Rep:Mod1:lcs11

Introduction

The use of computers to model organic structures and reactivity has become of great importance and is a commonly used tool by many chemists. Such modelling is highly useful as it can rationalise the outcome of a reaction and provide information on possible improvements and modifications.

Solving the Schrödinger wave equation for a molecule would yield information about the system to a high level of accuracy and answer all questions regarding the properties of such system, however such calculations are in practical due to the amount of computer time they take.

Firstly the Molecular Mechanics (MM) approach will be used; this involves studying molecular properties without using quantum mechanical models.

Instead it uses the summation of individual energy terms to determine the total energy. The energy terms that are summed are;

1. Sum of all diatomic bond stretches

2. Sum of triatomic bond angle deformations

3. Sum of tetra-atomic bond torsions

4. Sum of all the non bonding interactions (Van der Waals)

5. Sum of electrostatic attractions of individual bond dipoles.

The MM model can then minimise this total energy by varying the parameters that define each of the above energy contributions, for example bond length. Force Fields that will be used are MM2 and MMFF94.

Secondly a quantum mechanical method will be used and a semi empirical Moleculer Orbital theory will be used to calculate the electronic effects on reactivity. This done by generating the electronic wave functions using the MOPAC/PM6 methof in ChemBio3D.

Finally Density Functional Theroy will be used to calculate spectroscopic properties of two isomers reported in a literature article.

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerization

Cyclopentadiene exists as a dimer at room temperature it can be cracked into the monomer at elevated temperatures. The dimerization is a [4π + 2π] cycloaddition otherwise known as a Diels Alder reaction, the participation of 6 π electrons in the reaction indicates that it proceeds via a Huckel transition state with both new bonds forming on the same side (suprafacially). The reaction is stereospecific and two possible products are possible depending on the orientation of the approaching monomers. The two possible isomers along with the mechanism and indicating the transition state for each are shown in Fig.1.

The energies of both isomers were minimised using the MM2 force field in ChemBio3D. The results of these molecular mechanics calculations are shown in table 1. The energy difference between them is 2.13kcal/mol with the Exo product being the one lower in energy and hence the expected thermodynamic product.However Alder et al [1] showed that the major product is the Endo isomer.

| Interaction | Exo | Endo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch / K cal Mol-1 | 1.28 | 1.24 | |

| Bend / K cal Mol-1 | 20.57 | 20.86 | |

| Torsion / K cal Mol-1 | 7.66 | 9.50 | |

| 1,4-VDV / K cal Mol-1 | 4.24 | 4.30 | |

| Total Energy / K cal Mol-1 | 31.88 | 34.01 |

The Endo rule can be used to rationalise this unexpected outcome i.e by consideration of the transition state energies opposed to the product energies. The endo rule states that the most stable transition state is the one with maximum overlap of the frontier molecular orbitals of the diene and the dienophile. In the transition state for the Endo product there are additional bonding interactions at the back of the diene stabilising the transition state and hence lowering its energy. In the exo product the frontier orbitals are not aligned to allow this extra bonding interaction and the transition state is not stabilised. This is shown in Fig.2. Therefore the kinetic product of the dimerization is the Endo isomer and the reaction is under kinetic control.

Hydrogenation

| Interaction | Molecule 3 | Molecule 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch / K cal Mol-1 | 1.23 | 1.10 | |

| Bend / K cal Mol-1 | 18.96 | 14.52 | |

| Torsion / K cal Mol-1 | 12.15 | 12.51 | |

| 1,4-VDV / K cal Mol-1 | 5.73 | 4.50 | |

| Dipole-Dipole / K cal Mol-1 | 0.16 | 0.14 | |

| Total Energy / K cal Mol-1 | 35.93 | 31.18 |

The cyclopentadiene dimer can be hydrogenated at either of the double bonds to give the dihydro derivative then after prolonged reaction times the tetrahydro derivative is formed. Molecules three and four show the two dihydro products, and their energies were minimised with MM2 force field, the results are shown in the table. Molecule 4 was found to have a lower energy by 4.76 kcal/mol hence hydrogenating the cyclohexene double bond stabilises the molecule more than hydrogenating the double bond in the 5 membered ring. Therefore molecule 4 is the expected thermodynamic product. This can also be concluded by comparing the energies of 3 and 4 to that of the endo isomer from which they originated, the energy of this was 34.01 kcal/mol, the energy of molecule 3 is higher than this indicating it is unfavourable to form and the energy of molecule 4 is lower indicating it is favourable to form. The contribution to the total energy that shows the biggest difference is the bend energy the can be rationalised by considering the position of the double bond that is hydrogenated in both molecules, the double bond in molecule 3 is part of a norborene unit meaning it is more strained, this is evident in the sp2 bond angles which are 107o and 127o indicating strain in the double bond. This is compared to the bond angles of 124o and 122o in molecule 3 which are much closer to the ideal double bond bond angles, hence hydrogenated the norborene double bond relieves more strain from the molecule. therefore it can be concluded that molcule 4 is the major product due to the larger release of strain on removed the double bond from the norborene unit.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

Reaction of Pyridinium Ring in N-methyl Pyridoxazepinone (molecule 5) with Grignard Reagent

