Rep:Mod2:PorcupinePorridge

Edit at your peril

Module 2

Introductory Work - Analysis of BH3

Using GaussView (5.0.8c), a BH3 molecule was created from the molecular fragment panel, and the bond lengths were increased to 1.5Å. From here, using the DFT-B3LYP method and basis set 3-21G, the geometry was optimized.[1]

| Bond Length (Å) | 1.19 |

| Bond Angle (o) | 120.00 |

| Charge | 0.00 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Final Energy (Hartrees) | -26.4622 |

| RMS Gradient (Hartrees) | 0.0002 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.00 |

| Point Group | D3h |

3-21G is a low-level basis set and as such the accuracy of the resulting data can be low for large molecules. However BH3, being such a small and simple molecule, would not benefit much from a large basis-set, but the calculations would take up much more processor time regardless. As such the 3-21 basis set is optimal in this case. When you compare the resulting data to literature values [2] it is clear to see that the Gaussian data is very close, and accurate within the error boundaries of the calculations. The literature states that all the bond angles within BH3 are 120.00o as you would expect from having three identical atoms arranged around a point, and the calculations show this as well. The RMS value (obtained in atomic units (Hartrees)) clearly shows that the conformation reached by Gaussian is at a definite minimum, as it is close to zero and we can also tell that the geometry optimisation was successful, as the log file states the convergence of the displacements and the forces within the molecule.

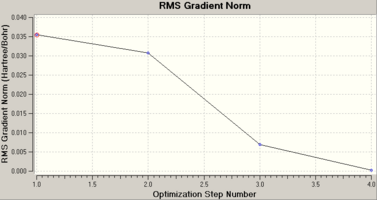

The optimization works by utilising a simplified form of the Schrödinger equation, using the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. As the distance been atoms changes, then energy within the molecule will decrease or increase. The most stable form of a molecule would have the atoms in such as position that the energy has been minimized. The minimum of the energy, or the equilibrium point, is the point at which a slight alteration in energy will not cause the position of the atoms to change. The software uses the given set of positions for the atoms, and works out the internal energy. It will then change the position of one of the atoms and calculate a new internal energy. If this energy is from a more stable conformation i.e. lower than the previous energy, the software then remembers this state, and continues this process of remembering the lowest energy conformations, until it cannot find a more stable state. The energy change of the system, compared to the structural alterations, is known as the RMS gradient, and when the RMS gradient is at its lowest value, a minimum has been found. Simply being told the energy values, and it can be easier to understand the optimisation process by looking at the graphs produced by Gaussian, during the calculations.

Vibrations of BH3

Using Gaussian to analyse the vibrational modes within a molecule gives us the ability to take into further consideration the obtained geometry. Infrared spectroscopy is based upon the vibrations within molecules, and as such, we are able to use Gaussian and it's vibrational analysis to predict the IR spectra of molecules. Also, we can use the vibrations given by the calculations, to see if the optimized geometry is correct. If the molecule is not in the real ground state of the molecule, then anomalous vibrations can be exhibited, such as those with negative frequencies.

To ensure that the optimisation had completed correctly, the energy of the molecule optimised normally was compared to the energy of the molecule from the vibrational calculations. As the energies were both -26.4622 Hartrees, we can be sure that the original optimisation was correct. Another method to check if the optimisations were correct is to compare the lowest frequencies, given in the log file. If these frequencies happened to be lower than the frequencies obtained from the vibrational analysis, then the optimisation was also successful. These low frequencies are due to the movement of the centre of mass within the molecule, and so should be the lowest frequencies calculated, let alone appear on the vibrational analysis[3].

Molecular Orbital Analysis of BH3

The already optimised structure of BH3 was then used to start the Gaussian energy calculations, again using the DFT/B3YLP method with the 3-21G basis set, with the pop=full and full NBO parameters. If a different method or basis set were to be used, the calculations could (and probably would) give a different ground state for the molecule, and so it would not be possible to compare results across the different operating parameters. Output file [4]

