Rep:HSC1296

Free Energy and Thermal Expansion of MgO

Introduction

This lab is an investigation into the energy and vibrations of the crystal structure of MgO, in order to understand more specifically the dynamics of atoms in the lattice to explain changes in the structure during thermal expansion. The use of lattice dynamics is important when investigating temperature related characteristics in solids as the change in motion of the atoms when heated is what must be understood in order to explain them.

The structure of MgO is a face centered cubic lattice, represented as a primitive cell of just two atoms in a rhombohedron, or a conventional cell of 8 atoms arranged in a cube.

In a solid crystal structure, we must think in reciprocal space. This can be defined as a Fourier transform of real space. In an infinite lattice structure, there are infinite electronic energy levels, each can be described by a wavefunction. A Bloch function calculates the wavefunction as a symmetry adapted linear combination, for atoms in the solid state: ψk = Σn einak Χn.

k is a quantity described as a wave vector that essentially allows the labeling of these energy levels. Each value of ±k represents a degenerate pair of levels. When we plot E(k) against k, with Γ at the origin in reciprocal space, we get a function with a periodicity of a*=2π/a, where a is the lattice parameter between the atoms. This is known as a band structure, and for a solid takes on a cosine shape. The lattice parameter, a, can also be thought of as the periodicity in real space. Note that n AO's in a unit cell combine to form n MO's, which equates to n bands in the band structure. There are only unique values of k between -π/a and π/a, which is known as the Brillouen zone. A phonon dispersion curve is a band structure representing vibrational energy levels, it is a plot of k values against vibrational frequency (ω).

We use the Bloch function to calculate the energy of phonons (quanta of vibrational energy), as a function of k. In 3D, the E(k) plotted is E(kx, ky, kz). We use a 'grid' of k values to compute density of state diagrams, which show the number of each energy level present. The larger the grid, the more k values and the more energy levels are represented. In this experiment, we must find the minimum k grid that shows a good approximation.

To calculate the free energy, we can sum over all vibrational energy levels and all k values. This is known as a quasi-harmonic (QH) approximation, which applies the harmonic approximation for all varied values of the lattice constant and will be compared to a molecular dynamic calculation of the free energy. This simulates in the computer the velocities of the atoms at specified temperatures, using Newton's second law: F = m × a. Molecular dynamics uses a supercell of 64 atoms.

The software used is DLVisualise and the program GULP to carry out various calculations and simulations.

Method

To begin with, the total energy per unit cell was calculated via a single point calculation, using a simple Buckingham potential to approximate short range interatomic forces. This energy can be described as the energy required for all atoms in the lattice to be moved to an infinite internuclear separation.

Next, the phonon dispersion curve was computed, under the same potential to approximate interatomic forces.

The phonon density of state (DOS) diagrams were computed for k grids of 1×1×1, 2×2×2, 4×4×4, 8×8×8, 16×16×16 and 32×32×32. The smaller grid sizes show peaks, and therefore areas on the graph imply that there are zero states of some energies, which is too large of an approximation. The larger the grid size, the smoother the DOS curve.

The free energy was computed within the quasi-harmonic approximation, using the same series of k grids as above. The grid size of 16 x 16 x 16 gave the free energy to an accuracy of within 0.1 meV, and was therefore used to investigate the change in free energy with increasing temperature.

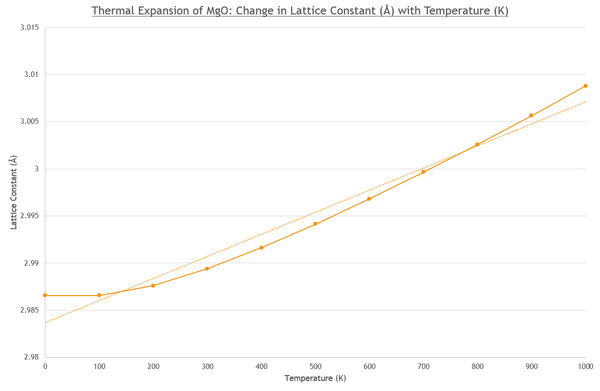

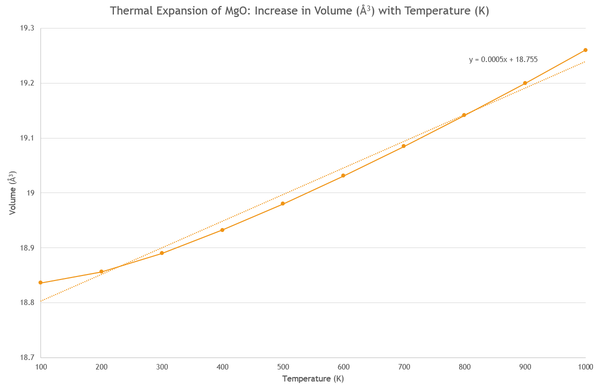

The Helmholtz free energy was optimized at temperatures of 0 - 1000 K in 100 K intervals. The lattice constant (Å) and unit cell volume (Å3) for the primitive cell was also recorded at each temperature, and plotted separately against temperature in order to calculate a thermal expansion coefficient.