The optically active derivative of prolinol (molecule 5) reacts with methyl magnesium iodide to alkylate the pyridine ring in the 4-position. The absolute stereochemistry of the product and the mechanism is shown in Fig.4. The high regio and stereoselectivity of the product can be credited to chelation of the Mg to the oxygen atom of the carbonyl[2] hence the delivery of the Me to specifically the C4 atom and the driving force being the release of the positively charged nitrogen atom. The reactant (molecule 5) was drawn in ChemBio3D and its energy minimised using the MMFF94 force field, the conformation of the molecule was then varied by moving atoms around and the energy was minimised for each conformation for example varying the conformation of the benzene ring from chair to boat. The dihedral angle between the carbonyl oxygen and the carbon atom in the benzyl ring that is alkylated was noted along with the minimised energy of each conformation. The results are shown in the table below.

| Energy kcal/mol | Dihedral Angle/ o | |

|---|---|---|

| 58.99 | 25.22 | |

| 57.61 | 22.23 | |

| 57.45 | 15.43 | |

| 57.42 | 7.44 | |

| 57.41 | 4.13 |

Clearly different energies correspond to changes in the dihedral angles, the important point is that all the dihedral angles are positive meaning that the carbonyl oxygen is always above the plane of the benzyl ring. Hence the methyl group will always be delivered above the plane of the ring as the lone pair on oxygen coordinates to the electron deficient Mg atom. It is also important to consider steric effects as the methyl group bonds to the molecule on the same side as the carbonyl there will be some additional steric clash however the methyl group is only small and the coordinative interaction overrides additional steric clashes giving the stereochemistry observed. The same calculations were attempted including the Mg atom in the structure, however ChemBio3D gave an error message that didn't allow the calculations to be run. This is because for the program to minimise the energy it must know certain parameters for each bond for example the bond length and the force constants. These values are not known for the Mg atom and the energy could not be minimised.Further more the bond between Mg and Oxygen is not fully formed and ChemBio 3D cannot deal with such coordinative interactions.

Reaction of Pydridinium Ring in N-methyl Quinolinium Salt (molecule 7) with Aniline

A similar reaction was investigated as shown in Fig.7, here the nucleophile is aniline and is reacting with the pyridium ring in molecule 7. Again the stereochemistry of the product can be explained by finding the lowest energy conformation of the reactant. The molecule was drawn and the energy minimised, then as before changes were made to the conformation to try and find a lower energy conformation. The dihedral angle between the carbonyl oxygen and the carbon which is attacked by the nucleophile were noted as it is thought that due to the larger nucleophile and the lack of coordinating interaction between the nucleophile and the reactant, that the nucleophile will attack on the opposite side of the benzyl ring to the carbonyl group. The results are shown in the table below.

| Energy kcal/mol | Dihedral Angle/ o | |

|---|---|---|

| 101.813 | 33.65 | |

| 113.21 | 37.42 | |

| 99.67 | -35.27 | |

| 99.53 | -38.84 |

Firstly the dihedral angle was found to be positive which would not explain the stereochemistry of the product, therefore attempts were made to find a lower energy conformation with the carbonyl group on the opposite side of the ring. It was also found in the first minimised conformation that the benzyl ring attached to the 7 membered ring was above the plane of the molecule, like the carbonyl group. Therefore lower energy conformations were found when this benzyl group and the carbonyl group were dragged to the other side of the ring and then the structure was minimised. In the above table the conformer with the highest energy (113.21 kcal/mol) was found when the benzyl was in the same plane as the molecule and then the energy became lower when it was moved to the other side. Clearly the energy differences aren't huge, but the fact that the energy is lower when the dihedral angle is negative is crucial in explaining the stereochemistry of the product. Therefore the stereochemistry of the product is due to the steric control from the carbonyl group directing the larger nucleophile onto the opposite face and hindering attack on the same face.

The ideal improvement to these calculations would be to include electronic effects and not base the calculations on known quantities such as bond lengths and force constants which is what molecular mechanics does. Instead MOPAC/PM6 methods could be used which include molecular orbitals and electronic effects to find more accurate results.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

Atropisomers are stereoisomers that result when rotation about a single bond is restricted due to high steric demand hindering free rotation. Fig.6 shows an example of such isomers, molecule 9 or 10 is key intermediate in the synthesis of Taxol.

Molecule 9 was drawn and minimised with the MM2 force field giving an energy of 54.37 kcal/mol. Lower energy conformations were then attempted to be found by moving atoms of the cyclohexane ring into known stable conformations, firstly the atoms were moved into the chair conformation and the energy minimised yielding a result of 48.90 kcal/mol. So the energy was lowered by 5.47 kcal/mol a similar results was obtained when using the MMFF2 force field where a energy difference of 5.77 kcal/mol was calculated. More stable conformations of the cyclohexane ring were attempted such as the boat or twist boat but on energy minimisation they reverted back to the chair conformation. Finally other changes were made to the molecule by moving the atoms around but a lower energy could not be found. The same process was carried out on molecule 10 with the initial energy being 48.90 kcal/mol and then after rearrangement the lowest energy conformation that could be found was again by putting the cyclochexane ring into the chair conformation, the energy was then 43.16 kcal/mol. The tabulated energies and most stable conformations are shown below.