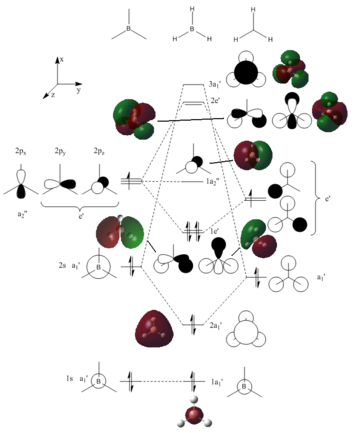

Using the basic orbital energies from above, and a common knowledge of MO diagrams, it was easy to make a simplified MO diagram for BH3. If an MO diagram was created without seeing the relative energies, especially the degenerate energies, it would be possible to make in incorrect MO diagram, with the 2e' levels being above the 3a1'. It would be rather difficult to predict this correct structure, as the energies of the levels are dictated by the interactions of s and p orbitals within the molecule. The image beneath is my MO diagram for the molecule, with molecular orbital images placed close to the respective bonds. If a separate basis set was to be used, then we may actually see a change in the respective placement of the levels and orbitals, as different basis sets can calculate different internal energies, for example placing the 3a1' level beneath the degenerate 2e' levels.

One problem with the comparison between the LCAO orbitals and the calculated orbitals is dimensions. We can draw the LCAO orbitals as if they were in a pseudo-3D form, but they are unreliable when we have the fully 3D, calculated orbitals. LCAO works when we don't have a better option, but they do help with create a quick and simple representation of molecular orbitals.

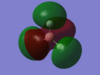

Electron Density of BH3

Using the output file from the above molecular orbital analysis, it was possible to see how Gaussian was considering the distribution of charge within the BH3 molecule[4]. Gaussian can represent the electron density using colours, and in their basic scale the more red the atom, the more negative, and the more green the atom the more positive. As you would expect to see, Gaussian has predicted that the Boron atom is more negative than the Hydrogen atoms.

The analysis shows Boron having having a charge of 0.332 and each Hydrogen atom having a charge of -0.111. We know the molecule to be neutral, so we know the software rounded the values up for the Hydrogen atoms. If we delve further into the .log file, we can see how the separate atoms donate electron density to the bonds. Each BH bond has a component from the Boron orbitals and another from the Hydrogen orbitals, and we can see in the file that the Boron component is 33%s character and 66%p character, indicating that the Boron is sp2 hybridised. As you can see in the MO diagram above, there should be a non-bonding p-orbital of the Boron, perpendicular to the plane of the molecule, and in the log file here, we can see that the orbital is indeed non-bonding, as the energy of both the suspect orbital and the empty p orbital in the .log file, have identical energy values.

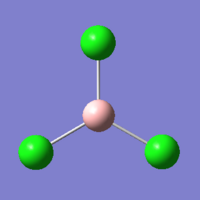

BCl3

BCl3 is similar to BH3 in that they share the same point group, but other than that, there are few similarities. For example, Chlorine is much heavier than Hydrogen and as such the vibrations within the BCl3 are different to those of the BH3. Due to the loss of simplicity from the change of the substituent Hydrogen atoms to Chlorine atoms, we needed to use a new basis set for the calculations. A bigger basis set is one that contains more functions with which to calculate internal energies.

| Bond Length (Å) | 1.87 |

| Bond Angle (o) | 120.00 |

| Charge | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet |

| Final Energy (Hartrees) | -69.4393 |

| RMS Gradient (Hartrees) | 0.0001 |

| Dipole Moment (D) | 0.00 |

| Point Group | D3h |

Larger or heavier molecules need larger basis sets to give data as accurate as a small basis set being used on a small molecule, and this increases the computational time and power needed. With the introduction of p orbitals on the substituent, the molecule becomes immediately becomes much harder to model from a quantum mechanical point of view, and as such, pseudo-potentials are used to simplify the electronic structure of Chlorine. Pseudo-potentials only take into account the valence electrons of the atoms, greatly reducing the number of possible interactions, and in turn reducing computing time. As before, a simple BCl3 molecule was created in Gaussview, but this time for the calculations, we had to incur extra constraints on the system - the molecule was constrained to only be within the D3h point group, and was only allowed to deviate from this symmetry by a tolerance of 0.0001. There was no need to alter the method used, and DFT/B3YLP was still used, and with the 'new' LanL2MB basis set.

When these calculated[5] values are compared to the literature [6], we can see that the bond lengths vary greatly and that the bond angles are very similar. Firstly, the calculated bond angle is sensibly 120o, however the literature states it to be 119.9o. This would mean that the molecule was no longer had the D3h point group, and that it had lost symmetry. Secondly, the literature bond length is stated to be 1.72Å, whilst the calculated length is a much different 1.87Å. Due to the low RMS value, we know taht we've successfully optimised the molecule and as such, must assume that the calculated results are not closer to the experimental data, as the basis set, or method might use some assumptions that were incorrect, giving us these discrepancies from the literature.

