Rep:CfarnhamTransitionStructures

by Charlie Farnham

Transition States and Reactivity: Introduction

Gaussian is a computational chemistry program originally invented by the theoretical chemist John Pople in 1970.[1] The program efficiently calculates reaction coordinates across potential energy surfaces and by taking advantage of Gaussian orbitals can determine transition state structures. Gaussian type orbitals are functions that substitute for atomic orbitals when determining molecular orbitals in a reaction, this substitution speeds up calculations significantly.[2]

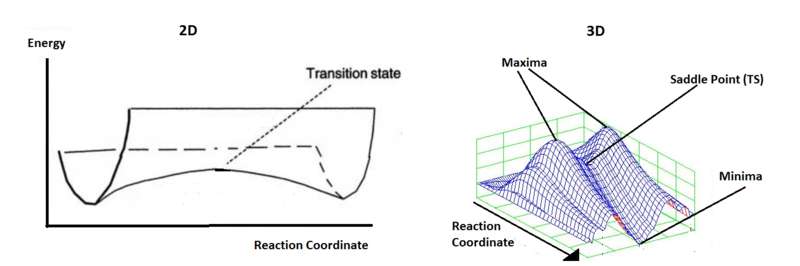

Potential Energy Surfaces

Potential energy surfaces are a 3-dimensional plot of potential energy, possessing many maxima, minima and stationary points. Locating a desired reaction coordinate between the two minima representing reactant and product geometry is difficult, due to the multitude of alternate, thermodynamically-favourable pathways available. Hence, prior knowledge of approach trajectories and transition state structure is required. A local minimum on a potential energy surface corresponds to a low-energy geometry (when compared to neighboring points) that occurs at equilibrium. If this minimum is the lowest energy point across the entire potential energy surface, it is called the global minimum (the same principle applies to maxima). The gradient at a minimum equals zero and the second derivative, corresponding to the force constant, would result in a positive value in all dimensions. A transition state corresponds to a first order saddle point on the potential energy surface.[3] In this case, the gradient also equals zero and the second derivative would provide a positive value in all dimensions except that corresponding to the reaction coordinate. Along the reaction coordinate from minimum to minimum, the transition state is, in fact, a maximum and so gives a negative force constant value. A frequency calculation provides the vibrational frequencies for a structure. Unlike for products and reactants, an imaginary frequency is expected for transition states. This is because the single vibrational mode that corresponds to the reaction coordinate involves a slope down in potential energy.

(These points are called second order saddle points, not maxima. You are still minimised in all other coordinates and I would suspect there is no real maximum of a PES except at the limits of the coordinates where the atoms are on top of each other Tam10 (talk) 10:41, 8 February 2017 (UTC))

Nf710 (talk) 13:59, 10 February 2017 (UTC) Your definition of a a TS is correct but you have said a PES is 3 dimensional actually this is incorrect as the dimensions are the number of degrees of freedom which are the normal modes.

Methods

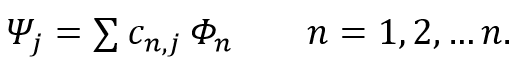

Molecular orbitals are approximated using the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) method. The atomic orbitals involved are called the basis set, which consists of a group of wave functions, that when combined describe the electron distribution in the entire molecule.

Slater functions provide an almost ideal representation of atomic wave functions, but because of their accuracy require a lot of time when used in multi-nuclear and electron calculations. Instead, a linear combination of Gaussian functions are used to replace each Slater function, speeding up the calculations. The reason for this is that the product of two Gaussian functions on two centres is equivalent to a Gaussian on a third centre between the two.[4]

It is time consuming to evaluate many integrals. Instead, the semi-empirical PM6 method utilises a pre-determined catalogue of values for frequently occurring integrals, speeding up the process but providing a less accurate representation of wave functions. The B3YLP method with the 6-31G(d) basis set is more precise, but at the cost of being more time consuming as the Hatree-Fock method evaluates every integral for the entire molecule.

Nf710 (talk) 14:04, 10 February 2017 (UTC) Good understanding , almost right. B3LYP is a DFT calculation which uses a HF calculation to calculate the exchange correlation contributions to the energy.

