Rep:Mod2:cb208

Module 2: Inorganic Computational Chemistry

Introduction and Aims

Inorganic computational chemistry can be used to help give an insight into the bonding and structure of complexes. This is particularly important due to the complex nature of inorganic compounds. Computational chemistry can also be used to differentiate between different conformers energies, and identify both transition states and activated complexes, which could not otherwise be found. The properties of inorganic compounds can now also be predicted accurately, including NMR, IR, Raman spectra, and their electron density.

In this project a number of experiments will be carried out to explore the uses of computational chemistry in investigating both bonding and reactions in inorganic molecules. The results of the calculations run on Gaussian are given to a higher accuracy than the methods can asertain, and so have brackets around the values that are beyond the methods accuracy.

Small Molecules - Structures and Bonding

Borane (BH3)

Geometry Optimization

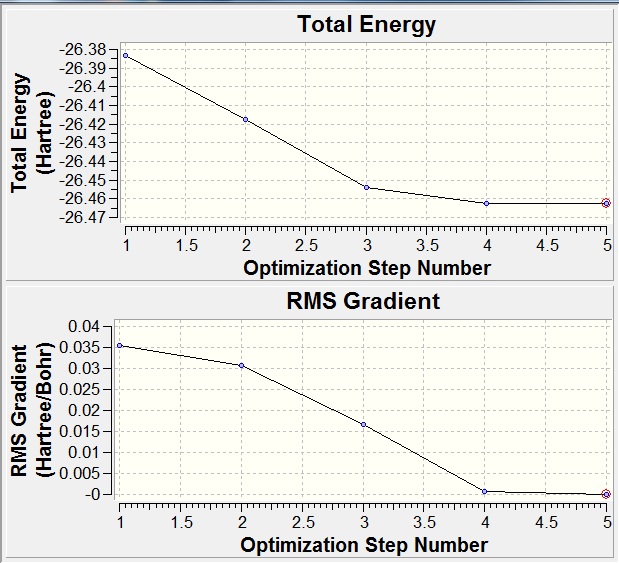

The BH3 molecule was drawn using GaussView 3, and optimized using the B3LYP (Becke-3-Parameter, Lee Yang Par) method with the 3-21G basis set. This optimization consists of two parts, firstly the SCF which assumes that the nuclei positions are fixed and the Schrodinger equation is solved for electrong density; and secondly the OPT which changes the position of the nuclei and repeats the SCF to find the lowest energy structure.

| Bond Length / Å | 1.19(435) |

| Bond Angle / ° | 120 |

| Energy / a.u. | -26.46226438 |

The bond length is in agreement with that expected from literature[1], and the bond angle is the same as that expected from VSEPR.

The summary file for this calculation gave the following information.

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Energy | -26.46226438 a.u. |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.00000285 a.u. |

| Dipole Moment | 0 debye |

| Point Group | D3H |

| Calculation Time | 1min 37sec |

Log File: DOI:/10042/to-7466

The RMS gradient of 0.00000285 a.u. is less than 0.001 a.u., which shows that the optimization was performed successfully. This is also confirmed by the output file which states that all parameters converged. The graphical representation of this is shown below.

