecule is tilted it is possible to see that s-orbital on the boron is distorted. The LUMO+2 looks very different from the LCAO MO since the computed MO takes into account to repulsion between the p-orbital on the boron and the s-orbitals on the hydrogens and so this p-orbital is distorted away from the hydrogen atoms. The LUMO+3 looks very different from the qualitative MO. The accuracy of the LCAO method decreases for higher energy unoccupied MO's, for this reason the lCAO method is only useful for occupied MO's in small molecules.

|

The Natural Bond Orbitals of Borane

|

It is possible to use Gaussian to analyse the relative contribution from each atom in individual bonds. The output file from the optimised borane was used. The charges on the atoms can be visualised in Gaussview with bright green indicating a very positive atom and bright red a very negative atom. The boron atom in borane is bright green as it is very lewis deficient and the hydrogen atoms are a dull red as they are only slightly negative. The value of the charges is also indicated on each atom in fig 3 (0.278 for B, -0.098 for each H). Gaussview provides a graphical interface for picturing the atomic charges but by using the log file, a slightly more detailed look at the NBO's allows us to analyse the borane molecule further. This is because the NBO analysis partitions the electron density like orbitals to give an "organic chemist's" 2e-2c picture of bonding[1]. We can now tell what proportion of each bond is due to each atom. There are three B-H bonds that are made up of 45.36% from B with a hybridisation of 33.33%s + 66.67%p and 54.64% from H which is 100%s. Therefore, the splitting of electron density indicates that there are three sp3 hybridised orbitals on B that each interact with the sAO on an H atom. There is one lone-pair orbital made up of 100%s from B - this is unoccupied and so is the cause of the lewis acidity of the boron. There is also one other orbital made up of 100%s from B which is the 1s AO which is too low in energy to interact with the H AO's. If there were secondary orbital interactions these would also be shown in the log file but in this case there are none.

Vibrational analysis of Borane

When the energy of a molecule is optimised ideally gaussian has found the minimum ground state energy. However it is possible that the molecule is in fact a transition state and the way to check this is to use frequency analysis. For a maximum and minimum point the slope will be zero and so to tell them apart the second derivative of the function has to be investigated. The frequency analysis does this and shows the vibrations of the molecule. If all the vibrations are positive then the structure has been correctly optimised. This is because if the energy is at a minimum point energy needs to be put into the system for the vibration to occur (hence it has a positive energy). If one vibration is negative then it is at a transition state and if more than that are negative the optimisation has failed quite badly.

The published population can be found here

| Low frequencies cm-1 | -67 | -66 | -66 | -0.0019 | 0.0032 | 0.2123 |

| Real low frequencies cm-1 | 1144 | 1204 | 1204 |

The "low frequencies" of borane were found in the .log file and refer to the "-6" vibrational frequencies from the 3N-6 rule. These are the motions of the centre of mass and refer to the translational degrees of freedom that the molecule has. Ideally they should be zero but due to inaccuracies in the calculation very often deviate from this. The "real low frequencies" refers to the three lowest frequencies that should not be zero and ought to be a lot larger than the "low frequencies". In this calculation a very inaccurate basis set is used which is why some of the low frequencies are quite far from zero.

The calculated vibrations are shown in table 3:

All the vibrations are positive indicating that the reaction has been a success. There are 6 vibrations calculated which is as expected from the 3N-6 (where N= number of atoms)rule for a non-linear molecule. However when the IR spectrum is shown there are only three peaks on the spectrum. This is because vibrations 2 and 3 are degenerate and so show up as only one peak on the spectrum (at 1203.6 cm-1). Vibrations 5 and 6 are also degenerate and show up as one peak at 2737.44 cm-1. The peak at 1144.55 cm-1 is due to vibration 1. Vibration 4 is totally symmetric and so there is no change in dipole on the molecule and so this does not show up on the IR spectrum.

