Rep:Fp1615 Thermal Expansion Of MgO

3rd Year MgO Computational Laboratory - session 4 beginning 27th November 2017 - Francesca Pinto

Abstract

The aim of this investigation was to use the software GULP to determine computationally the Hemholtz free energy and the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient of MgO and gain an understanding of the thermal expansion of its crystal structure. In particular, the values computed using the quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics were compared to experimental data found in literature to assess the limitations of these simulations: the obtained values are αV= 2.85 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic approximation and αV= 3.07 x 10-5 K-1 for the simulations based on the molecular dynamics model, which respectively differ from the literature value by 30.3 % and 24.9%. The quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics model was found to break down at high temperatures due to anharmonicity effects, whereas molecular dynamics simulations are not accurate at low temperatures, at which quantum effects are significant, but can be used to investigate a variety of phenomena at high temperatures such as phase transitions.

Introduction

Vibrations in Crystals

Vibrations in solids play a major role in many of their physical properties ranging from phase transitions, free energy, thermal expansion and heat capacity to thermal conductivity and superconductivity; molecular dynamics (MD) and lattice dynamics (LD) are two complementary approaches that are often use to investigate such properties in crystal structures.[1][2] Crystalline solids are distinguished from other states of matter by a periodic arrangement of the atoms, but the image of a fixed and rigid array of ions is only an approximation of the actual ionic configuration as it fails to explain a wide range of equilibrium and transport properties and the interaction of various types of radiation with the solid.[3] A crystal is a dynamic structure in which each ion oscillates about its position in the lattice, which is thus its mean equilibrium position and not its fixed instantaneous position, with an amplitude that can be of the order of 10% of an interatomic distance.[2][3][4] These fluctuations arise from thermal energy in the lattice and are therefore more pronounced at higher temperatures. However, according to quantum theory, the static model is incorrect also at 0 K because of the uncertainty principle that requires localised ions to possess momentum at any temperature.[3]

The movement of one atom in its site causes the neighbouring ions bound together by electrostatic attraction to respond resulting in the spreading of a collective motion through the crystal.[5] The overall collective vibrational motion of the lattice is a superposition of many modes of vibration. Lattice vibrations can be interpreted as both travelling waves and phonons, which are quanta of lattice vibrations analogous to a photon representing a quantum of electromagnetic radiation. Each wave is characterised by its wavelength λ, frequency ω and direction of travel. In addition, each mode can be thought of as a phonon with energy given by the equation:

(1)

Note that each mode will also have the zero point energy associated with it.

Because of the fact that wavelength values range in scale from interatomic distance to infinity, it is more convenient to define a wavevector k as the vector parallel to the direction of propagation of the wave:[2][6]

(2)

It is therefore necessary to think in terms of the reciprocal space, also defined as the k-space, rather than real space. There is an energy level for each value of k and the allowed values of k are equally spaced in the k-space.[7] If the interatomic spacing is defined as a, the unique values of k can only be found in the interval -π/a < k < π/a, which corresponds to the First Brillouin Zone (FBZ).[7] The repeat period is therefore equal to 2π/a, which is the interatomic distance a* in reciprocal space.[7] The fact that a*=2π/a indicates that a larger cell in real space corresponds to smaller cell in reciprocal space.

In lattice dynamics the relationship between k and ω is called phonon dispersion. Because of the periodic nature of crystals, phonon dispersion can be fully described by considering the behaviour of phonons within the FBZ.[8]For a one-dimensional chain of diatomic molecules formed by ions of mass m1 and m2 with internuclear separation a, the dispersion curve is given by the following expression:[9]

- (3)[9]

The two solutions of this one-dimensional model illustrate the existence of two vibrational modes per each wavevector which are the optical and acoustic, in which atoms move out-of-phase and coherently respectively. The multiplicity of the branches is therefore a consequence of having a diatomic unit and thus an increased number of different atoms associated per each lattice point: this is caused by the doubling of the repeat period in real space, which results in the Brillouin zone to be half as long (the branches can be thought of as folding back as many times as the repeat period is increased).[7] These considerations can be extended to the three-dimensional lattice, in which p ions associated with each lattice point present 3 acoustic modes and 3(p-1) optical modes (e.g. MgO will display 6 branches in total).[10] In the reciprocal space, the Brillouin zone becomes a three-dimensional volume with wavevectors kx, ky and kz. As it is not possible to illustrate phonon modes for all k values, they are usually plotted along certain lines in the Brillouin zone (e.g. Γ=(0,0,0)).[7]