Comparing, BH3 to the BCl3 we get the relative bond lengths that we would've expected to see. Chlorine, being much larger and massive than Hydrogen, has a longer bond length to Boron than the Hydrogen. This is easily explained by the fact that larger atoms are unable to get closer to a point, due to increased repulsive forces. We'd also expect the bond angles to the the same, and if we compare the computational data, we can see that they are.

BCl3 Vibrational Analysis

The previously optimised structure was used again, to calculate the vibrations within the BCl3, again using the DFT/B3YLP method and LanL2MB basis set, with the pop=(full,nbo) parameter. We use the same parameters and basis set as before, again, to be able to compare the results from the previous data. Another use for the vibrational analysis is that it is a further analysis of the ground state. The initial optimisation of a system only works to the first derivative of the potential energy of the molecule. The vibrational calculations of Gaussian work to the second derivative and is a more accurate sign of whether we've truly found the ground state. If all the listed vibrations within the molecule are positive, then we have found the minimum energy of the system. Plus, the final energy of the system was identical to that from the optimisation, and so the original optimisation was correct[7] .

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Diagram |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Frequency (cm-1) | 214.13 | 214.13 | 376.94 | 417.38 | 939.47 | 939.47 |

| Literature[6] Freq. (cm-1) | ~249 | ~249 | 455 | n/a | ~956 | ~956 |

| Intensity | 3.93 | 3.93 | 43.78 | 0.00 | 258.69 | 258.69 |

| Symmetry | E' | E' | A2'' | A1' | E' | E' |

As we can see from comparing the literature frequencies with the calculated frequencies, there are some large discrepancies. The calculated frequency for each vibration is always smaller than the respective literature value, and this would be indicative of a gap in the Gaussian calculations i.e. a force not being taken into account. Also, we see no experimental value for the A1' symmetric stretch, as it is completely symmetric, reducing the intensity of any vibrations to 0.

The calculation times for these Gaussian jobs were rather low - opt@9.0 seconds cpu time, vib@19.0 seconds cpu time. The calculation times were low due to the small basis sets used, as well as the structure being already optimised, for the vibrational job.

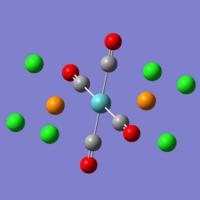

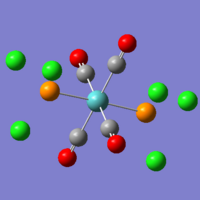

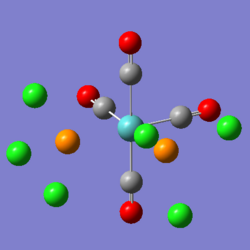

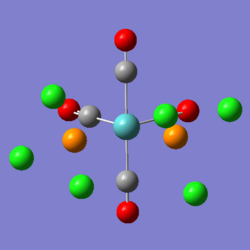

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

The Gaussian software is not limited to light elements - and can be used to accurately predict the geometry of heavier elements, such as transition metals. For this project, we decided to look at the conformations of the Mo(CO)4L2 system (i.e. cis/trans) and compare the vibrations and internal geometry/energy of the isomers. The two complexes differ by the arrangement of the two L ligands - if they are opposite each other, with respect to the Molybdenum centre, then the molecule is trans, and if the two groups are at 90o to each other - then the molecule is cis. The two different isomers have different point groups - with the trans isomer being D4h and the cis isomer being C2v, and due to them having different symmetry, they will also generate very different vibrational spectra. As we saw above, the symmetry of a molecule can reduce the number of IR active vibrations - this is due to the change in dipole moment during a vibration. If there was no change in the dipole, then the intensity of the vibration in the IR spectrum, is nil. If, due to asymmetry, the vibrations cause a change in dipole, we do see a respective peak in the IR. The greater the change in dipole, the greater the intensity of IR vibration seen. Due to a centre of inversion within the trans molecule, the number of carbonyl absorption bands is only one, whilst in the cis isomer, we've 4 carbonyl peaks.