|

TlBr3

| Bond length | 2.65 Å |

| Bond Angle | 120.0o |

| Energy | -91.22 a.u. (2.395E5 kJ/mol) |

When running calculations on molecules containing heavy atoms such as Tl and Br it is important to use psuedo-potentials in the calculations. This is because heavy atoms show relativistic effects that cannot be recovered by the Schrödinger equation. It is also important to use a more accurate basis set than that used previously for optimising borane. The TlBr3 molecule was set very tightly for the D3h point group. It was optimised using the DFT-B3LYP method using the LanL2DZ basis set.This is a medium level basis set that uses the D95V basis set on first row elements and the Los alamos ECP on heavier elements. [2] It is very important that when running calculations that need to be compared that the same method and basis set are used. This is because the final energy is highly dependant on the method and basis set. After optimisation a summary of important information can be obtained in gaussview. The file type is .log, the calculation type is FOPT, the method is RB3LYP and the basis set is LANL2DZ. The molecule has charge=0, spin is singlet, the energy is -91.218 a.u, the dipole moment is ) debyes and the point group is D3h. The RMS gradient is 0.0000009 a.u. and the job took 20 seconds to run. The bond length and bond angle were measured. As expected the bond angle was 120o. The bond length was longer than in borane because the repulsion between the Br and Tl is greater than between B and H due to Br and Tl being bigger atoms. These values compare well to the literature values of 2.52Å and 120o[3].

The published population can be found here

| Low frequencies cm-1 | -3.4 | -0.0026 | -0.0004 | 0.0015 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Real low frequencies cm-1 | 46 | 46 | 52 |

A frequency analysis was carried out to ensure that the molecule had been optimised to the correct minima. All the vibrations were positive and so the optimisation was a success. There was the same number of vibrations as for borane because these molecules have the same symmetry. The "low frequencies" of the TlBr3 were found in the .log file and refer to the "-6" vibrational frequencies from the 3N-6 rule. These are the motions of the centre of mass and refer to the translational degrees of freedom that the molecule has. Ideally they should be zero but due to inaccuracies in the calculation very often deviate from this. The "real low frequencies" refers to the three lowest frequencies that should not be zero and ought to be a lot larger than the "low frequencies".

The published population can be found here

Gaussview has a list of what it considers to be suitable bond lengths and the bond will only appear if the distance is within these suitable parameters. It is possible to optimise a molecule so that the bond lengths are outside these parameters and the bonds "disappear" from gaussview. This is not important since to gaussview a bond is only a line drawn between two atoms whereas in real life a bond due to the attraction between atoms of opposite charges or of dipoles. A purely covelant bond leads to a build up of electron density between the atoms whereas a purely ionic bond leads to electrons from one atom attaching to another atom. In reality, most inorganic bonds will have some covalent and some ionic character with the proportions of each varying hugely between atoms.

Stereisomers of [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2]

Introduction

Complexes with a ML14L22 formula such as [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2] show cis/trans isomerism. The two mechanisms for the conversion between cis and trans isomers are dissociation and the Bailar twist. [4]Which isomer is most stable is affected by the nature of the ligands, the metal centre, and the temperature. IR is often a useful tool to determine which isomer is present as the differing symmetries of the isomers will give rise to different peaks in the IR spectrum. It is useful to use ligands such as CO which show strong peaks in the IR region. In this example, the two isomers of [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2] are investigated although in the calculations the phenyl rings have been replaced with chlorine atoms. This is because the phenyl rings are very large and the calculations would take too long to compute. Chlorine rings have a similar electronic contribution to the bonding and are also quite sterically large. [5] The two isomers are optimised and then a frequency analysis is carried out.

Optimisation

|

|

The optimisation of the isomers was carried out twice to give a greater accuracy of results. Firstly the two isomers were drawn out and the structures optimised using the B3LYP method and the LANL2MB basis set with the additional keywords "opt=loose". After the job was completed the P-Cl bonds had "disappeared" from gaussview indicating that the P-Cl bond length was outside the range that gaussian considers suitable for a bond. However this does not means that the bonds no longer exist - just that there isn't a neat line in gaussview indicating them.

The published population for the cis isomer can be found here and for the trans isomer can be found here.

Before the second optimisation took place the structures were modified according to the lab instructions so that the calculation would give the right minima. There are many possible rotamers of the complexes because of the rotation of the PCl3 group and optimisation of the "wrong" rotamer will give a false minima. For this reason, certain dihedral angles were set. In the cis isomer one chlorine atom was set so that it pointed up parallel to the axial bond (dihedral angle = 0o). A chlorine on the other PCl3 group was set so that it pointed down parallel to the axial bond (dihedral angle= 180o). In the trans isomer both PCl3 groups were set to an eclipsed conformation with one chlorine running parallel to one Mo-C bond. Both structures were then optimised as before but with the additional keywords "int=ultrafine scf=conver=9".

