Rep:Mod2:albertagain

BH3

Optimisation of BH3

From the optimisation of BH3, the following was obtained:

| B-H Bond Distance | 1.19 Å |

| H-B-H Bond Angle | 120.0o |

| File Type | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | B3LYP |

| Basis Set | 3-21G |

| Energy | -70 189 kJ/mol or -26.4623 A.U. |

| Point Group | D3h |

| Job Time | 10.0 seconds |

From literature [1], the average B-H bond distance is 1.21Å while the H-B-H bond angle is 120.1o which reflects the trigonal planar geometry of BH3 which corresponds to the bond distance and bond angle obtained from Gaussian. The job time refers to the number of iterations required to generate the log file for the optimisation of BH3. The longer the job time, the more the iterations required which suggests that either the chosen Gaussian method is too complex or the molecule chosen is too large. The energy in atomic units is rounded to 4 decimal places to reflect the accuracy from the conversion of atomic units to kJ/mol. However, when comparing energy in atomic units between more than one molecule, the exact value obtained from Gaussian should be used for comparison due to the fact that 1 A.U. is equivalent to 2652.4 kJ/mol or accurate to 0.0004 A.U.

In the optimisation of BH3, the following structures were obtained:

For structures 1 and 2, Gaussian generated both structures without the B-H bonds. The absence of the B-H bonds in structures 1 and 2 is not because no bonds exist between B-atom and H-atoms but rather the B-H bond distance in structures 1 and 2 are too far apart or have exceeded a range for the B-H bond distance such that Gaussian assumes B and H as independent atoms instead.

MO Representation of BH3

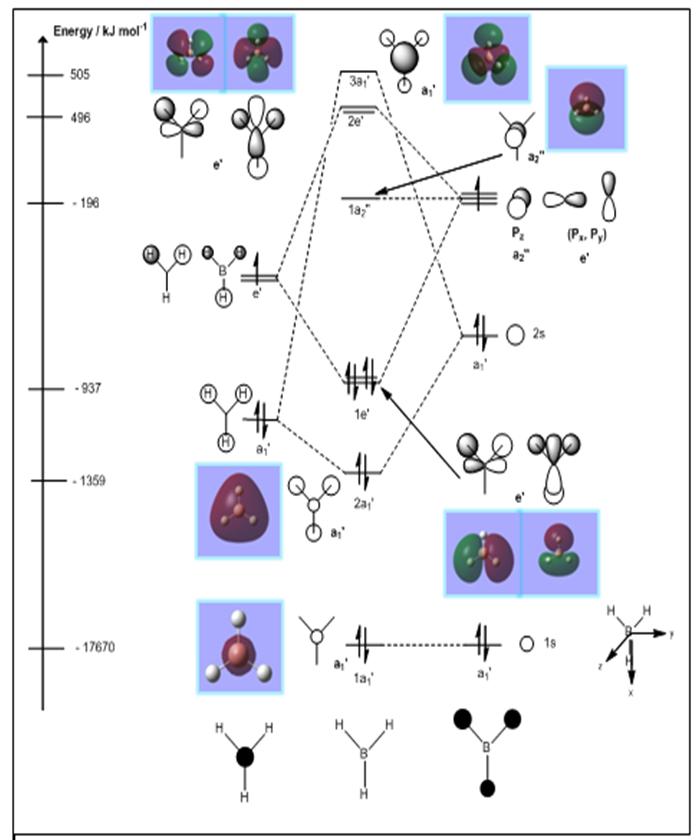

The MO diagram below was referenced from molecular orbital diagram for BH3 and reproduced with the addition of occupied and LUMO orbitals from Gaussian. The reals MOs obtained from Gaussian for BH3 can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2578 .

Comparing the real and LCAO MOs from the above diagram, there are hardly any differences in terms of electron cloud density consideration for both MOs. However what is not captured in the real MO is the individual orbital contribution from the atoms to the real MOs.