To be able to check calculated data against the theory, we'll be looking at the molecule Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2, and it's isomers. The early in our degree, we looked at the molecule Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2, and if we were able to model this, then we could compare the calculated values against our own experimental data. However, the intricacy of the Ph substituents greatly increases the difficulty of the calculations, wasting large amounts of computational time.

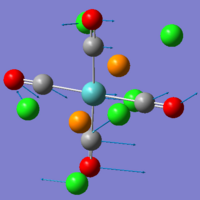

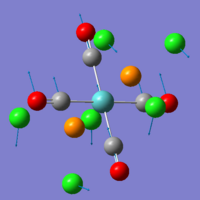

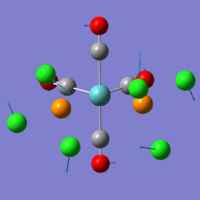

Initial Optimisation of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

As with the previous molecules, the isomers were created using Gaussview, and were initially optimised using DFT/B3YLP with the LanL2MB basis set and the new parameter 'opt=loose'. Only one molecule was created - the file was copied, and each of the two files was a different isomer - made by using the the dihedral bond tool, and they underwent separate calculations. This process was just for an initial optimisation as the complexity of the molecule means that sending it off to the scan cluster whilst unoptimised, and using a large basis set with no alterations, would be a large waste of processor time. As such, the parameter 'opt=loose' is used to get a rough approximation of the structure in the first place. These first optimisations[8][9] are then used again, and optimised under a new basis set - LanL2DZ (a more powerful basis set due to including better pseudo-potentials) and with the parameter 'opt=loose' replaced with 'con=ultrafine scf=conver=9' - giving us new, better optimised output files [10][11].

On the left you can see the result from the first optimisation of the trans isomer. The central metal ion is planar with the carbonyl groups, and the PCl3 groups are at ~180o to each other. The chlorine atoms have placed themselves in what would be expected to be the most stable conformation - with the dihedral angle between any of the chlorine substituents being 60o. The data from this initial optimisation is not of much use, as we then optimised this structure further (after rotating the bonds of the PCl3 groups, as per the guide). What you can see however, is that some of the bonds are not drawn within these images - the bonds that involve the phosphorus atom. This is because the idea of being able to see a bond is a human concept - not one of the physical world, and Gaussian performs its calculations by looking at the placement and interactions of atoms - ignoring the man-made idea of being able to see bonds. Gaussian is set to understand that only certain bond lengths can exist, and the instant that the atoms may be 0.000001Å larger than the limit - it does not visualise a bond as actually existing, despite the bonding interactions still being there.

On the right, you can see the structure of the trans isomer, once the second optimisation (using the LanL2DZ basis set and 'con=ultrafine scf=conver=9' parameters) had finished. The calculations are more accurate, and so it is now worth comparing the calculated data. Beneath, are also two images from the two optimisations of the cis isomer, using the same conditions as the trans isomer. As you can see, there is practically no change in the conformation of the molecule between the first and second optimisations.

|

|

It was hard to obtain comparable experimental data for the Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 isomers, and as such, the best data available was for the Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 molecule instead. Despite being a different molecule, the difference between experimental and calculated data was quite low (bar one or two large differences). The most likely reason for these wildly differing values is that the molecules are indeed different, but it may also be partly due to the assumptions and approximations made within the Gaussian calculations. Some of the differences can be accounted for, just by comparing the difference in molecular structure. For example, the large discrepancy in the P-Mo-P bond angles, for the cis isomer, are due to the steric bulk of the substituents on the phosphorus atoms. Obviously, the phenyl groups are more bulky than single chlorine atoms, and so the two phosphorus atoms cannot get as close to each other, when bonded to phenyl rather than chlorine - increasing the P-Mo-P bond angle.

| Trans Isomer | Cis Isomer | |

| Charge | 0 | 0 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet |

| Total Energy (kJ/mol) | -1637198 | -1637201 |

| RMS Gradient (Hartrees) | 0.00003 | 0.0000 |

| Dipole Moment (Debyes) | 0.3047 | 1.3106 |

| Point Group | C1 | C1 |

As you can see, the data relative energies of the isomers are very similar, and the cis isomer is slightly more favourable - which is not exactly as you'd expect, due to the increased steric hindrance between the bulky PCl3 groups within the cis isomer, supposedly raising the energy of the cis isomer to above that of the trans isomer. However, due to the accuracy of the Gaussian calculations being circa 10 kJ/mol, and the energies only being 3kJ/mol apart, it is easily possible that the trans isomer is the more stable one, and that the calculations are too rough in their approximations.

