Rep:Mod1:p.thakrar

Module 1 - Modelling Using Molecular Mechanics

The use of a computer to accurately model aspects of organic structure and reactivity is now a widely used technique. This type of modelling can be used to both rationalise the outcome and predict useful modifications or even new types of reaction. This can be useful in preventing the wasteage of resources if the reaction were to be carried out in the lab.

The tasks carried out here provide examples of the diversity of these molecular modelling techniques. The main points investigated are:

- The prediction of the geometry and regioselectivity of various reactions

- The use of semi-empirical and DFT molecular orbital theory

- The use of an institutional digital repository

The final part of the investigation involves research into the formation of isomer products of choice found from literature. Most organic synthetic reactions yield a mixture of isomers and various spectroscopic techniques including; NMR, IR and mass spectromety can be used to determine the formation of the correct isomer through molecular modelling techniques.

Hydrogenation of the Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerization

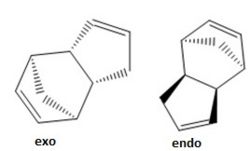

Two cyclopentadiene molecules can react via a Diels-Alder cycloaddition resulting in the formation of either an endo or exo dicyclopentadiene. The structure produced will be determined by the nature of the attack of the dienophile but at room temperature, the structure for the endo dimer is preferred over that of the exo dimer. The reaction proceeds as shown:

| Energy/kcal mol-1 | endo | exo |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.27 | 1.28 |

| Bend | 20.84 | 20.56 |

| Stretch-bend | -0.84 | -0.84 |

| Torsion | 9.51 | 7.67 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.56 | -1.43 |

| 1,4 VDW | 4.33 | 4.26 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| Total Energy | 34.00 | 31.89 |

The relative stabilities of the exo and endo dimers can be investigated by finding the total energy using the MM2 force field option found on ChemBio3D. This total energy takes into account the steric strain imposed on each of the

dimers thereby giving an indication into the more stable structure. Table 1 shows the various energies found in both structures along with the total energy following optimisation of the geometries. It was found that the endo geometry has a higher energy than the exo structure. This can be explained by considering the interactions between the bridged methyl group and the two out of plane hydrogen atoms. In the endo structure, the methyl group and the bridgehead carbons are all out of the plane and will experience an unfavourable interaction which is not found in the exo dimer.

Analysis of the different interactions in Table 1 shows that the most significant difference is in torsional strain between the endo and exo structures; with the exo geometry having a torsional strain 1.84 kcal/mol greater than that of the endo geometry. This can be explained by looking at the conformations of the groups around the newly formed carbon-carbon bond. As previously mentioned, the unfavourable interaction between the bridged methyl groups and the out of plane hydrogen atoms causes this difference in torsional energy.

However, it is the endo product that predominates when cyclopentadiene dimerises. This goes against what is observed in terms of energy and therefore indicates that the formation of the endo dimer is the kinetic product of the reaction.

The kinetic product considers the stability of the transition state and the thermodynamic product takes account of the product stability. Looking at the orientation of the cyclopentadiene structures in the transition states of both the endo and exo products along with the endo rule[1], enables further conformation of the endo product as the kinetic product. The endo rule states that the most stable transition state will be that containing the greatest secondary binding forces within the transition state. As shown in Fig. 3 the transition state for the endo product has four favourable interactions, compared to the two found in the exo product.

Hydrogenation

| Energy/kcal mol-1 | Molecule 3 | Molecule 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.24 | 1.09 |

| Bend | 18.97 | 14.55 |

| Stretch-bend | -0.76 | -0.55 |

| Torsion | 12.15 | 12.51 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.56 | -1.08 |

| 1,4 VDW | 5.73 | 4.50 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| Total Energy | 35.93 | 31.17 |

- Hydrogenation of the endo cyclopentadiene dimer results in the formation of two dihydro derivatives, as shown in Fig. 4. Only after prolonged hydrogenation, will the tetrahydro derivative be formed. The total energy, along with the other contributing energies, for the hydrogenation products can be found by running an MM2 calculation on ChemBio3D. The results can be seen in Table 2. Analysis of the data shows molecule 4 to be lower in energy than molecule 3 by 4.76 kcal/mol indicating that hydrogenating the cyclohexene double bond yields a more stable product than would be obtained when the cyclopentene ring is hydrogenated. Comparison of the total energy for hydrogenation with the total energy of dimerization for the endo product shows that energy is required for the formation of molecule 3 whereas energy would be released during the formation of molecule 4. The formation of the lowest energy product implies the formation of the thermodynamic product however this is not necessarily the case. In the dimerization of cyclopentadiene, the higher energy isomer is formed which indicates that the reaction definitely proceeds via kinetic control. However, in the hydrogenation process the lowest energy isomer is formed which could take place via either thermodynamic of kinetic control. It would not be accurate to say for certain via which process the product is formed without further consideration of the transition state.