As a consequence of the fact that the atoms are arranged as an infinite periodic lattice, there is a very large number of vibrational modes and branches instead of single levels are observed in the phonon dispersion graph. The Density of State DOS(ω)dω is defined as the number of modes with angular frequency ω between ω and ω+dω and represents a return from reciprocal space to real space.[2][7] In order to generate the DOS curve it is necessary to sum over all modes and wavevectors, which can be done by generating a list of frequency values for a grid of wavevectors: the finer the grid, the more vibrations are sampled and thus the more features appear in the DOS plot. The number of samples on which the average will be performed to generate the density of states is given by the shrinking factor N, which determines the number of uniformly spaced grid points.[7][6]

The Helmholtz free energy F(V,T) depends solely on the frequency of the modes of vibration and not directly on the wave vector and can be computed as a sum over the vibrational modes of the infinite crystal, which is approximated by a sum over a finite grid of k-points.

Quasi-Harmonic Lattice Dynamics

The potential energy between atoms of a diatomic molecule can be written as a Taylor expansion around a minimum at r0 (equilibrium geometry):

(4)[2]

(Note that in the above expression the linear term vanishes because r0 is an equilibrium geometry)

The key approximation in the theory of lattice dynamics is the harmonic approximation, which consists of neglecting all the terms of power higher than two in equation (#): due to its simplicity and predictive power, it can be successfully applied to the study of spectroscopic and some thermodynamic properties of materials.[11][2] Furthermore, it provides the link between vibrational frequencies, wave vector and interatomic forces and it is easily adapted to incorporate quantum mechanics.[2]

The majority of the main deficiencies of this model, such as the absence of thermal expansion, the infinite thermal conductivity and the temperature independence of elastic constants and bulk modulus, can be easily corrected by the quasi-harmonic approximation.[11] The two approximations differ in the choice of reference structure: in fact, the one for harmonic lattice dynamics is the minimum potential energy, whereas for the quasi-harmonic approximation the minimum free energy is used (thermodynamic equilibrium).[12]In this approximation, which was used in this investigation to simulate the thermal expansion of MgO and compute its free energy, the Helmholtz free energy of a crystal is written retaining the harmonic expression with the addition of an explicit dependence of vibration phonon frequencies on volume:

(5)[11]

In the above equation U0(V) is the zero temperature internal energy of the crystal without any vibrational contribution and E0ZP(V) is the zero point energy of the system, which is defined by the following equation:

(6)

Although lattice dynamics calculations are a very powerful tool that allows to predict vibrational frequencies and thermodynamic properties of crystalline solids over a wide temperature range, this model breaks down at high temperatures because, even if it allows the equilibrium bond length to vary with volume, it does not take into account bond breaking. Furthermore, as the temperature approaches the melting point of MgO (~3100 K at 0 GPa)[13], the phonon modes do not represent well the actual motion of the ions as the approximation overestimates the separation of vibrational levels so the computed frequency is higher than the experimental. The extreme example of anharmonicity is the melting phase transition, about which quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics theory is practically unable to give quantitative information and ceases to be able to model the motion of the atoms. In fact at the melting point, the atoms that constituted the crystalline solid start to behave like liquids and cease to vibrate with the regular periodic motion described by lattice dynamics.

Molecular Dynamics

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computer simulation that provides a method for studying crystals at high temperatures, taking full account of anharmonic interactions.[2] In MD the average physical properties and structural parameters of a system are simulated by using Newton's classical equations of motion for a set of fictitious atoms, which are assumed to interact via a model interatomic anharmonic potential, as a function of time.[14][15] This method generates the classical trajectories of a collection of a constant number of atoms, which are placed in a simulation box characterised by periodic boundary conditions and are free to move because they are no longer confined to their lattice sites. The dynamic properties are calculated iteratively as the system evolves using an algorithm to generate the atomic positions and velocities at a given time step from the positions and velocities of the previous time steps.[13] In order to compute properties as time averages of the behaviour of atoms, the following steps are performed on an initial fixed number of atoms placed at their crystallography determined sites and randomly moving at different velocities according to the Boltzmann distribution:

- Compute the forces on the atoms (F)

- Compute the accelerations

- Update the velocities:

- Update the positions of the atoms:

- Calculate the average E and T of the configuration and go back to step 1.

