Rep:Mod2:cl308

Module 2: Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital)

Introduction

This module concerns the applications of computational modelling in inorganic chemistry. Specifically, density functional molecular orbital techniques are used to accurately optimise the geometry and calculate various properties of molecules such as molecular orbitals and vibrational frequencies. Once these have been calculated it is then possible to evaluate the techniques by comparing them to actual literature values.

BH3 Analysis

Optimisation of BH3

Initially, the task was to learn the basics of the GaussView 5.0 software. Borane was drawn and the B-H bond lengths were noted as being 1.18Å, all the B-H bonds were lengthened to 1.50Å. The molecule was optimised using the DFT/B3LYP method and a basis set approximation of 3-21G. This produced a log file that has been uploaded into D-space.

XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7

The results of the optimisation report that the B-H bond length was 1.19Å with an angle of 120.0o, which corresponds to trigonal planar geometry (Table 1.1), which corresponds well with the literature[1].

| Optimised Borane | ||

| Bond Length/Å | 1.19 | |

| Bond Angle/o | 120.0 | |

| Energy/a.u | -26.462 | |

It is important to check that the molecule has been fully optimised, which was done by examining the ".out" file. This states that the parameters are beneath threshold values and that the optimisation is complete. There is also the graphical representation of this (Figure 2 & 3).

|

|

The initial structure is changed to mitigate against any inequality in attractive or repulsive forces resulting in a more stable geometry. Each successive step reduces the energy of the molecule and the gradient converges to zero. At this point the stable state equilibrium position is obtained and there are no net forces (e.g nuclear-nuclear repulsion, nuclear-electron attraction or electron-electron interactions) acting on the molecule.

Calculating the Molecular Orbitals of BH3

The BH3 molecule from the prior optimisation was submitted to SCAN to analyse the molecular orbitals using Gaussian with a more rigorous basis set (6-31G). The output file was posted on the D-space.

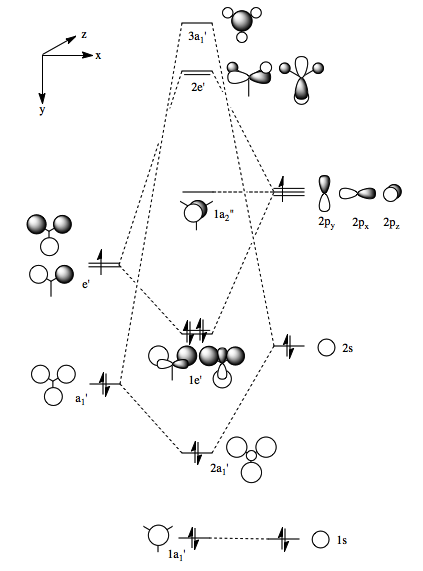

The computed orbitals are in good agreement with the one's from a LCAO approach (Figure 4).

| Calculated Molecular Orbitals of Borane DOI:10042/to-7873 | |||||||||

| GaussView Representation |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Symmetry Label | 1a1' | 2a1' | 1e' | 1e' | 1a2" | 2e' | 2e' | 3a1' | |

| Energy/a.u | -6.77 | -0.515 | -0.353 | -0.353 | -0.068 | 0.180 | 0.180 | 0.166 | |

The computed molecular orbitals shown in Table 1.2 and the orbitals shown in Figure 4, which are obtained from the LCAO approach generally show good conformity both in terms of shape and relative energies. The advantage of the computer generated molecular orbitals is that it gives a good picture of the orbital as a whole making it easier to visualise what the orbital might actually look like. The 1e' orbitals are found to be degenerate as shown by their respective energies, as are the 2e' orbitals. However, there are some inconsistencies within the results of the higher energy unoccupied molecular orbitals. In the computed molecular orbitals the degenerate 2e' orbitals are found to be higher in energy than the 3a1' orbital, which is not the case in the LCAO molecular orbital diagram. It is hard to qualitatively decide between the s-s interaction and the s-p interaction as to which is stronger. As a result, it is difficult to correctly order these molecular orbitals. From the computed results that show the 2e' to be higher in energy and it is fair to say that the s-s interactions are greater than the s-p interactions.

Natural bond orbital analysis was also carried out so that the charge density across the borane molecule could be investigated. Figure 5 clearly shows the boron atom to have a partial positive charge of 0.278D, whilst each of the hydrogen atoms have a partial negative charge of -0.093D. The boron shows a slight positive charge due to it being more electropositive than the hydrogen atoms, which indicates that BH3 is a lewis acid, capable of accepting electrons to the boron atom.