The published population for the cis isomer can be found here and the published population for the trans isomer can be found here

|

|

Comparing the energies for the first and second optimisation we can see that in both cases the final energy of the ground state comformation is lower after the second optimisation as expected. The trans isomer is very slightly lower than the cis isomer before and after optimisation but this is a very small energy difference and is alomst negligable 2.73 kJ mol-1. In the literature the energy difference between cis and trans is 72.98 kJ mol-1 [6] but this is for the complexes with the PPh3 ligands instead of the PCl3 ligands. This energy difference is probably because the PPh3 are much more bulky and so the cis isomer is likely to to be much more unstable than the cis isomer with Cl ligands. The P-Mo bond distance for the cis isomer was measured in gaussview to be 2.512 Å which is shorter than the literature value of 2.58 Å [7]. The P-Mo bond distance for the trans isomer was measured to be 2.445 Å, again shorter than the literature value of 2.50 Å[7]. The P-Mo-P angle was measured to be 94. 16o in the cis isomer - less than the literature value of 104.6o[7]. The P-Mo-P bond angle in the trans complex was measured as 177.38, again less than the literature value of 180o[7]. These differences from the literature values can be explained by considering that the literature values are taken for molecules of [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2] whereas this calculation has been carried out on molecules of [MO(CO)4(PCl3)2]. The phenyl groups are more bulky than the chlorine groups and so the PPh3 will sit further away from the metal centre due to increased steric demand, increasing the P-Mo bond lengths. The PPh3 groups will also repel each other more than the PCl3 which increases the P-Mo-P bond angle. From comparing these calculations to literature values we can see that changing the nature of the ligand on the molecule affects the properties and the overall energy. Therefore, changing the ligands can potentially be a way for chemists to "fine-tune" which stereoisomer is more stable and predominantly forms. Increasing the bulkyness of the ligand will increase the stability of the trans isomer relative to the cis isomer as the bulky ligands will try to be as far apart as possible. Using electron donating ligands is likely to increase the stability of the cis isomer relative to the trans isomer. This is because of the trans effect, whereby electron donating ligands trans to a carbonyl increases the back-bonding on the carbonyl and strengthening the CO-metal bond, stabilising the whole complex. In the trans isomer the electron donating ligands will be trans to each other and so this will have little effect on the overall stability.

Vibrational Analysis

The frequency analysis was carried out to ensure that both the isomers were correctly optimised and to compare the IR spectra of the isomers. It was computed with the same basis set and method and additional keywords and the previous optimisation.

The published population for the cis isomer can be found here and for the trans isomer can be found here.

| Trans somer | frequency cm-1 | intensity | cis isomer | frequency cm-1 | intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4 | 0.09 |  |

11 | 0.03 |

|

6 | 0.00 |  |

18 | 0.01 |

|

37 | 0.42 |  |

42 | 0.00 |

Looking at the C=O stretches is a good way to differentiate between the isomers as they show up well on the IR spectrum and the cis isomer will show more stretches than the trans isomer as the trans isomer is more symmetric.

| Symmetry | Calculated frequency/ cm -1 | Intensity | Literature frequency [MO(CO)4(PCl3)2][8] | Literature frequency [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2][9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b2 | 1945 | 763 | 1986 | 1897 |

| b2 | 1949 | 1498 | 1994 | 1908 |

| a1 | 1958 | 633 | 2004 | 1927 |

| a1 | 2023 | 598 | 2072 | 2023 |

| Symmetry | Calculated frequency/ cm -1 | Intensity | Literature frequency [MO(CO)4(PCl3)2][8] | Literature frequency [MO(CO)4(PPh3)2][9] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eu | 1950 | 1475 | 1896 | 1902 |