Vibrational Analysis of Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2

Using the secondly-optimised output files, the internal vibrations of the molecules were calculated[12][13], for comparison. All of the settings within the Gaussian calculation window were kept the same, except the job type. As no negative vibrational frequencies were observed, it is safe to assume that the optimised structures used so far, are the ground states of the isomers. There were multiple low-frequency vibrations of the isomers, which are very low energy, and will therefore be barely populated at room temperature - and as such will probably not be detected in an IR spectrum. However, the lowest vibrational bands for the trans isomer seem to be wrong, as the frequencies are much higher (5 times higher) than the low frequencies of the cis isomer, and considering how the cis isomer shows clean vibrations at these levels, I suspect the trans isomer vibrations of being incorrect. However, there are no negative vibrations for either molecule and as such, the trans isomer being used is in the ground state. If that is so, then why is there this discrepancy?

The other vibrations of interest are the carbonyl vibrations, as can be seen below.

| Diagram |  |

|

|

|

| Frequency (cm-1) | 1802.66 | 1807.15 | 1827.78 | 1877.77 |

| Intensity | 1292 | 1299 | 10 | 0.43 |

| Symmetry | Eu | Eu | A1g | A1g |

| Diagram |  |

|

|

|

| Frequency (cm-1) | 1945.29 | 1948.61 | 1958.33 | 2023.27 |

| Intensity | 763 | 1498 | 632 | 598 |

| Symmetry | B2 | B1 | A1 | A1 |

The proposed number of IR visible vibrations are confirmed by the above data. For the trans isomer, due to the centre of inversion, we would expect to see 1 band. The calculations show that there are 4 different vibrations, as is expected. Two of the vibrations has very low intensities (due to an almost negligible change on the dipole moment of the molecule), and the two remaining visible bands are at very similar frequencies, and considering the symmetry again, these two bands should be identical. The remaining vibration bands could easily overlap in an experimental spectrum, and so only 1 band would be seen. There are 4 active carbonyl vibrations in the cis isomer, as we expected, but again, due to the close proximity of two of the bands, only 3 may be visible on a spectrum. The comparison between an experimental spectrum and calculated values, can be problematic due to the method by which Gaussian calculates the vibrations. Current experimental spectra are gathered by creating a mull of the sample, placing it between KBr plates, and then obtaining a spectra. Gaussian does not take into account any solvent or conditions of the spectra, and predicts the vibrations as if the sample were in the gas phase. This can cause quite a large shift between any literature values and calculated values.

Accuracy of Calculations

As highlighted earlier, the accuracy of the energy calculations is around 10 kJ/mol, which is respectable considering the order of magnitude of the energies obtained. Most data has been presented to a reasonable degree of accuracy - but in some cases, this is not needed due to the nature of the data e.g the vibrational data cannot be accurately compared to experimental data, and so a high degree of accuracy was not actually required.

- ↑ Log file for initial BH3 geometry optimization; https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:ROSS_BH3_OPT.LOG

- ↑ V. Horvath, I. Hargittai, Structural Chemistry,2004, 15, 3, 233. DOI:10.1023/B:STUC.0000021532.01536.21

- ↑ Log file for BH3 vibrational analysis; https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:ROSS_BH3_FREQ.LOG

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chk file for MO analysis of BH3; https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:ROSS_BH3_MO.CHK

- ↑ Log file for initial optimisation of BCl3; https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:ROSS_BCL3_OPT.LOG

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 O. Brieux de Mandirola, Spect. Acta, 1967, 23A, 4, 767 DOI:10.1016/0584-8539(67)80004-7

- ↑ Log file for BCl3 vibrational analysis; https://www.ch.imperial.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Image:ROSS_BCL3_VIB.LOG

- ↑ Log file for the first optimisation of cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-3995

- ↑ Log file for the first optimisation of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-3998

- ↑ Log file for the second optimisation of cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-4000

- ↑ Log file for the second optimisation of trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-4001

- ↑ Log file for vibrational analysis of doubly optimised cis-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-4002

- ↑ Log file for vibrational analysis of doubly optimised trans-Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2; DOI:10042/to-4003