Finally, molecular dynamics was computed to obtain the volumes, in order to compare the values and methods of obtaining thermal expansion coefficients. The atoms are originally in the initial configuration of ideal MgO with velocities matched to the temperature specified.

- Force and acceleration of the atoms is computed.

- The velocities are then updated so that:

- The positions of the atoms are updated with the new velocities.

- This is repeated until average energies and temperatures are settled so that the final cell volume can be recorded.

Results and Discussion

Calculating the phonon modes of MgO

The phonon dispersion curve in Fig. 1 plots k values against frequency of vibrations. For a diatomic solid we can expect to see the branch diagram 'folded' to show many different acoustic and optic branches. There are the same number of branches as there are AOs. Each branch represents a different vibration of the atoms, moving each in a particular direction. Optic branches represent vibrations of a frequency in the optic region of the electromagnetic spectrum, and atoms vibrate as they would in an oscillating electromagnetic field. Acoustic branches represent vibrations that have an acoustic frequency, and can be transverse of longitudinal. At k = 0, all atoms move with the same vibration in the same direction - it mimics a translation.

Computing the free energy within the quasi-harmonic approximation

In order to compute the quasi-harmonic approximation of the Helmholtz free energy, we must sum the vibrational modes over all bands and k values. In order to approximate this numerically, we must use a finite number of k values that shows a good approximation to the true value. As the number of k values increases, the free energy converges to one value at 300K, (Table 1). The difference between the free energy of k grids 32×32×32 and 16×16×16 is -1×10-6, so the 16 grid gives a good compromise of accuracy to 0.1 meV. This will be sufficient for the crystal lattice of MgO, and would be the same for other diatomic solids, provided the atoms were of a similar size, or nearby in the periodic table. In comparison, a crystal of Faujasite has a much larger unit cell, so a larger value of a (lattice parameter) in real space, and therefore a smaller value of a* = 2π/a (reciprocal space equivalent). In this case a 'smaller' k-grid would be necessary for the same degree of convergence. On the other hand, a solid such as Lithium metal has a smaller unit cell consisting of just one atom, so a* is larger and a 'larger' k-grid would be necessary.

The table below shows computed optimised free energies at different sizes of k-grids, referring to the number of k points. The free energy converged with increasing k grid size to a value of -40.9265 eV.

| k-grid | Helmholtz Free Energy (eV) |

|---|---|

| 1×1×1 | -40.930301 |

| 2×2×2 | -40.926609 |

| 4×4×4 | -40.926450 |

| 8×8×8 | -40.926478 |

| 16×16×16 | -40.926482 |

| 32×32×32 | -40.926483 |

Once the optimum grid size of 16×16×16 was found, it was used to optimize the Helmholtz free energy for temperatures from 0-1000K at intervals of 100K. The data was plotted and the graph is shown in Figure 8. A clear trend is seen where as the temperature increases, the Helmholtz free energy decreases, with a quadratic line of best fit of the equation y = -4×10-07x2 + 2×10-05x - 40.899. This shows that as the temperature is increased from 0K, the crystal's structure becomes more thermodynamically stable.

The thermal expansion of MgO

It can also be seen from Figure 9 that as the temperature increases, the lattice constant becomes larger, the atoms become further apart and therefore the volume of the primitive cell increases (Figure 10). After a temperature of 300K, the trend in data is linear for both lattice constant increase (Fig. 9) and volume increase (Fig. 10), as the increase occurs slower at lower temperatures. Over a larger temperature range this is less noticable[6], and the temperature range does not span toward the crystal's melting point of 3250K ±20K [7].

Using this data it is possible to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO. This is a measure of the fraction of change in size of a substance, per degree change in temperature and is calculated using the following equation: To approximate to a linear thermal expansion coefficient, we use the gradient from the linear line of best fit on the graph showing volume vs. temperature. As the gradient does not change with temperature, the coefficient applies to all temperatures. Note that for isotropic solids such as MgO:

This is approximated as we can see from the graph (Fig. 10) that the linear line of best fit does not go through all points, a more accurate line is given in Fig. 11 y = 2×10-07x2 + 0.0002x + 18.802.