| eu | 1951 | 1467 | 1896 | 1908 |

| b1g | 1977 | 0.67 | n/a | n/a |

| a1g | 2031 | 4 | n/a | n/a |

The cis isomer has C2v symmetry whilst the trans isomer has D 4h symmetry and so the trans isomer has a higher symmetry. The literature predicts that there will be one C=O stretches seen on the IR spectrum for the trans isomer and four C=O stretches for the cis isomer and this is indeed the case with the computed spectra. There are two C=O stretches that are of observable intensity in the trans spectra but they are virtually degenerate and show up as one peak. The literature values for the [MO(CO)4(PCl3)2] C=O stretches are somewhat different from the computed stretches. In the cis isomer the computed stretches are around 50 cm-1 below the literature values whereas in the trans isomer the computed stretches are around 50 cm-1 larger than the literature values. The position of the C=O peak in the IR depends upon the bond strength which in turn depends upon the amount of back-bonding into the C=O π* anti-bonding orbital. This is affected by the nature of the ligands trans to each C=O on the complex. In the trans-[MO(CO)4(PCl3)2] isomer the PCl3 groups are trans to one another and so changing the PCl3 groups for PPh3 groups will have a small affect on the C=O backbonding. This is why there is only a small difference between the frequencies of the C=O stretches in the trans-[MO(CO)4(PCl3)2] and trans-[MO(CO)4(PPh3)2] complexes. In the cis isomer two of the C=O groups are trans to PCl3 groups and so changing them to PPh3 groups has a larger affect on the C=O backbonding. The difference in frequency for the C=O stretches between cis-[MO(CO)4(PCl3)2] and cis-[MO(CO)4(PPh3)2] complexes is much larger (around 100 cm-1 for the largest change).

|

|

Mini Project: PF3 and it's hypervalent analogues - PF5 and PF6-1

Introduction

|

|

A molecule is said to be hypervalent if it contains one or more main group elements which violates the octect rule i.e. has more than 8 electrons in its outer shell. The exact nature of hypervalency has been the subject of debate for some time, and even its very existence in the subject of some debate [10].Examples of hypervalent include penta- and hexacoordinated phosphorus, silicon and sulphur compounds. In this project the structure of PF3 will be compared to the structures of the hypervalent PF5 and PF6 molecules to investigate the effect of hypervalency. PF3 has a pyramidal trigonal structure (C3v) with lone pair at the apex and 8 electrons in the valence orbital of phosphorus. PF5 has a pentagonal pyramidal structure (D3h) with 10 electrons in the phosphorus valence orbital. PF6 has an octahedral structure (Oh) with 12 electrons in the phosphorus valence bond.

Two different MO models have been proposed to try and explain hypervalency in molecules such as these. Firstly, the involvement of d-AO's leading to hybrid orbitals such as sp3d2 orbitals and secondly the formation of three-centre, four-electron bonds without significant d-AO contribution[11]. These types of bonds can be pictorially represented by linearly combining three atomic orbitals. In Valence Bond theory mesomerism is used to represent hypervalency assigning some bonds as ionic and some as covalent to arrive at the correct number of electrons. This is the actually just another way of representing 3c-4e bonds. In this example the two axial bonds are taken to each be the "average" of a covelant bond and an ionic bond.

|

The aims of this Mini Project are to:

- 1) Investigate the structural differences between PF3, PF5 and PF6 and explore the mesomeric picture of PF5.

- 2) Examine the Molecular Orbitals and vibrations of PF3.

- 3) Examine the NBO's of PF5 and PF6 to explore the possibility of d-orbital contribution leading to hybrid orbitals.

The structures of PF3, PF5 and PF6

All the structures were optimised using the DFT B3LYP method and the 6-311G basis set. The population analysis can be found here (PF3), here (PF5) and here (PF6).

| F-P Bond length | 1.74Å |

| F-P-F Bond Angle | 96.7o |

| Dipole moment | -2.88 Debye |

| Energy | -640.96 a.u./ -1.683E6 kJ/mol |

| Fax-P bond length | 1.70Å |

| Fax-P bond length | 1.67Å |

| Fax-P-Fax Bond Angle | 180.0o |

| Fax-P-Feq Bond Angle | 90.0o |

| Feq-P-Feq Bond Angle | 120.0o |

| Dipole moment | 0.00 Debye |

| Energy | -840.63 a.u./ 2.207E6 kJ/mol |

It is interesting to note that there is not a significant change on the calculated bond lengths of the three molecules. The values of for the bond length of PF3molecule does not correspond to well with the experimentally determined value of 1.57Å [12] but does correspond well with the experimentally determined angle 97.8o[13]. Even more accurate computational methods such as B3LYP/DZP++ still overestimate the bond length to be 1.621[14]. It is likely that very high levels of basis sets are needed to get a very accurate bond length. The bond lengths for the PF5 molecule are also seen to be an overestimate when compared to the literature values (Fax-P bond length=1.58Å, Fax-P bond length= 1.53Å)[15]. Similarly, the calculated bond lengths for PF6 are an overestimate of the experimental bond lengths of around 1.614Å[16] but in this case the experimental values must not be taken too literally as they are of the PF6 ionically bound and not in its free state.