Calculation of the Molecular and Natural Bond Orbitals

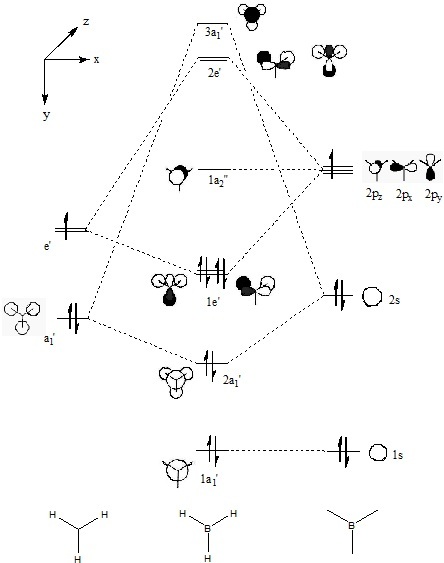

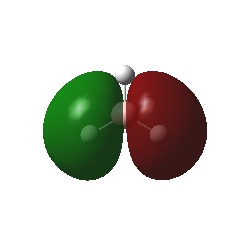

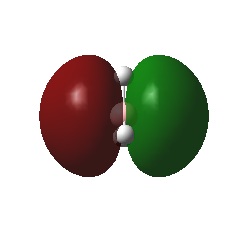

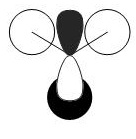

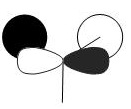

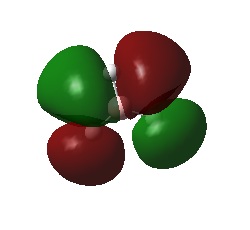

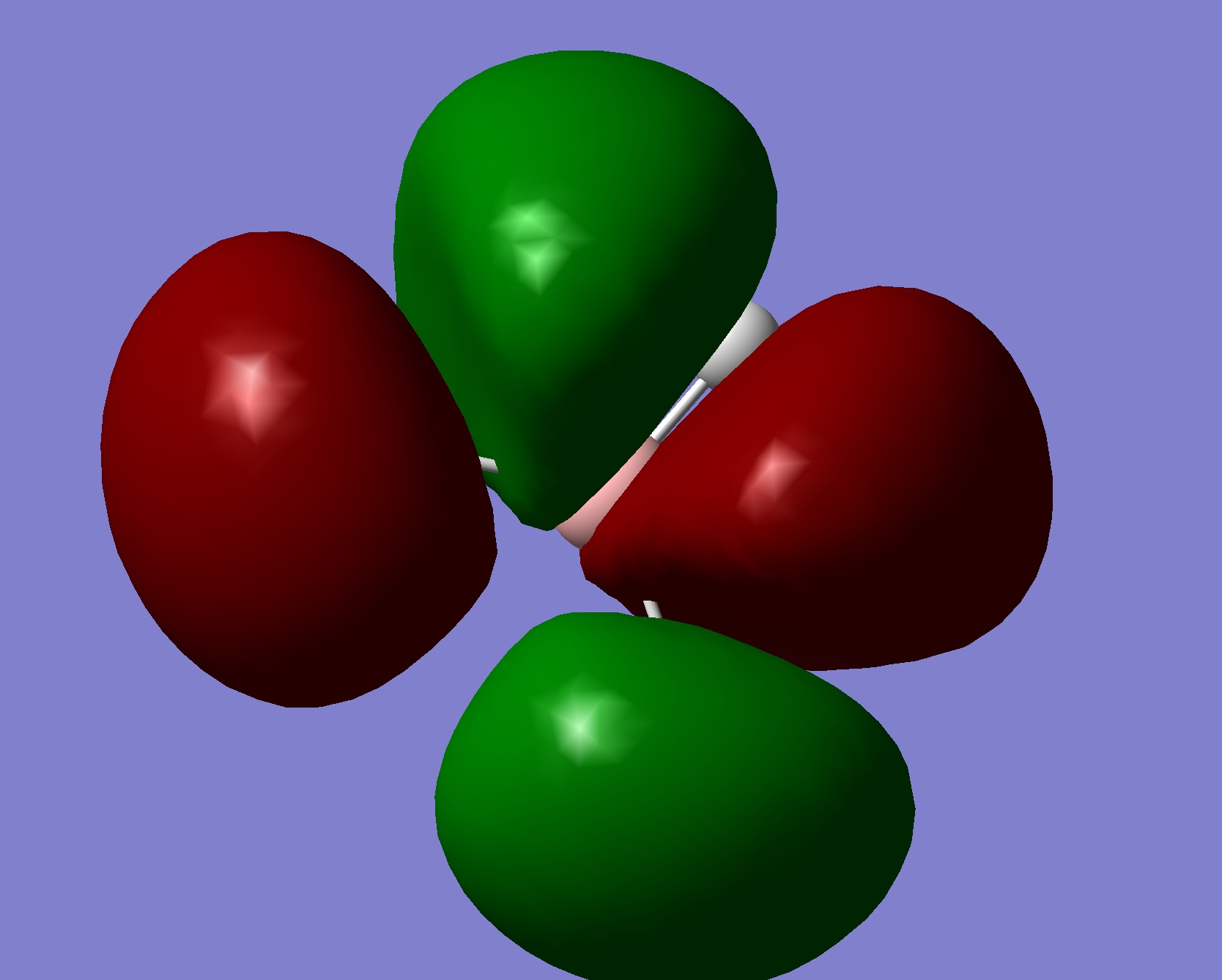

A very useful tool in computational chemistry is the ability to calaculate the molecular orbitals of a compound. In order to determine how well these molecular orbitals are calculated they will be compared to the molecular orbitals formed by the LCAO method shown below.

A further calculation was run on the optimized BH3 molecule, in order to determine its molecular and natural bond orbitals (using the input: b3lyp/3-21g pop=(nbo,full) geom=connectivity). Each calculated MO corresponds directly to that of one determined using the LCAO method, and so the two can be compared. Output File: DOI:/10042/to-7467

The above comparison shows that both the LCAO and calculated molecular orbitals are in very good agreement of the general shape of the MO's. However, the calculated MO's are able to give better 3D representations of the finer details, especially in the more complex cases.

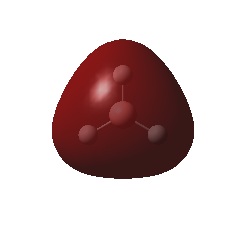

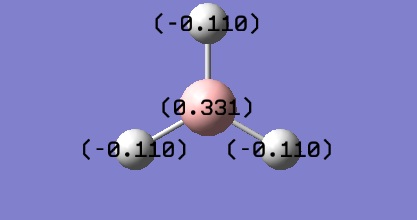

The natural bond order calculations are able to give a better representation of the charge distrubtion over the molecule. This is best shown visually.

It can be seen that each of the hydrogen atoms carrys the same (due to symmetry of the molecule) negative charge (-0.110) and the boron centre a positive charge (0.331), the is expected as the boron is the more electropostivie atom. From the log file it can be seen that the atom has a total charge of 0, which is to be expected of a neutral molecule.