Qualitative MO theory based on symmetry considerations of orbitals is adequate in deciding the appropriate and relevant orbital interactions and mixings. However, to exactly pin point the energies of each MO so as to align the MOs according to their actual energies is rather difficult as we would require the individual orbital wavefunction for such a determination. One good example is from the above MO diagram, 3a1' is placed above 2e' because of a higher energy. However on closer scrutiny of both energies, we see that in actual fact, both energies are relatively close to each other which may result in the position of 3a1' and 2e' to interchange in a theoretical approach as observed from the molecular orbital diagram for BH3.

BH3 Vibrations

The intensity for structure 4 is zero as in structure 4 the dipoles effectively cancel each other out resulting in a zero net dipole moment. As such, the peak pertaining to frequency 2598 cm-1 for structure 4 was not present on the IR spectrum on Gaussian.

Boron trichloride, BCl3

Optimisation of BCl3

| Calculation Method | B3LYP |

| Basis Set | LANL2MB |

| Job Time | 14.0 seconds |

| B-Cl Bond Distance | 1.87 Å |

| Cl-B-Cl Bond Angle | 120.0o |

| Point Group | D3h |

Frequency analysis, which is the second derivative of the potential energy surface, was performed to ensure that there would not be any negative frequencies which would otherwise result in an error in subsequent calculations with the log file for the optimised structure of BCl3. The frequency analysis will also allow for the determination of whether the structure drawn is really the structure with the minimum energy. From the output of the frequency analysis, if the frequencies are all positive then we have a minimum, if one of them is negative we have a transition state, and if any more are negative then there is no critical point and the optimisation has not completed or has failed. Frequency analysis also serves as an important part in vibrational (IR and Raman) analysis of a molecule. The same method and basis set has to therefore be used for both calculations so that the comparison between both calculations, in particular the frequency analysis, can be a fair comparison.

From literature [2] the bond angle for BCl3 is 120o which corresponds to the bond angle obtained from Gausian while the equilibrium B-Cl bond distance in BCl3 is 1.75Å which does not correspond to the bond distance obtained from Gaussian. One interesting point to note about the bond distance obtained from Gaussian is that the value corresponds to the bond distance for BCl3- instead of BCl3. This difference in B-H bond length could be due to different experimental conditions in determining the averaged B-H bond length.

In some structures (see earlier section on optimisation of BF3), Gaussian does not capture bonds as the distance between the atoms are considered to be too far apart or have exceeded a certain range for the bond length between two atoms such that Gaussian assumes that the atoms exist as stand-alone, independent atoms where in reality there exists a bond between the atoms.

A chemical bond is the energy or a force that holds two or more atoms together in a molecule or compound. There are many types of chemical bonds such as covalent bond, ionic bond, van der waals forces and hydrogen bonding. In a given reaction, bonds will break and form depending on the energy required to first break the bond where bond breaking is an process endothermic while bond forming is an exothermic process.

The symmetry of boron trichloride, BCl3 from ground state should adopt a trigonal planar, D3h symmetry point group which corresponds to the symmetry point group obtained from Gaussian suggesting that Gaussian takes VSEPR theory into consideration as well.

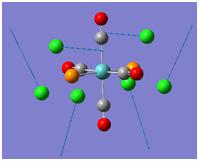

Organometallic Complex, Isomers of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Comparing Relative Energies

From the optimised ground state for cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-2546 and the optimised ground state for trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-2545 , the following data was obtained:

| Properties | cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | Trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| File Type | .log | .log | ||||||

