Rep:CP2215TransitionStructureLab

Transition States Lab - Calum Patel

Introduction

Background

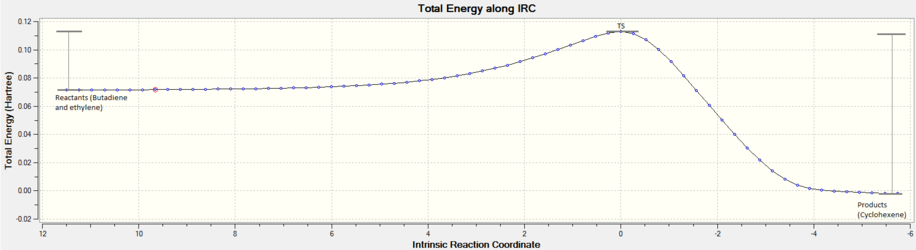

Pericyclic reactions are a cornerstone in organic chemistry and their outcomes are underpinned by both steric effects and stereoelectronic effects, as elucidated by Woodward and Hoffman in the late 1900's. [1] These effects are fundamental when predicting the transition state (TS) of which the pericyclic reaction traverses going from reactants to product. A potential energy surface (PES) represents the potential energy of a given system as a function of a changing degree of freedom in a molecule, as shown in Figure 1 where the reactants and products are represented as minima on the surface and the TS is found at the saddle point on the PES. [2] In the simple case, such as a trimolecular reaction, A + BC → AB + C, the degree of freedoms are subjectively chosen to simply be the distances between 'A' and 'B' and between 'B' and 'C'. However, complexity is encountered when many degrees of freedom are considered, such as in the case of pericyclic reactions.

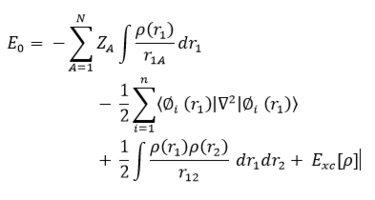

In this work, TSs of four different pericyclic reactions will be located at two different levels of theory summarized as PM6 (parameterization method 6) and B3LYP/6-31G(d), which uses density functional theory (DFT) and an orbital basis set for the atoms known as 6-31G(d). A basis set is a set of functions, known as basis vectors (Gaussian functions) that typically mimic atomic orbitals, which can be combined linearly (linear combination of atomic orbitals, LCAO) to generate molecular orbitals (MOs), as illustrated in Equation 1. This LCAO can be represented in a matrix form and is used to solve the Hamiltonian, through evaluation of the Hamiltonian integrals contained in the Hamiltonian matrix, allowing for the determination of the total energy of the respective system and of all the MO's involved. The Hamiltonian matrix is diagonalised before evaluation using either of the two methods described above.

Computational Methods

PM6 is a semi-empirical method which uses empirical data to reduce the computational cost and processing power required to solve the Hamiltonian. Reducing the number of iterations when solving the Hamiltonian matrix is necessary for larger systems, some of which will be explored in this work. [3] One disadvantage of PM6 calculations is that are limited in accuracy as they solve the Hamiltonian using empirically fitted parameters found from experimental data. [4] The B3LYP method employs a hybrid function of Hartree-Fock (HF) and DFT. DFT is an electron density operator which solves for each Hamiltonian integral within the Hamiltonian matrix, evaluating a 6-31G(d) basis set. As a consequence a much longer processing time is required for B3LYP/6-31(d) calculations. DFT is exact in principle, but in practice it requires an approximation of electron exchange and correlation terms, formally known as an exchange-correlation term (xc). [5] The underlying mathematics of the DFT is shown in Equation 2. The xc term can be calculated using a local-density approximation (LDA) or generalized gradient approximation (GGA). In this work, PM6 and B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations will be undertaken using GaussView 5.0.9. Due to having an extensive processing time, B3LYP will be used to optimise calculations that were produced using PM6, to gain results of greater accuracy. There are three different methods that may be employed in this work, using PM6 and/or B3LYP/6-31G(d) calculations and they are summarised below.

Nf710 (talk) 10:05, 17 April 2018 (BST) Great understanding of the methods here. You have clearly done some extra reading beyond the script. And it was very nice to see some equations. You could have aided this discussion even further by adding in some discussion about the pople basis sets.