The log file also shows that for the bonding orbitals of boron the s-orbitals contribute 33.3% and the p-orbitals 66%, showing sp2 hybridisation at the boron centre. Each boron-hydrogen bond is made up from 55.51% electron density from the hydrogen and 44.49% from the boron.

Vibrational Analysis of BH3

The vibrations of BH3 were calaculated (DOI:/10042/to-7476 ). This is to confirm that the optimized strucutre is a minimum on the potential energy surface, rather than a maximum (a transition state), if all the vibrations are positive then the optimized structure is correct (if a negative value is found then the strcuture is a transition state). In this case all the frequencies are positive and so the optimized structure has been correctly calculated.

As expected from the 3N-6 rule 6 different vibrations were found (each with a symmetry related to the D3H point group). It was found that the energy after the calculations was equal to that of the optimization (-26.46226438 a.u.), showing that the calculated results are still valid.

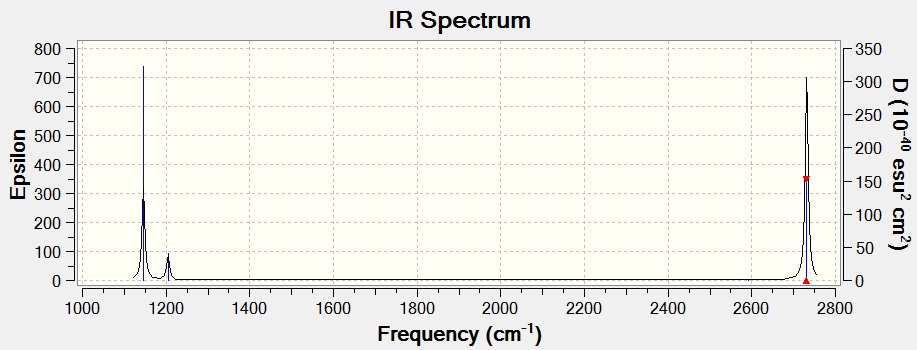

The IR spectrum above shows just three peaks (1145, 1204, 2731 cm-1. This is because there are two doubly degenerate vibrations (1204 and 2731 cm-1), and so appear at the same position giving just one peak between them. The peak at 2592 cm-1 is also not present on the IR due to it not being IR active (shown by its intensity of 0), this is because it is a completely symmetric vibration and so has no change in dipole moment.

Thallium Bromide (TlBr3)

Optimization

TlBr3 was drawn in GaussView 3 and optimized using the B3LYP method and the LanL2DZ basis set (a medium level basis set opposed to the more simple 3-21G set used before). This molecule requires the more complex basis set because of the heavier elements present, which has more complex electronic structures. The LanL2DZ basis set assumes that core electrons act as an effective potential (rather than a calculation for each electron), and so assumes only valence electrons are used. The symmetry of TlBr3 was constrained to the D3h point group, with a high tolerance (0.0001). Output File: DOI:/10042/to-7485

| Bond Length | 2.65(095) Å |

| Bond Angle | 120ᵒ |

| Energy / a.u. | -91.21812851 |

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.0000009 |

| Dipole Moment | 0 |

| Point Group | D3H |

| Calculation Time | 20.5 seconds |

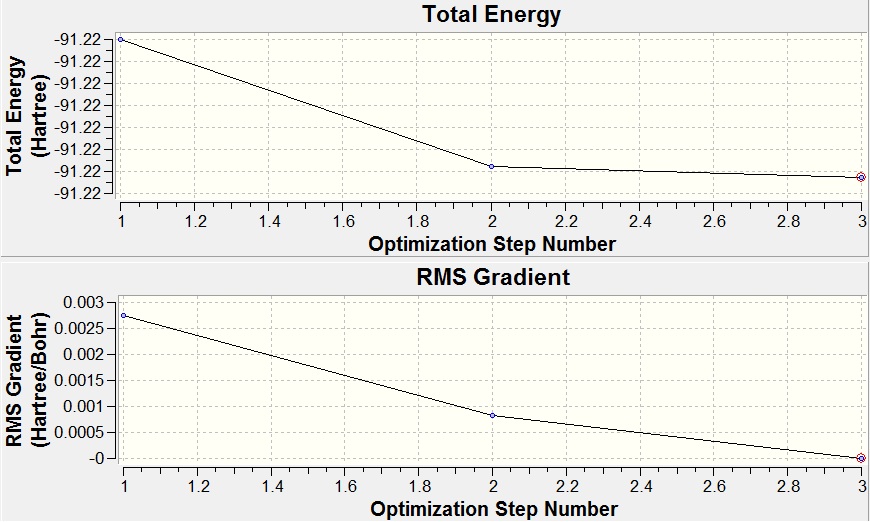

The optimized bond length was found to be 2.65Å and the bond angle 120ᵒ, these values compare well to that of literature[2] which has values of 2.52Å and 120ᵒ. The slight difference between the two bond lengths is due to the approximations used in the caculations. The RMS Gradient Norm of 0.0000009 a.u. shows that the optimization has reached a minimum, further shown by the graphs below.