- Comparison of the various interactions present within molecules 3 and 4 do not show any significant differences with the exception of bending. Here, a difference of 4.42 kcal/mol is observed, accounting for 93% of the difference between the total energies. This difference can be accounted for by the position of the double bond. In molecule 3, the double bond is part of a norbornene unit, resulting in a greater strain compared to the double bond found in the cyclopentene ring. Therefore, hydrogenation of the norbornene double bond will result in the greatest release of steric strain, once again indicating that this is the more stable thermodynamic product.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

Reaction of N-Methyl Pyridoxazepinone with a Grignard Reagent

The optically active derivative of prolinol reacts with a Grignard reagant (methyl magnesium iodide) to alkylate the pyridine ring in the 4-position. According to Shultz et al.[2] the high regio- and stereoselectivity for the addition of Grignard reagents to molecules such as N-Methyl Pyridoxazepinone may result from the coordination between the amide oxygen atom and the Grignard reagent. Taking this into account, a mechanism by which the reaction proceeds can be proposed as shown below:

The minimum energy of the reactant can be computed using the MM2 force field function found in ChemBio3D. The manual rearrangement of various atoms within the molecule was found to cause a further decrease in energy. Observation of the structure of the molecule suggests that very little flexbility will be present in the seven membered ring. This indicates that the structure will be stabilised by the orientation of the amide carbonyl group. Rearrangement of this group and measurement of the dihedral angle found between the carbonyl carbon and the benzene ring resulted in a further stabilisation. The process was repeated seven times yielding the conformation in Fig. 5. This particular conformer has a dihedral angle of 11.1o and an energy of 43.13 kcal/mol. The positive value of the dihedral angle indicates that the carbonyl group is above the ring. The magnesium in the Grignard reagent will coordinate to the oxygen via the lone pair resulting in the stereochemistry seen in the product (Fig 5.). For the energy minimisation calculation, the Grignard component was not included. This is because ChemBio 3D cannot support the structure of the molecule when the magnesium is present, resulting in an error if the calculation were to be attempted.

The structure of the lowest energy conformer can be seen by clicking this button:

Reaction of N-methyl Quinolinium Salt with Aniline

This reaction is similar to that above and involves the reaction of the pyridinium ring in the N-methyl Quinolinium Salt with aniline. The stereochemistry of the product can be explained by finding the lowest energy conformation for the reactant using the method detailed above. The reaction proceeds via the following mechanism:

The stereocontrol within the molecule can be explained by considering the reacting species. The nitrogen and oxygen are both electron rich species so the aniline will be repelled by the carbonyl group. Also, the orientation of the lone pairs is unfavourable and the lone pairs present on the oxygen in the salt and the nitrogen in aniline will result in a clash of the localised negative charges.

The repulsion between the atoms and the orientation of the carbonyl group will affect the way in which the aniline orientates itself with respect to the benzene ring. It was found that the lower energy configurations were those where the dihedral angle was negative, indicating that the carbonyl functional group is below the plane of the benzene rings. Alteration of the dihedral angle to - 19.5o resulted in a minimum energy of 62.60 kcal/mol. The negative dihedral angle indicates that the carbonyl group is underneath the benzene ring which will lead to aniline attacking on the top face, as observed in the product.