Method 1 - Draw a guess TS in GaussView and run a TS(Berny) calculation using a PM6 calculation followed by an optimisation at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.The TS structure must be known prior to the calculation.

Method 2 - Draw a guess TS in GaussView and set the atoms involved in bond making at distances based on empirical data and freeze them in space. An optimisation is run at the PM6 level, the atoms are unfrozen and a TS(Berny) calculation is then run. By optimising the guess TS first GaussView is provided with a better guess structure (unlike in method 1) resulting in a more reliable TS structure after the final calculation.

Method 3 - Similar to method 2, however, rather than a guess TS an optimized product (or reactant) is used as the starting point. This structure is optimized at the PM6 level, bonds between reactant fragments are broken and atoms are frozen in space (as carried out in method 2) to provide a guess TS. This guess TS is optimized at the PM6 level before a final TS(Berny) calculation is run to provide the final optimized TS. In this method we determine a correct guess structure before attempting to find the actual TS, which is overall more reliable than methods 1 or 2.

The methods employed for each reaction studied in this work are summarized in Table 1.

| Reaction | Method | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene | 2 (PM6 only) | Good understanding of the TS |

| Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole | 2 (PM6 and B3LYP/6-31G(d)) | Good understanding of the TS |

| Diels-Alder vs Cheletropic of O-Xylylene and SO2 | 3 (PM6 only) | TS not as well defined compare to other two reactions, however, product predictions are more reliable |

| [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene Photochemical 4π Electrocyclisation | 3 (PM6 only) | TS not as well defined compare to other two reactions, however, product predictions are more reliable |

Exploring the Potential Energy Surface

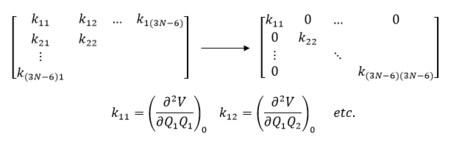

Energies obtained through employment of these methods will allow for the exploration of the PES of each molecular system studied in which there are 3Natoms-6 degrees of freedom. In this regard, the PES explored is for 3N atoms, where only the internal motions of the molecule result in a change in potential energy and not the external motions such as translations and rotations, hence the subtraction of 6. [4] . In particular, this work is primarily focused on locating stationary points on the surface (first derivatives or gradients) and then determining the curvature at these points to elucidate whether they are minima or saddle points , which is indicated by the second derivative at these points. This second derivative value is equated to the force constant, k, of the system at this point. The second derivative at each point (minima, saddle point etc.) on the PES is evaluated using a Hessian matrix and the force constants are obtained through diagonalisation of the Hessian matrix, as illustrated in figure 2, in addition to the contributions to each degree of freedom, i.e. normal modes. A minimum on the PES corresponds to reactants or products and is a point from which a small displacement in any direction increases the energy, thus the second derivative is positive. A saddle point corresponds to the TS as is located between two minima. Murrell and Laidler defined a TS as a stationary point with a single negative Hessian eigenvalue, which corresponds to a negative force constant and thus a single imaginary normal mode frequency. [2]

Reactions will explore the PES in search of the minimum energy pathway going from reactants to products. In doing so the system must traverse through the TS, the highest point of potential energy along the minimum energy pathway. In this lab, reaction pathways and more specifically minima and TS structures will be located through intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations. Energy barriers and reaction energies will be calculated using the appropriate frames from the IRC. Structures from these frames will be optimised according to the methods described above to provide energies in Hartrees (unless otherwise quoted). Reactant structures will be drawn out separately and optimised accordingly to determine energy barriers, unless otherwise stated.

Nf710 (talk) 10:08, 17 April 2018 (BST) Excellent understanding of how we use the Hessian. Well done.

Reaction of Butadiene with Ethylene

(Fv611 (talk) Great job - good work across this whole section.)