Vibrational Analysis

Analysis of the frequency of TlBr3 is required to find whether or not the structure had been fully optimized to a minimum; if so all the vibrational frequencies should be positive. This is because the frequency analysis is the second derivative of the potential energy surface and so should be positive to show a minimum, negative values would show a transition state had been calculated. The calculation was carried out using the B3LYP methods and the LanL2MB basis set, this is the same as used in the optimization calculation to ensure that the results are calculated in the same way and so are compareable. Two different calculations could not be carried out for each part as both would model slightly different potential energy surfaces which would not be compareable.

| Low Frequencies / cm-1 | Lowest "Real" Normal Frequencies / cm-1 |

|---|---|

| -3(.4213) | 46(.4289) |

| -0(.0026) | 46(.4292) |

| -0(.0004) | 52(.1449) |

| 0(.0015) | - |

| 3(.9367) | - |

| 3(.9367) | - |

Output File: DOI:/10042/to-7525

All of the "real" frequencies are positive, this confirms that the optimized structure calculated is at a minimum on the potential energy curve. The "low frequencies" are all very close to zero, and some are negative due to numerical difficulties, this shows that the method and basis set are fine for this analysis.

Again as expected (from the 3N-6 rule) six different vibrational modes are present.

| Frequency cm-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|

| 46(.4289) | 3(.6867) |

| 46(.4292) | 3(.6867) |

| 52(.1449) | 5(.8455) |

| 165(.268) | 0(.000) |

| 210(.695) | 25(.4830) |

| 210(.695) | 25(.4797) |

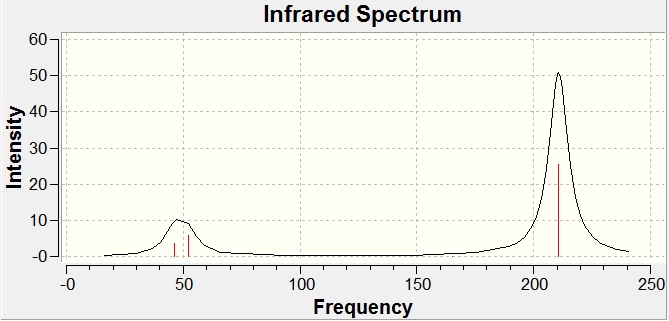

It can be seen from the spectra above that again (as in the BH3 case) only 3 peaks are present, this is again due to two sets of degenerate vibrations and one IR inactive vibration.

Chemical Bond Discussion

GaussView will not always display certain bonds, this is because only bonds are only drawn when they fit set parameters used by the program to describe a bond. If a calculated bond is not within these parameters then it is not considered a bond, this however does not mean there is not one there, as can be seen from the vibrational frequencies. One of these parameters is bond length, and if the bond is longer than this then it is not considered a bond by the program, this was shown in the BH3 example when the "bonds" disappeared when the bond lengths were set to 1.5Å.

A bond is an electronic interaction (ionic, covalent, dipole-dipole ect.) between atoms that leads to a lower energy than that of them seperated. There is no set point where a bond stops being a bond because it is dependant on the atoms involved.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Introduction

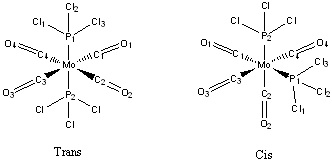

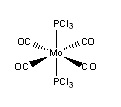

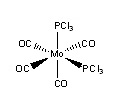

The Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 complex can display cis and trans isomerism. In this section the complex will have its geometries optimized and a vibrational frequency analysis conducted to investigate the different properties between the two, especially looking at the CO vibrational frequencies.

This complex was chosen due to its close resemblance to Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, for which crystal data is available[3]. The phenyl groups have been replaced with chlorine groups (so there are far less atoms in the structure), which makes the calculations far more time efficient. The PCl3 ligand is much smaller than the PPh3 ligand, but is still reasonable for this experiment.

It is expected that the biggest factor in this cis/trans isomerism is likely to be sterics, and so larger ligands are going to prefer the trans isomer. The different symmetries of the isomers (C2v and D4h) will cause them to have a different number of vibrational frequencies, with the cis isomer expected to have more than the trans isomer. CO ligands have very distinct vibrational frequencies(1700-2000cm-1), and so are ideal to study in this experiment.

Optimization

The structures of both the trans and cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 were optimized in three stages using the B3LYP method in Gaussian. First (optimization 1), the LANL2MB basis set was used, along with the additional “opt=loose” input, this initial calculation is used to quickly find a structure close to the minimum energy in order to greatly reduce the time of the further more accurate calculations. Secondly (optimization 2), the LANL2DZ basis set was used, with the “int=ultrafine scf=conv=9” additional key words, this is a superior basis set, and so gives a better optimization; due to its high accuracy pseudo-potential, which allows it better deal with heavy atoms. The third and final optimization (optimization 3) was used to account for the hypervalent phosphorous, with low lying d atomic orbitals. To do this the word “extrabasis” was added to the calculation file, and relevant information put into the end of the .gjf file.