| Molecule 9 | Molecule 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy before rearrangement/ kcal mol-1 | 54.37 | 48.90 | |

| Energy after rearrangement/ kcal mol-1 | 48.90 | 43.16 | |

| Energy Difference / kcal mol-1 | 5.47 | 5.74 |

| Molecule 9 | Molecule 10 | ||||||

|

|

On analysis of the different energy contributions to the total energies it was apparent that the largest difference came from the bend contributions indicating that it is the angles around the sp2 carbon effecting the overall energy. Therefore the angles around this carbon were measured for each of the isomers, this yielded the following results.

| Molecule 9 | Molecule 10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bend energy/ kcal mol-1 | 15.83 | 9.89 | |

| Angle 1/ o | 115.2 | 120.5 | |

| Angle 2/ o | 126.3 | 120.5 | |

| Angle 3/ o | 118.1 | 118.5 |

Now it is much clearer why molecule 10 exists with a lower energy. The ideal bond angles around a sp2 carbon is 120o and in molecule 9 the bond angles deviate significantly from this value hence causes an increase in the bending energy, where as in molecule 10 all the angles are 120o or very close to. It is also expected that there is some steric clash between the carbonyl when it is pointing up with the bridging isopropyl group, this steric clash is not present in the down isomer hence resulting in a lower energy. Therefore it can be concluded that molecule 10 is thermodynamically more stable one and on standing molecule 9 will isomerise to molecule 10, this is consistent to what is found in literature[3].

Due to the position of the alkene in molecules 9 and 10 it might be thought that the alkene would be reactive as it is known that alkenes at bridgehead carbons are particularly strained. However it has been noted that on subsequent functionalisation of the alkene, it reacted very slowly. This was attempted to be rationalised by replacing the double bond with a single bond and hence hydrogenating the alkene, calculations were then run on this new model to minimise the energy. The lowest energy conformation that could be found for the hydrogenated molecule 9 was 69.9 kcal/mol and for molecule 10 64.6 kcal/mol both significantly higher than reactants containing the double bonds. Hence why the isomers were found to react slower. This slowness can be credited to size of the ring in which the alkene functionality sits. Due to the large ring the alkene can be considered as hyperstable[4] which means that the strain in the alkene is less than the parent saturated hydrocarbon this is due to the increased vicinal and transannular hydrogen interactions[5]. This occurs because one of the carbons of the alkene is a bridghead carbon hence twisting the alkene geometry and reducing the HOMO-LUMO gap, the HOMO and LUMO will become degenerate if the twisting generates a twist angle of 90o.

Modelling Using Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Previously a purely mechanic model has been used in calculations however it is important to consider the electronic effects on reactivity, more specifically the molecular orbitals of a moleculer. This is what semi-empirical Molecular orbital theory does. In this next exercise MOPAC PM6 MO method and Gaussian density functional theory are used to perform energy minimisations, calculate molecular orbitals and obtain infra red spectra.

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

Halton et al[6] showed that addition of dichlorocarbene to 9-chloromethanonaphthalene shows high regioselectivity producing 72% the syn trichloride. This is shown in Fig.10.

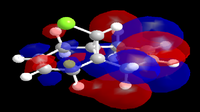

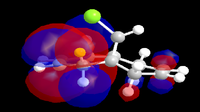

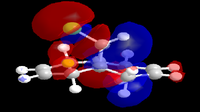

In an attempt to understand the observed reactivity MOPAC/PM6 methods were used to obtain an approximate representation of the valence-electron molecular orbitals. Particular attention was paid to the HOMO and to orbitals close in energy to the HOMO as it is these orbitals which usually control the reactivity of a molecule. These molecular orbitals are shown below.

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 |

|

|

|

|

|

The reaction in Fig.10 is an electrophilic addition therefore it is expected that it will occur at the most nucleophilic alkene. By examining the HOMO of the molecule it is clear that the electron density is highest around the syn alkene and low around the anti alkene (to the Cl atom). The high electron density at the syn alkene makes it more nucleophilic and hence more susceptible to electrophilic attack, this explains the observed reactivity. From the above the diagrams the HOMO has already been identified as the π orbital of the syn alkene, by further inspection the HOMO+1 can be identified as the anti π orbital. The relative energies of these two orbitals determines the reactivity of the molecule, as previously seen the higher energy orbital is the one attacked by the electrophile. Therefore whatever determines the relative energy's of these two orbitals will determine the regioselectivly of this reaction. Rzepa et al[7] attributed this to the stabilising antiperiplaner interaction between the C-Cl sigma star orbital and the occupied anti π orbital, i.e an interaction between what is shown above to be the HOMO-1 (anti π orbital) and the LUMO+2 (C-Cl σ* orbital) hence lowering the energy of the anti π orbital and leaving the syn π orbital at the same energy and therefore more nucleophilic. It is also possible to assign the LUMO and the LUMO+1 to the π* orbitals of the anti and syn double bonds respectively.

