Rep:Mod1:pkm

Third Year Computational Lab: Module 1

Modelling using Molecular Dynamics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

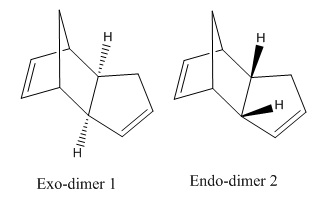

Dimerisation of cyclopentadiene occurs via Diels- Alder which is a concerted cycloaddition between the diene and the dienophile. The two new C-C bonds are formed simultaneously, and therefore this reaction is stereospecific, with respect to the dienophile and the transition state is highly ordered.

The geometry in which the dienophile approaches the diene gives rise to two possible stereoisomers: exo-isomer where the substituents on dienophile point away from the diene; or the endo- isomer in which the substituents point towards the diene.

To determine the energies of the exo-(1) and endo-(2) products, they were drawn in ChemBio3D and their geometries were optimised using MM2 force field which effectively minimised their energies. The relative stabilities of the two products are shown in Table 1:

|

The lowest energy simulated for exo-dimer was 31.88kcalmol-1 (133.39kJmol-1) and for the endo-dimer was 34.01kcalmol-1 (142.31kJmol-1).

From the optimisation, endo- product is shown to be 2.13kcalmol-1 higher in energy compared to the exo- one. However endo-dimer is formed in majority[1], meaning that the reaction is kinetically controlled rather than thermodynamically, in which case the lowest energy stereoisomer would form as major product. This leads to a conclusion that the endo transition state is in a lower energy than that of the exo- isomer and therefore the kinetic product, i.e. endo- stereoisomer predominates.

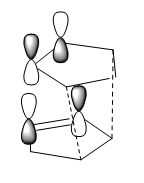

This can be explained by secondary orbital interaction which is present only in the endo transtion state, not the exo one. [2] This is the interaction between the HOMO of the diene and the LUMO of the denophile giving rise to extra stability and therefore lowering the transition state energy.

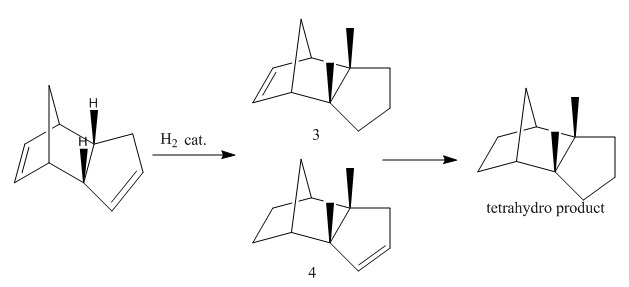

When the cyclopentadiene dimer (molecule 2) is hydrogenated, either one of the double bonds can be hydrogenated resulting in isomers 3 and 4. Tetrahydro product will form over prolong hydrogenation. Energies of these two isomers were minimised using MM2 force field and compared in a similar fashion as before.

Table 2 Comparison of energy for molecule 3 and 4

|

From table 2, isomer 4 is 5.72kcalmol-1 lower in energy compared to isomer 3, meaning that isomer 4 is a more stable conformer and therefore the thermodynamic product.

The relative contributions from stretching, bending, torsion, van der Waals and hydrogen-bonding were anaylsed.

Bending and torsion are the main terms which contribute the most to the energies of the two isomers. For both cases isomer 3 has higher contributions than isomer 4. The higher bending and torsion strain of isomer 3 is due to the fact that the double bond is within the 6-membered cyclic ring with the bridgehead group, causing the double bond to lengthen and therefore becomes weaker. As a result, under thermodynamic control, the double bond in dimerised cyclopentadiene on the 6-membered ring will be hydrogenated more easily compared to that in the 5-membered ring since the strain associated with the 6-membered ring is higher than the 5 membered ring, and the release of strain is favourable in a system.[3]

Both isomers have similar contribution from stretching term, meaning that the bond lengths generated from the calculation resemble that of the ideal situation.

The intermolecular 1,4 VDW term does not show significant contribution to the overall energies of the molecules meaning that there is not a great deal of steric interaction in both molecules. This is true because there is no bulky groups present.

