Rep:Ising:Yiming Xu

This experiment simulates a simple Ising model to explore phase transition phenomena. In addition to phase transition, various effects, such as paramagnetism, magnetic domains and spontaneous magnetization were observed. By simulating the Ising model with different lattice size at different temperatures, the curie temperature was obtained.

Theoretical Basis of the Ising Model

The Ising Model is a simple mathematical that allows simulation of magnetic moments in materials. The Square-Lattice (2D) version of the Ising Model is one of the simplest model to show a phase transition - being able to model both the energy of interaction as well as the entropy of interaction.

Introduction to the 2D Ising Model

The 2D Ising Model is usually implemented as a square lattice with periodic boundary condition. The boundary condition effectively restricts the geometry of the model to a torus. In the absence of a magnetic field, the only energetic contribution of the model comes from interactions between spins in adjacent lattice cells:

As periodic boundary condition is applied, the lattice is effectively infinite in extent and all cells are identical to each other. We thus only have to examine cell i with energy , and total energy , being an extensive property, will naturally be expressed as:

With the fraction of half due to double counting of each pair of interaction.

Intuitively, the lowest possible (most thermodynamically stable) energy state will occur if each term in the interaction energy summation is negative, i.e. has the same sign as and . This implies that the lattice must have identical spin throughout, either spin up or spin down, i.e. the spins must all be parallel. With two configurations, this would give a multiplicity of 2, and a total entropy of .

For each dimension, cell i gains two new neighbours. As from above, we have:

Substituting into the previous equation, we have:

Phase Transition in the Ising Model

In a phase transition, there often is a drastic change in the entropy of the system. At lower temperatures, this is “counteracted” by the increased total interaction energy that would be gained if the system was better packed and more “ordered”. The phase transition occurs at a temperature that balances the entropic force and the energetics, i.e.:

Therefore,

In the case of the Ising Model, we have being the interaction energy of the lattice, given by the equation above. The critical temperature T is the Curie temperature, T, at which the material loses magnetisation upon further heating.

Suppose the system is in the lowest energy transition, i.e. all spins are parallel. In order to move to a different state, one of the spins (e.g. cell i) must “flip”. As only interaction between neighbours contribute to the energy of the lattice, analysis can be limited to cell i and its immediate neighbours. Therefore:

Where is the flipped spin of cell i. As must necessarily be of same sign as , it must be of the opposite sign as . In 3-dimensions, cell i has 6 neighbours. This gives .

With 1 spin that is opposite to the other 999 spins in a 1000 spin system, we have a total of 2000 microstates (1000 for spin up and 1000 for spin down). Therefore,

Both 1D and 2D lattice shown in Figure 1 has total magnetisation of +1. At absolute zero, suppose the system of 1000 spins cooled slowly, remaining in thermal equilibrium, it will have a total magnetisation of +1000 or -1000.

Energy and Magnetisation of the Ising Model

For the class IsingLattice, energy() and magnetisation() have been initially implemented as below:

def energy(lattice):

"Return the total energy /k_b of the current lattice configuration."

#the following is the kernel for convolution for energy

energy_kernel = np.array([[0, 1, 0], [1, 0, 1], [0, 1, 0]])

#the following creates a (n+2, n+2) lattice with edges appended to create a

#effective periodic lattice for convolution

periodic_lattice = np.pad(lattice, 1, 'wrap')

#the following line creates a (n, n) lattice with the sum of unsigned energy

#of the neighbours

neighbour_energy_lattice = convolve2d(periodic_lattice, energy_kernel, mode='valid')

energy_lattice = neighbour_energy_lattice * lattice

energy = -0.5 * 1 * energy_lattice.sum()

return energy

def magnetisation(self):

"Return the total magnetisation of the current lattice configuration."

magnetisation = self.lattice.sum()

return magnetisation

IsingLattice.energy() was initially implemented as a 2D convolution due to realisation that the formula for the interaction energy was effectively the element-by-element product of each cell with the sum of its nearest neighbours. This was implemented over nested for-loops due to the expectation that the frequent use of convolution in image processing would lead to efficient built-in code.

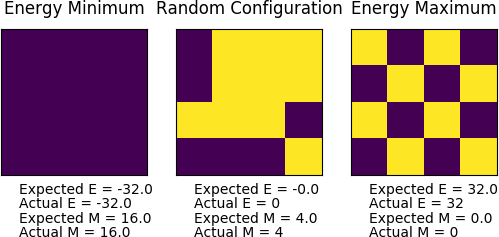

The accuracy of the both energy() and magnetisation() were verified to be correct, as shown by the figure below:

Introduction to the Monte Carlo Simulation

In a naive simulation, all configurations of the system would be sampled, and its energy and magnetisation evaluated. For a system with 100 spins, there are a total number of simulations. Suppose configurations can be evaluated each second, we would still need seconds, or approximately 40 trillion years, to evaluate all the positions to get . This is computationally impossible.

In order to make the simulation feasible, importance sampling using the Metropolis Monte-Carlo (MMC) method from the Boltzmann distribution () was used. This enables mostly microstates that are relevant to the thermodynamic properties to be selected. A simple implementation of the MMC algorithm can be found in the instructions from ChemWiki.