Aims

in this investigation, reaction coordinates and transition states for various pericyclic reactions will be modeled, characterized and analysed using the Gaussian software. The semi-empirical PM6 method will be utilized to approximate quickly initial geometries. Where necessary, the more time-demanding DFT (B3LYP) (density functional theory) method with the basis set 6-31G(d) will subsequently optimise these structures further. IRC (intrinsic reaction coordinate) calculations will be used to confirm and illustrate that the desired reaction is indeed simulated, occurring via the correct first order saddle point and ending at the desired minimum. The more steps that the IRC is calculated with, the more accurate it will be, but at the cost of taking more time. Comparisons will be drawn between the formation of endo- and exo- Diels Alder adducts, by considering reaction symmetry and orbital interactions. Alternative pathways will also be explored, including chelotropic reactions and less favoured regioselectivity, with particular focus on sterics and secondary orbital interactions.

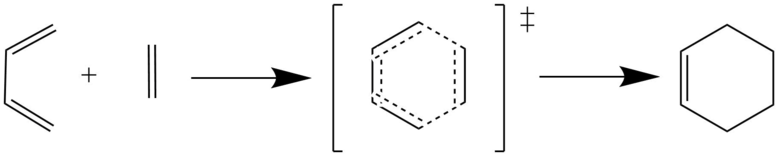

Exercise 1: Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

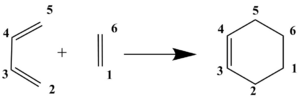

The first reaction simulated in Gaussian was the concerted, Diels Alder [4+2] cycloaddition seen below. Cyclohexene was produced from butadiene and ethylene. Both reactants and the transition state were optimised at the PM6 level. Frequency calculations confirmed the correct structures were obtained, with the transition state being the only structure with an imaginary frequency. Subsequently, an IRC was run to allow the product cyclohexene to be found and then optimised at the PM6 level.

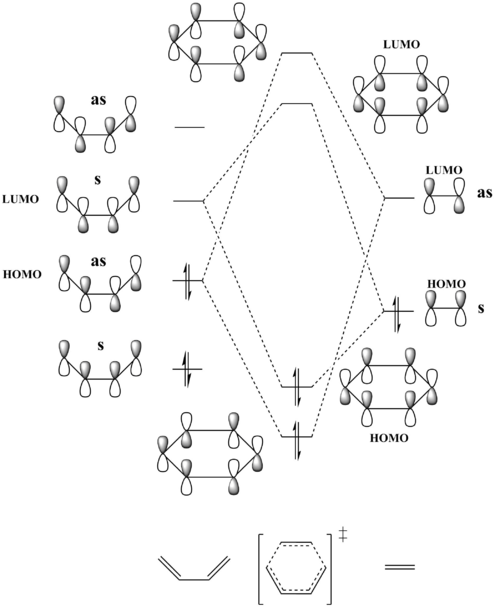

Molecular Orbital Analysis

The following MO diagram depicts the formation of the four MOs of the cyclohexene transition state from the HOMOs and LUMOs of butadiene and ethene. Though not shown on the diagram, it should be noted that the total energy of the TS orbitals will be higher than that of the reactants, as the TS is at the maximum in terms of energy on the reaction coordinate.

The MO diagram above correlates to the jmol orbitals included below. A reaction is allowed when the symmetries of the orbitals involved are the same and therefore the orbital overlap is non-zero. This allows mixing of orbitals and the formation of new molecular orbitals. Conversely, a reaction is forbidden when the orbitals involved are not of the same symmetry and the orbital overlap is zero, disallowing mixing.

| Symmetry Combination | Orbital Overlap |

|---|---|

| Symmetric-Symmetric | Non-Zero |

| Symmetric-Asymmetric | Zero |

| Asymmetric-Asymmetric | Non-Zero |

The HOMO of ethene and the LUMO of butadiene are both symmetric and therefore interact to form the HOMO and LUMO of the cyclohexene transition state. The LUMO of ethene and the HOMO of butadiene are both asymmetric and mix to form the transition state HOMO-1 and LUMO+1 orbitals. Here, the electron demand is as expected and not inverse. Contributor orbitals that are closer in energy to the newly formed molecular orbitals will contribute more due to a larger orbital coefficient.

| Ethene | Butadiene | Cyclohexene Transition State | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bond Length Analysis

Hybridisation effects bond lengths, with more s character resulting in a tighter hold on bonding electrons. This means the electrons are closer to each nucleus and therefore the bond is shorter. The typical van der Waals radius of a carbon atom is 1.7 Å.

| C-C Bond Type | Typical Bond Length/ Å [5] |

|---|---|

| sp3-sp3 (single) | 1.54 |

| sp3-sp2 (single) | 1.50 |

| sp2-sp2 (double) | 1.47 |

The carbons are labelled as seen in the following diagram.