The structure of the lowest energy conformer can be seen by clicking this button:

A possible improvement that could be imposed to enhance the accuracy of the calculations would be the consideration of electronic effects and molecular orbitals. This can be done by carrying out the calculations using the MOPAC molecular orbital method or the PM6 method instead of the MM2 force field that was used. This would improve the accuracy of the energy and conformation of each of the investigated reactants.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

A key intermediate during the synthesis of Taxol, as proposed by Paquette, is initially synthesised with the carbonyl group pointing either up or down. Both of these isomers inter-convert and are therefore described as atropisomers - a conformer that can be isolated due to restricted rotation around a single bond. This means, carbonyl addition will be affected by the stability of the two isomers and will occur on the most stable isomer. The structure of each of the isomers can be seen below:

The energy of both isomers were calculated using the MM2 force field function. Again, the energy was further minimised by considering the geometry of the molecule and moving various atoms accordingly. For a six-membered ring, certain conformations such as the chair, boat and twist boat, will be favoured so these were taken into account. The table below details the energies for the atropisomers:

| Stretch | 2.81 | 2.73 |

| Bend | 16.50 | 15.87 |

| Stretch-bend | 0.45 | 0.35 |

| Torsion | 21.54 | 17.52 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -1.03 | 0.08 |

| 1,4 VDW | 14.11 | 12.82 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.13 | 0.06 |

| Total Energy | 54.51 | 49.43 |

Table 3 shows the most thermodynamically stable isomer to be the down isomer as it has the lowest energy. This can be attributed to unfavourable interactions between the carbonyl group and the out of plane hydrogen atoms or the bridge head methyl group. In the up isomer, the carbonyl group is pointing up and therefore experiences a steric clash with both the hydrogen atoms and the methyl group. However, in the down isomer the clash is avoided due to the orientation of the carbonyl group.

For this particular example, the energy was also calculated using the MMFF94 field. Again this showed the down isomer to be the most stable. The results from both calculations were very similar with a difference of 5.20 kcal/mol observed for MM2 force fields compared to 5.71 kcal/mol as observed for the MMFF94 calculation.

The alkene in both the isomers is known to be considerably unreactive and as a result reacts slowly. This could be down to the fact that it is a hyperstable alkene. According to Maier et al.[3] a hyperstable alkene is one which is less strained than the parent hydrocarbon and should show decreased reactivity due to the bridgehead location of the double bonds. The olefin strain energy can be used to interpret and predict the stability and reactivity of the bridgehead olefins. It is normally positive for most alkenes but in this case it is negative indicating that the atropisomers depicted in Fig. 7 should be less reactive than the unstrained olefins, as expected. The olefin strain energy can be calculated by subtracting the total strain energy of the most stable conformer of the parent hydrocarbon from the total strain energy of the most stable conformer of the olefin.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

All calculations thus far have been based on a purely mechanical molecular model. This section considers electronic interactions within the molecule and shows how electrons can influence bonds.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

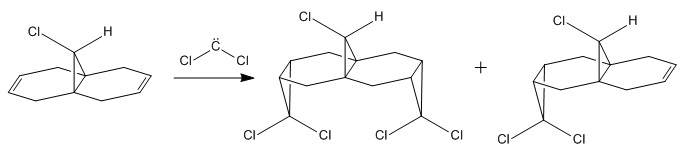

Orbital control of reactivity can be demonstrated in the reaction of molecule 12 (9-Chloro-1,4,5,8-tetrahydro-4a,8a-methanonaphthalene) with an electrophilic reagent as shown in Fig. 8.

The dichlorocarbene electrophile adds either endo or syn to the chloro substitutent and the mechanism shows the formation of a di-adduct (left) and a mono-adduct (right) in the ratio of 23:72 respectively[4]. Experimentally, the di-adduct is not observed. The regiospecific results of the reaction can be understood by considering the orbitals used within the reaction.The orbital of particular interest is the HOMO as it is presumed to be the most reactive towards electrophilic attack. Other orbitals that were looked at were the LUMO, LUMO+1, LUMO+2 and HOMO-1.

The energy of was optimised using the MM2 force field and the minimum energy was found to be 17.91 kcal/mol. The MOPAC/PM6 method was then used to provide an approximate representation of the valence-electron molecular wavefunction. However, inspection of these orbitals indicated some discrepancies in that the molecular orbitals should be symmetric about the plane of symmetry bisecting the molecule.It was observed that this was not the case resulting from a bug[5] present in the ChemBio 3D program. Various other methods were used to try and resolve the problem with some failing to yield any results. The results obtained below were obtained using the MOPAC/RM1 method.

|

|

|

|

|

The aforementioned reaction is an electrophilic reaction and as such will occur at the most electron rich alkene. Looking at the HOMO it can be seen that the greatest electron density is concentrated about the syn alkene as opposed to the anti alkene relative to the chlorine, accounting for the experimental observation. The endo alkene is made more nucleophilic as a result of the stabilising antiperiplanar interactions between the Cl-C σ* orbital and the occupied exo π orbital[4]. The lack of steric bulk within the molecule suggests both alkenes are equally likely to react so the MO theory used is sufficient to explain the reactivity of the molecule.