Modifying IsingLattice.py

The initial implementation of IsingLattice.montecarlostep(T) was shown below. self.E, self.E2, self.M and self.M2 were implemented as running sums instead of running averages to speed up computation. These were by the number of running cycles to give the average in IsingLattice.statistics().

def montecarlostep(self, T):

"This function performs a single Monte Carlo step and returns E and M"

self.n_cycles += 1

energy_old = self.energy()

lattice_old = self.lattice.copy()

#the following lines will flip a random spin

random_i = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_rows))

random_j = np.random.choice(range(0, self.n_cols))

self.lattice[random_i][random_j] *= -1

energy_new = self.energy()

deltaE = energy_new - energy_old

if deltaE > 0:

#choose a random number in the range [0,1) and test against Boltzmann

random_number = np.random.random()

if random_number > np.exp(-(deltaE)/(T)): #new configuration rejected

self.lattice = lattice_old

magnetisation_old = self.magnetisation()

#update running sum

self.E += energy_old

self.E2 += energy_old**2

self.M += magnetisation_old

self.M2 += magnetisation_old**2

return energy, self.magnetisation()

#if new configuration was accepted

magnetisation_new = self.magnetisation()

#update running sum

self.E += energy_new

self.E2 += energy_new**2

self.M += magnetisation_new

self.M2 += magnetisation_new**2

return energy_new, magnetisation_new

def statistics(self):

"This function returns E, E2, M, M2, and number of cycles"

cycles = self.n_cycles

return self.E/cycles, self.E2/cycles, self.M/cycles, self.M2/cycles, cycles

If , spontaneous magnetisation was expected as it minimizes the free energy - the lattice tends to be ordered with parallel spins in order to increase the interaction energy. The state of simulation given by ILanim.py can be found below:

Interestingly, the apparently equilibrium state does not always end up with parallel spins through the lattice. There are local minima in the configuration space that leads to paramagnetic phenomena - parts of the lattice points up, while other parts of the lattice points down. This is a local minima as flipping any single cell leads to an increase in energy. Given a long-enough simulation, however, the lattice may still evolve towards parallel spin.

Accelerating the Code

Anticipating large simulations IsingLattice.py was accelerated to a much greater extent than prescribed. The existing implementation was profiled using %%prun on Jupyter Notebook, and the data was used to inform on the focus of optimization.

Most of the time that was spent was running the functions energy() and montecarlostep(), with energy() taking up most of the calculation time. This was expected, as most of the computation were done in these two steps. Instead of ILtimetrial.py, %%timeit from iPython was used to evaluate different implementations of energy(). In order to offer a basis for comparison, identical lattice was used to test the computational efficiency of the functions. The various optimizations are detailed below, with the final code obtaining seconds in ILtimetrial.py on the computers on CHEM 232A.

Accelerating IsingLattice.energy()

The various implementations are detailed below. Each was initiated with an identical starting 8x8 lattice and profiled using %%timeit. The results and discussions are below the implementations.

def energy_test(lattice):

"Return the total energy /k_b of the current lattice configuration."

#the following is the kernel for convolution for energy

energy_kernel = np.array([[0, 1, 0], [1, 0, 1], [0, 1, 0]])

#the following creates a (n+2, n+2) lattice with edges appended to create a

#effective periodic lattice for convolution

periodic_lattice = np.pad(lattice, 1, 'wrap')

#the following line creates a (n, n) lattice with the sum of unsigned energy

#of the neighbours

neighbour_energy_lattice = convolve2d(periodic_lattice, energy_kernel, mode='valid')

energy_lattice = neighbour_energy_lattice * lattice

energy = -0.5 * 1 * energy_lattice.sum()

return energy

The results for energy_test() was 58.7 ms ± 2.25 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10 loops each). The small standard deviation show the precision involved in the test. The iniital implementation acts as a baseline for comparison.

def energy_test2(lattice):

energy = 0.0

#the following creates a (n+2, n+2) lattice with edges appended to create a

#effective periodic lattice

periodic_lattice = np.pad(lattice, 1, 'wrap')

(row, col) = lattice.shape

for i in range(1, row+1):

for j in range(1, col+1):

energy += periodic_lattice[i][j] * (periodic_lattice[i+1][j]+periodic_lattice[i][j+1]+periodic_lattice[i-1][j]+periodic_lattice[i][j-1])

return energy*-0.5

The results for energy_test2() was 2.05 s ± 52.3 ms per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 1 loop each). This was written for the test as a comparison to the naive double for-loop approach.

def energy_test3(lattice):

#np.roll was used as suggested in the script. np.multiply was shower than the implemented __mul__ in testing.

energy = lattice * np.roll(lattice, 1, axis = 0) + lattice * np.roll(lattice, 1, axis = 1)

return energy * -1

The results for energy_test3() was 10.4 ms ± 101 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each). This is significantly faster than the initial implementation using convolution. The fraction of was no longer necessary as each pair of interaction was included only once. In this case, cell i,j interacts with its left and top neighbour only. As all cells are identical, all pairs of interactions are accounted for.

def energy_test4(lattice):

#creates a new edge for periodic lattice calculation

periodic_lattice = np.pad(lattice, (0,1), 'wrap')

#sums up the neighbours down + right

sums = periodic_lattice[1:, :-1] + periodic_lattice[:-1, 1:]

return -(sums*lattice).sum()

The results for energy_test4() was 12.1 ms ± 62.2 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each). This implementation was written using insight from the previous implementation. However, the time was slightly longer possibly due to the need to recreate a new array while using np.pad().

def energy_test5(lattice):

"Return the total energy /k_b of the current lattice configuration."