Reaction Scheme

MO diagram and Jmols

| Ethylene MO's | Butadiene MO's | Transition State Orbitals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

Cycloaddition Transition State MOs

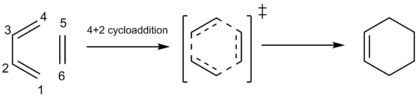

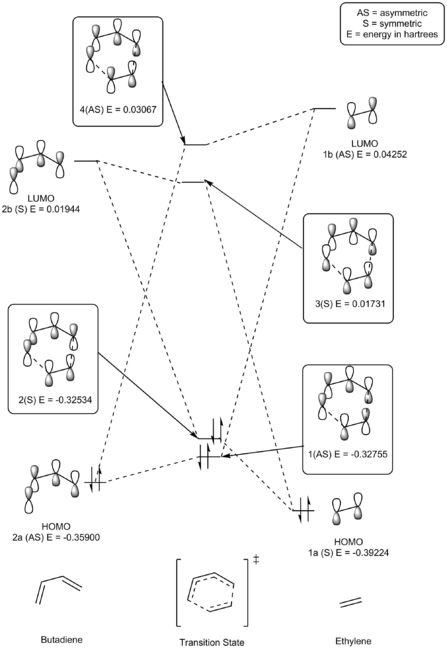

The 4 + 2 cycloaddition reaction between ethylene and butadiene (S-cis conformer) is shown in scheme 1. Reactant fragment orbitals (FO) and TS MO's can be described as being symmetric (S) or anti-symmetric (AS). As shown in Table 2 and illustrated in figure 4, only orbitals of the same symmetry can combine, either constructively or destructively. Relative energies for each MO have been presented in Hartrees and correlate to the fully optimised (PM6 level), lowest energy structures.

The S HOMO (1a) of ethylene combines constructively and destructively with the S LUMO of butadiene (2b) to form the two S TS MO's; MO 2 (HOMO) by constructive interference and MO 3 (LUMO) by destructive interference. MO 2 is closer in energy to the HOMO of ethylene (1a), indicating that MO 2 for the TS has a greater contribution from the HOMO of ethylene. The opposite is true for the TS MO 3 which is closer in energy to the LUMO of butadiene (2b) and thus has a greater orbital contribution from this FO.

The AS HOMO (2a) of butadiene combines constructively and destructively with the AS LUMO of ethylene (1b) to form the two AS TS MO's; MO 1 (HOMO-1) by constructive interference and MO 4 (LUMO+1) by destructive interference. MO 1 is closer in energy to the HOMO of butadiene (2a), indicating that MO 1 for the TS has a greater contribution from the HOMO of butadiene. The contra is true for the TS MO 4 which is closer in energy to the LUMO of ethylene (1b) and thus exhibits a greater orbital contribution from this FO.

It is clear from the MO's generated (Table 2) that only orbitals that share the same symmetry can interact to form TS MO's. In this sense, a S-AS interaction will results in zero orbital overlap whilst S-S or AS-AS interactions will result in a non-zero orbital overall, as long as the energies of the respective FOs are close enough in energy to interact.

We would expect the MOs generated for the final product to ultimately lower the energy of the whole system. Here only the energies of the TS structures are shown.

Bond Lengths and TS Vibration

From Table 3 it can be seen that as the reaction proceeds from reactants to products, the C5-C6 bond (ethylene) increases from 1.328 Å to 1.382 Å, corresponding to a change in hybridisation at these carbons from sp2 to sp3 and thus a change in bond order. This is also the case for C1-C2 and C3-C4 (sp2- sp2 double bonds in butadiene). As expected the bond length of 1.471 Å for C2-C3 is shorter then a typical single C-C bond length (1.54 Å) ,[6] this is due to C2 and C3 being both sp2 hybridised and not both sp3 hybridised. This C2-C3 bond length shortens as the reaction proceeds, decreasing from 1.471 Å to 1.411 Å in the TS and then further to 1.337 Å in the product. This value lies in parallel to a typical C=C bond length (1.33 Å) , [6] which is expected as the C2-C3 bond changes from a C-C single bond to a C=C double bond (with both carbons remaining sp2 hybridised.

In the reaction two new bond are formed between C1-C6 and C4-C5, in the TS these distances are equal at 2.115 Å, which lies as an intermediate value between a single C-C bond length and twice the Van der Waals radius of the C atom (1.7 Å). [7] These observations fit with theory, where the TS is an intermediate structure between the two reactants when bond breaking/forming occurs. From observing the IRC for this reaction, figure 5, it can be seen that the TS is closer in energy to the reactants than products indicating an early stage TS. [8] The bonds formed are both sp3 hybridised C-C single bonds of 1.537 Å, which lies in excellent agreement with literature (1.54 Å for C-C single bond). In the TS both distances (C1-C6 and C4-C5) are equal which indicates synchronous bond formation. This is further supported by the reaction path vibration in the TS (negative vibration), as shown in Figure 6 where the termini of each reactant move towards each other simultaneously.

