Rep:Mod2:ch1508

Module 2: Bonding (Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital)

Ciarán Healy, March 2011

Introduction

On this page, computantional methods are used to analyse the structure and bonding of various compounds. Gaussian/Gaussview software was used extensively to respectively calculate and visualise data (although from time to time, raw text files require examination and alteration). Techniques including geometry optimisation, NBO and MO analysis and vibrational analysis. Different basis sets, giving different levels of accuracy can be used depending upon the requirements of the calculation (accuracy vs. time).

BH3

Optimisation

The simple borane BH3 was drawn in Gaussview with a trigonal planar structure, all bonds were set to a uniform length of 1.50Å. This structure was used to proved a starting point for the forthcoming optimisation. The molecule was optimised using the B3LYP method with a 3-21G basis set. The calculations that are used to carry out this process utilise the Born-Oppenheimer approximation (fixed nuclei, with only the electrons moving). The position of the nuclei is then varied, and the Schrödinger equation solved to give the energy. The calculation works by looking for the minimum in the potential energy surface. The nuclei are moved until the energy reaches a its lowest point. The process produced the following .log file:

.log file from borane optimisation

The optimisation gave a geometry with the expected 120° bond angles, the bond lengths were determined to be 1.19Å. The button below links to a jmol of the molecule.

The progress of the optimisation can be seen in the following images depicting the intermediate geometries, starting from step 1 (the initial geometry drawn in Gaussview), and progressing to step 5 (the final optimised geometry).

|

|

|

|

|

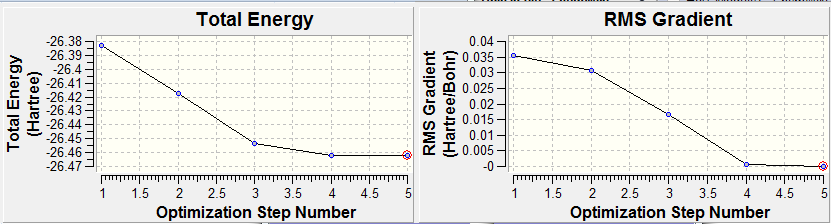

The graphs below show the progress of the optimisation, in terms of the energy and the gradient of the energy for each step.

The final energy of the molecule was -26.462 a.u., it can also been seen that the gradient is tending towards zero at the final step, this is reinforced by looking at the last two geometries (step 4 and step 5), which are very similar.

Frequency Analysis

Files from frequency analysis.

Gaussian can be used to compute the vibrational frequencies of the molecule, and to generate a proposed IR spectrum.

Aside from the benefits in seeing how the molecule vibrates (this can be visualised), frequency analysis can be used to check that the optimisation carried out above has been properly completed. We should expect to see no 'imaginary' vibrational frequencies (those with a wavenumber value of less than zero). A negative frequency can indicate a transition state, more than one suggests that the optimisation has not worked properly. In practice, slightly negative values can simply be caused.

One particular area where we can expect to see some errors is for high energy vibrations, this is due to the fact that the model being used assumes harmonic oscillation, and thus does not account for some anharmonic vibrations.

To preserve the integrity of the calculations for this stage of the procedure, it is important that the same basis set as was used for the optimisation is used again.

| Freq/cm-1 | Intensity | Vibration | Description | Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1146 | 93 | Wag | A" | |

| 1205 | 12 | Bend(Scissor) | E' | |

| 1205 | 12 | Bend(Rock) | E' | |

| 2593 | 0 | Symmetric Stretch | A' | |

| 2731 | 104 | Asymmetric Stretch | E' | |

| 2731 | 104 | Asymmetric Stretch | E' |

One thing that is immediately obvious when comparing the vibrational data and the spectrum is an apparent disagreement between the number of vibrations listed, and the number of peaks to be found in the IR spectrum (6 as opposed to 3). Closer examination of the data makes the explanation for this clear. Firstly, the vibration at 2593cm-1 has an intensity of 0, so does not appear. This is a result of the vibration being totally symmetrically, and hence, IR inactive. Secondly, we have two sets of degenerate vibrations, which are therefore indistinguishable - these are marked with the symmetry label E (for one set) and E' (for the other).

NBO Analysis

This is the .log file for the calculations described below.

NBO (Natural Bond Orbital) analysis is a useful tool in determining the nature of the bonding in a molecule. Essentially, the method consists of dividing the electron density of the molecule up between the atoms based on a population analysis (this sort of calculation is also the basis of the MO analysis discussed below). Each atom can be assigned an overall charge. Additionally, NBO analysis provides information about the hybridisation of bonds in a molecule, describing, in this instance, how much s/p character a bond displays.

The representation of the distribution of electron density can be seen below.

Charge numbers are included (one can see that the total charge is equal to zero, as you would expect). The fact that the boron atom has more electron density around it is hardly surprising when considering the respecting electronegativities of boron and hydrogen. This is the sort of picture we would expect.

Here you can see the part of the file which describes the hybridisation of the various occupied molecular orbitals.

(Occupancy) Bond orbital/ Coefficients/ Hybrids

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 2

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.8165 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 2 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

2. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 3

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 -0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 3 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

3. (1.99851) BD ( 1) B 1 - H 4

( 44.49%) 0.6670* B 1 s( 33.33%)p 2.00( 66.67%)

0.0000 0.5774 0.0000 0.7071 0.0000

-0.4082 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

( 55.51%) 0.7451* H 4 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000

4. (1.99904) CR ( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

1.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000

5. (0.00000) LP*( 1) B 1 s(100.00%)

Here we have 1 orbital entirely s in character (the non-bonding orbital produced by the boron atom's 1s atomic orbital) and 3 sp2 orbitals, which are the bonds between the boron centre and the three hydrogen atoms. This agrees with what we would expect, and fits with the trigonal planar geometry of the borane. The lone pair is also shown, for some reason, the calculation gives the result that this orbital is totally s in character, when we would expect it to be totally p. The explanation might be to do with the fairly simple basis set being used, and a more advanced method might yield a different result.