A summary of the calculations is shown below.

| - | Optimization 1 Trans | Optimization 2 Trans | Optimization 3 Trans | Optimization 1 Cis | Optimization 2 Cis | Optimization 3 Cis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log | .log | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2MB | LANL2DZ | Gen | LANL2MB | LANL2DZ | Gen |

| Energy / a.u. | -617.5220479 | -623.576031 | -623.692912 | -617.5250179 | -623.5770719 | -623.6941561 |

| Energy / kJ/mol | -1621304 | -1637199 | -1637506 | -1621311 | -1637202 | -1637509 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.00003561 | 0.00004002 | 0.00005594 | 0.00007139 | 0.0000067 | 0.00001232 |

| Dipole Moment / debye | 0 | 0.3025 | 0.071 | 8.4621 | 1.3097 | 0.2292 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 | C1 | C1 | C1 | C1 |

| Calculation Time | 8min 20.9 sec | 52min 56.0 sec | 32min 38.1 sec | 13min 40.5 sec | 74min 59.9 sec | 41min 22.9 sec |

| Output File | DOI:/10042/to-7526 | DOI:/10042/to-7529 | DOI:/10042/to-7530 | DOI:/10042/to-7527 | DOI:/10042/to-7528 | DOI:/10042/to-7531 |

All RMS Gradient Norm's are less than 0.0001 a.u., showing that all calculations converged successfully. As expected after each optimization the energy of each complex fell, this confirms that each optimization step has found a more stable structure than the previous (which is also shown by the decreasing dipole moment in each case). It should be noted that each optimization step took longer on the cis isomer than the trans.

The trans isomer was found to be 3kJ/mol higher in energy than the cis isomer, however, with an error of about 10kJ/mol in these energies, these results are not reliable enough to confirm which of the two isomers is the more stable. The trans isomer has been found to be the lower energy thermodynamic product,[4], with the cis isomer the kinetic product, this is due to the differences in steric bulk and dipole moments. The more sterically bulky PCl3 groups will be moved as far apart as possible (trans relationship) in order to mimize the steric strain within the complex; the dipole moment is also lower in the trans isomer (0.071) than the cis isomer (0.2292), further stabilising the trans isomer (the dipole moments in the trans isomer cancel each other out). Using these arguements it is possible to alter to the complex inorder to favour either the trans or cis isomers; increasing the steric bulk of the group on the phosphorus increases the steric strain (favouring the trans isomer), and by changing the electronegativity of these groups the dipole moment can be altered (with a more electronegative group increasing the dipole moment, favouring the trans isomer).

Structural Analysis

The bond distances and angles of the optimized structures were measured and compared to literature (cis[3] and trans[5]).

| Trans Isomer | Cis Isomer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Literature | Calculated | Literature | |

| Bond Distances / Å | ||||

| Mo - P1 | 2.42(222) | 2.500 | 2.47(615) | 2.576 |

| Mo - P2 | 2.42(222) | 2.47(715) | 2.577 | |

| Mo - C1 | 2.05(702) | 2.016 | 2.02(072) | 1.972 |

| Mo - C2 | 2.05(589) | 2.005 | 2.02(072) | 1.973 |

| Mo - C3 | 2.05(702) | 2.05(471) | 2.059 | |

| Mo - C4 | 2.05(744) | 2.05(744) | 2.022 | |

| P1 - Cl1 (Ph) | 2.11(752) | 1.840 | 2.11(447) | 1.837 |

| P1 - Cl2 (Ph) | 2.11(868) | 1.828 | 2.11(802) | 1.823 |

| P 1- Cl3 (Ph) | 2.11(868) | 1.854 | 2.11(861) | 1.854 |

| C1 - O1 | 1.17(444) | 1.164 | 1.17(636) | 1.158 |

| C2 - O2 | 1.17(528) | 1.165 | 1.17(636) | 1.149 |

| C3 - O3 | 1.17(444) | 1.17(479) | 1.136 | |

| C4 - O4 | 1.17(377) | 1.17(479) | 1.137 | |

| Angle / ᵒ | ||||

| P1 - Mo - P2 | 176.7(42) | 180.000 | 94.2(89) | 104.620 |

| P1 - Mo - C1 | 90.0(23) | 92.000 | 92.1(73) | 94.000 |

| P1 - Mo - C2 | 88.3(70) | 87.200 | 89.3(76) | 90.300 |

| P1 - Mo - C3 | 90.0(25) | 175.8(17) | 163.700 | |

| P1 - Mo - C4 | 91.6(29) | 88.7(18) | 80.600 | |

| C1 - Mo - C2 | 90.7(84) | 92.100 | 87.0(39) | 83.000 |

| C1 - Mo - C3 | 178.4(34) | 180.000 | 89.9(27) | 87.000 |

| C1 - Mo - C4 | 89.2(17) | 180.000 | 89.1(23) | 90.100 |

(it was found that the cis P1 - Mo - C1/C3 angles were assigned the wrong way round in literature and so they have been corrected above, also the trans C1 - Mo - C4 angle has been wrongly assigned as 180ᵒ when it should be around 90ᵒ)

These results show that the calculated Gaussian structures correspond well with those formed by synthesis, suggesting that the substitution of the Ph groups with Cl on the phosporous did not have much of an effect on the complex. The Mo-P bonds are longer in the cis isomer than the trans, this is due to the elongation of the Mo-P bonds in the cis isomer inorder to minimize the unfavourable streic interactions between the bulky Cl (and Ph) substituents. The bond lengths and angles are slightly different for the equatorial and axial postions, this is likely to be due to a distortion from octahedral to relieve the steric strain caused by the bulky PR3 groups.