#summing the energy from the top left cells

#down + right

lattice_mid = lattice[1:, :-1] + lattice[:-1, 1:]

sums = -(lattice_mid * lattice[:-1, :-1]).sum()

#summing the energy from the bottom edge

lattice_bottom = lattice[0, :-1] + lattice[-1, 1:]

sums -= (lattice_bottom * lattice[-1, :-1]).sum()

#summing the energy from the right edge

lattice_right = lattice[:-1, 0] + lattice[1:, -1]

sums -= (lattice_right * lattice[:-1, -1]).sum()

#summing the energy from the bottom right cell

sums -= lattice[-1, -1] * (lattice[-1, 0]+lattice[0, -1])

return sums

The results for energy_test5() was 5.38 ms ± 263 µs per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 100 loops each). This implementation was done by hard-coding the periodic boundary interactions, with each cell interaction with its right and down neighbour. This achieved significant speed increase compared to np.roll() due to the efficiency of the built-in numpy functions, and not creating new numpy arrays. The final IsingLattice.energy() was provided below, and was implemented by using more efficient summation functions within numpy, such as the Einstein summation and dot product.

def energy(self):

"Return the total energy /k_b of the current lattice configuration."

#summing the energy from the top left cells

#down + right

lattice_mid = self.lattice[1:, :-1] + self.lattice[:-1, 1:]

sums = -1 * np.einsum('ij,ij', lattice_mid, self.lattice[:-1, :-1])

#summing the energy from the bottom edge

lattice_bottom = self.lattice[0, :-1] + self.lattice[-1, 1:]

sums -= np.dot(lattice_bottom, self.lattice[-1, :-1])

#summing the energy from the right edge

lattice_right = self.lattice[:-1, 0] + self.lattice[1:, -1]

sums -= np.dot(lattice_right, self.lattice[:-1, -1])

#summing the energy from the bottom right cell

sums -= self.lattice[-1, -1] * (self.lattice[-1, 0] + self.lattice[0, -1])

return sums

Accelerating IsingLattice.montecarlostep()

IsingLattice.montecarlostep() was primarily only accelerated in one manner - by minimizing its call to other functions, especially computationally intensive functions such as energy(). numpy.random.choice() was replaced with numpy.random.randint() as randint() was more efficient in producing random integers.

In addition, calling of energy() was completed eliminated within montecarlostep(). This was achieved via the computing the initial energy of the lattice at instance initialization, keeping track of the current energy using a variable and then calculating the energy difference for each flip explicitly. The implementation is as below:

def montecarlostep(self, temperature):

"This function performs a single Monte Carlo step and returns E and M"

self.n_cycles += 1

energy_old = self.currentE

#the following lines will flip a random spin

random_i = np.random.randint(0, self.n_rows)

random_j = np.random.randint(0, self.n_cols)

#evaluating energy difference explicitly without evaluating entire grid

top_neighbour = (random_i-1)%self.n_rows

bot_neighbour = (random_i+1)%self.n_rows

lef_neighbour = (random_j-1)%self.n_cols

rig_neighbour = (random_j+1)%self.n_cols

neighbours = self.lattice[top_neighbour][random_j] + self.lattice[bot_neighbour][random_j] + self.lattice[random_i][lef_neighbour] + self.lattice[random_i][rig_neighbour]

energy_change = 2 * self.lattice[random_i][random_j] * neighbours

if energy_change > 0:

#choose a random number in the range [0,1) and test against Boltzmann

random_number = np.random.random()

if random_number > np.exp(-(energy_change)/temperature): #new configuration rejected

magnetisation_old = self.magnetisation()

#update running sum

self.E += energy_old

self.E2 += energy_old**2

self.M += magnetisation_old

self.M2 += magnetisation_old**2

return energy_old, magnetisation_old

#if new configuration accepted

self.lattice[random_i][random_j] *= -1

magnetisation_new = self.magnetisation()

energy_new = energy_old + energy_change #faster than calling energy()

self.currentE = energy_new #update energy variable

#update running sum

self.E += energy_new

self.E2 += energy_new**2

self.M += magnetisation_new

self.M2 += magnetisation_new**2

return energy_new, magnetisation_new

The Effect of Temperature

The effect of temperature were very significant on the course of the simulation. Temperature primarily affects the probability of a particle having sufficient energy to flip, whereas the lattice size determins the rate at which each flip affects the system. For example, flipping a single cell in a 2x2 lattice equates to flipping 25% of the entire system, and affects every other cell. On the other hand, a 128x128 lattice will take much longer simulation time in order for simulation to proceed.

From Figure 4, we can see that the trend described above holds true. As the lattice size increases, it takes an increasing amount of time for the system to reach equilibrium. While this can be attributed to simply having more cells, as above, a further effect can be seen from the 128x128 lattice - while the energy of the lattice has steadily decreased, the overall magnetisation per spin is still around 0. In addition, observing the lattice shows clusters of positive and negative spins.

The clustering of the spins reduces the overall energy, but the system need to shift towards one or the other to equilibriate. The equilibriating condition at low temperature is seen at Figure 4a, where the magnetisation per spin is 1. A metal-stable equilibrium as seen in Figure 4b, while having no further fluctuation, is far from the actual ground state, and simulation may need to run much longer to reach the true ground state. However, the energy per spin of the lattice is still close to the expected ground state value of -2.