On examining the file, it is possible to see the individual contributions to a B-H bond. The boron contributes 44.48% of the electron density, whilst the remaining 55.52% come from a hydrogen. It is also possible to figure out the hybridisation of the boron from the ratio of s and p orbtial contributions. Since the ratio of s:p is 1:2, the boron atom is sp2 hybridised. From the file secondary orbital interactions could be obtained, which would show whether any substantial mixing of the molecular orbitals has occured. However, in this case the energies are all small and so no substantial mixing occured.

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The vibrations of BH3 were calculated from the optimised BH3. This was done to ensure that the optimised structure proposed is a minimum, rather than a maximum (which would suggest it to be a transition state). This is done by investigating the second derivative of the potential energy surface, if the frequencies for the vibrations are all positive then the optimised structure is correct and the point is a minimum. The results and animations of the vibrations are in Table 1.3.

The frequencies are reported to the nearest wavenumber because of an inherent systematic error with the method used. This is due to a harmonic approximation being used for vibrations that are actually anharmonic. Intensities are rounded to the nearest whole number because of convention.

There are six recorded vibrations, as predicted by the 3N-6 rule for non-linear molecules. The IR spectrum (Figure 6) only shows three peaks (1144cm-1, 1204cm-1, 2737cm-1), which have been assigned to their respective vibrations in Table 1.3. This can be explained by the doubly degenerate vibrations (1204cm-1, 2737cm-1), which means that for each doubly degenerate vibration there is only one peak since the vibration frequencies overlap. The peak at 2598cm-1 is also absent because it is not an IR active vibration (intensity of 0) due to it being a completely symmetric vibration and therefore exhibits no change in dipole moment.

The frequency analysis also reported the low frequency data, which was due to translation of the molecule rather than bond distortion. These were -66.7625cm-1, -66.3592cm-1, -66.3589cm-1, -0.0020cm-1, 0.0031cm-1, 0.2123cm-1. Ideally these low frequencies would be as close to zero, which in the main they are. The deviations observed can be explained by the small basis set used but there is still a large difference of a couple of orders of magnitude between these frequencies and the real frequencies, which shows that the results obtained are good and that the basis set is suitable.

TlBr3 Analysis

Media:TlBr3.out TlBr3 was drawn in GaussView and the symmetry was restricted to D3h with a very tight tolerance. The molecule was then optimised using B3LYP with a LanL2DZ basis set. This basis set is slightly different from the one used with borane because of the heavier elements within the molecule, which have more complex electronic structures. The LanL2DZ basis set relies on the fact that the inner electrons are considered to be a pseudo-potential, whilst the valence electrons are used. Despite the approximations used, good results for the optimisation are still obtained.

| Optimized TlBr3 | Computed Value XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7 | Literature Value[2] |

| Bond Length/Å | 2.65 | 2.52 |

| Bond Angle/ᵒ | 120 | 120 |

| Energy/a.u. | -91.22 | - |

The next step was to carry out vibrational analysis on the TlBr3 to ensure that a true minimum has been reached. As previously mentioned, the way in which the structure is verified to be optimised to a minimum is by calculating the second derivative of the potential energy surface of the molecule. Running vibrational analysis also creates an IR spectrum that can be compared to experimental results. The same basis set was used as the optimisation because the basis set determines the accuracy of the potential surface and so it is essential that the basis set is the same, enabling comparison.

The results were examined and the file was uploaded to the D space. Firstly the low frequencies were inspected (Table 1.6), which all appeared to have values very close to zero. This suggested that the calculation was successful.

| Optimized TlBr3 low frequencies/cm-1 |

| -2.7110 |

| -0.0002 |

| -0.0001 |

| 0.0001 |

| 1.1507 |

| 4.1778 |

Secondly, the real frequencies were examined and all of them appeared positive, which is indicative of the optimisation working well and finding a minimum on the potential energy plot. Since the molecule is non-linear by the 3N-6 rule it is expected that there are six vibrational modes (Table 1.7), which is the case.

| Optimized TlBr3 real frequencies/cm-1 | ||

| frequency/cm-1 | intensity | |

| 46 | 4 | |

| 46 | 4 | |

| 52 | 6 | |

| 165 | 0 | |

| 210 | 25 | |

| 210 | 25 | |

As was the case with the borane, there are only three visible vibrational peaks in the IR (Figure 6) because of two cases being degenerate vibrations and there being an IR inactive vibration (intensity=0).