- At the end of the cycles measure properties of interest.

This simulation allows greater flexibility than the quasi-harmonic approximation and it is more practical to use at high temperatures, where anharmonicity is important and quantum effects are small. In fact, it is possible to calculate the properties of solids at temperatures higher than their melting points and to investigate not only equilibrium properties, but also time-dependent phenomena such as transport properties and first-order phase transitions.[14] However, this method does not allow to compute accurate values for temperatures lower than approximately 700 K and is thus expected to deviate from the values computed using quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics simulations because of the neglect of higher order quantum corrections.[14][15] Furthermore, the molecular dynamics simulation does not work at 0 K because the kinetic energy of the atoms of the ensemble is zero and it is not possible to generate the initial configuration.

Thermal Expansion of Crystalline Solids

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change in shape and volume in response to a change in temperature which is attributed to the anharmonic nature of the inter-molecular forces in solids and thus to the presence of anharmonicty in atomic vibrations.[1] In fact, the bond length of a diatomic molecule with an exact harmonic potential would not increase with temperature. According to the harmonic approximation, atoms vibrate about their equilibrium position within a perfectly symmetric well of interatomic interaction, thus populating higher energy states does not affect the equilibrium bond length.[16]

The quasi-harmonic approximation used in this investigation breaks the symmetry of the harmonic potential well, therefore increasing the temperature causes a change in the equilibrium bond length and results in thermal expansion. The equilibium volume V(T) at a given fixed temperature T is calculated by minimising equation (5) with respect to V.[11] Computing the simulated volume of the conventional unit cell at different temperatures allows to calculate the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient αv through the equation:

- (7)[17]

For cubic crystals (such as MgO), which are isotropic materials characterized by three mutually orthogonal directions, the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient αV can be calculated from the linear thermal expansion coefficient αL:

- (8)[11]

Method

The physical properties of MgO crystals were investigated by running computational simulations using the General Utility Lattice Program (GULP) accessed via the DLVisualize graphical user interface in the Linux RedHat environment.

The structure of MgO is defined as a crystal lattice and its conventional cell, which is chosen because of its convenient relationship with lattice symmetry, is a face-centered cubic lattice with a Mg[0,0,0] and O[1/2,1/2,1/2] motif that consists of equal numbers of magnesium and oxygen ions placed at alternate points of a simple cubic lattice in such a way that each ion has six of the other kind of ions as its nearest neighbours (octahedral coordination).[3]

Both the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation and the Molecular Dynamics simulations were run by using a simple force field for MgO, in which a repulsive Buckingham potential operates between the Mg2+ and O2- ions. The short-range Buckingham potential used was derived empirically by fitting to the experimentally measured lattice properties of a series of binary metal oxides. [18]

Quasi-Harmonic Lattice Dynamics of MgO

The lattice parameters used to run the quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics simulations for the MgO lattice were the following:

| Unit Cell Type: Primitive Cell |

| Lattice Type: Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) |

Cell Vectors / Å:

0.0000 2.10597 2.10597

2.10597 0.0000 2.10597

2.10597 2.10597 0.0000

|

Cell Parameters:

a = 2.9783 Å alpha = 60.0000 degrees

b = 2.9783 Å beta = 60.0000 degrees

c = 2.9783 Å gamma = 60.0000 degrees

|

The Phonon Dispersion

The phonons modes were computed at 50 points along the conventional path in k-space, which includes the special points W-L-G-W-X-K, and displayed as a phonon dispersion plot that allows to visualise the variation of the frequencies over the full three-dimensional k-space. As predicted in the introduction, the plot presents six branches (3 acoustic that pass through Γ and 3 optical). The simulated plot shown in Figure 3 can be verified experimentally by X-ray thermal diffuse scattering.[19]

The Phonon Density of States

These summation of all the states (labelled by their k-point) at a particular frequency calculations was carried out by increasing the shrinking factor N, which defines the NxNxN grid of k-points on which the average is performed, until a smooth DOS curve was obtained.