MO Analysis

Computational methods provide a way of better understanding molecular orbitals. MOs often have complicated three-dimensional shapes, and while we can gain an appreciation of what they might look like using LCAO, this often provides quite a rough approximation. Computational chemistry enables the visualisation of MOs in three-dimensions.

The .log file resulting from the calculations that were carried out can be found here, the checkpoint here. This .log file is the same as the one resulting from the NBO analysis above.

A molecular orbital diagram for this molecule produced using LCAO can be seen below, this will be compared with the results calculated, as a simple way of judging the success of the exercise.

| Orbital | Symmetry | Energy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO-3 |  |

1a'1 | -6.730 |

| HOMO-2 |  |

2a'1 | -0.517 |

| HOMO-1 |  |

1e' | -0.356 |

| HOMO |  |

1e' | -0.356 |

| LUMO |  |

1a2 | -0.074 |

| LUMO+1 |  |

3a'1 | 0.188 |

| LUMO+2 |  |

2e' | 0.188 |

| LUMO+3 |  |

2e' | 0.191 |

As can be seen when comparing the two pictures of the orbitals, there is a great deal of similarity between the orbitals suggested by the LCAO diagram and those generated computationally. This is perhaps most marked for the lowest energy orbitals (which is hardly surprising, since they are derived from s orbitals). In cases of significant overlap between bonding orbitals, the calculations prove particularly valuble, since simple LCAO by hand is poor at representing these interactions. It is also worth noting that the relative energies that the orbitals take up is generally as expected, since the degree of mixing here is relatively easy to determine. This will inevitably become much harder as molecules become more complex. This will mean that calculations will take longer, and perhaps become less reliable. Crucially however, LCAO by hand will become extremely labourious for very complicated molecules, making the computational approach rather attractive.

Analysis of TlBr3

Optimisation

Thallium bromide optimisation output.

The optimisation of thallium bromide is a slightly more complex affair, while the molecule appears to be very simple, it has many more electrons making calculations more difficult. To shorten the time required for calculations two steps were taken. Firstly the point group was pre-defined as D3h, which essentially requires a set arrangement of the bromine atom around the central atom relative to one another. This means that there are many fewer possible arrangements for the program to calculate. The second step taken to accelerate the calculation was to employ a pseudo-potential (PP). This sort of approximation only runs calculations for the electrons that are involved in bonding - valence electrons. The other electrons are simply assigned to belong to a core potential and cannot be involved in bonding. The fact that this approach yields rather accurate results suggests that the assumption made that only the electrons which are highest in energy make a significant contribution to bonding is a valid one. The basis set (making use of a PP) here was LANL2DZ with a RB3LYP method.

This is the information from the calculation summary provided by Gaussview: showing the bond distance, angle and some information about how the calculation was run.

'''''TlBr3 Data''''' ''Bond Distance: 2.65095'' ''Bond Angle: 120.000'' ''File Type: .log'' ''Calc Type: FOPT'' ''Calc Method: RB3LYP'' ''Basis Set: LANL2DZ'' ''E(RB+HF-LYP): -91.21812851 a.u.'' ''RMS Gradient Norm: 0.00000090'' ''Imaginary Freq: '' ''Dipole Moment: 0.0000 Debye'' ''Point Group: D3H'' ''Job Time: 4 minutes 22.0 seconds''

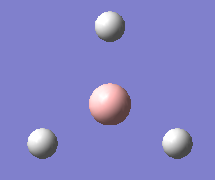

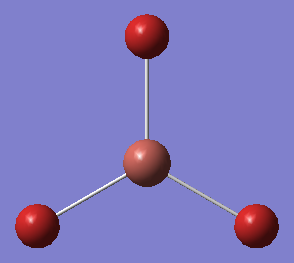

The final appearance of the molecule was as follows:

The Tl-Br bond length was found to be 2.65Å, close to the literature value of 2.51Å [1]. The bond angles were as expected (and were always going to be, since the point group was pre-defined).

Frequency Analysis

Frequency analysis output file.

The frequency analysis was run here to check whether the previous calculations had run properly, as described in the BH3 section above. The important part of the file to investigate was the low frequencies part:

Full mass-weighted force constant matrix: Low frequencies --- -3.4226 -0.0026 -0.0004 0.0015 3.9361 3.9361 Low frequencies --- 46.4288 46.4291 52.1449

This shows that a number of the frequencies are slightly negative. However in the case of two of these they are extremely close to zero so are not of concern. The value of -3.4226 is also acceptable, being within 10cm-1 of zero. These slight negative numbers result from numerical errors in the calculation (due to the low level method being employed), rather than any underlying physical property.

A bond can, in simplistic terms, be described as a stable, attractive interaction which exists between two molecules. Essentially, electron density existing between two nuclei acting as a sort of electrostatic glue gives a bond. One way to think about a bond is in terms of two atomic orbitals overlapping to give a molecular orbital. This leads to the conclusion that these interactions are not purely localised between specific atoms, but spread over the whole molecule. However, it aids our understanding to draw bonds as lines between specific atoms, so this is useful. Gaussview draws bonds based on distance, if atoms are further than a set distance apart, it will not draw a bond, even if has calculated that there may be a significant attractive interaction between a pair of atoms.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

This section deals with the study of the cis- and trans- isomers of Mo(CO)4L2. In practice, L is PPh3, but to make calculation more straightforward, the Ph groups are replaced by Cl atoms, which give a reasonably good electronic approximation for benzene, whilst being much more simple to compute.