Figure 6. Negative Vibration of TS |

LOG Files

Log file PM6 Optimisation Butadiene

Log file PM6 Optimisation Ethylene

Log file PM6 Optimisation Cyclohexene

Reaction of Cyclohexadiene and 1,3-Dioxole

Reaction Scheme and MO diagrams

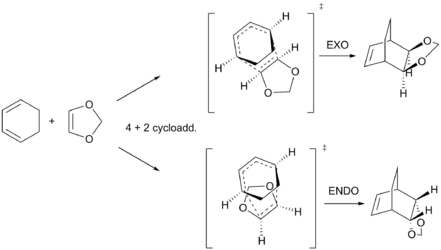

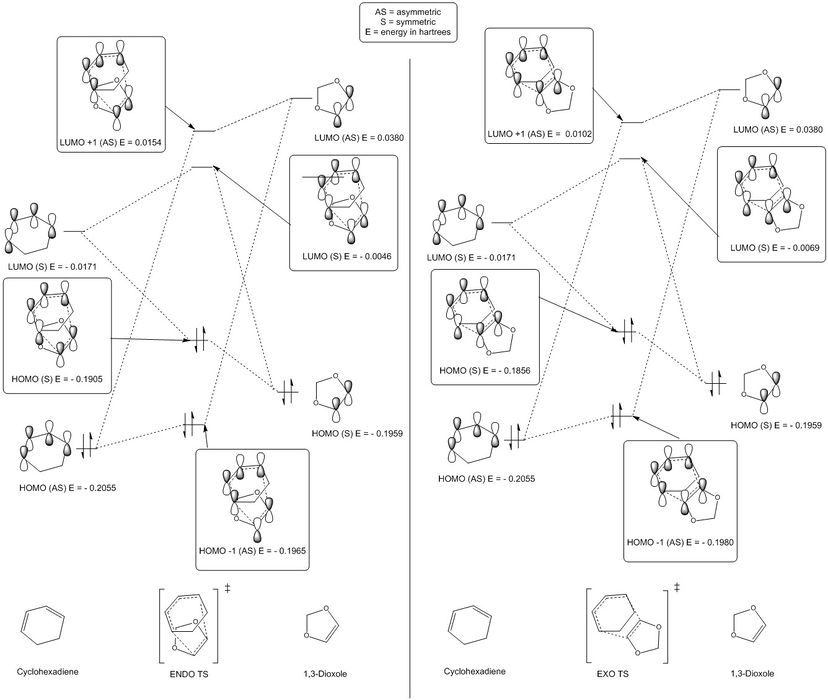

The 4 + 2 cycloaddition reaction between cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole can take one of two pathways through an ENDO or EXO TS, as shown in scheme 2, giving rise to two stereoisomer products. MO's for each reaction pathway are shown in figure 7. Note that the energies provided for the reactant molecules in figure 7 have been determined through individual optimizations of each starting reactant at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level.TS MO's for both ENDO/EXO pathways have been provided in Table 4 (corresponding MO's can be seen in figure 7). Again, the aforementioned symmetry rules have been obeyed (S-S or AS-AS = non zero overlap and AS-S = zero overlap). The energy splitting between the HOMO-LUMO TS MOs for each the ENDO and EXO case is 0.1859 Hartrees and 0.1787 Hartrees, respectively. The energy splitting between the HOMO-1 - LUMO+1 TS MOs for each the ENDO and EXO case is 0.2219 Hartrees and 0.2082 Hartrees, respectively . Interestingly, the ENDO HOMO (S) TS MOs is lower in energy than the equivalent EXO TS MO. There is marginal difference between the energies of the HOMO-1 TS MOs of each ENDO and EXO pathway. These results imply that the ENDO TS is the lower energy structure. This will be confirmed through compuational thermochemical analysis (see below).

| ENDO Transition State Orbitals | EXO Transition State Orbitals | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