Vibrational frequencies

To study the effect of the C-Cl bond on the vibrational frequencies of the above syn diene (molecule 12), the stretching frequencies were calculated for the C-Cl and C=C bonds and compared with monohydrogenated molecule 12A. Both molecules are shown in Fig.11. The method used was B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) Gaussian geometry optimization and frequency calculation, the results of which are shown in the table below.

| Molecule | syn C=C stretch /cm-1 | anti C=C stretch /cm-1 | C-Cl stretch /cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1757.5 | 1737.1 | 770.8 |

| 12a | 1758.1 | - | 775.0 |

As previously explained there is a stabilising interaction between the anti double bond and the C-Cl σ* orbital and as electron density moves from the π orbital of the double bond into the σ* orbital of the C-Cl bond it follows that the π bond will become weaker and also the σ bond of the C-Cl will become weaker. A decrease in the vibrational frequency of a bond is indicative of a weakening of the bond and hence a reduction in bond order. Therefore as expected the vibrational frequency of the anti double bond is lower than that of the syn, confirming the presence of this stabilising interaction. Similarly when comparing the stretching frequency's of the C-Cl bonds in molecules 12 and 12a it can be seen that it is higher in the monohydrogenated product indicating a stronger bond when the interaction with the anti double bond is not present. Finally it can be seen that the frequency of the syn double bond in 12 and 12a does not really vary showing that there is no interaction affecting this double bond in either 12 or 12a that is not present in the other molecule. The diene has Cs symmetry however the change of the sp2 centres to sp3 breaks this symmetry and molecule 12ab has C1 symmetry.

For further investigation of the effect of the proposed interaction between the HOMO-1 and the LUMO+2 various substitutes were placed on the anti double bond that would vary the electronic properties of the double bond, and the effects are observed like before by comparing the stretching frequency's of the molecules. Three substituents were analysed OH, CN and SiH3 to yield molecules 12B, 12C and 12D shown in Fig.12.

| Molecule | syn C=C stretch /cm-1 | anti C=C stretch /cm-1 | C-Cl stretch /cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12B | 1757.8 | 1753 | 765.3 |

| 12C | 1756.5 | 1706.3 | 765.8 |

| 12D | 1756.2 | 1690 | 763.8 |

Firstly considering molecule 12B the OH group is inductively electron withdrawing but can donate a lone pair of electrons via resonance, therefore the increase in the anti C=C stretching frequency and a the decrease in the C-Cl stretching frequency can be explained as the OH group donates electron density into the alkene and increasing its strength and bond order hence increaing the frequency. Then because of this higher electron density, the alkene is more able to donate electron density in the C-Cl σ* orbital which in turn reduces the bond order and strength of the C-Cl bond compared to the unsubstituted diene (molecule 12). There is no change in the frequency of the syn C=C stretching frequency. Secondly considering molecule 12C with the CN substituent there is a large decrease in the stretching frequency of the anti double bond which is expected due to the electron withdrawing properties of CN which significantly reduces the electron density of the double bond. Finally the effect that the Silyl group has on molecule 12D is unexpected, the stretching frequency and hence the bond strength are greater reduced despite silicon being more electropositive than carbon. The lower freqeuncy suggests that the electron density in the double bond is greatly reduced indicating that in some way the silyl group reduces the electron density, it is possible this is due to silicon d orbitals accepting electron density from the double bond as SiH3 is a weak π acceptor. The C-Cl stretching frequency is also lower in 12D indicating donation into the C-Cl σ* orbital is also stronger.

Structure based Mini Project

This mini project will explore how the cyclization of 1-alkynylimidazoles containing nucleophilic groups at their 2 position result in two types of bicylic imidazoles depending on the regiochemistry of the cyclization. More specifically (2) shown below can undergo 6-endo-dig or 5-exo-dig cyclization to yield imidazo[1,2-c]-oxazoles and imidazo[2,1-c][1,4]oxazine heterocycles respectivley. Often the ring size of the products can be predicted by applying Baldwins[8] rules which are an empirically devised set of rules for ring closure based on stereolectronis effects, however both products here are allowed by these rules giving no explanation for the observed products. Which cyclization proceeds depends on the substituent on the alkyne group and the conditions and reagents used to promote the cyclization. The primary literature for this project is from the article by Laroche et al[9] in which control over the regioselectivity of the cyclization with choice of reagents is clearly demonstrated. It was found that under basic conditions the 5-exo-dig was the preferential product and under transition metal catalysis exclusively the 6-endo-dig product was produced. One such reaction from the article is shown below where Phenyl-(1-(2- phenylethynyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methanol (2) is cyclized under basic conditions to yield the 5-exo-dig product (Z)-5-Benzylidene-7- phenyl-5,7-dihydroimidazo[1,2-c]oxazole (3) or under the catalysis of AuCl3 to yield the 6-endo-dig product 6,8-Diphenyl-8Himidazo[ 2,1-c][1,4]oxazine (4)

Computational methods will be used to predict spectroscopic properties such as NMR and IR which can be used to distinguish between the two products and compared to literature. The GIAO method 13C NMR calculations are ran to show that it is possible to distinguish between the two products, the IR spectras will also be calculated. These calculation will be done using Density Functional Theroy (DFT) which is a quantum mechanical modelling method which allows the properties of many electron molecules to be determined using functionals of the electron density.