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | ||||||

| Basis Set | LANL2DZ | LANL2DZ | ||||||

| Energy | - 623.5771 A.U. or - 1 637 187 kJ/mol | -623.5760 or - 1 637 185 kJ mol | ||||||

| Dipole moment | 1.3104 | 0.3044 Debye | ||||||

| Point Group | C1 | C1 | ||||||

| Job Time | 2 hours 58 minutes | 1 hour 37 minutes | ||||||

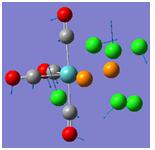

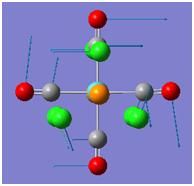

| Molecule Structure |

|

|

Comparing the energies obtained for the cis and trans structure of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 from Gaussian, the cis isomer obtained a slightly lower energy of 1637185 kJ/mol while for the trans isomer, the energy obtained is 1637187 kJ/mol though this difference is very minimal which could be due to the small Cl substituent on the phosphorous group. From the energy consideration for Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2, it can be concluded that the cis isomer is the more stable isomer. Nevertheless in consideration of dipole moments and steric effects, for the trans isomer, the overall net dipole moment is zero as the dipole moments cancel out and as such the trans isomer is thus predicted to be the more stable isomer for molecules with larger phosphorus substituent such as PPh3.

From literature [3], the trans-isomer of [Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] is thermodynamically more stable than its cis-isomer due to the enhanced steric bulk effects of the adjacent bulky PPh3 substituents in the cis-isomer. From experimental investigation of thermal isomerisation of cis-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] to trans-[Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] from literature [4], the trans-isomer required a reflux of 30 minutes in toluene while the cis-isomer only required a reflux of 15 minutes suggesting that the cis-isomer is the kinetic product while the trans-isomer is the thermodynamic product as a thermodynamic product is obtained through equilibrating conditions and requires a higher temperature or prolonged heating. This suggests that the trans isomer of [Mo(CO)4(PL3)2]where L is a bulky substitutent will be more favoured.

Comparing Vibrational Frequencies for cis and trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

From the frequency analysis of the optimised ground state for cis Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-2556 and the frequency analysis of optimised ground state for trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 DOI:10042/to-2557 the following very low frequencies for each of the cis and trans isomer was obtained as shown in the table below:

The above vibrations occur at low frequencies. Since frequency is proportional to energy according to the equation E = hf, the above vibrations are also occuring at low energies. From literature [5] low frequency vibrational modes are observed as the ground state of the molecule is significantly depopulated at room temperature. In addition, as the vibrational potentials are anharmonic, this decreases the energy spacing between the energy levels, and hence low frequencies are observed.

Comparing Vibrational Frequencies for Carbonyl ligand for Cis and Trans Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

The tables below show the comparison of the IR frequencies for the carbonyl ligand for both the cis and trans isomers obtained from Gaussian and from literature [6]

| IR Frequency (Gaussian) | Intensity | IR Frequency (Literature) [6] | Synmmetry C1 Point Group [6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 763 | 1986 | B2 |

| 1949 | 1498 | 1994 | B1 |

| 1958 | 633 | 2004 | A1 |

| 2023 | 598 | 2072 | A1 |

From the above table for the cis isomer, the number of bands and frequency of the bands predicted from Gaussian corresponds to both the number and frequencies of the bands from literature [6] .

| IR Frequency (Gaussian) | Intensity | IR Frequency (Literature) [6] | Synmmetry C1 Point Group [6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 763 | 1475 | Eu |

| 1951 | 1498 | 1467 | Eu |

| 1977 | 0 | - | A1g |

| 2031 | 4 | - | A1g |

From the above table for the trans isomer, only two of the degenerate bands with symmetry point group Eu predicted from Gaussian corresponded with literature [6]. The remaining two bands predicted from Gaussian obtained a low intensity resulting in the absence of similar peaks from literature[6]. This suggests that computational chemistry is able to identify vibrational frequencies that would otherwise not be observed through experimental investigation thereby providing a more comprehensive analysis of the molecule in question.