Inverse Or Normal Electron Demand

Single point energy calculations have been carried out at the B3LYP/6-31G(d) level on the reactant molecules in the same frame (from the relevant IRC calculation) level to qualitatively determine the electron demand of the cycloaddition reaction. The energies of the interacting reactant MO’s differ marginally between the ENDO and EXO case; -0.1860 (ENDO) and -0.1914 (EXO) Hartrees for the filled interacting orbital and -0.0174 (ENDO) and -0.0165 (EXO) Hartrees for the unfilled interacting orbital. These energies correspond to the filled interacting orbital being the HOMO of the dienophile (1,3-Dioxole) and the unfilled interacting orbital being the LUMO of the diene (Cyclohexadiene), these MOs are shown in Table 5. Interestingly, these energies differ slightly from those determined through optimisations of the individual starting reactants (figure 7).

Nf710 (talk) 10:14, 17 April 2018 (BST) This is because there are more termins in the electron static potential part of the hamiltonian. And this is the only way you can get a fair comparison on the Energies.

| HOMO of 1,3-dioxole | LUMO of cyclohexadiene | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Normal electron demand Diels Alder (4 + 2 cycloaddition) reactions are described by the dienophile being electron deficient and diene being electron rich, thus the LUMO of the dienophile interacts with the HOMO of the diene. The opposite case is true for inverse electron demand alternative. [6]

In this reaction the HOMO of the dienophile and LUMO of the diene are closest in energy and thus the interaction is stronger than that between the LUMO of the dieneophile and the HOMO of the diene, strongly indicating that this reaction is governed by inverse-electron demand. This result is expected as electron donating group (EDG) on the dienophile (two oxygen lone pairs) typically raise the energy of the HOMO, resulting in a better energy overlap with the diene LUMO.

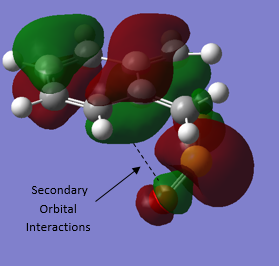

Thermochemistry (Endo and Exo Products)

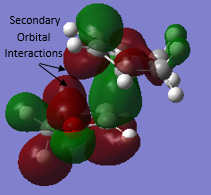

Thermochemistry data has been calculated at the B3LYP level (Table 6) to allow for the determination of the activation barriers and Gibbs Free energies associated with each reaction pathway. The activation barrier (activation energy) is the minumum amount of energy required for reactants to reach the TS before going to products via the minimum energy pathway. It can be seen from Table 6 that the activation barrier for the ENDO pathway to the ENDO TS is of lower energy and is thus more kinetically favourable. The ENDO product is the kinetic product due to an energetically favorable secondary orbital overlap between the oxygen lone pair p orbitals of the dioxole and the pi system of the cyclohexadiene. This overlap is only achieved through the ENDO TS and is shown in Figure 9.

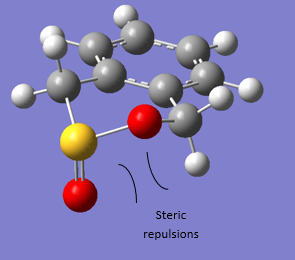

The reaction energy (Gibbs Free energy) is the energy difference between reactants and products, a more negative reaction energy is indicative of a more stable product in relation to the reactant. In this reaction the ENDO product has a lower reaction energy and is thus more thermodynamically favourable, as highlighted in Table 6. This also indicates that the formation of the ENDO product is more exothermic compare to the EXO product, which is a result of the EXO product containing an unfavourable steric clash between the bridge head hydrogens and dioxole. As a consequence the ENDO product is lower in energy than the EXO product by ~ 3.59 KJ/mol-1

| Product | Energy Barrier (KJ/mol-1) | Reaction Energy (KJ/mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| EXO | 167.67 | -63.75 |

| ENDO | 159.84 | -67.39 |

From the data calculated (Table 4) we can thus say that the ENDO product is both the kinetic and thermodynamic product of the reaction, due to both electronic effects and steric effects.