Tabulated below are the 4 C-C bond lengths belonging to the reactants and the 6 C-C bond lengths of the TS and products, with comparisons to literature. Values obtained with the Gaussian software for all lengths are in reasonable agreement with the literature. Any discrepancy is likely due to the fact that the PM6 method was used, which is semi-empirical, less accurate and used to save time. Using the B3LYP method to optimise the structures further would likely reduce any discrepancy between experimental and literature values.

| C-C Bonds | Bond Length/ Å | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactants | Reactants (lit) [6] | Transition State | Cyclohexene | Cyclohexene (lit) [7] | |

| C1-C2 | N/A | N/A | 2.1148 | 1.5399 | 1.5150 |

| C2-C3 | 1.3353 | 1.3380 | 1.3798 | 1.5003 | 1.5040 |

| C3-C4 | 1.4684 | 1.4540 | 1.4111 | 1.3375 | 1.3350 |

| C4-C5 | 1.3353 | 1.3380 | 1.3738 | 1.5003 | 1.5040 |

| C5-C6 | N/A | N/A | 2.1148 | 1.5400 | 1.5150 |

| C6-C1 | 1.3273 | 1.3305 | 1.3817 | 1.5406 | 1.5500 |

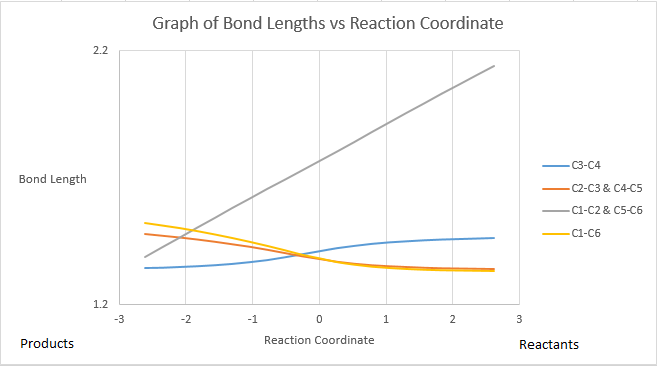

From the table above, it can be seen that the butadiene single bond (C3-C4) shortens throughout the reaction. The bond changes from single to double and the hybridisation switches from sp3 to sp2 on both carbons during the pi bond formation. The butadiene double bonds (C2-C3 and C4-C5) and the ethene double bond (C1-C6) all lengthen as they pass through the TS to the product because the pi bonds break causing the double bonds to change into single bonds. The two new single carbon bonds (C1-C2 & C5-C6) are already shorter than two van der Waals radii for a carbon atom at the transition state (2.11 Å instead of 3.40 Å). This indicates that the orbitals of the two reactants are already interacting. In the product, the bond length becomes 1.5399 Å, which is exactly the expected typical sp3 C-sp3 C length (as seen in the first table of this section).

The following graph is a clearer visualisation of the change in length of the newly formed carbon-carbon bonds (C1-C2 & C5-C6) as the reaction coordinate is traversed. Note that the reaction coordinate is reversed on the x axis, with reactants on the right and products on the left. The grey line shows clearly the approach of the two reactants and the orbitals interacting as the bond length decreases to that of a single bond.

The vibration corresponding to the reaction path at the transition state is included below, where the reactants approach and interact. This is the only imaginary frequency for the transition state structure. Recall from the introduction that 'the second derivative at a TS provides a positive value in all dimensions except that corresponding to the reaction coordinate. Along the reaction coordinate from minimum to minimum, the transition state is, in fact, a maximum and so gives a negative force constant value. A frequency calculation provides the vibrational frequencies for a structure. Unlike for products and reactants, an imaginary frequency is expected for transition states. This is because the single vibrational mode that corresponds to the reaction coordinate involves a slope down in potential energy.' Symmetry is maintained throughout this process and so the bond forming is synchronous in this case, which is expected with the concerted nature of a Diels-Alder reaction.

Finally, included below is vibration number 8. This is a counter example to demonstrate a vibration that is asynchronous and breaks symmetry (the bonds lengths are changing independent of eachother)

Nf710 (talk) 14:05, 10 February 2017 (UTC) Very nice first section, everything done well and concisely.