Firstly the 13 NMR was predicted. Both isomers were run in ChemBio 3D and their energy minimised using the MM2 force field, the lowest energy conformation of 3 that could be found had an energy of 28.4 kcal/mol however for 4 a lower energy of 25.08 kcal/mol was found. A Gaussian input file was then created for each isomer using the DFT mpw1pw91 method with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. The files were submitted to SCAN and the optimized geometry's obtained, the input files were then edited for calculations of the NMR spectra to be run. The solvent used was chloroform. The results of these NMR calculations are shown in the table below and the optimized geometries jmols of the isomers can be seen in the above introduction.

| Carbon Number | Chem.Shift(Comp)/ppm | Chem.Shift(Exp)/ppm | Diff. in comp and exp/ppm |

| 1 | 124.6 | 129.4 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 125.3 | 128.9 | 3.6 |

| 3 | 121.4 | 126.6 | 5.2 |

| 4 | 132.9 | 135.9 | 3.0 |

| 5 | 121.4 | 126.6 | 5.2 |

| 6 | 125.3 | 128.9 | 3.6 |

| 7 | 78.4 | 80.1 | 1.7 |

| 8 | 146.4 | 150.8 | 4.4 |

| 9 | 132.0 | 135.1 | 3.1 |

| 10 | 108.1 | 110.3 | 2.2 |

| 11 | 141.1 | 144.1 | 3.0 |

| 12 | 86.1 | 85.4 | -0.7 |

| 13 | 131.5 | 133.8 | 2.3 |

| 14 | 124.1 | 127.3 | 3.2 |

| 15 | 125.2 | 128.5 | 3.3 |

| 16 | 121.7 | 125.7 | 4.0 |

| 17 | 125.2 | 128.5 | 3.3 |

| 18 | 124.1 | 127.3 | 3.2 |

| Carbon Number | Chem.Shift(Comp)/ppm | Chem.Shift(Exp)/ppm | Diff. in comp and exp/ppm |

| 1 | 123.9 | 128.7 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 124.9 | 128.4 | 3.5 |

| 3 | 122.0 | 127.1 | 5.1 |

| 4 | 135.1 | 135.1 | 4.5 |

| 5 | 122.0 | 127.1 | 3.5 |

| 6 | 124.9 | 128.4 | 3.5 |

| 7 | 75.7 | 76.1 | 0.4 |

| 8 | 133.9 | 136.7 | 2.8 |

| 9 | 125.8 | 129.2 | 3.4 |

| 10 | 112.8 | 115.6 | 2.8 |

| 11 | 101.8 | 102.0 | 0.2 |

| 12 | 139.9 | 143.0 | 3.1 |

| 13 | 129.8 | 131.9 | 2.1 |

| 14 | 120.3 | 124.4 | 4.1 |

| 15 | 125.4 | 128.5 | 3.1 |

| 16 | 125.5 | 128.9 | 3.4 |

| 17 | 125.4 | 128.5 | 3.1 |

| 18 | 120.3 | 124.4 | 4.1 |

There are large differences in the NMR's of the two products. The chemical shifts of atoms 11 and 12 in both molecules are quite different allowing easy identification of the product just by observing these peaks. In the product 3 atom 12 lies outside the ring and is present as an acyclic alkene with a chemical shift of 86.1 ppm however in product 4 atom 12 is now one end of a cyclic alkene which is adjacent to the the oxygen atom, hence the nuclei is more deshielded and a downfield shift is observed resulting in a chemical shift of 139.9 ppm. The opposite shift is observed for atom 11 which in molecule 4 when moved away from the oxygen becomes more shielded and an upfield chemical shift is observed. Large differences in the chemical shifts of atoms 7, 8, 9 an 10 are also observed and would allow the product to be identified. The chemical shifts off all the aromatic carbons are very similar to other aromatic in the same molecule and to that of the carbon nuclei in the other molecule meaning that these chemical shifts could not be used to distinguish between the molecules. However they have been assigned and compared to literature above for completeness. On the calculated NMR spectra there were more peaks than given in literature, this is because when the NMR is calculated it is done so on a snapshot of the molecule at a particular time. The result of this is observing 2 peaks for 2 atoms which may actually be chemically equivalent on the NMR timescale. For example on the calculated spectra a peak was present for nuclei 5 and a a separate peak for nuclei 3, however the literature chemicals shifts stated one chemical shift for these two atoms. Therefore for an accurate comparison to be made the calculated chemical shifts of atoms 5 and 3 were averaged.