LOG Files

Log file B3LYP Optimisation cyclohexadiene

Log file B3LYP Optimisation 1,3-dioxole

Log file B3LYP Optimisation EXO TS

Log file B3LYP Optimisation ENDO TS

Log file B3LYP Optimisation EXO product

Log file B3LYP Optimisation ENDO product

Single point energy calculation reactants in EXO orientation (from IRC frame)

Single point energy calculation reactants in ENDO orientation (from IRC frame)

Nf710 (talk) 10:18, 17 April 2018 (BST) This was a very good section, you analysis of the single point energies of the MOs was particularly good. Your energies were correct and your have come to the correct conclusions. You also had some good diagrams and jmols to back up your discussion.

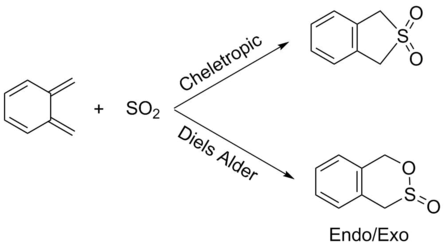

Reaction of O-Xylylene and SO2

Reaction Scheme

IRC Calculations

|

|

|

The possible reactions of the external diene of O-xylene and SO2 are shown in scheme 3. These reactions were explored at the PM6 level. IRC's for each of these reactions are shown in figures 10 to 12. Figures 10 and 11 show that bond formation is asynchronous when the EXO or ENDO Diels Alder pathways are followed (i.e C-O and C-S bonds do not form simultaneously). In the EXO/ENDO pathways bond formation occurs between the carbon and the oxygen first before bond formation between the carbon and sulfur. Figure 12 indicates that the cheletropic pathway proceeds with synchronous bond formation between the carbon and sulfur atom, where C-S bonds form simultaneously. In this reaction the o-xylylene is particularly reactive due to gaining aromaticity in the product, which drives the forward reaction. Alternatively, due to the high instability of o-xylene it typically undergoes an electrocyclic reaction to gain aromaticity, hindering its reactivity towards dienophiles.

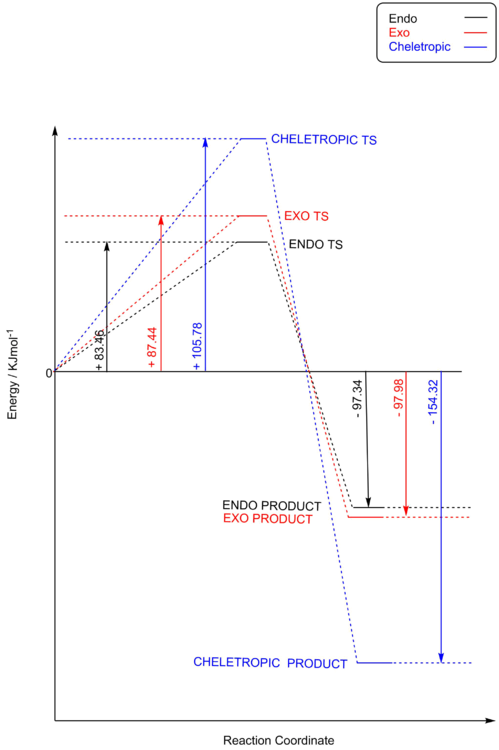

Thermochemistry

It can be seen from both Table 7 and figure 13, that the lowest energy barrier is associated with the ENDO reaction pathway and the most negative reaction energy is associated with the CHELETROPIC reaction pathway. These results indicate that the ENDO product is the kinetic product and the CHELETROPIC product is the thermodynamic product.

| Product | Energy Barrier (KJ/mol-1) | Reaction Energy (KJ/mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| EXO | 87.44 | -97.98 |

| ENDO | 83.46 | -97.34 |

| CHELETROPIC | 105.78 | -154.31 |

Again, due to energetically favourable secondary orbital overlap the ENDO TS is favoured resulting the the ENDO pathway having the lowest energy barrier. In this reaction the secondary orbital overlap can only be achieved in the ENDO TS as the non-bonding oxygen of the SO2 is in the correct orientation for its lone pair p orbital to interact with the pi system of the external diene of o-xylylene, as shown in figure 14.

The CHELETROPIC TS has the highest energy barrier owing to the sterically strained 5-membered ring formed during the TS (unlike the 6-membered rings formed in the ENDO or EXO TS which are less strained and lower energy), this can be visualized in in figure 12.