Stereoisomers of [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] DOI:10042/to-7861 DOI:10042/to-7862

Introduction

This section concerns the stereoisomers of Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2. Ideally, it would be possible to use Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 in the calculations but due to the large number of atoms in the phenyl groups it would be too demanding computationally to run in a reasonable time. For this reason chlorine atoms were used instead of phenyl groups, whose computational demand is substantially less. Further to this, it is expected that they would exhibit similar electronic contributions to bonding as the phenyl groups since they are sterically quite large.

Optimisation

Initially the isomers were optimised using a low-level basis set, LANL2MB, which quickly found a structure close to the optimised energy minimum. The bonds between the phosphorus atoms and the choline atoms had seemingly disappeared but this was attributed to the fact that the bond length was outside the value recognised by GaussView and so were ignored. DOI:10042/to-7863 DOI:10042/to-7864

These bonds were redrawn and the geometry of the molecules was altered slightly to produce rationally lower energy conformers, which were set up to be run in a slightly larger basis set. The alterations made were that in the cis stereoisomer one P-Cl bond was placed axial to a Mo-C bond and on the other phosphorus atom another P-Cl bond was made to point downwards. The resulting torsion for the P-Cl bond that was synperiplanar was 0°, whilst the other, antiperiplanar, P-Cl bond showed a torsion of 180°. The alterations made to the trans stereoisomer were to make the PCl3 groups eclipse each other but yet ensuring that one of the P-Cl bonds on each of the phosphorus atoms had a torsion with the same Mo-C bond of 0°. These changes were performed so as to ensure that a false minimum was not obtained and that in fact a global minimum had been reached for each isomer rather than just a local minimum on the potential energy surface. DOI:10042/to-7867 DOI:10042/to-7873

These altered molecules were then subjected to another optimisation using the DFT-B3lYP method, a LANL2-DZ basis set and ultrafine electronic convergence. This was chosen because of the larger basis set with an accurate pseudo-potential suitable for heavier atoms.

| - | Optimization 1 Trans | Optimization 1 Cis | Optimization 2 Trans | Optimization 2 Cis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2MB | LANL2MB | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ |

| Energy/a.u. | -617.52211667 | -617.52510219 | -623.5760309 | -623.5771 |

| RMS Gradient Norm/a.u. | 0.00006228 | 0.00000590 | 0.00005594 | 0.00001373 |

| Dipole Moment/D | 0.1343 | 8.6261 | 0.071 | 1.3125 |

| JMol file | XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7 | XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7 | XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7 | XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7 |

Once the molecules had been optimised again it was possible to see that the second optimisation had produced lower energy optimisations for both molecules. The comparison between the second optimisation energy values for each stereoisomer showed that there was only a small difference between them. This does not agree well with the literature of P(Ph)3 substituents where there is a reported difference of 72.98 kJmol-1 between the stereoisomers. Whilst it is difficult to draw any conclusions between this inconsistency because the molecules in question are different, it is possible to say that one source of the difference could be attributed to the substantially bulkier P(Ph)3 ligands. The calculated difference between the energies of the cis and trans isomers (Table 1.8) is approximately 3kJmol-1, but this has little reliability since the error associated with recording the energy is roughly 10kJmol-1. As a result, it is difficult to say with confidence which isomer is the most stable.

From the literature it has been found that the trans is the lower energy, thermodynamic, product owing to differing dipole moments are steric factors. However, from the calculated results the dipole moment is lower in the trans isomer compared to the cis isomer and the steric bulk of the large PCl3 groups are as far away as possible in the trans arrangement. Conclusions can be drawn from this such that by increasing the electronegativity of the substituents the trans isomer can be favoured due to the lower dipole moment. Also, bulkier substituents favour the trans isomer because it reduces steric strain compared to the cis isomer.

Further analysis can be performed using GaussView on the optimised structures (Table 1.9 and Table 1.10). Examining the results for the cis isomer first (Table 1.9) it is clear that there is generally good agreement with the literature. The bond lengths show a good consistency with the literature values. The bond angles show a slight deviation from the literature results and this could be due to the differing steric bulk of the PCl3 groups compared to the PPh3 groups. However, there could equally be an error with the computational method and specifically the basis set chosen. A solution to this would be to use a larger basis set, which had a better pseudo-potential but this would take a longer time to process.