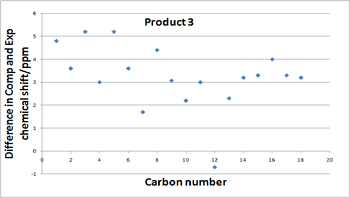

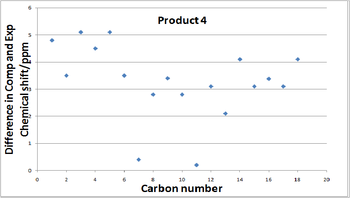

Now it has been established that differentiation of the two products is possible by comparing their NMR chemical shifts a comparison to the published literature values is important to see if the computational results calculated are agreement with what Laroche et al found. The final column of each table show the the difference between the experimental values and the calculated values and the graphs below show the deviation. Clearly their is some deviation which is expected as approximations have been used in the calculations resulting in a higher calculated chemical shift than literature states almost every time. Nevertheless the correlation is actually quite good with the difference rising above 5ppm only once. The root mean squared (RMS) devaition value is 3.50 ppm for molecule 3 and 3.54 ppm for molecule 4, both are low and similar in value indicating the NMR data obtained is reasonably accurate. The graphs below present a more visual way of observing the the differences in the chemical shifts to literature.

|

|

Now a similar process is carried out to calculate the vibrational frequencies of the two products to determine whether the IR spectras could be used to differentiate between the two products. Again a comparison to the frequencies given in the literature article will be carried out, however in the article the frequencies are just listed and not assigned making it difficult to assign there frequencies. As before a Gaussian input file was created using the b31yp/6-31G(d,p)method and edited to calculate the frequencies. The formatted gaussian checkpoint file was then opened in Gaussview and the vibrational modes could be animated and observed, this also calculated the intensities of each frequencies. Only the frequencies with high intensities have been included in the results and many of the C-H and C-C frequencies have been omitted as they reveal nothing about the product.

| Calc.Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Assignment | Exp. Frequency cm-1 |

| 3205, 3207 | 32.4, 23.1 | C-H stretch | 3126 |

| 1751 | 429.2 | C=C (between atoms 11 and 12 | 1704 |

| 1658 | 35.1 | C=C aromatic stretch | - |

| 1600, 1454 | 102.5, 54.2 | C=N | - |

| 1512 | 70.9 | C=C (between atoms 9 and 10) | 1536 |

| 1321 | 70.0 | C-H wag | - |

| 1049, 1015 | 110.4, 51.8 | C-O stretch | 1030, 996 |

| Calc.Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Assignment | Exp. Frequency cm-1 |

| 3207, 3200 | 20.9, 27.0 | C-H stretch | 3112 |

| 1710 | 28.7 | C=C (between atoms 11 and 12 | 1652 |

| 1579, 1473 | 16.1, 59.3 | C=N | 1484, 1449 |

| 1529 | 128.4 | C=C (between atoms 9 and 10) | - |

| 1338 | 68.5 | C-H wag | - |

| 1089 | 91.9 | C-O stretch | 1162 |

| 746, 756 | 43.0, 62.7 | ring breathing | 749 |

On looking at IR data obtained the difference in the two spectra is not quite as obvious as it was for the NMR's. However some differences are present allowing identification of the two products, firstly the stretching frequency of the double bond between atoms 11 and 12 is different by 41 cm-1 with this stretch occurring at 1751 cm-1 for the exocyclic double bond in product 3 and the lower value of 1710 cm-1 for the endo cyclic double bond in product 4. This lower frequency is typical of cyclic double bonds which are usually difficult to observe in IR spectra due to a low dipole moment and low intensity. This is true here as the intensity of the double bond in product 4 is much less intense than in 3 meaning that on a real IR spectra it would be much harder to identify. When comparing these frequencies to those given in the article, there is a similar difference of 52 cm-1 however the actual values are about 50cm-1 lower than the calculated values which is expected as it is known that errors in the predicted wavenumbers are systematically too high for stretches and are usually out by about 8%, here however the error is much smaller and the calculated values are systematically to high for stretches by about 3%. These errors are because the calculations are run for the molecule in the gas phase which is not the case in the literature article. None of the wavenumbers are identical to the other molecule however the differences are sometimes subtle and high resolution spectra may be needed to observed them, however the differences are sufficient for the IR spectra to be used to identify the products. And again the assignments made by the calculations are in agreement with the literature article.

This vibrational analysis will also result in an entropy correction to the energy which will yield in effect a ΔG for each molecule. These energies are shown in the table below.

| molecule | ΔG/ Hartrees | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | -878.8332 | |

| 4 | -878.8348 |

These energies correspond to a difference of 0.931 kcal/mol with product three being very slightly lower in energy. This small energy difference fits with the experimental observations that the regioselectivity could be almost completely controlled by choice of reagent indicating that the difference in energy of the two products has little effect on the outcome.

Mechanistic explanation of formed isomers

Now it has be established that is possible to distinguish between the two products by spectroscopy the reasons as to why each product is formed under the different conditions will be considered.