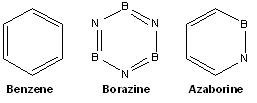

Project: A computational study of Benzene, Borazine and Azaborine

Introduction

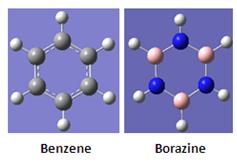

Borazine or commonly refered to as the "inorganic benzene" is an example of a 6π-electron, 6 membered ring system. The cyclic delocalisation, as observed in benzene, is reduced in borazine due to the large electronegative difference between boron and nitrogen. This difference in polarity results in borazine to show a different reactivity pattern from benzine. While borazine is expected to undergo addition reactions, however literature studies [7] have shown that borazine can also undergo electrophilic aromatic substitutions just like its organic counterpart in the gas phase.

Azaborine is isostructural and isoelectronic to borazine and benzene. From a recent literature review [8] azaborine is comparatively more aromatic than borazine but less aromatic than benzene but undergoes electrophilic aromatic substitution just like benzene.

The aims of this project hope to investigate (a) a comparative aromaticity study between benzene and borazine in the gas-phase (b) a comparision of the BN vibrational stretching frequencies across borazine and azaborine (c) electrophilic aromatic substitution with a comparison to mechanistic explanations, molecular orbitals and energy considerations for azaborine derivatives.

Optimisation of Benzene, Borazine and Azaborine

The optimisation of benzene and borazine were performed using opt+freq option, DFT, method = B3LYP, basis set = 3-21G and NBO = full nbo. The optimised structure for benzene can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2579 while the optimised structure for borazine can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2582 .

For azaborine, the optimisation was performed using optimisation, DFT, method = B3LYP, basis set = 3-21G and can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2581 . From literature [9], the computational study of azaborine used a medium-sized basis set of 6-31+G(d, p) which is appropriate for relatively small molecules like azaborine. Although the literature also used the basis set of 6-31+G(3d, 2p) for subsequent optimisations for further analysis, however due to limitations in time, the optimisation for azaborine for vibrational analysis was performed using the medium-sized basis set of 6-31+G(d, p) and can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2587 .

Aromatic study of Benzene and Borazine in Gas-phase

From Gaussian, it is observed that borazine does not have delocalised electrons as compared to its benzene counterpart. For Gaussian, bonds are shown based on the distance between atoms. However, in reality, bonding encompasses electronic interactions and density which Gaussian does not take into account. For borazine, it is more polar than benzene due to a large electronegative difference between boron and nitrogenm and as such the electron delocalisation as observed in benzene is therefore not observed for borazine in Gaussian due to localised lone pairs in borazine.

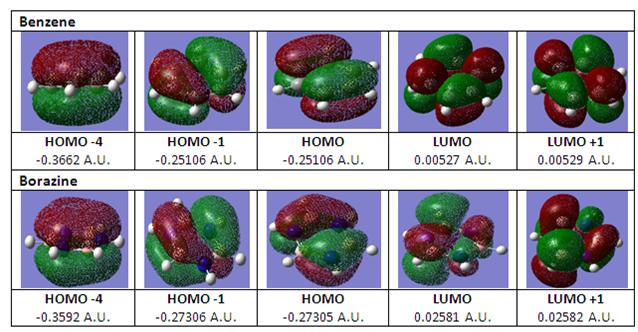

From literature [7], in order to further analyse whether borazine is aromatic, the aromatic stabilisation energies (ASE) should be considered. However as this consideration requires a study of the energy fluctuation across a reaction as well as protonated molecules, the comparison of the MOs between benzene and borazine was performed instead to provide some evidence of aromaticity in borazine. The MOs for benzene can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2589 while the MOs for borazine can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2590 .

Comparing with the HOMOs and LUMOs from the above diagram, there is a large similarity between the HOMOs and LUMOs for both benzene and borazine. For the MOs in benzene, it can be observed that the orbital lobes are of similar sizes but for borazine, the orbital lobes are of different sizes due to the difference in electronegativity between boron and nitrogen. Comparing HOMO-4 for both benzene and borazine, it can be observed that there is a cyclic delocalised п-electron cloud that forms the priory for an aromatic system. As such, it can be concluded that borazine is an aromatic system but is less aromatic than benzene due to a slighly more diffused electron cloud for borazine which is supported by literature [7] where the aromatic stabilised energy for borazine is half that of benzene.