The bond angles in the cis isomer are not a particuarly good match to those in literature, shown by the P - Mo - P angle being 10ᵒ less than that expected from literature. This is possibly due to the replacement of the Ph groups with chlorines; but more likely that a local and not the global miminum of this strcutre has been found, a different basis set or pseudo-potential could be used to try and correct this.

Vibrational Frequency Analysis

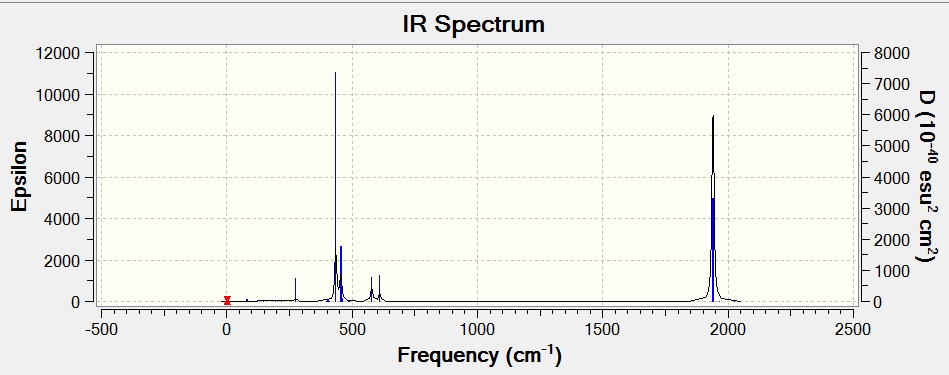

A vibrational frequency analysis was carried out to confirm the optimized geometry was at a minimum.

| - | Trans Frequency | Cis Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | Gen | Gen |

| Energy / a.u. | -623.692912 | -623.6941561 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.00005613 | 0.00001227 |

| Dipole Moment / debye | 0.0721 | 0.2292 |

| Calculation Time | 35min 16 sec | 35min 5.5 sec |

| Output File | DOI:/10042/to-7538 | DOI:/10042/to-7537 |

As the above results show the frequency results are valid as the same complex energy and dipole moments were calculated to be the same as for the geometry optimization.

| Optimized Trans | DOI:/10042/to-7537 | Optimized Cis | DOI:/10042/to-7538 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Frequencies (cm-1) | Lowest "Real" Normal Frequencies (cm-1) | Low Frequencies (cm-1) | Lowest "Real" Normal Frequencies (cm-1) |

| -2(.2868) | 4(.5769) | -1(.2774) | 11(.7521) |

| -1(.9674) | 7(.0091) | -0(.0002) | 20(.279) |

| -0(.0005) | 40(.4796) | 0(.0003) | 45(.8822) |

| -0(.0004) | - | 0(.0005) | - |

| -(0.0002) | - | 0(.8097) | - |

| 2(.8571) | - | 1(.9519) | - |

The "Real" frequencies are all positive which confirms that the optimized structure is a minimum on the potential energy curve and not a maximum (transition state). The "low frequencies" are all very close to zero, which shows the accuracy of the method and basis set used for these calculations.

Low Frequencies

| Vibration Number | Vibration Jmol | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans 1 | 4(.44) | 0(.0547) | In phase rocking of the PCl3 groups, out of phase to the rocking of the Mo(CO)4 unit. | |

| Trans 2 | 6(.97) | 0(.0000) | Out of phase rocking of the PCl3 groups, with no motion of the Mo(CO)4 unit. | |

| Cis 1 | 11(.73) | 0(.0163) | Out of phase rocking of the PCl3 groups, with slight motion in the Mo(CO)4 unit. | |

| Cis 2 | 20(.28) | 0(.0042) | Different out of phase rocking of the PCl3 groups, with slight motion in the Mo(CO)4 unit. |

These low frequency vibrations are due to the low amplitude rocking of the molecules. Only very small energies are required to cause these motions, as energy is proportional to frequency (E=hf), therefore these rocking motions will be present at room temperature.

Stretching Frequencies of C=O

The C=O stretching frequencies calculated by Gaussian were compared to the experimental values found in literature[6].

| Gaussian IR Frequency / cm-1 | Literature Value / cm-1 | Gaussian Intensity | Symmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans | 1 | 2025(.51) | - | 5(.3729) | A1g |

| 2 | 1966(.85) | - | 5(.9353) | B1g | |

| 3 | 1939(.90) | 1896 | 1605(.9860) | Eu | |

| 4 | 1939(.19) | 1896 | 1605(.5838) | Eu | |

| Cis | 1 | 2019(.11) | 2072 | 1604(.8249) | A1 |

| 2 | 1952(.34) | 2004 | 813(.3376) | A1 | |

| 3 | 1941(.49) | 1994 | 588(.4071) | B1 | |

| 4 | 1938(.06) | 1986 | 544(.6079) | B2 |

It can be seen that the calculated frequencies match up well to those from literature[6]. There are slight differences between the values because of the poor ability of Gaussian to include backbonding effects, and because of the 10% error in the anharmonic terms in the calculations.