In view of this result, it was decided to run the simulation for a long duration due to the speedup offered by acceleration. The runtime for simulation was determined to be 1000*n_cols*n_rows+300000 cycles, with the last 10000 cycles used for the statistics() function. This was implemented by keeping a list of the variables overtime, and taking the mean of last 10000 when statistics() is called.

From literature, the curie temperature, which is the phase transition of interest, lies at around It was decided to run the simulation at higher temperature step faraway from the temperature of interest, and a smaller timestep near the temperature of interest. The timesteps are:

- 0.2 for temperature of 0.25 - 1.2

- 0.1 for temperature of 1.2 - 1.7

- 0.05 for temperature of 1.7 - 2.1

- 0.025 for temperature of 2.1 - 2.4

- 0.05 for temperature of 2.4 - 2.8

- 0.1 for temperature of 2.8 - 3.3

- 0.2 for temperature of 3.3 - 5.0

Each run was automatically repeated 5 times with a different starting lattice by modifying the provided ILtemperaturerange.py. The modification will be provided in the appendix.

From Figure 5, it can be clearly seen that the errorbars increase near the peak in the middle. This is due to the larger fluctuations experienced by the system near the phase transition point - the curie temperature. The repeats capture the different possible starting configurations, and different cells that flip, as well as the different possible energy of the cells as given by the Boltzmann distribution.

Both the average energy of the lattice as well as the average absolute magnetisation of the 8x8 lattice is plotted against temperature. Both show an inflection point near , the expected curie temperature. was plotted instead of was due to the fact that the positive or negative sign of the lattice's magnetisation was not important, as the external magnetic field was simulated to be 0, only the magnitude was important in illustrating the phenomenon. The magnetisation of the lattice eventually tends to zero at high temperature past the curie temperature as the thermal energy is higher than the interaction energy of a stable parallel spin configuration.

The errorbar in the beginning shows the different starting configurations, and the fact that it takes a very long time to equilibriate at low temperatures (even at 364 000 cycles!. A longer simulation run, as well as a smaller temperature step, effectively works as a slower rate of temperature increase for the system. This was implemented to hopefully reduce errors found between systems.

The Effect of System Size

The effect of system size was extended to a 64x64 lattice in order to illustrate the points from insufficient equilibriation. From the section above, the average absolue magnetisation and its associated errors is a better estimator of the time taken for equilibriation to take place, the the errobar increased in magnitude as well as temperature (i.e. the starting error bars persisted through more temperatures) as the lattice size increased. This happened despite a 1000*N (where N is the number of spins) increase in the number of cycles. In all case, the errors in the average energy was much smaller.

The plots show a phase transition across all plots, but the inflection point in the graph was not obvious until a size of 8x8 was implemented. In all sizes, the errors increased near the curie temperature, showing significant fluctuations in the system. From the graphs, a lattice size of 8x8 should be minimally required to capture the long ranger fluctuations, whereas a 16x16 may be a good size to balance the computation required of the simulation, and the accuracy of the simulation.

Determining the Heat Capacity

The heat capacity at constant volume is defined as:

Experimentally, the heat capacity can be found by adding a measured amount of heat into the system. However, computationally it may also be investigated from its relationship to the thermal energy of the system - under thermal equilirium, a system with higher heat capacity will have lesser fluctuation in its average energy. This can be seen from statistical physics:

In the simulation, the system runs under the canonical ensemble (NVT). In such an ensemble, we have our average energy,

where is the partition function, and are the different discrete energy levels of the system.

The average energy is well known, and is commonly expressed as the log of the partition function,

and,

On the other hand, we have the variance of energy,

From above, we can then relate the variance with the partition function,

Rearranging, we have, Using the formula determined, the heat capacity can be found and plotted as following:

From Figure 7, it can be seen that for lower lattice sizes (2x2 to 8x8), the peak of heat capacity near the curie temperature becomes increasingly prominant, with the spread of the graph getting narrower. However, for graphs of 16x16 onwards, the heat capacity near the transition point becomes less sharp. This could be due to insufficient equilibration. While the runs may be nominally sufficient for the previous temperatures before that, it may be the fact that it was in the true ground state and thus does not react to the heat increase in time.

A similar procedure was used to establish the magnetic susceptiblity of the lattice at different lattice size and temperatures. A similar trend was seen as compared to the heat capacity, but it was more obvious that the 8x8 lattice shows the best response to the simulation under the current conditions.

Locating the Curie temperature

The data simulated was obeys that simulated by the C++ data in this case. The agreement decreases as the lattice size increases, especially near the critical region. A 16x16 lattice was fitted with a 10 degree polynomial to estimate its height. While a higher degree polynomial should always fit better, the 10 degree was chosen due to it being able to at least fit the region away from the critical point. A comparison is provided below:

While the fit may seem reasonable for the Python simulated data on first glance, repeating the proedure for C++ data shows its inadequecies. A better result may be achieved by limiting the range of temperature fitted.

In addition to the fit being better within the range, a lower degree of polynomial would be sufficient to generate a reasonable fit.

While the curie temperature of the different lattice can be identified, they are not yet the true curie temperature of the material, which has an effectively infinite lattice. The curie temperature of an infinite lattice can be found by the following relationship:

Using the equation, the curie temperatures of the different lattice sizes were plotted agains the reciprocal of the lattice length to give . This is in very good agreement with a literature value of 2.27.