Optimisations

The structures were drawn in Gaussview and an initial optimisation performed using the DFT-B3LYP method and the LANL2MB as the basis set (opt=loose was added to the additional keywords section). The calculations gave the following results: for cis and trans.

As you can see, the optimisation has lead to the disappearance of the P-Cl bonds, this is not because the chlorine atoms are suddenly cut loose. What has happened is that the ideal internuclear distance has been determined as greater than the upper threshold for a drawing a bond (as defined by Gaussview).

The optimised forms of the molecule could exist in a false minimum, i.e. a lower energy conformation may exist. To check this, the arrangement of both isomers was altered slightly. The cis- isomer saw its groups rotated to torsion angles of 0° and 180°. The trans- isomer saw its PCl3 groups arranged into an eclipsed conformation, with one P-Cl bond aligned with one of the C=O units.

These new structures were optimised again, this time using the more accurate basis set: LANL2DZ. This gave results as follows: cis and trans.

According to Gaussview, these new arrangements are a little more stable, with slightly lower energies. This shows that the previously optimised structures were examples of false minima. To provide an even better approximation of these isomers, we should take account of phosphorous' low-lying d-orbitals, which can be used in bonding.

To include these orbitals, it is necessary to edit the input file directly. The additional keyword "extrabasis" needs to be included for obvious reasons. The extra orbitals are added at the end of the file, as follows:

(blank line) P 0 D 1 1.0 0.55 0.100D+01 **** (blank line)

Both isomers were given this treatment and these files was submitted for a final optimisation. Giving the following results cis and trans.

The energies of the two isomers are more or less the same, with no significant difference: cis- -623.693 a.u. and trans- 623.694a.u..

As far as which isomer is the more stable we have two competing factors at work which, in this case, roughly balance one another. On one hand we have the steric repulsions between the two PCl3 groups in the cis- isomer., on the other the fact that -CO is a good pi acceptor. This means we would expect to observe a strong trans-effect, with the P lone pair donating electron density into the π*CO orbital, a form of enhanced back-bonding when the ligands are trans to one another. This makes it favourable for the a CO group to be trans- to a PL3 ligand, i.e. this promotes the cis- isomer.

We should at this point bear in mind the fact that the molecule we are using here is not exactly identical to the one we are really interested in. If we were to reintroduce the Ph groups in place of the Cl atoms that have been substituted for them, we would see a sizeable increase effect from sterics. This would lead to distortion of the octahedral geometry, as reported in the literature[2]. This would naturally make the isomer much less stable meaning trans- would become more favoured.

The table below provides some bond lengths from the two isomers.

| / Å | trans- isomer | cis- Isomer | ||||

| Bond | Length | Lit[2]Length | trans- to P Length | Lit[3] | cis- to P Length | Lit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-Mo | 2.06 | 2.01 | 2.02 | 1.97 | 2.06 | 2.06 |

| C=O | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.17 | 1.16 |

| Mo-P | 2.42 | 2.50 | 2.47 | N/A | N/A | 2.58 |

Vibrational Analysis

Frequency analysis was again performed to check the validity of the calculations, and to compare with literature IR data. The results of those calculations can be seen for cis- and [ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7815 trans-].

The low frequencies section of the two files show that the calculations have been successful, and that the geometries found are appropriate. These low frequency vibrations are animated here:

The lowest vibrations in each set see the PCl3 group rotate about the P-Mo bond, this is a very low energy motion, so would take place at room temperature.

Of considerable interest (particularly with regards to characterisation) are the stretching frequencies of the C=O groups, these are tabulated below:

| Symmetry | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency - Mo(CO)4PCl3[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | 1938 | 1605 | 1986 |

| B1 | 1941 | 813 | 1994 |

| A1 | 1952 | 588 | 2004 |

| A1 | 2019 | 544 | 2072 |

| Symmetry | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency - Mo(CO)4PCl3[4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu | 1939 | 1605 | 1896 |

| Eu | 1939 | 1605 | 1896 |

| B1g | 1967 | 6 | |

| A1g | 2025 | 5 |

As you can see from the spectrum, four significant separate stretches exist for the cis- isomer (although two may be close enough to merge in the calculated version), and only 1 significant stretch exists (one degenerate pair, and two which do not appear to be IR active) for the trans- form. This is due to the high degree of symmetry which the trans- form has, essentially, all of the CO ligands are equivalent, they all exist in the same environment. The cis- form has less symmetry, so we see multiple peaks.

The values for frequency are a little lower than those from the literature. One reason for this might be that PCl3 is a less good pi donor than PPh3. This will mean that the degree of backbonding in CO will be different in the two molecules, and hence the bond strength will be altered. This would explain the difference in frequency.

Mini Project: Aromatic Cyclopropenium, Cyclotrisilenium and Cyclotrigermenium Cations

It has long been known that it is possible to generate cyclopropenium ions that exhibit Hückel aromaticity (4n+2 pi electron where n=0).

What has only become clear more recently (in the past decade or so) is that this principle can be extended to larger elements in Group 14 (e.g. Silicon and Germanium)[5][6].

If a molecule is aromatic it should possess a wide range of properties. Amongst others these should include: resonance stabilisation, equalised bond lengths and magnetic effects. Some of these are relatively easy to probe using computational chemistry, for example bond lengths, others such as resonance stabilisation are much harder to compute with a high degree of certainty. It might also be of particular interest to investigate the form of the molecular orbitals of the molecules, to see if one can identify the sort of extended pi systems often associated with aromaticity. It could prove worthwhile to investigate the vibrations of the molecules, and to look at the 13C NMR of the carbon based compound to identify the sort of ring current that aromaticity causes.