It can be seen that four carbonyl stretches are calculated for each complex, but all four peaks are only observed on the spectrum for the cis isomer. This is because on for the trans isomer (where only one peak is visible) two of the peaks have such low relative intensity (5 compared to 1605) that they do appear on the spectra, and the other two peaks are degenerate, thus appearing at the same frequency and forming just a single peak. This shows that gaussian is able to predict (with reasonably high accuracy) vibrational frequencies that are not observable using experimental techniques.

Mini Project

Introduction

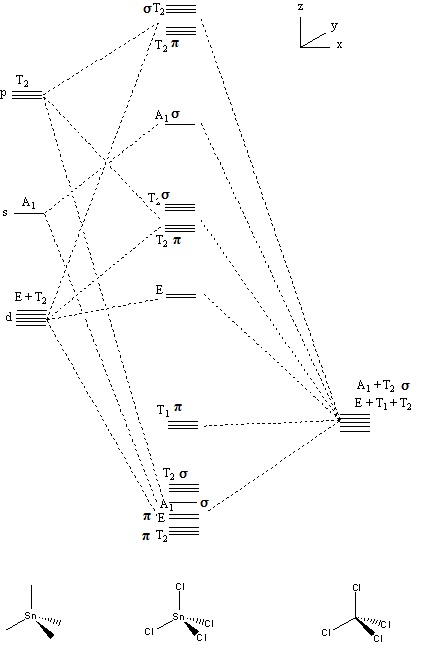

In this mini project the structures of SnCl4, SnI4 and SnMe4 will be optimized and their properties calculated and discussed.

Optimizied Strcutures:

Optimization

First the structure of each molecule was optimized, all using the B3LYP method and set to a tetrahedral starting geometry in order to find the global and not a local minimum. However, different basis sets were used to account for the heavy atoms present in the molecules. Tin tetrachloride and tin tetraiodide are both made up entirely of heavy atoms, and so the LANL2DZ basis set was used on all atoms within them. Tin tetramethyl, however, contains carbon and hydrogen atoms that are not heavy atoms (unlike tin), so in this case the "Gen" basis set was used. The gen basis set was set up to use the LANL2DZ (pseudo potentials) on tin, and the more simple 6-311G basis set on the carbon and hydrogen atoms.

All subsequent analysis was carried out using the same basis sets as in the optimization step, so the results are comparable (same potential surface). Ideally the same basis sets would be used on all the molecules to give a better energy comparison, as this is sensitive to the method and basis sets used.

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ | Gen |

| Energy / a.u. | -63.3149153 | -49.06015167 | -163.0871417 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.00007374 | 0.00000078 | 0.00001868 |

| Dipole Moment | 0 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Point Group | TD | TD | C1 |

| Calculation Time | 0min 19.6sec | 0min 32.0sec | 14min 14.9sec |

| Output Files | DOI:/10042/to-7654 | DOI:/10042/to-7655 | DOI:/10042/to-7656 |

All "RMS Gradient Norm" are less than 0.0001, showing that all calculations converged successfully, showing a mimimum has was calculated. It should be noted that while SnCl4 and SnI4 remained tetrahedral, SnMe4 has the C1 point gorup. Due to the change of atoms in each case it is not possible to compare the energies.

Bond Lengths and Angles

The bond lengths and angles from the optimized geometries were compared to those from literature[7][8][9].

| SnCl4 | Literature[7] | SnI4 | Literature[8]. | SnMe4 | Literature[9] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Length / Å | Sn - R | 2.37(017) | 2.280(2) - 2.279(3) | 2.75(723) | 2.69 | 2.15(51) | 2.102(8) - 2.138(6) |

| Bond Anlge / ᵒ | R - Sn - R | 109.4(71) | 108.63(10) - 110.07(12) | 109.4(71) | - | 109.438 - 109.518 | 109.3(2) - 109.6(2) |

The calculated results are seen to correspond well with the experimental results from literature. This shows that Gaussian is an accurate tool for calculating the structure of a molecule.

The calculated bond lengths fit the expected results. The more electronegative Cl has a shorter Sn-R bond length than that of I, and the smaller atomic radii C has a shorter bond length than the larger Cl. All of the calcualted bond lengths are slightly longer than the literature values, this shows the error in the calculations, to improve on this a more accurate method and basis set could be used.

The bond angles calculated show SnCl4 and SnI4 to be perfectly tetrahedral with all bond angles equal, and SnMe4 to be distorted with bond angles varying by 0.3ᵒ (almost perfect tetrahedral. This is because of the larger methyl groups taking up a bigger physical area and so sterics distort the strcutre slightly.

Both the literature bond lengths and angles are over a range, while the calculated results are a specific value, this is expected to be due to calculations being run on a stationary single molecule, rather than a crystal structure with motion.

Vibrational Frequency Analysis

Frequency analysis was carried out using the same method and basis sets as used for the optimization calculations. It was found that all vibrational frequencies were positive, showing that the optimized geometry was indeed at a minimum.