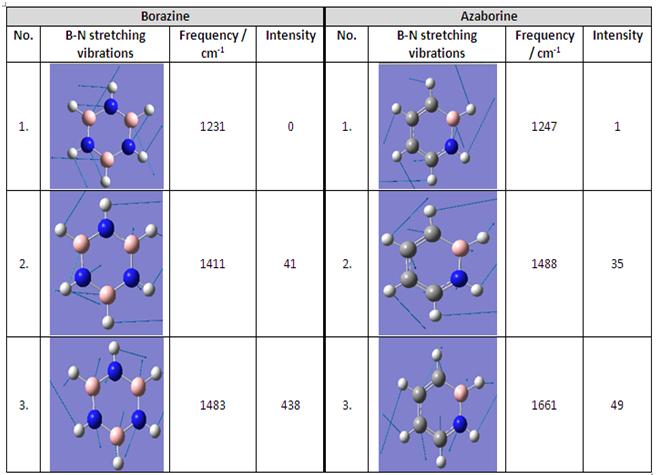

Vibrational Frequencies of B-N for Borazine and Azaborine

From literature, [10] borazine undergoes electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions in the gas phase. The table below shows the vibrational frequencies for borazine and azaborine with relatively similar motions.

From literature [11], the B-N stretching frequency for borazine is 1465 - 1330 cm-1 while from literature [12]the B-N stretching frequency for azaborine is 1613 cm-1, 1533 cm-1, 1453 cm-1, 1427 cm-1 and 1350 cm-1. The vibrational frequencies obtained from Gaussian for borazine and azaborine correspond well with that of their respective literature values. It is however observed that the B-N stretching vibrational frequencies for similar motions for azaborine is much higher than that in borazine suggesting that the B-N bond is stronger in azaborine than in borazine which thereby suggests that azaborine is aromatically more stable than borazine as supported by literature [8] where the aromatic stabilisation energy of azaborine is comparable to that of benzene but is half that of benzene for borazine.

Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution on Borazine and Azaborine

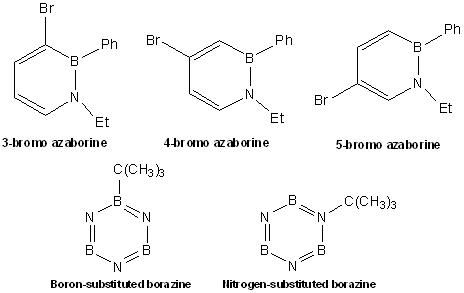

In order to determine the effects of electrophilic aromatic substitution for borazine and azaborine, the following borazine derivatives and azaborine derivatives were chosen and compared which can be obtained from DOI:10042/to-2613 for 3- bromo-substituted azaborine, DOI:10042/to-2614 for 4-bromo-substituted azaborine, DOI:10042/to-2634 for 5-bromo-substituted azaborine, DOI:10042/to-2602 for boron-substituted borazine and DOI:10042/to-2617 for nitrogen-substituted borazine.

Energy Comparison of boron and nitrogen-substituted borazine

The table below shows the energy comparison for boron and nitrogen-substituted borazine.

| Properties | boron-substituted | nitrogen-substituted |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (A.U.) | -397.77694672 | -397.75449659 |

| HOMO-LUMO Energy Gap (A.U.) | 0.29429 | 0.27836 |

From the above comparison, it can be deduced that for electrophilic aromatic substitution for gas-phase borazine, the nitrogen substituted compound is thermodynamically more stable than the boron-substituted as the electrophile will be more attracted to the electronegative nitrogen atom on borazine. Furthermore, as the nitrogen-substituted borazine compound has a smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gap, it suggests that it is more reactive than its boron-substituted counterpart.