To make the Si and Ge compounds large bulky protecting groups (generally -SitBu3) are used. These are too large to be computed easily, so need to be approximated to something smaller. Simply replacing the tBu groups with methyl groups would be an improvement, giving a good approximation, but this might still be a little too large. For the sake of fast calculations, -SiH3 will be used to act as a replacement for the larger group. This should still provide a useful model.

Optimisation

The first task is to produce optimised geometries for the three compounds. This in itself will be useful exercise in analysing the aromatic nature of the compound, because we should expect to see 3 equivalent atoms in each of the rings with equal bond lengths, rather than one short double bond and two longer single bonds.

Optimisation outputs: C , Si , Ge .

The lengths of the bonds in the rings were all uniform for each molecule, for C: 1.40A, for Si 2.28A and for Ge 2.41A. This is a good indicator of aromaticity. We see the sort of increase in size that we would expect with increasing atomic radius.

In the case of the Ge compound, a PP was used for this step due to the high number of electrons present:

Ge 0 LanL2DZ **** Si H 0 6-311G(d,p) **** Ge 0 LanL2DZ

Vibrations

Data: C, [http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7883

Si], [ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7884 Ge]

Here, by way of example is the low frequencies section of the output file relating to Ge:

Low frequencies --- -0.0001 0.0000 0.0000 3.4893 3.6887 4.2243 Low frequencies --- 36.8545 41.2134 52.7060

Frequency analysis was run in order to generate a IR spectrum and to analyse any particularly interesting vibrations that might appear.

Here are the spectra:

|

|

|

As can be seen by the relatively sparse spectra, there are not very many significant vibrational modes. More interesting is the fact that what modes do exist are generally confined to the protecting groups. The rings seem to rigid, to constrained to see very much vibration at all. On one level this makes sense, because there are so few members in the ring even small movements for one of the three atoms would produce a large distortion in the bond opposite.

NBO Analysis

The population analysis files for NBO/MO data are here: C, Si, Ge.

One interesting point that can be seen clearly using NBO charge distribution analysis is that as we move up the period the direction of the electro density gradient reverses. For the carbon based ring, the ring has the most density, in the other two cases, the protecting silicon atoms do.