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .fch | .fch | .fch |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | FREQ | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ | GEN |

| Energy / a.u. | -63.3149153 | -49.06015167 | -163.0871418 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.00007369 | 0.00000071 | 0.0000187 |

| Dipole Moment | 0 | 0 | 0.002 |

| Output File | DOI:/10042/to-7657 | DOI:/10042/to-7658 | DOI:/10042/to-7659 |

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency / cm-1 | Frequency / cm-1 | Frequency / cm-1 |

| 88(.4365) | 41(.9987) | 81(.3591) |

| 88(.4365) | 41(.9987) | 90(.2849) |

| 117(.0496) | 60(.7474) | 96(.0334) |

The vibrational modes for each molecule are shown below (using SnCl4 to show each vibration).

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Frequency / cm-1 | Intensity | Vibration (Cl) | |

| 1 | 88(.44) | 0(.0000) | 42(.00) | 0(.0000) | 133(.77) | 0(.0351) | |

| 2 | 88(.44) | 0(.0000) | 42(.00) | 0(.0000) | 134(.18) | 0(.0269) | |

| 3 | 117(.05) | 16(.6579) | 60(.75) | 2(.0141) | 143(.95) | 6(.3065) | |

| 4 | 117(.05) | 16(.6579) | 60(.75) | 2(.0141) | 144(.72) | 6(.3672) | |

| 5 | 117(.05) | 16(.6579) | 60(.75) | 2(.0141) | 146(.27) | 6(.4160) | |

| 6 | 513(.71) | 0(.0000) | 130(.81) | 0(.0000) | 482(.18) | 0(.0001) | |

| 7 | 367(.32) | 46(.4975) | 199(.13) | 33(.7023) | 505(.52) | 30(.8398) | |

| 8 | 367(.32) | 46(.4975) | 199(.13) | 33(.7023) | 505(.89) | 30(.7936) | |

| 9 | 367(.32) | 46(.4975) | 199(.13) | 33(.7023) | 506(.53) | 31(.0482) |

9 vibrations can be seen, showing that these vibrations have followed the 3N-6 rule (SnMe3 has more vibrations not shown here due to the hydrogens). As expected the stretching frequency increases as the R group gets lighter (Me>Cl>I), as predicted by the laws of simple harmonic motion.

The vibrations for SnCl4 and SnI4 are identical, because they have the same symmetry, with the same IR inactive vibrations (1, 2 and 6). However, in SnMe4 these vibrations are slightly IR active , though so small that they would never be seen on an experimental IR spectrum. This is because of the slightly distorted tetrahedral strtructe of SnMe3 (as shown by the bond angles), which causes the vibrations to not be perfectly symmetrical (although no difference can be seen by human eye compared to the corresponding vibrations in SnCl4). This argument also explains why the sets of degenerate vibrations in SnCl4 and SnI4 are not degenerate in SnMe4.

Molecular Orbital Analysis

The molecular orbitals (HOMO -1, HOMO, LUMO, LUMO +1) were calculated for each molecule, again using the same method and basis set as for the optimization.

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO -1 |  |

|

|

| HOMO |  |

|

|

| LUMO |  |

|

|

| LUMO +1 |  |

|

|

Output files: DOI:/10042/to-7835 , DOI:/10042/to-7836 , DOI:/10042/to-7837

These MO's show the close relationship in structure (and reactivity) of SnCl4 and SnI4, and their difference to SnMe4. It can be seen that in the HOMO regions of SnCl3 and SnI3 all the electron density is based on the electronegative halide atoms, with increasing electron density on the more electropositive tin in the LUMO.

NBO Analysis

An NBO analysis was carried out to show the charge distribution over each molecule.

| SnCl4 | SnI4 | SnMe4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sn | 1.073 | 0.491 | 1.233 |

| R | -0.268 | -0.123 | -0.715 |

| H | - | - | 0.136 |

It can be seen that, as expected, the more electronegative chlorine atoms have a greater negative charge than the equivalent iodine atoms. The charge distribution on the SnMe3 is not quite as expected, with a higher negative charge than predicted on the carbon atoms.

Conclusion

This computational lab course has shown how computational chemistry can be used to model many compounds to high levels of accuracy. It is able to optimize compounds to mimimum energy geometries, and confirm it is a minimum using frequency analysis, as well as calculate vibrational modes, bond lengths and angles, point groups, dipole moments, molecular orbitals and natural bond orders of a molecule.

Computational chemistry is a relativlty new area and so has its limitations, but with extended research into the area it is constantly improving and becoming a much more powerful (and accurate) tool.

References

- ↑ Kuchitsu, K. J. Chem. Phys.', 1968, 49, 4456 [1]

- ↑ Glaser, J. Johansson, G. Acta Chemica Scandinavica, 1982, A 36, 125-135 [2]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cotton, F. et al. Inorg. Chem., 1982, 21(1), 294-299. [3] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "mocomplex" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Darensbourg, D. Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18(1), 14-17. [4]

- ↑ Hogarth, G. Norman, T. Inorg. Chim. Acta 254, 1997, 167-171. [5]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cotton, F. Inorg. Chem., 1964, 3(5), 702-711. [6]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Reuter, H. Pawlak, R. Zeitschrift fur anorganische und allgemenine Chemie, 1999, 624(4), 925-929 [7] Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "bom" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 Meller, F. Fankuchen, I. Acta Cryst., 1955, 8, 343 [8]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Krebs, B. Henkel, G. Dartmann, M. Acta Cryst., 1989, C45, 1010-1012 [9]