Figure 4 illustrates the density of states obtained by using a 1x1x1 grid, which is characterised by 4 distinct peaks at 286, 351, 676 and 800 cm-1. This DOS was only computed for a single k-point, which corresponds to the special point L as determined by inspection of the phonon dispersion in Figure 3 (the line vertical line L intersects the dispersion curves at the above mentioned frequencies). The intensities of the peaks at 286 and 351 cm-1 are double the intensities of the other two peaks indicating that they are doubly-degenerate branches. Confirming that the dispersion curve of MgO displays 6 branches as discussed in the introduction.

As shown in Figures 4-11, as the grid size increases the initially sharp peaks become a smooth curve that can be considered as a reasonable approximation for the Density of States. In particular, it can be observed that a grid size of 24x24x24 would be a convenient compromise between a sufficient accuracy of the computed values and computational (CPU) time. In fact, the DOS curve remains practically unvaried when the shrinking factor is further increased to 32 and 48.

Selecting the Size of k-points Grid

In order to select an appropriate size of k-points grid for the quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics simulation of the thermal expansion of MgO, the Helmholtz free energy was computed at 300 K and 0 GPa. Varying the shrinking factor N allowed to establish empirically the best compromise between accuracy and CPU time by observing when the value of F converged to 6 dp to the infinite grid value.

Table 1. Helmholtz Free Energy computed as a sum over finite grids of k-points of different sizes NxNxN.

| Grid Size | Helmholtz Free Energy /eV | Difference in Helmholtz Free Energy

Compared to Converged Value /meV |

|---|---|---|

| 1x1x1 | -40.930301 | -3.818 |

| 2x2x2 | -40.926609 | -0.126 |

| 3x3x3 | -40.926432 | 0.051 |

| 4x4x4 | -40.92645 | 0.033 |

| 6x6x6 | -40.926471 | 0.005 |

| 8x8x8 | -40.926478 | 0.003 |

| 10x10x10 | -40.926480 | 0.003 |

| 12x12x12 | -40.926481 | 0.002 |

| 16x16x16 | -40.926482 | 0.001 |

| 18x18x18 | -40.926483 | 0 |

| 20x20x20 | -40.926483 | 0 |

| 32x32x32 | -40.926483 | 0 |

Differences between the free energy values computed using increasing grid size and the converged free energy value show that a 2x2x2 grid is appropriate for calculations accurate to 1 meV and 0.5 meV and a 3x3x3 grid size can be used for calculations accurate to 0.1 meV.

The 18x18x18 grid was selected to compute the thermal expansion coefficient of MgO as N=18 is the smallest shrinking factor for which the Helmholtz free energy converged to 6 dp to its infinite grid value. The grid size should be determined individually for each crystal structure as it depends on the dimension of its reciprocal space and thus of the FBZ. It would be safe to assume that a similar grid could be appropriate to carry out these calculations on CaO, a metal oxide that is a Face-Centred Cubic lattice (FCC) as MgO. The lattice parameter of CaO is 3.393 Å and is thus similar to the lattice parameter of MgO meaning that they will also have a small difference in the periodic repeat unit in reciprocal space.[18] On the other hand, a microporous Zeolite structure such as Faujasite, which has a much bigger lattice parameter (24.66 Å) and belongs to the hexoctahedral crystal class, would probably require a grid with a smaller shrinking factor N because the periodic repeat unit in k-space is much smaller.[20] A reasonably accurate DOS curve could be computed with fewer k-points: due to the "folding" of the FBZ a single k-point would sample more frequencies in Faujasite than in MgO. Conversely, a much larger shrinking factor would be necessary to compute the DOS curve for metals (e.g. lithium), which are characterised by a much smaller lattice parameter. In fact, the FBZ in a metal would span a much larger range, requiring a denser grid of k-points.

The Thermal Expansion

According to equation (7), in order to calculate the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient αV the volume of the primitive MgO cell was computed between 0 K and 3000 K every 50 K at a constant pressure of 0 GPa. The shrinking factor used for the k-space sampling was 18 as determined in the previous section.