The non-1,4 VDW term relates to hydrogen bonding and contributes little to the overall energy of the two isomers. In fact it shows stabilising effect since both the values are in negative sense, meaning that there is some hydrogen-bond stabilising effect going on in the molecules. However this effect is very little since there is no O,N or F present in the system.

In all cases, isomer 3 has higher contributions from each of the terms and therefore results in a higher overall energy compared to isomer 4 and therefore reflects that isomer 4 is indeed the thermodynamic product.

Results of minimised models after subjection to MM2 force field

|

|

|

|

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

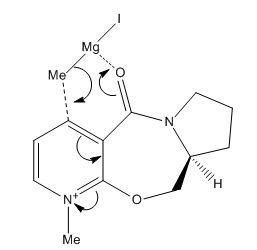

Reaction of Pyridinium Ring in N-methyl Pyridoxazepinone (5) with Grignard Reagent (MgMeI)

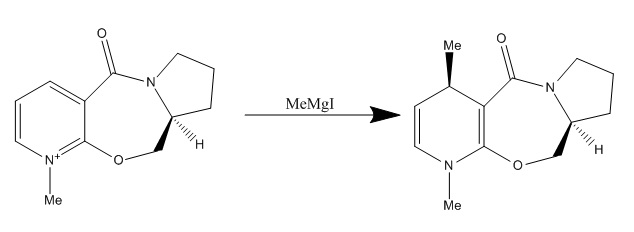

For complex molecule like this, the calculation does not work when MgMeI is included since magnesium atom is not recognisable by ChemBio3D. Besides, molecular mechanics does not account for bond breaking and forming and so will not be able to deal with two molecules in any one go.

The stereochemistry outcome of product 6 is governed by the mechanism involved between reactant 5 and the Grignard reagent and shows regio- and stereo- selectivity.

Mg-MeI reacts with reactant 5 in a concerted fashion where Mg coordinates to the amide carbonyl oxygen atom as shown in the figure below.

The structure of reactant 5 was drawn in ChemBio 3D and the positions of various atoms were manually altered by dragging them around in order to obtain the lowest energy structure. The Variation Principle states that the lowest energy corresponds to the most stable conformation. Therefore conformation 2 is the most stable conformation according to the MM2 calculations. C4-syn-alkylation is observed because the reactant is calculated to have the most stable conformation when the carbonyl oxygen has a dihedral angle of 12⁰ above the pyridium ring plane, and therefore forcing the coordination of Grignard reagent to occur on the same side. This leads to the delivery of Me group above C4 on the ring.[4]

Table 3 Components which contribute to energy of molecule 5 after MM2 energy minimisation

|

The structure was found to be most stable when the dihedral angle is at 12.0517° with an energy of 42.8701 kcalmol-1. Torsion and 1,4 VDW contribute the most of the overall energy meaning that there is strain present in the molecule due to ring structure; and that steric interaction within the molecule is high due to the complexity of the molecule with various substituents and functionalities.

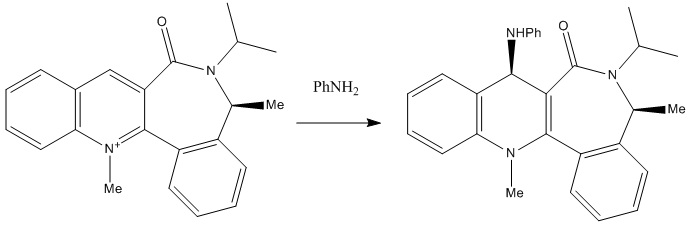

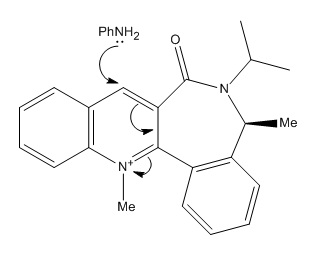

Reaction of Pydridinium Ring in N-methyl Quinolinium Salt 7 with Aniline

The analysis for this reaction is similar to the one discussed above. Product 8, a secondary amine, is formed in a regio and stereo-specific manner. In this case, the amine reacts on the opposite face to C=O due to steric control leading to the diastereofacial selectivity[5]. The mechanism is shown below which governs the stereo- outcome of product 8.