Vibrational Frequencies

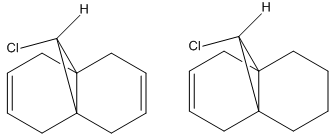

The aim of this section was to calculate and determine the influence of the C-Cl bond on the vibrational frequencies of the molecule. This was carried out by comparing the two compounds shown in Fig. 10 below:

The calculation was carried out by initially optimising the energy of both molecules using the MM2 methods followed by a second optimisation using the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian method. Molecule 12 has Cs symmetry, as previously mentioned, which improves the speed of calculation as only half of the molecule needs to be accounted for. The asymmetry of the dihydro derivative means this method cannot be used and so the calculation will take longer.

| Molecule | Syn C=C Stretch/cm-1 | Anti C=C Stretch/cm-1 | C-Cl Stretch/cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1757.03 | 1737.03 | 770.86 |

| Mono-hydorgenated Derivative | 1758.08 | - | 774.95 |

The data obtained for the C-Cl stretching frequency corresponds well to the literature value (600-800 cm-1)[6] however that obtained for the C=C stretching is significantly higher, for both the syn and anti alkenes, than the literature value of 1620-1680 cm-1[6].

Comparing the stretching frequencies of the syn and anti-alkenes shows the syn-alkene to have a higher frequency which indicates a higher bond energy making it less reactive. This contrasts the findings from the molecular orbital investigation and could be attributed to the fact that the strength of the C=C bond considers both the σ and π bonds whereas the electrophilic addition only accounts for the π bond. To be consistent with the experimentally observed result, bond energy must not significantly determine the reactivity and the π orbitals found in the syn-alkene must be better electron donors compared to those in the anti-alkene.

The difference between the stretching frequencies between the syn C=C bond in molecule 12 and its mono-hydrogenated derivative is insignificant. This could mean that the anti-alkene does not affect the strength of the syn-alkene in molecule 12.

Finally, comparison of the C-Cl stretch in molecule 12 and its derivative shows a difference of 4.09 cm-1 indicating that the C-Cl bond is stronger in the monoalkene compared to the dialkene. This can be attributed to the loss of orbital interactions on hydrogenation of the double bond, namely donation of electron density into the antibonding C-Cl orbital.

Further Investigation

A further investigation was carried out into substituents on the anti-alkene. Four different substituents; SiH3, OH, CN and BH2 were varied to investigate the effects of different electronic properties on the stretching frequency of both the anti and syn-alkene bonds along with the C-Cl stretching frequency. Table 5 and Fig. 11 below show the MM2 optimised geometry along with the stretching frequencies for the various substituents.

| Substituent | MM2 Energy/kcal mol -1 | Syn C=C Stretch/cm-1 | Anti C=C Stretch/cm-1 | C-Cl Stretch/cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiH3 | 17.62 | 1756.23 | 1690.33 | 763.75 |

| BH2 | 15.79 | 1756.55 | 1657.25 | 759.02 |

| CN | 16.72 | 1756.54 | 1706.30 | 765.76 |

| OH | 17.84 | 1756.18 | 1776.58 | 766.85 |

The data indicates that changing the substituent present on the anti-alkene has no impact on the stretching frequency of the syn-alkene. However, as expected, the change in substituent does impact the stretching frequency of the anti-alkene as well as that of the carbon-chloride bond.

Comparison of the unsubstituted diene with the anti-alkene containing either an SiH3, BH2 or CN substituent shows a decrease in vibrational stretching for both the C=C and C-Cl. This indicates a decrease in the energy of both of these bonds and can be accounted for by considering the atoms. In the case of CN the electronegative nitrogen means electron density will be removed from the alkene resulting in the decrease of vibrational frequency and therefore energy. SiH3 and BH2 are electropositive groups so will add electron density to the double bond, increasing the energy and therefore the vibrational frequency relative to the unsubstituted diene. However, this is not observed in the computed results and indicates in some way that both groups reduce the electron density of the alkene in some way.