One major advantage of obtaining curie temperature by the peak of the lattice was that the system need not have reached equilibrium for the technique to work. The system merely has to respond to it being at the curie temperature at that point in time. This implies that the lattice need not be run to equilibrium to obtain a relatively accurate value.

Sources of Error and Further Improvements

One major source of error was the limited run time and lattice size that we were able to achieve. Run time, lattice size and computational efficiency goes hand in hand - a more efficient simulation will be able to run bigger lattice, for more simulation cycles for shorter real time, making it more feasible. Without sufficient run time, the system was often not in its equilibrium state and are not able to provide accurate representations of reality, by giving different thermodynamic values than otherwise expected. One way to resolve this was to speed up the IsingLattice class - by writing more efficient code in Python, porting it to Cython or as done in the instruction manual, do it in a compiled language such as C++. However, this is a naive solution - if the simulation algorithm was not efficient, this would still be a waste of computing resources. One critical slow down in approaching equilibria is when the system gets stuck in a local minimum. This may be partially resolved by adopting a different algorithm - the Wolff cluster algorithm to speed up the simulation at lower temperatures. Another way to avoid the local minima would be to adopt algorithm that do not 'see' the roughness in the energy landscape, by possibly flipping multiple spins at once. Another source of error was the fit used, which was simply polynomial. With the knowledge that a transition temperature was observed, a more suitable function may be fit to the critical point to obtain a more precise value of curie temperature.

Appendix

IsingLattice.py

'''

This module implements a 2D Ising Model with a simple Metropolis Monte-Carlo

Simulation (MMC Simulation). Lattice is implemented with Periodic Boundary

Condition (PBC)

Example:

$ from IsingLattice import IsingLattice

Attributes:

There are no module level attributes.

Todo:

* Implementing additional helper class

* Breaking up the IsingLattice class

'''

import numpy as np

class IsingLattice:

'''

Args:

n_rows (int): The number of rows of the lattice to be simulated

n_cols (int): The number of columns of the lattice to be simulated.

Attributes:

n_rows (int): The number of rows of the lattice to be simulated

n_cols (int): The number of columns of the lattice to be simulated.

lattice (numpy.ndarray): The 2D Ising Model lattice

int_energy (float): The interaction energy between particles

E (float): The running sum of the energy over equilibrated simulation

E2 (float): The running sum of the energy squared over

equilibrated simulation

M (float): The running sum of the magnetisation over

equilibrated simulation

M2 (float): The running sum of the magnetisation squared over

equilibrated simulation

n_cycles (int): The number of cycles of simulations that were carried out

equilibriation_time (int): The estimated (worst case) cycles that the system

would require to equilibrate

'''

# pylint: disable=too-many-instance-attributes, line-too-long

def __init__(self, n_rows, n_cols):

self.n_rows = n_rows

self.n_cols = n_cols

self.lattice = np.random.choice([-1, 1], size=(n_rows, n_cols))

self.int_energy = 1.0

#the following 4 variables are running sums

self.E = 0.0

self.E2 = 0.0

self.M = 0.0

self.M2 = 0.0

self.data_all = [[], [], [], []] #keeping track of running statistics

self.n_cycles = 1

self.currentE = self.energy() #initialize initial energy

self.equilibration_time = 1000*n_cols*n_rows #time it takes to reach equilibria

def energy(self):

"Return the total energy /k_b of the current lattice configuration."

#summing the energy from the top left cells

#down + right

lattice_mid = self.lattice[1:, :-1] + self.lattice[:-1, 1:]

sums = -1 * np.einsum('ij,ij', lattice_mid, self.lattice[:-1, :-1])

#summing the energy from the bottom edge

lattice_bottom = self.lattice[0, :-1] + self.lattice[-1, 1:]

sums -= np.dot(lattice_bottom, self.lattice[-1, :-1])

#summing the energy from the right edge

lattice_right = self.lattice[:-1, 0] + self.lattice[1:, -1]

sums -= np.dot(lattice_right, self.lattice[:-1, -1])

#summing the energy of the bottom right cell

sums -= self.lattice[-1, -1] * (self.lattice[-1, 0] + self.lattice[0, -1])

return sums

def magnetisation(self):

"Return the total magnetisation of the current lattice configuration."

magnetisation = self.lattice.sum()

return magnetisation

def montecarlostep(self, temperature):

"This function performs a single Monte Carlo step and returns E and M"

self.n_cycles += 1

energy_old = self.currentE

#the following lines will flip a random spin

random_i = np.random.randint(0, self.n_rows)

random_j = np.random.randint(0, self.n_cols)

#evaluating energy difference explicitly without evaluating entire grid

top_neighbour = (random_i-1)%self.n_rows

bot_neighbour = (random_i+1)%self.n_rows

lef_neighbour = (random_j-1)%self.n_cols

rig_neighbour = (random_j+1)%self.n_cols

#summing up the contribution by the neighbours

neighbours = self.lattice[top_neighbour][random_j] + self.lattice[bot_neighbour][random_j] + self.lattice[random_i][lef_neighbour] + self.lattice[random_i][rig_neighbour]

energy_change = 2 * self.lattice[random_i][random_j] * neighbours

if energy_change > 0:

#choose a random number in the range [0,1) and test against Boltzmann

random_number = np.random.random()

if random_number > np.exp(-(energy_change)/temperature): #new configuration rejected

magnetisation_old = self.magnetisation()