Table 4 Components which contribute to energy of molecule 7 after MM2 energy minimisation

|

The lowest energy conformer calculated was 66.3639kcalmol-1 with the dihedral angle of -21°. Negative dihedral angle corresponds to the fact that the carbonyl oxygen is pointing below the plane of the ring. The greater the dihedral angle in a negative sense, the more stable the conformation is. This will eventually reach a limit as the angle is increased further which will lead to higher energy conformation.

The carbonyl oxygen prefers to point below the plane of ring due to the presence of the methyl group which is pointing up. Steric interaction would increase if the oxygen points in the same direction as the methyl group and will result in a higher energy conformation which is not thermodynamically favourable.

Atropenantioselectivity, which is the prevention of rotation of bond due to the presence of large ring is shown in this example. C-C=O is very much responsible for the high stereoselectivity observed in product 8. The bulky NHPh group reacts on the opposite face, i.e. bottom face of ring, with respect to the carbonyl oxygen to avoid steric clash between the NHPh and the carbonyl groups.

The main contributing terms are the 1,4 VDW and bending due to the ring strain and sterics associated with the structures.

|

Improvements:

MM2 force field works efficiently and gives the results in a few seconds time instead of a few hours for geometry optimisation. The limitation of molecular mechanics is that it only involves the summation of independent terms relating to properties of molecules. It does not necessarily reflect accurate calculations and therefore MOPAC molecular orbital method can be used which accounts for the electronics of molecules and is more descriptive about the molecules and therefore leads to higher accuracy.

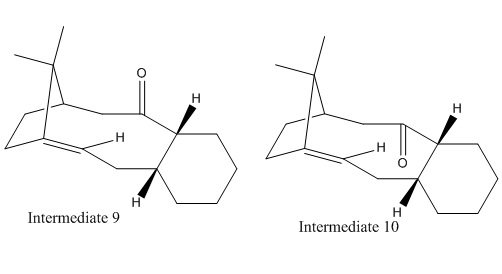

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Table 7 Terms contributing to total energy of Intermediates 9 and 10

| Terms/kcalmol-1 | Intermediate 9 | Intermediate 10 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.6145 | 2.4070 |

| Bend | 15.3647 | 12.047 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3933 | 0.2026 |

| Torsion | 20.1372 | 16.2244 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.2217 | -1.2575 |

| 1,4 VDW | 12.9730 | 12.1313 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1636 | 0.2633 |

| Total Energy | 50.4246 | 42.0181 |

Intermediate 9 shows noticeably higher bending and torsion strain compared to intermediate 10 and are the main factors which raises the total energy of intermediate of 9 due to ring strain associated with these complex molecules. 1,4 VDW also contributes significantly. This is due to steric interactions within the molecule, probably between the methyl groups on the bridgehead carbon and the carbonyl oxygen when the oxygen points up in intermediate 9. Intermediate 10 is about 8kcalmol-1 less in energy and more stable than intermediate 9. Therefore thermodynamically intermediate 9 would atropisomerise to intermediate 10 over time.

The concept of hyperstable olefin is used to explain the slow reactivity of the alkene present. Hyperstable olefin is defined as an alkene which contains less strain than the parent alkane.[6]

Its energy is lower than that of the parent alkane and so gives rise to negative olefin strain value, which is the difference in energies between the alkene and the lowest energy conformer of the parent alkane. The slowness is due to the steric hindrance arises from the methyl groups on the bridgedhead carbon which shield the double bond from being hydrogenated. The fact that the alkene is lower in energy compared to the parent alkane also disfavours the hydrogenation of the double bond to form the alkane which will be higher in energy.

MMFF94 produces results which are of higher energies than MM2, but the trend is still the same. Intermediate 9 still shows higher total energy compared to intermediate 10, which agrees with the analysis made above for MM2 results.

|

|

Modelling using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Part 1

First, the molecules were subjected to MM2 force field to optimise the geometry. Then the MOPAC method was applied which takes into account of the electronic wavefunction. From the HOMO diagram, the two alkenes can already be distinguished clearly. On the alkene which is syn to the C-Cl there is a large electron cloud (shown in red and blue) indicating high electron density and therefore higher nucleophilicity in that region.

Electrophilic addition of dichlorocarbene will occur on the HOMO orbital(C=C which is syn to the chlorine) since there is more electron density on the double bond region, as shown in the computed orbital diagram. On the other hand, the monoalkene is electron poor and does not have the electron cloud over the anti-alkene bond region and so will be less nucleophilic for electrophilic addition.