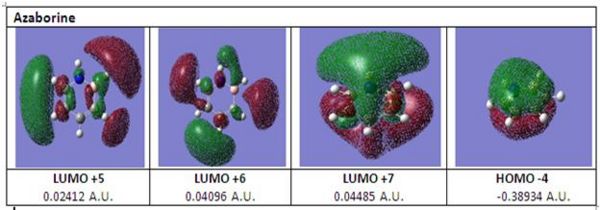

Molecular Orbital Analysis of Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution on Azaborine

The diagram below shows the HOMO and LUMOs of azaborine which can obtained from DOI:10042/to-2588 . From HOMO -4 of azaborine it can be deduced that azaborine has a cyclic delocalised π electron cloud thus showing that azaborine is aromatic. From LUMO +5 of azaborine, it can be observed that the orbital lobes are primarily centered around carbon-3 and carbon-5 but not on carbon-4. Furthermore, from LUMO +7 it is observed that the large electron cloud that forms the delocalised electron cloud for azaborine incorporates carbon-4 and not carbon-3 and carbon-5 of azaborine. Instead, there exist two separate lone orbitals for bonding interactions on carbon-3 and carbon-5 thereby favouring electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions on carbon-3 and 5 of azaborine.

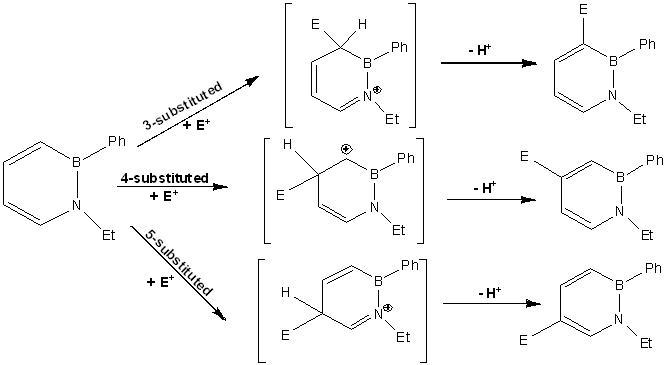

Wheland Intermediates of Azaborine

From the understanding of the Wheland intermediates for azaborine as shown below, the carbon 4-substituted azaborine is not the favoured position for electrophilic aromatic substitution as the positive charge on the intermediate is not stabilised by the electronegative nitrogen atom as observed in the carbon 3 and 5-substituted azaborine.

Taking into consideration both the molecular orbitals and the Wheland intermediates for azaborine, it can be concluded that the carbon 3 and 5-substituted azaborine is more favoured than carbon 4-substituted azaborine.

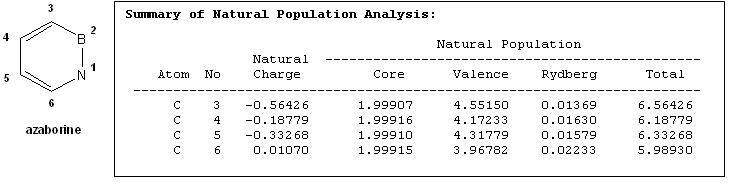

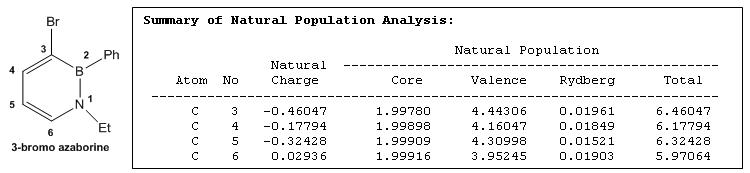

NBO Analysis of the Charges on Carbon atoms of Azaborine

The table below shows the charges on the carbon atoms of azaborine

From the table above, it is observed that carbon-3 has the most negative charge followed by carbon-5 suggesting that for electrophilic aromatic substitution on azaborine, carbon-3 substitution is more favoured than carbon-5 substitution. Carbon-4 is the least negative and as such is not favoured for electrophilic aromatic substitution as supported by molecular orbital, Wheland intermediate and energy comparison analysis as shown earlier.