| F-P Bond length | 1.71Å |

| F-P-F Bond Angle | 96.7o |

| Dipole moment | -0.00 Debye |

| Energy | -940.67 a.u./ -2.270E6 kJ/mol |

|} Looking at the calculated bond lengths it is possible to hypothesize whether the mesomeric picture in fig 14 is an accurate picture of the structure of PF5. In this bonding picture the equatorial bonds are formed from sp2 orbitals on phosphorus and an appropriate orbital on fluorine. The axial bonds are formed from a 3c-4e-type bond as represented in fig 13 with two electrons in the bonding orbital and two electrons in the non-bonding orbital. This is equivalent to the axial bonds being "half-bonds" and is essentially a combination of two resonance forms. If this were the case, then it would be expected that the axial P-F bonds would be a lot longer than the equatorial P-F bonds [17]. However, there is not a huge difference between either the calculated or the experimental bond lengths of the axial and equatorial bonds. This indicates that this picture of the axial bonding is not strictly accurate. It is in fact, a lot more accurate to consider a structure in which any of the fluorines, including the equatorial ones, can resonate in this way.[18].

The molecular orbitals of PF3

An "energy" calculation was run for the molecules using the same basis set and method as before but with the keywords "pop-full" added and with the "full NBO" option enabled. This allowed the MO's to be computed. The valence orbitals as well as the two degenerate LUMO orbitals are shown in table 15 below.

The published population analysis: PF3, PF5, PF6.

The 2a1 and 2e orbitals have antibonding character[19] For 2a1 the main contribution is from p-orbitals on the phosphorus and for 2e the main contribution is from p-orbitals on the fluorine. The four orbitals above them (3a1, 3e, 4e and 1a2) are all due to the 2p lone pairs on the fluorine. 4e, 3e and 1a2 are non-bonding orbitals and so do not overlap with any phosphorus orbitals although the 3e orbitals show some overlap between the AO's on neighbouring fluorines. The 3a1 orbital bonding and looks as if it has some Pi double bond character. The 4a1 HOMO orbital is mainly due to the lone pair on the phosphorus although there is some anti-bonding interaction with 2p orbitals on the fluorine's. This is why molecules of PF3 react readily with lewis bases to form products such as PF3O.

It is possible to compare these molecular orbitals to the hypothetical pyramidal BH3 molecule (see fig 15). The obvious differences arise because P and F have many more AO's, i.e. the valence AO's on hydrogen are s-orbitals whilst of fluorine they are p-orbitals. However, there are some similarities between them. Interestingly the HOMO PF3 looks reasonably similar to the LUMO of the BH3 although on PF3 there is an antibonding interaction between p-orbitals on the fluorine and the Pz on the phosphorus whereas on BH3 this orbital shows a bonding interaction (mixing) between the S-orbitals on the hydrogen and the Pz on the boron. The degenerate LUMO PF3 orbitals involve anti-bonding interactions between the Px and Py phosphorus orbitals and p fluorine orbitals whereas the degenerate BH3 LUMO+1 involve anti-bonding interactions between the Px and Py boron orbitals and s hydrogen orbitals. Other than that the MO's are quite different mainly because the rest of the orbitals close to the HOMO in PF3 are mainly due to the lone pairs on the fluorine's.

|

The vibrational analysis of PF3

The frequency calculations for all three molecules were run to ensure that the structures were at a mimima.The calculations were run using the same basis set and method as before but with "pop=(full,nbo)" in the additional keywords section. The frequencies were examined and all were found to be positive indicating that the structure was correctly minimised. Table 16 shows the vibrations of PF3.

The published population analysis: PF3, PF5 and PF6.

The C3v is a lower order of symmetry than the D3h point group and so the vibrations for PF3 are a lot less symmetric than those for BH3. Hence, all of the vibrations appear as individual peaks in the IR spectrum of PF3.

|

The NBO's of PF3, PF5 and PF6

The NBO's of the molecules were taken from the output files from the MO calculations. Fig 16 shows the relative charges (in Debyes) of each atom in the three structures. In all cases the phosphorus is strongly lewis acidic, more so in PF5 and PF6. The fluorine atoms are negative and of similar values in all of the molecules although most negative in PF6. Fluorine is the most electronegative element (3.98 on the Pauling scale) and phosphorus is a lot less electronegative (2.19). This is because phosphorus is a larger atom with much more diffuse atomic orbitals and is a lot easier to polarize. Hence it makes sense that the fluorines are negative as they pull electron density away from the phosphorus towards them.

| PF3 | PF6 | PF6 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| P=1.370D, F=-0.457D | P=1.925 Feq=-0.376D, Fax=-0.399D | P=1.884D F=-0.481D |

One of the suggested models for hypervalency states that the octect rule is not violated in hypervalent molecules due to the presence of hybrid orbitals with a significant contribution from d-orbitals (eg sp3d2). These hybrid orbitals allow "extra" orbitals to account for the extra electrons. NBO analysis allowed us to test out this model - for it to be correct there would have to be valence bonding orbitals with a significant contribution from d-orbitals.