It can be clearly seen from figure 13 that the CHELETROPIC pathway is the most exothermic reaction leading to the most stable product, i.e. the thermodynamic product. This can be understood by analyzing the bond enthalpies of the bonds broken and bonds formed in the respective reactions. In the ENDO/EXO reactions one S=O bond must be broken whilst C-S, S-O and C-O bonds must form (in addition to the bond rearrangements leading to the aromaticity gain in the product). In the CHELETROPIC case two C-S bonds must form and the two S=O bonds are maintained (in addition to the bond rearrangements leading to the aromaticity gain in the product). In light of this, the bond energies involved in forming two C-S bonds and maintaining two S=O bonds (CHELETROPIC) exceeds the bond energies involved in breaking one S=O bond and forming the C-S,S-O and C-O bonds (ENDO/EXO).[9] With regards to the ENDO and EXO products, the energy difference is marginal, however, the EXO product is slightly more stable. This can be explained by steric effects, as shown in figure 15, where an axial repulsion between the pseudo axial S=O and adjacent axial hydrogen in the formed ring system of the ENDO product is energetically unfavourable. This repulsion is not present in the ENDO product where the S=O sits pseudo equatorial.

Alternative Diels Alder With Internal Diene

There is an internal diene in o-xylene which does not undergo Diels-Alder reactions with SO2. The reason for this was evaluated at the PM6 level using Gaussian, thermochemical data is given below in Table 8.

| Product | Energy Barrier (KJ/mol-1) | Reaction Energy (KJ/mol-1) |

|---|---|---|

| EXO | 121.51 | 22.40 |

| ENDO | 113.68 | 17.96 |

From Table 8 it can be clearly seen that the energy barriers for these alternative ENDO/EXO pathways exceed those of the aforementioned external diene ENDO/EXO and CHELETROPIC pathways. It should be noted that reaching the ENDO TS with the internal diene requires lower energy, again explained by stabilization brought about secondary orbital overlap between the non-bonding SO2 oxygen lone pair p orbital and the pi system of the internal diene of o-xylylene (akin to that in figure 14). In the alternative Diels-Alder reactions no aromaticity is gained (in addition to diene conjugation being lost) and so the products obtained are less stable than the products from the previously discussed pathways where aromatically is gained in all three cases. Thus, the reaction energies are positive indicating that both of these alternative ENDO/EXO pathways are endothermic reaction pathways. IRC's of each of the alternative ENDO/EXO Diels Alder pathways are given in figures 16-17.

|

|

LOG Files

Log file PM6 Optimisation O-Xylyene

Log file PM6 Optimisation EXO TS

Log file PM6 Optimisation ENDO TS

Log file PM6 Optimisation CHELETROPIC TS

Log file PM6 Optimisation EXO product

Log file PM6 Optimisation ENDO product

Log file PM6 Optimisation CHELETROPIC product

Log file PM6 Optimisation Alt. EXO TS

Log file PM6 Optimisation Alt. ENDO TS

Log file PM6 Optimisation Alt. EXO product

Log file PM6 Optimisation Alt. ENDO product

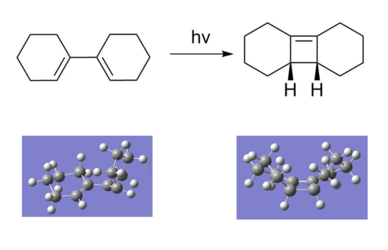

[1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene Photochemical 4π Electrocyclisation

Reaction Scheme

Möbius–Hückel Treatment

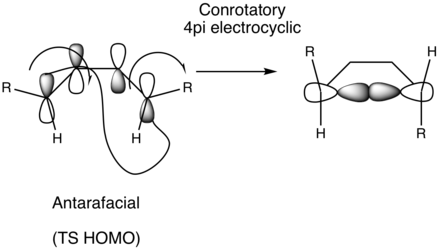

Under photochemical conditions, a 4pi reaction is predicted to proceed via a Hückel aromatic transition state with suprafacial bond formation and a (presumed) plane of symmetry. The electrocyclic reaction of [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene was analysed computationally using Gaussian at the PM6 level (ground state).