Exercise 2: Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

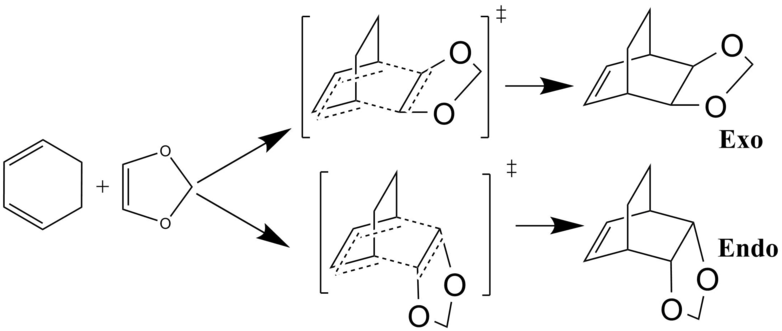

The second reaction investigated was the concerted, Diels Alder [4+2] cycloaddition of cyclohexadiene and 1,3- dioxole as depicted in the scheme below. For both the endo- and exo-products, the reactants were optimised using the PM6 method. Both transition states were located and initially optimised using the PM6 method to speed up the process. They were subsequently optimised further at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level. IRC calculations were ran to allow both products to be found and optimised. Finally, structures were confirmed using frequency calculations. Only the transition states contained an imaginary frequency.

Molecular Orbital Analysis

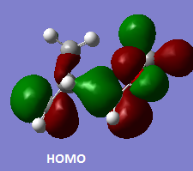

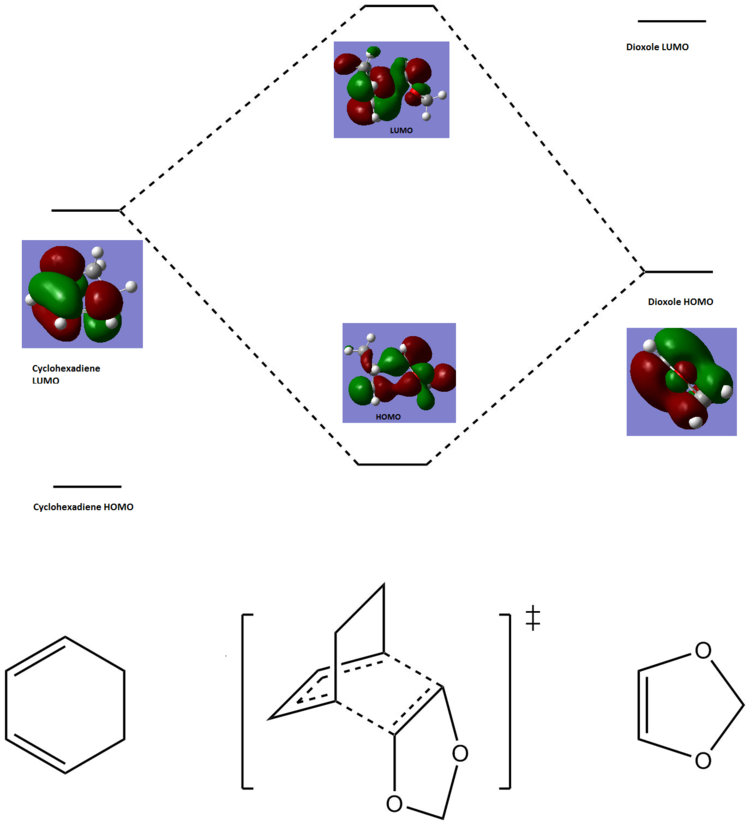

Below the jmol files for all relevant orbitals in the exo- and endo-Diels Alder reactions are tabulated. Images of all MOs have also been included to improve clarity. Reactants were optimised to the PM6 level, but both transition states were optimised to the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level in an attempt to clearly show the secondary orbital interactions.

| 1,3-Dioxole HOMO (s) | Cyclohexadiene LUMO (s) | Endo Transition State LUMO (s) & HOMO (s) | Exo Transition State LUMO (s) & HOMO (s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Below is a molecular orbital diagram, constructed using the endo-Diels Alder reaction orbitals from above. The cyclohexadiene LUMO is higher in energy than the dioxole HOMO. This is proven by the fact that the transition state HOMO receives more orbital contribution from the dioxole HOMO orbital.