On addition of a hydroxyl group to the anti-alkene, an increase in vibrational energy is observed for the C=C bond. This is not the case for the carbon chloride bond and a decrease is observed. This can be explained by considering the electronic properties of the hydroxyl group. This particular group can withdraw electrons inductively but can also donate electrons through resonance effects which results in the weakening of the C=C bond. As a result, the syn-alkene can donate electron density into the antibonding σ orbital of the C-Cl bond which reduces the energy of the bond relative to the unsubstituted diene.

Mini Project

This project involves the use of computational methods in the identification of two isomers resulting from a single reaction. Most organic reactions carried out give rise to a mixture of isomers which can be isolated and separated. It is important to know which isomer is formed to prevent catastrophic occurrences, for example, the morning sickness drug thalidomide. The medication was given to pregnant women to prevent morning sickness, however the chiral isomers had not been separated and one isomer resulted in abnormalities in the children, including cancer. Computational methods can be used to understand the mechanism of the reaction and can therefore help to determine which isomer will predominate.

This project looks into the the unusual regioselectivity of the dipolar cycloaddition reactions of nitrile oxides and tertiary cinnamides and crotonamides as proposed by Weidner-Wells et al.[7]. In particular, the focus is on the reaction between molecule A and the dipolarophile B as detailed in Fig. 12 below:

| Stretch | 1.64 | 1.57 |

| Bend | 10.31 | 9.76 |

| Stretch-bend | 0.46 | 0.39 |

| Torsion | -6.33 | -7.01 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | -2.94 | -4.96 |

| 1,4 VDW | 20.94 | 20.93 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -1.09 | -1.75 |

| Total Energy | 23.00 | 18.92 |

Both isomers were drawn in ChemBio3D and the MM2 force field was used to determine the minimum energy. The results of this simulation can be seen in Table 6. This shows molecule C to have a higher energy compared to molecule D which could be attributed to the unfavourable interaction between the benzene ring and the ethyl groups. Molecule D avoids this interaction by orientating the ethyl groups away from the benzene ring. This minimum energy fits with that observed in literature which states molecule D to be the predominate isomer, with a three times greater production rate[7]. This could also indicate that molecule D is the thermodynamic product, but as discussed in Section 1.1.1 above it is not possible to definitely confirm this without further consideration of the reaction conditions or transition states involved.

Looking at the contributing forces, it can be seen that no one force has a significantly higher impact on the destabilisation of molecule C relative to molecule D.

A further optimisation was then carried out. A Gaussian input file was created for each isomer using the DFT mpw1pw91 method with a 6-31G(d,p) basis set. These files were then scanned to obtain the optimised geometry. The output file obtained from the optimisation could be edited to compute various experimental techniques including IR and NMR.

The literature contains various physical and spectroscopic data with regards to molecule C and D namely; melting point, 1H NMR, 13 NMR, IR and mass spectometry. For this investigation, the 13 NMR and IR were computationally computed and compared to that found in literature.

NMR

The 13C NMR was provided in the literature so the starting point for the investigation was to computationally recreate the NMR for both isomers and compare to that determined by Weidner-Wells et al.[7] This was carried out by editing the output file obtained from the optimization and setting this to scan again. Literature reported that the NMR was carried out in chloroform so the reference for the computed NMR was also set to chloroform. Table 7 shows the experimental results along with the literature results and the difference observed between the two. The carbon number refers to the carbon atoms as labelled in Fig. 13.

| 13C NMR Chemical Shift for Molecule C | 13C NMR Chemical Shift for Molecule D | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Number | Calculated Shift/ppm | Reported Shift/ppm[7] | Difference/ppm | Calculated Shift/ppm | Reported Shift/ppm[7] | Difference/ppm |