| cis [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] | literature[3] cis [Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] | |

| average Mo-P bond length / Å | 2.51 | 2.58 |

| Mo-C bond length / Å | 2.01 & 2.06 | 1.97 & 2.04 |

| P-Mo-P bond angle / ° | 94.2 | 104.6 |

| P-Mo-C bond angle/° | 176.1 | 163.7 |

| P-Mo-C bond angle/° | 89.4 | 80.6 |

Table 1.10 shows the trans isomer's measurements. These are in good agreement with the literature results.

| trans [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] | literature results | |

| P-Mo bond length/Å | 2.44 | 2.50 |

| Mo-C bond length/Å | 2.06 | 2.01 |

| P-Mo-P bond angle/° | 177.4 | 180.0 |

| P-Mo-C bond angle/° | 90.0 | 89.5 |

Comparing the results of the two stereoisomers showed that the Mo-P bond length was shorter in the trans isomer, which can be explained by the fact that the bond is lengthened in the cis stereoisomer to reduce repulsive interactions between the two adjacent PCl3 groups.

Frequency Analysis

Frequency analysis using GaussView was performed to ensure that the optimised structures were minima. It was observed that all the real frequencies were positive vaues thus signalling that the optimisations had worked and indeed found minima on the potential energy surfaces. The same basis set, LANL2DZ, was used in the frequency analysis as the final optimisation so that comparisons could be drawn between the energies.

It was noticed that there were certain low frequency vibrations, which

| Carbonyl Vibrations of trans-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] | |||||

| Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry Label | Literature Frequency

[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]/cm-1[4] || Literature Frequency [Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2]/cm-1 | |

|

1950 | 1475 | Eu | 1896 | 1902 |

|

1950.83 | 1466 | Eu | 1896 | 1908 |

|

1977 | 1 | B1g | - | - |

|

2031 | 4 | A1g | - | - |

| Carbonyl Vibrations of cis-[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] | |||||

| Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | Symmetry Label | Literature Frequency

[Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2]/cm-1>[5] |

Literature Frequency

[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2]/cm-1 |

|

1945 | 764 | B1 | 1986 | 1897 |

|

1949 | 1497 | B2 | 1994 | 1908 |

|

1958 | 631 | A1 | 2004 | 1927 |

|

2023 | 599 | A1 | 2072 | 2023 |

|

|

The cis isomer has four stretches corresponding to the carbonyl bonds, whilst the trans isomer only has two. This results from the difference in symmetry between the two different geometries where the cis is C2v and the trans is D4h. In the calculated spectra, four peaks are seen for the cis isomer as expected but four frequencies are also observed for the trans complex. This can be explained by the symmetry of the trans isomer: two of the carbonyl stretches will be degenerate but in the cis isomer, these two stretches are not chemically equivalent so will result in two individual frequencies.

Mini Project

Introduction

The purpose is to investigate and compare isoelectronic and isostructral compounds of benzene. In so doing it is hoped that a greater understanding of the electron distribution, vibrations and molecular orbitals of these molecules, especially borazine and other hexa-membered rings containing alternating Gp III and Gp V atoms. Hopefully, it will be possible to draw trends from the observed results as the groups are descended.

Benzene DOI:10042/to-7860

XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7

Initially benzene was drawn in GaussView and optimised using a DFT-B3LYP method with a 3-21G basis set. This basis set was chosen because of the relatively small computational demand whilst investigating simple molecules to a suitable level of accuracy. the optimisation showed that the molecule was planar with uniform C-C bond lengths and bond angles Table 2.1, which also compared well with literature values.

| Optimised Benzene | ||

| Bond Length/Å | 1.40 | |

| Bond Angle/o | 120.0 | |

| Energy/a.u | -230.98 | |

The next stage was to use this optimised molecule to find the vibrations of benzene, which also confirmed that indeed an optimised minimum had been found due to all the vibrational frequencies being positive and larger than the low frequencies, whose frequencies were all near zero. Some key vibrations are shown in Table 2.2.

| Vibrations of Benzene | ||||||

| Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | ||||

|

697 | 118 | ||||

|

1015 | 0 | ||||

|

1064 | 0 | ||||

|

1068 | 4 | ||||

|

1069 | 4 | ||||

|

1540 | 12 | ||||

|

1540 | 12 | ||||

|

3212 | 34 | ||||

|

3212 | 34 | ||||

The vibrations listed above are the main vibrations exhibited by benzene, some of these have intensities of zero which can be explained by the fact that they are symmetric and have no dipole moment and hence are not IR active. These vibrations can be compared with the vibrations of other molecules. the IR spectrum of benzene can be found in Figure 9.