The 1,3-dioxole is a high energy dienophile, due to the fact that it has electron donating oxygen atoms neighbouring the double bond. As seen from the above MO diagram, the dioxole LUMO is now too high in energy to interact with the cyclohexadine HOMO in a bonding fashion. Instead, the LUMO of the cyclohexadiene interacts with the dioxole HOMO, forming the transition state HOMO and LUMO. This is indeed the case for both exo- and endo-adducts. This reaction is therefore an example of inverse electron demand.

(All good for the formation of the HOMO and LUMO of the TSs, and you've answered the question well. What about the antisymmetric combination though? Tam10 (talk) 10:41, 8 February 2017 (UTC))

Thermodynamics

Included in this section is a table of activation energies and reaction energies for the exo and endo Diels Alder reactions of 1,3-dioxole and cyclohexadiene. All structures were optimised to the PM6 level. The reason for this is that the relative positions of energies do not change when calculating with the more accurate B3LYP/6-31G(d) level and therefore using this method has no benefit in terms of qualitative analysis.

| Reaction | Reaction Barrier/Ea (kJ/mol) | Reaction Energy/Change in Free Energy (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Exo | 166.68 | -109.42 |

| Endo | 155.57 | -96.24 |

Clearly, the endo product is the kinetic product as it has the smaller activation energy. The exo product is the thermodynamic product that would form under equilibrium conditions, because the magnitude of its reaction energy is larger and therefore the exo product is more thermodynamically stable or lower in energy.

Nf710 (talk) 14:09, 10 February 2017 (UTC) You've got the wrong answer because you didn't do it at B3LYP. b3LYP is much more accurate than PM6

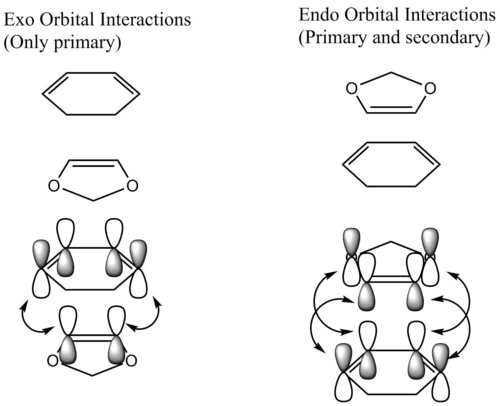

Sterics And Secondary Orbital Interactions

Below is a diagram which depicts the orbital interaction that occur throughout both the endo- and exo-transition states.

The endo transition state is stabilised by secondary orbital interactions that are not present in the exo transition state. The energy of the endo transition state and therefore activation energy of the endo reaction is lowered due to the fact that the dioxole oxygen p orbitals can interact in a secondary fashion with the back of the cyclohexadiene pi bonds. Therefore the activation energy for the exo transition state that only has primary orbital interactions is higher and if the reaction is irreversible, only the kinetic endo product would form.

The exo product does not have as severe steric hindrance as the endo product. This is most likely the reason for the exo product being more thermodynamically stable. In a reversible Diels Alder reaction, the exo product would therefore predominate.

Nf710 (talk) 14:11, 10 February 2017 (UTC) Actually if you look at the steric clashes the endo is more thermo favourable. Your explanation of the SOO is good.

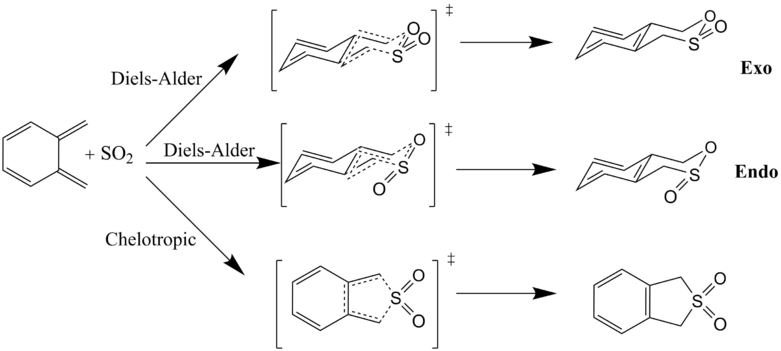

Exercise 3: Diels-Alder vs Chelotropic

The final three reactions explored in this computational investigation were the endo- and exo-Diels Alder and Chelotropic reactions of ortho-xylylene with sulphur dioxide. All products, reactants and transition states were optimised at the PM6 level. Again, IRCs were ran to simulate reaction coordinates and frequency calculation proved the presence of each structure.