|

|

|

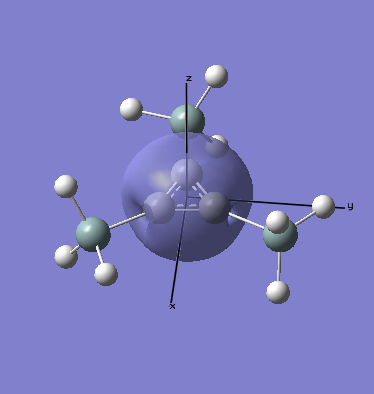

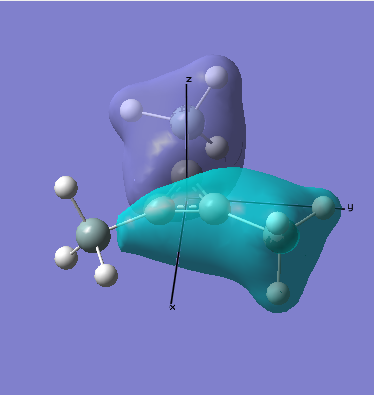

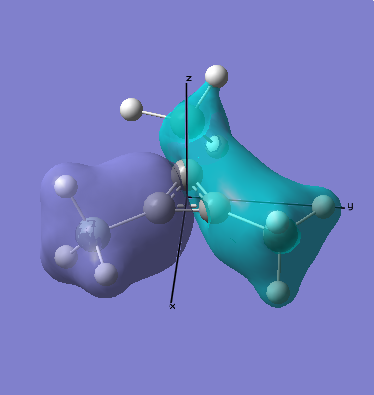

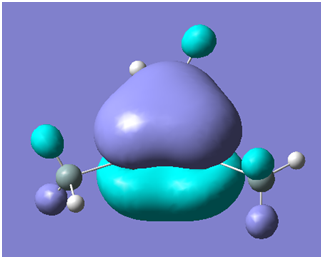

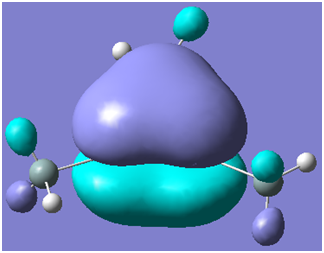

MO Analysis

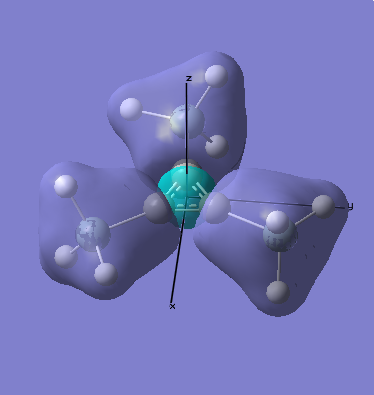

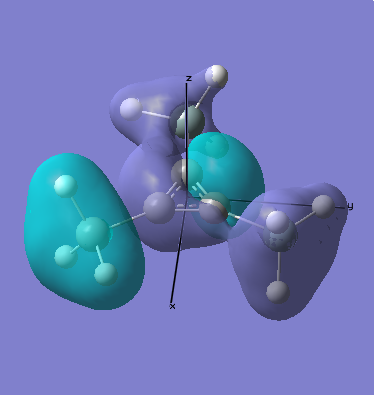

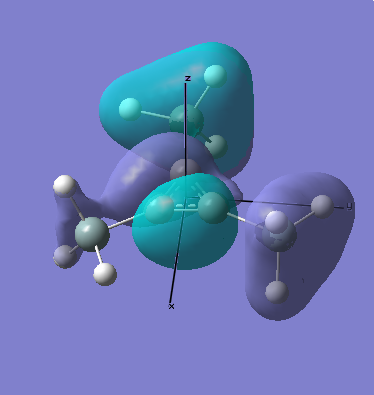

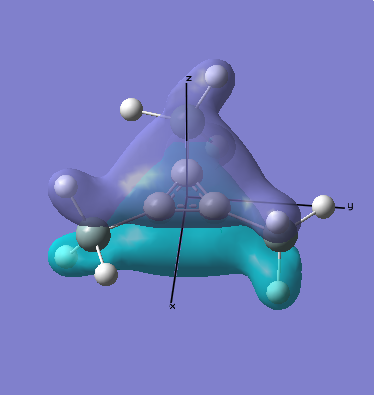

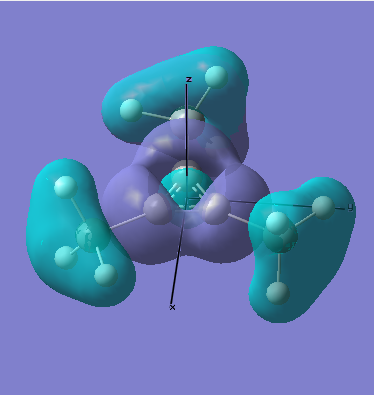

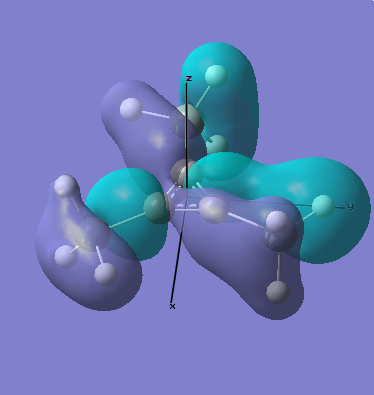

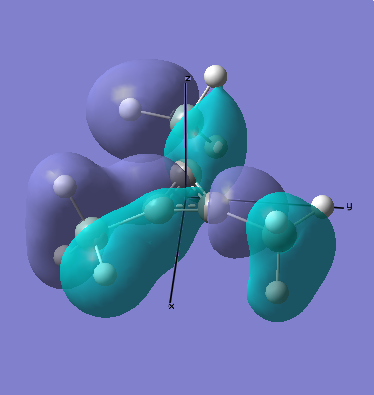

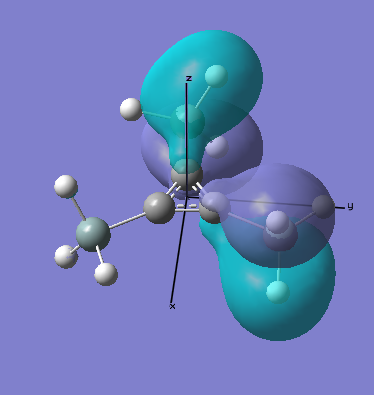

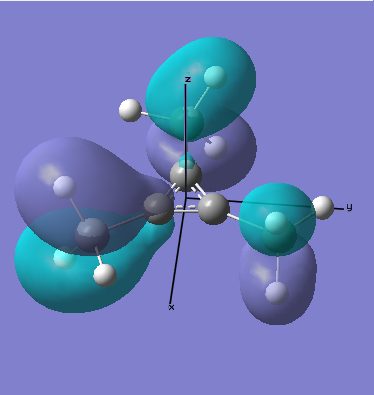

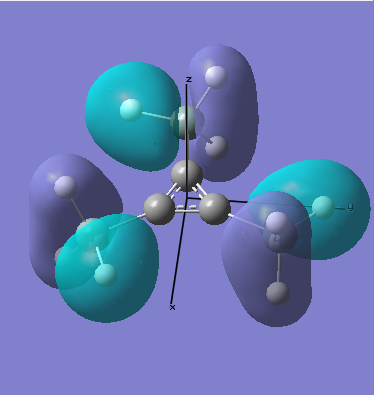

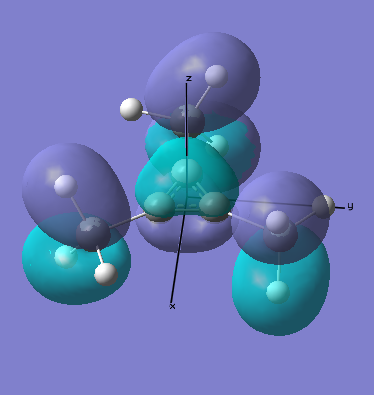

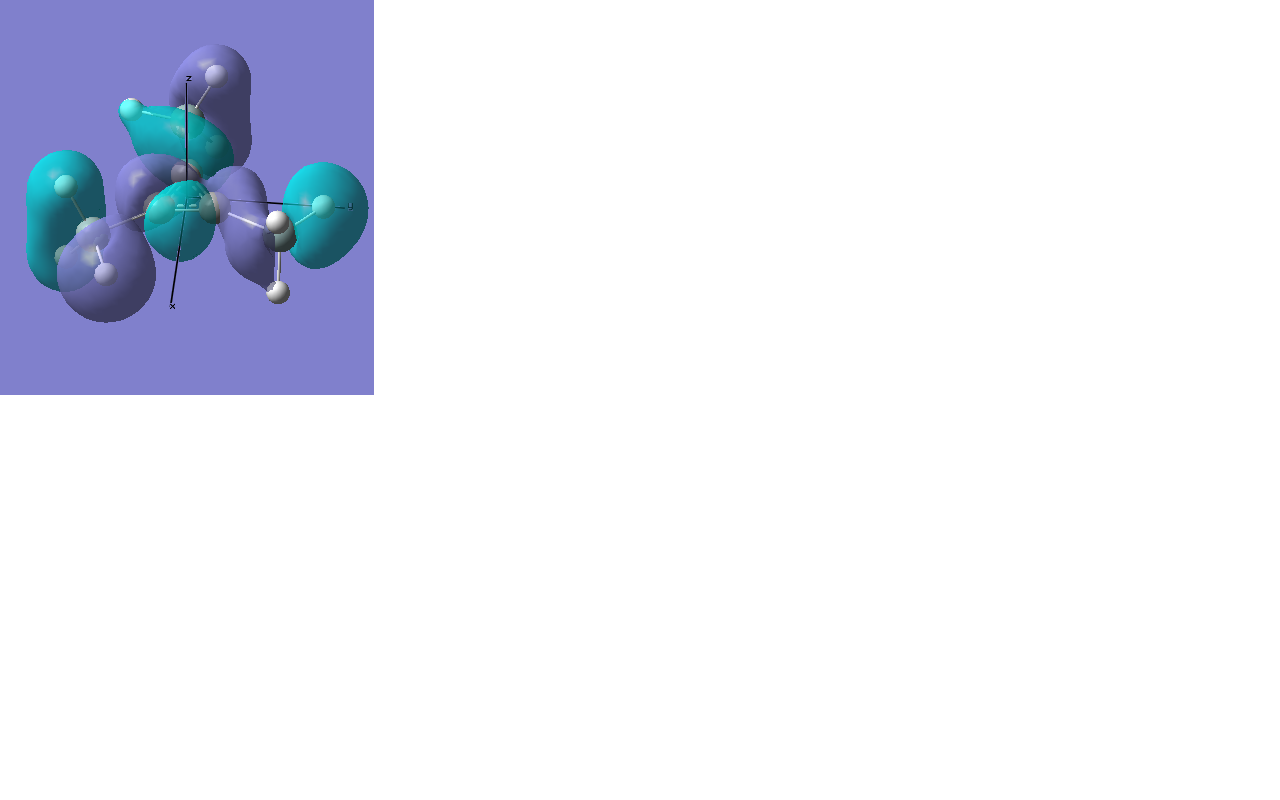

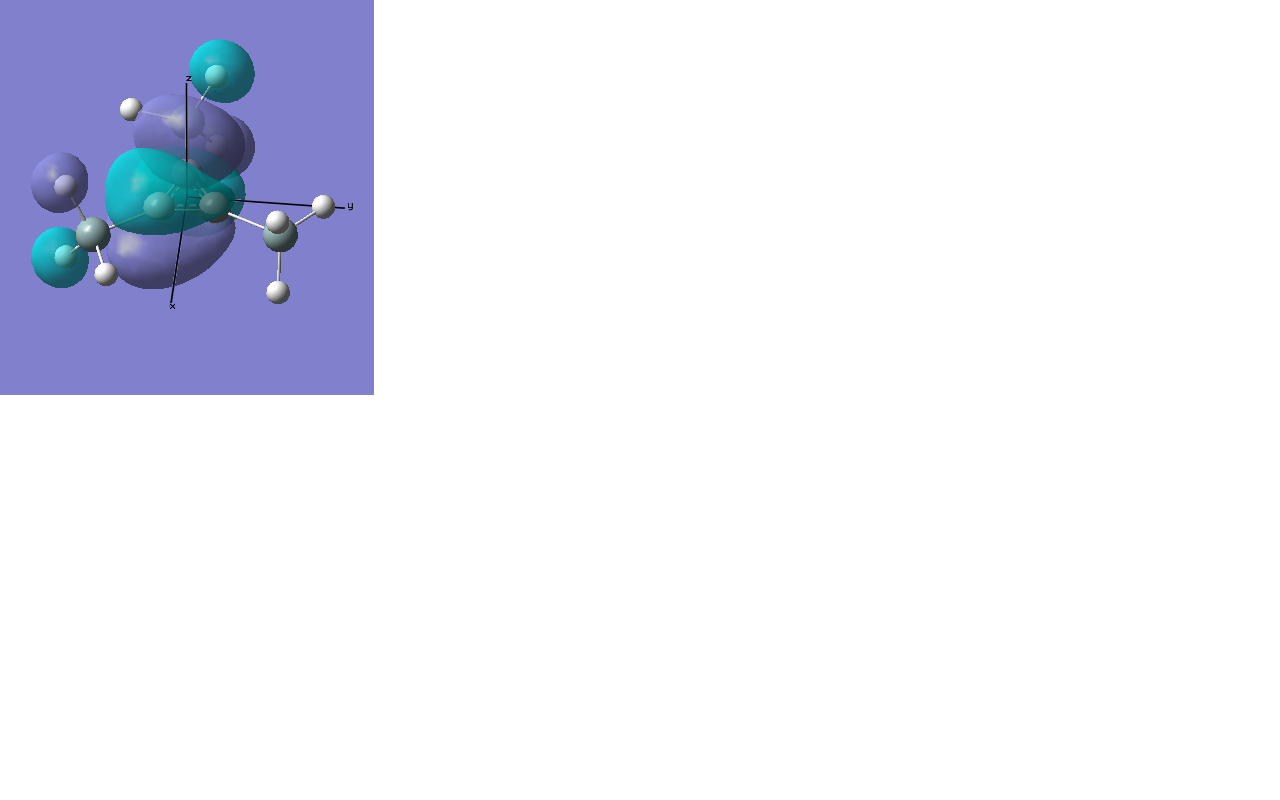

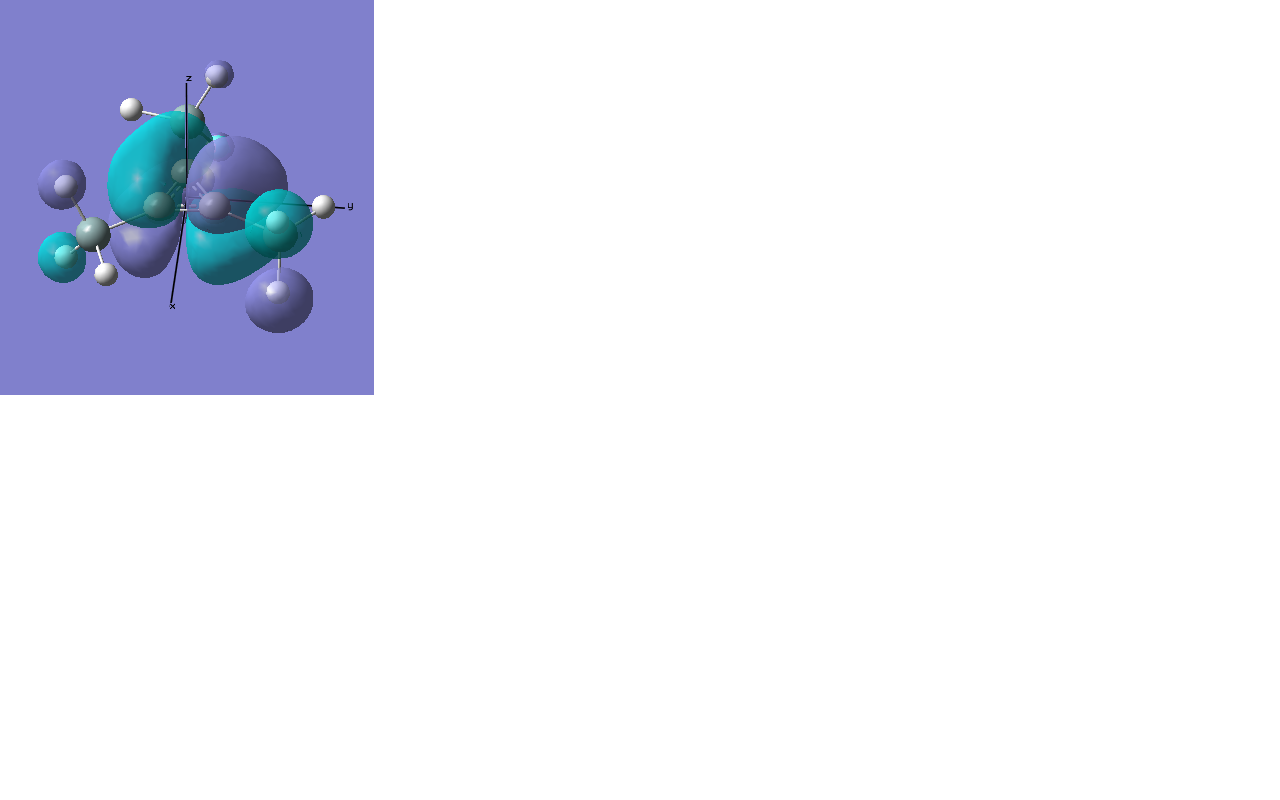