| 1 | 139.3 | 138.6 | 0.7 | 136.1 | 138.2 | -2.1 |

| 2 | 125.9 | 129.1 | -3.2 | 122.8 | 129.3 | -6.5 |

| 3 | 126.2 | 129.0 | -2.8 | 123.9 | 128.7 | -4.8 |

| 4 | 125.2 | 128.9 | -3.7 | 122.3 | 126.6 | -4.3 |

| 5 | 124.3 | 129.0 | -4.7 | 121.8 | 128.7 | -6.9 |

| 6 | 125.8 | 129.1 | -3.3 | 123.3 | 129.3 | -6 |

| 7 | 153.1 | 154.8 | -1.7 | 154.4 | 158.1 | -3.7 |

| 8 | 67.8 | 59.9 | 7.9 | 54.9 | 55.7 | -0.8 |

| 9 | 85.2 | 89.0 | -3.8 | 86.5 | 87.3 | -0.8 |

| 10 | 139.3 | 135.9 | 3.4 | 128.6 | 135.8 | -7.2 |

| 11 | 121.0 | 126.2 | -5.2 | 121.1 | 127.8 | -6.7 |

| 12 | 125.5 | 127.5 | -2 | 122.4 | 128.6 | -6.2 |

| 13 | 123.8 | 127.8 | -4 | 122.0 | 127.9 | -5.9 |

| 14 | 124.5 | 127.5 | -3 | 122.6 | 128.6 | -6 |

| 15 | 120.0 | 126.2 | -6.2 | 124.7 | 127.8 | -3.1 |

| 16 | 162.2 | 167.7 | -5.5 | 156.4 | 166.2 | -9.8 |

| 17 | 44.9 | 40.9 | 4 | 39.2 | 41.9 | -2.7 |

| 18 | 16.2 | 14.5 | 1.7 | 10.2 | 12.5 | -2.3 |

| 19 | 46.6 | 42.3 | 4.3 | 39.2 | 40.6 | -1.4 |

| 20 | 14.7 | 12.6 | 2.1 | 13.4 | 14.2 | -0.8 |

The NMR was computed for both isomers and compared to the literature data to see which was the better fit. If the difference is significant enough, it is possible to determine the major product of the reaction. The magnitude of the total difference between the computed and reported chemical shifts were calculated and the average was taken. This yielded 6.1 ppm for molecule C compared to 7.33 ppm for molecule D, however this is not a totally accurate method. The ratio of formation of molecule c:molecule d was reported to be 23:77[7] which does not comply with the average differences calculated. This could be due to limitations and inaccuracies found in the computational calculations. Unfortunately this problem is not easily avoided but overall, the computed and literature results show a good correlation.

It was also noticed that the computational method yielded more peaks compared to those provided in literature. This results from the two phenyl rings present in each of the molecules. In an actual NMR, the molecules are free to move and rotate so equivalent sets of atoms will be accounted for by one peak at a specific chemical shift. However, in the computational method, the molecule is 'frozen' making the phenyl atoms inequivalent. To account for this, suspected equivalent atoms were compared to the same literature value and the difference calculated from there.

|

|

Optical Rotation

Optical rotation is a technique used to differentiate between chiral isomers of a particular molecule. Each of the product molecules being considered contains two chiral centres, emphasised with an asterisk in Fig. 14. This means four isomeric products are possible for each of the regioisomers and a total of eight product isomers can result.

The optical rotation technique can be used to distinguish between the many isomeric products possible. However, due to time constraints, this part of the investigation was not carried out. Optical rotation is particularly sensitive to the conformation of the molecule and, although both of the products contain rigid benzene rings, they also contain flexible bonds and ethyl groups. This would mean, for the test to be carried out accurately, both molecules would need to be further optimised to find the minimum energy conformation before the optical rotation could even be computed.

Conclusion

The 13C NMR technique used provided a good demonstration of how computational techniques can be used to confirm the findings of experimental investigations. The computed spectra for this particular experiment did not match with the ratio given in literature, but this can be attributed to limitations in the accuracy of the program.

If the investigation were to be furthered, the next step would be to look into the optical rotation of the eight chiral products mentioned above and see if one, or possibly more, of these were to predominate in the reaction. Infra red spectroscopy could also be used to further investigate the products of the reaction. If different peaks were to be present for each of the different isomers, this technique could help to determine which the major product is.

Conclusion

Overall, this investigation has provided an insight into the uses and limitations of various computational techniques along with a number of their uses.

References

- ↑ Junji Furukawa, Yoshiaki Kobuke, Takayuki Fueno, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1970, 92 (22), pp 6548–6553

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838 DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, pp 1891-1900

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2,, 1992, 447 DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ https://wiki.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php?title=Mod:organic

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 http://www2.ups.edu/faculty/hanson/Spectroscopy/IR/IRfrequencies.html

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 M.A. Weidner-Wells, S.A. Fraga-Spano, I.J. Turchi, J. Org. Chem., 1998, 63, pp 6319-6328