Molecular Dynamics of MgO

The software GULP was used to carry out the Molecular Dynamics simulations using a supercell containing 32 MgO units. In order to investigate the thermal expansion of MgO, the following parameters were used to calculate the average volume of the supercell at temperatures between 50 K and 3000 K, increasing by 50 K steps and keeping pressure constant at 0 GPa:

| Ensemble: NPT - constant number of particles (N), Pressure (P) and Temperature (T) |

| Time Step = 1.0 fs |

| Number of Equilibration Steps = 500 |

| Number of Production Steps = 500 |

| Number of Sampling Steps = 5 |

| Number of Trajectory Write Steps = 5 |

In this investigation a supercell was used to allow more flexibility when system is vibrating. It would not be possible to carry out this simulation using a primitive cell containing a single MgO unit as it was done for the QHLD because it would be equivalent to sampling the phonons at k=(0,0,0) only, point in the k-space at which every cell of the system moves exactly in phase. This method could be improved by using a larger supercell whose size can be determined in an analogous way to the selection of the grid size for the QHLD simulations: the cell size could in fact be varied until the output values of interest converge to a suitable number of decimal places, which would have to be selected to allow to calculate accurate values in a reasonable CPU time.

Results and Discussion

The Helmholtz Free Energy of MgO (Quasi-Harmonic Lattice Dynamics)

As shown in Figure 14, the computed Helmholtz free energy becomes more negative as temperature and the simulated volume of the conventional cell increases. This is in agreement with the definition of Helmholtz free energy, which can be expressed as follows:

(9)[17]

In fact, as the temperature increases the volume of the primitive MgO cell expands and entropy increases. The second term of the above equation thus becomes increasingly predominant and results in the free energy to become more negative. The value of free energy at 0 K is different than zero and is equal to the zero point energy of the system as explained in equation (5).

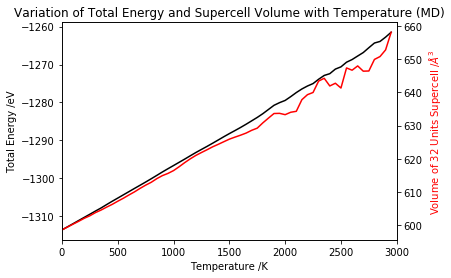

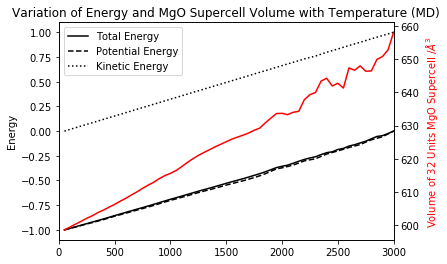

The Energy of MgO (Molecular Dynamics)

The algorithm used in molecular dynamics model minimises the total energy of the MgO supercell in order to compute the average volume at certain temperature and pressure conditions. As shown in Figures 15 and 16, as temperature increases the kinetic energy becomes more positive reflecting the motion of the atoms that becomes increasingly faster. At the same time, the distance dependent potential energy becomes less negative as atoms are free to move and get further apart. The overall result is a the total energy becoming more positive as the supercell expands as a result of thermal motion.

The Thermal Expansion of MgO

As shown in Figures 17-20, the Density of States curve computed using a 18x18x18 grid changes significantly with temperature: in fact, it can be observed that the maximum shifts to lower frequencies as temperature is increased. As mentioned in the introduction, in the quasi-harmonic approximation there is an explicit dependence of vibration phonon frequencies on volume. This feature is indeed a direct effect of anharmonicity and thermal expansion and is consistent with the observation of closer energy levels at high energies, which are increasingly populated at higher temperatures.[16] The DOS curve not only shifts to the left, but also contracts: this observed change may be interpreted as a result of the increase in volume of the cell being analyzed, which causes a contraction in the reciprocal k-space from which the Density of States is directly mapped.

Figure 21 illustrates the results of the simulations that were carried out using quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics (QHLD) and molecular dynamics (MD) in order to investigate the thermal expansion of MgO and compute its volumetric thermal expansion coefficient αV according to equation (7). A convenient way of assessing the accuracy of the methods used is to compare the two sets of results obtained and account for the differences between the two, which must be due to their implicit approximations.[12] For temperature values approximately ranging from 500 K to 1200 K, the differences in the computed volumes of MD and QHLD are very small indicating that in this region both approximations are valid.[12]

For temperatures higher than 1200 K, the values of the volume of the conventional cell computed using MD and QHLD start to diverge because the anharmonic terms that have been excluded from the quasi-harmonic approximation become significant and the model breaks down: when the temperature approaches the melting point the volume starts to increase exponentially with respect to temperature as high energy states keep getting more populated until the optimisation of the free energy fails (in this investigation, it was attempted to use QHLD to compute the volume at 3000 K, but the free energy failed to converge).