Therefore

at 300K:

However from literature, values range from 9 K-1 to 12 K-1 [8].

Molecular dynamics

We will now compare the results from the molecular dynamics calculations by calculating the thermal expansion coefficient. The molecular dynamics calculations use classical physics, and uses the Newton's law of motion F=ma to find the average force over all atoms in a super cell of 64 atoms in total. A larger cell is required to get an accurate picture of how the atoms' movements affect eachother, as in a primitive cell of just two atoms, the dynamics around each atom would not be accounted for. This force is then distributed randomly over all atoms, giving an energy of displacement for each atom on the movements. which can be simulated as the atoms follow their trajectory to show the movement of atoms on DLVisualise. The output gives final cell volumes of the super cell, and so these must be divided by eight to get the volume of a conventional cell (eight atoms) and again by four to reach the volume of a primitive cell in order to compare with QH data. Fig. 12. shows the graph of increase in cell volumes with temperature, again at intervals of 100 K-1000 K. Data for molecular dynamics cannot be recorded at 0 K as atoms will have no kinetic energy according to classical physics.

The thermal expansion coefficient can now be calculated in the same way as before, using the gradient from the graph.

This figure lies within the range of literature values, indicating it is a more accurate method of computing the lattice dynamics. It follows that at higher temperatures, the classical method of molecular dynamics gives a better representation than the quantum mechanical QH as when temperature increases, movements become at a higher acceleration and higher force, the displacement of each atom becomes larger, eventually causing them to take on a the higher energy dynamics associated with the liquid state. This would not be accurately represented in the QH approximation due to the parabolic curve that approximates that at larger internuclear separation, the energy increases toward , as displayed in fig. 13. However, at lower temperatures, the quantum mechanical approach is more accurate, as it disputes the classical theory that particles at 0 K have no kinetic energy. In fact, at 0 K, particles contain a finite amount of energy that is always present, known as the zero point energy. This is due to the uncertainty principle, which states that at no point in time can the momentum of a particle be known as well as its position, and that the more we know about one, the less we know about the other.

Conclusion

In this experiment, two very different calculation methods were used to find a thermal expansion coefficient of the crystal MgO. In the first method, a quasi-harmonic approximation (QH) uses a quantum mechanical theory applying a Lennard Jones potential to the atoms, and approximating this into a parabola. It demonstrates how higher energy levels are populated at higher temperatures, meaning a change in the equilibrium position (the minimum). There is more approximated in this method, as the energy and volumes are calculated by optimising the free energy, using 16×16×16 grid of k-points. In real life these points are infinite, so it may have been more accurate to use a larger k-grid, however this would have taken more time. This method is more reliable at lower temperatures as it takes into account the zero-point energy of the atoms at 0 K. My thermal expansion coefficient from this method was outside the literature range. If I had more time, I would carry out the same calculations on a conventional cell and see if these results varied at all.

The second method used molecular dynamics to simulate actual vibrations of atoms modelled on Newton's Law of motion F=ma. A cell of 64 atoms was used in this experiment, however to achieve a more real representation of the dynamics at higher temperatures, an even larger cell would be required. This would take more time and more advanced computers to carry out, but would give a better description of e.g. melting. This method is not as accurate at lower temperatures, as we can see from Fig. 14, the data was much more linear, as this method states that at 0 K all atoms have no kinetic energy. However, my results show that this method achieved a thermal expansion coefficient nearer to the literature value, I believe this is due to the larger cell used and the average force being distributed over more atoms to allow for random motion as well.

[1] Bush, T. S., Gale, J. D., Catlow, C. R. a., & Battle, P. D. (1994). Self-consistent interatomic potentials for the simulation of binary and ternary oxides. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 4

[2] Christi, M. Y. (1989). Some fundamentals. Airlift Bioreactors, 12–32.

[3] Dove, M. T. (2016). Dynamics of diatomic crystals : general principles, 36–54.

[4] Dove, M. T. (2016). The harmonic approximation and lattice dynamics of very simple systems, 18–35.

[5] Durand, M. A. (1936). The Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Magnesium Oxide. Physics, 7(8), 297. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1745396

[6] ENGBERG, C. J., & ZEHMS, E. H. (1959). Thermal Expansion of Al2O3, BeO, MgO, B4C, SiC, and TiC Above 1000??C. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 42(6), 300–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1959.tb12958.x

[7] Ronchi, C., & Sheindlin, M. (2001). Melting point of MgO. Journal of Applied Physics, 90(7), 3325–3331. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1398069