Hiroya[10] et al reported an investigation into what effects the regiochemical control over 5-exo-dig cyclization vs. 6-endo-dig cyclization under basic conditions. They concluded that that the terminal substituent on the alkyne played an important role. When this substituent was hydrogen or an aromatic ring the 5-exo-dig product always dominated however when smaller alkyl groups were present a mixture of the 5 membered and 6 membered products were observed and only when a very bulky alkyl group was present was the 6-endo-dig product observed exclusively. They suggested that the cause of the observed regioselectivity was not the electronic nature of the substituent on the triple bond but by its steric bulkiness. When a large alkyl group is present there is a large amount of steric repulsion in the transition state resulting in the 6-endo-dig product. Therefore the article by Laroche reporting the 5-exo-dig product under basic conditions is in agreement with this research as the substituent on the triple bond on this reaction is an aromatic ring meaning there will be little steric repulsion in the transition state and the the 6-endo-dig product is not favoured. Furthermore it has been suggested by Laroche[9] et al that under basic conditions it is expected that competition would occur between the 5-exo-dig product and the 6-endo-dig product, however in the substrate the nitrogen atom attached to the triple bound will be strongly destabilised if a carbonic species is generated alpha to this nitrogen, and this would be the case if the 6-endo-dig cyclization was to occur. This destabilisation is expected to be less if the carbonic species is generated beta to the nitrogen and outside the ring where the aromatic group would have a stabilising effect hence favouring the 5-exo-dig cyclization product under basic conditions. It is thought that the cycloisomerizations under π-acid metal conditions is a distinct case resulting in exclusively the 6-endo-dig cyclization due to the mechanism of the catalysis. The proposed mechansim starts with activation of the alkyne by forming a [η2-(alkyne)- AuCl3] complex and coordination like this results in the rate of 6-endo-dig cyclization being much faster due to the small distance between the nucleophilic oxygen and the terminal carbon of the alkyne in this activated complex. This [η2-(alkyne)-AuCl3] was proposed by Behrens[11].

Further Investigation

As previously discussed Laroche's article states that the 5-exo-dig cyclization product is observed under basic conditions, however no mention is made to the stereochemistry of the double bond in this molecule. It is stated that the Z isomer is the product and it is this stereochemsity that all the above calculations have been run on. In attempt to verify it is in fact the Z isomer that is produced the same calculations was carried out on the E isomer of product 3 (E isomer =3a) to see if spectroscopically a difference could be observed. This E isomer is shown below along with a jmol of its optimized structure.

From the initial energy minimisation using the MM2 force field the energy was found to be 37.5 kcal/mol which is significantly higher than the initial energy values obtained for isomers 3 and 4. Presented below is the results of the NMR and IR calculations that were run.

Firstly the NMR data will be analysed. Very little difference is observed in the NMR's of molecule 3 and 3a, similar differences to literature are observed and RMS deviation is 3.30 ppm, this is slightly less than for 3 indicating that the chemical shifts for 3a fit the experimental data better. However this difference is small and on closer inspection not all shifts show a better correlation, some show worse. This is expected as 13C NMR is not typically used to tell apart the steriochemistry of alkenes as their chemical shifts do not show much difference. The only chemical shift that may be considered to give some indication of the steriochemistry is that of nuclei 13, in the Z isomer this nuclei is closer to the lactone oxygen atom so will be more deshielded and hence resonate further downfield than this nuclei is the E isomer. This is in fact observed in the calculated values with the chemical shift of 131.5 ppm in the Z isomer and 131.2 ppm in the E isomer, comparing these to the experimental value of 133.8ppm indicates that in the article it is the Z isomer being formed. However again these differences are very small and may just be down to the approximations used in the calculations.

A Similar conclusion can be drawn for the vibrational data, there is little difference in the spectra making it difficult to differentiate between the two using the IR spectra. The most prominent difference is the increase in frequency of the C-O stretching vibration which shifts from 1049 cm-1 in the Z isomer to 1132cm-1 in the E isomer and again the calculated value for the Z isomer is closer to the recorded experimental value. The free energy of 3a was calculated to be -878.828 Hartrees. This was converted to kcal/mol and found to be 3.18 kcal/mol lower in energy that the Z isomer. Indicating that 3a is the preferred product contrary to the previous evidence.

| Carbon No. | Chem.Shift(Comp)/ppm | Chem.Shift(Exp)/ppm | Diff. in comp and exp/ppm |

| 1 | 124.6 | 129.4 | 4.8 |

| 2 | 125.1 | 128.9 | 3.8 |

| 3 | 121.8 | 126.6 | 4.8 |

| 4 | 133.3 | 135.9 | 2.6 |

| 5 | 121.8 | 126.6 | 4.8 |

| 6 | 125.1 | 128.9 | 3.8 |

| 7 | 75.8 | 80.1 | 4.3 |

| 8 | 148.5 | 150.8 | 2.3 |

| 9 | 130.9 | 135.1 | 4.2 |

| 10 | 111.1 | 110.3 | -0.8 |

| 11 | 141.4 | 144.1 | 2.7 |

| 12 | 86.1 | 85.4 | -0.7 |

| 13 | 131.2 | 133.8 | 2.6 |

| 14 | 125.4 | 127.3 | 1.9 |

| 15 | 125.3 | 128.5 | 3.2 |

| 16 | 123.4 | 125.7 | 2.3 |

| 17 | 125.3 | 128.5 | 3.2 |

| 18 | 124.9 | 127.3 | 2.4 |

| Calc.Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Assignment | Exp. Frequency cm-1 |