The TS HOMO for a photochemical butadiene electrocylic closing is governed by a Hückel topology for 4n electrons and Möbius topology for 4n+2 electrons. In this reaction there are 4n pi electrons. The TS for the reaction is shown below in figure 18 and indicates that the reaction proceeds via a Möbius topology, as indicated by the slight twist in the termini orbitals where the new C-C bond forms, suggesting that the product is formed under thermal conditions.

(All these calculations are occurring on the ground state. Visualisation of the IRC or transition vector from a frequency calculation would confirm that 4pi electrocyclic reactions occur with disrotation Tam10 (talk) 15:56, 4 April 2018 (BST))

| Figure 18. HOMO of TS (Möbius topology) for [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene electrocyclisation | Figure 19. Negative vibration of the TS for the [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene electrocyclisation, bonds move in a controtatory fashion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The negative vibration for the TS, figure 19, suggests that the reaction proceeds in a conrotatory manner and is thus antarafacial. Interestingly, the stereochemical outcome has the two hydrogens with the same stereochemistry (both axial) which opposes what is expected with typical conrotatory motion, illustrated in figure 20. In other words suprafacial specificity is observed. This is most likely due to the orientations of the hydrogens, where they do not point towards eachother in the S-Cis conformer of [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene (see scheme 4). It would be energetically unfavorable for the hydrogens to point towards eachother in the S-Cis conformer, this is reinforced by the lack of symmetry in the starting reactant. The IRC for this reaction supports this further and can be visualised in figure 21. Note that in the TS the plane of symmetry is not conserved.

|

LOG Files

Log file PM6 Optimisation [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene

Log file PM6 Optimisation electrocylisation product

Conclusion

In this work, four pericyclic reactions (cycloadditions and an electrocylisation) have been explored computationally at the PM6 and B3LYP/6-31G(d) level using GaussView to calculate geometries of the TS and products. Using the methods employed, reaction energetic's have also been probed to provide predictions for the outcome of each reaction and alternative reaction pathways. Calculations at the PM6 level have afforded sufficient structures within a short time frame owing to reduced computational cost associated with these calculations. PM6 has been successfully employed to determine how bond lengths (C-C and C=C) change in a butadiene-ethylene cycloaddition and the obtained results lie in parallel to literature. Optimisations at the B3LYP level allowed for the calculation of TSs with enhanced accuracy, specifically allowing for the quantitative determination of the electron demand of a cyclohexadiene and 1,3-dioxole cycloaddition reaction, in addition to the activation energy and reaction energy of the respective EXO and ENDO pathways. Methodology which involved drawing out products, guessing TSs and optimizing TSs (methdod 3) has worked particularly well on the cycloaddition of o-xylyene and SO2, affording reaction energies and energy barriers which match with theory regarding steric effects and electronic effects. In particular, the electronic effects of stabilizing secondary orbital interactions have been visualised through PM6 optimisations of the TS of the-oxylylene - SO2 cycloaddition on GaussView. An extension reaction involving the electrocylisation of [1,1']bicyclohexyl-1,1'-diene (4n pi system) has been explored at the PM6 level. Calculations have allowed for the exploration on the Möbius and Hückel topology of the TS, results indicate that the reaction can proceed via a Möbius TS (HOMO) in an antarafacial fashion.

This work demonstrates a simple approach in using time effective computations to predict outcomes of reactions prior to experiment, illustrating the sheer power of computational chemistry in organic chemistry.

References

<references>

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 H.S Rzepa, J. Chem. Educ., 2007, 84 (9), p 1535

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 D.J. Wales, Energy Landscapes: Applications to Clusters, Biomolecules and Glasses, CUP, Cambridge, 2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 T. H. Dunning Jr, J. Chem. Phys., 1970, 53, 2823-2833.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 J.J.W. McDouall, Computational quantum chemistry : molecular structure and properties in silico, 2013

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 B. Santra, Dissertation, Technische Universität Berlin, 2010

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 J. Clayden,N. Greeves,S. Warren and P. Wothers, Organic Chemistry , 2001

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 A. Bondi., 1964. van der Waals volumes and radii. The Journal of physical chemistry, 68(3), pp.441-451

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 P.W Atkins & J. De Paula, Atkins' physical chemistry 9th ed., Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Y.R Luo, Comprehensive handbook of chemical bond energies. CRC press, 2009