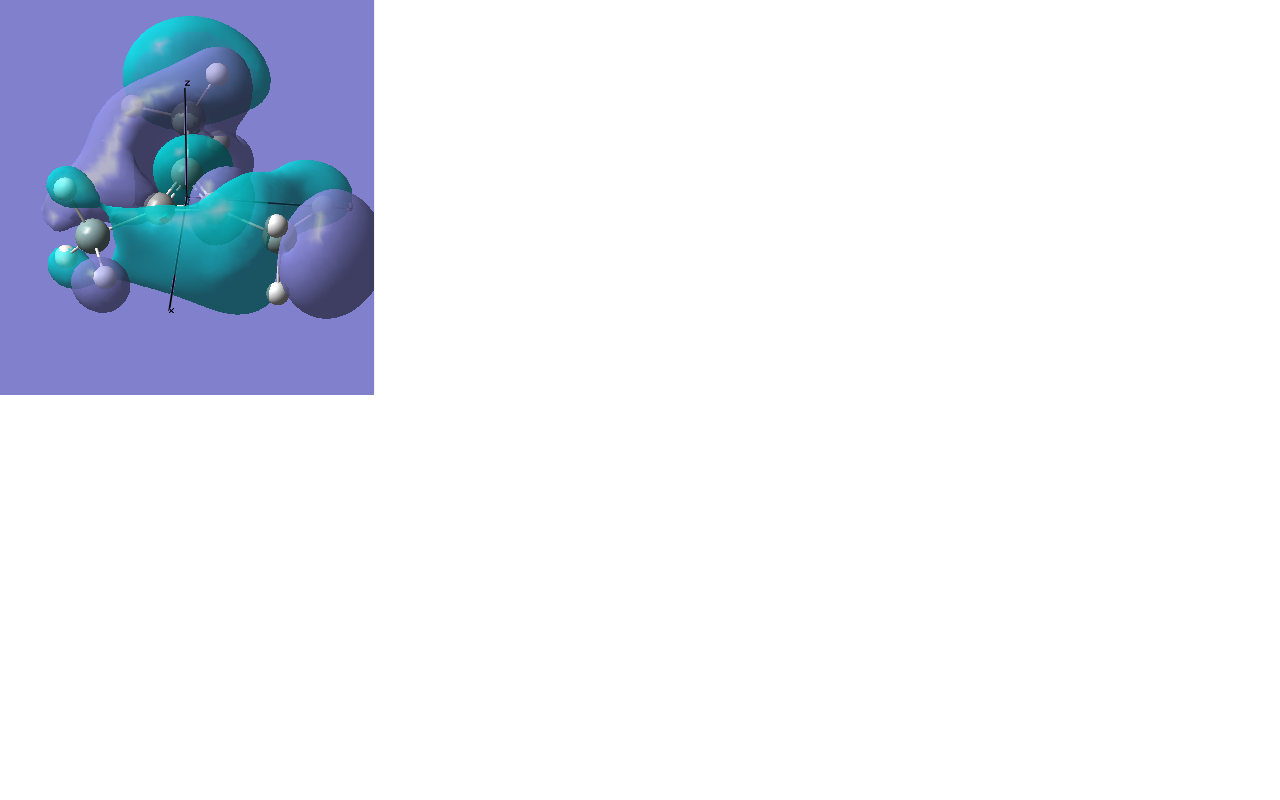

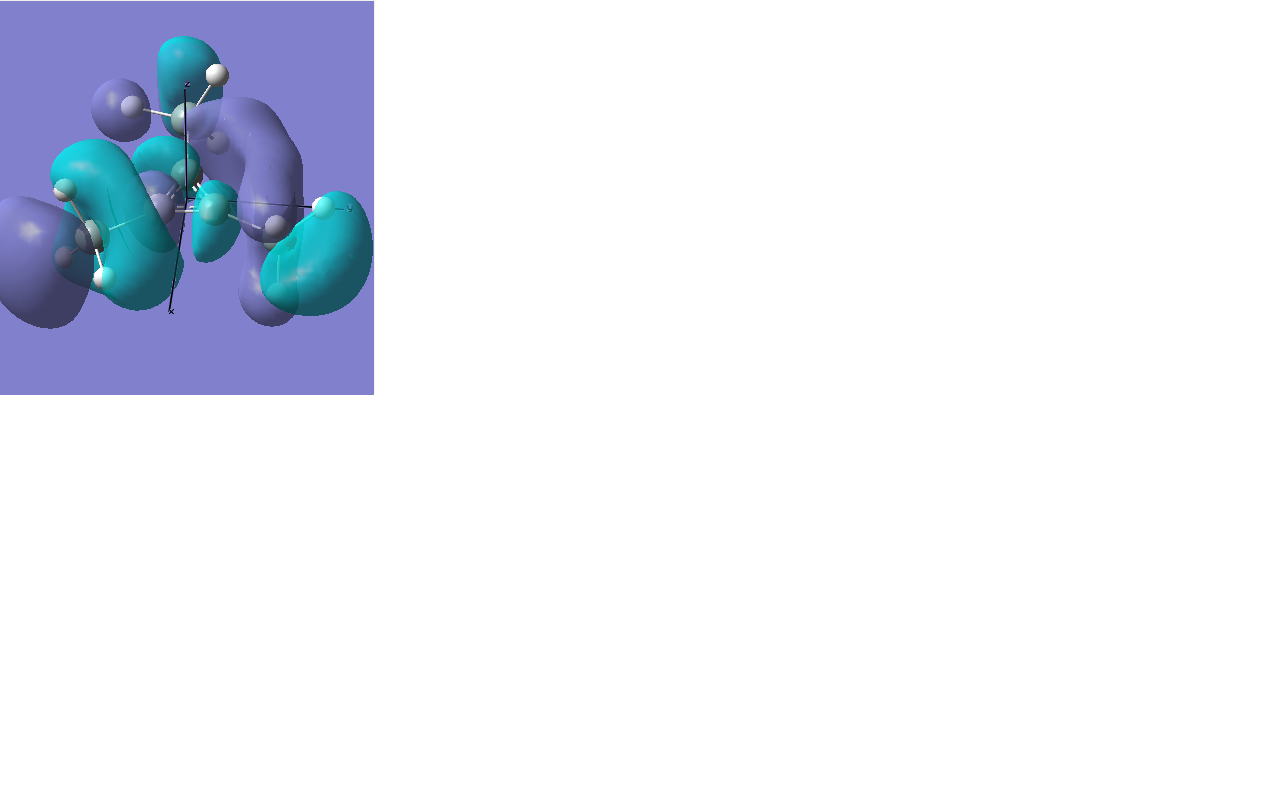

All occupied bonding MOs, and the first few unoccupied orbitals are shown below. The list starts at orbial 19, up to orbital 18, no overlap takes place, and we essentially see AOs.

There are two occupied MOs which show clear aromatic character, 25 and 32. These have well-developed pi systems delocalised over the whole molecule and the whole ring respectively.

As can be seen by looking at these two orbitals (the HOMOs for the silicon and germanium based compounds respectively), aromaticity exists in all three compounds' MOs. The system becomes more diffuse for the larger elements as you would expect. Generally speaking similar shapes of orbitals are visible for all three molecules over the whole energy range, this underlines the similarity between the different molecules.

13C NMR Analysis

13C NMR shift was recorded at with 1 peak at 176.0ppm. This is evidence of a ring current, and along with the equivalence we can see, is further evidence of aromaticity.

Conclusions

The uses of computational techniques in generating data for a compound and providing powerful ways to visualise that data are clear in this mini project. It would have been impossible to visualise some of the extremely complex MOs generated by Gaussview. These were of considerable value in illustrating the aromaticity of the compound being studied. Various other techniques, in particular geometry optimisation, but also vibrational and NBO analysis have been shown, throughout this project to be extremely valuble in providing a new tool in understanding chemical systems.

References

- ↑ J. Glaser and G. Johansson, Acta Chemica Scandinava, 1982, 36, 125-135. DOI:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.36a-0125

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254 (1), 167 DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(96)05133-X

- ↑ F. A. Cotton, D. J. Darensbourg, S. Klein, B. W. S. Kolthammer, Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21 (1), 299 DOI:10.1021/ic00131a055

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Elmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 3864-3873

- ↑ Sekiguchi et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11250. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ja002344v

- ↑ Sekiguchi et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 1158. http://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/ja012216m