| 3208, 3199 | 26.4, 31.4 | C-H stretch | 3126 |

| 1752 | 448.7 | C=C (between atoms 11 and 12 | 1704 |

| 1657 | 32.0 | C=C aromatic stretch | - |

| 1607, 1455 | 72.9, 37.6 | C=N | - |

| 1515 | 23.1 | C=C (between atoms 9 and 10) | 1536 |

| 1329 | 48.4 | C-H wag | - |

| 1132, 1020 | 168.6, 45.9 | C-O stretch | 1030, 996 |

The usual method to distinguish between E and Z isomers would be to measure the vicinal hydrogen coupling, however this is not possible here due to cyclic carbon not having hydrogen atoms. Proton NMR would though be very useful in deciding if the product was E or Z. The techniques used to calculate the 13C spectra could be used but the results are much less reliable in proton NMR therefore unlikely to provide any useful evidence. However the differences that would be expected can be considered. The key difference that would be expected in the NMR of the two isomers would be the chemical shift of the protons on carbon atoms 12 and 14. In molecule 3 the hydrogen atom at carbon 12 is trans to the lactone oxygen where as in molecule 3a it is cis to the lactone oxygen and it is likely that in the cis conformation the proton will be more deshielded due to the oxygen and appear further downfield. A similar situation arises for the aromatic hydrogen on carbon 14, in molecule 3 it sits closer to the lactone oxygen so is expected to experience a downfield shift compared to the same proton in 3a. However with the available computational techniques reliable 1H NMR calculations and these suggestions can not be tested. Praveen[12] et al found that the Z isomer ( for a similar set of molecules) was the thermodynamically most stable and on initial reaction a mixture of the two isomers was found which when left to stand for 6 hours resulted in only the Z isomer. They also give chemical shifts of the vinylic protons for both the Z and E isomer, 5.95 ppm and 6.49 ppm respectively, as mentioned before this proton is more deshielded in the E isomer due to its proximity to the the lactone oxygen. The chemical shift given for this proton by Laroche is 5.5 ppm which strongly indicates the presence of the Z isomer. Despite what is mentioned above about the 1H NMR calculations being much less reliable they were analysed anyway to see if the expected trend explained above was observed. The aromatic protons and the protons on the imidazole ring all have very similar chemical shifts with many of them overlapping making this region of the spectra hard to assign, since little difference is expected for this protons they are not included in the results. The vinylic proton and the the proton on carbon 7 (adjacent to the lactone oxygen) however appear further upfield and their values are shown below along with what Laroche reported.

| 3 (Z) /ppm | 3a (E)/ppm | Exp/ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vinylic proton | 5.7 | 6.0 | 5.5 |

| Proton on C-7 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

As expected the vinylic proton in 3a appears further downfield and and the lower chemical shift calculated for 3 corresponds better to the experimental data reported providing the first piece of evidence that the isomer in the article is on fact the Z isomer as reported.

In order for the stereochemistry of the double bond to be firmly assigned 1D NOE spectroscopy would need to be employed. Unfortunately Laroche[9] did not report such data but however, Praveen[12] did for a similar set of molecules. If the molecule was in the Z conformation selective irradiation of the vinylic proton would effect the enhancement of the hydrogen atoms within approximately 5 angstroms and if the product was in the E conformation the protons signals that are enhanced are different hence each isomer can be identified.

The calculations attempting to distinguish between the E and Z isomers have been fairly inconclusive with only the usually unreliable 1H NMR calculations provided information allowing us to distinguish between the two.

Dykstra[13] et al reported that when the nucleophile approaches the triple bond with the ideal angle then the substituents on the either end of the triple bond will move trans to each other. Such trans movement in this case would result in the Z isomer. In order for a similar conclusion to be made here an analysis of the transition states would need to be done in order to observe the nucleophiles angle of approach in each case to determine the most favourable product.

Conclusion

This project has shown that computational techniques can be extremely useful in providing spectroscopic data of a molecule leading to easy identification of two possible products . NMR calculations which ran very quickly provided conclusive evidence in distinguishing between isomers 3 and 4 and the results found to be in good agreement with literature. Determining the stereochemistry of the double bond in the 5-endo-dig cyclization product was less conclusive based on the computational techniques employed. However comparison with other literature articles suggested that the assignment of the product as the Z isomer was correct. Ideally further techniques such a X-ray crystallography or 1D NOE spectrum would need to be employed to distinguish between the two isomers.

References

- ↑ Alder, K., Stein, G.; Liebigs Ann. Chem.; 1933.; 504

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838. DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319[1]

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer., J. Am. Chem. Soc,, 1981,103DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ Pelayo Camps, Francesc Pérez and Santiago VázquezTetrahedron, 1997, 53, 9727. [2]

- ↑ B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H.S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ J. E. Baldwin., J. Chem. Soc. Chem, Commun.,, 1976,734DOI:10.1039/C39760000734

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 C. Laroche, S.M. Kerwin., J. Org. Chem.,,2009,74, 9229DOI:10.1021/jo902073m Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Laroche" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ K. Hiroya., R. Jouka., M. Kameda., T. Sakamoto Tetrahedron., 2001,57,734

- ↑ P. Schulte., U. Behrens., J. Chem. Soc. Chem, Commun.,1998,1633DOI:10.1039/A803791D

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 C. Praveen., C. Iyyappan., P. T, Perumal., Tetrahedron.,2010,51 (36), 4767 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Praveen" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ C. E. Dykstra., A. J. Arduengo., T. Fukunaga., J. Am. Chem. Soc.,1978,100 (19), 6007DOI:10.1021/ja00487a005