The molecular dynamics computed data is linearly proportional to the temperature throughout the range of interest. The oscillations in simulated volume observed at T > 2000 K are most probably due to the use of calculation parameters that are not appropriate for the conditions being examined. Due to time constrains, it was not possible to carry out these simulations with different parameters, but it would be highly suggested to vary the timestep and the number of sampling and equilibration steps in order to determine the optimum input for these calculations.

On the other hand, at lower temperatures T < 500 K the time-steps algorithms that are used to model the continuous equations of motion do not allow to compute accurate values and the simulated volume decreases too sharply with decreasing temperature when compared to experimental data.[15] This is due to the neglect of quantum effects such as the fact that the system possesses a zero point energy. Furthermore, according to statistical thermodynamics at low temperatures only the vibrational ground state is accessible and therefore there is little variation in the volume of the crystal structure, which is in this temperature range mainly dependent on zero point energy as confirmed by the QHLD data that "flattens" as T → 0 K.

In order to further understand the approximations used in this investigation, the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion αV was compared to experimental results found in literature. Even though it would have been more accurate to perform a linear fit for T > 500 K, data points at lower temperatures were considered because it is only possible to compare data within the same range. In particular, αV was calculated for temperatures in the range 300 K < T < 1050 K to compare the simulated values to the experimental value αV=4.09 x 10-5 K-1 obtained by J. Zhang[21] using an energy-dispersive x-ray method at 0 GPa in the range 300 K < T < 1073 K (1050 K was chosen as it was the closest computed value to 1073 K).

Figures 22 and 23 show the linear fit on the QHLD and MD data respectively, whose slope was used, according to equation (7), to calculate the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient of MgO over the above indicated range of temperature. The obtained values are αV= 2.85 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic approximation and αV= 3.07 x 10-5 K-1 for the simulations based on the molecular dynamics model, which respectively differ from the literature value by 30.3 % and 24.9% and are thus reasonably close to the experimental value obtained by J. Zhang and also in agreement with previous results of Suzuki in the same temperature range at zero pressure.[21] [22]

Figures 24 and 25 illustrate the residual plots of the linear fits performed: although they indicate a good fit for the MD data (no clear trend in residuals), a clear trend in the residuals plot for the QHLD data demonstrates that the plot is non-linear. The expansion coefficient calculated using the MD model was closer to the experimental data and this can be due to the poor fitting of the quasi-harmonic approximation data points. In order to check whether excluding the lowest temperatures from the range of the fit for QHLD could improve the quality of the fit, the volumetric expansion coefficient αV was calculated for the temperature range 700 K < T < 1200 K.

The obtained values are αV= 3.16 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic approximation and αV= 3.15 x 10-5 K-1 for the simulations based on the molecular dynamics mode. The values computed for this temperature range are almost equal for the two approximations confirming that in this range the simulations values are accurate because two models, which are based on different approximations and use different methods, yield the same results.

However, in Figure 29 the residual plots still suggests that a linear fit is not the optimal choice for the QHLD data. In order to overcome this problem, it is possible to compute the temperature derivative at each temperature tested in the simulation according to equation (7) in order to compute numerically the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient and compare it to literature.[11]

Figure 30 shows that the volumetric thermal expansion coefficients computed using the quasi-harmonic approximation have values in approximately the same range only in the central region of the range of temperatures being analysed, while the coefficients calculated using molecular dynamics remain more or less constant fluctuating around the same value at all temperatures.

Figure 31 illustrates how the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient of MgO compare with experimental literature data at different temperatures and zero pressure.[22][23][24] Although the performed simulations underestimate the value of the volumetric thermal expansion coefficient, the shape of the curve of αV over the temperature range 300 K < T < 1250 K are in agreement with the ones reported in literature. It is interesting to point out that the molecular dynamics simulation performed by M. Matsui[14] by incorporating quantum corrections in the model yields values that are significantly closer to experimental values. This demonstrates how a deep understanding of a model and its limitations is crucial to improve its approximations in order to better match experimental data.