#if self.n_cycles > self.equilibration_time:

self.E += energy_old

self.E2 += energy_old**2

self.M += magnetisation_old

self.M2 += magnetisation_old**2

self.data_all[0].append(energy_old)

self.data_all[1].append(energy_old**2)

self.data_all[2].append(magnetisation_old)

self.data_all[3].append(magnetisation_old**2)

return energy_old, magnetisation_old

#if new configuration is accepted

self.lattice[random_i][random_j] *= -1

magnetisation_new = self.magnetisation()

energy_new = energy_old + energy_change #faster than calling energy()

self.currentE = energy_new #update the current running count

#if self.n_cycles > self.equilibration_time:

self.E += energy_new

self.E2 += energy_new**2

self.M += magnetisation_new

self.M2 += magnetisation_new**2

self.data_all[0].append(energy_new)

self.data_all[1].append(energy_new**2)

self.data_all[2].append(magnetisation_new)

self.data_all[3].append(magnetisation_new**2)

return energy_new, magnetisation_new

def statistics(self):

"This function returns E, E2, M, M2, and number of cycles. Function will return 0 if running time is less than equilibration time."

#return last 10000 cycles

data = np.array(self.data_all)

#return everything is <10000 cycles have been run

if len(data[0]) < 10000:

return np.average(data[0]), np.average(data[1]), np.average(data[2]), np.average(data[3]), self.n_cycles

return np.average(data[0][-10000:]), np.average(data[1][-10000:]), np.average(data[2][-10000:]), np.average(data[3][-10000:]), self.n_cycles

ILtemperaturerange.py

import sys

from IsingLattice import *

from matplotlib import pylab as pl

import numpy as np

from IPython.display import clear_output

dimensions = 8 #default

print(len(sys.argv))

if len(sys.argv) > 1:

dimensions = int(sys.argv[1])

n_rows = dimensions

n_cols = dimensions

runtime = 1000*n_cols*n_rows+300000

if len(sys.argv) == 3:

runtime = int(sys.argv[2])

il = IsingLattice(n_rows, n_cols)

spins = n_rows*n_cols

times = range(runtime)

temps = np.arange(0.25, 1.2, 0.2)

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(1.2, 1.7, 0.1)]

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(1.7, 2.1, 0.05)]

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(2.1, 2.4, 0.025)]

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(2.4, 2.8, 0.05)]

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(2.8, 3.3, 0.1)]

temps = np.r_[temps, np.arange(3.3, 5.0, 0.2)]

for repeat in [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]:

il.lattice = np.ones((n_rows, n_cols))

energies = []

magnetisations = []

energysq = []

magnetisationsq = []

for t in temps:

for i in times:

if i % 100000 == 0:

clear_output()

print(t, i, "out of", runtime, "of repeat", repeat)

energy, magnetisation = il.montecarlostep(t)

aveE, aveE2, aveM, aveM2, n_cycles = il.statistics()

energies.append(aveE)

energysq.append(aveE2)

magnetisations.append(aveM)

magnetisationsq.append(aveM2)

#reset the IL object for the next cycle

il.E = 0.0

il.E2 = 0.0

il.M = 0.0

il.M2 = 0.0

il.n_cycles = 0

for i in il.data_all:

i.clear()

final_data = np.column_stack((temps, energies, energysq, magnetisations, magnetisationsq))

np.savetxt("{0}x{0}_rep{1}.dat".format(dimensions, repeat), final_data)

fig = pl.figure(figsize=(10,15))

enerax = fig.add_subplot(2,1,1)

enerax.set_ylabel("Energy per spin")

enerax.set_xlabel("Temperature")

enerax.set_ylim([-2.1, 2.1])

magax = fig.add_subplot(2,1,2)

magax.set_ylabel("Magnetisation per spin")

magax.set_xlabel("Temperature")

magax.set_ylim([-1.1, 1.1])

enerax.plot(temps, np.array(energies)/spins)

magax.plot(temps, np.array(magnetisations)/spins)

pl.show()

Graph Plotting and Analysis Notebook

# coding: utf-8

# In[78]:

get_ipython().run_line_magic('pylab', 'inline')

import os

params = {'legend.fontsize': 'x-large',

'figure.figsize': (15, 10),

'axes.labelsize': 'x-large',

'axes.titlesize':'xx-large',

'xtick.labelsize':'x-large',

'ytick.labelsize':'x-large'}

rcParams.update(params)

# # Data Input and Processing

# In[100]:

#py_data = [[lattice_size], np.array([[lattice_size_rep1], [lattice_size_rep2]])]

py_data = {}

c_data = {}

#get datafiles

py_filenames = [x for x in os.listdir() if (x.endswith(".dat") and 'rep' in x)]

c_filenames = [x for x in os.listdir(".\C++_data") if x.endswith(".dat")]

#sort datafiles by lattice size

py_filenames.sort(key = lambda x: int(x.split('x')[0]))

c_filenames.sort(key = lambda x: int(x.split('x')[0]))

#reading data from files and storing in py_data

for file in py_filenames:

lattice_size = int(file.split('x')[0])

if lattice_size not in py_data:

py_data[lattice_size] = []

file_data = np.loadtxt(file)

heat_capacity_per_spin = (file_data[:,2]-file_data[:,1]**2)/(file_data[:,0]**2 * lattice_size**2)

magnetic_susceptibility_per_spin = (file_data[:,4]-file_data[:,3]**2)/(file_data[:,0] * lattice_size**2)

py_data[lattice_size].append(np.c_[file_data, heat_capacity_per_spin, magnetic_susceptibility_per_spin])