Energy Comparison of carbon 3, 4 and 5-substituted Azaborine

The table below shows the energy comparison for 3, 4 and 5-substituted azaborine.

| Properties | carbon 3-substituted | carbon 4-substituted | carbon 5-substituted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (A.U.) | -3116.53457271 | -3116.53466492 | -3116.52957080 |

| HOMO-LUMO Energy Gap (A.U.) | 0.00116 | 0.00982 | 0.01221 |

Considering the energy considerations, carbon 4-substituted azaborine has has the most negative energy suggesting that carbon 4-substituted azaborine is the least reactive and the most stable of the three different azaborine derivatives. Hence carbon-4 substituted azaborines will not undergo subsequent electrophilic aromatic substitutent. The smaller the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, the softer is the molecule and the more reactive is the molecule. From the above table, carbon 3-substituted azaborines yielded a smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gap than carbon 4-substituted azaborines. This further suggests that electrophilic aromatic substitution is more favoured for carbon 3 and 5-substituted azaborines than carbon 4-substituted azaborines.

NBO Analysis of the Charges on Carbon atoms of Azaborine Derivatives

The table below shows the charges on the carbon atoms of azaborine derivatives

Comparing the charges on carbon-3 and carbon-4 for 3-bromo substituted azaborine and 4-bromo substituted azaborine, it is observed that for 3-bromo substituted azaborine despite an electronegative, electron-withdrawing Br-atom attached to carbon-3, its negative charge is still the most negative thus favouring subsequent electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. However, this same observation is not reflected for 4-bromo substituted azaborine where the negative charge on carbon-4 is not the most negative and as such will not be susceptible to further electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions. This suggests that a carbon-3 substituted azaborine is more favoured for electrophilic substitution than a carbon-4 substituted azaborine.

Conclusion

From this computational study, the aromaticity of borazine was confirmed through a molecular orbital analytical approach and for azaborine, it has allowed for a deeper understanding of the selective reactivity on azaborine for electrophilic aromatic substitution. A further research for this project is to perhaps consider whether does azaborine undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution in a polar solvent as a correlation to borazine.

References and Citations

- ↑ M. R. Hartman, J. J. Rush, T. J. Udovic, R. C. Bowman Jr and S. J. Hwang J. Solid State. Chem., 2007, 180, 1298 - 1305 DOI:10.1016/j.jssc.2007.01.031

- ↑ L. G. Christophorou and J. K. Olthoff, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data, 2002, 31, 971 - 988 DOI:10.1063/1.1504440

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, Inorg. Chem., 1979, 18, 14 - 17 DOI:10.1021/ic50191a003

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg and R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680 - 2682 DOI:10.1021/ic50187a062

- ↑ Y. C. Shen, P. C. Upadhya, and E. H. Linfield, Appl. Phys. Letters, 2003, 82, 2350 - 2352 DOI:10.1063/1.1565680

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 F. A. Cotton, Inorg. Chem., 1963, 3, 702 - 711 DOI:10.1021/ic50015a024

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 K. Boggavarapu, P. K. Ashwini and J. D. Eluvathingal, Inorg. Chem., 2001, 40, 3615 - 3618 DOI:10.1021/ic001394y

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 K. Prabhat, Chemcos, 2009, 4, 6 - 7 http://www.chemistry.iitd.ac.in/chemcos/issue-IV/pdf/infocus.pdf

- ↑ P. J. Silva and M. J. Ramos, J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74, 6120 - 6129 DOI:10.1021/jo900980d

- ↑ B. Chiavarino, M. E. Crestoni and S. Fornarini, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1999, 121, 2619 - 2620 DOI:10.1021/ja983799b

- ↑ G. Socrates, Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies, Third Edition, 2004, 247 - 253

- ↑ A. J. V. Marwitz, M. H. Matus, L. N. Zakharov, D. A. Dixon and S. H. Liu, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48, 973 - 977 DOI:10.1002/anie.200805554