(Don't use the chair conformation for these diagrams. The xylylene is planar, and its ring remains roughly planar throughout the course of the reaction. In all reactions the addition occurs on the same side of each =CH2 Tam10 (talk) 10:41, 8 February 2017 (UTC))

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate Analysis

The following .gif files of IRC calculations for the Diels-Alder and Chelotropic reactions are included to visualise each reaction paths. IRCs were run with 200 calculation steps, in an attempt to improve accuracy.

| Exo-Diels Alder IRC | Endo-Diels Alder IRC | Cheletropic IRC |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Thermodynamic Analysis and Reaction Profiles

Included below is a reaction profile diagram for both Diels-Alder reactions and the chelotropic reaction. All structures were optimised to the PM6 level. As stated before, for quantitative analysis the PM6 level is sufficient, as relative energy levels are unaffected.

(Good diagram. This style makes good use of available space and it's clear to see how each reaction compares. Try to be a bit more accurate wrt the scale (it's not uncommon to see the scale broken to help this) so it's not too misleading, and use capital J for Joules Tam10 (talk) 10:41, 8 February 2017 (UTC))

(As for the values, we asked that you use the reactants at infinite separation for consistency. You should state what you used for the reactants with words, calculation, JMol or image etc Tam10 (talk) 10:41, 8 February 2017 (UTC))

Again, the endo-Diels Alder product is the kinetically favourable one and forms in an irreversible reaction, as it has the lowest activation energy. The exo-Diels Alder has a higher barrier to reaction but is thermodynamically more stable and therefore favoured over the endo form under equilibrium conditions.

The chelotropic reaction has the highest activation energy, due to the unfavourable formation of a strained 5 membered ring. The chelotropic reaction is, however, favoured thermodynamically over even the exo adduct. This is most likely due to the enthalpic energy stabilisation gained from the second S=O double bond, which is a very strong bond.

Instability of Xylylene and Alternate, Unfavourable Diels Alder Regiochemistry

o-Xylylene is not a very stable molecule. Looking at the IRC.gif files tabulated above, it can be seen that before bond formation, the six membered ring exhibits a delocalised pi system. This pi system resembles the aromaticity present in structures such as benzene and toluene. It is the strength of this transient aromatisation that drives reactions away from the less stable xylylene reactant.

Ortho-xylylene has two diene sites that can undergo Diels-Alder reactions. Both the endo- and exo- reactions that involve the diene within the 6 membered ring as disfavoured. The reason for this is clearly demonstrated in the animation below. The reaction does not involve the formation of the stabilising, transient aromatisation of the 6 membered ring. There is therefore not a significant driving force for a Diels-Alder reaction at this alternative diene site.

Conclusion

To conclude, Gaussian is a powerful tool for simulating reaction coordinates across potential energy surfaces and locating specific structures. Transition states are easier to find with some prior knowledge of reactant approach trajectories and TS geometries. The semi-empirical PM6 method is a quick way to gain a loose approximation of desired structures, but can result in inaccuracies. To overcome this, the more accurate B3LYP/6-31G(d) method can be utilised, but the calculation time will be increased dramatically. Given more time, all structures would be optimised to the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level and all IRC calculations would be ran with a large number of steps, in an attempt to improve overall accuracy.

When considering Diels-Alder [4+2] cycloadditions, it should be noted that the endo-adduct is usually the most kinetically favourable, due to extra stabilisation from secondary orbital interactions. The exo-product is more thermodynamically favourable and will be formed under equilibrium conditions. In the case of exercise 3, there is a third, alternate reaction pathway. This is called the chelotropic reaction and is more thermodynamically stable than even the exo-Diels Alder product, but the activation barrier is the largest of all three pathways.

References

- ↑ J. A. Pople, Journal of Computational Chemistry, 2004, 25, 1-8.

- ↑ P. M. W. Gill, Advances in Quantum Chemistry, 2011, 25, 141-205.

- ↑ H. P. Hratchian and H. B. Schlegel, Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry, 2005, 10, 195-196.

- ↑ E. G. Lewars, Computational Chemistry: Introduction to the Theory And Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics, Springer, New York, 2003.

- ↑ E.V. Anslyn and D. A. Dougherty Modern Physical Organic Chemistry, Science, New York, 2006.

- ↑ C. N. Craig, P. Groner and D.C. Mckean, J Phys Chem A, 2006, 23, 7461-7469

- ↑ J. F. Chiang and S.H. Bauer, Journal ofthe American Chemical Society, 1968, 91, 1898-1891