When the orbital contributions to bonding for PF5 were examined it was discovered that most of the orbitals close to the HOMO level were made up of lone pairs with no contribution from d-orbitals. In fact, there were no bonding orbitals in the molecule with contributions from d-orbitals so for PF5 this model is obviously not correct. The NBO analysis of PF6 told a similar story. Again, most of the molecular orbitals near the HOMO were made up from lone pairs on the fluorines and there were no bonding orbitals with significant contributions from d-orbitals. Clearly, for these two molecules at least, this model of hypervalency is not correct. Therefore, it can be concluded that the mesomeric picture of hypervalency is much closer to what is actually happening within the molecule. The relatively large size of the phosphorus atom and so the reduced steric hindrance between fluorines and the higher polarizability of phosphorus allows this this to happen. For PF5 it is unlikely that specific fluorines (i.e. the axial ones) take part in 3-centre, 4-electron bonds and much more likely that any of the fluorines can take part in a similar sort of bonding. Certainly, electron-rich multicentre bonds are a much closer to reality than d-orbital hybrids[20]but the exact nature of these bonds is difficult to determine.

Conclusion

In conclusion these computational methods have been very good at predicting the bond and properties of inorganic molecules with good agreement with experimental data. A few differences do arise such as the bond lengths of P-F which are predicted to be longer than experimental data shows them too be. However, on the whole the agreement is good and it is easy to see that computational methods will soon become invaluable when conducting experiments.

References

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/5b_nbo_analysis.html

- ↑ http://www.huntresearchgroup.org.uk/teaching/teaching_comp_lab_year3/4b_creating_bcl3.html

- ↑ J. Blixt, J. Glaser, J. Mink, I. Persson, P. Persson and M. Sandtroem, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117 (18), pp 5089-5104

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14-17. DOI:10.1021/ic50191a003

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "bond" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 ELmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 3864-3873

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kemp, Inorg. Chem, 1978, 17, 2680.

- ↑ Gillespie, R. J.; Silvi, B. The octet rule and hypervalence: two misunderstood concepts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 233-234, 53-62 [2]

- ↑ W. Kutzelnigg, Angewandte Chemie 1984 Volume 23,pages 272–295 [3]

- ↑ J.H. Callomon, E. Hirota, K. Kuchitsu, W.J. Lafferty, A.G. Maki and C.S. Pote In: K.H. Hellwege and A.M. Hellwege, Editors, Structure Data of Free Polyatomic MoleculesLandolt-Börnstein, New Series II vol. 7, Springer, Berlin (1976)

- ↑ J.H. Callomon, E. Hirota, K. Kuchitsu, W.J. Lafferty, A.G. Maki and C.S. Pote In: K.H. Hellwege and A.M. Hellwege, Editors, Structure Data of Free Polyatomic MoleculesLandolt-Börnstein, New Series II vol. 7, Springer, Berlin (1976)

- ↑ J. Moc, Chem. Phys. Letters, 363, 2002, Pages 328-336 [doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(02)01212-5]

- ↑ H. Kurimura, S. Yamamoto1, T. Egawa, K. Kuchitsu, Coord. Chem. Rev., 233-234, 2002, p53-62 [4]

- ↑ S.H. Kim et al.,Current Applied Physics 4 (2004) 452–454[5]

- ↑ R. Gillespie, B. SilvibCoor, Chem. Rev., Volumes 233-234, 1 November 2002, Pages 53-62 [6]

- ↑ Third year Inorganic lecture course, Main Group Chemistry, D. Scheschkewitz

- ↑ A. Jürgensen, R. G. Cavell, Journal of Electron Spectroscopy and Related Phenomena, 128, Issues 2-3, 2003, Pages 245-260 [7]

- ↑ W. Kutzelnigg, Angewandte Chemie 1984 Volume 23,pages 272–295 [8]