In the anti-alkene, the antiperiplanar stabilisation arises from π-orbital (HOMO-1) donation of electron density into σ*(C-Cl) (LUMO+1) and thereby stabilising (HOMO-1) relative to syn-alkene π-orbital (HOMO). The C=C in anti-alkene lengthens compared to syn-alkene as a result of the antiperiplanar interaction.[7]Therefore, electrophilic addition of dichlorocarbene occurs on the C=C double bond syn to the chlorine atom which does not experience this extra stabilisation.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

Part 2

Vibrations

In this part, Guassian interface density functional approach B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) was used to calculate and generate the infra red vibrational frequency data for the diene and monoalkene.

| Molecule | Syn C=C stretch | Anti C=C stretch | C-Cl stretch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diene (12) | 1757.45 | 1737.05 | 770.835 |

| Monoalkene (13) | / | 1758.06 | 774.96 |

From table 6, it can be seen that the stretching frequencies of C-Cl bonds in both the diene and monoalkene molecules match well with literature value, i.e. 780cm-1 for C-Cl.[8]

The bond length follows an inverse relationship with the energy of the bond, i.e. the shorter the bond, the higher the energy is associated with it. The higher energy associated then results in a higher vibrational frequency. From the results, the monoalkene shows slightly higher (4cm-1) calculated vibrational frequency compared to the diene. This means that C-Cl bond in monoalkene is shorter and at higher energy than the one in the diene.

The reported C=C stretching frequencies are about 100cm-1 higher than the literature value of 1620-1680cm-1.[9]

The stretching frequency of C-Cl and C=C in the anti-alkene is slightly higher than that of the diene (4.13 and 11.01cm-1 difference respectively). The higher the stretching frequency, the higher the bond energy is associated with it. This could be due to the additional stabilisation energy arises from the anti-periplanar interactions between σ*(C-Cl) and the π orbital and so raises the bond energy and therefore stretching frequency of anti-alkene.[10]

Structure based Mini Project using DFT-based Molecular Orbital Methods

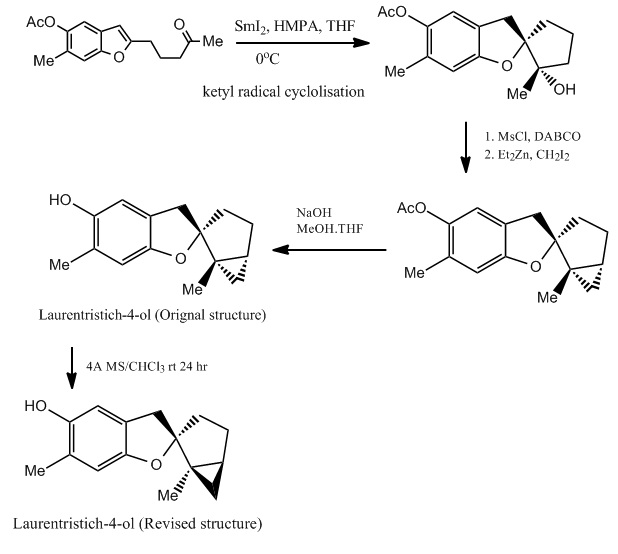

Synthesis and structural revision of Laurentristich-4-ol

Reaction Scheme

Mechanism

Due to the complexity of the reaction involves, only the few main steps which result in the regio- and stereo- selectivity were shown.

The starting material was treated with SmI2, which is at low valency, and HMPA, a polar aprotic solvent. Ketyl radical cyclisation results in a stereospecific cyclolised ring with methyl group pointing up and hydroxyl group pointing down. This intermediate is then dehydrated with methanesulfonyl chloride and DABCO, and treated with diethylzinc and diiodomethane in CH2Cl2 at room temperature, resulting in the cyclopropanation product. The stereoselectivity was suggested to be caused by the benzofuranyl oxygen which might have coordinated to diethylzinc and leads the cyclopropanation occur on the same side. NaOH was used finally to remove the AcO introduced as protecting group for alcohol on the benzylic ring. [11]

The absolute structure of the two isomers can be distinguished using NOESY experiments or X-ray crystal analysis.