Conclusion

In this experiment quasi-harmonic lattice dynamics and molecular dynamics simulations were used to investigate the thermal expansion of a MgO crystal structure. The obtained values are αV= 2.85 x 10-5 K-1 for the quasi-harmonic approximation and αV= 3.07 x 10-5 K-1 for the simulations based on the molecular dynamics model, which respectively differ from the literature value by 30.3 % and 24.9%. Furthermore, volumetric thermal expansion coefficients were computed at each of the temperatures at which the volume expansion was simulated displaying a similar trend to the experimental data found in literature. The quasi-harmonic approximation was found to break down at high temperatures due to the increasing significance of anharmonicity as the melting point is approached; on the other hand, the molecular dynamics method was found to be useful in calculating properties of solids up and above melting points, provided the right choice of input parameters for the calculations. The fact that such different models and methods yield very similar volume values from approximately 500 K to 1200 K demonstrates that the approximations used are effective and can be used to describe and simulate experimental properties. Although these simulations are limited by the accuracy of the potential being used and by the need to use a mathematical representation of the actual potential (e.g. restriction to rigid ion model), these calculations in conjunction with experiments and theoretical calculations can provide many useful insights that cannot be obtained by any other method.[6]

Further Work

The simulations carried out in this investigation could be repeated by varying the pressure to assess how it affects lattice dynamics. Furthermore, molecular dynamics calculations could be extended to temperatures > 3000 K to better understand the phase transition of MgO. In order to do this however, it would be necessary to carefully determine the most appropriate parameters for the calculations, as in this experiment it the ones selected caused unexpected fluctuations at temperatures higher than 2000 K. In conclusion, these simulations can also be applied to other crystal structures of different compositions and size by adjusting the input parameters.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 R. Righini, Physica B C, 1985, 131, 234–248.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 M. Dove, École thématique de la Société Française de la Neutronique, 2011, 12, 123–159.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 N. W. Ashcroft and N. D. Mermin, Solid State Physics, Saunders College, Philadelphia, 1976.

- ↑ M. Born and K. Huang, Dynamical theory of crystal lattices, Oxford Univ. Press, London, 1956, p 1-3.

- ↑ R. J. Bosco Balaguru and B. G. Jeyaprakash, Lattice Vibrations, Phonons, Specific Heat Capacity, Thermal Conductivity, School of Electrical and Electronics Engineering (SASTRA University), pp 1-9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 M. T. Dove, Introduction to lattice dynamics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 R. Hoffmann, Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English, 1987, 26, 846–878.

- ↑ G. D. Price, S. C. Parker and M. Leslie, Physics and Chemistry of Minerals, 1987, 15, 181–190.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 P. K. Misra, Physics of condensed matter, Academic Press, Burlington, 2012, p 44.

- ↑ J. A. Gonzalo, Frutos Jose ́de. and J. García, Solid state spectroscopies: basic principles and applications, World Scientific, River Edge, 2002, pp 79-80.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 A. Erba, M. Shahrokhi, R. Moradian and R. Dovesi, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 2015, 142, 044114.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 R. G. D. Valle, E. Venuti and A. Brillante, Chemical Physics, 1996, 202, 231–241.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 L. Vočadlo and G. D. Price, Physics and Chemistry of Minerals, 1996, 23, 42–49.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 M. Matsui, G. D. Price and A. Patel, Geophysical Research Letters, 1994, 21, 1659–1662.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 M. Matsui, The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1989, 91, 489–494.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 J. P. Srivasatava, Elements of Solid State Physics, PHI Learning Private Limited, Delhi, 4th edn., 2014, pp 151-155.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 P. W. Atkins and J. D. Paula, Atkins Physical Chemistry, University Press, Oxford, 8th edn., 2006, pp 60-61 and p 96.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 T. S. Bush, J. D. Gale, C. R. A. Catlow and P. D. Battle, Journal of Materials Chemistry, 1994, 4, 831.

- ↑ R. Xu and T. C. Chiang, Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 2005, 220.

- ↑ D. N. Stamires, Clays and Clay Minerals, 1973, 21, 379–389.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 J. Zhang, Physics and Chemistry of Minerals, 2000, 27, 145–148.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 I. Suzuki, Journal of Physics of the Earth, 1975, 23, 145–159.

- ↑ G. K. White and O. L. Anderson, Journal of Applied Physics, 1966, 37, 430–432.

- ↑ S. Ammiraju, R. Madhusudhan, K. Narender, K. G. K. Rao and N. G. Krishna, High Temperature, 2014, 52, 640–653.