The next stage was to investigate the molecular obritals of benzene, which was done using GaussView - full NBO was selected under the NBO tab and the additional keywords 'pop=full' were also inserted. The calculated molecular oribtals of benzene agree well with the qualitative LCAO appraoch since there are two sets of two degenerate orbitals, being the HOMOs and LUMOs respecitvely.

| Calculated Molecular Orbitals of Benzene | |||||||

| GaussView Representation |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Energy/a.u | -0.346 | -0.251 | -0.251 | 0.0053 | 0.0053 | 0.107 | |

It is also noted that in the calculated orbitals there is a high level of symmetry observed (C2). The final step was to investigate the charge distribution of the molecule by looking at the NBO data (Figure 10).

From the .log file it is possible to see that the carbons have a partial negative charge, which is matched by the partial positive charge on the hydrogens.

Borazine DOI:10042/to-7856

XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7

Borazine is isoelectronic and isostructral with benzene (Figure 11). The molecule was drawn and optimised using GaussView and as before a DFT-B3LYP method with a 3-21G basis set was employed. Despite being isoelectronic, nitrogen has one more and boron one less electron than carbon meaning that there should be observable differences.

| Optimised Borazine | ||

| Bond Length/Å | 1.45 | |

| Bond Angle/o | 117.0 & 123.0 | |

| Energy/a.u | -241.357 | |

From Table 2.4 it is clear that the bonds within the ring are slightly longer than those observed in benzene. The bond anagle B-N-B is slightly larger than the expected 120o, whilst the N-B-N angle is slightly less than the expected 120o. This observation can be explained by the fact that despite the delocalisation, the electronegativity of nitrogen draws marginally more electron density towards it, which forces the bond angle to open slightly because of electron repulsion. The N-H bond length is 1.019Å, which is shorter than the boron hydrogen bond (1.19Å). This is expected since nitrogen is more electronegative and hence draws the hydrogen closer.

The structure was then subjected to vibration frequency analysis using a DFT-B3LYP method with a 3-21G basis set. A selection of the important vibrations were recorded in Table 2.5.

| Vibrations of Borazine | ||||||

| Vibration | Frequency/cm-1 | Intensity | ||||

|

738 | 65 | ||||

|

948 | 0 | ||||

|

985 | 315 | ||||

|

1411 | 41 | ||||

|

1411 | 41 | ||||

|

1483 | 437 | ||||

|

1483 | 437 | ||||

|

2672 | 265 | ||||

|

2672 | 265 | ||||

The shorter, stronger bonds of N-H compared to those of benzene's C-H have a higher vibrational frequency. Due to the weaker, longer bonds of B-H when compared to C-H or N-H, there is an expected decrease in the frequency with the vibrations of B-H bonds.

The next step was to perform molecular orbital analysis and collect NBO data. This was done in the same manner as for benzene.

| Calculated Molecular Orbitals of Benzene | |||||||

| GaussView Representation |  |

|

|

|

|

| |

| Energy/a.u | -0.322 | -0.273 | -0.273 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.109 | |

It is clear that the molecular orbitals are not as symmetrical as the molecular orbitals of benzene. However, the orbitals generally have the same shape with the same planes of symmetry especially in the HOMO and LUMO. Due to the differing electronegativities of nitrogen and borane the molecular orbital lobes have been slightly distorted.

This difference in electronegativities can explain the charge distribution of the molecule (Figure 12). Because nitrogen is more electronegative than eith boron or carbon it has a partial negative charge, and as a result the hydrogens that are bonded to the nitrogen have a partial positive charge. The boron, which is slightly electropositive exhibits a slight positive charge and the hydrogens bonded to boron a show a slight negative charge.

Al3P3H6

This molecule was chosen because it could be used to see what happens when Gp III and Gp V are descended. Once optimised, the molecule is no longer planar.

XML error: Mismatched tag at line 7

| Optimised Al3P3H6 | ||

| Bond Length/Å | 2.30 | |

| Bond Angle/o | 111.8 & 128.3 | |

| Energy/a.u | -29.138 | |

References

- ↑ M. S. Schuurman, W. D. Allen, H. F. Schaefer, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2005, 26 (11), 1106 DOI:10.1002/jcc.20238

- ↑ J. Blixt, J. Glaser, J. Mink, I. Persson, P. Persson and M. Sandtroem, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117 (18), pp 5089-5104

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680-2682. DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kemp, Inorg. Chem, 1978, 17, 2680.

- ↑ ELmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 3864-3873