#reading data from files and storing in c_data

for file in c_filenames:

lattice_size = int(file.split('x')[0])

file_data = np.loadtxt(".\\C++_data\\" + file)

magnetic_susceptibility_per_spin = (file_data[:,4]-file_data[:,3]**2)/(file_data[:,0]) * lattice_size**2

c_data[lattice_size] = np.c_[file_data, magnetic_susceptibility_per_spin]

#changing list to ndarray for ease of computation

for i in py_data:

py_data[i] = array(py_data[i])

py_data[i][:,:,3] = abs(py_data[i][:,:,3])

lattice_mean = mean(py_data[i], axis = 0)

lattice_stderr = std(py_data[i], axis = 0)/(5**0.5)

py_data[i] = np.c_[lattice_mean, lattice_stderr[:,1:]]

for i in c_data:

c_data[i] = array(c_data[i])

# # Python Simulated Data

# In[98]:

for i in py_data:

errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,5], yerr=py_data[i][:,-2], label = '{0}x{0}'.format(i))

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

xlabel('Temperature')

legend()

show()

# In[99]:

for i in py_data:

errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,6], yerr=py_data[i][:,-1], label = '{0}x{0}'.format(i))

ylabel('Magnetic Susceptibility per Spin')

xlabel('Temperature')

legend()

show()

# In[42]:

#8x8 thermodynamic properties

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots()

ax1.errorbar(py_data[8][:,0], py_data[8][:,5], yerr=py_data[8][:,-2], ls = '', marker = 'x', color='b', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(8))

ax1.set_xlabel('Temperature')

ax1.set_ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin', color='b')

ax1.tick_params('y', colors='b')

ax2 = ax1.twinx()

ax2.errorbar(py_data[8][:,0], py_data[8][:,6], yerr=py_data[8][:,-1], ls = '', marker = 'x', color='r', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(8))

ax2.set_ylabel('Magnetic Susceptibility per Spin', color='r')

ax2.tick_params('y', colors='r')

plt.show()

# In[57]:

#8x8 simulation properties

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots()

ax1.errorbar(py_data[8][:,0], py_data[8][:,1], yerr=py_data[8][:,-6], ls = '', marker = 'x', color='b', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(8))

ax1.set_xlabel('Temperature')

ax1.set_ylabel('Average Energy', color='b')

ax1.tick_params('y', colors='b')

ax2 = ax1.twinx()

ax2.errorbar(py_data[8][:,0], py_data[8][:,3], yerr=py_data[8][:,-4], ls = '', marker = 'x', color='r', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(8))

ax2.set_ylabel('Average Absolute Magnetisation', color='r')

ax2.tick_params('y', colors='r')

plt.show()

# In[90]:

#plot all the lattice with their simulation properties

figure(figsize=(30, 24))

plotpos = 1

for i in py_data:

subplot(6, 2, plotpos)

ax1 = plt.gca()

ax1.errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,1]/(i**2), yerr=py_data[i][:,-6]/(i**2), ls = '', marker = 'o', color='b', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(i))

ax1.set_xlabel('Temperature')

ax1.set_ylabel('Average Energy per Spin', color='b')

ax1.tick_params('y', colors='b')

ax2 = ax1.twinx()

ax2.errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,3]/(i**2), yerr=py_data[i][:,-4]/(i**2), ls = '', marker = 'x', color='r', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(i))

ax2.set_ylabel('Average Absolute Magnetisation per Spin', color='r')

ax2.tick_params('y', colors='r')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[123]:

#plot all the lattice

i = 4

errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,5], yerr=py_data[i][:,-2], ls = '', marker = 'x', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(i))

plot(c_data[i][:,0], c_data[i][:,5], ls = '-', label = "{0}x{0} C++ data".format(i))

ylabel('heat Capacity per Spin', color='b')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

show()

# In[112]:

#plot all the lattice

figure(figsize=(30, 24))

plotpos = 1

for i in py_data:

subplot(6, 2, plotpos)

errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,5], yerr=py_data[i][:,-2], ls = '', marker = 'x', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(i))

plot(c_data[i][:,0], c_data[i][:,5], ls = '-', label = "{0}x{0} C++ data".format(i))

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[180]:

figure(figsize=(15,24))

plotpos = 1

#plot the same lattice size

for i in py_data:

subplot(6, 1, plotpos)

errorbar(py_data[i][:,0], py_data[i][:,6], yerr=py_data[i][:,-1], ls = '', marker = 'x', label = "{0}x{0} simulated data".format(i))

plot(c_data[i][:,0], c_data[i][:,6], ls = '-', label = "{0}x{0} C++ data".format(i))

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Magnetic Susceptibility per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[140]:

T = c_data[16][:,0] #get the first column

C = c_data[16][:,5] # get the second column

#first we fit the polynomial to the data

fit = np.polyfit(T, C, 10) # fit a third order polynomial

#now we generate interpolated values of the fitted polynomial over the range of our function

T_min = np.min(T)

T_max = np.max(T)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000) #generate 1000 evenly spaced points between T_min and T_max