The revised structure was discovered to have 1H NMR results different from that reported in literature.[12] It was found that after 1 month of slow isomerisation, the revised structure isomerised to the proposed structure of laurentristich-4-ol. This shows that the proposed structure of laurentristich-4-ol is thermodynamically more stable than the revised structure. This is supported by the calculated energy results from MM2 force field. The revised structure has an energy of 22.28kcalmol-1 whereas the proposed one has energy of 21.54kcalmol-1.

The exact mechanism for the rearrangement is still not known but presumably it occurs via ketyl radical cyclisation. By incorporating an isotopic label in the reactant the mechanism by which the reaction occurs can be investigated since the label can be traced in the product.

Reference:

P. Chen, J. Wang, K. Liu and C. Li, J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73 (1), 339–341 DOI:10.1021/jo7021247

J.Sun, D. Shi, M. Ma, S. Li, S. Wang, L. Han, Y. Yang, X. Fan, J. Shi and L. He, J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 915-919

Geometry optimisation

DFT-mpw1pw91/6-31g(d,p) method was used to optimise structures and energies for both structures. The outcomes are shown in the Jmol app.

|

|

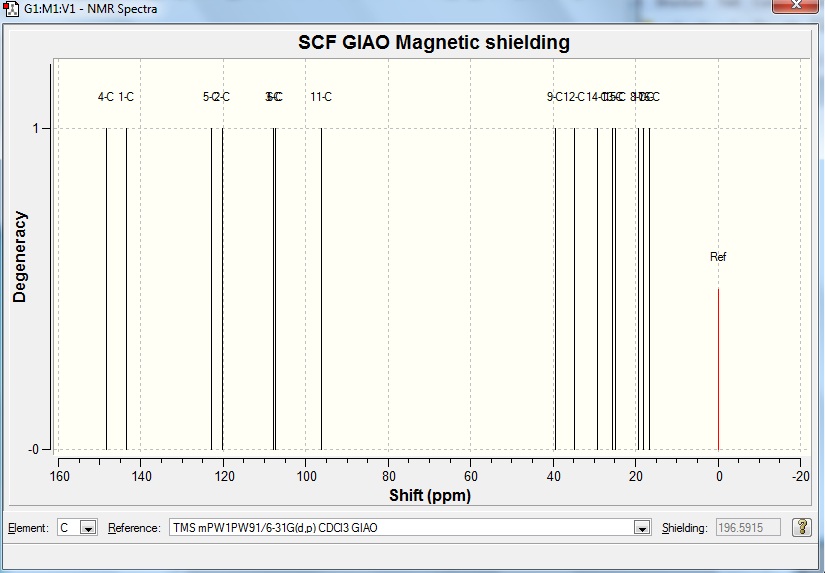

13C NMR spectrum prediction

Table 7 Results of experimental and calculated 13C NMR for proposed structure

|

Proposed structure DOI:10042/to-5685

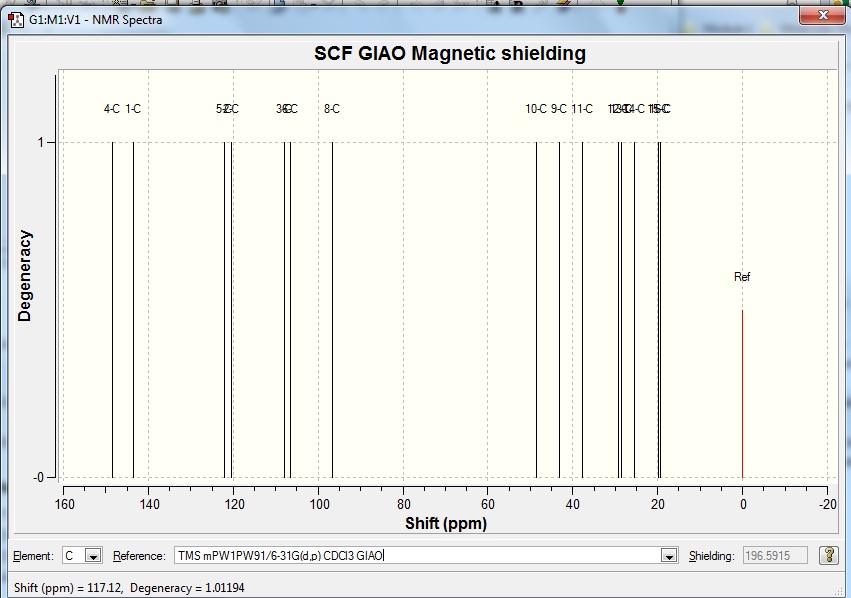

Table 8 Results of experimental and calculated 13C NMR for revised structure

|

Revised structureDOI:10042/to-5684

The computed results match well with the experimental results from literature. The values differ by about 5ppm at most and could be caused by the fact that the molecule which was input for the calculation might not have been optimised to the lowest possible energy conformer. Nonetheless the computational method is still powerful enough for chemists to predict the NMR results quite accurately.