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range) # use the fit object to generate the corresponding values of C

plot(T, C, ' x')

plot(T_range, fitted_C_values, '-')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

show()

# In[155]:

plotpos = 1

labels = ['Simulated Data', 'C++ Data']

for i in [py_data, c_data]:

subplot(2, 1, plotpos)

T = i[8][:,0] #get the first column

C = i[8][:,5] # get the second column

#first we fit the polynomial to the data

fit = np.polyfit(T, C, 10)

#now we generate interpolated values of the fitted polynomial over the range of our function

T_min = np.min(T)

T_max = np.max(T)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000) #generate 1000 evenly spaced points between T_min and T_max

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range) # use the fit object to generate the corresponding values of C

plot(T, C, ' x', label = labels[plotpos-1])

plot(T_range, fitted_C_values, '-', label = 'Fit Data')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[159]:

plotpos = 1

labels = ['Simulated Data', 'C++ Data']

for i in [py_data, c_data]:

subplot(2, 1, plotpos)

T = i[8][:,0] #get the first column

C = i[8][:,5] # get the second column

#now we generate interpolated values of the fitted polynomial over the range of our function

T_min = np.min(1.7)

T_max = np.max(2.8)

selection = np.logical_and(T > T_min, T < T_max) #choose only those rows where both conditions are true

peak_T_values = T[selection]

peak_C_values = C[selection]

#we fit the polynomial to the data

fit = np.polyfit(peak_T_values, peak_C_values, 3)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000) #generate 1000 evenly spaced points between T_min and T_max

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range) # use the fit object to generate the corresponding values of C

plot(T, C, ' x', label = labels[plotpos-1])

plot(T_range, fitted_C_values, '-', label = 'Fit Data')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[185]:

figure(figsize = (15,30))

plotpos = 1

py_cmax = [[],[]]

for i in py_data:

subplot(6, 1, plotpos)

T = py_data[i][:,0] #get the first column

C = py_data[i][:,5] # get the second column

#now we generate interpolated values of the fitted polynomial over the range of our function

T_min = np.min(1.7)

T_max = np.max(2.8)

selection = np.logical_and(T > T_min, T < T_max) #choose only those rows where both conditions are true

peak_T_values = T[selection]

peak_C_values = C[selection]

#we fit the polynomial to the data

fit = np.polyfit(peak_T_values, peak_C_values, 3)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000) #generate 1000 evenly spaced points between T_min and T_max

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range) # use the fit object to generate the corresponding values of C

#get curie temperature

Cmax = np.max(fitted_C_values)

Tmax = T_range[fitted_C_values == Cmax]

py_cmax[0].append(i)

py_cmax[1].append(Tmax)

plot(T, C, ' x')

plot(T_range, fitted_C_values, '-', label = 'Fit Data')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[213]:

py_cmax = array(py_cmax)

fit, cov_fit = np.polyfit(1/py_cmax[0], py_cmax[1], 1, cov = True)

plot_range = np.linspace(0, 0.5, 1000)

fitted_C = np.polyval(fit, plot_range)

plot(1/py_cmax[0], py_cmax[1], ' x')

plot(plot_range, fitted_C, '-')

text(0.3, 2.4, r'$y = {:.1f}\pm{:.1f}x + {:.2f}\pm{:.2f}$'.format(fit[0], sqrt(cov_fit[0][0]), fit[1], sqrt(cov_fit[1][1])), fontsize=15)

legend()

xlabel('1/L')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

show()

# In[237]:

figure(figsize = (15,30))

plotpos = 1

py_mmax = [[],[]]

for i in py_data:

subplot(6, 1, plotpos)

T = py_data[i][:,0] #get the first column

C = py_data[i][:,6] # get the second column

#now we generate interpolated values of the fitted polynomial over the range of our function

T_min = np.min(1.5)

T_max = np.max(3.5)

selection = np.logical_and(T > T_min, T < T_max) #choose only those rows where both conditions are true

peak_T_values = T[selection]

peak_C_values = C[selection]

#we fit the polynomial to the data

fit = np.polyfit(peak_T_values, peak_C_values, 3)

T_range = np.linspace(T_min, T_max, 1000) #generate 1000 evenly spaced points between T_min and T_max

fitted_C_values = np.polyval(fit, T_range) # use the fit object to generate the corresponding values of C

#get curie temperature

Cmax = np.max(fitted_C_values)

Tmax = T_range[fitted_C_values == Cmax]

py_mmax[0].append(i)

py_mmax[1].append(Tmax)

plot(T, C, ' x')

plot(T_range, fitted_C_values, '-', label = 'Fit Data')

legend()

xlabel('Temperature')

ylabel('Magnetic Susceptibility per Spin')

plotpos += 1

show()

# In[238]:

py_mmax = array(py_mmax)

fit, cov_fit = np.polyfit(1/py_mmax[0], py_mmax[1], 1, cov = True)

plot_range = np.linspace(0, 0.5, 1000)

fitted_C = np.polyval(fit, plot_range)

plot(1/py_mmax[0], py_mmax[1], ' x')

plot(plot_range, fitted_C, '-')

text(0.3, 2.4, r'$y = {:.1f}\pm{:.1f}x + {:.2f}\pm{:.2f}$'.format(fit[0], sqrt(cov_fit[0][0]), fit[1], sqrt(cov_fit[1][1])), fontsize=15)

legend()

xlabel('1/L')

ylabel('Heat Capacity per Spin')

show()