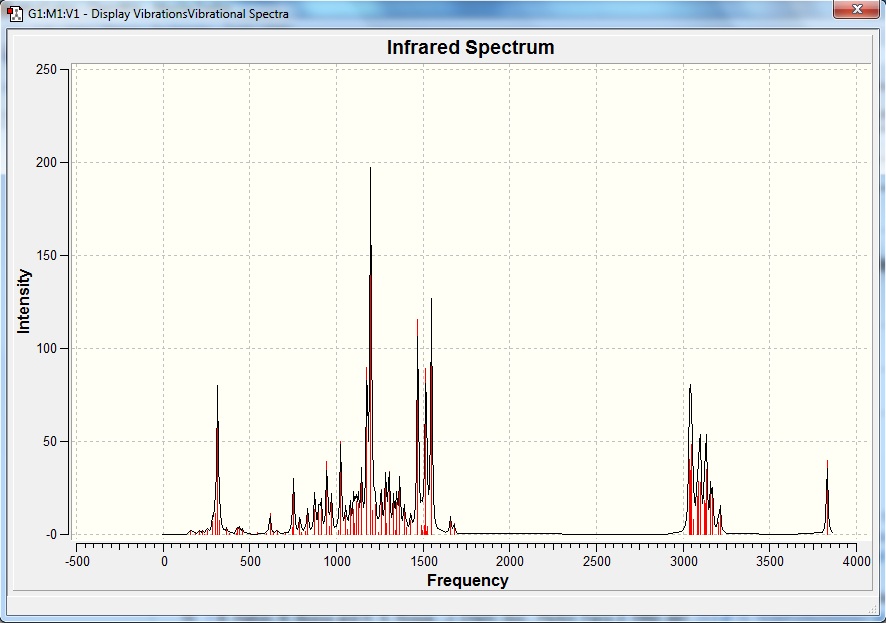

Predicting IR spectra for Laurentristich-4-ol

Since the two structures are stereoisomers they will have exactly the same number of the same types of bonds vibrating at very similar frequencies. This is supported by the graphs obtained from the simulation.

There is no literature IR frequencies reported in the journals so no comparison can be made with the experimental results.

The main peaks from the spectra were identified in table 9 below.

Table 9 IR peaks identified at vibrational frequencies

| Frequency /cm-1 | Bond |

|---|---|

| 3800 | O-H stretch in alcohol |

| 3000 | C-H stretch in alkane |

| 1600 | C=C stretch in aromatic ring |

| 1400 | C-H bend in alkane |

| 1200 | C-O stretch in alcohol |

| 1000 | C-H bend in alkene |

Reference

- ↑ Yano, T., Ozaki, S., Shigeko, S. and John, T. “J. Chem. Soft”, 1993, 1, 73-88

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ J.J. Zou, X. Zhang, J. Kong, L. Wang, "Fuel", 2008, 87, 3655DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2008.07.006

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ S. Leleu, C. Papamicaël, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Leavacher, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919 DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.V.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103 (8), pp 1891–1900 DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ G. Socrates, Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies, 3rd Edition, 2001, p. 65

- ↑ J. Coates, “Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach", Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, 2000)

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ P. Chen, J. Wang, K. Liu and C. Li, J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73 (1), 339–341 DOI:10.1021/jo7021247

- ↑ J.Sun, D. Shi, M. Ma, S. Li, S. Wang, L. Han, Y. Yang, X. Fan, J. Shi and L. He, J. Nat. Prod. 2005, 68, 915-919